I grew up in Germany during the Nazi period, and I came to this country when I was 15. And then I had to work in a factory because we had no resources. And I went to night school. So, it was not a rational ambition for me to become a world statesman.

Henry Alfred Kissinger was born in Fürth, Germany, a medium-sized town neighboring the larger city of Nuremberg in Northern Bavaria. His father Louis taught in the local gymnasium, or college preparatory school. The family valued education, although young Heinz, as he was then known, preferred soccer to studying. Like many of the Jewish families of Fürth, the Kissingers enjoyed a secure position in the community until the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party. Louis Kissinger was fired from his job and the family lost all the rights of German citizenship. Eager to leave, the Kissingers faced the same problem as the other Jews who fell under Nazi rule, the difficulty of finding a country to take them in. In 1938, the Kissinger family — mother, father and two sons — received permission to enter the United States by way of London. The rest of the extended family remained behind in Germany, where most of them perished. The Kissinger family settled in the Washington Heights section of Manhattan, among other German Jewish refugees.

The 15-year-old Heinz became Henry and applied himself to his studies, but after his first year at George Washington High School, his family’s precarious finances compelled him to take a full-time job in a shaving brush factory. He continued to study for his diploma at night, and after completing high school he entered the City College of New York, where he studied accounting. He was thriving academically when he was drafted into the United States Army in 1943.

While in basic training, he became a United States citizen at age 20, and joined his unit, the 84th Infantry, in time for the Battle of the Bulge. A superior officer, fellow German refugee Fritz Kraemer, was impressed with young Kissinger and assigned him to the military intelligence section of the division. Private Kissinger volunteered for dangerous duty and was soon promoted to sergeant in the Counter Intelligence Corps. He was given responsibility for re-organizing civilian administration in liberated towns in Germany, and won a Bronze Star for hunting down Gestapo officers and saboteurs. Sergeant Kissinger was teaching at the European Command Intelligence School when he received his discharge. He continued teaching at the school as a civilian employee for some months after his separation from the Army.

The G.I. Bill enabled Kissinger to return to college. He won admission to Harvard, where he received his undergraduate degree in history, summa cum laude, in 1950. He remained at Harvard to earn his graduate degrees. On completing his masters degree in 1952, he became Director of the Harvard International Seminar. With the completion of his doctorate in 1954, he joined the faculty of the Department of Government and the new Center for International Affairs.

Kissinger’s doctoral research on the diplomacy of post-Napoleonic Europe provided the foundation of his first book, A World Restored: Castlereagh, Metternich and the Restoration of Peace, 1812-1822, published in 1957. The same year saw the publication of his first book on current affairs, Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy.

While teaching at Harvard, Kissinger served as a consultant to the National Security Council, the Council on Foreign Relations, the Rand Corporation, the State Department, and the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency. As Director of the Special Studies Project for the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, he came into contact with the Governor of New York, Nelson Rockefeller. Kissinger became a foreign policy advisor to Governor Rockefeller, supporting the governor’s three campaigns for the presidency in 1960, 1964 and 1968. Although Rockefeller never won the Republican nomination he had sought, Kissinger attracted the attention of the man who defeated Rockefeller for the nomination in 1968, Richard Nixon.

After winning the national election in 1968, Nixon appointed Kissinger to serve as National Security Advisor. When Nixon and Kissinger arrived in Washington, the U.S. was deeply embroiled in the Vietnam War, and peace talks in Paris had stalled. During his campaign, Nixon had promised “peace with honor.” In office, President Nixon gradually reduced the American role in ground combat, while escalating the bombing campaign against North Vietnam. Nixon ordered incursions into neighboring Cambodia, provoking bitter protests at home, while Kissinger focused on trying to negotiate a ceasefire with North Vietnam.

Nixon had first made his name as one of the most vigorous anti-communists in the U.S. Congress, but Kissinger made his top priority the promotion of a policy of détente, or relaxation of tension, between the United States and the Soviet Union. He initiated strategic arms limitation talks (SALT) with the Soviets.

Kissinger’s efforts drew criticism from both ends of the political spectrum, from liberals who favored a more rapid withdrawal from Vietnam and from conservatives who distrusted his outreach to China and the Soviet Union. Although Kissinger himself disowned the term, his foreign policy approach was often described as one of realpolitik, the pursuit of a nation’s interest based on immediate practical considerations, rather than adherence to a set of fixed principles or ideology.

