What is music? Well, it’s this: it's an expression of art, of humanity, of humankind doing this. No...this is something important for the health of the spirit of the people.

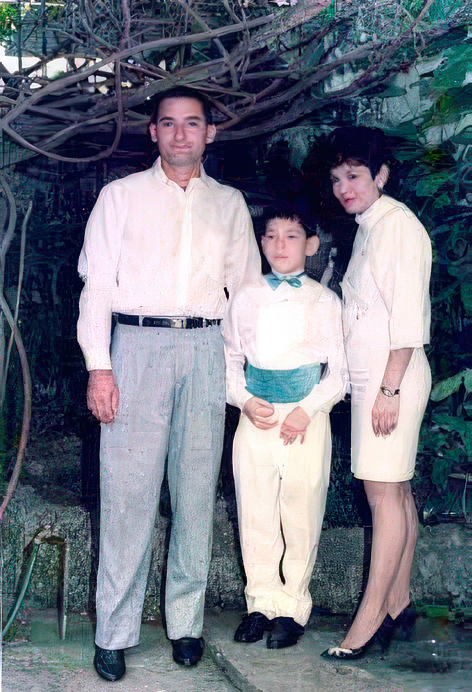

When Gustavo Dudamel was a small child growing up in an industrial city in Venezuela, still too small to hold his father’s trombone, he taught himself to conduct an orchestra by following along with recordings of symphonies, using his action figures to stand in for the musicians. An unusually imaginative and determined child, there were signs from the beginning that he might grow up to become one of Venezuela’s greatest music-makers.

Gustavo’s young parents made a modest living as musicians – his father was a salsa trombonist, and his mother taught singing – and though Gustavo learned theory from an extremely early age, they couldn’t afford to buy him an instrument.

Dudamel is now one of the most recognized conductors in the world, a winner of seven Grammys for his classical recordings. In 2026, he will begin as musical director of the New York Philharmonic after 17 years at the Los Angeles Philharmonic, where he’s become a celebrity and peerless popularizer of classical music. Dudamel believes “music is for the health of the spirit of the people, not a technical thing.”

Dudamel was born in 1981 in Barquisimeto, Venezuela, a large city with a strong musical culture, both of European classical music and local Venezuelan folk traditions. He longed for the chance to play an instrument himself. and got the chance before the age of 10 when he joined El Sistema, a public music education program for underprivileged youth newly founded by the Venezuelan conductor and economist José Antonio Abreu. He took quickly to the violin, but still dreamed of leading the entire ensemble. By the time he was 11, Dudamel’s talent was recognized by the conductor of the children’s orchestra in which he played, and he was brought on as an apprentice.

