I was born a writer. When that happens, you have no choice in the matter.

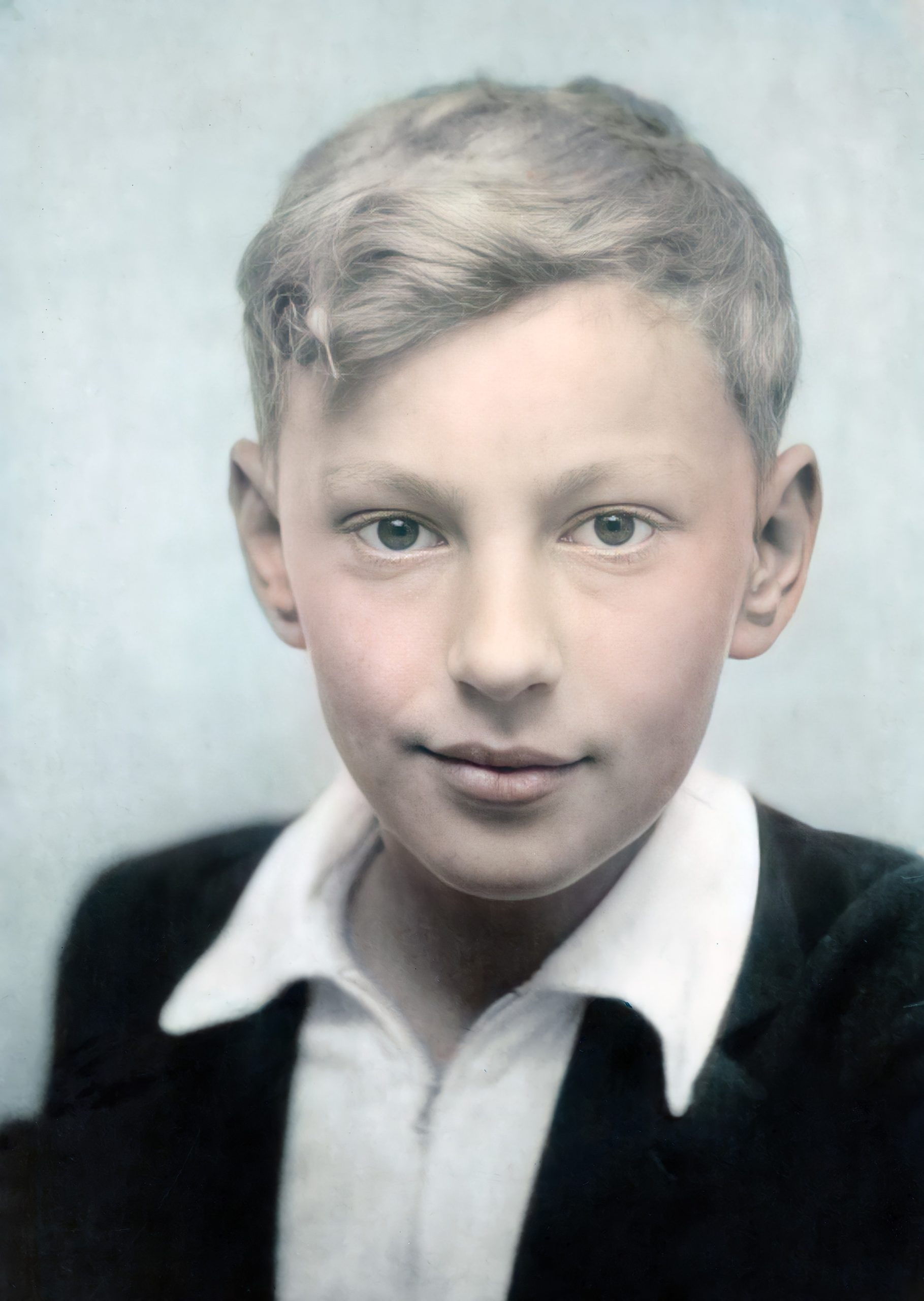

Eugene Luther Gore Vidal was born at West Point, New York. In his teens, he shortened his name to its more familiar form, Gore Vidal. At the time of his birth, his father, Eugene Luther Vidal, an officer in the United States Army, was serving as an aeronautics instructor at the United States Military Academy. As a cadet, the elder Vidal had been a star of the Army football team; he later competed in the decathlon at the 1920 Olympic Games in Antwerp, Belgium. After leaving the Army, Vidal senior became one of the pioneers of commercial aviation in the United States, involved in the founding of TWA, Eastern and Northeastern Airlines. He would also serve as Director of Air Commerce in the administration of Franklin Roosevelt.

