That was it. I couldn’t have dreamed that I would get the opportunity to study something like a chimpanzee with no qualifications. It seemed unreal. He didn’t tell me that he wanted me because I didn’t have qualifications. He told me that later. It took over a year to find the money.

Who was going to give money to a crazy project like a young girl straight from England, no degree, going out into a potentially dangerous situation? And finally, he found some money for six months. And then the second problem, which was, I think, harder to overcome, was that in those days what we call Tanzania today was Tanganyika. It was a British protectorate, part of the British colonial empire, and the British authorities would not take responsibility for this young girl going out in the bush alone. But in the end, they said, “Well, if she brings a companion…” So who volunteered to come for four of those six months? We had money for six months. For four of those months, my same amazing mother! She packed up in England. She came out. We had so little money for this expedition, a couple of tin plates and cups. Food in tins, very little at that. One cook; we had to have somebody out there. An ex-army tent. No sewn-in groundsheet like all the fancy tents have today, just a piece of canvass on the ground and the flaps at the bottom you rolled up and tied with strings. All the centipedes and spiders and snakes could come in.

My mother was amazing, and she kept camp. I think she played two really important roles. One, she boosted my morale, because in those early days the chimpanzees ran away as soon as they saw me. They’d never seen a white ape before. They’re very conservative. They would vanish. And she would say, in the evening when I was a bit despondent, “But think what you are learning. What they’re feeding on. The kind of sized groups they travel in. How they make beds at night, bending down the branches…” all the things I’d seen through my binoculars. And so she boosted my morale. And then, secondly, she started a little clinic. She wasn’t a doctor or a nurse, but my whole family was very medical. Her brother had given her masses of simple aspirins and bandages and things like that. So she would treat the fishermen who had camped along the lake shore. And because she would spend hours with them, doing a saline drip on the tropical ulcer, she became known as a white witch doctor. And she established, for me and all my students, this great relationship with all the local people.

Before you actually went to Gombe, when Dr. Leakey was still getting the funding in order, he wanted you to go back to school. Is that right?

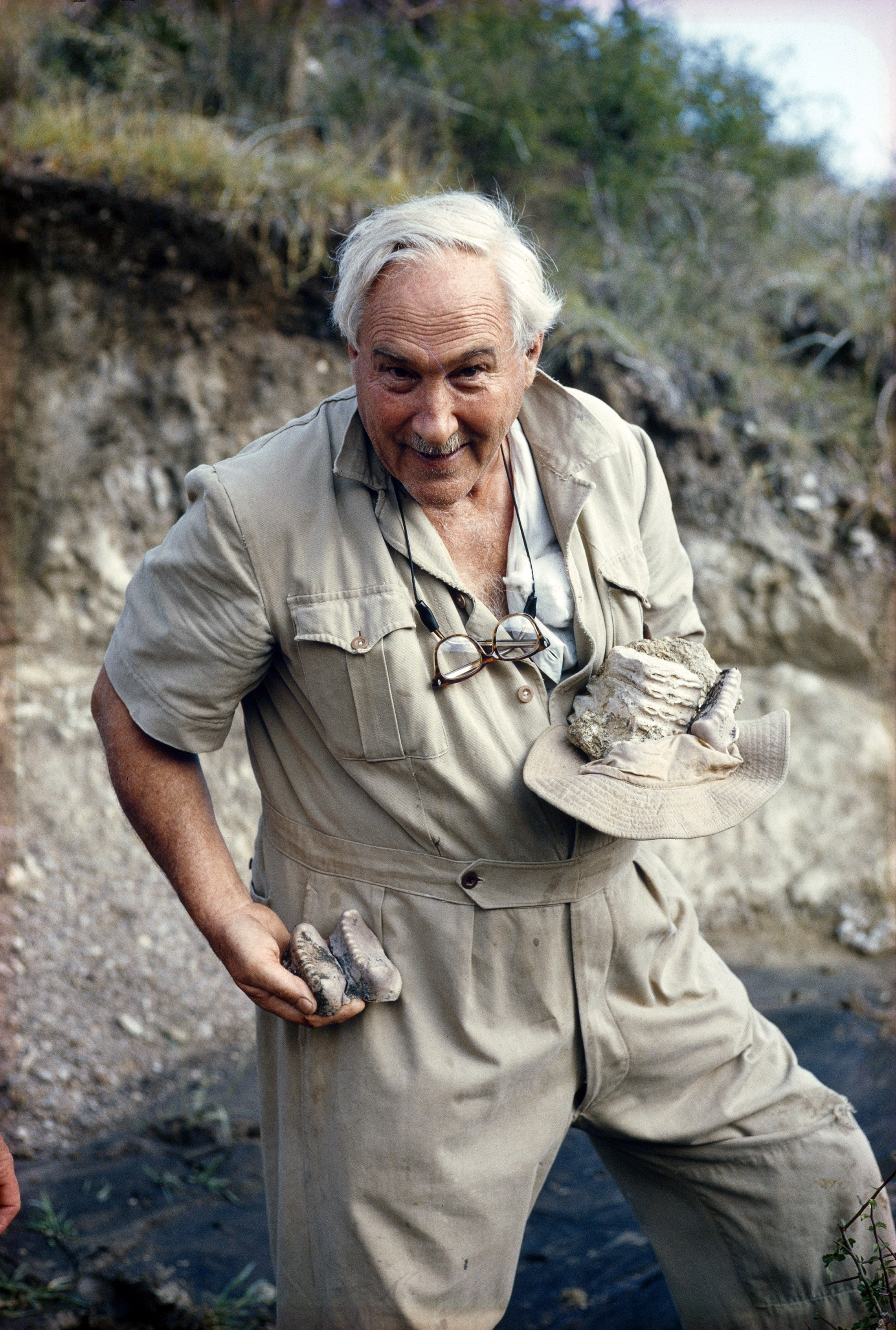

Jane Goodall: While Louis Leakey was finding the money, getting the arrangements made, getting permission, I went back to England and I worked with a very famous primatologist called John Napier, who taught me a little bit about primates, but that was just in his office. I set off ahead of my mother. So when Louis Leakey had got everything ready, I was out there helping with the last-minute arrangements, and finally all was organized.

My mother flew out to join me and we drove from Nairobi all the way to Kigoma in a short wheel base Land Rover, horribly overloaded, driven by the botanist from the museum in Nairobi. It was an amazing kind of a journey. It took three days. And when we arrived in Kigoma, it was to find that the Congo had erupted and all the refugees were coming over the lake from what was then the Belgian Congo. Then it became Zaire. Now it’s the Democratic Republic of Congo, DRC. But anyway, they were coming over Lake Tanganyika and everything was in chaos. I wasn’t allowed to go straight off to the Gombe National Park. Instead, we were stuck in Kigoma helping to feed refugees, and finally we got the permission to go.

Who was living in the Gombe Stream Reserve when you and your mother arrived?

Jane Goodall: When Mum and I set foot on the sandy beach of Gombe for that very first time, we were greeted by the headman. There wasn’t a village there. It was a couple of game scouts with their wives and kids. And then there was the headman, and he was called Idi Matata, and he had his wives, and that was it. That was that little handful of people on the beach. And Idi Matata, we found out later, was the most infamous witch doctor the area has ever known. He was supposed to have two crocodiles who were his familiars. Fortunately, he befriended me and my mother, and that made all the difference to all our relationships all around.

I remember being summoned in the middle of the night. Mum and I were summoned and somebody came over with a torch. We were taken over the stream to this little encampment on the beach. And one of his wives’ daughters had had her first baby, but it was going wrong and Mum, very wisely, didn’t touch the child ’cause she thought, “You know, if something goes wrong we’ll be blamed.” So she just kind of gave reassurance. And for some reason this girl was not… I don’t know. Maybe she was having a child out of wedlock, I don’t know. But anyway, the senior wives were not paying any attention. That’s what Mum did. She got them to come and they delivered the baby. So we could do no wrong after that. And I never forget Idi Matata, when the baby’s born, getting these really rusty scissors, holding the baby up and cutting the umbilical cord. That was about the second week we were there. What an introduction!

Was your mother really prepared for this kind of roughing it?

Jane Goodall: My mother had a pretty bad time. She never had a strong stomach. She didn’t feel well a lot of the time. She doesn’t like the heat, and it got hot. Fortunately, she left before the rainy season came, and that was when the tent leaked and everything was moldy and wet. So she was only there for four months. We arrived in July. The short rains had started, but she missed the long rain.

What was the toughest part of your study initially?

