I was very, very, very sure that what we were doing was extremely important and was destined to be successful. So, that's the definition of an insane person or a zealot. And most entrepreneurs, I think you would find, have that sort of green wire laid in there just a little bit crosswise.

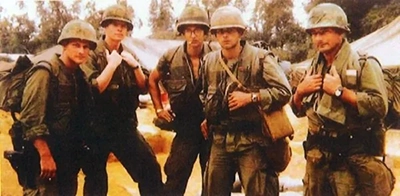

Frederick W. Smith was born in Memphis, Tennessee. The Smiths were a well-to-do family, but Frederick’s father died when he was only four, and the growing boy had to rely on his mother and uncles for guidance. While attending Yale University, Fred Smith wrote a paper on the need for reliable overnight delivery in a computerized information age. His professor found the premise improbable, and to the best of Smith’s recollection, he only received a grade of C for this effort, but the idea remained with him. After graduation, Smith enlisted in the Marine Corps and served two tours of duty in Vietnam. As the Yale-educated son of an affluent family, Lt. Smith had some adjustments to make to the realities of war, but he cherished the advice given him by a veteran Marine sergeant: “There’s only three things you gotta remember: shoot, move and communicate.”

While in the military, the young lieutenant observed military procurement and delivery procedures carefully, with an eye toward someday realizing his dream of a vast network dedicated to overnight commercial delivery. Smith got his chance when he left the service and started his express transport business in 1971. “I wanted to do something productive after blowing so many things up,” he told an interviewer.

