Just do it. Just pick up a camera and start shooting something.

James Cameron was born in Kapuskasing, in Northern Ontario, Canada. Chafing at the strict discipline of his engineer father, Cameron became the master builder of his playmates, and enlisted his friends in elaborate construction projects, building go-carts, boats, rockets, catapults and miniature submersibles. His artist mother encouraged him to draw and paint. She helped arrange an exhibition of his work in a local gallery when he was still in his teens. Inspired by the film 2001: A Space Odyssey, he began to experiment with 16-mm film, photographing model space ships he had built.

The Cameron family moved to Fullerton, California when he was 17 and Cameron enrolled at Fullerton College. Uncertain of his direction in life, torn between art and science, he dropped out of college, married a waitress and drove a truck for the local school district. After the film Star Wars reawakened his love of filmmaking, he quit his job and followed his own course of study in the library of the University of Southern California, reading up on the technology of special effects, optical printing, front and rear projection. He spent his meager savings on photographic equipment, building his own dolly track and experimenting with beam splitters in the living room of his small suburban house.

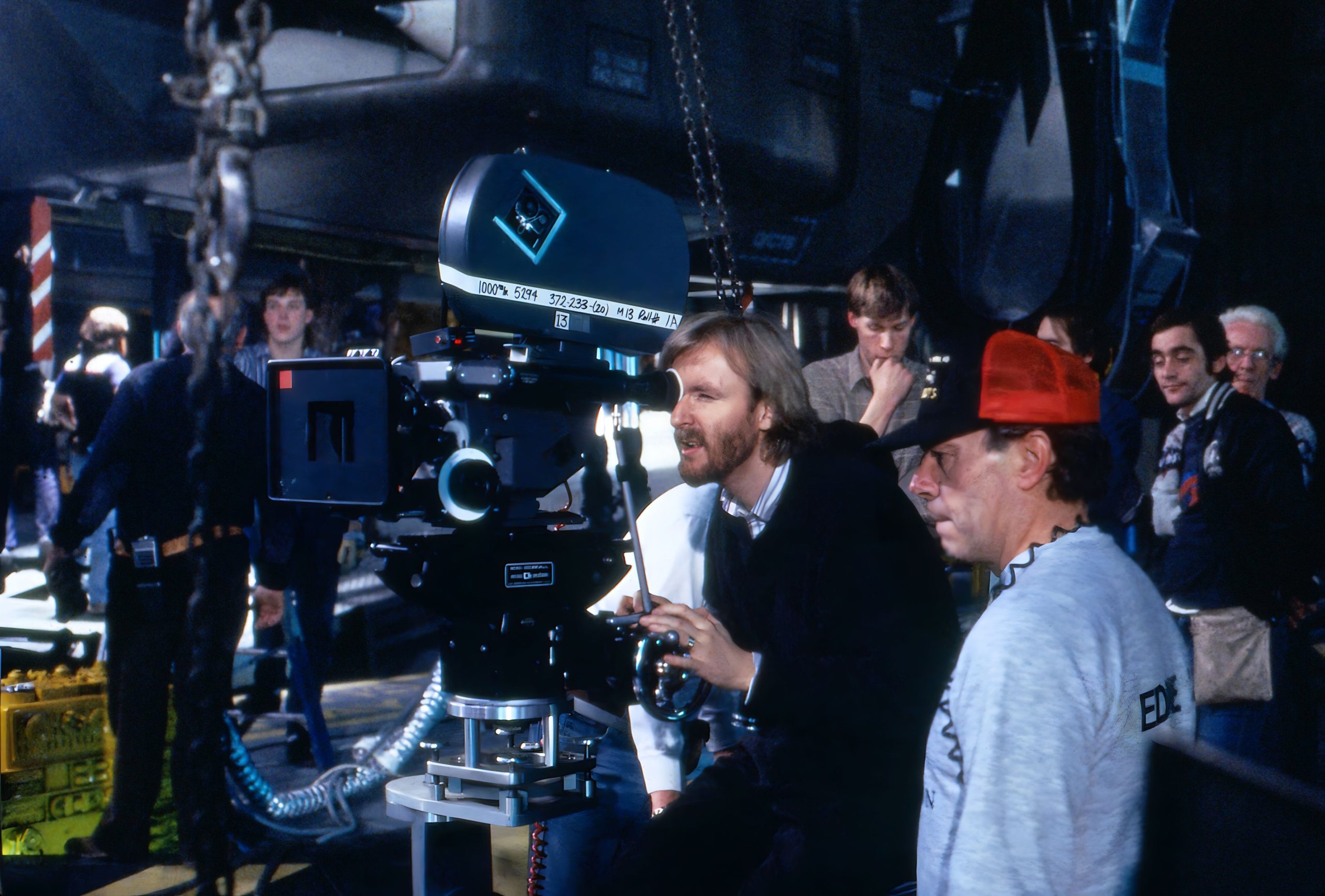

His wife and friends doubted his sanity, but he borrowed money from friends to make a short film he showed to low-budget maestro Roger Corman. Corman gave Cameron a chance to work as a model builder and production designer on his horror films. “Three weeks after I started I had my own department,” Cameron told Premiere magazine. “I was hiring people, and everybody else that worked there just hated me.”

After two years with Corman, Cameron got his first crack at directing, but it almost turned into his last. The producer of Piranha II: The Spawning fired him unceremoniously, claiming the footage Cameron had shot was unusable. Cameron followed the producer from Jamaica to Rome, let himself into the editing bay after it was closed, and re-cut sections of the film himself.

