Your plan was rather daring, and it certainly worked. Is it true that there’s a connection to the World War II battle of El Alamein, in which Montgomery vanquished Rommel?

Norman Schwarzkopf: No. The deception tactics of Desert Storm compare favorably I think. The Battle of El Alamein was the turning point in North Africa. It’s considered one of the three decisive battles of World War II. The British used deception tactics to make the Germans think that they were going to attack where they weren’t. That’s the parallel between Desert Storm and the World War II battle. I can name any number of campaigns where the major portion of the enemy was fixed by one force here, while another force went around and hit them. That’s sort of a classic maneuver, if you can get away with it, if you’ve got the forces.

Did you have any doubts that this strategy was the right way to go?

Norman Schwarzkopf: My job is to have doubts. My job is to think of everything that could possibly go wrong, and then try and fix it. Let’s face it, I knew that I was going to be ordering thousands and thousands and thousands of men and women into battle, and if I didn’t have it right, I could be responsible for the deaths of thousands and thousands of people. That’s sort of a heavy burden to carry, so you don’t carry that burden lightly. You don’t carry that and say, “Oh ho-hum, so what.” No. To my mind, if you have any sort of a conscience at all, you have doubts, but you work your way through those doubts. You work it in such a way that you’re quite sure that you’ve done everything you can possibly do, so that the outcome is a favorable one.

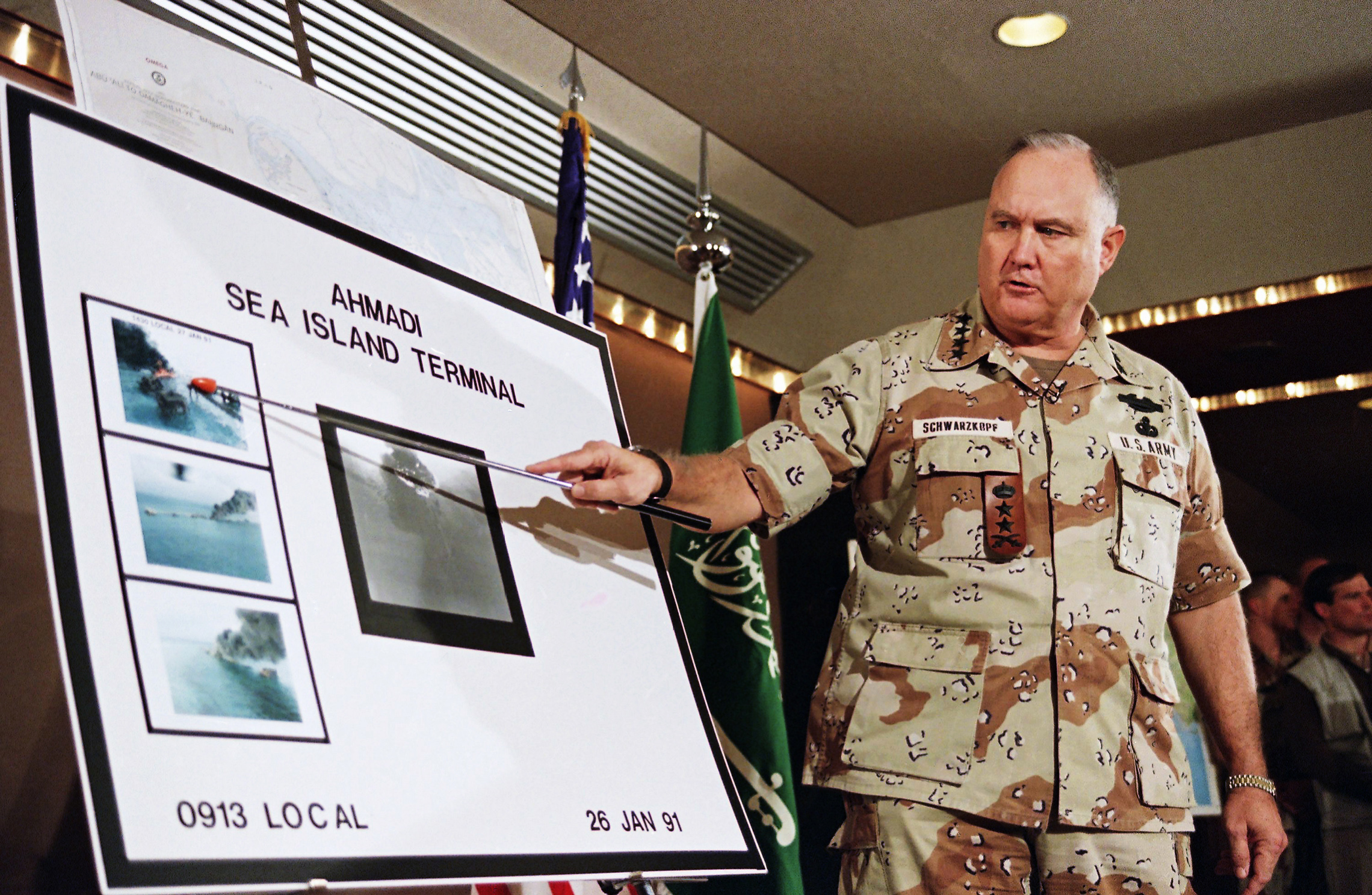

What was your general strategy for getting the Iraqis out of Kuwait?

Norman Schwarzkopf: It was very simple. I had studied the Iraqis in great detail in their battles against the Iranians. I knew what their strengths and weaknesses were. I also knew the forces I had under my command, and I knew what their strengths and weaknesses were. I adopted a campaign plan that capitalized on using our strengths against their weaknesses – and avoided their strengths, and avoided our weaknesses. That’s a pretty good strategy for any kind of business you’re in. Let me give you a good example. I knew that our Air Force was much better than theirs. So, I devised a strategy that relied heavily on us conducting an aggressive air campaign, because I knew we could take their air out. I knew that they routinely fought during the daytime, and re-supplied at night. But we fight better at night than we do in the daytime. So I knew I could take the night away from the enemy, and totally disrupt the way they normally re-supply themselves, and put them in a position where eventually they were going to run out of supplies, and they were going to run out of ammunition and everything else because we just took the night away from them. That’s what it was. It’s an analysis of your enemy to learn their strengths and weaknesses. You know your strengths and weaknesses, and then you just use your strengths against their weaknesses.

It pays to be prepared.

Norman Schwarzkopf: You don’t rush into these things without thinking. But I think that’s the strategy for any kind of business you’re in. If you’re competing against someone, that’s what you should be doing.

Still, didn’t it surprise you, the lack of effective Iraqi response? It surprised us.