Jane Goodall: The toughest part of my study initially was getting the confidence of the chimps. So it started off, they were afraid. Then, when they began to lose their fear they became belligerent. They treated me a bit as though I was a predator, and that is very scary. I mean they’re about eight times stronger than I am. And when the big males were bristling their hair — and often it was in the rain, so they looked very black, because they feel kind of more belligerent in the rain, I guess — and shaking branches, and even sort of the ends of the branches were hitting my head. And knowing they could actually tear me to bits if they’d wanted to. And then the belligerence went away. And it was David Greybeard who really helped me get into their world, because he lost his fear. He wasn’t belligerent. He visited my camp one day to eat palm nuts. Saw some bananas lying around, took them, and then came back for more. So I would wait down in the camp instead of getting up at half past five every day. And one day David took a banana from my hand. That was just after my mother had left.

How long had you seen David Greybeard hanging around before you had this first physical contact?

Jane Goodall: It was about three weeks, four weeks after I first got to know David Greybeard in the camp. We were still putting out bananas — “we” being me and the cook, Dominique. When my mother left, she insisted Louis Leakey give me a way of communicating with the outside world. So his trusted boatmen from Lake Victoria came to join our little camp.

So I was in camp, and on this particular day I remember, can never forget, holding out a banana in my hand to David, and he came up and he was nervous. He hesitated, then he took the banana. And it was just like, you know, I imagine how the early explorers felt when they were holding out beads and things to the natives, and they were accepted for the first time. So after that, if I met a group of chimps out in the forest and they were ready to run as usual, if David was there then they would sit. “Well, she can’t be so scary after all.” That was the point at which some of them became belligerent. Those were the ones who were more fearful. Because you get over your fear by being aggressive.

How did you plan on defending yourself, not just from the elements, but from the chimps, crocodiles? Was it just naïveté that you weren’t afraid initially?

Jane Goodall: Louis Leakey always told me that if you obeyed certain rules that animals wouldn’t hurt you, and I had total trust. Admittedly, when the chimpanzees were threatening me it was scary. But fortunately, I was never scared until afterwards. So at the time I was quite calm, and I would think, “Well okay, they are being angry at me so I’ve got to convince them that I’m harmless.” So I would be very busy digging holes in the ground, not looking at them, or I would pick leaves and pretend to eat them, and that seemed to do the trick. And then they’d give up and move away.

During your first visit to the Gombe Stream you observed some startling chimpanzee behavior. Could you tell us about your first sighting of the chimps using tools and eating meat?

Jane Goodall: I think it was really sad that my mother had just left when I made the breakthrough observation, because although I was in my dream world, and although it was bliss being at Gombe, I knew if I didn’t see something really exciting before that first money ran out, that would be the end. That would’ve let Louis down. It would be the end of the study.

So on this one day, which I can never forget, walking back through the long grass. It had been raining. It was wet. It was cold and I suddenly saw this dark shape hunched over the golden soil of a termite mound and a black hand reaching out and pushing a straw piece of grass down into the termite mound and withdrawing it. That first time I couldn’t see properly. The chimp had his back to me. When he walked away I saw it was David Greybeard, which is probably why he hadn’t run away. And I went over to the heap and there were grasses lying around and termites kind of on the surface. So I picked grass and pushed it down a hole like he had, pulled it out, and lo and behold, termites gripping on it. I thought, “That’s tool using.” But, it was so surprising ’cause somebody had said to me, “If you see tool using, the whole study is worthwhile.” And the next day it was the rainy season beginning, you see, so the termites were flying. This is when they eat them, mostly. So the next day I actually saw David Greybeard again. I had a much better view. He was with Goliath. And I could see not only the whole of the use of the straw as a tool, but breaking off a leafy twig, stripping off the leaves, which is the beginning of tool making. And that was the thing. We were defined as “Man the Toolmaker.” That made us more different than anything else from the rest of the animal kingdom. We were “Man the Toolmaker” when I was growing up. And so it was after Louis Leakey got my telegram that he sent one back saying, “We shall now have to redefine tool, redefine man, or accept chimpanzees as humans.”

Did you know at the time what a big moment this was?

Jane Goodall: Quite honestly, when I first saw that tool using and tool making, it was exciting. I wished mum was there to share it with, but it wasn’t surprising to me. It didn’t surprise me that chimpanzees could behave this way. They were so obviously intelligent. They were so obviously so like us. So, the full scientific impact of it didn’t really dawn on me until I got back and heard the response of other scientists, some of whom said, “Well, why should we believe what this young untrained girl says,” and pooh-poohed it, basically. But then the National Geographic Society gave money because of that observation and sent out Hugo van Lawick, the photographer. And it was his pictures and film that convinced everybody, well, yeah, she actually has seen this. Chimps actually do use and make tools. And then some of them said, “Well, she taught them.” I’m thinking, gosh, that would’ve been clever to teach them to do something. They don’t learn from us in the wild. In captivity, yes. In the wild, they learn from each other. They ignore us.

Did you observe chimps eating meat in this phase or was it after?

Jane Goodall: Strangely enough, (it was) about two weeks after I saw tool using that I saw David Greybeard up in a tree, and I could not think what he had in his hand. It was pink. And there was a female and a young one or two young ones, I can’t remember, and she was begging. And there were bush pigs down below. And then the young one would occasionally rush down to pick something off the ground and would be charged by a bush pig. And after a bit, I didn’t have very good binoculars, and I realized this is meat. How extraordinary! And then it wasn’t for another probably two months that I actually saw hunting, hunting of a monkey. That was something that Louis Leakey felt, that early humans had used and made tools obviously, but wasn’t quite sure when. And this was the first time that people realized, well obviously, before they used stone tools, which are quite complex, of course they used little bits of twig and grass, but they don’t fossilize, so nobody’d found them. And Louis Leakey had always imagined them hunting and sharing food, and now here were chimpanzees hunting and sharing food.

Chimps may not learn from humans in the wild, but unfortunately chimps contract human diseases in the wild. In 1966 there was a polio outbreak among the chimpanzees at Gombe. How did you deal with that?

That polio outbreak in 1966 was one of the most traumatic times. I think it was even more traumatic because at that time I was pregnant with my son, and we didn’t realize at first that it was polio. It was just this one chimpanzee, Mr. McGregor, coming in, dragging both paralyzed legs, and finally falling out of the tree and dislocating one arm. So he’s then totally unable to move, and we had to shoot him to put him out of his misery. Gradually, other chimps appeared that we hadn’t seen for a while, and they’d be dragging an arm or dragging a leg, or they never came back. It was an absolutely terrible time. The doctor in Kigoma — the European doctor — knew there was an outbreak among people. He should have been administering the polio prevention drops.

Immunization?

Jane Goodall: He hadn’t done it. He should have. He didn’t report it, so we didn’t know there was polio among the human population, so we didn’t know it was polio to start with. As soon as we realized, we immediately got the whole dose of the vaccine from Nairobi, and we would put the required number of drops into a banana. We were feeding all of them bananas at that time. It was a nightmare, because you had to give three doses. And if you gave a dose to a chimp who’d had one dose just the day before, he could get polio, because it’s a live vaccine. So there’d have to be a week’s space between doses. It was a nightmare making sure that a high-ranking one who’d just had a dose didn’t seize a banana from a low-ranking one. So it was a horrible, horrible time, and we lost many wonderful chimpanzees.

It was quite devastating to the study. Even though the casualties might not seem great in the big picture, they were big losses for Gombe Stream.

Jane Goodall: Gombe Stream never had many chimps, and it was a devastating impact on the population. We traced it to two human polio victims. In the South we saw chimps dragging limbs. So we presumed it came from fishermen and villages in the South, and then from chimp to chimp, until it reached us.

What did you observe about chimpanzee behavior that taught you about human behavior?

Jane Goodall: One of the real shocks for me in this whole long-term study was finding out that — whereas I thought chimps were very much like us, but nicer — that in certain situations they can be just as brutal, just as violent as we can. And they have this very aggressive territoriality, so that the males will patrol the boundaries of their territory in groups of three or more quite regularly. And if they see a “stranger” — stranger in quotes, that’s an individual from a neighboring social group — usually if it’s one by him or herself, they chase. If they catch the unfortunate victim, subject them to really, really serious brutal gang attacks, leave them to die of their injuries. And there was one four-year period where the males of one community systematically attacked and left to die the members of a smaller neighboring community. Annihilated the whole group, except for young females that they encouraged to come into their community. It was what I called a four-year war. And then they took over the now vacated territory to the South, very humanlike.

Have you ever been on the receiving end of the chimpanzee’s aggression?