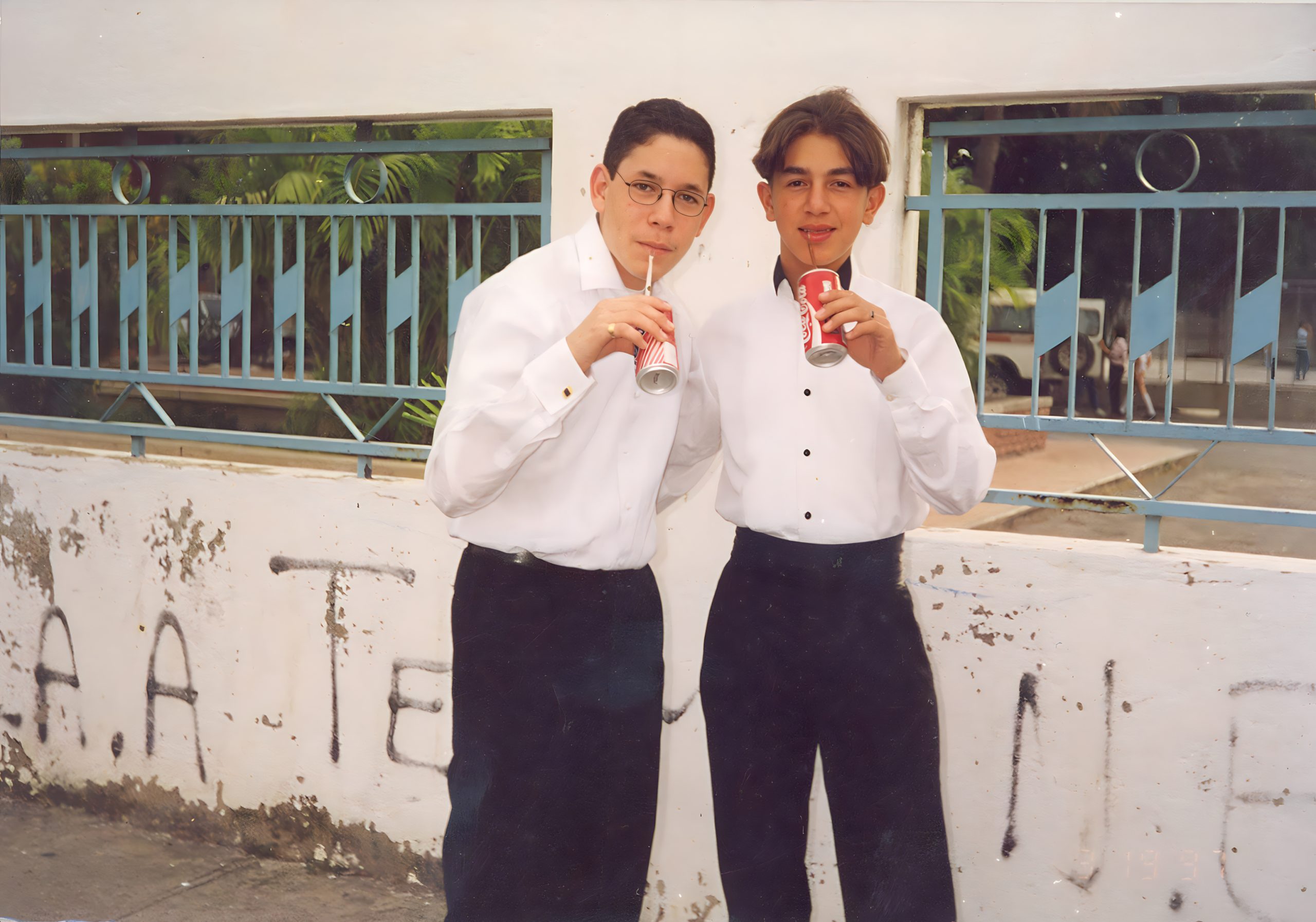

At 15, Dudamel was conducting the Simón Bolívar Youth Orchestra in Barquisimeto and studying privately with Abreu. In 1999, at 18, Dudamel was named music director not only of SBYO but all of El Sistema, a program that’s served hundreds of thousands of students from all over the country. The next year, he accompanied the SBYO on a tour of Germany, culminating in a performance at the Berlin Philharmonie. At age 20, he was invited back to study conducting under its director, Sir Isaac Rattle.

Dudamel’s fame was growing, and increasingly known in the music world for his rare combination of natural talent and tireless dedication to his work. He would travel back and forth from Venezuela to Germany for several years, perfecting his art. His break came in 2004, when Abreu pushed him to enter the first ever Mahler Conducting Competition in Bamberg, now one of the most prestigious in the world.

The twenty-three-year-old Dudamel emerged as the clear victor, surprising a musical establishment expecting someone much older. Critics at the time pointed to his unlikely combination of youth and experience, and it became obvious that the conductor was destined for great things. Offers began pouring in, and in 2005, at age 24, he performed with several major European orchestras, as well as the Israel Philharmonic. In September of that year, Dudamel was invited to conduct at the Hollywood Bowl, his American debut. The performance was a stunning success and put him on the radar of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, which had established a tradition of hiring young prodigies as its music directors.

In 2006, Dudamel released his first album with Deutsche Grammophon, Beethoven, Symphonies Nos. 5 & 7, establishing himself as an authoritative voice with classical music’s premier record label. That same year, Dudamel was named music director of Gothenburg Symphony, where he would work for the next six years while also conducting other orchestras across Europe and the United States. In 2007, still riding the success of his Hollywood Bowl debut, he was selected to be the music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, an appointment that would start in 2009. He was only 26 at the time of the announcement.