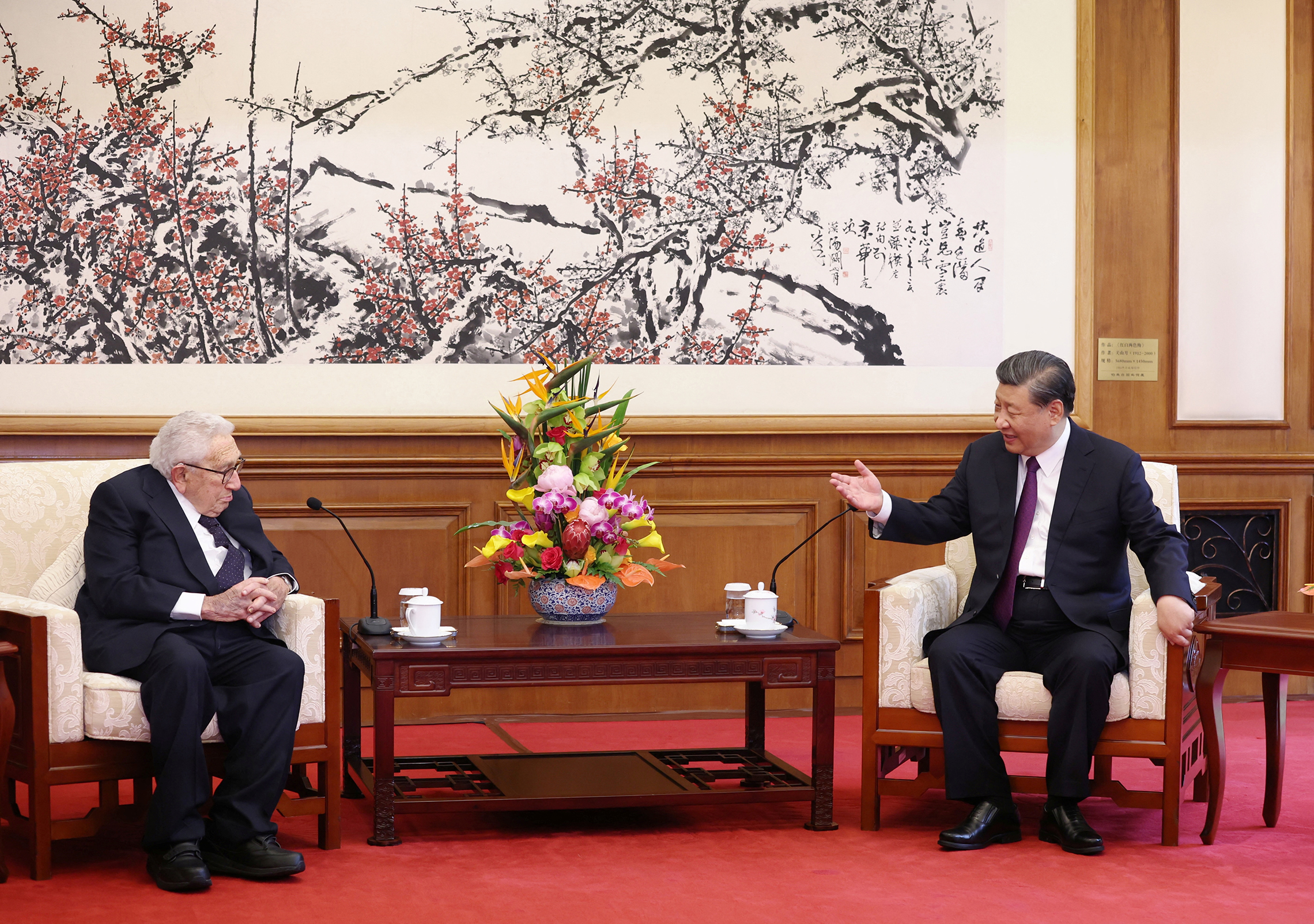

Kissinger sought to exploit the growing tensions between the two communist powers, China and the Soviet Union, by playing one against the other. Since the communist revolution of 1949, the United States had had no diplomatic relations with the government in Beijing. In the summer of 1971, Kissinger made a secret trip to China and initiated a process that would eventually lead to full diplomatic recognition and the integration of China into the global economy. In 1972, he arranged for President Nixon to meet in Beijing with Mao Zedong, the Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party. This was a virtual earthquake in world politics. Kissinger and Nixon’s decision to “play the China card” is widely credited with inducing greater cooperation from the Soviet Union in the arms limitation talks, resulting in the SALT I Treaty and the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty.

