You mentioned having a reputation for getting people their money back. We’ve read that you asked your first investors for very small amounts, $500 or $1,000 each.

Harold Prince: Oh yeah. We had dressers put up $500. We had 175 investors put up $250,000. They stayed with me, those 175 investors, for most of my producing career, when I was producing and directing my own shows, which is something Abbott had done. I directed and produced the shows, as in Cabaret. The point is that they didn’t need us on Broadway. They had Rodgers and Hammerstein doing just fine, and Feuer and Martin doing just fine and Leland Hayward and the Theater Guild. They didn’t need us. So when we decided to do the first show, we had to analyze what can we do that will impress people immediately that there are new boys in town and that we found a different way to invent the wheel. And we figured that the way to do that was to do a show as elegantly as it required, but cheaper in terms of cost than anybody was doing them, and get the money back to the investors as soon as possible.

The day after Pajama Game opened, the investors opened their mail and found a check for 10 percent of their investment, along with a great review in the newspaper. It takes a lot of smugness, I guess, or chutzpah, to know what’s going to happen at the box office, but we were pretty sure, and we did it. We did it again on the next show, and we just kept doing it for a while. Pajama Game cost around $69,000. Damn Yankees cost $162,000, and the investors got paid after 10 or 12 weeks. They were in the profits right away, so not only were they thrilled with the hits, they were thrilled with the return they were making on their money.

I think it’s very important in the commercial theater to return the investment. I know there are fewer and fewer people who agree with me, because the investor now is so wealthy in his own right that he’s the producer. So you look at a Broadway show today, and you will see a whole lot of names over the title, and really who they are is the people who put up the money to put the show on. They can take a loss if it doesn’t happen, and it’s a shot at a Tony Award and all that sort of thing. They enjoy the theater, but it isn’t the safeguard that I think… It doesn’t restrain you, the way it did us, to have to make it a good investment. Let’s see if I can make sense out of this. After a bunch of successes at the box office, it gave us the right to have failures that did something we divined was important for the musical theater form. In other words, you could say to the investor — and I would do it in a letter — “I am not certain you’ll ever see this money again, but you’ve been doing just fine,” and then we’d do Follies or Pacific Overtures. You’d do a show that you had to do for artistic reasons, that in fact, ultimately, in the case of both of those shows, are somewhat historical, but they never returned a plug nickel to anybody. But the investors didn’t care, because they took pride in being part of the process.

These days, it wouldn’t be enough to raise $169,000. What would you need? 10 million?

Harold Prince: Ten million doesn’t buy you much anymore. It seems to be going up. I heard about a show that just opened in London that cost 24 million or something. That ‘s a lot of scenery!

It’s not about art then, is it?

Harold Prince: It can be. You can create something artistic. The problem is, because of the escalating cost, do you want to? Or are you caving in to the audience?

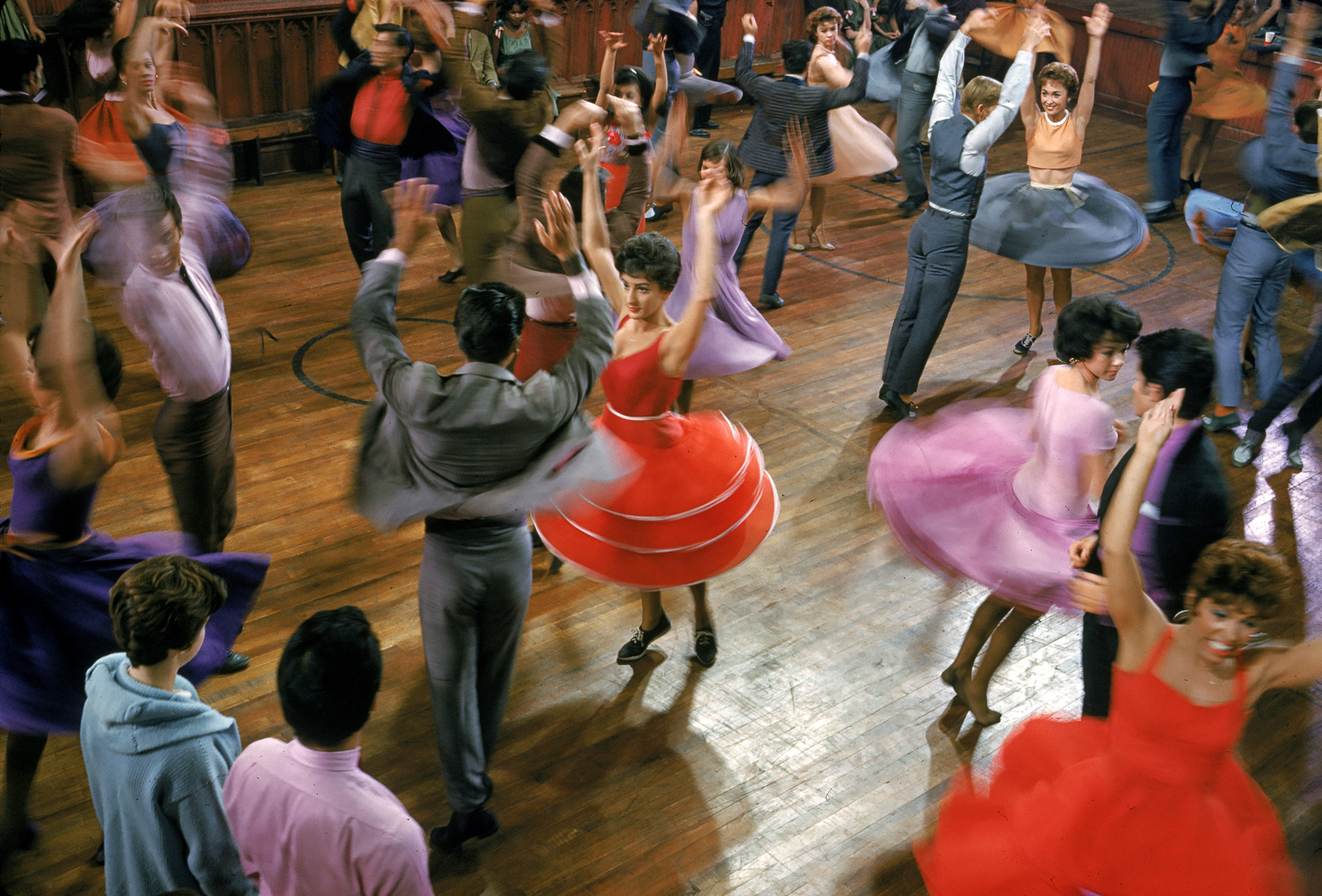

There is one definitive moment in the road. It is the moment when you as a producer, or even a director, decide that you are giving the audience what it wants rather than taking the audience on a journey you wanted to take. West Side Story is a perfect example of taking the audience somewhere. When it first opened, 100 people walked out on that show every night for a year. Lots of people didn’t get it. It didn’t win the Tony Awards or any of that stuff, but here it is, and it did pay off, and it made a film that they benefited from. The point is, I still believe you have to take your audience somewhere, and don’t underestimate how damn smart they are and how willing to be stimulated. But the situation was parlous at the moment.

