We have a fear all the time. But that's what keeps us going, that's what keeps us focused. People who say 'I have no fear. I'm not afraid of ever failing,' are kidding themselves. It's the fear of failure, of not wanting to fail, that makes people as great as they are. I know that's what pushes me.

Henry Kravis was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma. His father was an oil engineer and onetime oil business partner of Joseph P. Kennedy, father of President John F. Kennedy. Young Henry attended prep school in the East, and went to Claremont College in California, where he majored in economics and was captain of the golf team.

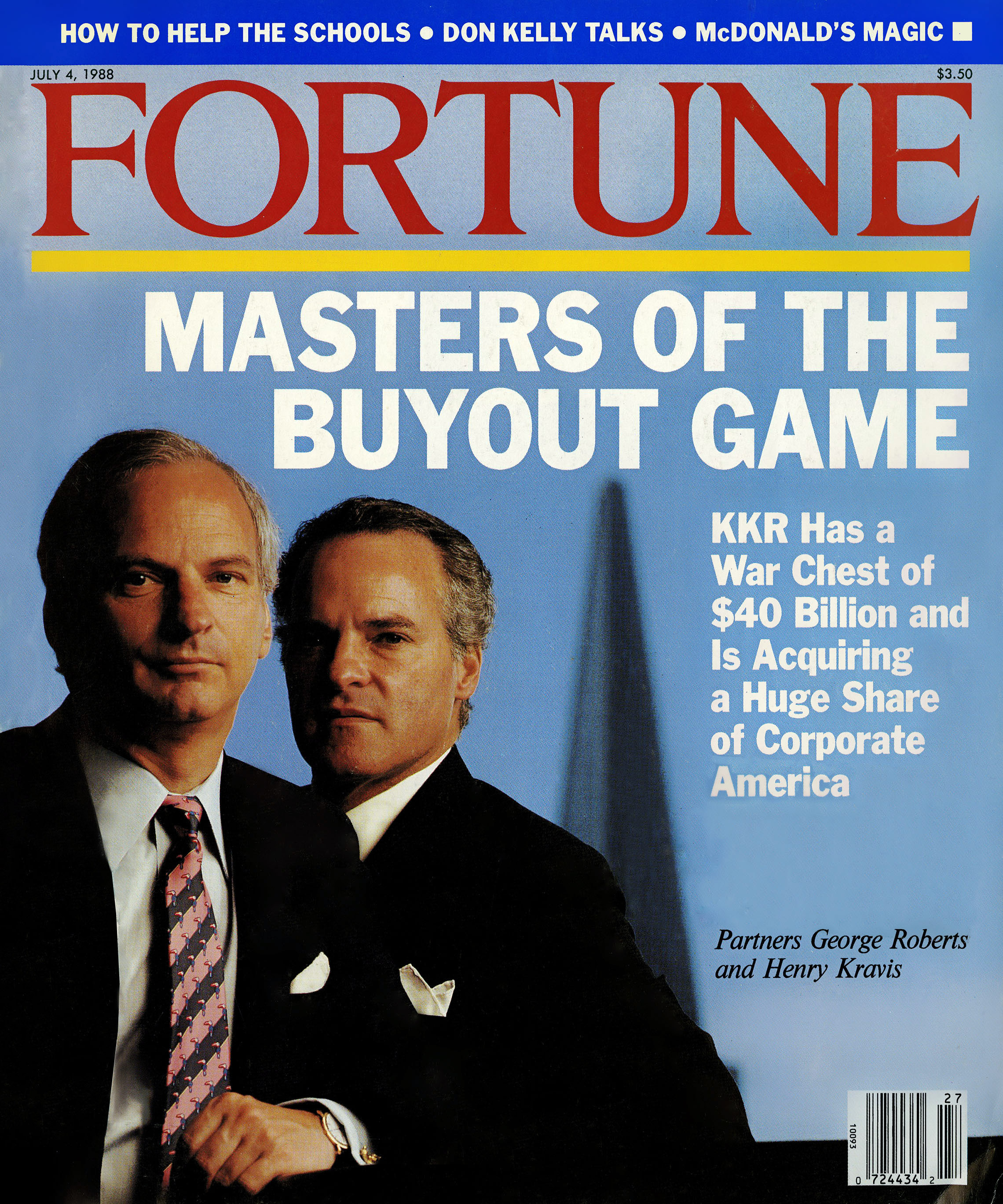

In 1969, Kravis received an MBA from Columbia University and joined the staff of Bear Stearns, along with his cousin George R. Roberts. Both young men worked under Jerome Kohlberg, Jr., the corporate finance manager. Kohlberg taught them what he called “bootstrap” acquisition. He sought out undervalued small companies, or undervalued operations within larger companies, and helped the management of these concerns borrow the capital to buy the businesses themselves. Kohlberg saw great opportunities he felt the investment banking community were overlooking. In 1976, when Bear Stearns would not appropriate the funds for these projects, Kohlberg resigned and took his two young associates with him. Together they founded the investment banking firm Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. (KKR).

For the next six years, KKR created a series of limited partnerships to acquire companies, reorganize them, sell off some assets or subsidiaries, and resell the companies. Typically, KKR put up ten percent of the buyout price out of its own funds, and borrowed the rest from investors by issuing so-called “junk bonds.” In the 1980s these bonds were usually underwritten by the investment bank Drexel Burnham Lambert. In some cases KKR helped company management and a group of limited partners buy up all the stock of a publicly traded company and take it private. They then sought to streamline the company through layoffs, or by disposing of unprofitable or inefficient subsidiaries. In other cases, they took the company private only long enough