Gore Vidal’s mother, Nina, was the daughter of Senator Thomas Pryor Gore. A Mississippian by birth, Senator Gore had traveled west as a young man and helped found the State of Oklahoma. He was one of the State’s first two Senators, serving from 1907 to 1921. He won re-election to his final term in 1930. Senator Gore had been blinded in a childhood accident and prevailed upon his wife and grandson to read to him from his large library. The young Gore Vidal read widely from this collection, feeding a love of history, politics, and the joys of language and narrative.

After her divorce from Eugene Vidal, Nina Gore married financier Hugh D. Auchincloss, and young Gore Vidal went to live with them at Merrywood, Auchincloss’s vast estate in Northern Virginia. Vidal’s relationship with his volatile mother was often strained, and she sent him to a succession of boarding schools: St. Albans School in Washington, D.C.; the Los Alamos Ranch School (later the home of the Manhattan Project) in New Mexico; and finally Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire.

Strongly influenced by the isolationism of his grandfather, the Senator, young Gore Vidal led his school’s chapter of the America First Committee, a national group opposed to America’s entry into the Second World War. With the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, opposition to American involvement in the war vanished, and immediately after graduation, the 17-year-old Gore Vidal enlisted in the United States Army. Vidal was assigned to duty as a warrant officer on a transport ship in the Aleutian Islands, where his ship encountered the fierce arctic storm known to the native Aleuts as a williwaw. Vidal suffered hypothermia, which severely damaged his knee. While recuperating in military hospitals he wrote his first novel, Williwaw. The book was completed when he was 19 and was published by E.P. Dutton when he was 20. Along with his contemporary, Norman Mailer, he was one of the first of the returning World War II veterans to be published. After his discharge from the army in 1946, Vidal joined E.P. Dutton as an editor and plunged into the literary life of New York City. His first novel had attracted attention; his second novel, In a Yellow Wood, about the dilemmas of a returning veteran, was also well-received, but Vidal soon chafed at the routine of the publisher’s office and felt suffocated by the ingrown literary set of New York. He had begun work on a third novel and wanted solitude to finish it. He decamped to Guatemala, where he believed his small savings would stretch farther and where he could write in peace. He bought a house in the old colonial town of Antigua and settled down to complete his novel.

Since adolescence, Vidal had weighed the choice of a career in literature or in politics. With his third novel, The City and the Pillar, the die would be cast in favor of a literary career. The book portrayed homosexual relationships in a nonjudgmental way, as a fact of nature. This broke an enormous taboo in American literature, where the topic had only been treated as a subject of shame and remorse. While a few fellow authors praised the book and it sold well, many critics loudly condemned what they regarded as the book’s immorality. The New York Times refused to review Vidal’s subsequent books for almost a decade; some publications even refused to print his name, much less review his books. Another novel completed in Guatemala, A Season of Comfort, disappeared in the face of a virtual blackout by the mainstream press.

Over the next few years, Vidal traveled between New York and Europe. Although his name was anathema to many in the press, his work was well-received abroad, and he continued to write novels on a variety of subjects. A Search for the King revisited a medieval legend; Dark Green, Bright Red portrayed an American-led coup in Central America. In 1953 he achieved an artistic breakthrough with The Judgment of Paris, setting a contemporary story against a background rich with themes from classical antiquity. In this book he truly found his own distinctive voice as a writer for the first time. His 1955 novel Messiah was a futuristic fantasy of a dictator who rises to power in the United States by exploiting the new medium of television. Despite Vidal’s great productivity and growing power as an artist, his work was studiously ignored by the American press.

In the mid-1950s, Vidal bought a large house on the Hudson River in Dutchess County, New York. Needing money to support this expensive establishment, he took on a variety of commercial ventures, writing a series of mysteries under the pseudonym Edgar Box. Unlike his serious fiction, these potboilers were very well-received in the press. He made a more unusual move by entering the new medium of original drama for television. At the time, many of the most popular programs were anthology shows, such as Studio One and Playhouse 90, broadcast live. Most serious writers in the ’50s shunned the medium, as their predecessors had shunned the movies, but Vidal seized the opportunity. In a few years, he was to write 20 of these dramas. Many were adaptations of literary works by others, but he scored his greatest success in the medium with an original fantasy, Visit to a Small Planet. He adapted Visit to a Small Planet for the Broadway stage, where it was an immediate hit. Touring companies crisscrossed the country for many years.

