What was it like growing up in small towns in the rural Mississippi and Michigan in the 1930s and ’40s?

James Earl Jones: It was very simple. Blessedly simple. I think the extent to which I have any balance at all, any mental balance, is because of being a farm kid and being raised in those isolated rural areas. Even in Mississippi there was no immediate concern about social problems, you know. We were a feudal system of our own. Grandpa was a feudal lord, and we all did our work, you know. And there were 13 of us in the household. We were self-sufficient. My grandmother though, began to prepare us in her own neurotic — and I think psychotic — way to face racism. So, she taught us to be racist, which is something I had to undo later when I got to Michigan, you know.

In Michigan it was even more isolated. Nine months of snow! As much as I yearned to flee that when I was a teenager, now I yearn to get back to that simplicity. My son now appreciates that. He’s 13. He prefers to be in the country.

What ideas, values or experiences did you bring with you from the rural South, or from rural Michigan, that helped you in college and in your career?

James Earl Jones: There’s one I’ve tried to express before about contentment. I run counter to the Constitution, which allows for the pursuit of happiness. Well, happiness is kind of something giddy. And from my people, the concept of contentment was what you were after, not to keep up with the Joneses, not to be driven. I mean the idea of lying under a palm tree and letting the banana fall in your mouth, there’s nothing wrong with that, you know, and if a wave came up too high, you rolled up the hill, you know. And I’m not saying the virtue of laziness, but the virtue of being easy on yourself. The virtue of finding an ambition that carried with it a lack of anxiety. We were self sufficient as a people, as a farm people. Even during the rationing period, during World War II, we didn’t have the anxiety that we’d starve, because we grew our own potatoes, you know? And our own hogs, and our own cows and stuff, you know. That put you at ease to a great extent. It made you responsible. We children learned responsibility automatically. We worked not because Grandpa said, “work,” we worked because if we didn’t work, the cow’s milk would go bad, the chickens would starve and stop producing eggs, and the pigs would yell a lot.

Who most influenced or inspired you?

James Earl Jones: More and more, when I single out the person out who inspired me most, I go back to my grandfather. My grandmother had the most dramatic effect on my life because she set me in one direction, and I had to go back the other direction for my sanity, and for my ability to be a social human being. But the more I think about it, the quiet one was the one I think really influenced me, because he taught me the value of being able to listen, not to rush to judgment, being really rational.

I’ll give an example. They were religious people. They allowed me to decide for myself, but they were very religious people. Protestants. When we first moved to Michigan…

Before my grandpa built his own church, we went to the neighboring town, and it was a white community. You know, up north, mostly middle European people and Indians, Chippewa Indians. We were welcome to that church, but once we got in, they didn’t know what to do with us. They didn’t know what to sing, for instance, so they sang “Ol’ Black Joe.” I mean, it’s kind of a hymn-like song I guess, it’s a Stephen Foster. Now my grandmother was immediately incensed. My grandfather said, “You know, maybe they don’t know what to do with us. Maybe they didn’t mean any harm at all. Consider that.” So it was then when I began to say, “Well maybe my grandmother isn’t always right, and maybe I should not be a rabid racist as she is recommending.” Defensive racist, you know? And maybe I should take each person as an individual.

How did you overcome these deeply-held feelings of your grandmother towards white people?

James Earl Jones: Oh, they were always available to me, but I knew she was usually not right. She was usually wrong, and it was a pleasure to see that borne out. Like being a New Yorker, you always let your paranoia serve you. It’s the same with being a minority in a so-called racist society. Nobody ever fools you, but you don’t assume that somebody’s out to get you when you meet them. I came from a world where if you saw a stranger on the road, you said, “Hi!” You waved, you honked your horn. Strangers were important people, and you didn’t get anywhere by being suspicious of them. That’s the second thing you do, not the first thing you do.

Was there anything you read as a kid that influenced or inspired you?

James Earl Jones: Reading was a big thing, yes. Books were a big thing. But the things that stick out were the newspapers. Every night before supper we’d hear Gabriel Heatter, a famous news commentator, and after supper we’d get the news from the paper. My granddad would read out loud everything that he thought was relevant and pertinent to us, and to our lives. I was influenced a great deal by what was going on in the world. We were approaching World War II at that time. Later on, when I left high school, Professor Donald Crouch, gave me a book of Emerson, Self Reliance, and he said, “Just read it when you have time, and it might be helpful.”

After the trauma of moving and not speaking, and finally speaking again, how tough was the transition to the University of Michigan?

James Earl Jones: Well, by then I’d become a verbal person again, and it was important to go on to college. My youngest uncle Randy and I were the first members of our entire family to ever go to college. I was the first to ever go in the military. So we were special, we were the vanguard. As the vanguard it was important for me to pick one of the big three professions: doctor, lawyer Indian chief. One or the other. Maybe teaching, but that was not really encouraged.

Because I thought I liked science — and I did like the Jules Verne kind of science in high school — I decided to choose medicine. And that was my rationale of going to the University of Michigan on a scholarship. It was not my favorite study, as I found out later. I was having great difficulty with physics and chemistry. So in my sophomore year, I took a senior anatomy class. I thought anatomy — being the thing that I should be most interested in — and if I could hack, as we called it, a senior class, I would continue. I didn’t hack the senior class. So in my junior year, I switched to the drama department. Also, because I was in ROTC. The Korean War was still raging, and I thought I’d be going to — if I didn’t get into a med school — I’d be off to war and probably dead the same fall. So I was determined to use my last two years in college doing something I thought I would enjoy, which was acting. And it was probably because there was girls over in the drama school too, you know?