to make it lean and profitable and then offered its stock to the public again. A.J. Industries, Lily-Tulip and Houdaille Industries were some of the more spectacular leveraged buyouts of the late ’70s and early ’80s. Houdaille was the first major company listed on the New York Stock Exchange to be taken over in a leveraged buyout. In these years, KKR averaged $50 million a year for itself and earned a 36 percent return on investment for its limited partners.

In 1984, KKR pulled off its first billion-dollar buyout: Wometco Enterprises. In the same year, they introduced the public tender offer. The firm and its partners paid $465 million for sugar refiner Amstar and sold it in 1986 for $700 million. When takeover artist T. Boone Pickens staged a hostile takeover of Gulf Oil, KKR attempted a rescue, and offered $12 billion, but were outbid by Chevron. KKR next intervened in a struggle over Beatrice Companies, a conglomerate based on a food-processing business. KKR outbid the competitors, offered the management generous retirement packages and proceeded to dismantle the conglomerate. With most of the subsidiaries sold off, the core business remained extremely profitable and offered investors a seven-fold return on their money.

In this venture, KKR departed from their usual role of “white knight,” protecting company management from a hostile takeover. While this acquisition was not exactly hostile, it was certainly aggressive, an approach which came to be known as the bear hug acquisition. Safeway was acquired in a white knight operation. The buyout of Owens-Illinois was more ambiguous. The management favored the buyout; outside directors of the company opposed it. In 1987, Jerome Kohlberg, Jr., resigned from the firm, and Henry Kravis succeeded him as senior partner.

In 1988, KKR won a five-week bidding war to control RJR Nabisco, the 19th largest corporation in the U.S. This giant tobacco and food conglomerate owned such familiar brands as Camel, Winston and Salem cigarettes, Wheat Thins, Ritz Crackers, Oreo, Fig Newton, Del Monte vegetables, Planter’s Peanuts and LifeSavers. Kravis and his group bought the tobacco and food company for $25 billion, nearly double the previous record sale price of a commercial enterprise.