It’s a different world now, isn’t it?

Harold Prince: Yeah, it’s a different world, but it’s not just the theater. It’s the whole entertainment industry. All of this reality television, and the business of being copycats all the time, that was something you didn’t want to do. You didn’t want to copy anybody. You wanted to be the first to do something. I think Fiddler on the Roof is the other show that would never have happened today. A lot of it was written, and its producer couldn’t raise the money and lost faith in the possibility that he ever would, and I grabbed it.

My partner had died by then, and I was alone and fearful. I wasn’t sure. You know, we’d had three partners, then two, then me. He died of a heart attack on the golf course. I had already done a couple of shows that succeeded after he died. So I had some credibility, and my office was on its feet again. Fiddler on the Roof, they asked me to direct, Bock and Harnick, and I said, “Though I’m Jewish, that’s not my family background, so I don’t know it. Mine is German. I don’t understand shtetls.” Sheldon Harnick gave me a book about shtetls, and I thought, ‘I’d be fraudulent, I don’t feel this.” So I said, “Get Jerry Robbins,” and he wasn’t available, and I said, “Instead, I’ll do your other musical,” which was She Loves Me, which was a great start for me in terms of people knowing I knew what I was doing, and a musical I loved. Then they went back to Jerry, and Jerry said, “Get Hal Prince to produce it.” So I said yes, and that seemed the perfect combination. Indeed, for Jerry, it was a hymn to his father. He did it for his father, and his initial dance teacher played the old rabbi in the original production of Fiddler on the Roof.

Looking back, it sounds like a fairly unlikely subject for a Broadway musical, life in the shtetl.

Harold Prince: It is. Jerry insisted and insisted and insisted on that opening number being larger, and engulfing a huge audience that wasn’t Jewish, that didn’t know about shtetls and so on. And over and over again, they’d talk about it, and then finally, one day somebody used the word “tradition,” and he said, “That’s it! Write about tradition. That, everybody has.” So the show has been as great a success in Tokyo as it was on Broadway and anywhere there is tradition. Well, where isn’t there tradition? Actually, unfortunately, there is less tradition today — and that is a terrible loss culturally to all of us — than there used to be, but that time, tradition was just international. Every country held on to that tradition, and the show succeeded because of it.

Let’s go back to the beginning of your career. You have said that your parents took you to the theater a lot as a kid. Do you remember a time when you weren’t interested in theater?

Harold Prince: I really was interested in theater from the get-go, and that’s very lucky. I went to theater when I was eight years old. Every Saturday afternoon, we went to theater. That was a routine, and they really weren’t particularly, aggressively highbrow eggheads, but they took me to some very odd stuff. The first show I ever saw was Orson Welles in the Mercury Theater production of Julius Caesar as an eight-year-old. That’s pretty strange stuff, and I’ve never forgotten it. You never forget the initial experiences you have. But then I saw all the great actors, and I saw plays, very few musicals. I caught up with a few musicals, but they always struck me as kind of silly, which is why, I suppose, so few of the musicals I’ve done have been appropriately silly.

Were your parents theater people?

Harold Prince: No, not at all. My father was on the Stock Exchange, down on Wall Street, and my mother was what they used to call a housewife. But, as a young person, she had known Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, and she went to school with Dorothy Fields. She had been in an early Rodgers and Hart show. Not professional, it was their last show before they went professional. She sang and stuff. So she had that affection that people have for that sort of thing. So no one ever tried to talk me out of my calling.

Did you like to read as a kid?

Harold Prince: Yeah, a lot of reading with the flashlight under the covers, and a lot of play reading. I caught on to plays as reading matter. I don’t do that much anymore, but I think it must have been a hell of a good idea, because I knew all those plays, all the history of plays from even pre-turn-of-the-20th century, and I read them all and loved reading them, to the exclusion sometimes of great books. And then I got to know very early on — I’m very lucky — I got to know a lot of those playwrights, be in the same room with Robert Sherwood and his like. There were a lot of great playwrights around. Sidney Kingsley I knew very well, and Elmer Rice I met, a whole lot of people like that.

Did you meet all of these people through your mother?

Harold Prince: No, not through my mom. I met them socially. A lot of people. The Rodgers family, Mary and Linda and Dick and Dorothy, they were very generous about young people being around. So you’d spend your Christmas Eve at their house, a lot of young people, Steve Sondheim included. And then I got a job very early. Very early. I got a job with George Abbott, who was one of the preeminent directors, producers, playwrights. He wrote melodramas. He wrote musicals. He directed the first Rodgers and Hart musical, Jumbo. He did all that stuff, and he had a hugely successful career that went for 75 years, and he took me on as a 20-year-old. I had written him, coming out of college. I got out of college at the cusp of 20, right at the end of 19.

Did you study theater in college?

Harold Prince: No. There wasn’t any. I did extracurricular theater at the University of Pennsylvania, and it’s very possible I gave it more attention than I did the credit stuff. But I wrote a letter to George Abbott.

I was terrified of how do you find a job. So I wrote him a letter to his office, and I said, “I don’t know what I could ever do that would be worth any money at this point. I’ve had so little experience. So if you would take me on and make me useful, let me be useful. If you can tell that you are not paying me” — that was the suggestion — “by the nature of what I do, then please fire me right away.” And the letter was so curious that I went there to work and stayed there, and then we shared an office, and then I became a producer. He was the director of the shows that I produced with my partner, and then I became a director, and we shared offices. He died at 107, oh 12, 13 years ago. I’m not certain. But I kept his name on the door until I moved offices. When I moved offices the whole thing seemed a little macabre. My wife said, “You know, I think you’re really overdoing it. You’re in your seventies. You can stop that now.”

What plays really stood out for you that you read as a kid?

Harold Prince: Oh, a whole lot of stuff, like The Adding Machine. That is an Elmer Rice play, wonderful. Clifford Odets. I liked impressionistic plays. I loved O’Neill. Among the earliest plays I read was O’Neill’s The Great God Brown, and it’s a show I ended up directing on Broadway for the Phoenix Theater years later. It got well received. It’s a hell of a complicated play in which people carry masks and confront each other behind masks, then put the masks down and you hear what they are really thinking. It is a device he used later on in Strange Interlude, when people spoke to each other and then spoke to what they were really thinking. What’s interesting about that play, aside from the fact that I loved it, is that it was autobiographical, and if you then look at Long Day’s Journey Into Night, it’s a young man’s covered version of telling that story, because he was a young man when he wrote it. I admired him enormously because he played games with theater, and he knew traditional Japanese theater and German theater and Russian theater, and he used all of those techniques. It is the kind of theater I like, and I gravitate to still.

Some of that stuff is so painful, some of the O’Neill works.