It was always hard in those days for the university theater wing to get enough boys to match the number of girls you had in those acting classes. Boys thought it was a little sissy. You know, “Sissiness going on over there!” because the drama school is too close to the music department and the dance department.

What was your grandfather’s reaction when you said you wanted to be an actor?

James Earl Jones: Well, I never announced it. But one day, my youngest uncle — the other one who was the first to go to college, Randy — and I were sitting out on the front porch. And he was brilliant. He ended up — he just retired from Boeing Aircraft in Wichita, Kansas. And he knew he wanted to be an engineer, you know, and we would — you know, boys boasting — I couldn’t top that. So I said, “Well, I’m gonna be an actor on the stage,” and whop! from behind. My grandaddy had been listening behind the screen door. That was his way of discouraging that kind of thinking, you know. I was not only forbidden to see my father, the idea that you would really take seriously a life of a troubadour! I mean, my people were very, very simple. They were peasant people, you know? So the idea of somebody making a living as an actor or singer! You sang in church, you know, and you didn’t act at all. You tried not to act, you tried to tell the truth. The idea of being a troubadour on the road singing for your supper was very disturbing to him. So, that was his way his way of discouraging that kind of thinking.

Did his thinking change as your career progressed?

James Earl Jones: No, but his insane wife — my grandma, Maggie — hers changed. This is a woman whose bedtime stories were about lynchings and hurricanes and floods and rapes and murders. Those were her bedtime stories! For me to go into drama, that kind of turned her on a little bit. I got a job over at the little opera house in Manistee, Michigan, the county seat. We had a summer theater there. She was always the first to be there, in the front row. Wanted to see me in these dramas. So she opened the door, as far as the family was concerned, about allowing this to happen.

What was it about acting that so aroused your passion and commitment?

James Earl Jones: It wasn’t acting. It was language. It was speech. It was the thing that I’d been denied all those years and had denied myself all those years. I now had a great — an abnormal — appreciation for it, you know. And it was the idea that you can do a play — like a Shakespeare play, or any well-written play, Arthur Miller, whatever — and say things you could never imagine saying, never imagine thinking in your own life. You could say these things! That’s what it’s still about, whether it’s the movies or TV or what. That what it’s still about.

When did you know this was what you wanted to do with your life? Was there a defining moment or did it just happen?

James Earl Jones: I really think I ambled through a lot of my life, or ambled from one thing to the other. I wasn’t a lazy kid. I’d gotten that, not a work ethic, but a survival ethic built into me during my youth. I knew I had to make a living, but the idea of being a plumber was not a bad thing.

When I was in New York after I left the Army, I studied for two years at the American Theater Wing, studied acting which involved dance and fencing and speech classes and history of theater, all that. I was preparing myself for the theater, and… I got a little job here and a job there, but it wasn’t going well, and I considered some time before the mid-60s that maybe I should consider something else. And I went to NYU for some vocational testing, vocational guidance. And they found that I had a talent, perhaps, in architecture. So I applied to Pratt and Parsons for that kind of training. And I was prepared to say bye-bye to acting, go on to something else, and before I joined my fall classes, I got a job out in Indiana that set me back on the track of acting.