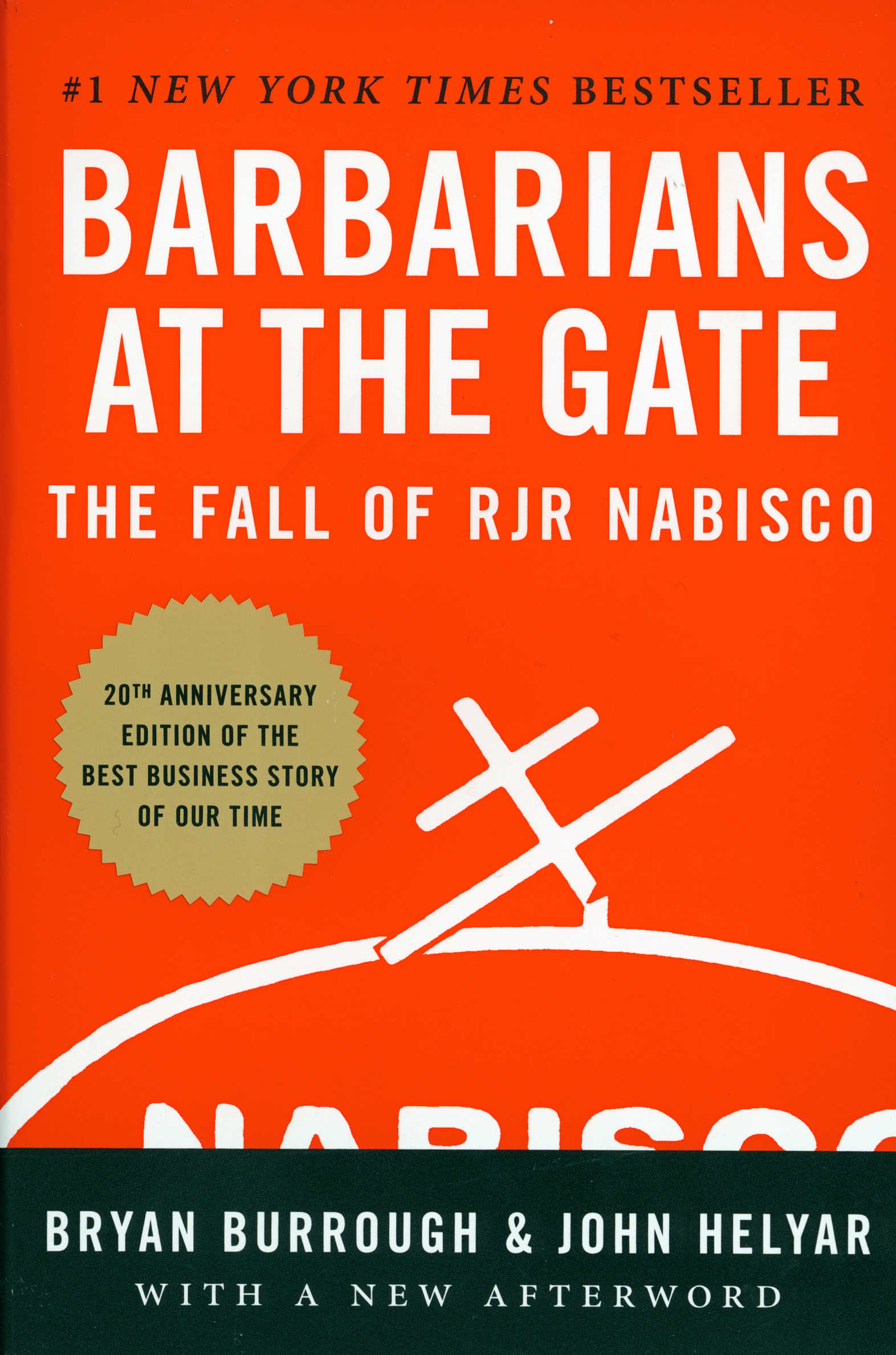

This struggle for control of RJR Nabisco captured the public imagination to an unprecedented degree. The story was dramatized in a best-selling book Barbarians at the Gate, which also became the basis of a well-received television film. In the same year as the Nabisco buyout, KKR successfully shielded Texaco from a hostile takeover, purchased the Stop and Shop grocery chain and bought the Duracell battery company from Kraft Foods.