Harold Prince: Childhood is painful. Not everyone’s, but I don’t know too many people that are my colleagues who didn’t have some painful childhood. Not necessarily imposed on you by your parents, certainly not deliberately. It’s probably just something born in you, but I was very solitary, and I escaped into fantasies. This is, by the way, very common. I read Julie Harris at one point said she used to play with a stage and so on, and lots of playwrights have done that, and I did. I had a stage, and I performed things just for me on it. I would listen to the opera on Sundays, and Milton Cross would tell the opera story, and then the opera would start. “The great golden curtain at the Met…” the old Met on 37th Street, “…has gone up. Ladies and gentlemen, Rise (Stevens) is on,” and then I would have set the stage and follow the — but I didn’t speak the language they were singing in. So of course, sometimes I was way behind them, and the great golden curtain would fall. And sometimes I would be finished with Act One, and they would still be singing.

So you were directing even back then.

Harold Prince: Oh, yeah. That’s what I wanted to be. I would have loved to have been a playwright and a director, but I am too introspective for writing. It is very useful to have some facility for writing if you are a director. An articulate director is a good thing. It’s hard to believe, but there are some very successful ones who are not articulate and who are reduced to saying, “No, that’s not what I want. Try something else.” I wouldn’t be one of those guys. I do know how to sort of improvise a scene, and then the playwright will go away and bring it back much improved.

Did you ever do any acting?

Harold Prince: I can’t. I’m terrified. When you direct large companies in musicals, you get everyone from Angela Lansbury, who knows it all, to somebody who is just starting and perhaps doesn’t know anything and hasn’t much training, doesn’t know technique and so on, so you give them line readings, and you actually lay a performance on them, like a coat. That kind of acting, I’ll do. It is very big and embarrassing, but they get the essence of where I am trying to take them.

And what about music? Did you study music?

Harold Prince: I can’t read music, though I’ve directed a lot of operas. Everywhere, in Vienna, in Buenos Aires, in this country, all over the place. I knew John Dexter, the playwright, an Englishman, a very talented guy. He died too young. John and everybody else who was directing in Europe was doing operas as well, and I thought, “What is it about America that has cut that off?” It’s changing now. Peter Gelb is beginning to ask theater directors to direct at the Met, but it is very rare. So I did an interview, and I was asked, ‘What do you want to do?” and I said, “I want to try directing operas.” I got a telegram in Europe from Carol Fox, who ran the Chicago Lyric Opera, which is one of the best opera companies in the country, saying, “How would you like to open our season with Fanciulla del West?” And I thought, “I’ve seen it, but I don’t know it.” I write back and said, “I think I’m very interested. I’ll listen to it again,” and I did open the season and it stayed in the repertoire. It’s in the repertoire, and it’s been done in San Francisco with Plácido. Carol Neblett did it often. That was the beginning. Then I did a lot of stuff.

Do you learn the music by ear?

Harold Prince: You learn the music by ear. I’m that awful thing, the director who walks in with a play script, when they are all working from the score. You see their eyebrows go up, and then suddenly, somebody will say, “Hey, you really do have some sense of music, don’t you?” I’ve done a lot of Puccini, because he’s a great theater man. When I would come to a scene and I wanted to take a pause, I wanted an actor to walk across the stage and open some drapes and look out at the countryside and breathe a sigh of sadness, so did Puccini, because it would always be in the music, and it gave me a hint I was on the right track.

Tell us about your apprenticeship with George Abbott. What were you doing back then?

Harold Prince: I started out being an office boy. The water was in bottles, very heavy, and you came in in the morning and turned them over in the machine, the water cooler. You opened the windows. There was no air-conditioning. This was all in 1948. And then I did the mail, and then if there were odd deliveries, and then I hung around. And then he signed a contract. He wanted to try out television. So he signed a contract. He opened a little firm. He was married then to his second wife, and he opened a firm with some people, and they did some shows, game shows and stuff, and I sort of took the people who were on the game show to the commissary.

But then he signed a contract for an original show. This is all by 1949, and he said it would be called The Hugh Martin Show. Hugh Martin is a great composer who is still alive, and it took place in a living room, and it was a musical show. Butterfly McQueen was in it, playing the maid in those times, and Kaye Ballard was in it, and Hugh Martin and a lot of guys singing and stuff, and Abbott wrote the first show and directed it up at 104th and Riverside drive, up in the hills above the Hudson, and he hated doing it. So he hired another couple of playwrights to write the second show, and the second show came in on a Friday, and he was gone, playing golf somewhere, and I opened the second show. I thought, “He’s going to hate this. This is just not what he’s been doing at all.” So…

Monday morning, I heard a shout from his office, and he said, “Will you come in here? I just got this script from California. Damn, I have to write a whole half-hour television show,” and I said, “I wrote one over the weekend, in case you’d like to see it,” and he said, “Give it to me,” and I gave it to him and he said, “It’s fine. Let’s do it just your way, and why don’t you direct it?” I said, “What are you saying?” He said, “You can direct. I’ve been watching you. Go direct it.” So I said, “Are you going to… the actors… No one is going to listen to a 20-year-old!” and he said — I was probably 21 by then — he said, “No, go ahead. Direct it. I’ll come on Thursday and make some comments.” So the actors did look at me strangely. It bore his name, the script. So we didn’t have to go over that, and I directed the show. He came in and made a nip or a tuck there or something, not much, and the show went on the air. But I was a very abrasive kid. The energy level was just too high. I was trying hard to be tactful, but I had a lot of ambition.

One of the things I never wanted to be was a producer. So when I see myself described as a producer-director, I think, “Okay, I guess that’s history.” But the truth is, it’s not anything I ever wanted to be.

The amount of kinetic energy I gave off, which was clearly spurred by too much ambition, drove them all a little bit nuts, and they went to Abbott and said, “You know, he’s okay, and he knows what he’s doing, but it’s very abrasive. So please come back.” He said, “No. It’s him or no show,” and he stood up for me, and the show went off the air.

I stayed with Abbott, and he knew what I wanted was to be backstage with the show. So the first opportunity he got, he put me as an assistant stage manager on a revue that Jean and Walter Kerr had written called Touch and Go, and it opened here in Washington, D.C., at Catholic University, where they were teaching. That’s the show that first brought them to Broadway, and he brought it in because it got such good reviews.

I went backstage, and my boss was his longtime stage manager, Bobby Griffith, and he decided to show me the ropes, and he did. Then he let me run the show, and that was when it was pretty evident to me, not anyone else — I was one step ahead of the sheriff — that I was not made to be a stage manager. I did two more shows, but I always called the cues the way I would have liked them to be. I changed the tempo of the scene changes just slightly, because I felt like it would be better if these overlapped, it would be better if this moved more. So early on, I would catch the stagehand still moving the scenery. They’d have to fall behind a couch and hang there for the balance of the scene. But that’s the way it happened.

So you were already beginning to direct.