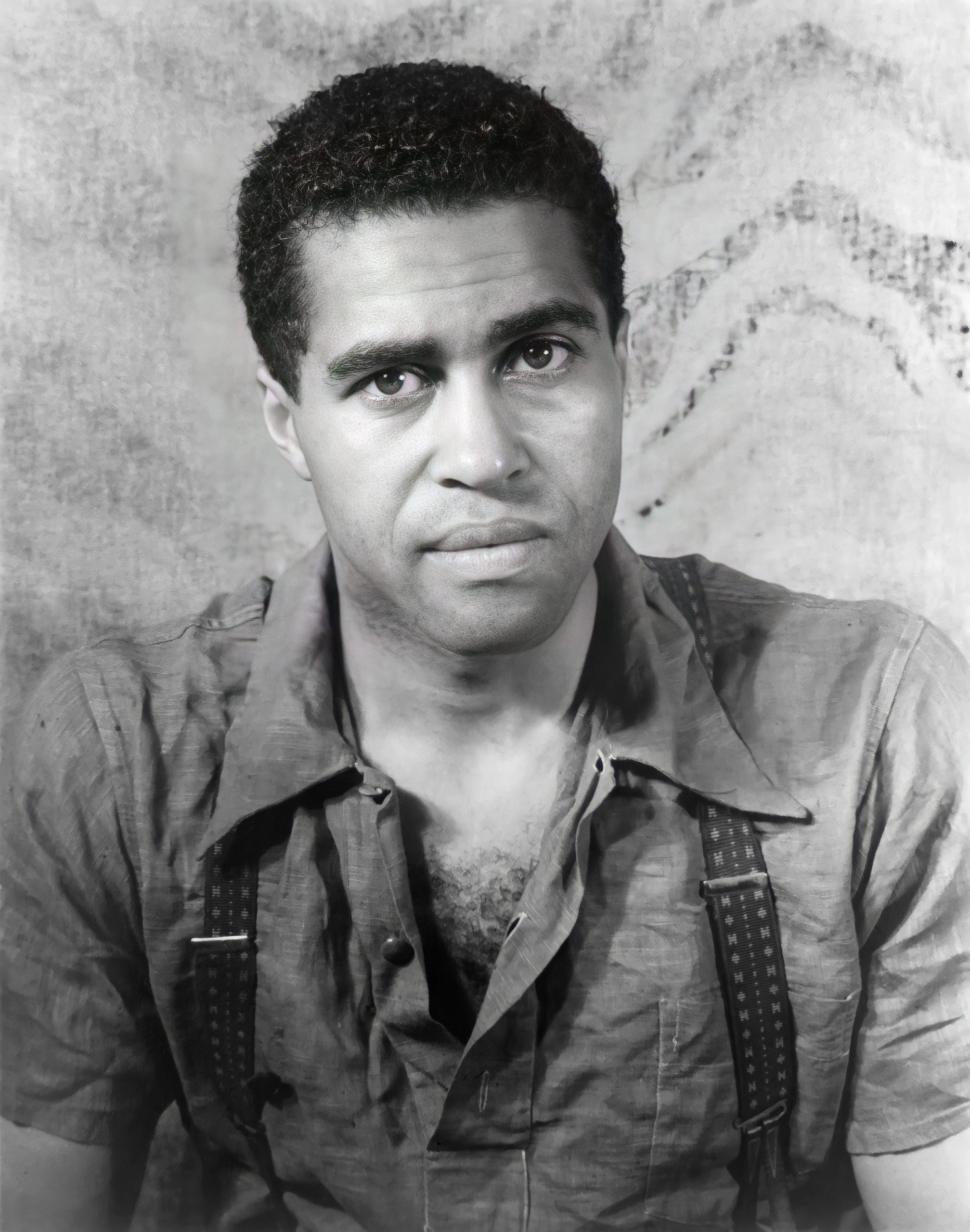

I don’t ever want to be a sentimentalist. I prefer to be a realist. I’m not a romantic really. I never approached the show business from a sentimental point of view. I never saw it as a romantic and glamorous place. I knew real show business from my father’s line. My father who had been an actor since he left the world of boxing. He was a prize fighter when he first — and a man I never really knew, a man I — allegedly I was face to face with him once when I was about two, three days old — and didn’t meet again until I was an adult, was not allowed to meet him ’til I was an adult. But, I knew of his career through his mother, and I knew he was not very successful, but I didn’t know how good an actor he was. I found out later he was quite a wonderful actor who excelled in the element of simplicity. But because he was one, black, and then blacklisted because of his involvement with labor unions and so on during those years, he just didn’t get work. Certainly not in the areas that Red Channels controlled, which was movies and taped television. He got work occasionally in theater, you know. And he told me when I finally met him, he said, “I’ve not been able to make a living at this, so I want you to know that’s a possibility; that you don’t enter it for the money. You enter it because you love doing the work.”

So I had that reality orientation. I’ve never looked at it as a romantic place, or as a place to make big bucks. Perhaps I should have. I’d have been richer if I’d gone with the bank, but I’ve applied that contentment, measure.

I was as content Off-Broadway as I was in a big Hollywood movie, and, I just try to be content wherever I am, you know. An, it doesn’t solve anything, it just makes you able to move, from one — I think I was told yesterday by some wonderful brilliant mind that I met on the path out here, Churchill said, “Success is moving from one failure to the next with undiminished enthusiasm.” Well, that’s what I was able to do from my early — so nothing threw me, really. And nothing embittered me, which is important, because I think ethnic people and women in this society can end up being embittered because of the lack of affirmative action, you know. Or the lack of removal of those ceilings, those glass ceilings. And that never happened to me, and I feel blessed. I’m a healthier person because of it. I can pass on a healthier state of mind to my son because of it.

Tell us about your relationship with your father. You sought him out in New York after all those years.

James Earl Jones: When I was finally allowed to see him. I was legally banned from seeing him until I could decide for myself. There was such animosity between those two families. It’s still unresolved. It will never be resolved with my father. I had a meeting with him just a few days ago, and it’s a mess, but I accept that. He doesn’t seem to accept it. He still wants to sort it out. He wants to place him and me and my son into some sort of galaxy. That’s a sign of romanticism, and I don’t care for it.

Family relationships come from really real bonding, not from something imagined, or a presumption about genetic inheritance. It has to be real, and I think a lot of the problems we have as a society is because we don’t acknowledge that family is important and it has to be people who are present, you know and mothers and fathers, both are not present enough with children. I’m not present enough with my son. I’m here and he’s there, you know. Often that’s the case, and that’s a problem, you know. You don’t build a bond without being present.

Could you tell us something about your struggle to become an actor in New York City?

James Earl Jones: It was as it should be. Because of my father’s orientation, I was not… I did not expect anything. No one asked me to be an actor, so no one owed me. There was no entitlement. Still is not. It is one of the — I think the arts in general, no one asked you. They might ask you to fly an airplane; they might ask you to raise wheat. But they don’t ask you to sing a song. That is still considered, in this society, one of those elitist or luxury endeavors, you know. So the idea that you are essential has not occurred yet. I think with the lack of appreciation for the National Endowment, it seems it may never occur in my time. But I think someday it must occur, because it has occurred in all great societies, all over Europe and England. The arts have always been an important ingredient to the health of a nation, but we haven’t gotten there, yet. And so actors have to accept that, you know. No one asked us. So the idea of not getting work, that’s part of the territory.