Norman Schwarzkopf: No. Let me tell you why. We put together a campaign plan specifically to make sure that by the time we launched a ground campaign the Iraqis could not respond. That’s what happened. The campaign plan was aimed at absolutely destroying, insofar as possible, the Iraqis’ ability to wage war. Today, a lot of people are saying the Iraqis really weren’t there. That’s ridiculous. The Iraqis were there on the 17th of January when we started the air campaign. Whether the Iraqis were there on the 24th of February, when we launched the ground campaign, or not, is irrelevant. Probably a lot of them weren’t. We knew there had been mass desertions at that time. We knew that their units were under strength. We knew that we had inflicted great casualties on their tanks and their artillery pieces. Why? Because that’s what we were going after. We were deliberately trying to eliminate those things that we knew would hurt us on the battlefield. One of my criteria was to reduce the strength of the front line forces that we had originally run into to below 50 percent. We generally classify a unit that’s below 70 percent as combat-ineffective. Below 50 percent it’s totally ineffective. The campaign plan turned out exactly like we had planned it. It was a campaign plan that had been very carefully constructed to make sure that when we finally had to send our ground forces against his ground forces, who outnumbered us originally, that we would prevail.

Did you feel this was the right time for us to use force?

Norman Schwarzkopf: Sure. We had tried over, and over, and over again to bring about a peaceful solution. The Secretary General of the United Nations went to Baghdad because that’s the only place the peaceful solution was going to come from. Everybody else wanted a peaceful solution. Countless diplomats from east, west, north, south, from the then Communist bloc, all went to Baghdad, because that’s where the peaceful solution had to come from. Secretary Baker met with Tariq Aziz in Geneva, where he came out and gave that pessimistic report and said, “I’ll let the Iraqis speak for themselves.” And then Tariq Aziz came out and spoke for 45 minutes. Didn’t even mention the word “Kuwait.” The country had been blotted off the map as far as the Iraqis were concerned, and that was irrevocable. Nothing else was going to change after that.

When you looked at other things, like the effects of the weather, some people say we should have let the sanctions run a little bit longer. That’s very nice to say if you’re sitting in the comfort of your living room in the United States of America. But if you were somebody who was in Kuwait and you were seeing your children tortured, and your wives raped, and the terrible things that were going on to the people in Kuwait, was it okay to wait for them? These things are very, very relative to who you are and where you are.

Consider the troops that were sitting out in the desert sand. It may have been fine for everybody else to say we ought to wait and let the sanctions work. But did we really want to go through another summer with our troops in the absolutely oppressive heat of the desert, just sitting there suffering? Was that all right? While their morale was going, down, down, down? So when we put it all together, there was no question. That was a time to go and get it over with. We had done everything else we possibly could to end it peacefully.

What effect did advances in technology have on the war? How did you see that?

Norman Schwarzkopf: We were able to take the night away from the enemy, and that’s probably one of the major ones. But you’ve got to remember, our armed forces have been training for years to fight outnumbered and win. We thought we were going to be fighting against the Soviet Union, a military that had many, many more tanks than we did, many, many more armored personnel carriers, many, many more aircraft. So you have a military out there that was very well trained to do the job that needed to be done. It’s a combination of the technology, yes, but also the training of the military — some very, very good military.

What’s it like working with Colin Powell?

Norman Schwarzkopf: As a unified commander, I really answered directly to the Secretary of the Defense. In this case, I really worked directly for the President. Colin Powell was the person that passed to me the directives of the President of the United States. But as a unified commander you really have tremendous autonomy. You’re almost working for yourself. People tell you what to do, they don’t tell you how to do it, and then you go off and do it. But Colin and I were good friends. We talked to each other on the phone every single day. I kept him informed of everything that I planned to do. In most cases when an order was to be given, he’d call me up and say, “What do you want to do with it?” And I’d say, “This is what I want to do,” and that’s the order that would come back down again. We had a very good relationship, as I say, talked to each other every single day. What was really terrific about Colin is he probably had more access to the White House than any general officer since George Marshall in World War II. Marshall was really the person that Roosevelt looked to for all of his military advice. I think the President did the same thing with Colin, and you could get decisions very quickly because Colin had this direct access to the White House, and that helped us tremendously in our work.

The President pretty much let you do what you wanted to?

Norman Schwarzkopf: Yeah, I would say, he let you do what you wanted, so long as he knew what you were doing was right. I don’t think I could have done the wrong thing. If I had proposed some things that were stupid, or things that would lead to thousands and thousands of casualties, or something that was immoral, or unethical, of course, I wouldn’t be able to do it.

The President was very presidential. The President did exactly what a president does. He told you what to do, he gave us our orders, and then he stayed informed all along the way, in great detail, as to what it was we were doing. But he did not interfere and decide that he was going to play “General.” That’s very important.

Did that happen to some extent with the Vietnam War?

Norman Schwarzkopf: Yeah. During the Vietnam War, targets that were going to be bombed by the Air Force in North Vietnam were being selected by politicians back in Washington. That’s crazy. If you’re going to bomb a target, it should be a target that fits in with the overall campaign plan. Not just something that’s arbitrarily selected back in Washington.

There was some controversy about the way the information coming out of Riyadh was handled. There was tremendous control of the press.

Norman Schwarzkopf: That’s a word I violently disagree with. Nobody controlled the press over there at all. That’s an argument that is argued in all the wrong arenas. It is not a problem of the military versus the media. Don’t forget, the people in your military take an oath to support and defend the Constitution of the United States. That’s who we take our oath to. Most of the people I know of in the military are constitutionalists from the word go, and that’s all the Constitution, to include the First Amendment. You have a management problem. It’s a management problem that is growing by leaps and bounds, both numerically and technologically. Let me give you an example. The average number of reporters you had in Vietnam at any given time was 50. During the Tet Offensive, the most important battle probably fought during Vietnam, you had 80 reporters, in country. I can assure you all of them were no out with the troops because those of us who were in cities like Saigon saw plenty of them back there. In the Gulf you had 2,060. Secondly, in Vietnam when somebody saw a battle it was generally reported and it would end up on television perhaps 36 hours later. In the Gulf, people could report things instantaneously out over international airwaves via satellite. That was being piped directly into the enemy headquarters. So you had people who were reporting things that aided the enemy, that helped them, that helped them. There had to be some guidelines put out that said, look, these are things you don’t report. But, despite that, these guidelines were violated, not intentionally. They were violated by reporters who were looking to get a scoop. They wanted to get their story in first. The dilemma with the press in any future wars that are going to be fought is, how do you control these large numbers of the press that you’re going to have over there, who have instant access to the airwaves and your enemy is going to be monitoring those airwaves? How do you make sure that the press does not provide information that somehow can come back and kill one of the people that you’re responsible for? That’s the dilemma.