Harold Prince: I was already beginning. Abbott sent me out on the road to look at his shows that were touring. I never knew quite why, because he sent Bobby half the time, and that was what Bobby had always done, but he sent me sometime. Years and years later, he said, “That was your audition. I kept getting reports back saying you had a good rehearsal, you pulled the show together where it was needed, and so on.” So he is the first person who ever said to me, “You really can direct, and you are a director. Be a director.”

But instead, your next move was to become a co-producer.

Harold Prince: When I started out, I was co-producer with Bobby. I got drafted, which is the greatest thing that ever happened to me. The Korean War started, and I was the first person drafted in Manhattan, because I had missed out on World War II, and it took me away for two years and calmed me down. It was not my game plan. It is not the way I saw it playing out. Instead, I found myself in Indianapolis with the National Guard first and then Fort Bliss, Texas, and then I got sent for my second year to Germany with the occupation forces. That was wonderful, because I had never been to Europe, and it introduced me to all of Europe. I went everywhere but England, always by train.

The war was just over. So everything was just demolished in Germany, and yet there were opera houses still functioning, ballet companies still working. There was theater. I was outside of Stuttgart, and I hung out in a little bar in Stuttgart called Maxim’s, which was in a bombed-out church. And there was a little guy, an MC, with lots of makeup and eye shadow and stuff, and there were three huge Valkyrie ladies in diaphanous gowns galumphing around, and you’d have a couple of drinks and watch him try to get a small audience into it, enthusiastic, and he was very obsequious and hard-working and sweat a lot. Years later, in 1966, when we hadn’t quite figured out how to do Cabaret, we’d done a version, and I thought, “It’s not exciting enough.” I drew on that guy and brought a friend in, Joel Grey, and introduced him to Kander and Ebb, and they wrote for him, and that was the MC.

That’s an unforgettable character.

Harold Prince: It makes that whole time in Germany deductible, doesn’t it?

You said it calmed you down. Did it make you less abrasive?

Harold Prince: Yeah. I was aware of that. I didn’t want to dislocate the air. I didn’t want to push people aside. I certainly wasn’t like Sammy Glick in What Makes Sammy Run? or J. Pierpont Finch in How To Succeed In Business, but…

When I came back from the Army, I reminded myself of the problems that I had escaped by being drafted, and so at the top of my calendar on my desk, I wrote two words, and I wrote them for the next five years. “Watch It!” Just “Watch It!” with an exclamation point. So when I’d come in to work in the morning, I would see those two words that were saying, “Calm down,” and I watched it.

You’ve talked a lot about the collaborative nature of theater. Perhaps that abrasive kid would not have been as successful, if you hadn’t tamed him.

Harold Prince: You need to be diplomatic. I think I am diplomatic. I am also older, and when you get to be my age, you inadvertently get some reaction from people. You’ve been around so damn long that you don’t have to work on that, but I think my stronger suit was stimulating people, because I am excitable and excited about what I do, and I think it connects with people. The whole creative process is the biggest turn-on in the world, and I like that. I like collaboration. You have to, if you want to be in the theater. You have to like to give and take.

How did you become a producer? You were very young when you produced The Pajama Game. How did that come about?

Harold Prince: Well, we (Bobby Griffith and I) were in the wings, stage-managing a show called Wonderful Town, which was a huge hit that Bernstein had written the music for. Comden and Green wrote the book and lyrics. Rosalind Russell, the big movie star, was the leading lady. I just got very impatient. I thought, “You’ve been away for two years, you’re back, we really ought to do more with our lives.” Bobby was 20-some-odd years older than I, and adored by everybody, but he wasn’t going to do anything. And so, a little Iago-like, I whispered in his ear, “Let’s move on.” That appealed to him. My energy appealed to him.

There was a review in The New York Times of a book called 7 1/2 Cents, and he was working on something else at the time and could not — he read the review and said, “Read the review, and if you like it, read the book, and if you like it, get the book.” So I read the review, and I rushed and got the book, read it ever so quickly, found the agent, called the agent, went to see the agent, who was a fellow named Harold Matson, a very, very important and highly esteemed fellow. And he had offers from other people because of that review, one of them from Leland Hayward, who was a big-time producer who’d done South Pacific. But he bet on the two kids, or what George always called us, “the kids.” There were a lot of years separating us, but he called us that. Roz Russell heard about it and said “My husband…” who is a movie guy, a nice man named Freddie Brisson — “Will you take a partner?” and we said, “Sure. Raise the money. Where are we going to get the money?” In those days, 250,000 bucks; today, 12 million. So we did do that, and he did bring in some money, and we did the rest by doing backers’ auditions. It turned into the biggest hit of the season instantly, which was a wonderful thing.

However, I stayed stage-managing. Bobby stopped. I stayed. We did a second show the next year called Damn Yankees, and I stage-managed that. I wanted the salary, which was something like $175 a week.

That’s two classic musicals back-to back, and both of them Tony winners, too.

Harold Prince: Yeah. They are not remotely characteristic of my career as a director, not remotely, but I am a pragmatic fellow. When you work with George Abbott, it is a George Abbott musical.

When you work with Jerome Robbins, it’s a Jerome Robbins musical, and then when you work for yourself, you take so much that you observed from other successful directors, but then there is one moment where you have to say, “This career isn’t going to happen the way I want it to happen unless I express myself.” I don’t want to get lost. I have always heard that theory about, “Get lost in the material,” that that’s dearly to be desired, but I don’t believe it for one minute. I think you want to be visible on that stage, and that happened. I did a wonderful show before Cabaret called She Loves Me, but it looked so smooth and tasteful and so on. Cabaret did something else: “Wait a minute. This is different. We have never seen this before.”

In The Pajama Game, were you already working with Bob Fosse?

Harold Prince: Yeah. Bob Fosse was brought to George. He had been on film. He choreographed his own stuff on film with Carol Haney, who was in The Pajama Game and got a Tony Award. He was in the movie, Kiss Me Kate, as one of the dancers. He choreographed their section of one of the numbers, “From This Moment On.” He was married to a dancer, Joan McCracken, who was very famous and was one of the original leading dancers in Oklahoma. She was an Agnes de Mille dancer, and she was married to Bobby, and she said, “My husband is a great choreographer.” So Abbott said, “Why don’t we take our chances?” Everybody practically was new on that show: the composers, Adler and Ross; the choreographer.

The only thing is, if you look at the billing, you will see it says “Directed by George Abbott and Jerome Robbins,” and that was my doing. I wanted to ensure that that show was going to work. It is one thing if the songs are coming in and you can say, “I don’t like that. Write another one,” but when it gets to choreography, how do you know? Abbott said, “What do you want to do?” and I said, “I would love to ask Jerry if he would be willing to stand by.” “Ask him.” So I asked Robbins, and he said, “Only if I can have co-directing credit,” and I said, “Oops,” but I went back to the office and I said to George, “Mr. Abbott…” in those days, “No go. He wants co-directing credit,” and without a pause, he said, “Give it to him.” I said, “What are you saying? He is not going to direct. He may come in if we need him to fix a few dances,” which is precisely what he did, not a great deal, very little. Abbott said, “What do we care? Everybody will know who directed the show.” So that is how he got it, and it served to tell the world that Jerome Robbins wanted to be a director. That’s how he told them.