Jane Goodall: I’ve been dragged, hit, buffeted. It’s a chimpanzee trying to prove he’s stronger, which we know anyway, but they like to prove it. One — Fifi’s second son, Frodo — is a bully. He bullies other chimps, he bullies people, and especially bullied me. And it’s actually very scary because he’s the biggest, toughest, strongest chimp we’ve ever known. And it’s like being charged by a tank. There’s nothing you can do except pray, really. Hang on to a tree and hope.

When you first came to the Gombe Stream, what were you hoping to find?

Jane Goodall: When I first got to Gombe we knew nothing really about chimpanzees in the wild, nothing at all. Not much about them in captivity, but nothing in the wild. And so everything I found was new. Everything was important, everything I wrote down in long journals. I would write it up every night, take out my little field notebooks. And it was after I’d been collecting information in this way for about 18 months that I got this letter from Louis Leakey saying that he wouldn’t always be around. He wouldn’t always be able to get money for me. I would have to stand on my own two feet, and that meant I had to get a degree. And there wasn’t time to mess with the B.A. I would have to go straight for a Ph.D. And he’d got me permission to do a Ph.D. in ethology at Cambridge University in England. Ethology? What did that mean? I hadn’t a clue. I’d never been to college. There were no e-mails in those days. So I eventually found out it meant studying animal behavior.

I got to Cambridge, and I was quite excited but a bit nervous. I mean, you know, going in straight with never having been to college before to do a Ph.D. And to my horror, I was told I’d done everything wrong. I shouldn’t have given the chimpanzees names. They should’ve had numbers. I couldn’t talk about personality, mind and thought, and certainly not emotions, because they were confined only to the human. No animal. So why didn’t I capitulate? Why didn’t I go back and call David Greybeard “number one,” and Flo “number six” and Fifi “number 12” and so on? Because I thought back to my childhood, and there were two things which made a big difference to how I reacted to the professors at Cambridge. First, my mother. She always taught us that if you meet somebody who disagrees with you, the first thing to do is listen, then you think. And you really try and see whether what they’ve said is more true than what you have believed. And if you still feel that you’re right or partly right, then you must have the courage of your conviction. That’s one. Secondly, I thought of the teacher I had as a child who taught me absolutely that animals have personalities, minds and feelings, and that was my dog Rusty.

I had a wonderful supervisor, Robert Hind. And although at first he was my sternest critic, he came out to Gombe. He actually met the chimpanzees. He realized very quickly that this way of thinking about nonhuman animals, of the time, was very reductionist, and didn’t explain complex behavior at all. And he really taught me how to write in such a way that I couldn’t be torn apart by all these erudite scientists, this poor little naïve Jane who had no degree at all. And he taught me something, which I tell all the students that I come in contact with, because it’s so clever. I’d written that Fifi, Flo’s daughter, loved her new baby brother, and she was very jealous ’cause when the others would come she would bristle up, chase them away, making angry noises. And he said, “Jane, you can’t say she was jealous, ’cause you can’t prove it.” So I said, “Well no, I can’t. But I’m sure she was, so what shall I say?” He said, “I suggest you say: Fifi behaved in such a way that had she been a human child, we would say she was jealous.” That is very, very clever. It’s got me through my whole life.

People who read your books feel connected to Flo and Fifi, as though they’d met them.

Jane Goodall: They wouldn’t feel connected to “number 12” and “number six.” No way.

Flo was particularly remarkable. Can you tell us about the maternal behavior that Flo displayed?

One of my things I loved learning about the most is chimp maternal behavior, because we find, just as in human society, there’s good mothers and bad mothers. And the good mothers are affectionate. They’re tolerant. They’re protective but not overprotective. But most important, they’re supportive. So they’re prepared to risk being bashed themselves to go and support their child if that child gets into social difficulties. And those young ones tend to grow up to be assertive, to play an important role in the reproductive history of their community. The mothers have more offspring. The males tend to reach high rank. Whereas, the young ones of the less good mothers tend to find it difficult to make close, relaxed relationships when they’re adult. And they’re always a bit tense and nervous, although this decreases with age. And the females do not have as many babies, and the males tend not to be very high-ranking.

What did you learn from chimpanzee mothers that you incorporated into your own mothering?

Jane Goodall: When I had my precious baby, I thought that I was actually learning from Flo. I realized the importance of having a secure base, always being there for the child. Not punishing, but distracting until the child’s old enough to understand. But mainly, you know, being there, having this physical contact, playing with. I always determined, having watched chimpanzee mothers loving their children and having such fun, that I would have the same. And I was lucky, because I could have my son with me all the time. Although in most mornings I was doing whatever work I had to do, was doing a research station, but the afternoons were his. And in fact, I didn’t leave him the first three years for any night. Not once. And so, afterwards, thinking back over it, I realized, well, actually, my mother had brought me up in much the same way. So I don’t know whether I learned from Flo or learned from my mother subconsciously, because children with good mothers tend to be good mothers and those with bad mothers tend to be bad mothers.

They’re not conscious of learning when they’re babies, but somehow it seems to come through. And of course today, human child psychology and psychiatry is pointing more and more to the importance of early experience in our own children, in the first couple of years of life. So I believe this is something which governments should put at the top of their agendas, and they don’t. Again and again, we find early childhood programs being cut, and this is the future. This is our future. If bad experiences in early childhood are at least partly responsible for some of the dysfunctional behavior of adolescence today, then it becomes very, very important to pay more attention to this.

So a woman has to go to work, so she’s got to leave the child. The husband’s working or there isn’t a husband. Some families can’t afford good daycare centers, and there is some question as to whether any daycare center can be really good. So we need to get together as a society to find a way of compensating the child for the fact that the mother isn’t always there. And we find it doesn’t need to be the biological mother. It’s got to be, I think, between one, three, four people that that child can build up a trusting relationship with. That’s the key thing. Somebody or some people, a little group, who can provide absolute security for the child. So a child knows that he can rely on them.

Is there anything you observed in chimpanzee communities that helped you to understand the motivation behind violence in humans?

Chimpanzees basically show aggressive behavior in much the same situations that we do. And yet, I think it’s only humans who can be capable of evil. To me, evil is premeditated. It’s deliberate. It’s thought-out ways of inflicting harm, whether it’s physical or mental. You know, we’re capable on the one hand of much worse aggression. But on the other hand, it works the same way. We can say, “Well, chimpanzees can be altruistic and so can we, but we can think it through.” So while a chimp may leap in to rescue a drowning infant, and a human being may do the same, a human being can act deliberately, knowing that whatever it is they’re doing will harm them in the future, but they do it anyway, whatever the consequences.

So we’re capable of worse behavior and more noble behavior. And basically it comes down to aggression for dominance. We like power for the sake of power. We want to dominate over our fellows. That’s a very human and chimp characteristic, particularly for the male. If we are female, we want the best for our child. We will fight to get the best for our child, whether we’re mistaken or not, but that’s what we think we’re doing. We fight over resources, whether it’s fruit or oil, but being humans we take it all a step further and we get into economic wars. Chimp warfare is like gang warfare, very much the same. I’ve talked to gang members, and they say, “Yeah, it’s much the same. We fight over territory.” We fight over resources, whatever it happens to be. But the sort of cold calculated wars in which we use weapons of mass destruction, they’re far beyond the capabilities of a chimpanzee. It doesn’t have the intellect. But I’d hate to say, if they did, they would be the same as us.

In 1975, what did the chimp named Passion do that was unlike any other chimp behavior you’d seen?

Jane Goodall: In 1975 came the shock of Passion, and her daughter Pom, killing and eating newborn babies of females in her own community. And over about four years, ten infants disappeared newborn, of which six we knew were victims of Passion and Pom. And I thought this was totally aberrant behavior. Then both Passion and Pom had their own babies and it stopped. But more recently, we’ve seen exactly the same with Fifi and her daughter Fannie. So it’s clearly some strange behavior. We do not understand it. But both Passion and Fifi (were) very high-ranking, otherwise, they couldn’t do it.

Who do you think harbors grudges more, male chimpanzees or females?

Jane Goodall: I think male and female probably harbor grudges equally, but sometimes it’s easier for a male to vent his rage immediately. He’s likely to be high-ranking. Females sometimes, if they’re in the presence of males, there’s nothing much they can do about it. But if it’s a young female, and her brother comes who’s higher-ranking than a male who’s perhaps attacked that female, she will remember for quite a long time, and then incite her brother or whoever it is to help her attack the male who hurt her.

Returning to Passion for one more minute. Why do you think she stopped killing infant chimpanzees?

Jane Goodall: Passion stopped killing infants because both she and her daughter got a small baby at the same time, so there was no way that they could act as a team. They were encumbered now by tiny babies.

Do you make a correlation between them killing infants and then having infants, other than the fact that there was just no time?

