Remember, there are no victories in conservation. You may have a temporary ‘looks good.’ Suddenly things change and the fight begins all over. So we’ve got to continue fighting.

George Schaller was born in Berlin, Germany and spent his early years there, surviving the devastation of World War II. Following the war, he and his mother moved to the United States to live with an uncle, arriving in Missouri in 1947. Exploring the woods and streams near his new home, the teenage Schaller discovered the joys of observing wild animal life. He kept a pet raccoon, collected snakes and lizards, and not surprisingly, gravitated towards a career as a natural scientist.

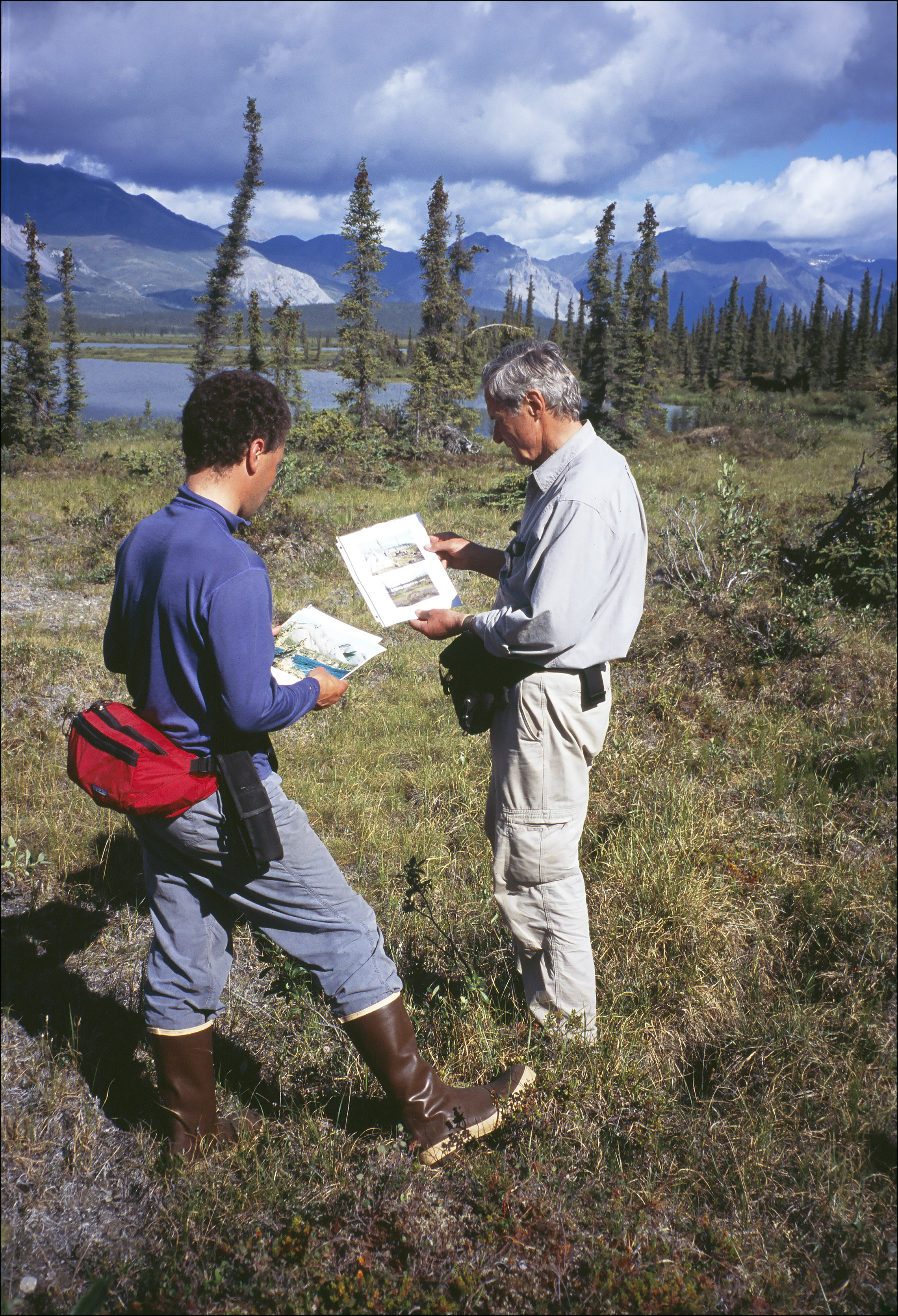

He enrolled at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks, where he volunteered to work in the wildlife laboratory. As an undergraduate, he undertook his first zoological expedition, recording the movements of birds as they travel back and forth from Russia to Alaska. He graduated in 1955 with degrees in both zoology and anthropology. Shortly after graduation, he joined the renowned naturalists Olaus and Mardy Murie on a comprehensive survey of the wildlife of northeastern Alaska.