So this gave you a security blanket?

Harold Prince: Yes, it did. We paid very highly for it, but Jerry was just spectacular at staging.

Did you all recognize that the Fosse choreography was something special at the time?

Harold Prince: Yeah, absolutely. The first time you saw, “Steam Heat,” you could see he had a very, very uniquely defined style, with the hats and the whole thing. Sexy. He too wanted to direct.

Your career as a director really took off with Cabaret. To this day that show seems quite revolutionary.

Harold Prince: I believe it was, and I believe it has been copied probably. You can’t copy West Wide Story. You can’t even copy Phantom of the Opera, though God knows a lot of people have tried, trying to do Dracula or the Hunchback, but you can’t. But Cabaret, you can copy the technique. You can have an MC under a different guise. You can have vaudeville numbers separated from the book. Chicago did that some years later. The Act, the show that Liza Minnelli was in, did that. It keeps coming back as a form. I think we were the first. Nobody is ever the first, but nobody has ever pointed out where it was ever done before.

It also had a dark tinge that hadn’t been seen in musicals before.

Harold Prince: Well, that takes you back to where I went to theater when I was eight years old. Every once in a while, they’d take me to a musical. Let me just share two musical plots with you. One was called Too Many Girls, a big hit of Rodgers and Hart. My mom took me to that, and the plot basically was the ingenues at Pottawatomie College wore beanies, but when they didn’t have the beanie on, it meant that they were no longer virgins. The heroine came out on stage in the second act without a beanie, and the audience went nuts laughing. That was that plot. Another one was an Ethel Merman show called Something for the Boys, and it was a Cole Porter show — big hit during the war — and in it, she’s got graphite in her teeth, and so her teeth inadvertently became a message center for Nazi spies. I rest my case.

So Cabaret had something serious on its mind. Was it risky at that time to put on something that had that gravity?

Harold Prince: I don’t know. I guess it is. You know, when people would say, “They are doing that Nazi musical in rehearsal over there!” none of that ever got to me. I do have a story about West Side Story.

We were in rehearsal, I think, at what is now the Richard Rodgers, the 46th Street Theater, and I am standing on the street, and I was getting some air, and Leland Hayward walked by. I had been in his office working at one point. Abbott had sent me over to work for him. And he said, “What are you doing?” and I said, “We’re doing West Side Story,” and he put an arm on my shoulder, and he said, “Good. It’s time you had a flop,” and walked on down the street smiling. It was meant in a jocular fashion, but it spoke for the industry and what everybody thought. Nobody knows.

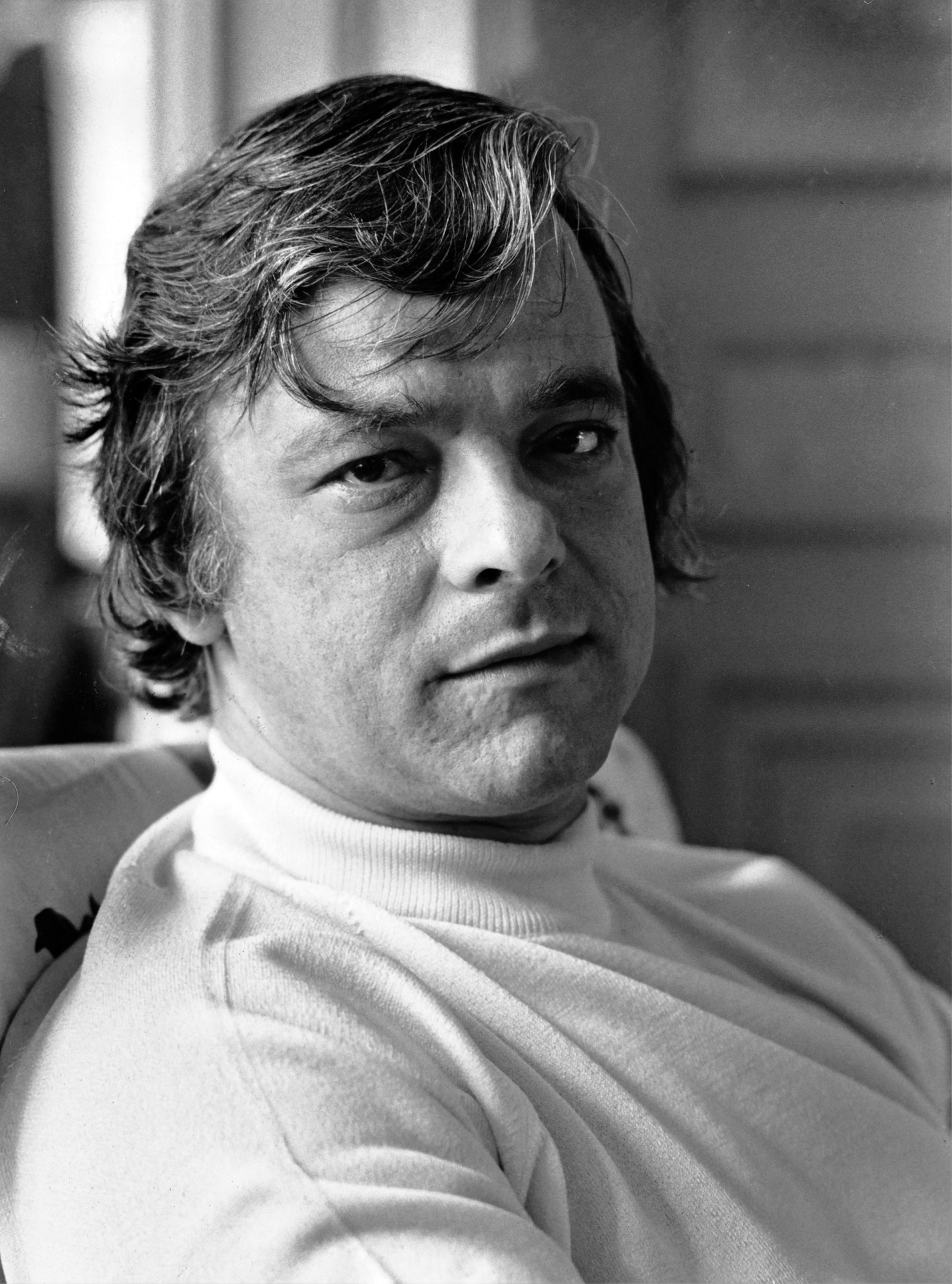

A few years after Cabaret came your first so-called concept musical, Company, with Stephen Sondheim, and that seemed to take yet another step away from the old world of musical comedy.

Harold Prince: Yes, for sure. That was nonlinear. We did two shows in a row that were not linear storytelling.