Was there someone who gave you the break you needed?

James Earl Jones: That’s hard to say. There was not some one, there was a time. I happened to happened to land in a time, in the middle ’60s, that without knowing it, and without being told by the history of theater — which we now see from a historical point of view was an explosive time. I got out of the Army — in my world — I came to New York, for instance, when the civil rights movement was just beginning, and that created a certain energy, a certain rumble, a certain impetus for black actors. And the game was not to get caught up in it, not to get swept away by it, but to keep on track of what you wanted to do. You weren’t going to the theater to change the world, but you had a chance to affect the world, the thinking and the feelings of the world.

Athol Fugard was one of the playwrights I encountered in those days. Talking about South Africa, he always said that he never assumed that he could change anybody’s mind. But he knew he could change their feelings, and their feelings would affect their minds. That’s all we can expect in terms of missionary work. I think it was more of an unusual time than any given person. And, in that time I met Athol Fugard, and so many others that helped and influenced me in the right directions.

I met the whole avant garde world, and in England it was referred to as the “angry young men” period. In Europe it was avant-garde, and we were “theater of the absurd.” Put together, you saw, internationally, theater now being available to the proletarian, that anybody could be an actor. You didn’t have to have the elite family background of the Barrymores. The door was open for Marlon Brando, you know, real common man. When Marlon did his work, when he did his Stanley Kowalski, every truck driver in New York said, “Hey, I could do that! That’s me, I could do that!” And that was very important. It was a very, very important movement, the “I can do that” movement, you know. And I was a part of that, you know. So that included women could play men’s roles, and blacks could play white roles, and truck drivers could play Marlon Brando roles. And I think that’s what sort of opened life up for me, opened up that artistic life up for me.

Why do you think you have succeeded while others have not?

James Earl Jones: Well, I know actors who, at that time, were better than I was. One in particular who was so frightened by his own talent, he would only go to auditions drunk. Self-destruction. And I think, on the other end, there were actors who were not as good as I was, perhaps who could have hung in too, but began to blame everything on race. You know? I mean they were black or whatever, minority race. And I did none of these things. I sort of stayed straight, you know, and square. Very, very square, but always able to walk straight in line, you know, toward my goal. Toward it. The goal was not really important. The goal wasn’t to be a millionaire or to be a Hollywood star. That was not the goal. The goal was something about — the goal was to find the goal, but I knew where it was. It had to do with getting on that stage and finding better and better plays — and hopefully movie scripts — to do. To be a part of good story telling. The goal was about that. And nothing threw me off, neither poverty nor discouragement. Nothing threw me off. I didn’t know Churchill’s theory then, but I lived it.

How would you explain to someone who knows nothing about acting why it’s so important to you?

James Earl Jones: Acting is not about anything romantic, not even fantasy, although you do create fantasy. It’s not about that. It’s simply very concrete. A playwright conjures a vision of a world, and he interprets that world through words. You then take those words on stage or on the screen and try to bring it alive by the interrelations between one character and another and what they say to each other. In movies it’s less important what they say; it’s how they behave. It’s about that.

So when a young man yesterday from Chapel Hill asked me — you know, he said he’s determined to be the best actor in the world — “Where do I go?” He used the phrase “dream.” He said, “I have a dream of being the best actor in the world.” And I said, “If you can turn that dream to imaging, you can image yourself, imagine yourself, and then achieving it, being able to plumb the depths of human feeling as much as Marlon Brando’s able to, and then on the other end, the technique. Find clarity and brilliance of language as much as Richard Burton did. Then you might be the best actor in the world.” But it’s doing real things. It’s nothing about fantasy.

What kind of setbacks did you meet on the road to success?

James Earl Jones: Setbacks? Yeah. There were specific ones, but it didn’t diminish my enthusiasm. Being told one day that I had a job, my first job in a TV series, the next day to going to a party and finding another young actor had the job. Somebody had lied to me. But that was the game. I’ve learned that game could be even more vicious if you let yourself feel it that way.

The idea that you’re competing with fellow human beings can get rough. My wife knows actresses who, when they go to auditions, they will deliberately distract all the other actresses. They’ll start telling stories. They’ll start asking questions deliberately, to throw you off your balance. Well, I don’t like to hear about stories like that and I certainly don’t like to — my first time on camera was with a wonderful actress named Diana Sands, and Diana began to try to tell me — my first time on camera — she began to try to tell me, “Look, you know, if you want them to use your take, then you do something to distract the other actor’s take.” I said, “You know, I don’t think I want to know that. I don’t think I want to be that busy manipulating because I came here to act, you know; and if I use all my energy manipulating, I’m not gonna do my job.” And there was something very disturbing about all that, you know. She was a brilliant actress and could do both, could manipulate as well as do her job. But, I didn’t think I could do that, you know.

How did you deal with self-doubts, with fears of failure?

James Earl Jones: Oh no, you don’t have self doubt. You don’t have fear of failure. If you do, you gotta take care of it. If the way you approach your goal is right for you, then you won’t have self doubt. Undiminished enthusiasm always stays with you.