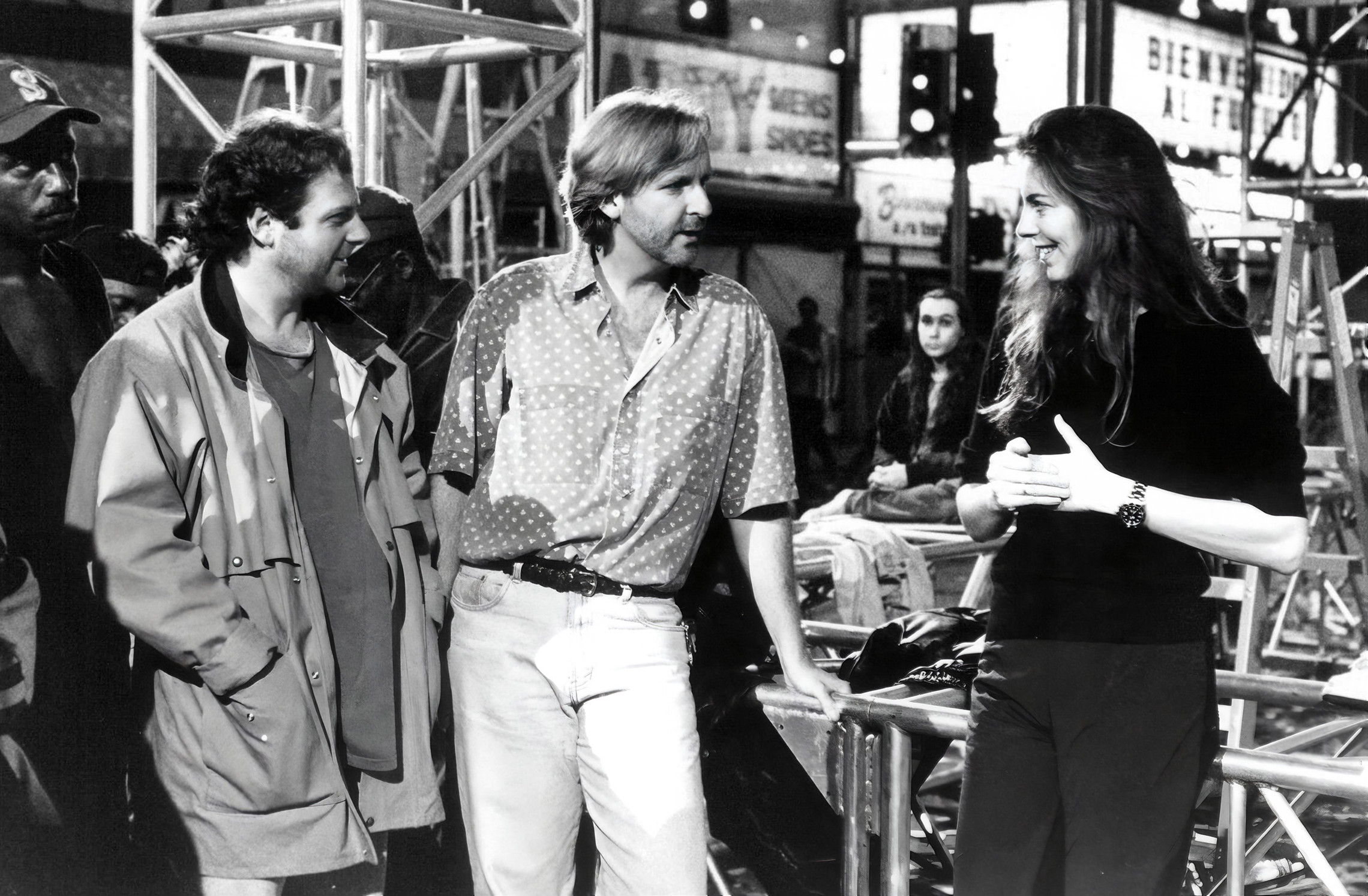

While in Rome he conceived the film that was to make his reputation, The Terminator. The script found takers at the major studios, but Cameron insisted on directing it himself, a deal-killer. He finally sold the rights to producer Gale Anne Hurd for one dollar, on condition that he direct it himself. Cameron’s unbridled enthusiasm won over Hemdale Films head John Daly and star Arnold Schwarzenegger. While waiting for Schwarzenegger to become available, Cameron wrote screenplays for Rambo: First Blood Part II and Aliens.