Soon after signing on with the LA Phil, he helped found YOLA (Youth Orchestra Los Angeles), a program inspired by El Sistema to help at-risk children through intensive, daily, communal music training for free. The Los Angeles youth program now has over 600 students. With the help of a donation by Judith and Thomas L. Beckmen, they practice in a music hall designed by Frank Gehry.

Music has been a means of social change for Dudamel since the beginning of his career. He describes art as an “existential” thing that children must not be deprived of. When they are, he says, it opens them up to other, negative demands on their attention that he knows all too well: El Sistema kept Dudamel’s classmates in Barquisimeto from getting involved in drugs and crime. Children learn “how to build a life,” he says, from the structure of an orchestra and music itself. Besides YOLA, he’s helped establish El Sistema-type initiatives for underprivileged youth in Sweden and Scotland. In 2012, he established the Dudamel Foundation, a charitable organization that works to expand access to music, which it sees as a human right and a basis for a harmonious society. With his wife, the actress María Valverde, Dudamel has extended the Foundation’s impact across multiple continents.

Leading the LA Philharmonic, Dudamel’s charisma, enthusiasm, and sense for what was truly exciting in classical music made him first a crowd favorite, then a celebrity musician outright. Orchestras under his direction play as they never have before, but it’s also Dudamel himself who draws the crowds: with his wild “conductor hair” flying and a smile on his face, he invites the spontaneous applause traditionally shunned in classical performance.

Dudamel wants people to think of classical music as something relevant to their own lives. He’s done that through unexpected appearances on Sesame Street and his 2016 appearance with Coldplay, Bruno Mars, and Beyoncé at the Super Bowl Halftime Show. In 2018, Katy Perry performed alongside him at the LA Philharmonic’s centennial concert. He also conducted the orchestra in the soundtrack of Star Wars VII: The Force Awakens (2015) and Steven Spielberg’s remake of West Side Story (2021), the latter of which won him a Grammy. The character of Rodrigo, the charismatic savant conductor in the hit Amazon series Mozart in the Jungle, is based on Dudamel, who also has cameo appearances in the show.

Dudamel’s free, dynamic relationship with music is in line with the view he’s inherited from El Sistema: art is a living thing that can achieve social good. At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, he and the LA Philharmonic worked to bring free virtual performances to an isolated and dispirited world. In 2022, he staged a production of Fidelio, Beethoven’s only opera, which the deaf composer had written after he’d already begun to lose his hearing himself. Dudamel’s rendition featured a deaf chorus, including members of El Sistema, signing in visual accompaniment with the original, audible score.

Dudamel has collaborated with several of the greatest living composers and helped popularize their work. With John Adams, he conducted his acclaimed opera, The Gospel According to the Other Mary, and his piano concerto, Must the Devil Have All the Good Tunes?

Dudamel’s relationship with his native country has been fraught. El Sistema and the Simón Bolívar Orchestra operate under the office of the president, Nicolás Maduro, whom democratic leaders around the world have heavily criticized for his human rights abuses and repression of political enemies. In 2017, after enduring years of criticism for not speaking out against Maduro, Dudamel publicly denounced the regime for its brutality. A young El Sistema violist had just been among a group of protesters killed. Maduro then rebuked Dudamel, cancelled his tours with the Simón Bolívar Orchestra, and declared him persona non grata.

Dudamel no longer considers himself a “young conductor,” but believes “there’s still a lot to discover” in classical music. Having revolutionized classical music, he’s now positioned to bring up a new generation of artists and maybe to discover the next youthful genius.

Since his youth, Gustavo Dudamel has been remaking the world of classical music from the bottom up, reinvigorating the genre and opening audiences and orchestras alike to new communities. Wielding extraordinary natural talent with an inspiring, generous warmth, he leads orchestras to play as no one has ever seen before. Beginning as the director of the Simón Bolívar Youth Orchestra in Venezuela at 18, he soon took major conducting competitions by storm and was conducting at venues like La Scala and The Hollywood Bowl. By 26, he was the musical director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

Dudamel established himself as one of the greats even before his hair began to gray, but his seven Grammys and innovative tenure at the LA Phil have proven that he’s more than a wunderkind. He’s earned renown for his leadership of El Sistema, a unique organization in Venezuela that provides social welfare for hundreds of thousands of children through free, intensive music education. Brought up in El Sistema himself, Dudamel has helped establish offshoot programs across the world.