Television dramatists like Vidal, Paddy Chayefsky and Rod Serling were public figures in the 1950s, and Vidal was asked to appear on the new talk programs like Today and The Tonight Show. His mellifluous voice, ready wit, gift for mimicry, and unexpected candor about sex, politics and every other subject made him a sought-after guest. He was also called on to edit anthologies of television drama and to lecture on the new medium.

Film adaptations of Visit to a Small Planet, and Vidal’s Billy the Kid drama, Left-Handed Gun, were disappointments to him. He accepted an offer from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, eager to see firsthand how films were made, and to observe the last days of the old studio system. He was one of the last writers to be placed under long-term contract to any studio.

Vidal prospered in Hollywood, writing acclaimed screenplays for The Catered Affair (based on a play by his television colleague Paddy Chayefsky), Suddenly Last Summer (based on a play by his friend Tennessee Williams) and J’Accuse, based on the famous Dreyfus case of official anti-Semitism in France at the beginning of the 20th century. He also worked as an uncredited script doctor on the epic film Ben Hur, in exchange for which he was released from his contract. His earnings from television, Broadway and Hollywood had now freed him to write what he pleased without taking on other work. But just as he was prepared to plunge full-time into literary labor, ghosts of his Washington past returned to draw him back into the world of electoral politics.

When his mother divorced Hugh D. Auchincloss in the 1940s, Auchincloss married Janet Lee Bouvier, whose daughter Jacqueline moved into Gore Vidal’s old room at Merrywood. By 1960, Jacqueline Bouvier was married to Massachusetts Senator John F. Kennedy, then preparing a run for the presidency. Kennedy was eager to meet his wife’s famous literary connection, and Vidal became fascinated once again with the machinations of political life. He wrote a play, The Best Man, exposing the backstage intrigues at a presidential nominating convention. The play was a hit on Broadway, and was later made into a successful motion picture, the only film version of his work with which Vidal was entirely satisfied.

Meanwhile, Vidal had become friends with a Dutchess County neighbor, Eleanor Roosevelt, widow of the 32nd president. With the encouragement of the Kennedys and the Roosevelts, Vidal decided to challenge the incumbent congressman from Dutchess County, a strongly Republican area. One of the only Democrats ever to have won election in the area was Franklin D. Roosevelt himself, elected to the State Senate in 1910. The odds were formidable, but Vidal exceeded expectations. Although he lost the general election, he garnered more votes in the district than Kennedy, the party’s presidential candidate.

For the first year of Kennedy’s presidency, Vidal enjoyed the role of intimate to the first family, but he soon felt confined by the atmosphere of official Washington and was eager to return to literary work. He moved to Italy and began work on the novel Julian, about the fourth century Roman Emperor who attempted to turn the Empire away from its official Christianity and back to the ancient traditions of Greek philosophy. The book was published to great acclaim and topped the bestseller lists in 1964. After Julian, Vidal made his living as a novelist, turning to the essay or the lecture stage only to express his passionately held opinions on literature and politics.

In the 1967 novel Washington, D.C., Vidal revisited his native city, following a set of invented characters through the changing political atmosphere of the city from the New Deal to the Cold War. The following year, Vidal outraged a few and amused many with an offbeat satirical novel, Myra Breckenridge. Written in a wildly original style, the book combined themes of the movie business, transsexuality, drugs and religion. It was later made into a film he described as the worst movie ever made.

Gore Vidal enjoyed shifting back and forth among a number of favorite genres of fiction. He returned to his fictional chronicle of American history with the 1973 novel Burr, which many consider his masterpiece. He tells his story from the point of view of a young journalist in 1830s New York who makes the acquaintance of the elderly Aaron Burr, last surviving member of the Revolutionary generation of 1776. The real-life Burr shot and killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel while serving as Vice President, and was later tried for treason after being accused of a plot to break up the United States. In the novel, Vidal fabricates a memoir by Burr himself, transmitted to the young journalist. Vidal’s journalist hero reappears in a subsequent novel, 1876, set against the backdrop of the disputed presidential election of the nation’s centennial year. Vidal continued this “American Chronicle” with Lincoln, Empire, Hollywood and The Golden Age, following several generations of related families through nearly two centuries of American history.