You’re the only person who can tell whether you have talent or not, and there’s a certain point where you’ve go to be really honest with yourself and say, “Yeah, I do, and I’m going on.” or “No, I don’t.” And your parents can’t do it for you, and critics can’t do it for you. Once you’ve determined that, then there should be no room for doubt, you know. There is room that, “Well, maybe this isn’t the right role for me.” That’s always going on, you know. You’re told every day you’re not right for this role. And they might, “It’s ’cause you’re too tall.” They usually don’t know why you’re not right for it. It’s just, you didn’t ring a bell for them, that’s all. And that’s okay. You’ve got to accept the fact that you don’t ring a bell for everybody.

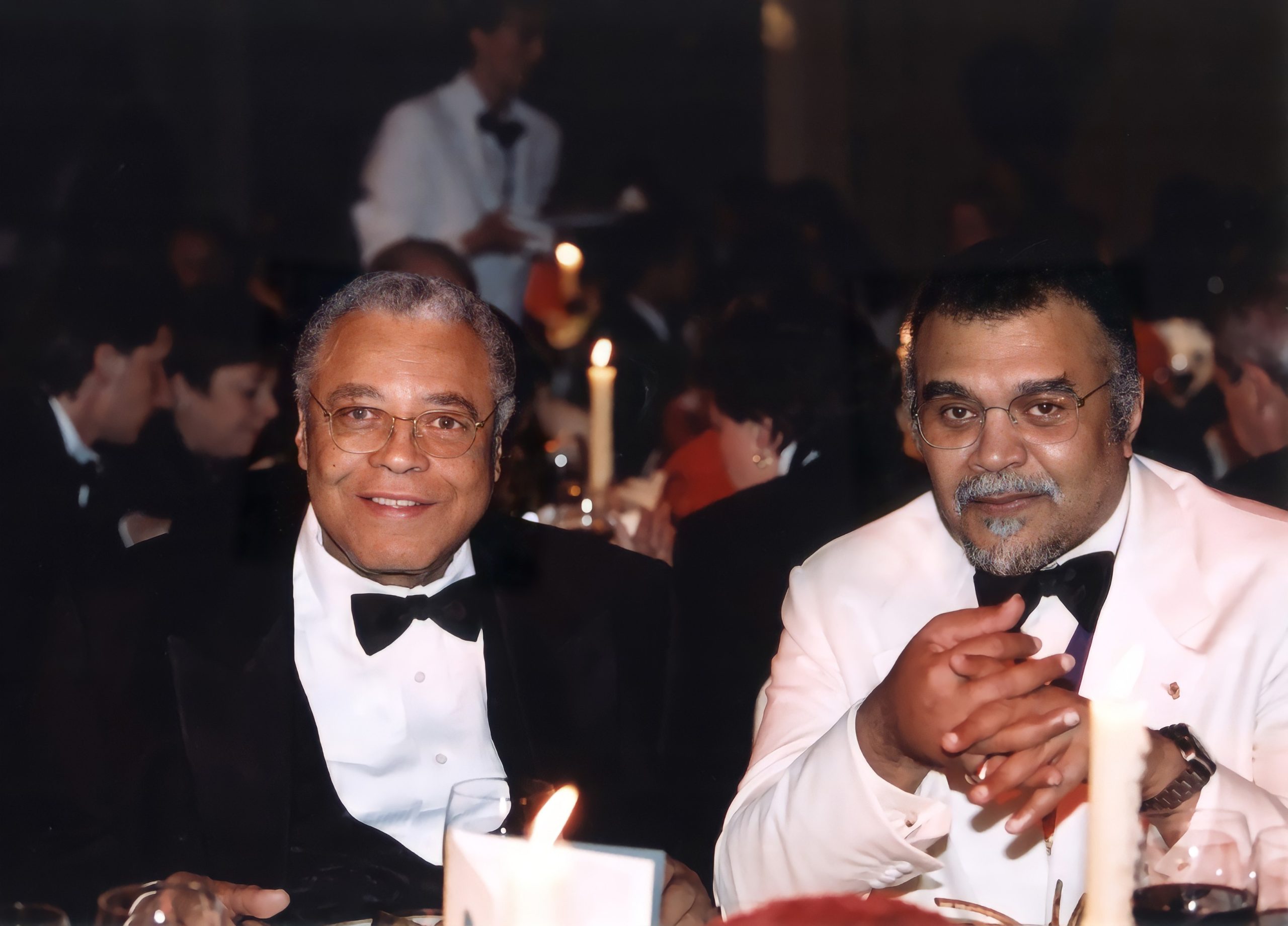

There’s only one actor I know who does: Morgan Freeman. He can ring a bell on the drama side, on the comedy side. It’s rare for this actor to miss in terms of the way he achieves his work, and it’s also rare for him to miss in his character. Whatever he does, it always seems to work in his character. That’s very rare. Most of us don’t have that going for us. We will fail to ring somebody’s bell, and that’s okay.

When I first came to the theater, I followed Sidney Poitier’s generation, which is not far ahead of mine, a couple of years. He had established the height of what young black actors could do, the rest of us were there to establish the breadth. I figured there was room for all of us: for Lou Gossett, for Raymond St. Jacques, for Godfrey Cambridge, for Billy Dee Williams. There was room for all of us, so we never felt competitive, and that was a blessing. I continued to feel that.