Kravis exceeded his own record with the 2007 acquisition of energy supplier TXU Corp., now known as Energy Future Holdings. Published calculations of the cost of the deal range from 43 to 48 billion dollars, but by any estimate, it was the largest corporate buyout in history. KKR found that oil and debt didn’t necessarily mix. KKR learned that lesson the hard way after falling commodity prices doomed two of its biggest investments: the multibillion-dollar buyouts of power producer TXU Corp. and oil explorer Samson Resources Corp. KKR lost approximately $4 billion for its investors when TXU, now known as Energy Future Holdings Corp., and Samson filed for bankruptcy protection in 2014 and 2015 respectively.

Over the years, Kravis has held seats on the board of directors of Duracell, Safeway, Borden, Owens-Illinois, AutoZone, UnionTexas Petroleum, American Re-Insurance Company and First Data Corporation. In addition to his business activities, Kravis has made contributions as large as $100 million to New York’s Mount Sinai Medical Center, the Museum of Modern Art, the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He has also served as a director or trustee of the Metropolitan, the New York City Ballet, Mount Sinai Hospital, New York’s public television station (WNET), Rockefeller University, Claremont McKenna College, and Columbia Graduate School of Business. In 2010, he announced a gift of $100 million to Columbia to fund the construction of two new buildings for the Business School’s second campus, in the Manhattanville section of New York City. It is the largest donation in the school’s history.

In 2010, KKR became a publicly-traded company while exploring investments in clean energy and offering stock options to the blue-collar workers of the companies in its portfolio. On October 11, 2021, KKR announced co-founders Henry Kravis and George Roberts are stepping down as co-chief executive officers of KKR & Co. but will continue to serve as co-executive chairmen. Joe Bae and Scott Nuttall, who have served as the firm’s co-presidents since July 2017, assumed the roles of co-CEOs, effective immediately. Kravis and Roberts have led KKR as it developed into a global investment firm with $471 billion in assets across numerous business lines. In 2021, the firm closed a deal to buy insurance company Global Atlantic Financial Group Ltd., giving it $90 billion more to manage.

Columbia Business School opened the doors of its new buildings, the Henry R. Kravis Hall and David Geffen Hall, in January 2022. The 11-story Henry R. Kravis Hall, named for the co-founder of the private equity firm KKR, rises in front of the delicate steel-arched viaduct carrying Riverside Drive. It is separated from an eight-story structure named for the entertainment mogul David Geffen by a circle of grass, trees and benches embedded in a plaza. The ensemble joins a sleek new campus that so far includes a neuroscience research center, an arts center, and a think-tank-style building, called The Forum, devoted to academic discourse. The architecture of both buildings reinforces a social movement in business education to do good as well as make money.

“We’ve got a portfolio of companies that range all the way from hotels to television stations and cable TV companies, oil and gas, consumer products, and industrial products. If there’s anything that I want to know more about, I have the opportunity. It’s right in our portfolio. I can spend time at the factory or with the management and learn as much as I want. You can’t get bored doing that.”

Henry Kravis is one of the most successful investment bankers in history. He is famous in the business world for pioneering the leveraged buyout (or LBO), that is, borrowing money to buy a controlling interest in a given company. As managing partner of Kohlberg, Kravis, Roberts (KKR), he is responsible for the biggest corporate acquisitions in history. The list of companies Henry Kravis has bought and sold over the course of his career is a roll-call of great American brand names: Safeway, Beatrice, Borden, Playtex, Samsonite, Culligan, Texaco.

In 1988, Kravis engineered the buyout of RJR Nabisco, a struggle dramatized in the book and film Barbarians at the Gate. The purchase price, $24.88 billion, was the highest that had been paid for a commercial enterprise up to that time. In 2007 he surpassed his own record with the $45 billion acquisition of Energy Future Holdings (formerly TXU), the biggest corporate takeover in history.

In addition to his business activities, Henry Kravis is active in charitable causes as a patron of the arts, and a generous supporter of medicine and higher education. In 2010 he donated $100 million to the Columbia Graduate School of Business, by far the largest gift in its history.