And it really comes down to that.

Norman Schwarzkopf: Of course it does. Nobody did anything in the Gulf because they didn’t like the press. Nobody did anything in the Gulf because they were trying to control the news stories. Our only concern, and the only reason why any restrictions were placed at all, was to make absolutely sure that, number one, you didn’t have 2,060 people running around inside your unit when you were preparing a military operation that you were trying to keep a secret. Number two, making sure that information didn’t go to our enemy. We knew Saddam Hussein watched television in his C.P. We knew that before the war ever started.

A New York Times reporter said that during the Vietnam War he spoke to his editor three times in three-and-a-half years, and in the Gulf War he spoke to him every few hours.

Norman Schwarzkopf: This war was the most extensively covered war in the history of warfare. There was access. That’s why I bristle at the word “control.” It sounds like there was some preconceived plot somehow against the media. We were just using our common sense, and our objective primarily was to make absolutely sure that the enemy didn’t get his hands on information that would aid and abet him, and eventually cost the lives of our forces. That’s all it was.

What particular moments in the Gulf War stand out for you?

Norman Schwarzkopf: This is probably the one that I’ll remember more than anything else. On the second day of the ground war when one of my corps commanders called me up, Gary Luck, to give me a report. And I said, “How are you doing?” And he said, “Sir, we accomplished all of our objectives yesterday.” This was about ten o’clock in the morning. “We’ve already accomplished all of our objectives today. We’re way beyond what we should have accomplished and we have captured over 1,300 of the enemy.” Then he kind of stopped, and I said, “Okay, Gary, now give me the bad news,” meaning the casualty count. And he said, “We have one wounded in action.”

Another moment I can remember is when we sent that initial wave of aircraft into Iraq. We expected much higher casualties. My Air Force Commander, Chuck Corner, kept calling me back saying, “Sir, they’ve all come back. They’re all coming back.” The recognition that you weren’t taking these casualties that you expected, those are the two moments I’ll probably remember more than any others.

Your father, who was also named Norman Schwarzkopf, was also an army officer. Could you tell us a little about him?

Norman Schwarzkopf: My father graduated from West Point in 1917. Became a captain in World War I. When the war was over, went back to El Paso, Texas. He was in the cavalry, guarding the border between the United States and Mexico. His father became a cripple in a wheelchair from arthritis deformans. And in those days, a captain in the Army didn’t make any money at all, and my dad was an only child, so he became the sole support of his parents. So he had to leave the military. He went back to New Jersey, and it just happened to be at a time when New Jersey had decided that they were going to form a State Police, and they were looking for the first superintendent who would organize and lead the New Jersey State Police. I won’t go into all the details, but it became a big political struggle. In those days, Army officers didn’t vote. The commander in chief was the commander in chief, and therefore it wasn’t right to vote for a political party. So Army officers didn’t vote at all. When my dad came back and applied for the job, they said, “What are your credentials?” “I’m a West Point graduate. I’ve had this experience in the military, and I’m a good organizer…” and that sort of thing. And they said, “What are your politics?” And he said, “I don’t have any. I’ve never voted in an election in my life.” Long story short: he became, at a very young age — I think he was 27 or 26 at the time — he organized and formed the first New Jersey State Police, and was their first superintendent and remained in that job for 15 years. About this time, he got fired, because my dad was very much involved in the Lindbergh kidnapping case, which was a very controversial case, and has been ever since then. Also, a political governor came in that he had been an enemy of for quite some time, and this governor did not renew my dad’s charter. So, after 15 years of leading the State Police, they said, “Thank you very much, we no longer need your services.” About that time things were heating up in Europe, and my dad had been active in the National Guard. So when the National Guard mobilized for World War II, my dad was mobilized with them. So he returned to the Army on full-time duty, and to make a long story short, he finally retired from the Army in 1957 as a major general. So, he had two careers. He had this career as a policeman, and this career in the military too.

I gather he was quite an influence on you.

Norman Schwarzkopf: Oh, he was. My dad was a man of great honor. He was a charismatic leader. He was one of these people that could tell a story, and just had you hanging on the edge of your chair. He would always get a great audience around him, because he was so good at weaving a tale. And I loved him dearly. And I think the fact that I didn’t have him at home for four years as a young man made me almost worship this person who was not there, who I so desperately wanted to be there as my father. So that when I was reunited with him, I really almost worshipped the ground he walked on.

Your father was stationed in Iran for part of the war. You lived there too, didn’t you? That was kind of unusual.

Norman Schwarzkopf: I think both of my parents decided it was time the family be reunited. So, we all went to Iran to be reunited as a family. But then the school system in Iran was terrible. One of my sisters was a senior in junior high school, and the other was a sophomore, and they didn’t have a decent school system in Teheran.

After one year of living in Teheran, my parents came to the very wise conclusion that our education was suffering. So, we all went to school in Switzerland for a year. Then my dad was reassigned to Germany. I went to Germany, and went to Frankfurt High School for a year, then Heidelberg for a year, and ended up in Rome. So, these wonderful, formative teenage years, I spent the whole time abroad, in one country after another.

Picked up some languages, too?

Norman Schwarzkopf: Yeah, I did. When I arrived in Switzerland I had only had one year of French, and hadn’t done very well. They put me in a room where my roommate was French, and didn’t want to speak English; sat me at a table with nine other people that spoke nothing but French. If you wanted to eat, you’d better learn how to say, “Please pass the bread,” in French.

That’s a wonderful way to learn a language, when you’re young, and your mind is so flexible. I was absolutely fluent in French within six months.