Adult males will kill an infant of a neighboring group, and even, on some occasions, have partially eaten that baby. But that’s to do with intercommunity aggression, and the mother is the one that they’re actually trying to kill. But within the community, these attacks seem to be like hunting, just like hunting a young monkey, so we have absolutely no idea why they do it. And the following day, the hunter, Passion or Fifi, may sit down peacefully with the mother whose baby they tried to kill the day before, or whose baby they have killed the day before. It’s very strange. And you know, there is so much we still have to find out about chimpanzees. So much.

Was there anything in the upbringing of these chimps that would make sense of this behavior?

Jane Goodall: No. It doesn’t make sense. It’s nothing to do with how you were raised. I really don’t think so. I don’t know what it is. Maybe their newborn smells different and he’s not part of the community, therefore it’s a stranger. But then they eat it just like normal meat. It’s really bizarre.

When chimpanzees hunt, is it opportunistic or is it deliberate?

Jane Goodall: Chimpanzee hunting can be opportunistic, like they come across a baby bush bok lying on the ground and they’ll catch it and kill it. Or it can be very deliberate, like seeing colobus monkeys on the other side of the valley. Hair bristling, reach out, touch each other, and set off on a hunt.

What about adoption or foster parenting among chimpanzees? How does that come about?

Jane Goodall: There is a very, very close bond between siblings, because when a new baby is born the older child is about five but remains emotionally dependent on the mother, travels with her for at least the next three years usually, and maybe much longer. That means that the bond between mother and daughter and son gets stronger, but also the bonds between the brothers and sisters. And it turns out that this bonding between siblings is really important, because if a mother dies and leaves a child who’s older than three, and thus able to survive without milk, then if there’s an older brother or sister, that sibling will adopt the infant and then the infant has a chance of surviving. Because we’ve now had a good many cases where an infant will ride about on the back of the older brother or sister, sleep with them at night. The older one will share food with them. And the males are just as good caretakers as the females. We have occasionally had a non-related individual adopt and provide foster parenting for a motherless orphan, including a 12-year-old adolescent male who was not related — certainly not closely — to a three-and-a-quarter-year-old infant, and save that infant’s life. No question.

If a one-year-old chimpanzee’s mother dies, that chimp will need milk in order to survive. Is adoption by nursing chimpanzees possible?

Jane Goodall: There is one case from a study. I think it was in Ivory Coast, where a nursing mother did look after the baby of her friend, maybe a sister. We don’t know. But we haven’t seen that at Gombe. It’s certainly possible. And the closest we’ve come to it is a very peculiar series of events, where for three years running, a mother stole and looked after the baby of her daughter. Three years running, newborn baby within the first day of life. Gaia’s mother Gremlin stole Gaia’s babies, including twins. She couldn’t keep any of them alive. The second was stillborn, then came the twins. One lived for five days. One lived ten. But fortunately, just two weeks ago, I heard that Gaia has had another baby and this time she’s kept it and she’s together with her mother and all is well. So I’m really, really happy. Why Gremlin behaved that way? Again, it’s one of the mysteries we simply don’t know. Go and get surprises after 50 years!

When a three- or four-year-old chimpanzee’s mother dies, what is necessary? What elements are essential for a successful adoption among chimpanzees?

Jane Goodall: The orphan, in order to survive, needs to be cared for by another individual who’s able to carry that child, to provide reassurance if necessary, to share food. But I think the most important thing is to try and guide the child away from socially roused adult males. Because when big males are in the middle of a charging display, when they’re in this dominance conflict, when they’re socially roused, if an infant gets in the way they’ll just pick it up and throw it. They lose all their inhibitions. So the adoptive foster parent will make sure that the infant keeps out of the way.

How do chimpanzees respond to the death of another chimp in their clan?

Jane Goodall: We’ve occasionally seen chimps responding to coming across the body of a dead adult. They seem very curious. They sniff the ground. They may climb up a tree, sniffing, pick up leaves and smell them. It’s as though they wonder, “How did this individual die?” or “Was there a leopard?” Because the leopard is the one predator that could kill them, although we’ve never seen this at Gombe. But they’re curious. They become very quiet. They don’t do any burial, nothing like that. They just quietly go away. The mother will carry the dead body of her baby for several days until it gets too smelly.

Flint’s response to Flo’s death was perhaps more extreme?

Jane Goodall: Flo’s son Flint was only four-and-a-half, which is very, very young, when his sibling was born. And we now know that all of Flo, Fifi, all of that family, they had very short inter-birth intervals, much shorter than usual, which is five to six years. And so Flint was very dependent when his little sister was born, and he still wanted to suckle. He insisted on riding on his mother’s back while she was carrying the new baby beneath. He insisted on pushing into the nest. And because Flo was old, teeth worn to the gums, she didn’t have the energy to push him away to independence. So when that new baby died, Flo herself was sick. It was some kind of flu. She then took Flint back as her infant after the baby died. And so Flint remained incredibly dependent. And when Flo died he was already eight years old, but it seemed that when Flo died his world came to an end. And he showed signs of clinical depression, immune system weak. He died within a couple of months of losing his mother.

Let’s go back to your own childhood. Where did you grow up?

Jane Goodall: I grew up in England. I was born in London. Then, when I was about five years old, my father wanted me to speak French. So he took a house in La Tuque, and I went there with my mother and my sister, who was about one year old. We were supposed to grow up learning French, but unfortunately the war began, World War II. So we all went to live with my mother’s mother in Bournemouth, which is on the sea in the south of England. That was where I spent the rest of my childhood, and that’s where my home still is today. The house now belongs to me and my sister. She lives there and I visit when I can.

Who were your parents?

Jane Goodall: My mother in particular, played a really important role in my life. I think that most things I’ve done that I’m proud of, even a little bit, I can lay to the wise way that she raised me when I was a child. My father I didn’t really know. He went off fighting in the war. My parents divorced before the end of the war, so I didn’t really know him. I think from him I inherited a very strong constitution, which has been perfect to enable me to live the kind of life that I’ve lived.

But it was my mother… you know, when I was a child I always loved animals, little worms and anything. When I was one-and-a-half years old, she came into my room one day and found I’d taken a whole handful of wriggly earth worms to bed with me. And instead of getting mad and saying, “Ugh! Throw these dirty things into the garden,” she said, “Jane, they’ll die.” So we gathered them up and took them back ourselves.

When I was about four-and-a-half I was staying in the country, which is very exciting because we lived in London at that time. And I met cows and pigs and horses for the first time, and I had a job of helping to collect the hens’ eggs. Well that was fine. The hens were free and they were supposed to lay their eggs in these little wooden hen houses. And I was popping the eggs into my basket, but there’s the egg, so where on the hen did the egg come out? I couldn’t see a hole like that. And apparently, I was asking everybody and nobody told me, so I decided I must find out for myself. I remember so well. Okay, four-and-a-half, but I remember seeing a hen. She climbed up this little sloping plank into this house where she would spend the night, but they also had the nest boxes. And I followed. A mistake! Squawks of fear, she flew out. So this was not a safe place for a hen. I went to an empty hen house, hid in the straw at the back and waited, and waited, and waited, and the family had no idea where I was. They were all searching. The dusk was falling. My mother sees this excited little girl rushing towards the house all covered in straw. Instead of getting mad at me, you know, “How dare you go off without telling anyone?” — which would’ve killed the excitement — she saw my shining eyes and sat down to hear this wonderful story of how a hen lays an egg. So honestly, if you look at that story with hindsight, that has the makings of a little scientist. The curiosity, asking questions. You can’t find out by asking questions, you decide to find out for yourself. You do it wrong. You make a mistake but you don’t give up. You try again and you learn patience. It’s all there.

Who was Jubilee?

Jane Goodall: When I was about one-and-a-half years old my father bought me a stuffed toy chimpanzee. And Jubilee was made to celebrate the jubilee of the King and Queen, and he’s about life-sized, I mean about this size. He had a music box inside him. He was very realistic. I still have him today. He was my favorite toy. I think it’s coincidence that he was a chimpanzee, because I had already loved all animals. But it is just kind of strange that it’s a chimpanzee that I came to study and know so well.

Could you tell us about prosopagnosia? It’s difficult even to say.