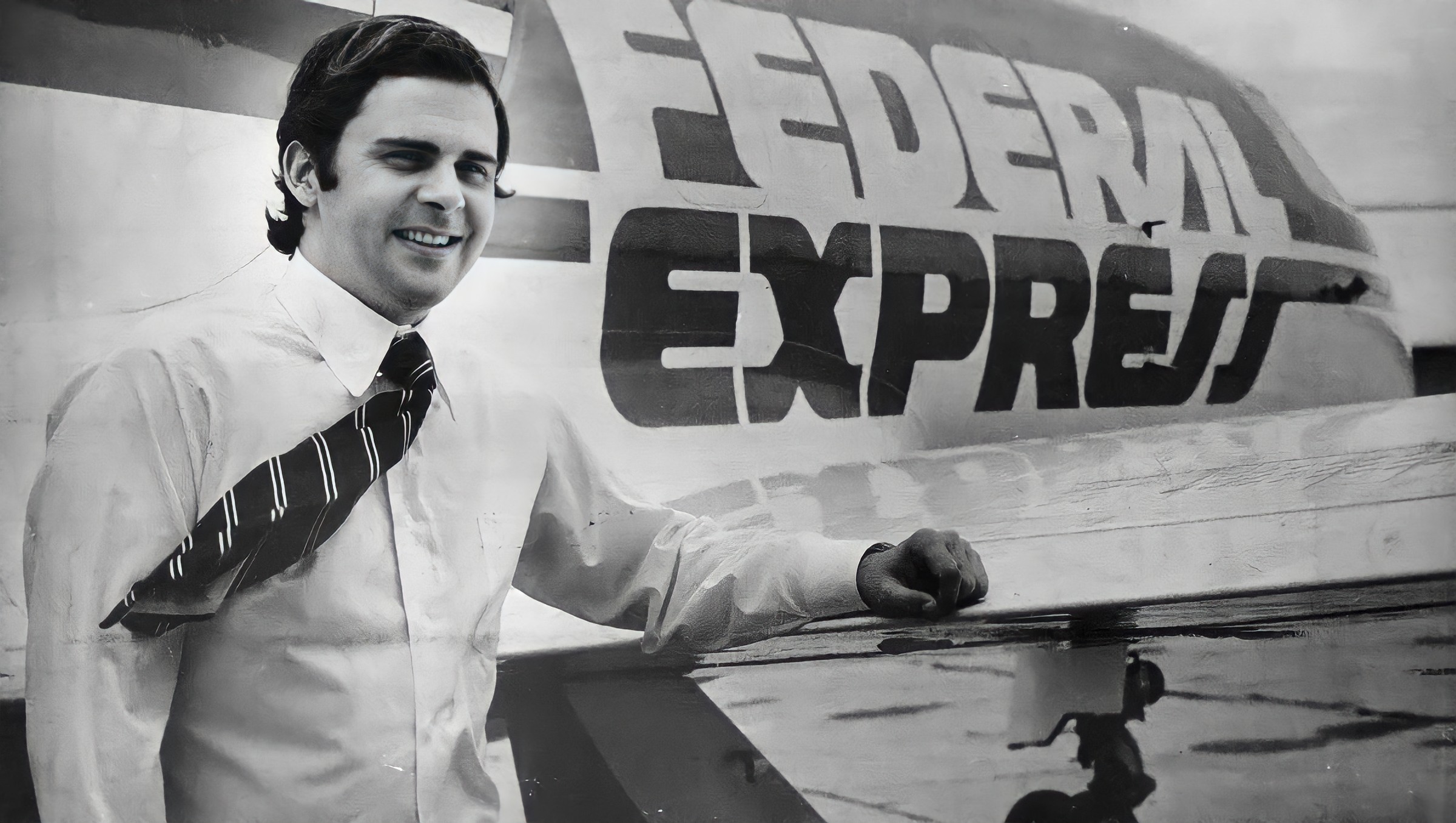

The young entrepreneur raised $80 million to launch Federal Express, informally known as FedEx. The delivery service began modestly with small packages and documents. On the first night of operations, a fleet of 14 jets took off with 186 packages. In the first two years, the venture lost $27 million. In a short time, the company was on the verge of bankruptcy. It appeared that Smith had lost all of his investors’ money, including the capital of his own brothers and sisters. But Smith succeeded in renegotiating his bank loans and was able to keep the company afloat.