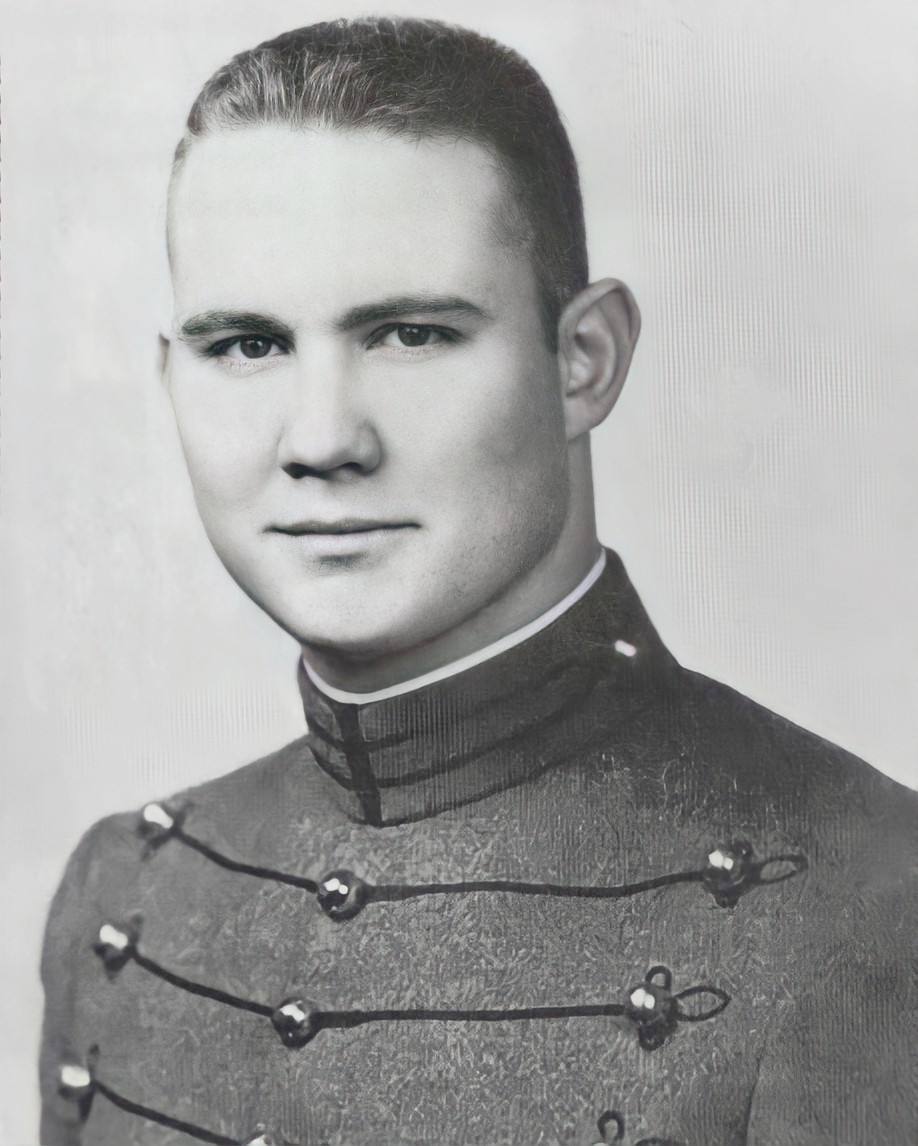

I saw a photo of you in a yearbook. I think you were a cadet of about ten, with a very serious expression. And the legend has it that you said, “I want this serious expression, because I’m going to be a general someday.”

Norman Schwarzkopf: I don’t think I quite said it that way. I think that’s part of a myth that has built up. But I think I said, “Men in uniform are supposed to look serious…” or something like that.

Back to the schooling, in general, were you a top student?

Norman Schwarzkopf: When I was a younger student, I was forever getting these comments on the report card that said, “He is not working to his potential. He can do much better than what he is doing.” I went overseas, and overseas I was more interested in learning by seeing, and feeling, and hearing, and experiencing, and that sort of thing. And amazingly enough, I came back to the United States and was a straight A student from there on out. Something clicked somewhere along the way, and I graduated valedictorian of my class in high school, and I was top 10% of my class at West Point, without very much work. And got a Master’s Degree in Guided Missile Engineering from USC. Something turned on. I was never a bookworm; I was always interested more in being more well rounded, rather than being perhaps viewed as perhaps an egghead.

You were also involved in sports, were you not?

Norman Schwarzkopf: I played football, was on the track team, ended up messing around with wrestling, and played soccer. In Switzerland I was on the Junior Championship Team of Western Switzerland as a fullback. I played a lot of tennis as a young man.

But I wasn’t all-American caliber, at the time. It’s only when I became a general that people looked back and said, obviously, he was an all-American football player. But it wasn’t true. I was a very good high school athlete, but I was certainly not a very good college athlete.

What particular event or experience inspired you most growing up?

Norman Schwarzkopf: I don’t think I can pick a single experience. Of course, World War II had a tremendous impact on me. It’s something that not many people younger than me in the country today remember, but at that time the entire world was at war. It was a battle between good and evil. And it was a world war, it wasn’t a geographically limited war. So the whole country was involved.

There were fund-raisers, and there was rationing, and there were alerts, and you had to go through air raid drills, and this sort of thing. That certainly had a major impact upon my life as a young man, and particularly as a young boy when my dad was gone. To me, this all translated into my father being in some kind of danger.

There’s no question about the fact that the teenage years that I spent abroad had a tremendous impact upon my entire life, from that time forth. I mean, I got to know people of so many different nationalities, of so many different cultures, of so many different ethnic backgrounds. In meeting all of these people of so many different make-ups, it was a wonderful education for me. It taught me that there’s more than one way to look at a problem, and they all may be right, you see. So, it gave me a certain tolerance. Maybe tolerance isn’t the right word, because tolerance implies that there’s intolerance before. It’s not that, but it just gave me an appreciation for people. Judge them as you find them. Never prejudge anybody based upon any of those things that sometimes people are prejudged. That’s lived with me for the rest of my life. It gave me the ability to be flexible, to get along with people of all different nationalities.

That came in handy recently.

Norman Schwarzkopf: You betcha.

Was there, by any chance, a book, or a couple of books that meant a lot to you as a kid?

Norman Schwarzkopf: Oh, no, I read a lot. I read the whole Lassie Series. Jack London was one of my favorite people. I was fascinated by early mythology, and I read the Iliad and the Odyssey several different times. When I was a young man I read Das Kapital by Karl Marx, only because communism was this thing looming on the horizon, so I wanted to learn something about it.

I wouldn’t say any one particular book. I enjoyed reading. It was fun to read. Remember, we didn’t have television in those days. So, you either listened to the radio, or you picked up a good book, that was the way you learned.

What about in your school life? Was there a particular teacher that meant a lot to you?

Norman Schwarzkopf: People have asked me that over and over again. There was no one teacher. I always wish I could say something like that, but I can’t. I can think of several that helped me along the way. At just the right time they were there to nudge me in the right direction, to get me perhaps to do something I hadn’t considered doing, and it opened up new horizons. But there wasn’t just one particular person at all.

If you want to look for one particular person, it was my mom and dad. They were the teachers that taught me a great deal.

What draws you to this career? This is a glamorous one of late for you, but years of life-threatening work, tremendous responsibility that most of us can hardly imagine, and time away from your family. What are the things that make this such a passion for you?

Norman Schwarzkopf: The challenge, and the sense of service. Perhaps the sense of service, more than the challenge. You know that you’re serving something beyond yourself. You derive the reward from the fact that you are dedicating your life to serving your country.