Between these massive works, he continued to explore his original brand of satire with works like Duluth, The Smithsonian Institution and Live from Golgotha. He explored the world of the fifth century, BC, with Creation, a tale that follows its protagonist from Persia to Athens to India and China, and touches on the origins of some of the world’s major religions.

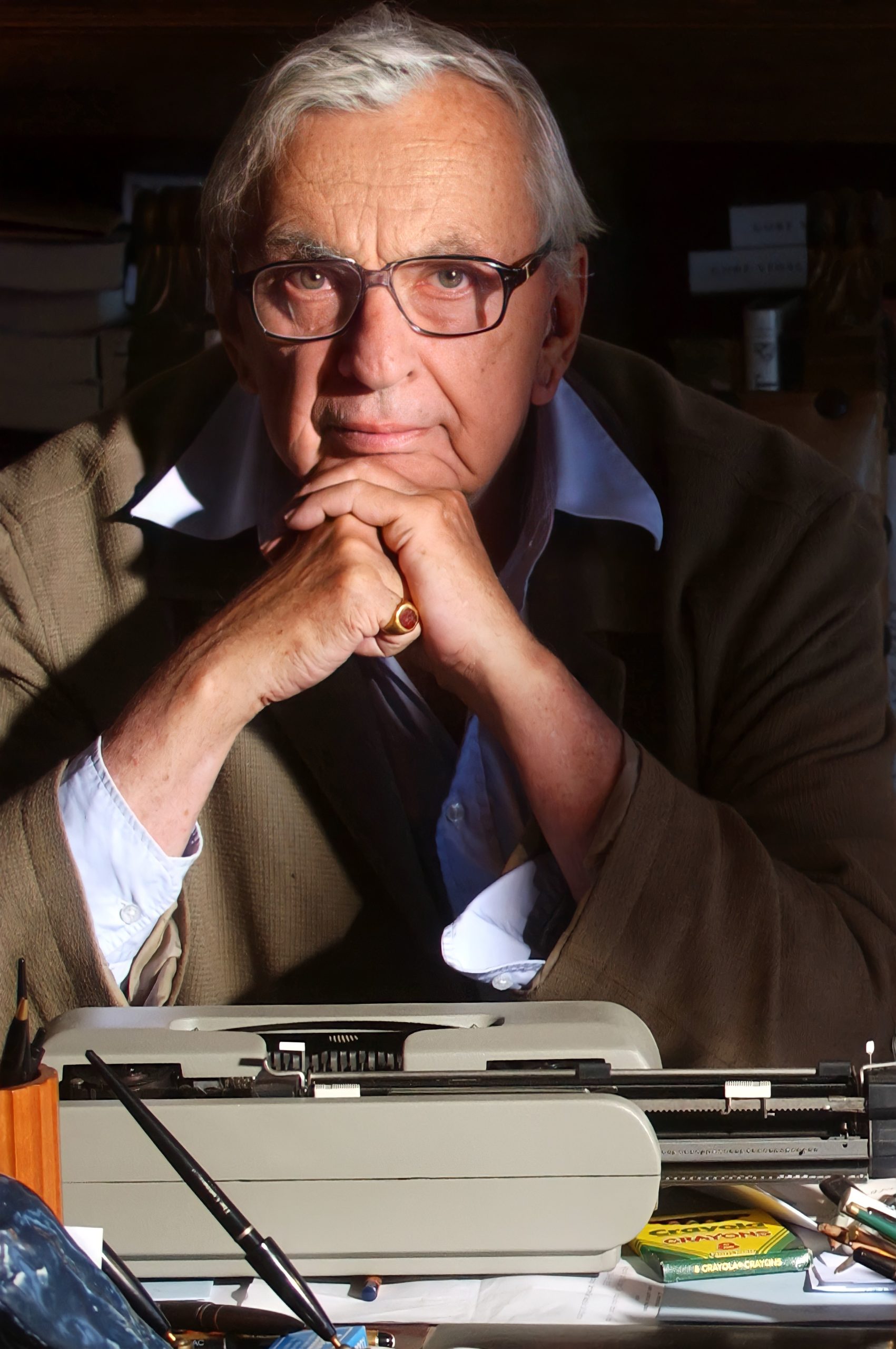

Beginning in the 1950s, Vidal published occasional essays on politics and literature. In later years, these most often appeared in The New York Review of Books. These essays were gathered each decade in bestselling collections like Rocking the Boat, Sex Death and Money, Homage to Daniel Shays, Matters of Fact and Fiction and At Home. A collection of 40 years of his work in the essay medium, United States: Collected Essays 1952-1992, won the National Book Award in 1993. The award confirmed Vidal’s status as the greatest English language essayist of the 20th century.

From his opposition to the Vietnam War in the 1960s to his opposition to the Iraq war in the 21st century, Vidal was one of his country’s most outspoken social critics. During the Vietnam War, he helped found the short-lived People’s Party, a revival of the 19th century Populist movement in which his grandfather had been a young leader. In 1972, the People’s Party nominated Dr. Benjamin Spock for President. Spock promised that, if elected, he would appoint Vidal Secretary of State. Vidal made a more serious foray into electoral politics in 1982, when he ran for the United States Senate in California, where he had long maintained a home. He was defeated in the Democratic primary by then-Governor Jerry Brown, who lost to San Diego Mayor Pete Wilson in the general election.

From the 1960s, Vidal kept an apartment in Rome and a villa in Ravello on the Amalfi Coast. At the same time, he maintained a home in the Hollywood Hills and made occasional appearances as an actor in films such as Bob Roberts, With Honors and the television movie Billy the Kid. When his longtime companion Howard Austen fell ill in 2003, he gave up the home in Italy and returned to Los Angeles for good. Austen subsequently died that year.

In his later years, Vidal gave up writing longer novels, and published two volumes of memoirs, Palimpsest (1995) and Point to Point Navigation (2006). He also published a thoughtful study of the Founding Fathers, Inventing a Nation: Washington, Adams, Jefferson (2003). He continued to publish book-length essays on political topics, such as Dreaming War and Imperial America. Until his final illness, he continued to speak publicly against what he saw as the erosion of constitutional liberty in America. He died at home in Los Angeles at the age of 86.