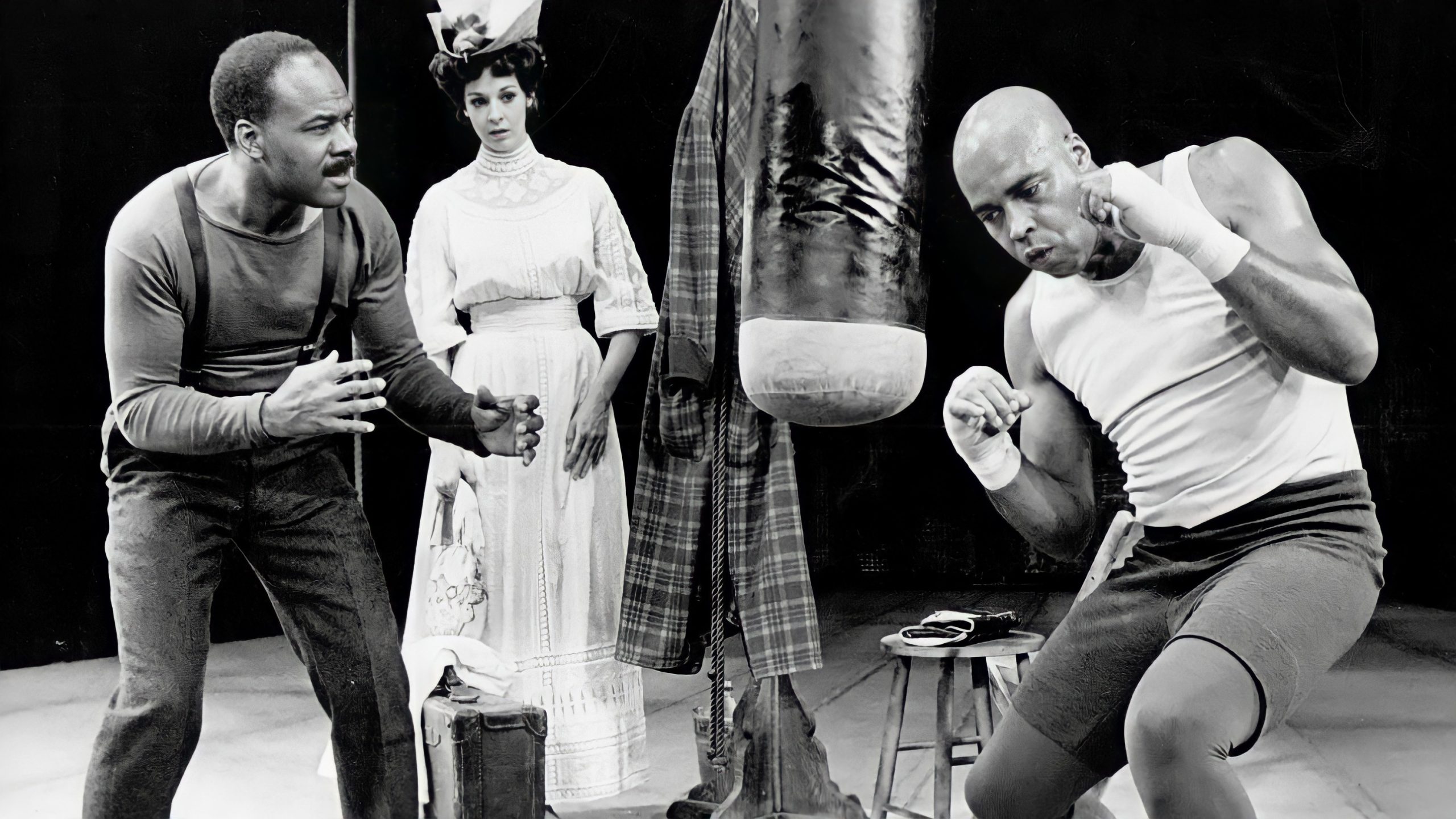

Do you see Jean Genet’s play The Blacks as a turning point in your career?

James Earl Jones: I think usually there’s the turning point that’s very public that’s acknowledged in Newsweek magazine and whatever, and then there’s those turning points that nobody notices. At first, The Blacks was one of those quiet turning points. It came to be acknowledged later on, as the production went on, year after year.

I remember meeting with the producer. She said, “James, I’m worried. Except for Roscoe Lee Brown, I don’t know whether I can gather a group of black actors who could handle this language. It wasn’t classical language but language that doesn’t have an ethnic or street twist or a rural twist. She was not sure she could find the actors would were trained vocally for that kind of speech. She was challenging me too, and I said, “Well, you might not be able to, but start with Roscoe, and I think you might.” And she did. She built a cast around Roscoe that could handle the language.

I remember Roscoe and I were referred to as “fine mummers” in one of the reviews, “There’s these two fine mummers.” But she did gather a group of actors who could handle language, and that was kind of a phenomenon. We weren’t playing sharecroppers, we weren’t playing street dudes, we were playing people of the world. It had some relevance to the movement at that time, the civil rights movement, and acknowledged the danger of racism. Genet was very clever. He wasn’t saying whites were bad and blacks were victims. He was saying any race who takes on a superior position is going to be threatened by the other race taking it on. It could flip-flop. It was an important message at the time. It’s a play that’s difficult to do now, because it tapped into the sense of America’s conscience as it existed then, and I don’t think that conscience is as healthy today as it was then. We’re too cynical for that play to work.

How do you deal with criticism? Do you react to it?

James Earl Jones: That’s a tough one, because the critic is there as an operative in that industry. He’s supposed to have a job that helps make the industry work. He’s supposed to inform people what’s worth seeing and what’s not worth seeing, according to his opinion. Or if you’re Kenneth Tynan, he’s supposed to tell you what you tried to do and how well you succeeded. And that’s very valuable. But I learned early on.