The troops. The troops sometimes make it all worthwhile. I mean, they really do, it’s great to be with them. Someone once said, when it quits getting fun, you ought to get out. And I say, whoever said that has never been a leader of troops. Because I can think of a lot of times when it wasn’t fun at all, but it’s a series of emotional peaks and valleys. And what you hope is that you have more peaks than you do valleys, and you do. So, it’s the combination of the fact that you’re serving something beyond yourself. And the challenge of leadership when you’re leading huge numbers of people, all of that together is why you stay with it.

Your sense of duty, which is obviously very powerful, where does it come from?

Norman Schwarzkopf: I think it comes from West Point, and my father. My father was a truly selfless public servant, both in his military career and in his police career. He believed very strongly in the motto of West Point, “Duty, Honor, Country.” I learned the principles of duty, and honor and country at West Point, and duty was one of the most powerful. Robert E. Lee said, “Duty is the sublimest concept of them all.” It’s the sense of duty that drives you sometimes. It’s the sense of duty that keeps you going sometimes when things get very, very rough. It’s this attitude: well hey; somebody’s got to do it. And if you don’t, who will?

Your dad had such a strong influence on you. Did he live to see some of your great success?

Norman Schwarzkopf: No. He lived to see me graduate from West Point, and I can honestly say that was probably the proudest day of his life. But he died shortly thereafter, so he never saw his son go beyond the rank of lieutenant.

I take it that they were supportive of your career, though?

Norman Schwarzkopf: Oh, yeah, I think so. I could have gone in any branch of the service I wanted to. In those days, when you graduated from West Point, there was no Air Force Academy, so 20% of the class could go in the Air Force, if they wanted to. I’ve got to tell you, my father was absolutely appalled that I picked the infantry. I think he thought I was going to pick the Corps of Engineers, or go into the Air Force, or something hi-tech like that. When I picked the infantry, he never did really understand that.

I think he would have eventually.

Norman Schwarzkopf: Now he would have, sure. But at the time, I think he thought I was crazy.

Correct me if this is a legend. Your one-time roommate, former General Leroy Suddath, insists that even at West Point, you predicted that you would lead an American army into combat, and probably in a decisive battle for the nation. Do you remember that?

Norman Schwarzkopf: That may be stretching it a little bit. But I will tell you this: I did not come into the Army to be a lieutenant, or a captain, or a major. I always thought I was going to be a general. At least I intended to be a general. If I started pumping gas, I would want to be the CEO of Shell Oil. Okay? So I always aimed high, my sights were always set very high.

I remember in the History of Military Art, which is a course that I loved at West Point, where you studied old bibles and everything else, I admired fellows like Alexander the Great, and Julius Caesar and Napoleon. Not everything about them, certainly, because they had some very bad characteristics also, but I admired their accomplishments. Robert E. Lee, and Ulysses S. Grant, and right on up the line. It’s funny, you almost admired the ancient ones more than the modern ones, because you didn’t know much about the ancient ones, except their accomplishments.

Was Hannibal another one that you admired?

Norman Schwarzkopf: Hannibal of course, coming across the Alps with his elephants and defeating the Romans. And the most famous battle of all was the Battle of Cannae. Anybody who has ever studied military history knows this battle of annihilation. When it was over, they piled up the jewelry alone from the Romans that had been slain and it was mountains of jewelry.

Isn’t there a danger that a general with your training, and expertise, and responsibility could suffer from bloodlust? From a desire to go to war?

Norman Schwarzkopf: I don’t think so. I can’t speak for other generals, but the people I know are not that way. Any general who’s worth his salt cares very much for his troops. Any general who’s worth his salt knows that war is not a Nintendo game, war is not something that’s fought by robots. He knows that war is fought by soldiers, by people. That liberty is bought by the blood of soldiers, and the sacrifices of these people.

So, I don’t know of many generals that are warmongers. There may have been in the past, but the modern generals that I know are just the opposite. They will go to extreme steps to avoid war, because they know just how bad it is. There’s not a general out there today who didn’t go through the Vietnam experience.

In my case, I happened to go through the Vietnam experience twice, and also Grenada. So we know the horrors of war. And I think that probably you will find that we are greater pacifists than most people you would meet. On the other hand, as I say, you have this sense of duty. And when the time comes when you must go to war, I think we also understand the way to get it over is to do it as quickly as possible. To bring all of your power to bear and get the darn thing over, and that’s another way you save lives. If war is inevitable and you’re going to have to fight it, then the smart way to fight it is to use everything you have and get it over with.

Don’t let it get long and drawn out. That’s why we lost 57,000 people in Vietnam, because that war just dragged on, and on, and on, and piecemeal commitments, and fighting under all sorts of restrictions, and that sort of thing. That’s not the way to fight a war.

Let’s talk a little bit about your service in Vietnam. How long were you there?

Norman Schwarzkopf: Two years altogether. For a year in 1965, and then again in 1970.

Tell us about ’65. How did that commission come about? Weren’t you teaching at the time?

Norman Schwarzkopf: Yeah. After West Point I went to graduate school and got a Master’s Degree. I returned to West Point as an instructor in Engineering Mechanics but more and more Army officers were being sent to Vietnam, mostly to be advisors to the Vietnamese. I had graduated from West Point to be an infantryman, not an instructor, and I felt that’s where I belonged. So, I volunteered to go to Vietnam. And as luck would have it, I got to go that time.

I had a terrific experience over there. Probably one of the most self-fulfilling experiences I’ve ever had, because there was no gain in it for me at all. I was making a tremendous sacrifice for no personal gain. Sometimes that can be one of the most self-fulfilling experiences you ever have.

I went back to West Point to finish my teaching career, and went to Fort Leavenworth. I had gotten married in the meantime, but the war was still going on. I had learned a great deal in my first tour, and I felt, because I had learned so much, that perhaps I could save some lives by going back the second time. So I volunteered to go back a second time, and spent a year over there again.

On that second tour, you witnessed two very tragic incidents. I wonder if you could tell us a little bit about them. In the book Friendly Fire, by C.D.B. Brian, it’s recounted that you lost eight men.

Norman Schwarzkopf: Yeah, we were stretching out beyond the limits of our artillery, so we moved our artillery forward. Because one of the things that gave us an advantage over the enemy is we did have our artillery supported. So we never wanted to go outside the extreme range of the artillery.

And one night while they were firing the artillery, it just fell short and came in and killed some people in my unit. It’s a terrible thing when it happens, it’s twice as difficult to explain to the troops, and three times as difficult to explain to the families of the troops. That was the incident.

There was one outstanding young man who was killed, and his parents could never really reconcile themselves to what had happened. They were convinced that there was some kind of cover-up. You know, we had casualties in this war, from our own fire, too. And now we see the same thing all over again, the agony of the family.