Gustavo has injected new life into classical music and earned well-deserved celebrity in the process. His charisma, vivaciousness, and conviction in the importance of doing good have enchanted people around the world and made him a hero in his homeland.

The chemistry between the conductor and the orchestra

Gustavo Dudamel: You have to understand as a conductor that you are nothing without the musicians that you have in front. So, everything starts from admiration and respect. When you really put that first and then you put your knowledge about what you know and what you want to achieve, then it’s the right order of things. And it’s an opportunity. When you are in front of an orchestra is a gift. You know, it’s a gift to have the chance to guide these wonderful musicians that have played with the best conductors. They have developed their careers in the highest level. And you have the opportunity to be in front of them and inspire them. Because at the end the technical things, let’s say, are not difficult, when you have a professional orchestra in front, are not difficult to work with because the orchestras will do in one minute. But how to guide them in a journey of inspiration with music, not only would be charming or beautiful or moving, no, it’s something about that kind of mystery, this mysterious moment that we have every rehearsal and that it gets the real dimension during the performance. This is something that you, you have to know or you have to let this happen in the most natural way. When you force that, then it gets out of context. And I remember that first concert with, with the Philharmonic, with Los Angeles Philharmonic, it was very beautiful because I was at the Hollywood Bowl, and it was really beautiful like this, you know, beautiful with [unclear] and Tchaikovsky. But then my first subscription was that one also in America with the Philharmonic doing L’Atlantida, Bartók, and Rachmaninoff with Fima. And that was beautiful because we were in the right acoustics to work, to do it. And yes, it was a magical moment. I think that moment was kind of the moment that started the possibility for me to be music director there.

First memories of music

Gustavo Dudamel: Well, I think watching the pictures of my childhood, I think, I think it’s very far. I remember there are some pictures where it’s a little piano toy which I was playing, and all of that. There are pictures of my father playing the trombone in front of me, I was a baby just a few months old. But, you know, memory, memory, memory, I think is listening to my father studying, you know, the trombone and listening to him or studying solfège, for example. And I think that is my very first memory and my connection with music, yeah. My mother was more amateur, you know, and singing in a choir. So, it was a very musical family. I have an uncle that play a folk instrument like the cuatro and the harp, the Venezuelan harp. He was playing the piano also. But it was very musical. My grandmother also had a great voice and she loved to listen to music. So, I have a mix of, of music styles, you know during my childhood. And you know, I was listening to Beethoven, to all of this, but at the same time, I was listening to boleros, to all of these Latin music or folk music from Venezuela. So, yeah. But my mom also sings beautifully. It was very natural, the atmosphere, the musical atmosphere at my house at home, it was very mixed, because it was nothing like, “If you listen to Beethoven, you cannot listen to pop music or you cannot listen to rock or to Latin music.” No, it was kind of very natural. As my father was studying Mahler’s First Symphony, he was playing, you know, Héctor Lavoe salsa music, so Fania music. So, this was the big — I think it is a gift for me. It was a gift, you know, that I had that opportunity to be surrounded by all of that and not being, you know, pushed in only one way.

How did your parents meet?

Gustavo Dudamel: It’s very funny because my father, they were teenagers. They had me when they were very young. And they met because there is some music, typical music in Venezuela called gaita from Maracaibo. And my father was playing in a gaita group where my mother was singing, and it was a very amateur group. You know, all the teenagers from the neighborhood, they got together and they were playing at the square in front of the buildings, and they met in that way. My father was giving serenades to my mom with his friends, so they met through music. It’s beautiful, but it was music that made them, you know, connect.