In October 1972, Kissinger and the North Vietnamese negotiator, Le Duc Tho, drafted an agreement, and with the American presidential election only a few weeks away, Kissinger announced that “peace is at hand.” President Nixon was elected to a second term in a 49-state landslide. The Paris Peace Agreement was signed by all parties the following January. Kissinger and Le Duc Tho were awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace. Le Duc Tho refused to accept his award; Kissinger announced that he would donate his prize money “to the children of American service members killed or missing in action in Indochina.

It had long been apparent that Kissinger had the greatest influence over the president in matters of foreign policy, eclipsing that of his Secretary of State, William P. Rogers. In the first year of Nixon’s second term, Rogers stepped down and Kissinger succeeded him as Secretary of State, while retaining the position of National Security Advisor.

Another controversial aspect of Kissinger’s tenure was the administration’s policy in the southern cone of South America. In Chile, the military overthrew the government of the elected president, Salvador Allende, a socialist sympathetic to communist Cuba. In Argentina, a military coup ousted President Isabel Perón, widow of the populist strongman Juan Perón. The CIA played a role in destabilizing the Allende regime, and the United States was quick to recognize the new regimes in both countries. In Kissinger’s view, the stability offered by reliably anti-communist regimes was preferable to the risk posed by unstable or openly hostile governments in the Western Hemisphere. Many years elapsed before the return of electoral democracy in Chile and Argentina, and the U.S. role in their history remains a sore spot in hemispheric relations.

The major international crisis of Nixon and Kissinger’s second term was the Yom Kippur War of 1973. With the Soviet Union supporting Egypt and Syria, and the United States supplying Israel, the conflict threatened to escalate into a confrontation between the superpowers. Kissinger helped persuade the combatants to accept a UN-proposed ceasefire. When a peace conference in Geneva failed to produce an agreement, Kissinger undertook “shuttle diplomacy,” flying back and forth between direct meetings with the Israelis, the Egyptians and the Syrians. His labors eventually produced a disengagement agreement, with the institution of UN buffer zones between Israel and its two hostile neighbors. The war had strained Egypt’s relations with its longtime patron, Russia. Kissinger seized the opportunity and cultivated a relationship with Egypt’s President Anwar Sadat. With Kissinger’s encouragement, Egypt gradually moved from the Soviet orbit to the American one.

Kissinger planned further foreign policy initiatives for President Nixon’s second term, but the president soon became hopelessly mired in the Watergate scandal. Nixon resigned in August 1974. His successor, Gerald Ford, retained Kissinger as Secretary of State, and sought to maintain continuity with the Nixon administration.

The United States had ended its ground operations in Vietnam, but the North Vietnamese failed to honor the peace agreement and resumed their advance in South Vietnam. When the capital, Saigon, fell to the communist forces in 1975, Kissinger offered to return his Nobel Prize medal to the Norwegian Nobel Committee.

Gerald Ford sought a full term in the presidency but lost to Democratic candidate Jimmy Carter in 1976. In his last month in office, President Ford awarded Kissinger the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. Kissinger’s term as Secretary of State ended with Carter’s inauguration in January 1977.

After leaving office, Kissinger wrote, lectured and consulted widely, teaching at Georgetown University’s Edmund Walsh School of Foreign Service. He also revisited an earlier interest, serving as Chairman of the North American Soccer League. In 1980 he received the National Book Award for his memoir, The White House Years. He has since continued his life story in Years of Upheaval and Years of Renewal.

In 1982, he founded a consulting firm, Kissinger and Associates. In the 1980s, President Ronald Reagan and some of his advisors initially sought to disassociate themselves from Kissinger’s policy of détente, and the arms limitation process, but eventually pursued a similar course themselves. President Reagan called on Henry Kissinger to chair a panel on Central American policy. Following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States, President George W. Bush invited Kissinger to chair a commission of inquiry.