How did you first become involved in corporate finance?

After I graduated from college, that summer, I was given a job at the Madison Fund, which was a closed-end mutual fund here in New York. Ed Merkle ran it. What a terrific guy he was! After I was there for about three weeks, he said, “Kid,” (they used to call me kid all the time), “I want you to go out and call on a company called Tri-State Motor Transit, in Joplin, Missouri. And I said, “That’s interesting, but who is going to go with me?” He said, “What do you mean, who is going to go with you? You are going to go by yourself. You are going to go meet with the president of this company. You are going to be there by yourself.” I said, “Well, I’ve never done this before.” He said, “Well, no better way to learn than trying it.” So, I put my questions together, and they reviewed them at the Madison Fund before I went out, and I arrive out there. A man in jeans and a t-shirt picks me up at the airport. Introduces himself, and I said, “This is the president of the company?” I knew that he was worth many millions of dollars, because I knew how much stock he owned, and I said, “I just learned a great lesson that you can’t tell a book by its cover.” I said, “What a good experience this is.” I spent the day with him. He then took me to his house for dinner that night, and the next morning I spent some more time with him, and I called back to Ed Merkle at the Madison Fund. I said, “We should start buying this stock.” What the company did was, they were in the transportation business, hauling explosives during the Vietnam War, so they were doing very well. I got lucky, and every share of stock we bought, the stock kept going higher and higher. And Merkle thought I was pretty smart.

Then he sent me out to call on a few other companies. I remember calling on Roy Disney, at Disney. That was just a great experience for me, never having met somebody like that. I had read everything that I could before I got out there and had all my questions laid out. I had really thought through what I wanted to ask and, as a result, it went very well. I then finished that summer, and was going to go to business school at Columbia, to get my master’s. I told the Madison Fund people that I was going to do this, which they knew. They wanted me to stay, but I said, “No, I’m going to go ahead and get my master’s.”

I started at Columbia and, after my first semester, I said, “I don’t know if this is really for me.” I remember being in a class, a marketing class, my first year, first semester. And the professor said, “How many of you want to work for Procter and Gamble?” And everybody’s hands went up. And I said, “Oh, my gosh, this is not for me. I’ve got to get out of here. I’m in the wrong place.” I called my dad, and I said, “I’m going to drop out, and I’m going to go back to work for the Madison Fund.” He said, “No, you’re making a mistake, son.” He says, “I think you’ve gotten the worst over. The first semester is always the hardest at business school. Stick with it. It will always be good to have your master’s.” And long story short, I did stick with it.

I asked at the Madison Fund if I couldn’t come back and work, though, for the next three semesters, while I was getting my master’s at the same time. They said fine, and I said, “I’ll have to work around my course schedule, but I’ll try to arrange my courses so that I can do more work with the Madison Fund and a little less work, maybe, at Columbia.” I did that, and I was able to call on other companies.

The Madison Fund had a company which they controlled. It was the old Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad in Denison, Texas. We set up a holding company to utilize the tax loss that was being generated by this railroad. They were abandoning track that went into cornfield, and so forth. Merkle came to me one day, and he said, “Henry, I’d like you to buy companies for Katy Industries.” I said, “Well, that’s fascinating, but I don’t know how to buy a company. I’ve never bought a company in my life.” And he said, “Look, kid, you know how to pick stocks. You buy a company the same way you buy stocks. If you don’t like it you just sell it. And that’s that.” And I thought, well, it doesn’t sound right to me, but this man has been pretty good in the stock market, he must know, and he’s a lot older than I am. So, I said, “Fine, let’s see if I can find some companies.” I thought about areas where I could buy small companies, and really build a group. It was the oil service business I picked, because there were a lot of family companies down in Louisiana in particular. I spent a lot of time in New Orleans, and found a number of companies in the surrounding areas, like Houma, Louisiana, and Berwick, Louisiana and Lake Charles. I’d sit in these people’s homes, in their kitchens sometimes, eating crayfish with them and shrimp. They’d say, “Where’s the guy with gray hair?” They assumed somebody with gray hair was going to come down. “If my company is going to be sold, I’m not going to sell it to some kid here. I’m going to sell it to some guy with gray hair.” And I said, “Well, unfortunately, it’s me. I’m the only one you get to deal with.” And so I bought a few companies. They worked out all right.