Growing up in the music capital of Venezuela, Barquisimeto

Gustavo Dudamel: Barquisimeto is one of the principal cities in Venezuela, in the economy and all of this, I think it’s the third one. At that time, also, Barquisimeto, this is very important, it’s called the musical capital of Venezuela. And it was because they did a census, and when they did the census, they found that in each house, in each home, was a musical instrument. And of course, you know, it was very, it’s a very musical, musical city, state, not only Barquisimeto, but Lara, the state is very musical. You have many, many wonderful folk traditions which I grew up with. But at the same time, I grew up in a middle-class, poor neighborhood, you know, very, very beautiful. I don’t have any regret about my childhood because it was very beautiful. But at the same time that I was doing music and all of that, you know, there was surrounded drugs and all of these kind of things, you know that affect the community. And yes, for me music was a space to don’t be connected to that. And I have great friends, you know, when I was a child who — so they decide to go through the other, you know, path and it was — it’s sad, but also others, they did wonderful things in the sports, and the medical skills, and all of these of things. But yeah, it was a very — It have the complexity of a community that is surrounded by these difficult things for young people.

As a child, Dudamel learned about music through a publicly financed music education program founded by Venezuelan educator, musician, and activist José Antonio Abreu.

Gustavo Dudamel: Maestro Abreu was a visionary. And when you see, you know, the real power of art that is not only an entertainment element of society, if not a real transformative element of the community. That is what Maestro understood. I was not at the beginning of El Sistema. I was not born when he created. But Maestro Abreu had these few musicians in front of him that very first day, and the reason was that the young people of Venezuela didn’t have a space to do music. It was the first thing. It was a very good, beautiful national orchestra which was full of foreigners. And there were like one or two Venezuelans only in, like, in a group of 18 musicians. And it was not opportunities for them. So Maestro created that space for them. He had that first rehearsal. And it’s amazing because he said, there is a video of that rehearsal, he said, “We will multiply this. We will go to all the communities of Venezuela, and we will fill every, every little village with music, and you will be with me in this adventure of creating that.” It was 1975, you know, now more than a million of children, you know, this is something that — of somebody that really understand and give the real concept to something that we think is only one thing that represent only one thing.

What is music?

What is music? Well, it’s this. It’s an expression of art, of humanity, of humankind doing this—no, this is something important for the health of the spirit of the people, more than a technical thing, and this is El Sistema.

It started with an interest in the trombone

Gustavo Dudamel: You know, as a child you see this beautiful gold instrument, you know, in front of you that makes that beautiful and powerful sound. I was conquered by that. I wanted to play salsa like my father. You know? Classical music was, of course, the way to learn things, but I wanted to play in a salsa group like him. And yes, it’s still one of my favorite instruments. At that time, you know, Sistema was founded, it was maybe the second site of El Sistema created by Maestro Abreu was Barquisimeto because also he was from, he was studying in Barquisimeto music when he was, when he was a child. And of course, the Sistema was starting, we didn’t have many resources at that time, and we have only one trombone at home, and it was too big for me. It was impossible for me to play. And I try, you know, I wait. I study solfège for a long time. I study harmony. I study all of this theoretical musical things, you know. And then I was waiting, and I wanted to play an instrument. I was desperate. Because I knew it, the notes, I knew it, you know the technical things to build something, but you need to play an instrument. And of course, I was trying with the piano, but I wanted to play another instrument, and like, like the trombone. And I tried the trumpet for like three weeks or something like that. It didn’t work. And there was a violin and in the orchestra spanning, it’s funny, at the Sistema side, in Barquisimeto there were, there were more violins, so they gave me one violin, which I tried. And all my friends were playing violin, so it was, it was wonderful to be with them. And yeah, I changed to the violin because my arm was too short.

A passion for conducting is born

Gustavo Dudamel: The conducting thing started really early and it was because I went to a concert that my father was playing with the orchestra, the Barquisimeto Orchestra. And I was amazed, it was very beautiful. I think it was Scheherazade by Rimsky-Korsakov, and I was listening to that, that I saw that theater in the middle moving the hands, it was a very, very emotional conductor, very expressive. Which for me was like, wow, what is this? And I started to try to discover that. And the first thing was like with the recordings at home I was conducting. And then my grandmother gave me a baton, I remember. And I was conducting at home, and it got very serious, you know, it was, of course I was playing, but it got very serious because I was rehearsing. I was preparing the orchestra with no knowledge of what was that, you know, it was only instinct that I was saying like, “Let’s balance this. Let’s do this.” With the recordings, that is why I said, I say always, I was conducting all of these big orchestras since I was 6-7 years old.