Gore Vidal wrote his first novel at age 19, while serving in the United States Army, and was acclaimed as one of the most promising young writers to emerge from World War II. He created an international sensation in the late ’40s with The City and the Pillar, a novel that shattered the taboo barring frank portrayal of sexuality in American literature. In the 1950s, Vidal pioneered original drama on television, and enjoyed smash hits on Broadway with Visit to a Small Planet and the political drama The Best Man.

Vidal’s essays and television appearances established him as a formidable political commentator and social critic. He was in constant demand as a public speaker, renowned for his wicked wit, dazzling erudition and sincere outrage at the corruption of the political process.

Over the decades, he thrilled readers with international best-sellers in an astounding variety of styles, from philosophical dramas of classical antiquity like Julian and Creation, to hallucinatory satires like Myra Breckinridge and Duluth. His crowning achievement may have been his masterful recreation of American history in a series of novels including Burr, 1876 and Lincoln. His collected essays, United States, won the National Book Award in 1993. Critics debate which of these works is his finest, but his cumulative achievement made Gore Vidal the greatest American man of letters of his era.

When did you start writing? When did you discover you had an aptitude or a desire to write?

Gore Vidal: The first time I read my first book all by myself without my grandmother helping me. She was my reader for a while. As soon as I started to read and understand it easily, I started to write a book. I thought, “This is not only easy to do, but I think I could probably do it better than they’re doing it.” At least I would write something more to my own interests.

How old were you?

Gore Vidal: Nine.

What is the first thing you wrote about?

Gore Vidal: I had seen a movie called The Mystery of the Blue Room, I think it was called. I can’t find it in any of the encyclopedias, but I remember liking it very much, and so I wrote “The Mystery of the Blue Room.” Yes, I was a plagiarist very early, just borrowed it from the movie. Nobody noticed. Nobody had seen it in my family. There I was, retelling the story, but I was using family characters, my grandmother, who was a wonderful woman, very, very intelligent, but she never listened to anybody. She wasn’t deaf, she just didn’t like listening to people. She didn’t like talking that much either. She would occasionally say something intelligent, but she would miss an entire conversation because she’d be thinking about other things. And then she would ask the subject of what we were talking about. We said, “But we told you a few minutes ago.” “Oh, is that what it’s about?” And she would just drift off. So I was already using other people’s characteristics to decorate my tales.