George Furth had written a bunch of plays, and Steve said to me, “I have a friend name George Furth who has written a bunch of one act plays for Kim Stanley to star in. When you read them, it doesn’t seem to be happening, though she is very interested.” So I read seven plays, and I said, “Well, you know, all I could see reading them — he writes great, Steve — but all I could see was Kim Stanley running to make costume and wig changes and makeup changes. It just exhausted me. That’s as far as my imagination would take me, but I’ll tell you what, it’s a musical.” And he said, “It is?” and he called George and we met in my office, and I said, “Yes, guys. It’s a musical,” and they went and struggled, and Steve brilliantly figured out how to write a score for a show that did not move the show along, where the songs were not internal to the scenes, preserving George Furth’s unique writing and at the same time amplifying the relationships between scenes, interrupting a scene, and doing a number and so on. It’s a very uniquely contrived and brilliant score, and I felt comfortable in the birthday parties, which were dark. It all started with a birthday, ended with a birthday, and they reappeared. They’re right up my alley. That’s something that got added to the show. The show bubbles a lot of the time, but there is a dark spine somewhere there.

How was that received initially?

Harold Prince: Like most of the work, some good reviews, some ghastly reviews. There’s a picture of Steve and me with our arms around each other in dinner clothes, and I had just told him the review in the Times was lousy, and we just kept smiling while the guy took our picture.

This is for Company?

Harold Prince: For Company. But you know, you always have your champions. LoveMusik is very much like that. We’ve had mixed reviews and some spectacular exponents of this form and the way this show works. That’s what you want.

You were also very instrumental in the development of the show, Follies.

Harold Prince: Yeah. It was another show when we started. At first it was called, “The Girls Upstairs,” after a great song Steve wrote. It was a realistic show about a bunch of people who go to a theater and get very drunk and start to fight with props that were on the walls from an old musical. It eluded me. So what happened was we added ghosts, we added other people. We added alter egos for everybody in the cast, and a terrific sense of mystery — À la recherche du temps perdu. We wanted to put something gauzy and melancholy on that stage, while telling the story of lost dreams and so on, and the guys did brilliantly. Then, of course, the apotheosis, the big moment in the thing, was when the four leading characters — and the four leading characters in their youth — all converged on stage, circled each other, screamed at each other, and that erupted in a Follies section, a real Ziegfeld Follies section.

Company got kind of a mixed response. There were a lot of quizzical expressions in the critical community. It’s amazing that, after that, you decided to go even further, in Follies.

Harold Prince: Well, two things. One is Steve said, “I won’t write Company unless you agree to do Follies right after it,” because Follies was ready and Company wasn’t. So I said, “Of course, I do, but we have to get it to this next stage.” So I am sure glad I did it, but that was one of the reasons. The other reason is Company paid back its investment. Follies was the most expensive musical ever done up to that time, with more costumes, more scenery, more everything. It cost $800,000. That’s all. Today, you can’t do a straight play for $800,000.

Unfortunately, we can barely touch on all of these shows that you have been a part of, but we certainly want to hear about Sweeney Todd.

Harold Prince: Sweeney was very much Steve’s show. I didn’t get it. I got it as I went along. It’s about revenge, and I don’t think I am a vengeful guy. I don’t think I feel revenge. I recognize its existence. The idea of it drains me, you know. It hurts my energy level. So it’s about revenge, but I got into it, and I got into it because it’s very possible I imposed something on it. No one else who has done it since has ever done that. I wanted it to have some social significance, and I realized the story takes place during the beginning of the Industrial Age in England, and that all of these people — obviously, it turns to cannibalism — some of them don’t even know that they’re inadvertently cannibals, but basically, I thought they are all sharing one thing. They never breathe clean air. They never see sunlight. From the day they’re born to the day they die, they’re victims. So I said to Eugene Lee, “Let’s do it in a factory, and let’s put a glass roof on it that makes it claustrophobic, and let’s tell all of these people that they are in the same spot really as the two leading characters in the play, that they’re all victims of the industrial age.” This is a time when kids were on the assembly line for 14 hours a day doing piecework and so on, and that pulled the whole show together for me. Oddly enough, it has never been done (that way) since. There certainly are detractors who think, “Why did he bother?” but I bothered because it made it possible for me to direct it, and I did a good job.

Have you seen the recent revivals of Sweeney Todd and Company?

Harold Prince: I have not seen Company. I saw Sweeney Todd with Michael Cerveris. I saw it actually in London first, with that company, and it was so totally different that I had a fine time. Honestly, I didn’t think it was clear. It ran for eight or nine months, but I think a lot of the audience had seen the show before, so they could follow the story in the second act. I wasn’t sure they could remotely follow the story if they didn’t have some familiarity with it, because it is a very complicated story.

You and Sondheim had a big disappointment, initially anyway, with Merrily We Roll Along.

Harold Prince: That was a big flop. That was a disaster, and we worked very hard and made quite a good show of it. I think we were hurt by a decade of what seemed to everybody like unceasing success and too many awards and too much publicity that you don’t seek. I think it hurt us. So we were not allowed to work on it. Everybody watched it, from the first preview, when it wasn’t working, until it closed, when we thought it was well on the way to working. If it had had someone else’s name on it, it might very well have gotten a chance. There’s a small story there where I was not true to myself, and I will always feel guilty.

Whatever I did with that show, I was convinced that it should be done Our Town style, on a bare stage in a theater with nothing, and just some racks of clothes that kids would put on to play scenes, and I called my office together, my staff, and I said, “I can’t see this show in scenery. I can’t see this show in costumes. These kids are playing life, and it goes awry.” It’s backwards in time, and they said, “You must do what you must do,” and I didn’t, because I thought, “We’re going to charge people… ” whatever it was in those days, $20 a seat. “We are going to charge them to walk into a theater where there’s nothing on the stage.” And I didn’t have the guts. Big mistake. I should have done that, and you know, I regret it.

That show is coming back.

Harold Prince: It comes back. It comes back often, and they just keep changing it. They do it with older people playing young people. I still prefer young people playing old people. I still think that was right, but they’ve never brought it all the way back. Eric Schaeffer did a production here that they thought would get to Broadway. It hasn’t. Steve Sondheim’s score is dazzling. Furth’s book is wonderful and a little complicated in places. But really, I will never get past wishing I had listened to myself, but I ran scared.

Tell us about working with Andrew Lloyd Webber. What drew you to this very different world?

Harold Prince: That started with Evita, one of the shows I am proudest of. He and Tim Rice came to me. I was living in Spain. We were living in Majorca, and Tim actually arrived with a tape of this show about Eva Peron, and he played the tape, and I listened, and the opening number, which had been recorded by the London Symphony Orchestra — they had that kind of money to do that — and with a huge chorus, and I said, “This opening is 200,000 people in front of the Casa Rosada at Eva’s funeral. Wow, it’s so exciting I can’t stand it! How the hell do you do that?” and I was hooked. So I sat down, listened to all of it, thought it was all marvelous, and wrote a 3,000-word letter saying what I thought should happen and what I would love to do, and I got back a letter saying, “We’re doing a record, and your letter’s terrific, but it is going to slow us down and just make us lose confidence. So thanks so much for the time and trouble,” and I thought, “I’ll never hear from them again,” and they went on and did the record. A year and a half later, the record came out. It was a huge hit in Europe, and I am sitting in my office, and my receptionist says, “There are two young men in the front office who want to see you. They don’t have an appointment,” and I said, “I’ll look.” I looked. It was them, and they said, “We wanted to bring you the record. Now we’re ready. Are you ready to do the show?” and I said, “Sure.”