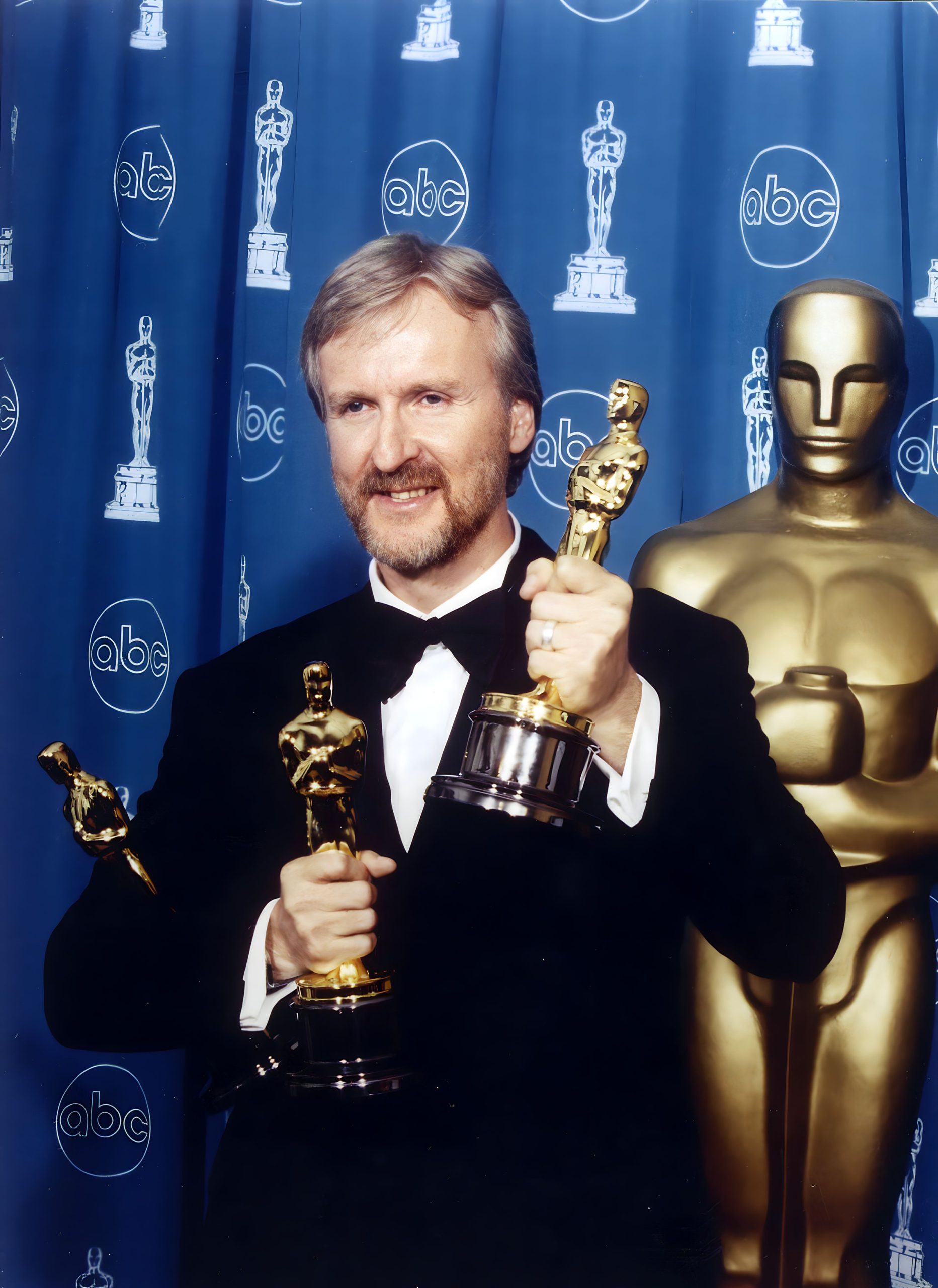

With the international success of The Terminator, Cameron won the director’s chair for Aliens and went on to direct The Abyss, Terminator 2: Judgment Day and True Lies. Typecast as a director of high-testosterone action films, Cameron raised eyebrows by proposing Titanic as an intimate love story, albeit one with mind-boggling special effects. As production of the film ran months over schedule and millions of dollars over budget, industry pundits predicted an ignominious disaster. Cameron proved them wrong when Titanic broke box office records all over the world and swept the Academy Awards, winning an unprecedented 11 Oscars, including statuettes for Cameron as Best Director, and for the film as Best Picture.

Cameron’s reputation as a driven perfectionist has become part of Hollywood legend, but he takes it in stride as he calmly plans each film. In 2009, he unveiled his most ambitious project of all: Avatar, a science fiction epic, four years in the making. Based on a script Cameron first wrote in 1994, Avatar was the first big budget action film to be shot in 3D, using innovative camera technology Cameron developed himself. The revolutionary film earned over $1 billion in its first three weekends. Released simultaneously in IMAX, as well as 3D and conventional widescreen presentation, it immediately broke box office records in all formats. Within a few months of its release, Avatar‘s box office receipts exceeded those of every other film ever made, including the previous box office champion, James Cameron’s Titanic.

The success of Cameron’s films has enabled him to pursue a wealth of other interests, including deep-sea exploration. An Explorer-in-Residence of the National Geographic Society (NGS), he helped found the Deepsea Challenge project, in partnership with the NGS. As part of the project, Cameron himself has undertaken a record-setting voyage to the deepest place on Earth.