In recent years, Henry Kissinger has joined with former Secretary of State George Schultz, former Senator Sam Nunn and former Secretary of Defense William Perry in calling for the complete phasing out of nuclear weapons. His books on international affairs include Diplomacy (1994) and Does America Need a Foreign Policy? (2001).

At the time of his 2000 interview with the Academy of Achievement, Kissinger was at work on his book Vietnam: A Personal History of America’s Involvement in and Extrication from the Vietnam War (2002). His books since then include On China (2011) and World Order (2014).

In 2021, Kissinger co-wrote a book about artificial intelligence titled “The Age of AI: And Our Human Future”, warning that governments should be prepared for the potential risks associated with this technology. Following this, in 2022, he authored “Leadership: Six Studies in World Strategy,” examining the distinct strategies of six extraordinary leaders. He posited that leaders balance knowledge from the past with uncertain future intuitions, setting objectives and crafting strategies accordingly. He highlighted the strategies of Konrad Adenauer, Charles de Gaulle, Richard Nixon, Anwar Sadat, Lee Kuan Yew, and Margaret Thatcher, weaving historical insight with personal knowledge. The book culminated in reflections on today’s world order and the critical role of leadership.

On May 27, 2023, Henry Kissinger celebrated his 100th birthday, having outlived many of his political contemporaries who helped guide the United States through significant historical events, including the presidency of Richard Nixon and the Vietnam War. His son, David Kissinger, wrote in The Washington Post that his father’s centenary could have been predicted by those who knew his force of character and passion for historical symbolism. Despite his age, Kissinger remained remarkably active well into his 90s, outliving many of his peers, notable critics, and students.

In honor of his centenary, Kissinger undertook a series of visits to New York, London, and his birthplace, Fürth, Germany. Throughout recent years, he maintained significant influence over Washington’s power brokers in his role as an elder statesman. He provided counsel to both Republican and Democratic presidents, including during the Trump administration, while keeping up an international consulting business. His speeches, often delivered in the German accent he retained since escaping the Nazi regime as a teenager, were marked by his unique insights and perspectives.

As recently as the previous month, Kissinger commented on major global issues, suggesting that the war in Ukraine was nearing a critical point with China’s entry into negotiations. He predicted these negotiations would reach their peak by the end of the year, consistently advocating for peace through negotiation to resolve the conflict.

Few figures in the history of diplomacy have had as large an impact on world history as Dr. Henry Kissinger. As National Security Advisor and Secretary of State, Dr. Kissinger is generally credited with crafting the policy of détente with the Soviet Union and effecting the historic opening to China. He was awarded the Nobel Prize, along with Le Due Tho of North Vietnam, for negotiating a ceasefire agreement in the Vietnam War.

Henry Alfred Kissinger was born in Fürth, Germany. Fleeing the rise of the Nazis, the Kissinger family came to the United States in 1938. He became a United States citizen in 1943 and served in the U.S. Army during World War II. From 1954 until 1969, he was a member of the faculty of Harvard University.

President Richard Nixon selected Henry Kissinger as Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs in 1969. Dr. Kissinger retained this position throughout the Nixon administration, even after being appointed Secretary of State in 1973, a position he retained in the subsequent administration of President Gerald Ford. Under President Reagan he chaired the National Bipartisan Commission on Central America, and served as a member of the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board from 1984 to 1990. Today, Dr. Kissinger is Chairman of Kissinger Associates, Inc., an international consulting firm.

(Dr. Henry Kissinger was interviewed twice by the American Academy of Achievement — on June 8, 2002 at the Summit in Dublin, Ireland and on September 22, 2016 at the New York Public Library in New York City. The transcript draws on both interviews.)

When you were growing up, did you ever imagine you would become a world statesman?

Henry Kissinger: I grew up in Germany during the Nazi period, and I came to this country when I was 15. And then I had to work in a factory because we had no resources. And I went to night school. So it was not a rational ambition for me to become a world statesman. Then I became over time a professor and I wrote about world history, but I was not an active participant. In 1968, President Nixon, newly elected, invited me to become his Security Advisor. And as the Security Advisor all the problems that have to do with national security flow through the Office of the Security Advisor to the President. So it is in that period that I became an active participant because President Nixon sent me as his principal negotiator to negotiate the end of the Vietnam War, the opening to China, and three Middle East peace agreements.