Eventually, I left the Madison Fund and Katy Industries. Then ended up at Bear Stearns, in their corporate finance department, where my cousin George Roberts was working, and also where Jerry Kohlberg was working. Jerry had bought a company. It was the first buyout that the firm had done in 1965. I started studying it, liked what I saw. George and I kept talking about it. In the late ’60s we started buying a few companies, and in the early ’70s. They were all very small companies. George, at that point, was in San Francisco with Bear Stearns, and I was in New York with Jerry. We bought probably seven or eight or nine different companies in the early ’70s, culminating in the largest acquisition that Bear Stearns did, which was in 1975. That was a company called Incom International. It was the industrial components group of companies from Rockwell. We paid $92 million to buy this company, and Bear Stearns, I remember, got the biggest fee they’d ever gotten, which in 1975 was $950,000. We decided shortly after that, George, Jerry and I decided to leave the firm. We wanted to do something on our own. Really wanted to concentrate just on management buyouts, or leveraged buyouts, which are one and the same. We said, “OK, let’s go off.” On May 1, 1976, we formed this firm, and the rest is history.

We got lucky. I think we’ve had some principles that we’ve stuck to. Very disciplined investors and very disciplined people there. And that’s what’s given us the ability to say no. It’s one of the most important things at the end of the day, being able to say no to an investment. Even if you’ve done a lot of work, work will never hurt you.

But once you buy a company, you are married. You are married to that company. It’s not like Ed Merkle said, “If you don’t like it, just sell it.” You know, you’ve got it. It’s a lot harder to sell a company than it is to buy a company. Since we formed the firm in 1976, we’ve bought some 38 different companies, and we spent about $65 billion, buying these different companies. People always call and congratulate us when we buy a company or when it’s announced. I say, “Look, don’t congratulate us when we buy a company, congratulate us when we sell it.” I said, “Any fool can overpay and buy a company, as long as money will last to buy it.” I said, “Our job really begins the day we buy the company, and we start working with the management, we start working about where this company is headed.” And make sure that capital structure we have in place is the right capital structure.

I think that’s the reason that we’ve been successful. It’s not just buying the company. Sure, we picked the right companies, we picked the right management and we’ve given them the right incentive to perform. But most importantly, we’ve had the management have the right incentives. Management has been an owner, management has had their own equity on the line. They have something at risk. I always like to refer to many managers in corporate America as the renters of the corporate assets, not the owners. “Where have the Carnegies and the Mellons and the Rockefellers gone?” A lot of them are gone. Our concept is to bring that back. To bring back that ownership. If you have something at risk, you think differently. If you go out and rent an Avis rental car, and you put a scratch on it, you are not going to be that happy, but it’s not going to really upset you that much. What you really want to do is get back to the Avis counter before they see the scratch. Whereas if you own your own car, and you put a scratch in that car, you are going to be out there polishing it, and making sure that scratch is gone. You are going to take extra special care. Exactly the same concept if you own the company, if you have your own money at risk.

You start to say, “Do we really need all those people that we have in the company? Do we need as many airplanes?” RJR Nabisco, for example. We had 81 people in the flight department when we bought the company, and they had 11 corporate jets. Today we have 24 people in the flight department, and we have four planes. We’ve got one airport, versus four airports that the company had. You think differently. I’m giving you a very long answer to what appears to be a simple question, but everything was done in steps, and everything becomes a building block. As my mother said to me on many, many occasions, “You’ve got to build the foundation first.” If you build that foundation, both the moral and the ethical foundation, as well as the business foundation, and the experience foundation, then the building won’t crumble. But if you don’t build that foundation, it’s not a solid foundation. The building will crumble.