With the Muries, Schaller had the opportunity to observe wolves, bears, caribou and other creatures of the region. The data collected by the Murie expedition, including Schaller’s contribution, informed the federal government’s decision to permanently protect the habitat of Alaska’s most vulnerable species. The northeast corner of Alaska was designated the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) by order of President Dwight Eisenhower. Until the Murie expedition, Schaller might have considered a conventional career as an academic zoologist, but from then on, he was determined to work as a field biologist, studying wild animals in their native environments.

Schaller continued his study of bird behavior as a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. In 1957, the year he completed his master’s at Wisconsin, he married Kay Morgan, who would accompany him on his future travels around the world. At Madison, his professor John Emlen proposed that Schaller join him on an expedition to study the mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei) of East Africa. At the time, the image of gorillas in the popular imagination was one of savage creatures, violent and aggressive. This idea, based on a small body of anecdotal experience reported by hunters and explorers, had been widely disseminated through fiction and films. From his own experience with wolves and bears in the Arctic, Schaller knew that wild animals seldom attack humans unless provoked. He suspected that the legend of the violent, hostile gorilla was more myth than fact. Schaller procured a grant from the National Academy of Sciences to join the expedition.

In 1959, Professor Emlen and the 26-year-old Schaller, along with their wives, traveled to the Virunga volcano region, an area intersected by the present-day boundaries of Uganda, Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. After six months in the wild, Emlen and Schaller established an appropriate site for long-term observation of the mountain gorillas. The Emlens returned to Wisconsin while Schaller and his wife remained. Over the following year, they became intimately familiar with the gorilla and its true nature, which was far gentler, friendlier and more cooperative than popular lore suggested. The great apes typically live in bands of five to 27 members, under the leadership of one mature male gorilla. Relations among members of the band are typically gentle and affectionate. As Schaller would later write, “No one who looks into a gorilla’s eyes — intelligent, gentle, vulnerable — can remain unchanged, for the gap between ape and human vanishes; we know that the gorilla still lives within us.” When George and Kay Schaller returned to America, his work with the gorillas was carried on by the American researcher Dian Fossey.

In 1962, Schaller received his doctorate in zoology from Wisconsin and accepted a fellowship at the Behavioral Sciences Department at Stanford. The following year, his first book, The Mountain Gorilla — Ecology and Behavior, was published, and he became a research associate at Johns Hopkins University. In 1964, Schaller shared a more personal story of his time in Africa in a book for the general public, The Year of the Gorilla. In 1966, he joined the New York Zoological Society as a research associate and zoologist. The Society, founded in 1895, is now known as the Wildlife Conservation Society. George Schaller’s association with the Society has lasted more than half a century.

Schaller’s work with the mountain gorillas attracted the attention of the government of India, which invited him to carry out a similar study of the endangered Bengal tiger. Once again, Schaller and his wife chose to live in close contact with an animal of fearsome reputation. Schaller has always refused to carry a firearm while meeting with these animals because he believes the animals perceive a human carrying a weapon as a threat, whereas human beings who live nearby and maintain a regular routine without disturbing the animals can gradually earn their trust. He shared his observations of the wild tiger and its prey in his 1967 book, The Deer and the Tiger, and in The Tiger: Its Life in the Wild (1969).

The Schallers, now a growing family, returned to Africa to study the lions and other wild cats of the Serengeti, a spectacularly diverse ecosystem straddling the borders of Tanzania and Kenya. George Schaller published his findings in his 1972 books Serengeti: A Kingdom of Predators and The Serengeti Lion: A Study of Predator-Prey Relations. The latter book won the National Book Award in Science. He continued his discussion of lions with the public in Golden Shadows, Flying Hooves and Wonders of Lions, co-written with his wife, Kay.