I learned early on. I think I was doing a play with J.D. Cannon, who was one of the actors in the McCloud series. And J.D. said, “Look Jimmy, we’re gonna open tomorrow night. Would you do me a favor? Don’t tell me what the critics said. I can’t handle it.” I said, “What! You can’t handle it? If they’re good can I tell you?” He said, “No. Especially when they’re good. Because whatever they say is gonna distort your ability to go on stage the next night and do the work you should do. If they say you were good, you have to try and be good. You have to try and ‘What did I do that was so good?’ And you’re distracted. If you’re bad, you’re totally defeated, or your ego’s deflated, and you’re distracted,” he says, “I’d rather not know.” And I decided at that moment that I’d do the same thing. I’d not read them anymore. I let my wife read them, and my agent read them, and if there’s something I should know, they would interpret it for me. But, I would not read that person’s opinion.

It reminded me of one of the two books we were encouraged to read. It had nothing to do with show business. One was Zen and the Art of Archery. The other was Rilke’s To a Young Poet his series of essays and letters to a poet. And…

Rilke had said to this young poet, “I sense this is what you’re doing, you’re writing for the critics. You’re writing to please the critics.” He says, “That’ll never work. Because they’re not pleasable. You must write to please yourself. And then they might be pleased, you know. But they’re secondary to what you do.” And so this all began to fall into place for me and I respect what critics do, but I don’t — their work trails mine. I mean, I’ve done my work, and I’m gonna keep looking ahead, and not behind at some reflection.

You’ve met your share of controversy in your career, in the play about Paul Robeson, even over your performance as Darth Vader. How do you deal with that?

James Earl Jones: Well the Darth Vader controversy I was able to laugh off. Raymond St. Jacques, I think, wrote a letter to the editor saying, “How dare you present the only black in the galaxy as the bad guy?” I said, “Well heck, I’m just special effects. It’s David Prowse that’s in that costume.”

I have not been able to laugh off the Paul Robeson controversy. I write about it in my book a little bit. It’s still painful. Avery Brooks now takes the same production, exact same words, and presents it to the public, and he adds the fact that he’s a singer; and it’s a glorious production. No controversy at all. In my time, Paul Robeson, Jr. had not resolved his position as guardian of his father’s image. He had not resolved it yet. We got in his way. We became a bone in his side, and so he became a bone in our side. I just happened to get in Paul Jr.’s way at the wrong time. He haunted the production and he concocted social apartheid to bring the production down. The young playwright Phillip Hayes Dean said, “He’s acting like a McCarthyite himself now.” But you know, victims of tyranny learn from the bad guys. You see it in Israel, you see it in black people. If you learn from the bad guys, you end up doing what they do.

What characteristics do you think are most important for success in any field?

James Earl Jones: I really don’t know. I ambled into this, so I didn’t record what works and what doesn’t work. I don’t know if we ever learn from history anyway. You’ve got to learn for yourself. Given that, I think every actor has to find out what works for himself. I’m hesitant to advise young actors because their world is so different from mine. How you approach an audition is very different. I think they have to dress up more, because we’re talking about image in movies more than we’re talking about the stage. I think you have to come on with an image. You have to dress the role much more than we ever thought of doing. We’d be embarrassed by that. That a brunette woman would dye her hair blond just for an audition is probably not unheard of now in a Hollywood situation. The business of training is very different now. I think you have to learn the basics.

You have to learn something more than just acting. You have to learn how to behave, how to fill your space on the stage or in film. You learn the difference also. That the film space is inner space, but you’ve got to fill it. You know, you watch Paul Newman, and he’s jam packed in a very small area of his face. All the energy that I would express in my whole body, he’s expressing right here: Zhooooom! That’s a hard one to learn for a stage actor.

What do you know about success now that you didn’t know when you were younger?

James Earl Jones: Nothing. It was not about achievement. It’s about setting on the path and going. I would’ve been a good explorer. I would’ve been good with Lewis and Clark. Cause you’re out there, and there’s nothing telling you whether you’re successful or not. There are no landmarks. You know you want to get to the Northwest corner of the country, but all you can do is walk. And there’s space and space. It must have been a wild and weird world, but I think I would have fit in very well there.

Is there something you’ve not yet had a chance to do in your career that you’d still like to do?

James Earl Jones: No. I don’t think I’ve done “the role” in film that I could say, “I leave that as my legacy.” I’ve done it on stage, but I’ve not done it in film; I’ve not found that role yet. I’d like to find it. It’s not too late. I’m still learning the art of film acting, and once I learn it, I might find it and do it before I retire. But that’s not something I need to do, that’s something I’d like to do.

Is there anything outside of acting that you’ve always wanted to do?

James Earl Jones: I want to rebuild a world similar to the one I came out of. We had the Mississippi River, and in flood time, when the flood subsided, you could walk out and see catfish in the mud puddles. I’m digging a little lake now, a three-acre lake. I want to stock it with fish. I want to rebuild that self-sufficiency that I knew as a child. That’s got nothing to do with show business.

What do you see as the greatest challenge to our society in the 21st century?

James Earl Jones: We’ve got two big ones. One is health and one is sanity. I won’t say “racism.” I say “sanity,” because racism is a form of insanity. Unfortunately, giving it a name almost sanctions it, as though we understand it. We don’t understand it. Religion becomes a part of it, and that’s insanity. Giving it a religious name almost sanctions it, and that’s wrong. We shouldn’t sanction these things, we should try to understand them. We have extreme psychotic situations that are disturbing our balance as a nation.