I was busy, and they had to wait another year for me, but it was one of the most exhilarating and extraordinary experiences. I insisted they put some spoken dialogue in it, not much, but in key places. Mostly, it’s numbers. It’s a sort of Brechtian style, and the energy of it really worked for all of us, and this show worked immediately in London. So that was my introduction to them.

The next time around, they had broken up. Tim was working on Chess, and Andrew wanted to do Phantom of the Opera. I was sitting in a restaurant, and he was sitting at the next table with Sarah Brightman, to whom he was then married, and he said, “Come over and have coffee,” and he said, “I am thinking of Phantom of the Opera as a musical. What do you think?,” and I said, “It is the perfect time for a romantic musical. Perfect. There hasn’t been a romantic musical in years, and that’s what I would like to see.” That’s often a criterion. I very often do what I wish I could see when I went to the theater. So it is sort of make your own theater really, and I signed on immediately, and we spent the next two years working on it. I spent a lot of flights back and forth to London. The scenery itself took nine flights there, and about three for (designer) Maria Bjornson. It needed to take an audience where an audience probably could not remember being, but it needed to take them back to being me, seeing Orson Welles at the age of eight in Julius Caesar. You needed to go in there and say, “I’ve just lost all my problems,” all the years of patina that have developed, and crust, and just be in this other world, and insofar as it does that, it seems to have succeeded in its objective.

The size of that whole show was risky, wasn’t it? It’s such an extravaganza.

Harold Prince: Yeah. I think it was risky. It was fun. There’s a funny story attached to it.

Our rehearsals started at 10:00 every morning in Lambeth, in a school, in a gymnasium, and when I would leave, having staged a section of it, sometimes 12:30, and then I would leave my assistant to review what I’d done, and then Gillian Lynne would take the rest of the time for choreography. There was some choreography in the show, and I wouldn’t come back until the next day. So we rehearsed it for four weeks. At the end of four weeks, we had a run-through. At the end of the run-through, I said, “Next Monday, we meet in Her Majesty’s Theatre. I’ve been over all of the props and the effects, and we are ready for you, and you have done a wonderful job.” One of the cast raised a hand and said, “I have been delegated to ask you a question,” and I said, “Go ahead. What is it?” “What do you do in the afternoon?”

I had never rehearsed in the afternoon. It just hadn’t been necessary.

What was your answer?

Harold Prince: Oh, I made a cheap joke. I said, “I watch Coronation Street,” which is a soap opera. I am sure it’s not on in the afternoon. What I did was walk around a lot. I read. Anyway, we played nine previews. The final of the nine previews was the opening night.

That speaks of such confidence and discipline. You knew what you wanted to accomplish, you accomplished it, and you left.

Harold Prince: Maybe foolhardiness. Who knows? It worked in that case.

Is that how you work as a director? Are you really organized about what you want?

Harold Prince: I am very organized. I don’t sit around and do little dots and drawings. When you first start directing — the very first job I ever got, which was a stock job, directing — you do little drawings of where you want your actors to go in the scenery. The first play was Angel Street. You know. Gaslight, I think the movie was called. And then you go in and you start to rehearse the actors, and then the actors, one of them says, “I would love to try going in that direction instead,” and there is your whole job gone. Somebody who goes somewhere you didn’t want them to go, what about all the rest of those people? So preparation is another kind of thing. Preparation is getting everything you need to know of a sensory nature about the characters, where the story is taking place, all those things. I mean what things smell like, taste like, sound like, and so on. That is an exercise you share with your designer as well. Boris Aronson taught me that years ago.

Didn’t he work with you on Cabaret?

Harold Prince: Fiddler on the Roof, Cabaret, Follies… He was the greatest designer that ever lived, I think. He would never design anything. I never saw him pick up a pen and draw something and say, “What do you think of this?” Instead, he’d say, “Let’s talk about the food. Let’s talk about what the restaurants were like. Let’s talk about the sound on the street. Let’s talk about…” So Cabaret, for one, was a black box with selective bits of scenery and one huge surprise. I looked at the model for the first time, and there was this waffled, wobbly, funhouse mirror angled at the audience. They came in and sat down, they could see this distorted view of themselves, and it’s like saying, “That’s your metaphor, folks!” Sort of like the factory in Sweeney.

What were the most meaningful legacies of people in your life, like George Abbott? What did you learn?

Harold Prince: Well Abbott, very simply, told a lot of people the same thing: self-discipline, that the theater is a job you have to do. You have no time to indulge because you are making, quote, “art,” end quote. Show up on time, get the work done. That’s a huge thing to learn.

Don’t you find you sometimes have to indulge the artists you work with?

Harold Prince: No, no. Honor their difficulties, but don’t encourage their neuroses, because nothing creative comes out of that. Abbott was also the one who said, “You’re a director.” All you need in this world as a young person is one person who knows and who you respect to say, “You can do this. Do it.” Because most people are telling you, “You can’t” and “Don’t.” I also learned something quite interesting from Jerry Robbins.

I have two left feet, but my direction is characterized, I think, in some of the best work, by movement, and by how I will move a block of people you would call an ensemble or a chorus. And they are moving the way dancers would move. Their feet aren’t doing anything, because I wouldn’t know how to tell them that, but I can move them. Jerry moved people diagonally across the stage, from upstage down, directly downstage, turn around, move directly upstage. Strange energies come from all of that. The theater that he entered and that I entered moved laterally. They’d drop a drop, and things would move from left to right or right to left. They changed the scenery upstage. You would open… there would be doors. I haven’t had a door in a show for as long as I can remember. That whole world of inviting the audience to use its imagination and fill in the blank spaces is the difference between what I do and what people who do realistic films and so on do. Films weren’t always realistic. I love old black-and-white silent films. They were forced perspective and all kinds of strange wonderful things that I use in the theater.

That also speaks of a respect you have for the audience, that they will be able to fill in the blanks.

Harold Prince: I should also mention Orson Welles. I am a huge admirer, as you know, of Welles. It started with that Mercury Theater production. I do think Citizen Kane is as nourishing to me, a theater director, as anything I have ever done. Some of the work I have done is an homage. If you take a look at the opera scene in Phantom of the Opera, believe me, I wasn’t thieving, but I was certainly totally paying homage to the opera scene in Citizen Kane.