Cameron made his journey in a custom-designed submarine, the Deepsea Challenger, described as a “vertical torpedo,” loaded with 3D cameras, powerful lights and a hydraulic robot arm. After testing the sub in the New Britain Trench, off Papua New Guinea, Cameron headed for the Mariana Trench, in the Western Pacific, east of the Mariana Islands, and south of Guam, where the Pacific tectonic plate subsides beneath the Mariana plate to its west. The Challenger Deep is the lowest point in the Trench, a narrow canyon, lying an estimated 6.78 miles (35,800 ft. or 10.91 kilometers) below sea level, although some data suggest it may go deeper still.

On March 25, 2012, Cameron descended, alone, traveling for over two hours from the dazzling light of the Equator to the chilling darkness of the Deep. Driving across the ocean floor for nearly three hours, Cameron explored a desolate landscape, almost as barren as the moon. In the New Britain Trench, he had encountered large amoeba-like jellyfish and anemones, but Cameron found little animal life in the Deep other than inch-long, shrimp-like amphipods. Although a failure of the hydraulic system prevented him from collecting samples and capturing as many images as he hoped on this initial voyage, the technology of the Challenger vehicle proved effective enough to enable return trips to the Deep. Future expeditions will collect soil samples whose microbial life could yield significant information on the origins of life on earth, and the possibility of life on other planets.

The year 2012 marked a milestone for Cameron the filmmaker as well, the long-awaited release of a 3D edition of his 1997 classic Titanic. Whatever future surprises James Cameron has up his sleeve, his exploits as filmmaker and explorer have already touched the lives of millions.

In January 2023, the long-awaited Avatar sequel, Avatar: The Way Of Water, surpassed $2 billion on a budget of $350-460 million—making James Cameron the only director to have three films top $2 billion at the worldwide box office. Cameron’s other two films include the original Avatar (2009), which is number one of all time, with $2.923 billion on a $237 million budget, and Titanic (1997), with 2.195 billion on a budget of $200 million.