In this war it war even tougher, because there were so few casualties to begin with that anyone who lost a loved one kind of feels cheated. So few people were lost, why did it have to be my son, or my husband, or my father? When they find out subsequently that they were killed by the fire of their own side, that makes it doubly hard to live with.

It was a tragic situation in the case of the Mullens in Vietnam, and it’s a tragic situation when it happens today.

I gather that you personally felt these losses very deeply.

Norman Schwarzkopf: Yeah. If you lead men in battle, I don’t care whether you’re a sergeant, or a second lieutenant, or a four-star general, they’re your people. They’re your troops, men and women, I should say. They’re your troops. So, the loss of every single person that’s ever been under my command in battle has always hurt. Even though our losses were so few in the Gulf War, we still suffered losses, and I still grieve for every one of them. I wish we hadn’t lost anybody.

I have an old friend who was a pool reporter with you. He said that you inspire incredible morale among the troops. He saw you moved to tears by the friendly fire deaths. He thought that was very moving, that you show emotion.

Norman Schwarzkopf: I think if you believe something, you should believe it passionately. To be a good leader you have to lead passionately. And I’m a passionate person. I feel very, very strongly about things. I’m an emotional person. The tragedy of losing young men and women’s lives is tough enough to swallow. To find out that it was preventable is even tougher.

In May of 1970, there was a very dramatic minefield rescue. You were decorated for that. Could you tell us what happened?

Norman Schwarzkopf: The area we were in happened to be the same area as the terrible My Lai incident. I was always convinced that the great unanswered question was what the role of the Thai commander had been during that time. He had subsequently been killed, so there was no way you could answer that, but incidents like that are preventable.

We had an awful lot of mine incidents when we first moved into the area. It was a heavily mined area and my troops weren’t mine-wise, yet. Every time somebody hit a mine, if I was in the area, I would always fly in, in my helicopter, land right there on the ground, and put the casualty on the helicopter, because that got him back to the hospital about a half an hour quicker than they would ordinarily. The other reason was to go around and just talk to the troops, because the mines are an insidious sort of thing.

If you’re out and you shoot at the enemy and he shoots back at you, and you take some casualties, they’re not acceptable, but you do understand that at least there was an exchange that caused it to happen. When you’re walking along and all of a sudden a mine goes ‘boom!’, and you see one of your friends killed, or lose a leg, or something like that, there’s no way to retaliate. That tends to fester inside. So, I would go in to try and understand all that.

In this one case we’d had a mine casualty and I flew in and used my helicopter to Medevac him, and I was on the ground. Then, of course, we had another mine casualty. We were right in the middle of a minefield and I had to do something about it. That’s what that was all about.

What did you do about it?

Norman Schwarzkopf: The soldier was lying on the ground screaming, and I was afraid that he was going to set off more mines. Or, worse yet, he had a badly broken leg, and I was afraid that he was going to cut the artery in his leg and die. So I had to go over there and settle him down. There was nobody else to do it, so I had to walk through the minefield. Believe me, it wasn’t a heroic act at that time, it was something that somebody had to do, and I was the man in charge.

Did you experience any sort of moral dilemma about the Gulf War?

Norman Schwarzkopf: No. You know why? The whole world told us we were right. There were 40 different countries involved in that coalition, in one way or another. We got letters from all over the world. We started getting 100 tons of mail a day when we first got over there. By the time the holidays rolled around, we were getting 400 tons of mail a day, and almost 100 percent of that mail was positive, saying, “You’re doing the right thing.”

After the war was over, one of my commanders said, “You know, if we had had their equipment and they had had ours, we still would have won, because of the will within our soldiers.” Our soldiers knew that what they were doing was the right thing. Rule 14.

A great achievement of this war is the way that you got Arabs, French, British, Americans, and so on, to work so cohesively together. Your own skills as a diplomat obviously came in there.

Norman Schwarzkopf: I started honing those skills when I was a young man in Europe. I know how to work with people of all nations, and all beliefs. But don’t forget something else: we all had a common goal. We all knew exactly what it was we wanted to do, and that was get Iraq out of Kuwait. It was easy to get people to focus on the goal. When things came up that were not part of the goal, you put that aside. That may be a problem, but it’s not a problem that we have deal with right now. What we need to do is stayed focused on our own.

Especially when you consider the different nationalities of the forces that you were working with. Did you have enough time to prepare for this war? Would you have liked more time?

Norman Schwarzkopf: I had a lot of time to prepare for this war. Let’s face it, the gauntlet was thrown on the second of August, and we didn’t attack until the 17th of January. It would have been easier if it had been a little bit closer to home. We were about as far away from home as we could possibly be. Therefore, building up the necessary supplies and equipment and getting the troops over there wasn’t the easiest thing in the world.

Are you disappointed that Saddam Hussein held on to power after the war?

Norman Schwarzkopf: No. I could give you some very, very good arguments why it’s in the best interest of the United States and the entire rest of the world for Saddam Hussein to still be there, from a strategic standpoint. Now, from a purely emotional, personal, emotional standpoint, sure, I’d love it if he weren’t there, but he’s irrelevant. If you were to ask me one of the few mistakes we made in this war it was to so personalize the war in the form of a guy named Saddam Hussein. That now some people are looking at it and saying we really didn’t win because Saddam Hussein is still alive, that’s not true at all. It was a great victory because we did accomplish not only our military objectives, but our strategic objectives. What’s more important, today, right now, we have the greatest opportunity for peace in the Middle East we’ve had in my lifetime, my entire lifetime. Talks are ongoing right now between the Israelis and the Arabs and the Palestinians. You’ve just seen an incredible outcome in an election in Israel that’s going to affect the peace process. The peace process is ongoing and all of that is a direct result of the outcome of the Gulf War. It’s a direct result of the fact that Iraq is no longer a player over there. They’ve become irrelevant in the politics of the Middle East, and that’s important to the world.

What makes for a great leader? What are the qualities that are absolutely necessary?

Norman Schwarzkopf: Character, competence, selfless service, caring about people. I mean, really caring about people. I’ve known a lot of leaders who said, “Oh, boy, I really care about my troops,” and they didn’t give a damn, when it really got right down to it. But as I say, all of those things, I think go into the equation of a leader. I said earlier, passionately caring about your cause, whatever it might be.

Doesn’t a general need a strong ego?

Norman Schwarzkopf: Any leader needs an ego. If you’re not confident in yourself, how can you expect anybody else to have confidence in you? One of the most important things about a great leader is this thing called selfless service, that I mentioned earlier. You’re not doing it for yourself, you’re not doing it to stroke your ego, you’re doing it in spite of yourself.

The victory over there has changed your life radically. How has the scrutiny and the attention affected you and your family?