Gustavo Dudamel: I have some little toys. They were not soldiers. They were like this Fisher Price toys, you know, little persons that they have, and I remember it was a gas station. They gave me this gas station and they have these, have like five of these little people there. And then it was another game that I have that have other little ones and then I placed them like an orchestra. It was very serious, you know, it was kind of very organized and what I was doing, I was doing my concerts. I prepared all of that. And of course, that moment, I think it was 1992 when I was in the orchestra and the conductor was late, and I jump in the podium because it was a little bit of, you know, crazy atmosphere, and I went and I started to imitate the conductors.

Gustavo Dudamel: Yeah, I think I was 11 years old.

Gustavo Dudamel: At the beginning, we laugh, you know, because you know we were, we were making fun of the conductor in a way. But you know, in a moment, in a moment, you know, I saw Carrion’s videos that time. They were showing that at the conservatory, and he was conducting with his eyes closed all the time. So I was trying to — and then suddenly everything started to be very calm and people following and all of that. And I say, “Wow, what a power, a power I have,” you know that — And then I opened my eyes and then it was the conductor in the back of the orchestra, I said like, just, “This is the end in my musical career because he will, he will kill me, you know, because I’m imitating him, doing all of these funny things.” But he was kind of. I think he was surprised. I was, you know, I was playing violin. I was one of the first violins. I was concertmaster in the orchestra in this children’s youth orchestra. And he, he said, “No, no, no. Keep doing what you are doing, but you rehearse.” And I started to rehearse. He was sitting there. The orchestra was kind of surprised too, because they didn’t know how to behave to that. And it got natural. I left the podium. I remember we finished the first part of the rehearsal, and he told me, “You are now my assistant.” And I got my first job as an assistant conductor.

A spiritual experience

Gustavo Dudamel: I will say it’s very in a way looks very physical. You know, it’s like a dance. At the end, you are moving your hands in front of an orchestra, your arms, but it’s like a choreography, and that is, that is a dance part of, of conducting. But I remember, I didn’t have any kind of, at that time, you know, in the 80s, I didn’t have videos of what was a conductor. I only went to a concert and I saw and I was trying to imagine what I was studying and analyzing and trying to move my hands and do something with that. But at the end, yes, is something that starts from that, but then it gets very deep in a very, I will say philosophical, metaphysical, psychological thing, conducting—more than. Spiritual. It’s more than moving your hands in front of an orchestra and the people watching you jump or move or do these kind of things, it’s something very spiritual, that is right. Yeah.

Learning from great conductors

Gustavo Dudamel: Giulini, which was a very, I consider him a very spiritual conductor. You know? It’s true that he didn’t have a gesture, let’s say a beautiful gesture to show to the orchestra, but it’s something more than that. And I remember Lorin Maazel, which was a very important figure, because for me, he have an amazing technique in conducting, you know, this clean, beautiful, clear, powerful, all of that. And he told me, you know, there are conductors and there are natural conductors, and this is something that I will say, it is something very natural in your spirit if you know how to open that door, you know, and you have the chance, the opportunity to evolve in that space of understanding the real dimension. The real dimension is very big. It’s not only one dimension. All of this dimension that you have the opportunity to discover, this is, I think this is the secret of conducting, you know, more than knowing historically what you are conducting, more than knowing your technical things that you can tell to the orchestra. There is something that goes beyond that and it’s that, that unique connection that we can describe, you know, as spiritual, as metaphysical, as psychological, but it’s something that, that is the most wonderful thing that I think conducting, you know, the conducting life, half, you know, is this kind of understanding that that dimension that goes even beyond the notes that you are conducting. And, you know, I’m in this path, you know. I’m not anymore a young promise or a young conductor, I’m middle age already, but I consider that, you know, there’s a lot still to discover. And it’s amazing when you open that door and you have the chance to develop that understanding of what is conducting about.

In 2004, Dudamel entered the Mahler Competition which would change the course of his career.