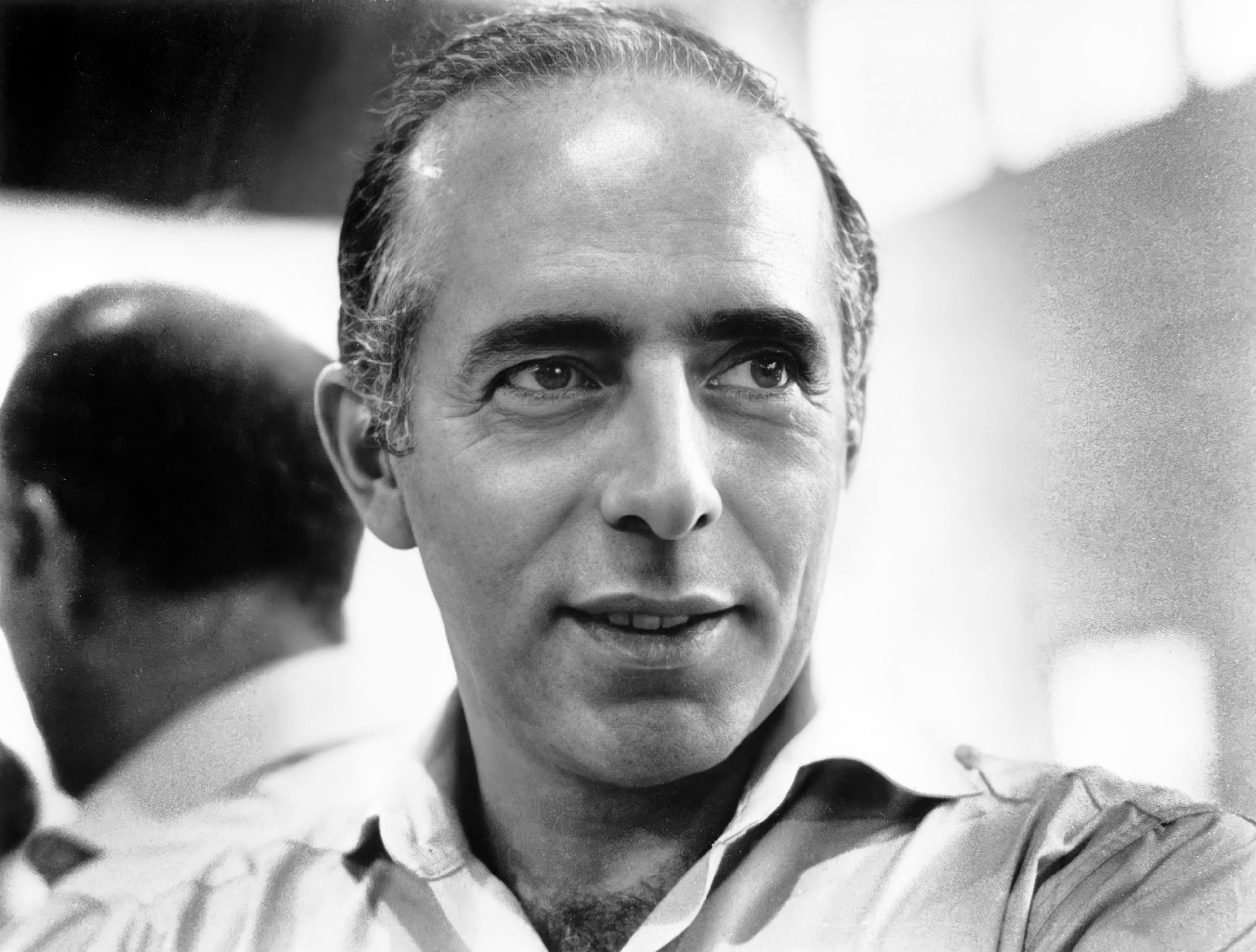

You mentioned Kazan, also.

I thought he (Kazan) was just wonderful. I love larger than life. I love people tearing into the theater and saying, “It is a black box.” The energy! There is an energy there that you can really harness, that is harder on film. Kazan made some great films. On the Waterfront is such a great film, and the film version of Streetcar is extraordinary, but Streetcar seems like the play to me, seems like a play in a claustrophobic place, with people giving performances that they gave on the stage.

For all of the great classic musicals we have been talking about, there were some failures along the way.

Harold Prince: You bet.

Even with the breadth of experience that you’ve had, can you ever know for sure if something is going to succeed or not?

Harold Prince: No. You really don’t know.

It is also very important that you make the distinction between “success and failure” and “hit and flop.” Follies was a huge success that lost all of its investment money. Hits are shows that do well at the box office, and some of them, I wouldn’t want my name on.

It must be very painful when things don’t work out the way you hope. How do you keep going?

Harold Prince: It’s more painful to a whole lot of other people. I don’t nurse things, and I move on. I don’t spend a lot of time looking back. I am very lucky. I have been married a long time now, for 45 years, and I have somebody who loves the theater and is extremely encouraging and encourages the hard part of it, the part where I am risking much more.

I have a show right now called LoveMusik which has played a limited engagement in New York, ten weeks or something, but to full houses, and I am as proud of it as anything that I have ever worked on. I am sure it will be back, from the amount of interest there is in Europe and around the world. It is going to be done in London and in Tokyo and in Israel, and all this in just these 10 weeks. The contracts are all out. So that’s what I’m working for now, because it’s authentically its own show. Those people who do not recognize it in a comfortable way are the same people who were walking out on West Side Story. What we are talking about is the difference in audiences today and just a whole shift in the entertainment industry. It is focused on making money, not often, but infrequently hitting the jackpot. And that does happen infrequently.

When LoveMusik was opening, you said in an interview that you weren’t quite sure what to call it, in terms of form. So you’re still definitely pushing the envelope.

Harold Prince: Well, it is the most fun I have had in a very long time. We went back and sat the other night, and it just makes me feel good that I still have those priorities and the energy is there. I love the people I worked with. Not only the cast, who are extraordinary actors, but Jonathan Tunick’s orchestrations are magnificent.

Wasn’t it hard to get the Kurt Weill Foundation to agree to using his music?

Harold Prince: It’s never easy to get the Weill Foundation, but they trust me. Also, I worked with Lotte Lenya in Cabaret, and we were very close. Now I am some sort of emeritus member of the Weill Foundation. She actually put me on the Kurt Weill Foundation before she died. She was forming it, and she said, ‘We need somebody young.” Is that a laugh? I was younger than most of them.

You’ve got more new projects, don’t you?

Harold Prince: I have another one. A big musical this time. Maybe a year and a half away. It’s written. The book is by Richard Nelson, who is a great playwright and quite well known here and in England. The lyrics are by Ellen Fitzhugh, who sort of took a break from the theater to have a family, and she is back working. Jonathan Tunick is co-writing the score with someone else. I am going to keep that a secret. It’s based on a book by the marvelous Austrian novelist named Joseph Roth, who wrote The Radetzky March, which is a great novel. This is based on another one.

Well, long may you direct and produce. Thank you for this great interview.

Harold Prince: It was a great pleasure.