Jane Goodall: I can’t say it myself. All through my life I’d been very embarrassed, because I find it very difficult to recognize people’s faces until I know them really well. So I can be with somebody for a day and meet them the next day. Unless they have a sort of unusual face, I may not know who they are and it’s really embarrassing. And it wasn’t until about 15 years ago that I met somebody else and we started talking about it. And I said, “You mean you can’t either?” And he said, “Yeah.” So I then wrote to Oliver Sacks, the famous neurologist and told him about this, and he said I have this. He told me its name. The common name is “face blindness,” and it’s a neurological condition. They’ve done some very in-depth investigations of some people with this. They tend to be rather brilliant people. The people they interviewed were two doctors. And some people have it so badly that they literally, after ten years, don’t recognize someone. And it can spill through into not knowing that your sense of direction is pretty bad. And there’s nothing you can do about it. So I usually make up for it by pretending to recognize everybody. And then, if they say, “But, we haven’t met before,” I say, “Well you look just like somebody I know.” You have to do something, but there’s nothing you can do about it. And since I wrote that in a book, in Reason for Hope, about this condition, so many people have said, “Thank you for saying (it). Now I know what’s wrong with me. I always felt so embarrassed.” So it’s helped a lot of people. My sister also has it. My mother, absolutely not. She knew everybody.

Did your prosopagnosia — “face blindness” — make it more difficult to recognize individual chimps at first?

Jane Goodall: Yes, it did. It did take me longer to know the chimps too. But I haven’t got the most extreme form. Once I know somebody, I know them. But chimps are no easier than people. And the person who helped me realize that this was a condition is none other than our amazing videographer. I said, “Bill, do you mean it took you a while to recognize the chimps?” He said “Yeah.” He’s the one. And then I found more and more people with the same strange difficulty. Now I understand. It’s still embarrassing. So I find I’m looking for something. If I know I’m going to find somebody again, I’m looking for, you know, “Does she have a mole, or a hair growing on the end of her nose?” Does he have this, that or the other, you know? There are certain kinds of faces that are easy to remember. But then there’s others that really are not. I could meet you tomorrow and not immediately know you and you would be upset. You can’t help it. So I just know everybody.

Do you have a memory of your very first library?

Jane Goodall: I have a memory of a house that was always filled with books. We never called it a library, per se. It was after the war broke out, when I went to live with my grandmother and it was a whole household full of women, and every single room had a bookcase. My bedroom had a bookcase. The books I loved, which my mother always helped me to get, were Dr. Doolittle, and then I discovered Tarzan. I still have these books, books about explorers in Africa, books about animals. Always animals, animals, animals. But at first we couldn’t afford books. We had very little money. We couldn’t even afford a bicycle, let alone a motor car. So I would go to the library and I would take books out. And then if I loved them, I’d go and take them out again. And then I began to haunt second-hand book shops where you could buy books really cheaply, and that’s basically how I put together my books that I still have — poetry books, bits about philosophy. You can sort of see my changing interest as I grew older. But it was my mother who, you know, books were always so important. Once a week on Sunday we were allowed to read at the table. That was a treat. The only book that normally we could bring to the table was if the discussion led to an argument about something. We could go and fetch a dictionary or an encyclopedia, but otherwise it was a treat for Sunday. And I’ve just always loved books.

Was there one book in particular that influenced your direction in life?

Jane Goodall: There was no one particular book. It was an accumulation. I do remember the first Dr. Doolittle book. He rescues circus animals and takes them back on his boat to Africa. And they have all these adventures and that made a deep impression, taking these animals back to Africa. And then, of course, the Tarzan books. Well, this is nothing to do with — there was no television when I was young, so it was the books, and they were second-hand books. And I, of course, fell in love with Tarzan. I mean I was 11 years old, and you know little girls at 11 can passionately fall in love with fictional heroes. And then he goes and marries that other stupid Jane. I was really jealous. I know I’d have been a better mate for Tarzan myself, which I would’ve been. So that was really the time when I thought, “I will grow up, go to Africa, live with animals and write books about them.”

And everybody laughed. How would I do that? We didn’t have money. Africa was still thought of as the dark continent. It was filled with poisoned arrows and savages and cannibals and things like that, dangerous wild animals. We didn’t have any money, as I’ve said. And there were no 747s going back and forth, no tourist industry, nothing like that, just these stories of explorers that I’d read, and Dr. Doolittle and Tarzan. But I think the reason that people really just thought I was crazy was because I was the wrong sex. Girls did not do that sort of thing back then. But again, it was my mother. “If you really want something, if you work hard, if you take advantage of opportunity, if you never, never give up, you will find a way.” That was her message. There was never a moment in my house, either with my mother, either of her sisters or my grandmother, where somebody said to me, “Well, you can’t do that. You’re a girl.” Outside the family, yes. Inside the family, no.

It’s telling that you showed early signs of leadership in the Alligator Club. What was your role in that club?

Jane Goodall: Holidays in my childhood, two girls came to stay, one my age, one the age of Tootie, my sister. Their parents had been friends before the war. They’d gone off to the South of France and things like that, when there still was some money. So they came, and I was always telling them about nature. We went on nature walks, and I decided that we would have a magazine, and that we would have a club, and I called it the Alligator Club. Why? I have no idea why it was the Alligator Club but it just was.

Courtesy of It’s quite funny. I’ve got one of those magazines that I did still. I was nine years old, ten maybe, and I’d been reading this book which was my childhood bible, The Miracle of Life. It wasn’t written for children at all. It just went through evolution and everything like this. And I was drawing really complicated pictures of like the mouth parts of a mosquito. And these children who were all younger than me were — I’d draw it and label it in one issue, and they had to send the magazine back with answers. I would send out the next issue and they had to answer. It’s so funny. There’s no way an eight-year-old or a seven-year-old could possibly know this, but that was what I was asking them to do.

What kind of a student were you? Did you like school?

Jane Goodall: I absolutely hated school. I hated the sport, although I wasn’t bad at it. I liked the lessons that they’re learning. I liked the learning, but I didn’t like school. It was a girls school. I didn’t like being shut in. I didn’t miss boys. It didn’t have anything to do with boys. I just wanted to be out in nature. I did not want to be coped up in a school, so I lived for the weekends when I could go to riding school. I lived for the evenings when I could take my dog Rusty out walking on the cliffs. So no, I did not like school, but I was a very good student. I never came less than third in the end-of-term exams.

Did religion play a role in your childhood?

Jane Goodall: My grandmother was married to a clergyman. He was like a Congregational minister. I never met him. It’s one of my real sadnesses. He died before I was born, of cancer. So my grandmother obviously had been to church with him. She used to go to church, not every Sunday. We didn’t really talk about religion that much, but the idea of God was just part of our life and I never thought much about it.

I had a tree in the garden I called Beech. I made a will which I made my grandmother sign, leaving me this tree in perpetuity. It was a beech tree and I used to climb up this tree. And when I was up there, I felt very close to the birds and the sky and the clouds. I used to take my homework up there. I used to go up with a book if I was sad. And somehow, the wind and the birds and the tree and the leaves and God were all intermingled as I was growing up. It was all kind of one, and I didn’t really question it.

Then when I was 15 I fell passionately and platonically in love with a “God’s man.” He was a Welshman. He had this beautiful Welsh voice. So then I would go to church every Sunday, twice in a Sunday, three times if I could, in the middle of the week if I could. And I would sit in the back gallery. He was a funny little man, really. Trevor Davies. And then I could not get enough of church. That’s when religion really meant something to me. It was quite an important part of my life, I think, because of him, but beyond him.

You’ve mentioned the war a couple of times. What was the impact of World War II on your childhood?

Jane Goodall: World War II was such an important part of my childhood. It changed everything. My father went off. He joined the army. My mother’s friends were being killed. We had to put blackout up in the windows every night. We weren’t in a war zone, that was London. We were down on the coast, but very often the bombers would drop their bombs if they hadn’t bombed anywhere before they flew across the Channel, because then if they were shot, it was safer for them. You know, because then they didn’t explode so easily. So we had bombs drop near us. But I think what really, really, really made an impact was at the end of the war, when the pictures of the Holocaust came into the newspapers. These living skeletons, these rows of dead bodies. It was utterly shocking, and that was the first time. I remember climbing up Beech and trying to work out in my mind about this good, wise God that had just been a part of my childhood without my really thinking about it, and this utter evil, this complete cruelty, and how to reconcile these two elements.

Dr. Goodall, all through your adolescence, you were called Valerie Jane. That changed when you graduated from high school. Was that a sort of re-identification of yourself?

Jane Goodall: I was called Valerie Jane all through my young childhood. Then I became known as V.J. because it was quicker, so I was V.J. In my riding school I was V.J., and at school I was V.J. I think I was about 13 or 14, something like that, when my mother discovered something she hadn’t known before. Valerie was the name of my father’s first girlfriend. It was dropped like that. I became Jane. So I was either V.J. or Jane from that moment on.

Did you study field biology in high school? Was there a supportive community for your ambitions?