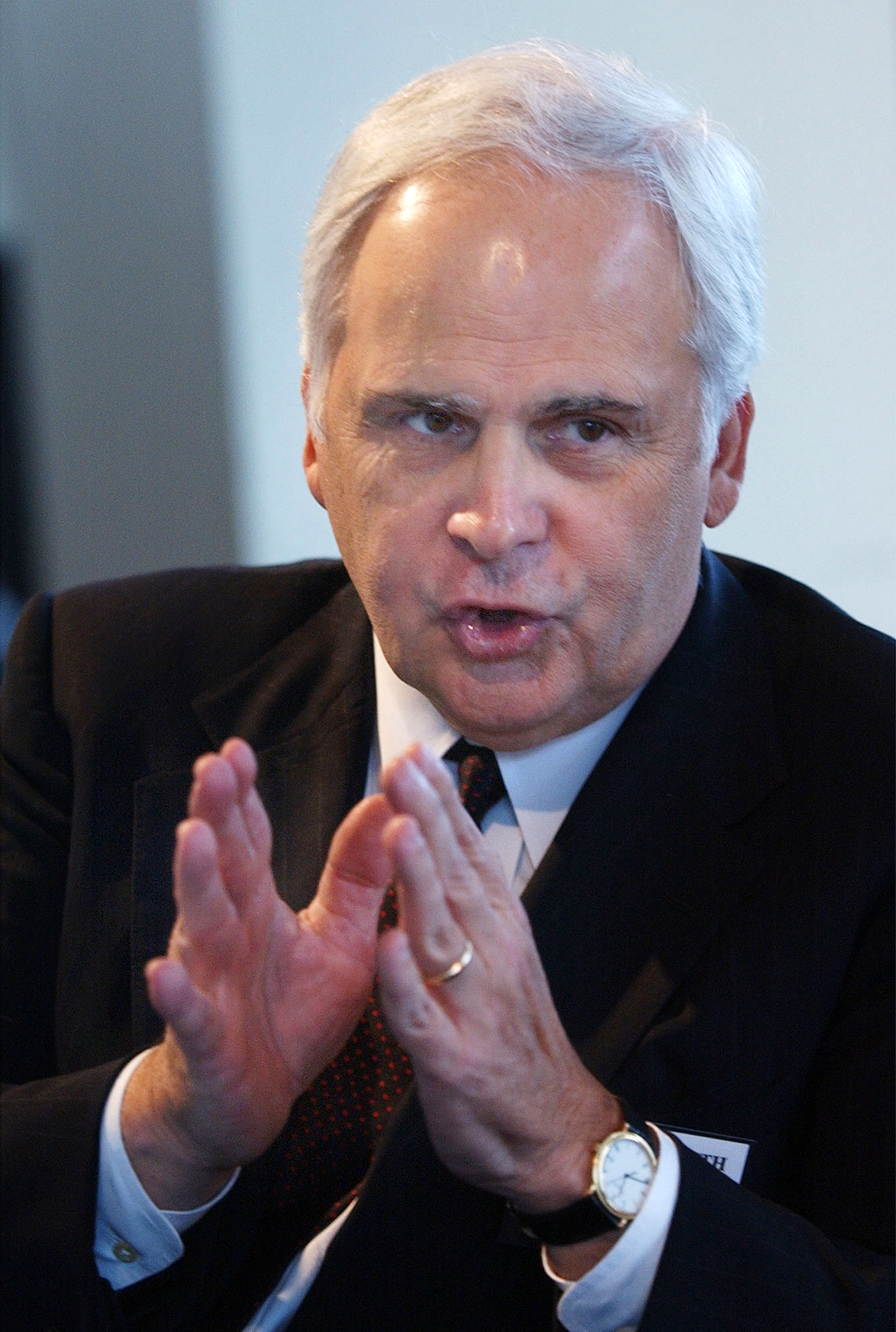

Unlike many entrepreneurs, Fred Smith is also a hands-on manager, who directs every facet of corporate strategy. He determined at the outset that FedEx was in the information business — that knowledge about origin, present whereabouts, destination, estimated time of arrival, price and shipment cost of his cargo was as important as its prompt delivery.

Another principle Smith applied at FedEx was to make sure every employee felt they could share in the success of the company. FedEx managers are carefully trained to ensure respect for all employees, and their performance is monitored. Managers are evaluated annually by both bosses and workers to ensure good relations between all levels of the company. Smith believes that fair treatment instills company loyalty, and that company loyalty always pays off.

Smith’s professor at Yale may not have seen the need for overnight delivery, but today’s business world depends on businesses like FedEx shipping all manner of goods around the globe quickly and reliably. Smith’s fleet of MD11s and A300s circle the globe carrying all manner of goods: Maine lobsters, Japanese cherries, Hawaiian flowers, medicines, heart monitors, contact lenses, surgical scalpels, tennis shoes, circuit boards, fresh blood, tractor parts, auto bumpers, European fragrances, Swiss watch parts. As Smith says: “We are the clipper ships of the computer age.”

In 1997, Smith acquired the $2.7 billion Caliber System, whose trucking subsidiary RPS ranked second in ground shipments, exceeded only by UPS, the United Parcel Service. The RPS fleet of 13,500 trucks increased FedEx’s profit margin, because ground fleets are cheaper to operate than airplanes. It also gave FedEx the extra muscle it needed to step into the breach when FedEx competitor UPS was immobilized by a strike later that year.

Fred Smith’s effort to instill company loyalty bore fruit. During the UPS strike, when FedEx was swamped with 800,000 extra packages a day, thousands of employees, many of whom had already worked a full day, voluntarily poured into the hubs a little before midnight to sort the mountain of extra packages. Smith publicly thanked them in 11 full-page newspaper ads; he also ordered special bonuses.

When the strike was over and the smoke cleared, FedEx had pulled roughly two percentage points of market share away from UPS, increasing its share of the express transportation market to more than 43 percent. The stock market responded to FedEx’s gains. Over the course of the year, the company’s share price rose by nearly 70 percent. While UPS has faced additional labor unrest among its pilots, FedEx pilots are among the best-compensated and most contented in the industry.

Fred Smith has never allowed FedEx to rest on its laurels. Continuous improvement is one of his fundamental management principles. In the 1990s, the company installed computer terminals in the offices of over 100,000 customers and gave proprietary software to more than half a million more, enabling shippers to label their own packages. Today, most FedEx customers print their own labels directly from the FedEx website. FedEx receives electronic notification to pick up the cargo, then ships and delivers. Competitors in the express delivery business are still rushing to catch up with FedEx’s technological advances.