RJR Nabisco was one of the biggest deals in the history of this country. What were you thinking about? Were you sitting around the table talking about billions of dollars. What’s going through your mind?

Henry Kravis: It’s funny. I never thought that was such a big deal when we made the offer. It wasn’t until I woke up after we bought it and thought, “That was really a big deal.” That wasn’t the issue. That isn’t how we look at things. We didn’t say, “Gee, we want to buy the biggest company in the world, so we’ve got to own this company.” No. If the company didn’t make sense, or the price didn’t make sense, or we couldn’t do the financing on the proper terms, we wouldn’t have done it. It would have been as simple as that. We had other issues on our minds.

First of all was the smoking issue. No one at KKR smoked. And so we had to wrestle with that. Did we want to own a company that was in the tobacco business? If we end up buying a company of this size, and this visibility, it had to work. Because it is under a microscope, and everybody in America is waiting for this thing to fail. And we never doubted that it would succeed. We knew that it would succeed. We wanted to make sure the capitalization of the company was proper so that if there was a hiccup in the earnings, it had a fallback.

The companies that have gotten into trouble are those that have razor-thin margin for error. Murphy’s law — something is going to go wrong. Things never work out exactly as you plan them. You’ve got to make room for the possibility that things will not be exactly as you had hoped or as you had planned. We built that into that capital structure. Visibility was a big issue with us. What did it mean to our families? What did it mean to our private life? Particularly George Roberts and myself. It was something that both of us wrestled with a lot. How was Washington going to view this? How would this be accepted by senators and congressmen? Were they going to be after us because we had made this large acquisition? We didn’t start it. It was started by the management of the company. We came in and succeeded in buying it. These were the things that went through our minds, much more than “Gee, it’s $25 billion.” We said, “Because it’s $25 billion, and because we are borrowing $14 billion from the banks in bank debt, then if this fails, we don’t want to be the ones known to have brought down the banking system. We have to make this work.”

On that day, at that moment, when the bid was accepted, when the deal was closed, how did you feel?

Henry Kravis: There really were two days, two points in time that were very important. One was the day after a very long, long day and all night we had been up. We thought we had an agreed-upon deal. The other group came back and started raising their bid. That threw the board of directors into turmoil. They spent from eight in the morning until seven that night debating. Did they want to take Ross Johnson/Shearson’s offer, or did they want to take the KKR offer? I felt enormous relief when they came out and said, “All right. You won.” They’d come out earlier and said, “We will pay you an enormous fee (I think it was something like 250 million dollars) to give us two more weeks to decide who to pick.” We didn’t blink an eye. We said, “Absolutely not. You’ve got until today and that is it. We want to own this company. We are not in it for the fee business. We are in it because we want to own this company. We are not giving you any more time at all.” That was all documented in Barbarians at the Gate. In hindsight, we stuck to our principles. We are in the business of buying companies and owning the equity, and putting our own money up, and making the company better. That’s the opportunity we wanted. We stuck to it, and we ended up being successful in buying the company. I felt great relief and great excitement for our whole team, because this firm was brought so much closer together. Our advisors were brought much closer together with us. Particularly Dick Beattie, who was our lead counsel. He’s the chairman of Simpson, Thatcher, and Bartlett, and just a wonderful human being. And that was great pleasure for us. Our accountants lived with us, from Deloitte, Haskins and Sells. So that was all great excitement and relief. The second time was the day that the tender offer was actually accepted and we had enough shares in, and we actually took control of the company.

I guess there was a third period, which was in between, which was the day that the bank financing had to be in, and we were concerned. Would we get enough bank financing? I had gone all over the world. I was in Europe, and I had been in Japan, and in the States with a couple of my associates, raising this bank financing. And it was the day that that had to come in, and we had large amounts of commitments coming in. And we far exceeded what we had thought, and that was a great revelation. Because if we didn’t get that, we didn’t know what we were going to do. We went to every bank in the world practically of size.