Although Schaller and his family loved their life in the Serengeti, he eagerly accepted an opportunity to study the animals of the Himalayas. The Schallers relocated to the Dolpo region, which lies within the borders of Nepal, while its population is predominantly Tibetan in language and culture. In the Himalayas, he made groundbreaking studies of the rare mountain goats and sheep, a story he shared in Mountain Monarchs: Wild Sheep and Goats of the Himalayas (1977). He was one of the first Westerners in the 20th century to glimpse the elusive snow leopard in the wild. Schaller spent the late 1970s in Brazil, studying the jaguars and alligators of the Amazon, as well as the capybara, the world’s largest living rodent. In 1979, he became the director of Wildlife Conservation International, the international program of the New York Zoological Society (now known as the Wildlife Conservation Society).

The following year, the government of China invited the World Wildlife Fund to study the endangered giant panda bear in its natural habitat. At the time, their dwindling numbers were attributed to the increasing scarcity of their staple food, bamboo. The Fund recruited Schaller to lead the effort. The Schallers spent the next two years in Wolong Nature Reserve in Sichuan, China, one of the last redoubts of the iconic black and white bear. After eight months back in New York, the Schallers returned to China for another two years to investigate the other remaining panda habitat areas. With close observation, Schaller determined that the hunting and capturing of the highly prized animal was the actual cause of their declining numbers, and he initiated a campaign to preserve the panda population in the wild. His 1985 book, The Giant Pandas of Wolong, helped alert the world to the threat of extinction facing the species. Schaller’s efforts have led to increased protection of China’s pandas. Since he began his work, the population of pandas in the wild has increased by 45 percent.

Further travels in Asia have taken George Schaller from the deserts of Mongolia to the jungles of Indochina. He has found living specimens of species long thought extinct, such as the Vietnamese wart pig and the Tibetan red deer. And in Laos, he discovered a previously undocumented species, the saola, a forest-dwelling bovine. He has also worked to protect the rare Tibetan antelope, the chiru, which had been nearly hunted to extinction for its coveted wool.

In 1993, the New York Zoological Society changed its name to the Wildlife Conservation Society. Schaller has continued his work with the organization, an association that has lasted for half a century. In 2006, he helped form Panthera Corporation, an organization exclusively dedicated to the conservation of the world’s 40 wild cat species and their ecosystems. It implements global strategies for the most imperiled large cats: tigers, lions, jaguars, cheetahs, pumas, and leopards, including the snow leopard.

In every country where he has worked, Schaller has recruited local scientists and volunteers to conserve native animals and their habitats. In 2007, he helped lead a multinational effort, coordinating with the governments of Pakistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and China, to create a Peace Park to preserve the habitat of the Marco Polo sheep, the world’s largest species of wild sheep, whose spiral horns can measure six feet long. His efforts have also led to the creation of wildlife preserves in the Amazon, in Nepal, and in the Hindu Kush region of Pakistan, as well as the Chang Tang Nature Preserve in northern Tibet, three times the size of any wildlife refuge in the United States.

To date, he has written more than 15 books, including Tibet’s Hidden Wilderness and Tibet Wild: A Naturalist’s Journey on the Roof of the World. He has received the Lifetime Achievement Award of the National Geographic Society, the Gold Medal of the World Wildlife Fund, the International Cosmos Prize, and the Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement. In his 80s, George Schaller continues to serve as an adviser to the Wildlife Conservation Society and the Panthera Corporation. Although they have spent more of their lives in the wilds of Asia, Africa, and South America than they have at home, George and Kay Schaller now make their home in New Hampshire.

For months and years at a time, George Schaller has lived among the most beautiful and fascinating creatures on Earth, among them the lions and gorillas of Africa, the tigers of India, the jaguars of the Amazon, and the giant pandas of China. His painstaking observations of the daily life of animals in their natural habitats have yielded priceless insight into the breathtaking variety of life on Earth.

Until he lived among the mountain gorillas of East Africa, they were thought to be violent, aggressive brutes; hunters and explorers avoided them altogether or killed them on sight. Living among them from day to day, he found them cooperative and affectionate in their relations with one another, gentle and friendly with humans who win their trust. In addition to his exhaustively thorough scientific studies of the animals he has lived among, George Schaller has shared his discoveries with the larger public in a series of captivating books for the general reader.

His pioneering studies of China’s giant pandas have helped to arrest their threatened extinction. He has done the same for the giant yak and snow leopard of the Himalayas and Central Asia. His advocacy for preserving the natural ecosystem where wild animals flourish has saved whole species from extinction and preserved vast stretches of wilderness around the world so that we can share our planet with these majestic creatures for generations to come.

You’ve enjoyed being outside and watching animals since you were very young. Were you already thinking of being a biologist and a conservationist?