What did you say when you got that call from President Nixon?

Henry Kissinger: I had been really advisor to Governor Rockefeller, who was an opponent within the Republican Party of President Nixon. So when President Nixon offered me that position, I said, “I need to talk to Governor Rockefeller, with whom I’m associated.” And Rockefeller said to me, “Think about it this way, he is taking a much bigger chance on you than you are taking on him.” And so then I accepted the job.

When President Nixon asked you to serve as National Security Advisor in 1969, the U.S. was already deeply involved in the Vietnam War. Why were we involved there, and why did it take us so long to extricate ourselves?

Henry Kissinger: The first thing to remember is the Nixon administration actually did not get involved in Vietnam. We found the war and our task was to liquidate it.

In retrospect, we got involved in Vietnam because we thought that the tragedy in Vietnam was a part of a vast communist system and that the way to resist global penetration of communism was to fight it wherever it occurred. That was sort of the accepted view and it was done in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. I think in retrospect it was a mistake. It was an honorable mistake by people carrying out the traditions of previous American foreign policy. The question of how do you get out when you have 500,000 troops in place and you have a million allied troops and about the same number of hostile troops, how you can get out without producing a catastrophe, and secondly, how you can get out without undermining the face of the United States. That was the problem the administration which I served faced, which had inherited 550,000 troops in place. We thought the honor of the United States required a gradual extrication. There was no dispute about getting out. The dispute was how to get out, and under what conditions. It was easy to take heroic stances, carrying placards around. Those were not the people who had to implement the decisions.

There is still bitterness and confusion about the war. There are even people who believe that we left American prisoners behind.

Henry Kissinger: That is ridiculous, absolutely ridiculous that we left American prisoners there. There is not a shred of evidence that American prisoners were left. There have been Congressional hearings that went into everything. When you think about it rationally, why would an American administration that is accused on the one side of having fought unnecessarily end it by leaving American prisoners there? That is not a rational accusation.

The question arose because of soldiers who were missing and never accounted for.

Henry Kissinger: Being not accounted for has to do with the difficulty of the terrain. The Vietnamese had an obligation to account for the missing. They seemed to have a warehouse of bones. Every time they wanted to make an impression on America, they give us a few bones. That is a disgrace.

Looking back on that war with the hindsight of so many years, would you have advised differently?

Henry Kissinger: I have written a book that will come out which will discuss what we did. The administration which I served found 555,000 troops and we got them out. There can be a lot of heroes with retroactive consideration who can have brilliant ideas about what should have been done and what might have been done. We did the best we could under the extremely difficult circumstances. There is nothing I would significantly do differently.

We’d like to discuss the opening to China. Why was establishing diplomatic relations with China so important in your view?

Henry Kissinger: It is a fifth of the human population. It was not natural for the United States and China to have no contacts. It made it extremely difficult to conduct foreign policy when on every issue China was considered an enemy. Therefore, we thought we were serving the cause of peace by bringing China into a relationship with the United States and thereby with the rest of the world because China didn’t have contact with any other country either. So, we led the way into dialogue with China and thereby made it possible to have a wider international system.

You were born in Germany. How did the coming of Hitler affect your father and the rest of the family?

Henry Kissinger: My father was a teacher in a middle school and he lost his job, which was something that never happened in his life. So, the condition of our family changed from being members of the community to being a discriminated minority. I was a kid, and children adjust to everything, so I can’t say that – I mean any of these people could be run up on the street. They almost became part of the existence. I didn’t realize how hard that was until I came to the United States. So I can’t say that I’ve suffered deeply, but I developed understanding. When I teach at public schools at New York, I understand what minorities feel.

How much of your family came to America with you?

We were very lucky that my parents and my brother — so the whole nuclear family came together. About 15 of our relatives, that is brothers and sisters of my parents and grandmother, didn’t make it. But the nuclear family, we were all together.

Henry Kissinger: Well of course for my family and me, coming to America saved our lives. But more important than that, we lived in a totalitarian state, and when we came to America, and we could see how people talked to each other and dealt with each other, that was a liberating experience. And I wrote an essay in high school about coming as a refugee, and could you find many things different, and you miss many things. But then you remember that you can walk across the street with your head erect and then that makes it all worthwhile.