In 2001, FedEx made an unprecedented deal with the United States Post Office, contracting to transport large mail shipments for the Post Office, while installing FedEx drop boxes in U.S. Post Offices. Three years later, FedEx also took on international express shipments for the Post Office. That same year, 2004, FedEx purchased the document services company Kinko’s, eventually renaming the business FedEx Office. At over 1,800 locations across the United States, customers can print, copy and bind their documents and dispatch them for overnight shipping from one convenient location. In April 2015, FedEx acquired their rival firm TNT Express for 4.8 billion as the company expanded their operations throughout Europe.

In March 2022, Smith announced he is stepping down as chief executive of FedEx, the company he started more than 50 years ago. At 77 years old, he is handing the CEO role to President and Chief Operating Officer Raj Subramaniam. Smith, who is also chairman of the FedEx board, will transition to executive chairman on June 1, when the leadership change will take place.

Today, FedEx Corporation is the world’s leading express transportation provider. More than 600,000 FedEx team members worldwide field a fleet of 680 aircraft and more than 200,000 other motorized vehicles, delivering over 18 million packages every business day, to more than 220 countries and territories. In 2021, FedEx’s annual revenue exceeded $87 billion.

Fred Smith amassed a personal fortune of $6 billion by enabling the world of business to deliver its goods quickly, anywhere in the world. Businesses seeking to reduce the costs of maintaining large inventory are increasingly adopting “just in time” delivery practices, increasing the demand for express services like FedEx. The rise of Internet commerce and the growth of the global economy also contributed to the company’s growth. FedEx capitalized on both of these trends, with proprietary software for Internet catalogue service, and the completion of facilities in the Philippines, Taiwan, France and China. Around the globe, communications and transport continue to develop along the lines Fred Smith predicted in his term paper half a century ago.

“We’d run out of money, and we didn’t have all of the regulatory requirements that we needed. My half-sisters were up in arms because it looked like we were going to lose some money. Everything was going wrong, except the fundamentals of the business were proving every single day that the idea was right.”

In 1974, it looked as though Fred Smith’s dream of a worldwide overnight delivery system was about to go up in flames. His family’s capital was spent, the bank loans were due and the demand for a service of this kind was still unproved. But Smith hung on, and subsequent developments in the world economy proved him right.

Today, few in the business world could imagine getting along without an overnight delivery system like Federal Express. FedEx drop boxes and FedEx trucks are a familiar part of the American landscape, and FedEx planes circle the globe delivering everything from chocolates to airplane parts.

Fred Smith, Chairman and CEO of Federal Express Corporation, is known as the “father of the overnight delivery business,” and the Marine Corps veteran who teetered on the verge of bankruptcy is one of American business’s greatest success stories.

Where and when did you get the idea for Federal Express?

Frederick Smith: The original idea came in two parts. The first part was when…

I was a student at Yale and wrote a paper about the computerized society that was on the horizon. It was pretty clear then, with IBM installing the big computers around, that the world was going to change. And the paper was about how this was going to change a lot of things, and in particular it was going to change the way things had to be distributed and moved to support those automated devices. Then I sort of let that lie. I didn’t get a particularly good grade on it, as I recall.

I don’t think it was prescient, or brilliant in any respect. When I graduated from Yale in 1966, I went into the service, like a great percentage of my classmates at that time. The Vietnam War had begun in earnest, and I spent four and a half years in the Marine Corps. That’s when I sort of crystallized the idea for FedEx on the supply side, how to solve the problem that had been identified in that paper.

In the military there’s a tremendous amount of waste. The supplies were sort of pushed forward, like you push food onto a table. And invariably, all of the supplies were in the wrong place for where they were needed. Observing that and trying to think about ways to have a different type of a distribution system is what crystallized the idea.

The solution was, in my mind, to have an integrated air and ground system, which had never been done. And to operate not on a linear basis, where you try to take things from one point to another, but operate in a systemic manner. Sort of the way a bank clearing house does, you know? They have a bank clearing house in the middle of all the banks and everybody sends someone down there and they swap everything around. Well, that had been done in transportation before: the Indian post office, the French post office. American Airlines had tried a system like that shortly after World War II. But the demand side and supply side had really not met at an appropriate level of maturation.