George Schaller: I enjoyed being out but not just to watch, watch, watch. That came when I went to the University of Alaska, and I helped the graduate students in the wildlife lab. And I went out with them, and I saw in detail what they were doing, that they were writing things down; they’re quantifying things. “How often does this animal scratch itself in one hour?” type of thing. I just said, “Hey, this sounds good. I want to do that.”

I like to be alone, watching things, wandering around the forest, seeing wildlife, seeing an owl sitting up in a tree. I just basically enjoy that. That’s part of my character, being somewhat of a loner. But conservation is a step forward. In the beginning, no, I didn’t think about conservation as such, but then, particularly when I went to the Brooks Range in 1956 with Olaus and Mardy Murie — he was head of the Wilderness Society, a well-known conservationist — and he said, “We’re here to do a bit of science, but especially, the precious intangible values of the area, it must be protected.” I’ve been fighting for that ever since.

What gives you the patience to watch the same animals, hour after hour, day after day?

George Schaller: Well, you want to try to understand an animal. If you have a dog, you stare at it and wonder what it’s thinking. The same is when you’re meeting a tiger. What is really going on in that tiger? And to even get close, you can never understand. I mean I have a hard time understanding my wife, but as far as understanding the tiger, by getting a lot of detailed facts, seeing the situation, I can get some impression of what kind of animal it is.

Humans are so varied in their personalities. You can’t always predict how they’re going to react. Are animals more predictable than humans in their behavior?

George Schaller: Animals, like humans, are individuals. They’re fairly predictable because it depends on your behavior. They can sense much better than you can what your intentions are. If you want to run with a gun, you have a tension in your body, an aggressiveness that an animal often can sense. Whereas, if you just accidentally meet an animal, hey, the animal realizes this is an accident and you back off, usually, but then there are individuals that for whatever reason — it can be genetic, it’s because people have harmed it — they will attack. Why do you think most animals run away when you see them? We’ve made them shy. If you’re nice to them, they wouldn’t be running away.

You’ve studied some of the most fascinating and charismatic animals — gorillas, pandas, jaguars, lions. You were the first to do major studies of these. How do you inspire people, when they’re not going to be the first, when they’re just following up on the groundbreaking work?

George Schaller: Studying something spectacular — finding out that gorillas are not ferocious, that they’re very kindly, that there’s nothing more pleasurable than sitting next to a wild gorilla and looking into its brown eyes — but it’s the long-term studies that help protect it. And by studying something spectacular, I can also raise the money to go continue the studies or start new studies. And also remember, you’re not just studying a tiger. You’re studying all the hoofed animals — the deer, the wild bison, and others that the tiger eats. Then you’re studying the vegetation that the herbivores eat. So you’re doing an ecological study of an area. But what do people pay attention to? Not what the deer does but what the tiger does.

At the time you studied gorillas, not much was known about them. Most of the information indicated these were very dangerous creatures.

George Schaller: People shot them usually.

That was the only information you had when you went to study them. How did you think you could get close enough to observe them for a year?

George Schaller: Having worked in Alaska with various species, you know that nothing is wholly ferocious. That if you do it right, if you go near them gently, if you make them realize that you mean no harm, they’re not going to be concerned. And the same with gorillas. Day after day, you follow them slowly, a group. You sit near them. Don’t stare at them. Look away. If they come near you, just sit quietly. And after a few meetings, they realize you’re no problem and that you come there day after day. You can see now that, in the tourist groups, the big problem is that the gorillas want to come and touch you. Well, that’s not a good idea, either, because people are full of diseases which they can transmit to the gorillas. But all these animals — lions, tigers, and so forth — they become very used to people. You’ve got to be a little careful because you never know if a tiger has had a bad experience with people and jumps at you. But I’ve met tigers — from me to you — and they’re both surprised and back off without any aggression on either side.

What do you do for a year watching gorillas? What do you look for?

George Schaller: I find a group. I recognize all of them individually, in the area where I worked, about 200 or so. Their faces, particularly the nose area, is very distinctive. So I’d check out who’s there. And the wonderful thing, in Rwanda, is you go out with the guides there now. The guides now know all the gorillas and can check and see what’s happening. But so I’d go, “How far have they gone? What is their main food that day? Are they meeting somebody? And what happens when they meet?” Usually, there’s aggression when two gorillas’ groups meet. Sometimes they mix and you don’t know — you want to know who is aggressive. Do you know their history? And so forth.