We’ve read that when you were at Phillips Exeter, you joined America First.

Gore Vidal: I was the head of it.

Isolationist that you were, you went off and enlisted in the United States Army.

Gore Vidal: That’s what we did in those days.

At 17, I enlisted in the Army, and I served three years in the Pacific. I was the First Mate of an Army ship in the Aleutians, which is why I am in a wheelchair. Due to hypothermia, I had a frozen knee, which developed rheumatoid arthritis. Misdiagnosis naturally, by the Army. It turned out to be osteoarthrosis, and I now have an artificial knee. But the knees are the only part of the anatomy I have never had to use in life.

So you were still in the Army when you wrote your first novel?

Gore Vidal: I wrote my first novel while in the Army Hospital at Anchorage, Alaska, and then over here in Van Nuys at Birmingham General Hospital.

What inspired that?

Gore Vidal: Well, it was about a first mate on an Army ship in the Aleutian Islands. I think I was already working pretty close to home. I didn’t have anything else to write about.

Had you already decided that this was your life’s calling?

Gore Vidal: I think pretty much, although I decided I wanted to go into politics, but I didn’t know to what extent I would be able to get around physically, and you sit still when you write a novel, so I wrote my first novel there, sent it to a publisher. I wrote it at 19; it was published when I was 20.

It got good reviews, didn’t it?

Gore Vidal: Yes indeed, followed by very bad reviews for The City and the Pillar, my third book.

You got bad reviews for The City and the Pillar after the good reviews for your first book. Why was that?

Gore Vidal: It was a book about the absolute normality of “same-sexuality,” as it was sometimes called. Remember, I spent all my life not only in boys’ schools, but here I am stuck in three years of the Army. I knew exactly what went on in the real world. It was Walt Whitman who said, “No one will ever know what goes on in armies.” Everybody thought it was the bloodshed and so on. Whitman was after different game. I knew what went on in the real world, and I thought, well, nobody would write about it.

Certainly not in America, up to that point.

Gore Vidal: No, certainly not in a favorable way, although I am pretty nonjudicial.

All the people who had praised my war novel were suddenly hysterical over this book, and I responded in kind, being brought up by the Gores, sharp-tongued and quite mean-minded as I get angry, and I am quite for fighting back. I have conducted an absolute feud with The New York Times for 50 years, because of what they did to that book and to me. They’re not doing very well these days, I’m happy to report from the front.

You must have known that you were inviting controversy, if not worse.

Gore Vidal: Well no, I’m not exactly stupid, but at the same time, I didn’t realize how stupid they were.

You were writing a serious literary work on a subject that hadn’t been touched on before.

Gore Vidal: Well, it had been touched on before. After all, there was Proust. All sorts of great writers had dealt with it, but always in a peripheral way. All you have to do is spend three years in the Army. There is nothing you don’t learn about that subject, among other things. It seemed to me something that needed doing.

I suspect at a very early age that one of the things I most disliked in the world was: a) dishonesty, and hypocrisy. Since the United States is firmly based on both, I had a rich subject, my native land, and certain taboo subjects were obviously going to interest me. Why, of all the founding fathers, did I pick Aaron Burr to write a book about? Well, I thought it was time that his point of view was expressed, because he is very interesting about the founding of the country.

How did that affect your career as a young novelist?

Gore Vidal: It was not a brilliant move, no, but I attracted a large audience in many countries aside from the U.S., and then I went to television to make a living. The New York Times didn’t care what was on television. I finally came back to the novel, with Julian, and I have been a novelist ever since.

You mentioned going into television to make a living, which raises a point. What does a novelist have to do to survive in this world?

Gore Vidal: You write plays for live television, if there is such a thing. It had just come into being in the early ’50s.

I wrote a play for something called Studio One, which was CBS. That did well, and then, I wrote 20 more plays. Hollywood beckoned. I was the last contract writer at MGM. I didn’t need the money by then, I was just doing it to see what a great studio was like, because I knew the studio system was about to vanish from the earth. It’s like observing the troglodytes at home, and it was fascinating. By then I was on Broadway with plays. I’ve supported myself by writing all my life.