By the early ’70s, when I’d gotten out of the service, it was very clear that this new society was coming in earnest. And so, at that point I said, “What the hell, let’s try to put it together.” And that’s how FedEx came to be. And then from that point forward, the requirements for this type of system were so profound and so big, really for the next 25 years to this date we’ve simply been running just to keep up with the requirements. And that’s what led to the hundreds of planes and the thousands of trucks. I wish it was something that I could say I was so smart. It was just like Pogo the Possum said, “If you want to be a great leader, find a big parade and run in front of it.” And that’s what we’ve been doing for the last quarter century.

There are a lot of people with ideas, and brains, and potential who don’t achieve whatever goals they might have. How do you account for your success? For your ability to do what you’ve done?

Frederick Smith: First and foremost, the idea was a profound idea, as has been shown. Today we have 170,000 employees and $16 billion. As I said, the requirement for this type of a system was so great and was increasing at the time. I just had the good luck to have an idea that was on the tide of history.

I’m sure many other people who’ve been much more successful would say the same thing. Bill Gates was given the opportunity to make the operating system for IBM and then there was a huge explosion of demand for PCs. I wish it were not the case, but an awful lot of success is being in the right place at the right time. That was a very big part of it.

Naïveté was also a big part. I didn’t know that I couldn’t do this.

In retrospect it was ridiculous to try to put this system together, which required so much up front money, and required changing a lot of government regulations, but I didn’t know that at the time. And I think probably my experience in the service, where — the currency of exchange in FedEx was just money, it wasn’t people’s arms and legs, or lives. So my perspective on it was perhaps a bit more — I don’t know how you’d say it. I was willing to take a chance, because losing wasn’t the worst thing in the world that could happen to you. I had seen that very clearly. So luck, naïveté, willingness to roll the dice to do something productive, were all individual parts of the puzzle.

You had a certain vision. The post office didn’t come up with this idea.

Frederick Smith: I was very convinced that the idea was the central feature of the new economy. That without a system like this, it simply wasn’t going to be able to work. So I was, in every sense of the word, a zealot. I mean, I felt very strongly that this needed to be done, that it was something that would be extremely useful to people and that it would make the economy and the society and the system work much better than it would work absent that. So many things have evolved out of that system. Dell Computer relies on the types of systems that we pioneered. High-tech and high value-added businesses are by far the preponderance of economic activity in this country and increasingly around the world, and these types of business are facilitated by systems like FedEx, or — I hate to say it — our able competitors.

There are always detours. What kind of adversities have you had to overcome?

Frederick Smith: I’ve had all kinds of adversity, but I think you have to put those things in perspective. I have to go back to my experience in the Marine Corps. My life has been a walk in the park compared to the adversity that a lot of people have seen. I’ve enjoyed every bit of putting the company together. Even the bad parts I learned from. I’ve enjoyed it immensely, and I enjoy what I’m doing today. I enjoy running the company.

Going to war does give one some perspective.

Frederick Smith: It really does. I can’t emphasize that enough. That puts a different perspective on things forever.

From what I’ve read, 24 years ago this month you were at a low point in trying to make Federal Express happen. Can you tell us something about that?

Frederick Smith: We’d run out of money and we didn’t have all of the regulatory requirements that we needed. My half-sisters were up in arms because it looked like we were going to lose some money. I mean, everything was going wrong, except the fundamentals of the business were proving every single day that the idea was right. I mean, every single day the traffic was going up, and so eventually everything came right and worked out fine.

The motivation I had in those days was that I didn’t want to let down the people who had signed on with me. It goes straight back to that Marine Corps experience. I wasn’t afraid to lose my money. I knew I was right, I knew I had put this thing together properly and that it was going to be all right. That was what stood me in good stead.

You never lost confidence.

Frederick Smith: The reason I never lost confidence is because I never believed that the consequences of losing were as bad as some other people might have thought, you know? “Oh my goodness, I’ve lost my money!” or what have you. I mean, I just wasn’t motivated along those lines. And I was very, very, very sure that what we were doing was extremely important and was destined to be successful. So that’s the definition I think of an insane person, or a zealot. And most entrepreneurs, I think you would find, have that sort of green wire laid in there just a little bit cross-wise. And they begin to get focused on something, and they believe in the idea or themselves far beyond what they probably should.