Jane Goodall: When I was at school I did biology. I wanted to do zoology, but it was a very small school. There was nobody qualified to teach zoology, so the three of us who…I mean, we were told that I was the only one wanting to study zoology. It turned out there were two other girls as well. But there was nobody qualified to teach us zoology, so we did biology. Field biology hadn’t come, there was no such thing as field biology when I was in high school, so I did biology. I didn’t much like it. It meant dissecting fishes and things like that. I still wanted to go to Africa. If I couldn’t go to Africa then it would be Canada, or it would be South America, somewhere in wilderness areas. And that was the dream, but for girls, there was no career in that sort of thing. And when the career lady came to the school, and she heard that I wanted to go out and study animals in the wild, she just laughed and said, “That’s impossible. The best thing…” It was my mother talking to her, or no, it was my headmistress, I think, ’cause I was sick, and the headmistress questioned her. And she said, “No, no. Tell this child that we can arrange a nice career for her photographing pet dogs and cats.”

So you finished high school. What did you do for work in the years following graduation?

Jane Goodall: When I left school, I was 18. I’d done really well in all my exams. My friends all went — most of them went — to the university, but we didn’t have enough money. And in those days you had to be good in a foreign language in order to get a scholarship. It was just after the war, and I wasn’t good in a foreign language. I still am not. So it was, again, my mother. She said, “Well, do a secretarial course, and then maybe you can get a job in Africa.” Well, that’s what I did. And the first job I had was in Oxford, working at the registry. So I actually got the whole idea of what it was like to be a student without any of the work. All my friends were students. And then I got a job in London with documentary films. Not secretarial at all. And that was amazing, so I learned all about the whole of making a film. And it’s been so useful to me in my life. And then I got this letter from a school friend inviting me to Kenya. That was the opportunity. And so I quit the job in London, couldn’t save money there. Went home, worked as a waitress. That was one way of getting some money.

This was an old-fashioned family hotel, around the corner from us, by the seaside. People didn’t have much money, so after the war they came down from up north and they stayed for a week. So I had to work really hard for a week. All the other staff were professionals — professional wait people. And at first they resented me totally. And it was kind of bizarre because my uncle at the same time was presenting me at court to the Queen. So here I was. And anyway, the other waiters and waitresses thought that I would be snooty and just, you know, leave them in the lurch and go off if I felt like it, and go out to dinner with boyfriends, but I didn’t, you see. I took it seriously. I was going to do it. I was going to do it well. So they accepted me, and I learned all about these fascinating… they were all Irish Catholic. They’d come over and they were professionals. And I’d befriended — or I was befriended by — the wine waiter, who married the head waitress. And, you know, it was a whole new life, but it took about four or five months before I’d saved up enough wages and tips. And that was by telling all the people at my tables that I was saving up to go to Africa, so they gave me a little bit more, perhaps. And finally I had enough money. Got a return fare by boat, which was the cheapest. And so I was 23 years old. I said goodbye to family, friends and country, and set off on this amazing journey which, you know, has led me along the path that my life followed ever since.

After you had begun your work in Africa, while you were studying at Cambridge, you began to create a permanent research center at Gombe Stream. What went into that effort? What were some of the obstacles that you encountered?

Jane Goodall: I’ll never forget the day when I suddenly realized I had to go back to continue at Cambridge to do another term. And I suddenly thought, “We don’t have to close the camp. We can find somebody. You will come and at least temporarily carry on.”

We found a young man that wanted to study micro fungi, and he came and took over and made a few observations. My cook made a few observations. It wasn’t scientific, but at least there was somebody there recording, you know, Goliath and David Greybeard and things like that. And then this worked so well that we asked the Geographic if they would find a student. And so the first student came out. I think it was 1964. And that was the beginning of a series of students, and building up a research center which eventually had connections with Cambridge University in the UK and Stanford in U.S.A. And it became a large multidisciplinary field station, very exciting, many students. And it was probably at its peak when suddenly one night it all came to an end with rebels from Congo coming over the lake, kidnapping four students, and taking them away to where we knew not. We didn’t know where they’d gone. We didn’t know who’d kidnapped them. It was absolutely devastating, and it could very well have brought the entire thing to a close.

But you went on and created the Jane Goodall Institute. How did that come about?

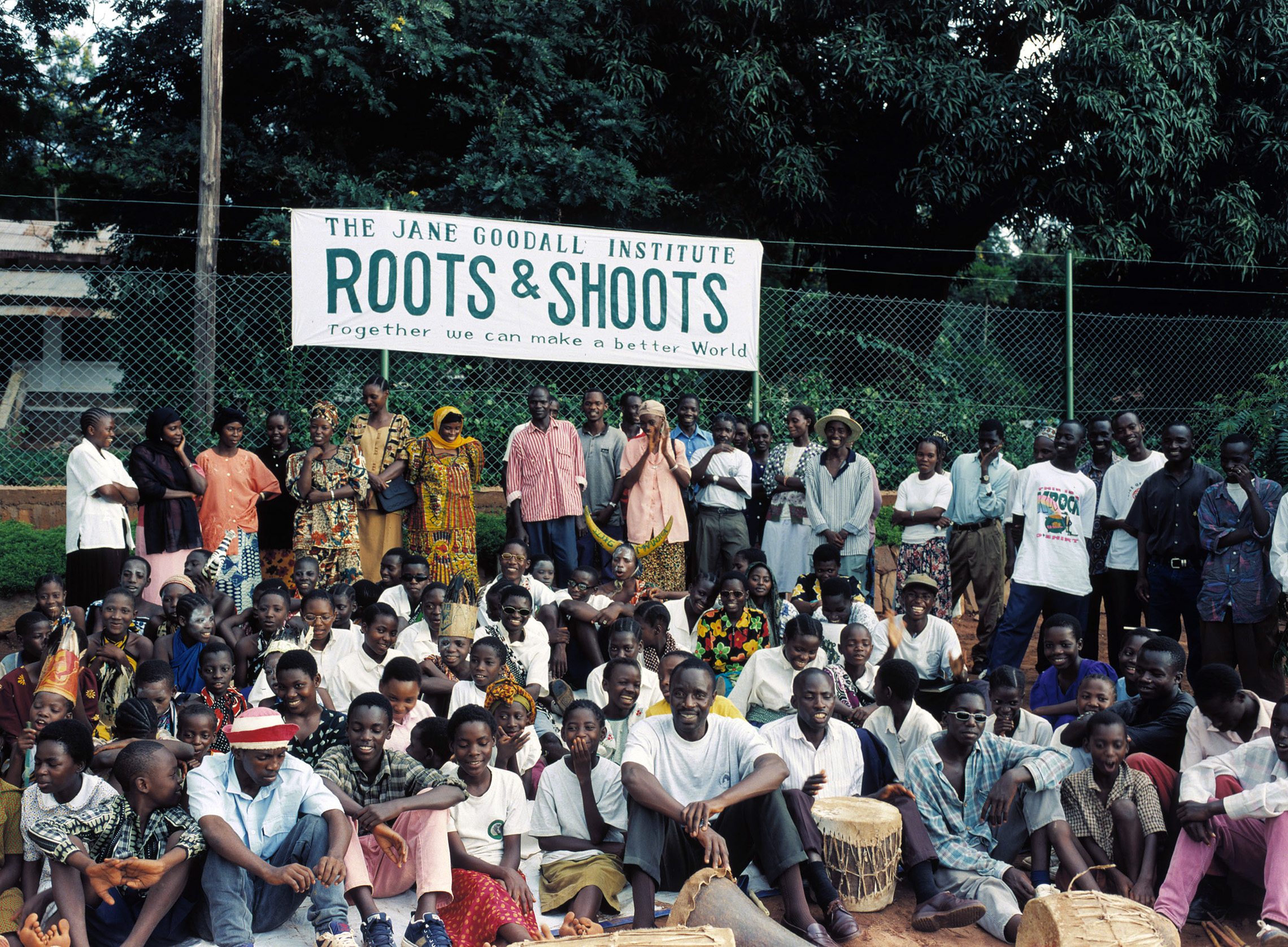

Jane Goodall: The Jane Goodall Institute was created by this wonderful woman, Princess Genevieve di San Faustino. And it was because, in 1975, when my students were kidnapped, I could not get the grants that I’d been getting before, because there was no Ph.D. in residence. It wasn’t allowed by the Tanzanian government after that kidnapping. And so it was Jenny who said, “Well, if we create a Jane Goodall Institute you can raise money yourself, and it can be a not-for-profit.” So basically it was created to raise the money to keep the research at Gombe going, but with the idea that it would also be intended in the future to raise money for conservation and for conservation education. So that’s why it was created. It was because it was the only way of getting the money that was necessary to keep going.

It took a few years, didn’t it, for that to happen? What was the role of the Getty Endowment?