How long did it take before the gorillas accepted you and would let you just sit there and observe?

George Schaller: Usually, it took maybe ten to twenty meetings with a group. They live in tight groups, which makes it easy. You’ve got to get the big male to accept you because he’s the one that defends the group. If he pays no attention, the rest don’t pay attention, and then they get curious and come to you.

When did you get a breakthrough, when a gorilla would come near you or just sit down beside you and carry on?

George Schaller: The forest where I was working had a lot of trees with big low branches. So to see them better in the vegetation, I’d climb and sit on a branch. And the female gorilla climbed up and sat on a branch next to me. Well, we were both a little nervous. She’d look at me and then quickly look away. I’d do the same. So we sat there awhile, and then she climbed down and walked off. Now, that’s lovely. And then others started coming close when I’d come near. I didn’t encourage it, but I just stayed there. It got so I could sleep with them at night. I’d see where they’re going to bed down. I’d lie down a hundred feet away or so and spend the night to find out what goes on.

What about the tigers? Was it always in the back of your mind that you had to be more careful than you would if you were studying some other animal?

George Schaller: Actually, you know, I’m more worried about studying a bear than a tiger because a bear, its facial expressions are not as clear-cut as a tiger. You know what a tiger is thinking, but a bear, more difficult. So you have to decide what is best to do with these animals. And, for example, the tigers, where I worked in Central India — I was out all the time walking around. I’d meet the same tiger again and again. I’m sure they recognized me. I wore the same dirty clothes all the time. So again, the animals learn, “Hey, this guy’s no problem.” So they don’t make it a problem. In fact, they don’t necessarily run away. I’ve had them crouch ten feet away while I walked past and purposely not look at them.

With an animal such as the snow leopard, where you’re seeing tracks or picking up the feces to study it, more than actually seeing the animal up close, is it as satisfying?

George Schaller: For example, snow leopards live in open country. They can see you two miles away and hide. All right. My most wonderful encounters are when they accepted me. And I see them. They’re not running way. I watch them awhile. It’s dusk. I sleep right near them because they have a kill nearby and so they don’t run away. Well, to really feel that an animal accepts you, it’s one of the most satisfying things for somebody like myself.

You’ve fought hard to protect some of these iconic animals, like the snow leopard. Is it harder to sell the public on protecting less well-known species, like the Tibetan antelope?

George Schaller: People haven’t seen a Tibetan antelope — a beautiful animal. I was very fortunate, in that China, in recent years, has been truly interested in protecting some of these species and has set up reserves and started anti-poaching work. The poor antelope, of course, has been in big trouble because it’s got the finest wool in the world. During the 1990s, about 250,000 were killed on the Tibetan Plateau, the wool exported to India, and they make these lovely Shahtoosh shawls which ladies like to wear and buy at prices up to $15,000. Well, that market has gone down because countries are now more aware of this, and China has been protecting it. Borders are better patrolled. So it’s step by step. It takes time.

Do you think a number of species have a better chance at survival today because of your work?

George Schaller: It certainly helped in raising awareness by government and the public. But remember, there are no victories in conservation. You may have a temporary “looks good.” Suddenly, things change and the fight begins all over. We’ve seen this with elephant ivory. There was the big ivory, back 30 years ago, then things improved, elephants increased. Suddenly again, huge ivory market; now again, things are improving. So we’ve got to continue fighting.

There’s no finish line in conservation.

George Schaller: No.

You did the first observations of so many species, but you didn’t just leave it at that. You made sure the work continued after you left.

George Schaller: Right. The one thing that has happened in so many of these studies, whether it’s tigers, lions, pandas, and so forth — that’s been continued by other biologists, both foreign and local, and that’s ideal. So somebody continues the monitoring. That’s why these places like the Serengeti still exist, because there are people there caring about it.

When you were starting out, was the work more about satisfying your own curiosity, or were you already thinking of the impact your studies could have in the long run?

George Schaller: You realize early on that — you do a good scientific study and publish it, somebody will come on and continue that work with new questions, new answers. So this is an evolving situation, and it’s never a final one. So I was happy to do good studies, but then it turned into conservation, that I wanted to set up protected areas for these animals. You have a moral obligation, in effect, to help the animals that you study. Then the other very important step is that you find local graduate students in the country where you’re working, take them into the field, and get them enthusiastic about studying their own wildlife in their own country. That, in the final analysis, has given me probably the most satisfaction, when I look at some of these countries that I worked in.