In December 2025, Cameron released Avatar: Fire and Ash, the third film in his groundbreaking Avatar series, continuing his long-standing pursuit of technological innovation and large-scale cinematic storytelling. The film arrived amid global anticipation and further expanded the world of Pandora, reinforcing the franchise’s central place in modern film history. Just days before the film’s theatrical release, Forbes reported that James Cameron had officially become a billionaire. Beginning with The Terminator and Aliens, and extending through Titanic and the first three Avatar films, Cameron’s movies have earned nearly $9 billion at the worldwide box office. Forbes estimated his personal net worth at approximately $1.1 billion, placing him among a small group of filmmakers whose careers have achieved both extraordinary creative impact and unparalleled commercial success.

“Everyone around me had basically said, ‘You stink. You suck. You don’t know what you’re doing.'”

James Cameron was out of luck. After working for years as a model builder, production designer and second-unit director on low-budget horror films, he had been fired from his first job as director in a feature film. Stranded in Rome, swiping rolls off of room service carts, he had hit bottom. But he had an idea for another film; that idea became The Terminator. The script was easy to sell, but no studio wanted to take a chance on Cameron as director. His unbridled enthusiasm won over a few brave producers and star Arnold Schwarzenegger. The film was a runaway international hit and Cameron was on his way.

Aliens and True Lies consolidated Cameron’s reputation as a director of action films, but he wanted more. Cameron’s Titanic went on to become the first motion picture to gross more than $1 billion worldwide and also earned an unprecedented 11 Academy Awards, including Oscars for Director, Cinematography, Film Editing and Best Picture. It became the top-grossing motion picture of all time, until it was surpassed by Cameron’s Avatar, a breathtaking science fiction spectacle photographed in a revolutionary 3D process invented by the director himself. With these historic achievements in motion picture production, Cameron has become, in the words of Titanic‘s Jack, “King of the World.”

A lot of people ask me, you know, “What’s the best advice to someone who wants to be a director?” And the answer I give is very simple: “Be a director.” Pick up a camera. Shoot something. No matter how small, no matter how cheesy, no matter whether your friends and your sister star in it. Put your name on it as director. Now you’re a director. Everything after that you’re just negotiating your budget and your fee. So it’s a state of mind is really the point, once you commit yourself to do it.

Then the hard part starts. You have to foreswear all other paths, because you can’t keep a foot in cabinet-making and a foot in directing. You can’t keep one foot in another job. It’s a total and all-consuming thing. I suspect that’s true of many of the difficult and challenging things in the world, whether it’s research or whatever. Certainly the arts must be all-consuming, because you’re in competition with people who have made that decision, who have committed themselves 100 percent. You’re competing for resources. It’s a big coral reef. It’s a big food chain, and you’re competing for resources, and you’re competing against people who have made that commitment. If you don’t make the same commitment you’re not going to compete. It’s that simple.

How did you get your first opportunity to direct as a professional?

James Cameron: You never really “get” an opportunity. You take an opportunity. You know, in the filmmaking business no one ever gives you anything. Nobody ever taps you on the shoulder and says, “You know, I’ve really admired the way you talk and the way you draw, and I think you’d make a good director.” It doesn’t happen that way. You have to constantly be pulling on somebody’s sleeve saying, “Hey, I want to direct. I want to direct. I want to direct.” And you have to be willing to make sacrifices to do that. The mistake a lot of people, I think, make in Hollywood is that they think, “Well, I’ll get to the top of my field as a whatever, editor, production designer, writer, and then I’ll just move laterally into directing and I’ll be more respected and I’ll have more power.” It doesn’t work that way, because you drop right to the bottom of the pack as a director.

You have to work your way up again.

The way I did it was I came in through production design, which is good because you’re thinking visually, and you’re very aware of the director’s problems in trying to tell a story, and how the environment is, you know, a manifestation of the narrative in some way. And you know, I sort of proved myself as a production designer in the scrappy, stay-all-night-for-15-days-in-a-row kind of independent filmmaking that was done at Roger Corman’s place. This was in the early ’80s. And when they see that you have the creativity and the stamina, and that you basically understand filmmaking, it’s not a ridiculous leap in that environment to say, “I now want to try my hand. I want to direct.”