Jane Goodall: The Getty Endowment. After creating the JGI, for a long time it just sat on paper, and I was still getting some money from Geographic and other such organizations, the Leakey Foundation. And then the National Geographic produced a film, Among the Wild Chimpanzees, and I thought, “Well, maybe we can use this.” Do premieres, maybe raise some money, maybe create an endowment so that I’m not always living hand-to-mouth, so that there can be some continuity of the Gombe research. So it won’t be, at the end of every year, “Will I be able to get money for the next year?” Let’s build up some kind of endowment or trust. So using that film, premiering that film, which the Geographic allowed me to do in five cities, I asked Gordon Getty if he would match the money that I could raise. And actually, he put a ceiling on it, which doesn’t sound much these days: a quarter of a million dollars. And I raised far more than that, but he wouldn’t match it up beyond the quarter million dollars.

After more than 25 years with the chimpanzees at Gombe, you attended a conference in 1986 that was sort of a turning point in your professional career. Could you tell us about that?

Jane Goodall: For several years I worked on writing a book, The Chimpanzee of Gombe: Patterns of Behavior, in which I was going to summarize the research results of the first 15, 20 years, whatever it was. And as I went in deeper and deeper into this, I realized that to write the kind of book that I probably should, I needed to learn all sorts of things which I would’ve learned had I been an undergraduate, which I had never learned, which had always made me feel a little bit at a disadvantage if I was talking to a real scientist. So the Ph.D., yes. But what about all this ground work, all this learning about endocrinology and things like that? So I taught myself these things in order to write the book, the things I felt I needed.

And when the book was published, and I felt for the first time that I was the equal of these white-coated scientists in the labs and so forth, my great friend Paul Heltne — from the Chicago Academy of Sciences at that time — said, “Let’s have a conference to celebrate. This is the first really long-term book on one species.” And so we brought together, for the first time, chimpanzee researchers from all over Africa, and some noninvasive captive research like zoos and things. And during that four days, we had one session on conservation, and one on conditions and some captive situations, and those two sessions changed me totally.

I came out as an activist, because in that session on conservation, seeing right across Africa the destruction of habitat, seeing the beginning of the bushmeat trade, the commercial hunting of wild animals — including chimps — for food, the session on the secretly filmed footage in some of the medical research labs, utterly shocking. And now I have this new self-confidence, because of publishing that book and learning what I didn’t learn, know before. I came out as an activist. And since that day, I haven’t spent more than three weeks in any one place, except once when I tore the ligaments on both ankles and I needed an extra week or so to get better.

Since then I’ve been traveling the world, going in wider and wider circles, trying to raise awareness about the situation we’ve plunged the planet into, starting with the plight of the chimpanzees, learning more about the plight of the forest, realizing more about the problems of Africa. Realizing how many of those could be laid at the door of the developed world and our unsustainable lifestyles, and our greed in taking more of the resources than is our fair share, and the other elite communities around the world, including in Africa. Learning how everything is interrelated, learning more that made me realize, “Well, I have to spend time in the U.S., I have to spend time in Europe. I must spend more time in Asia.” So it’s become a ridiculous lifestyle, traveling 300 days a year.

I wouldn’t do it if it didn’t appear to be having an impact on the people who come to listen to my talks, trying to find time in between to write books, because I love writing books. I love sharing by writing and trying to use the gifts I was given. It’s not something you learn how to do, to be able to communicate. Yes, you can get better at it. But I always wanted to write books to share. And then I found that not only could I write books to share, which people wanted to read, but, but I could also give lectures that people wanted to come to, and it made an impact. And if they didn’t, I wouldn’t do them. I could go back to living in the forest, which is what I love. But how can I go and live in the forest when it’s disappearing? And I feel that maybe there’s something I can do, by inspiring others to take action so that we create, hopefully, a critical mass of people who think differently.

There’s now a chimpanzee sanctuary in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Can you tell us how that got started?

Jane Goodall: Yes, Tchimpounga. When I was learning about the plight of chimps across Africa, I was lured by the then-ambassador Dan Philips and his wife Lucy to Burundi, because the chimpanzee situation there was pretty grim. Chimps were being hunted in the then-Zaire and brought over the border. I met chimpanzees who’d been bought as pets or taken to hotels. We began confiscating them and set up a little temporary halfway house for chimpanzees, ready to move them into a more permanent sanctuary. And then Dan Philips and Lucy moved to Congo.

I went to Congo, and there, met for the first time, in the meat market, a little chimpanzee infant beside the cut up body of his mother. And we were able to go to the Minister of the Environment, who confiscated the chimp. And a woman living locally (Graziella Cotman) said she would look after him. And that led to a whole spate of confiscations. And Graziella’s infant family grew and no longer could she keep them in her home. So at that time, Conoco, the oil company, was working near Pointe Noire on the coast, and they agreed to build a sanctuary. And that sanctuary now has 141 orphaned chimpanzees, most of whose mothers have been eaten. And it’s a nightmare. We have to feed them. We are trying to put them out on some islands. We have to compensate the people living on the islands. We have to deal with the government. There are changes in regime which negate everything that we organize. We’ve worked out with one government and now we have to start all over again with a new government. And meanwhile it’s very, very expensive country. It was tied to the French franc for a long time, and it’s actually a nightmare. And this is just one of many sanctuaries in Africa for chimpanzees, for gorillas, other animals as well. I wish that we didn’t have to be involved with sanctuaries. I wish there was no need to be involved in sanctuaries. We have to build up endowments for them.

Dr. Goodall, can you tell me what happens when you see one chimp for sale in a cage or one chimp is taken out of the wild? What is the truth behind seeing that one chimp?

Jane Goodall: It’s sad to say that for every baby chimp that one rescues, probably ten individuals have died. We don’t actually see most of the babies. They die on the scene of slaughter of the mother. Others are taken off into villages and raised by children as pets, but they will die too, or be eaten. And when a hunter shoots the mother, there may be other individuals in that community to come and attack the hunter, and they will be killed as well. So for every infant chimpanzee that survives to be bought, to be rescued, at least ten will have died. And it means that — whereas, when I began in 1960, there were around, well between one and two million chimpanzees in Africa — today there’s no more than 300,000 max, and they’re spread over 21 nations, many of them in small isolated pockets of forest with just about no chance of long-term survival.

And those 21 different countries are not talking to each other about a conservation effort?

Jane Goodall: There is no unified agreement between the different countries with the chimpanzees. There are organizations that are persuading each of those countries. That’s GRASP, the Great Apes Survival Plan of UNEP (United Nations Environmental Programme). GRASP is going around to all the different governments, getting them to sign a great ape management plan. But creating laws and implementing those laws are two different things. While in some respects, I think we’re moving closer to solutions, in other respects we’re losing ground.

This bushmeat trade is the commercial hunting of wild animals for food. It’s not to feed hungry people, it’s to make money. And when the logging companies — the foreign logging companies — have moved in and made roads, the hunters from the towns follow and they shoot everything. In the old days, subsistence hunters didn’t do that. They didn’t shoot a mother with her baby. What’s the point? That means in the long run you will be harming your own future. But today, yes, shoot a mother with a baby and shoot an elephant, a gorilla, a chimpanzee, an antelope, a bird, a bat, anything that can be cut up and smoked or sundried, and trucked in on the logging truck to the markets to be shipped out, sometimes overseas. And it’s totally unsustainable. And not only is it unsustainable for the animal populations, but the people living in the forest who were subsistence hunters, who’d lived in harmony with the forest for hundreds and hundreds of years, now they face a damaged future as well.

Can you tell us about the TACARE reforestation education project?

Jane Goodall: TACARE (Take Care) was started to sustain villages that border existing wildlife programs. It supports their coexistence by creating alternate forms of revenue via education, water sanitation, family planning and HIV-AIDS education.

Can you tell us how that program started and what it’s doing now?

Jane Goodall: One of the film teams that’s always coming to film the Gombe chimps wanted to fly over the whole area in the small plane, and I went with them. And although I knew there was deforestation outside the park, I had not realized that it was total until that day, and looking down, seeing more people living on the land than it possibly could support. Seeing how this had led to soil erosion, led to bare, almost desert-like situations, where there had been forest when I arrived. Realizing that the Gombe National Park was a tiny 30-square-mile island of forest, surrounded by completely bare farmland. Realizing people were struggling to survive. Questioned how can we even try to save these precious chimpanzees — of which, by then, early ’90s, there were not many more than a hundred — when all the surrounding people are having such a difficult time. So that led to our Take Care program. And that, from the very beginning, was holistic, designed to improve the villagers’ lives in many different ways. Everything from tree nurseries to reforestation to regeneration of existing forest, farming methods best suited for the degraded land, ways of restoring fertility to the soil without pesticides.