Gustavo Dudamel: This is also very, very funny because Maestro Abreu was the one that told me, you know, “Here is the application,” he filled for me the application and he said, “You are going to this competition.” You know? He was very — He never pushed me to do things, you know? He always pushed me to have discipline and to study and to think more, you know, always, even if I knew that something, he made me question to really go deeply, and in the understanding, not only music, you know, in life, in many things that we have every day in our lives. He was like a maestro of life, not only of music, and it was amazing. And I went to Berlin for like three months to be with Simon, rather I saw, I remember I think, “Ozawa, Barenboim, all of these great conductors. It was beautiful to sit in that hall and have this privilege to listen to and to watch and to learn, because it’s true you learn a lot watching others do the rehearsal, mostly rehearsals, than concerts. And I remember my maestro told me, Look, you have to be very smart,” he said. “You will learn many things that are good, but also you, if you are smart enough, you will learn things that you don’t have to do.”

You know, he was kind of, you have to understand that, that balance of things. So, I was kind of watching. So, I learned many things, many wonderful things, very positive. And I went back to Venezuela. And the competition was one week after. And I didn’t want to go to Bamberg, you know, I was three months in between Berlin and Salzburg, and then I went back. I have my friends. I wanted to stay there. And I started said to maestro, “Look, maestro, I have a pain here.” “Don’t worry. I have this medicine for you.” “I have a pain here.” “No, no, no. I have this. You have to go.” So, I went. And I arrived to this beautiful, beautiful, beautiful city, Bamberg is very, very — You walk. I remember the hotel was next to the hall. You walked through the river. It was very small, very, very beautiful. And I said, “Look, let’s do it.” You know, Simon told me, “No, you don’t need a competition. You have only to develop this and all of that.” So, I went to the competition, and I encountered these wonderful conductors which, you know, they were so smart. They were speaking English perfectly, in German, and all of that. I was like, “My God, what the hell I’m doing here?” You know, this is kind of — I don’t belong to this group. I respect all of this, but I’m not, I’m not [unclear]. I passed the first round. I was expecting for me to go back to Venezuela faster, but then I passed the first round, OK. I passed the second round. It was getting like OK, maybe I have to keep going here. So, and at the end, I arrived to the finalists and I won. And this was a moment, you know, where I understood. Because my goal was not to go out and conduct orchestras around the world, my goal was and still is to do music with my friends. You know, that is why I wanted to go back to Caracas and to Barquisimeto and to Venezuela, and to be with, with, with my people. But that was a door that opens, you know, many possibilities. And yes, the Bamberg competition was a very special moment. And look, I got this invitation to Los Angeles. From the moment of the final I remember, it was like that and look where, where we are now, you know, it’s 20 years of a beautiful relation.

In 2007, the LA Philharmonic signed Dudamel for the 2009-10 season. That year, inspired by El Sistema and Dudamel’s life story, the LA Philharmonic, led by CEO Deborah Borda, founded Youth Orchestra Los Angeles (YOLA)

Gustavo Dudamel: I’m very grateful to the Philharmonic and to all the community in Los Angeles that we had the opportunity to develop in our own, you know, with our own needs because El Sistema, of course you can take and you can replicate here and there, but it depends because every society, every community, have their own needs. And when we started YOLA, I remember it was one of the first things that was very important for me. And I think for Deborah, it was also something very important to bring joy and to create a program that connect the orchestra with the community, you know, and that gives, you know, the space for young people, especially to underserved children, you know, poverty and difficult conditions to have that space for music. And to see the evolution of YOLA after now 15 years is very important. Maestro Abreu always said something very, very beautiful. He said, “The culture for poor people cannot be a poor culture.” You know, and he said in the sense that for the poor people, for the people that needs, we have to give the best, the best that we can. We cannot be something like, OK, I will help you. And this is something that happened in Los Angeles. Now we have a center, you know, that dignify the work of these young people. You know, a beautiful, you know, building design by Frank Gehry, with the generosity of Tom and Judith and all the Los Angeles Philharmonic Board and Orchestra and community, so we have a space where you can build your dreams in the best conditions. This is justice. This is not only creating a beautiful musical school. No, no, no. Just this is a space for really have, you know, the best values in a space that have brings you, you know, the right aim, the right space to develop that. And this is something that makes me very, very happy and proud of this work.