I just basically went up to Roger one day and said, “I’d like to direct second unit on this.” — the film that we were making at the time, which was a low budget science fiction horror picture. And he gave me a camera and a couple, two or three people, and we started a little second unit, and the second unit basically became this steam roller that wound up shooting about a third of the picture because they were falling way behind on first unit. So they’d give me the actors and say, “Well, do scene 28 and scene 42.” And all of a sudden I was working with actors, and that was terrifying because I hadn’t really thought that part through yet. You know, that in order to direct, you have to work with actors. It’s not just about sets and visual effects. So it was simultaneously a shock and a joyful discovery because I found that all actors really want is some sense of what a writer can bring to the moment, some sense of a narrative purpose. “What am I doing? What am I trying to do here? What’s the scene about?” And it’s really pretty much that simple. So that was the next epiphany if you will, which is: this part of it is fun too.

The part I didn’t expect to be fun, the part I didn’t expect to be good at, turned out to be in a way the most fascinating part. I wouldn’t say I was good at it right away.

It took me a long time to realize that you have to have a bit of an interlanguage with actors. You have to give them something that they can act with. You can’t tell them a lot of abstract information about how their character is going to pay off in this big narrative ellipse that happens in scene 89. That doesn’t help them. You know, they’re in a room. They have to create an emotional truth in a moment and, you know, they have to be able to create that very quickly. So they need real tangible stuff and that’s a learned art, I think. But coming from writing, and understanding what they’re feeling and what they’re thinking, what the character is feeling and thinking, and having thought about it a lot for months in advance is the way that I get enough respect from the actors that they trust what I’m saying. They trust what I’m giving them to do.

We’ve read that you were fired from your first film as a director. Is it true that you had to break into the editing room in order to realize your vision of what a film should be?

James Cameron: I suppose I should clarify that. Here was a critical juncture for me. I was hired to direct a film called Piranha II. I was hired by a very unscrupulous producer who worked out of Italy. He put me with an Italian crew who spoke no English, even though I was assured that they would all speak English. I actually had to learn some Italian very quickly, I’m talking about in two weeks. That’s all the prep time I had, because I was actually replacing someone else. I was put into an untenable situation and then fired a couple of weeks into the shoot, and the producer took over directing. It turns out that he had actually done that twice before on his two previous films. That was his modus operandi, in order to get the financing and then axe the director.

In the course of throwing me off the movie, he never showed me a foot of the film that I had shot. He held on to the dailies. We were shooting in Jamaica and the dailies would go to New York and be processed. He’d fly to New York and look at them and not send them back for me to see so I wasn’t even seeing my own film. He came in and said, “Your stuff doesn’t work, doesn’t cut together. It’s a pile of junk and you’re off the movie,” and then he took over the film. And I thought, “Maybe I’m just bad. Maybe I’m just not good.”

A couple of months later I went to Rome to find out what really happened, and he wouldn’t show me any of the film. I had been in Rome prepping the film for a couple of weeks before we went to Jamaica, and I remembered the code to get in. So I went in and ran the film for myself. It wasn’t that bad. All I wanted to know was one simple fact. Could I or could I not do this job? So I made a few changes before I flew back. I don’t know if the editor ever noticed that I actually fixed a couple of things, but I had to know whether what they had said was true.

Everyone around me had basically said, “You stink. You suck. You don’t know what you’re doing.” And I just — and I accepted it but then a little voice kept saying, “I don’t think so. I don’t think it can be that bad. I remember doing some pretty cool stuff with the actors in this moment and that moment.” And I looked at it and it was fine. So then I thought, “You know what, I actually can do this, and I just fell in with a pack of, you know, thieves and whackos here.” But I also realized that I was going to have to get busy and create my own thing, and that nobody would hire me after that experience. Nobody would hire me and just put me on a film. I’d have to create my own thing and hang on tenaciously to that in order to be able to direct again, and that’s why I wrote The Terminator. I had many, many people trying to buy that script, but I wouldn’t sell the script to them unless I went with it as the director. Of course that was a turn-off for almost everybody, but we did find one low-budget producer who was willing to make the film. That was John Daly at Hemdale, and that’s how I got my real start.

Clearly the road to success is not a straight line. It’s a winding road.

James Cameron: The road to success is like Harold and the Purple Crayon. You draw it for yourself. You have to imagine it first, and then you have to draw it, and then you have to walk it. Some people fall into good luck. Some people have it handed to them, but I think the great majority map it out for themselves.

What about the setbacks and the frustrations and the self-doubts? How do you deal with them?