Gradually getting money from other organizations, so that we could include water supplies, better sanitation, school rooms for the over-populated schools, dispensaries, encouraging the government to supply and staff the dispensaries that we built. Working with groups of women, providing microcredit opportunities so they could start their own environmentally sustainable development programs. Providing scholarships for girls to keep them in school, realizing that all around the world, as women’s education improves, family size drops. Working specifically with women, and providing information about family planning, very important. If you’re going to grow more food, you’re going to have more babies. If you have more babies, the situation will continue deteriorating. So family planning and HIV-AIDS education. And at the beginning, working with George Strunden, this wonderful man who designed the project, everyone said, “You’ve got to focus. You can’t do everything.”

George and I felt strongly that everything was interconnected. There was no point dealing with health unless you dealt with the environment. There was no point dealing with water programs unless you’re also dealing with food, and so on. And it’s been one of the most successful programs of it’s kind in Africa. We’re replicating it. And I think one reason for its success is, never did white people go into a village and say, “Well, you’ve got yourselves in a mess. This is what we’re going to do to help you.” It was a Tanzanian team from the very start. We still have that same team today, all these years later, who went into the village and sat down in the traditional African way to listen to the problems and to ask the people what they thought would make their lives better. And what was it? Was it conservation? No. It was education for their children and health. So that’s where we began, working with local Tanzanian authorities.

The Jane Goodall Institute employs this wonderful young man, Lilian Pintea, who has state-of-the-art technology when it comes to creating maps. Satellite imagery, GIS, GPS, teaching the local people to use this complex technology, working with Digital Globe that supplies the imagery for Google Earth, creating these maps, so that people for the first time, they can see, “Here is my house. Here is his house. This is where our village boundary is.” Helping them to make the maps required by the Tanzanian government for village land use, which sets in stone: this percentage will be for agriculture, this percentage will be for whatever. Including a minimum of ten percent of land for conservation. So because they love TACARE so much, they’ve sat down with Lilian and worked their conservation areas into a kind of corridor, so that all this land that was treeless six years ago now has trees that are about 20-foot high. And I’ve stood and looked at it. And this is just allowing the seemingly dead stumps to regenerate, that’s what it’s taken. The land is resilient. And now, the chimpanzees will have an opportunity to once again move out and interact with other remnant groups, which may be able to move into this new area and be safe.

Where do you find the balance between limiting medical testing on chimpanzees and the importance of disease research to humankind?

Jane Goodall: It turns out that the vast percentage of animal experimentation has not benefited human health or animal health. And there is a whole body of research growing into ways of conducting medical experimentation, pharmaceutical testing, without using any live animals. When it comes to chimpanzees — because they’re so like us, because their DNA differs from ours by only just over one percent, because you could have a blood transfusion from a chimp if you match the blood groups, because the immune system is so like ours that they can catch or be infected with all known human diseases, because the brain is so like ours that it’s just almost the same but a bit smaller — they have been used as guinea pigs, to learn about diseases which otherwise are unique to us. Very little of that research has actually led to results that have benefited us.

Thousands have been used for HIV research, because you can put the human HIV 1 and HIV 2 into a chimp’s blood, and the virus will stay alive, but the chimps don’t get the symptoms of full-blown human AIDS. It has been established that HIV 1 and 2 came from two different chimp populations where a retrovirus mutated. It started off as the chimpanzee version of simian AIDS. But the research in the labs hasn’t led to anything very useful in HIV/AIDS research.

It’s basically been stopped. And it was one of the two who discovered the HIV retrovirus — Bob Gallo and Luc Montagnier — it was Bob Gallo who actually said at one of his big AIDS conferences in Arusha, Tanzania, “I am boxed in by inappropriate results from research on chimpanzees.” He said that. He had done it himself, but that’s what he said. And so, fortunately, because of the animal rights movement, there has been a flurry of research into alternatives. Computer simulation, cell culture, tissue culture, even organ culture. All kinds of things which are new ways of looking at disease and cures.

So there needs to be a new mindset, that the moment the animal researchers, the animal experimenters will say — and they do say — “We do admit that animals feel pain…” most of them say that now, and therefore, we use as few as possible and treat them as well as possible. We use them as far down the evolutionary scale as we can, but we’ll always have to use some. I want us to say something different. I would rather we said, “We now admit that this research into animals, because what we know about what animals are, who they are, is inappropriate. It’s cruel for the animal. It’s very often torture from their perspective. So let’s get together around the world, with these extraordinary brains that we have, and find ways of doing without them altogether as soon as we can.” Now it’s very different to work towards a goal to eliminate animals than it is to say, “Well, we’ll always need some, but we’ll try and use less.” That’s two different goals. And the goal that I want will say, “Okay. If that’s the goal, then let’s have some Nobel Prizes for these alternatives to animals.” Let’s have scientific approval instead of establishment pushing away, because they want to do things the way they’ve always been done, because it’s a multibillion dollar industry.

One of the issues that the Jane Goodall Institute has brought to the world’s attention is the conditions under which animals are kept in captivity.

Jane Goodall: The first time I went into a medical research lab, I was so shocked. I was so upset. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. Little chimpanzees rocking from side to side in cages that were like microwave ovens, with a little slit of a window, and otherwise, just steel with air going through a vent. And when the doors opened, there was this chimpanzee with dead eyes rocking from side to side like this. And there were many of them in this condition. And there were monkeys in tiny cages going from side to side, from side to side, up and around. It was totally shocking. And although I knew about it, I wasn’t prepared for what I saw. And that changed me completely and totally, and I realized that — never mind the ethics of using them or not to study human diseases or cures — the conditions in which they’re kept, these conditions were totally, totally, totally inappropriate and absolutely inexcusable.

The first thing that I did after that visit was to sit down with all the — it was the National Institutes of Health people. The top ones came for this visit, and I always sat at a table, and there was coffee on the table. And my mind was just reeling. I think I was probably trying not to cry. And there was dead silence. And I looked up, and I saw they were all waiting for me to say something. It was one of those terrible moments when, you know, what could I say with this emotion that was surging around inside me? And I said, “Well, I think every caring and compassionate human being will feel the same as I do about seeing animals in these conditions.” It was actually brilliant, because if they disagreed with me they were basically saying they weren’t caring, compassionate human beings. But at any rate, that led to the very first of the meetings between the medical research people, the veterinarians and the welfare people. And I got a lot of flack from animal rights people who believed I shouldn’t be sitting around the table talking, that this was compromising my values to talk to them. How can you change people’s attitudes if you don’t talk to them? And in fact that lab, which was at that time called SEMA, was under the new directorship of a man who decided eventually that everything in the lab was wrong. Changed it completely. I talked to him last week. He said, “Jane, please come back. I really, really, really want you to see what we’ve done now.” He said, “You said last time you came it was better.” He said, “Now, I think you will really approve and appreciate of what we’ve done.” He said, “Yeah, we still have the chimps there, but it’s completely different.” So you know, that was the first.

Those were all young chimps. Then I went to the LEMSIP, the lab in New York State, up in New York State, and that was the first time I saw chimpanzees, adult chimpanzees, in these five-foot by five-foot cages. And I was led in by the veterinaries. This lab, by the way, is closed now. There’s none of the chimps left. And I was led into this torture chamber by the veterinarian, and he introduced me to Jo-Jo. He said Jo-Jo is very gentle. And he left me there, and I had to put on this white mask. I had gloves and a cap, and booties and a white coat. And I knelt down and looked at Jo-Jo. And if he’d been angry and mad, it might have been easier to bear, but he wasn’t. He just had this slightly puzzled look in his eyes like, you know? And I just couldn’t help thinking of the chimps at Gombe, their nests and the breeze and the stars in the sky. And what’s he got? He’s got bad concrete, no, he had iron bars on the floor, iron bars all around. One tire, motor tire; that was it. That was all that was in that cage. Nothing else. And so tears began to trickle down under my mask and he just reached out, this gentle finger and wiped them away, and sniffed his finger and wiped them away. And then the veterinarian came. He knelt down beside me and put his arm around me. He said, “I have to face this every day.”

And that was where I realized that the people working in the labs, they’re either completely hard and they stay because they don’t care, or they leave if they can’t take it. Most of them leave. Or they stay because they feel that they can do something for the chimps by staying, at least provide some friendship. It was one of those moments that you can never forget, and it just makes you go on struggling and doing what you can. A lot of those labs are now closed. Many more can be closed, but then those chimps all have to have sanctuaries. Money has to be raised, but it can be done. The chimps are not really being used much anymore.

Don’t they have to be taught how to be chimps again once they leave that environment?