How did you first discover your direction in life?

Henry Kissinger: The military service was tremendously important because I came to this country, as I said, as a refugee. And I lived in a section of New York where there were also a lot of other refugees. So it wasn’t in the Army — until the Army that I met, what you would call “average Americans” on a regular basis. In the factory in which I worked, there was mostly Italian refugees or Italian immigrants. It wasn’t so much refugees. In my military service I was with the 84th Infantry Division. And that division was composed of people from Northern Illinois and Southern Wisconsin. And that was and is sort of the heartland of America. So it was tremendously important in teaching me about how the typical, average American thinks, and in the Army you are dependent on each other, and nobody really cares what you did before, and it was an absolutely formative aspect of my life — I can’t say I enjoyed digging foxholes and things like this, but in retrospect it was a very important part of my life.

An instructor you met in the Army commented that you had a very sharp mind, deeply attuned to history. I know you are a musical person. Where does that sense of history come from?

Henry Kissinger: I can’t really tell you because when this man said this, it was news to me. He turned out to be a man who affected my life by calling my attention to some of these qualities. If I can describe it, having seen failure early in my life, how an apparently normal existence can disintegrate under the impact of dictatorship and the imposition of force, and therefore we reflect about how one can mitigate or avoid such conditions.

Who was this Army instructor?

Henry Kissinger: He wasn’t really an instructor. He was a very odd personality, actually. He was a German, not Jewish, and left Germany out of conviction. He was much older than I and had been drafted into the Army. He had a stupendous education and he was doing odd jobs for division headquarters. I heard him speak once and dropped him a note, which I practically never do. And so, we got to know each other. For about 20 years afterwards, he became somebody that I took very seriously. Then, when I got into government, he thought that I was making too many agreements with the Soviets and our relations then ended on his side. But he was a huge influence in my life.

What was his name?

Henry Kissinger: Fritz Kraemer.

You reached the highest levels of the American government with a very distinctive accent. How did people react to that?

Henry Kissinger: I was sort of self-conscious about my accent, but in the Army nobody ever mentioned it. So I thought I had lost it. It wasn’t until I got out of the Army back to Harvard that people started asking about my accent. By the time I was in office, it had become sort of a trademark and not consciously, but so then people didn’t ask me about my accent. They sometimes made — It became a subject of benevolent jokes. But we didn’t get much hate mail about my accent.

Did your father and mother urge you to achieve? Were they ambitious for you?

Well, my father was a teacher in Germany. And he was of course very interested, as these parents generally were, that I would be a good student. But when we were in Germany I have to say I was more interested in football than in studying, and I got pretty good grades, but nothing outstanding. But then when I came here then I became a good student.

What changed?

Henry Kissinger: Well it was one way to distinguish myself. I knew I wasn’t going to be a great football star anymore.

What made you want to distinguish yourself?

Henry Kissinger: I guess it is something born into you, but I’ve been lucky in the sense that all of my life, that I could control, I was enabled to do what I love doing, and what I’m most interested in, which is study of history, study of foreign policy, and the execution of foreign policy. And I had the good fortune that all my life, even today, I could still combine all of these. I know people always expect you to say that you have some crazy regret, and as everybody I didn’t get everything at the time that I wanted, but the major direction of my life was the way that I wanted it to go. And so I think I was extremely fortunate.

I think it must be genes. My father was very studious, and my mother was extremely energetic. And so I did an outstanding job in picking my parents.

When you talk to college students and young people who want to use their lives to make a difference, what advice do you have for them?

Henry Kissinger: There are a lot of ambitious younger people, and some of them have a specific job that they think they want to do. I always tell them, do what most interests you in any one year in which you can glow a bit. And let the job take care of itself. If you are good, a job will find you. If you strive all the time for immediate advancement, you’re bound to get disappointed somewhere along the road.

You really keep going. Is there still more you want to do? Are there things you still want to achieve?

Henry Kissinger: I work all the time. Now, not for financial reasons, but because I do things I want to do. So I’m writing a book right now and of course I want to finish that. And there are various international issues in which I get involved. But I have no specific ambition. I’ll be 94 at my next birthday. So I don’t have to fill an indefinite number of years.

Thank you for speaking with us today.