James Cameron: When you’re working in a public art form like filmmaking you don’t really need self-doubt, because if it’s bad you’re going to hear exactly what’s wrong with it, and if it’s good you’ll hear what’s good about it. There are plenty of other people who will inform you, so self-doubt is not really necessary. You can set that one aside. Just drop it out the door. What you need is a lot of confidence to stand up to the slings and arrows, the barrage of negativity.

We exist in a peer environment and when we’re on the outside and we’re trying to get in, all our peers are like us and just a bunch of friends or people with similar interests. And none of them think you’re special. They think they’re special. So very few people will give you encouragement.

It’s like that old adage “It’s not enough to succeed, your friends must also fail.” You’re not going to get a lot of tremendous encouragement from your peer group and you can’t feed on that energy. You can actually support each other in very tangible ways, but that thing of “Dude, you’ve got it, you’re going all the way,” you’re not going to hear that. And you’re certainly going to face rejection after rejection. You’re going to knock on a lot of doors and you’re going to have to prove yourself.

I think you know that going in if you’re going into the filmmaking process. You have to go in with your eyes open. That’s what it’s going to be like.

There’s a tremendous temptation to do a work-around, or to do a moral or ethical work-around or a shortcut in a lot of situations, because it’s easier and it’s just — you’re so needy to get those little breaks and so on. And I think a lot of people get sort of ethically short-circuited at that stage and they never recover, you know? Because I think a lot of people would say, “Well, you know, I’ll do what I have to do now, but then later I’ll be good.” It doesn’t work that way. You are who you are. Fortunately, I’ve managed to get where I am without — the occasional burglary aside — without having to really hurt anybody or go against my word. I think ultimately your word becomes the most important thing that you have. It’s the most important currency that you have. Having a successful film is a very important currency as well, but in the long run your word is the most important thing, and if you say you’re going to do something, you have to do it. I think that’s what saw me through on Titanic. Titanic was in some ways the roughest project that I’ve ever been involved with. And what saw me through on that was that I had a relationship with the people who were quite rightly panicking, but they never completely panicked because they knew who I was, and we always treated each other with a kind of respect. I always did what I think was the right or ethical thing throughout that. Even though it was costing me millions of dollars personally right out of my pocket to do it, I felt I had to do it or they would never trust me again on another film, and I think that that’s ultimately the most important currency that you reap from any situation.

Were there any moments of panic for you during the making of Titanic?

James Cameron: Pretty much every day, but when you’re in a leadership position you can never ever manifest that. You can never manifest the panic that you feel inside.

Titanic was a situation where I felt, I think, pretty much like the officer felt on the bridge of the ship. I could see the iceberg coming far away, but as hard as I turned that wheel there was just too much mass, too much inertia, and there was nothing I could do, but I still had to play it through. There was no way to get off. And so then, you know, you’re in this kind of situation where you feel quite doomed, and yet you still have to play by your own ethical standards, you know, no matter where it takes you. And ultimately that was the salvation, because I think if I hadn’t done that they might have panicked. They might have pulled the plug. Things would have been very different, the whole thing might have crashed and burned but it didn’t, you know. We held on. We missed the iceberg by that much.

You first established a reputation as a master of special effects, and yet this blockbuster film, Titanic, you call a love story. It certainly has special effects, but that’s not how you talk about it.

James Cameron: Right. Titanic was conceived as a love story, and if I could have done it without one visual effect I would have been more than happy to do that. The fact is that the ship hasn’t existed since 1912, at least not at the surface, so we had to create it somehow. Obviously it was a big visual effect show when all was said and done, but that wasn’t my motivation to make the film. I don’t think that should ever be the motivation to make a film; it should be a means to an end. Certainly there’s an aspect of me that likes big challenges, whether it’s big physical construction or visual effects or whatever. I think that’s what I do best. Other people work at a much more intimate level; they do that solely and are better at that. I think that it was definitely a goal of Titanic to integrate a very personal, very emotional, and very intimate filmmaking style with spectacle. And try to make that not be kind of chocolate syrup on a cheeseburger, you know. Make it somehow work together. I think the spectacle got people’s attention, got them to the theaters, and then the emotional, cathartic experience of watching the film is what made the film work. I think the spectacle served it but was not the defining factor in its success. Once again I think it’s a question of balance. It’s sort of like looking at a painting and saying what part of the painting is the part that makes you like it. It’s all of it working together that makes you like the painting.