Norman Schwarzkopf: Well, you don’t have a private life anymore, that’s the bad news. The good news is that you have a wonderful group of grateful Americans out there that come to you every single day, every single hour, every single minute and tell you that.

We’ve talked about this as a family. We’ve come to a recognition that our lives have changed forever. But we’ve also come to the recognition that it’s for all the right reasons. When you’ve just signed the 800th autograph, and 801 comes up, and you’ve got bad writer’s cramp, you just remind yourself that it’s because people feel good about their country, they feel good about themselves, they feel good about their armed forces.

When they see you, you’ve reminded them of that, and that’s why they come to you. Then you sign number 801, and go on. You don’t say no to them, you say yes to them, because it’s for all the right reasons.

Living in a fish bowl means you’re constantly analyzed by the press. For the most part you’ve come out smelling like a rose. Has there been some criticism that irked you, or that you felt was just perhaps?

Norman Schwarzkopf: Oh, I could go on about that forever. It’s one of the terrible things about this country, that the minute people become public figures, there’s members of the press who do everything they can to start destroying them, to tear them down. I never quite understood why. Some of the things, many of the things that have been said about me are just blatantly untrue. Some of the stories in the Gulf were manufactured by members of the press, and they wouldn’t let go of them. Even when it was proven to them that the story was untrue, they continued to spread it around anyhow, only because they refused to admit that they might be wrong. So, I think it’s too bad that that happens in this country because it keeps an awful lot of good people from serving this country, that otherwise would serve this country. But it goes with the territory. The important thing is, you can’t let it get to you. You stay focused on the donut, instead of the hole. I honestly could care less what the press says about me. It’s important to me what the American people think about me. And the American people come up and tell me over and over again how they feel about me. And if you stay focused on that — and I would also tell you what’s very important to me, most of all, is what my family thinks about me. My family knows me for what I am and who I am, and that’s all that counts. Thank God, my kids think I’m a pretty good dad. As long as they believe that, that’s good enough for me, I don’t need anything else.

Any of them following in your footsteps?

Norman Schwarzkopf: No, not right now. I’ve got a daughter who’s 21, another daughter who’s 20, and a son who just turned 15. He is has not exhibited any interest in the military, and that’s okay.

One of the things I say to young people is, dare to be yourself. I want them to dare to be what they want to be. I don’t want to build a box and force them into a mold, and make them do something because it will bring them fame, or fortune. I want them to do something because it will make them happy.

Would you want your son to go into the military?

Norman Schwarzkopf: No, and I’ll tell you why. I think that sons of notorious generals don’t stand a chance. Everything that they do well and get credit for, everybody says, “Of course the only reason they’re getting credit is because of their old man Schwarzkopf.” And then the minute they stub their toe everybody says, “Well, gee, they sure can’t fill their dad’s footsteps.” That puts a terrible burden on a younger person. As I say, I want my son and daughters to be what they want to be.

Do you have a critic out there who you do rely on?

Norman Schwarzkopf: My wife, my children, my friends, myself. I’m my own strongest critic. I am much tougher on myself than anybody I know, consistently.

I gather that that’s a positive thing in your eyes.

Norman Schwarzkopf: Of course. People who think they’re right all the time scare the living daylights out of me, they really do. We all ought to recognize that none of us are infallible. We’re all capable of making mistakes. That’s okay, because you’re human. What’s important is to learn from those mistakes.

That’s very good advice, because I think a lot of people feel like they’re too self-critical, or they can’t make mistakes. They’re very rigid.

Norman Schwarzkopf: I give a lecture and it goes like this…to leaders. I say, how many of you people learned something about how to do your present job by screwing it up the first time? I say, my goodness. How can you then possibly say, no mistakes in this outfit? How can you not allow yourself mistakes? You’re not giving yourself a freedom to fail because I don’t believe in the word failure. You’re giving yourself the latitude to learn. I’ve learned most things I know how to do well, probably, by screwing it up the first time.

What do you feel is the next danger area in world conflict?

Norman Schwarzkopf: I think it’s obvious. The Gulf War was a typical indication of what’s happening in the world today. You are not going to see major armies confronting each other along a battle line, like you did in World War I, like you did in World War II, like we did in the confrontation between NATO and the Warsaw Pact. What you’re going to see is regional conflicts, regional strifes, which tend to get bigger and bigger and suddenly spill over their boundaries and in fact, impact the rest of the world and the rest of the world gets drawn into it. That’s the sort of thing you’re seeing today in Yugoslavia. That’s the sort of thing you’re seeing in the former Soviet Union, and that’s what we have to guard against. My answer to that is, get involved in it while it’s still peaceful, before it turns into a war because you don’t want to get dragged into these kinds of conflicts. But, let’s face it, when we got involved in the Gulf in the Tanker War, when we got involved in the Gulf War, it was essentially a regional conflict that got too big and affected the rest of the world, and the rest of the world was dragged in.

Is the future for the military going to change a lot, as a result of the changes in the Soviet Union, and so forth?

Norman Schwarzkopf: I don’t think it’s going to change a lot. No more so than the future of this entire country is going to change. Since the end of World War II, our foreign policy has been dominated by confronting Communism throughout the world. Our military strategy has been fighting the Soviet Union. Our business strategy has been very much dominated by this thing. Now this is gone.

So, the central focus, the way of doing business in our government, in our world, in our military, is going to be refocused. That should change a lot of things.

But the fundamental mission of the armed forces is going to stay exactly the same: defend the country. We shouldn’t get so euphoric that we decide to do away with the armed forces. When I graduated from West Point in 1956, if anybody had come to me and said, “Lieutenant, where do you expect to fight your wars?” I doubt very seriously if I would have said, “Oh, it’s very clear, I’m going to fight in Vietnam, Granada and Iraq.”

We don’t know where the next war is going to be, and we can’t just say, nothing is going to happen, therefore we ought to do away with the military.

What can you tell young people about the positive value of serving in the military?

Norman Schwarzkopf: The first thing about serving in the military is, you’re serving something other than yourself. That’s very important. I think you get a great sense of satisfaction when you server something better than yourself. That’s number one.

Number two, it’s an exciting career. I’ve traveled all over the world, lived all over the world, learned many, many things. I’ve enjoyed it, from the excitement of world travel, and the adventures that I’ve had. I’ve met some wonderful people, and I’m associated with great people. People that have been very, very close to me in the past and will be for the rest of my life, I’ve met in the military. I’ve enjoyed my military career. My family enjoyed my military career.

I would imagine there’s a visceral thrill to doing the work you do sometimes, too.

Norman Schwarzkopf: Sometimes it’s visceral thrill, and sometimes it’s agony.

Is the military changing? Should it change, with regard to women in the military?