We have health imbalances, in the way we’ve gone about handling disease. Now there are doctors and scientists trying to find out what we did wrong with antibiotics. Where do we go from here to solve the serious health problems we’re confronting? Including drugs. It’s a health problem. To deal with it only as a crime problem won’t work. Because as long as there’s money involved, it’s going to be as much a part of the economy as oil is. So you’ve got to deal with it in a whole other way.

When my mom came with her first bid to take me into her life, I didn’t know her, because she had gone off with her new husband. They were migrant workers in the Delta region of Mississippi. They were grain harvesters, rice harvesters. In those days, large farmers would line the male workers up each morning and put a thimble full of cocaine into each shirt pocket, and the government sanctioned it, because it made them work happier and harder. I don’t think the government knew what it was doing, but at the same time, there was not a lot of addiction that came out of that period. So the addiction has to do with something psychic, mental, rather than something physical. The addiction is the despair that drives you to want to stay asleep all the time, to knock yourself out all the time. That didn’t exist then, so that cocaine itself was not addictive. So we’ve got to deal with it as a mental health as well as a physical health problem. That’s all, then we’re perfect!

What advice do you have for young people starting out today?

James Earl Jones: Carl Sandburg said, “Take no advice including this.” I think I should stop right there.

What book or play would you choose to read to your grandchildren?

James Earl Jones: My son is 13, and he used to be read to all that I need! His room is full of books. His mom did most of the reading to him. If I’m able to utter a sound when he has a child, he’d have to start pretty early. I’d like to read him some of the books we read my son. I don’t know when I’d get to a serious book, that is a book that I think would be meaningful to the child for the rest of his life.

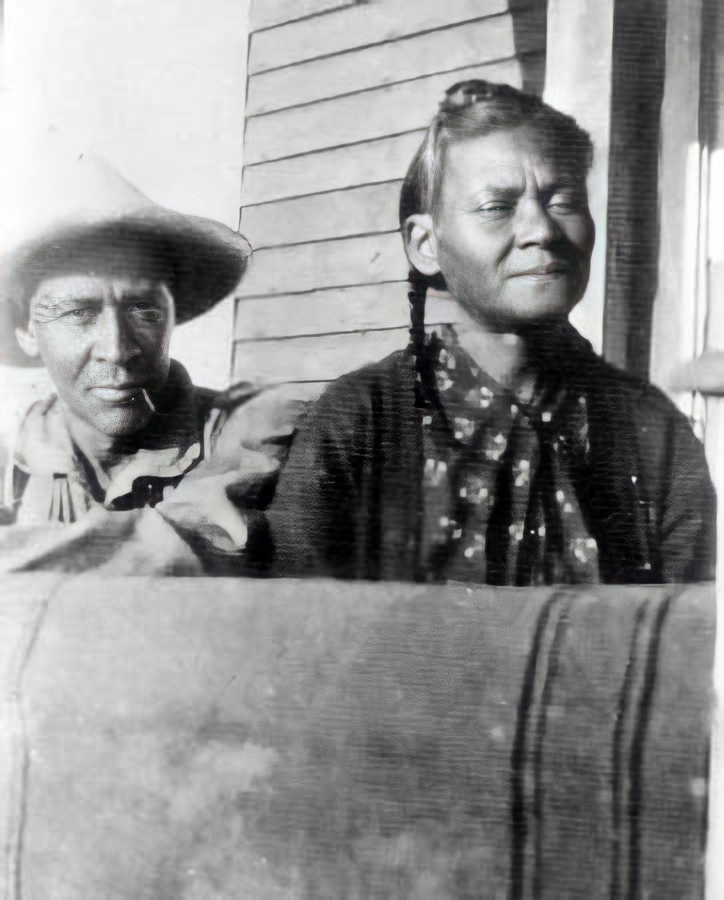

You write in your book about your Irish and Native American ancestors as well as your black ones. Was it a source of anxiety or problems when you were growing up? Did that upset you?

James Earl Jones: Why should you be upset? You are who you are. Blacks have become as racist as racist white people, and have a hard time acknowledging it. But no, we had no anxiety about having white blood in us. How could we? We all did. So what? You end up being who you are, and if you can’t come to peace with that, you’re in a lot of trouble. To deny you had Indian blood, deny you had black blood, deny you had white blood, is part of the insanity I’m talking about.

People say, “What do you do about the bombings in the churches?” What do you say? You don’t say anything. You have a response, hopefully a positive, a creative response. But the idea of talking about it? You can’t rationalize insanity. You can’t talk about it either. You lock it up. Or you treat it.

What does the American Dream mean to you?

James Earl Jones: I’m not a dreamer. I never acknowledged there was one. Each person has a place they want to get to. I just defined mine as this self-sufficient world, which is the farm. Is that the American dream? No! Most people don’t want to be on a farm. I notice that Canadians are more inclined to be that way. Every urban Canadian has the dacha, or the shack out in the woods. I don’t know if there’s an American dream. Or that you’d call it an American dream. It might be a human dream. “Dream” sounds like fantasy. I think there are problems we have to solve, if you want to call that our dream. Solutions are our dreams.

Thank you very much for speaking with us today.

You’re welcome.