Norman Schwarzkopf: Women are very much a part of the military. They were very much a part of the Gulf. They already are integrated into the armed forces to a great extent. The big conflict now is over the role of women in combat.

This is a question that’s being argued in the wrong arena. It’s being argued in the arena of equal rights, and that’s not the arena it should be argued in. It should be argued in the arena of national defense, and what’s best for the defense of this country.

I talk about the problem this way — take an armed forces that has a unit of 1,000 infantry men. These are the folks that fight with bayonets, and roll around in the mud, and the trenches. Now, oppose them with an organization of 1,000 people, 50 percent of whom are female. Is that really in the best interest of that second country to send that organization against an organization of 1,000 men with knives to fight in the trenches?

We must do what’s in the best interest of this nation for the defense of this nation. At the same time, we must do everything we can to make sure that women in the military have the same opportunity that men in the military have to get ahead. But it’s got to be a balanced approach, and not one that just blindly says 50 percent of the entire military must be female, for no other reason than because 50 percent must be female. That’s not the way to handle the problem.

Having said all of that, I’ve got to tell you that the women in the Gulf did a magnificent job. They had it much tougher than the men, because of the cultural sensitivities, and yet they handled it with ease, and they did an absolutely fantastic job. I am very much in favor of women in the military.

I happen to be one of those people that’s in favor of women in the cockpit. I have no problem with women flying a fighter plane. If they’re going to fly Medevac helicopters in the heat of battle, why can’t they fly an Apache helicopter?

That’s not shared by many of my friends in the military, but I happen to be one of those people that’s in favor of women in the cockpit.

Is the military confronting race issues better now than it used to? Is there more work to be done?

Norman Schwarzkopf: Listen, the armed forces dealt with race before the entire rest of this country did. Today in the armed forces, racism and prejudice has essentially been eliminated. All you have to do is go out and look at the number of black soldiers you have in the military who are there because they feel that they have a far better opportunity for advancement in the military than they do anyplace else. The proportion is much greater than you find anyplace else.

Colin Powell, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff happens to be the highest-ranking man in the entire U.S. military, and he happens to be a black soldier. I don’t even look at soldiers as being black, white, red, yellow, green, purple, or pink, and most of my friends don’t. But I’ll tell you one thing, if we ever run into anybody who does, we get rid of them. We don’t tolerate prejudice in the military.

And I’ll tell you another thing, we have been going after sexual harassment in the military long before the civilian world even discovered what the term was. We came to grips with this many years ago when we started bringing more and more women in the military and found out that they were in fact being harassed. We have been dealing with that for quite some time in the military in a much stronger way than I think our civilian contemporaries have.

What about the drug problem?

Norman Schwarzkopf: The drug problem is almost eliminated in the military, and I’ll tell you why. This thing called random urine testing. We have a unique situation in the military now where people want to be there, it’s an all-volunteer force. One of the interesting things about the Gulf War is the fact that all the people there volunteered. They either volunteered to be in the active force, the National Guard, or the reserves. Everybody in the military today wants to be there, and they don’t want to be kicked out.

We’ve made it very clear that we conduct random testing, and that if a person comes up positive, they’re kicked out of the military, it’s just that simple. We don’t tolerate drugs in the military today. All the surveys we have, and everything else, show that we’re a lot cleaner in the military than we ever have been.

By the way, the same thing happens to apply to alcohol. It used to be that drunkenness, and DUI’s, and things like this were tolerated. They’re not tolerated anymore. If you want to get in trouble in your military career, just come up with one DUI. It’s considered a very, very serious offense, and grounds for elimination.

If you could have a conversation with any great military leader of the past, who would that be? If we could eavesdrop, what would you ask?

Norman Schwarzkopf: It would be my dad, and I’d want him to know what I’ve done with my life.

That must be very frustrating. What do you know now about leadership that you didn’t know when you graduated West Point?

Norman Schwarzkopf: It’s not a perfect world. When I graduated from West Point I saw things very much in shades of black and white. And I’ve come to understand that – and I also demanded a great deal of myself then as a young man in shades of black and white. You had to do everything right, you couldn’t do anything wrong. And that’s not what’s life is all about. But I guess the thing I probably learned more than anything else is: self-fulfillment is the most important thing of all. Being happy with what you do, feeling good about what you’re doing is probably the great secret to life. You don’t measure a person’s success by what they take out of life, you measure a person’s success by what they leave behind. You can have all the money in the world, you can have all the power in the world, you can have all the prestige in the world, none of that’s important. What’s important is what you do with it when you have it. That’s what’s important. That’s what leadership is sort of all about.

What advice would you give a kid who is kind of insecure about the future, about succeeding in life?

Norman Schwarzkopf: Trust yourself. Life is worth living. Life is worth living and life should be lived. There’s more good out there than there is evil. Man is basically good. Mankind is basically good. I guess 30 years from now you’d say “personkind.” I don’t know. What I’m saying is, people are good. People are great. Enjoy them, and enjoy your life. And again, it’s the point I would make to any young people, it’s what I talk about with my children. People should dare to be themselves. Don’t be something because somebody else tells you that’s what you should be. Don’t be a brain surgeon if you want to be an artist. You’ll never make any money as an artist; you could make a fortune as a brain surgeon. But don’t be a brain surgeon to make money. If you want to be a brain surgeon because you’re really interested in saving people’s lives, that’s a reason to be a brain surgeon. Most of all, be yourself. Dare to be yourself. Take your God-given talent and use it the way you feel you should use it. Don’t let anybody steer you down the path of, this way you get more money, this way you get more prestige, this way you get more success, because I’ve seen so many people in my lifetime who burn out. They get all of these things that they originally strive for, and then there isn’t anything else. So, what do I do now? Because the one thing they don’t have is it’s not here. It’s not in their heart. They don’t have self-fulfillment. They don’t feel good about themselves. They don’t feel satisfied because they measure their lives in terms of the next promotion, or the next award, or the next pay raise, or whatever it is. And one of these days, all that’s over with.

We talked earlier about duty, and how that drives you and has driven you throughout the course of your career. Now you mention self-fulfillment. The two are not mutually exclusive at all.

Norman Schwarzkopf: Of course not. The most fulfilling times I’ve had were times when I was doing my duty, with no personal gain for myself. I got nothing tangible from it, and yet I got everything from it, that’s the point.

Looking ahead to a hundred years from now, when somebody is writing about the life of General Norman Schwarzkopf, what are the things you would like brought out? What are you most proud of?

Norman Schwarzkopf: A man does not get to write his own epitaph. But if I were to write mine it would say the following: He loved his family, and he loved his troops, and they loved him — period.

Thank you for taking the time to talk with us today, General. It has been an honor and a pleasure.

Norman Schwarzkopf: You’re welcome.