A career seemed to me something rather like a prison sentence. That was how I viewed a career. I would start at the bottom and I'd work my way up the ladder and then I'd retire and, after a little bit, I'd die...And, to be an outsider seemed to me to be very, very attractive.

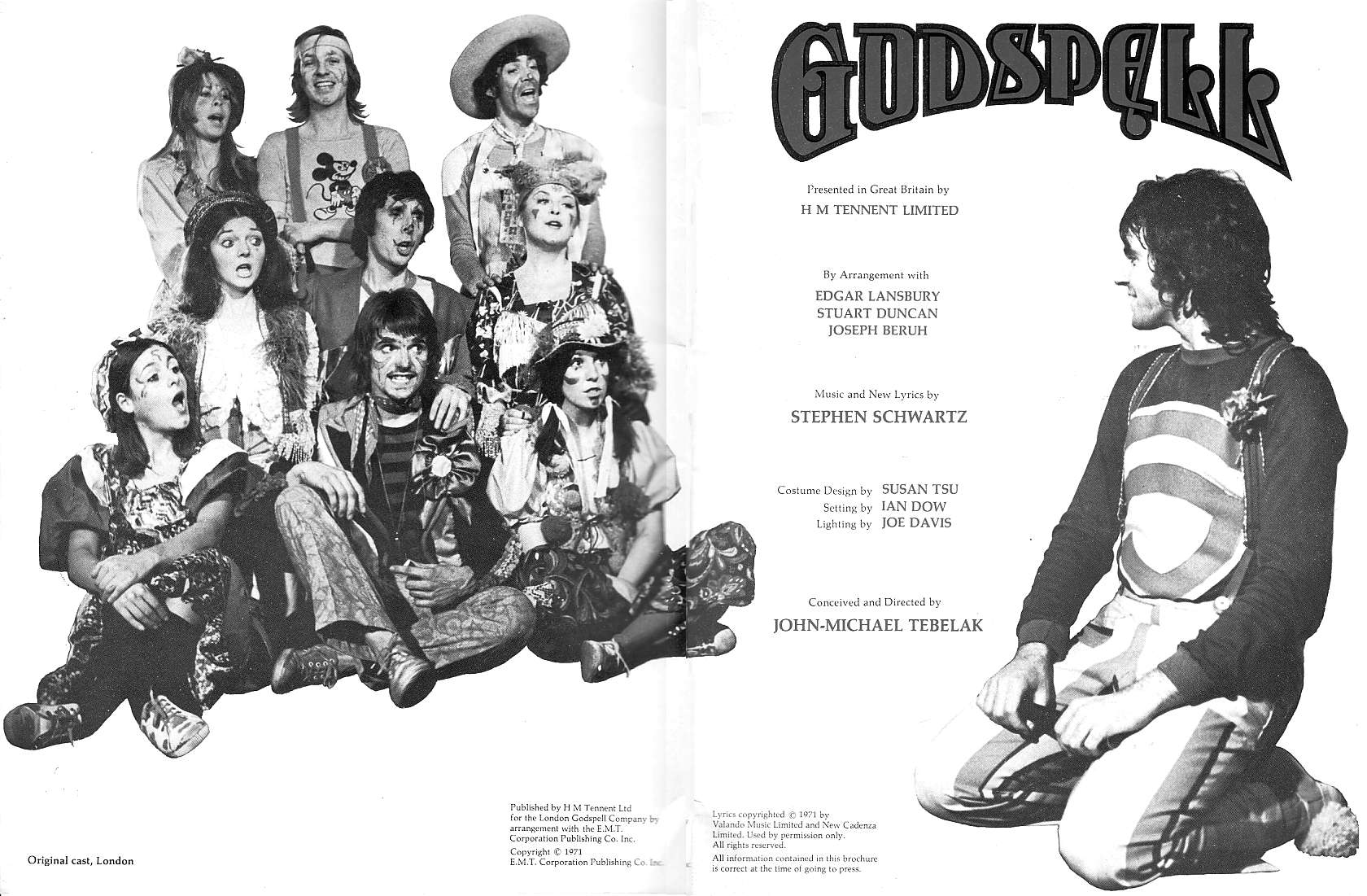

Jeremy Irons was born in Cowes, England, on the Isle of Wight. An indifferent student, his teachers and family were unsure what he would do for a career. After failing to win admission to veterinary school, he determined to pursue a career in the theater, an interest that had been piqued by acting in plays at Sherborne, his boarding school. He worked as an assistant stage manager in a small rep theater, then entered the two-year program of the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School. After graduation, he stayed in Bristol for three seasons, playing the juvenile leads in plays by Shakespeare, Noel Coward and Joe Orton. In 1971, he moved to London to pursue a career in film and on the West End Stage. He won the role of John the Baptist in the London production of the musical Godspell and soon came to the attention of casting directors for film and television. In Simon Gray’s play the The Rear Column he was directed by the famous playwright Harold Pinter, who recommended him to film director Karel Reisz. After viewing some of Irons’s film and commercial work, Reisz cast him opposite Meryl Streep in The French Lieutenant’s Woman, for which Pinter was writing the screenplay.

Before production of The French Lieutenant’s Woman began, Irons was cast in another leading role, Charles Ryder in Grenada Television’s 11-part adaptation of Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited. When a technicians’ strike interrupted shooting of Brideshead, the schedule was extended. Irons had been assured he would be done in time to start work on The French Lieutenant’s Woman, but when the time came, shooting on Brideshead was still not finished, and Grenada offered the actor a difficult choice: give up his first leading role in a feature film, or walk out on the series. Walking out could mean being permanently barred from professional film and television work in England. He believed he was in the right, but knew that a long lawsuit would probably prevent him from doing the film as well.

Irons refused to be intimidated; he walked out, and production on Brideshead was shut down. The television company relented and worked out an arrangement that enabled Irons to finish both jobs. As it happened, Brideshead Revisited was a phenomenal worldwide success. When The French Lieutenant’s Woman hit the theaters in 1981, Irons’s position as an international star was consolidated.

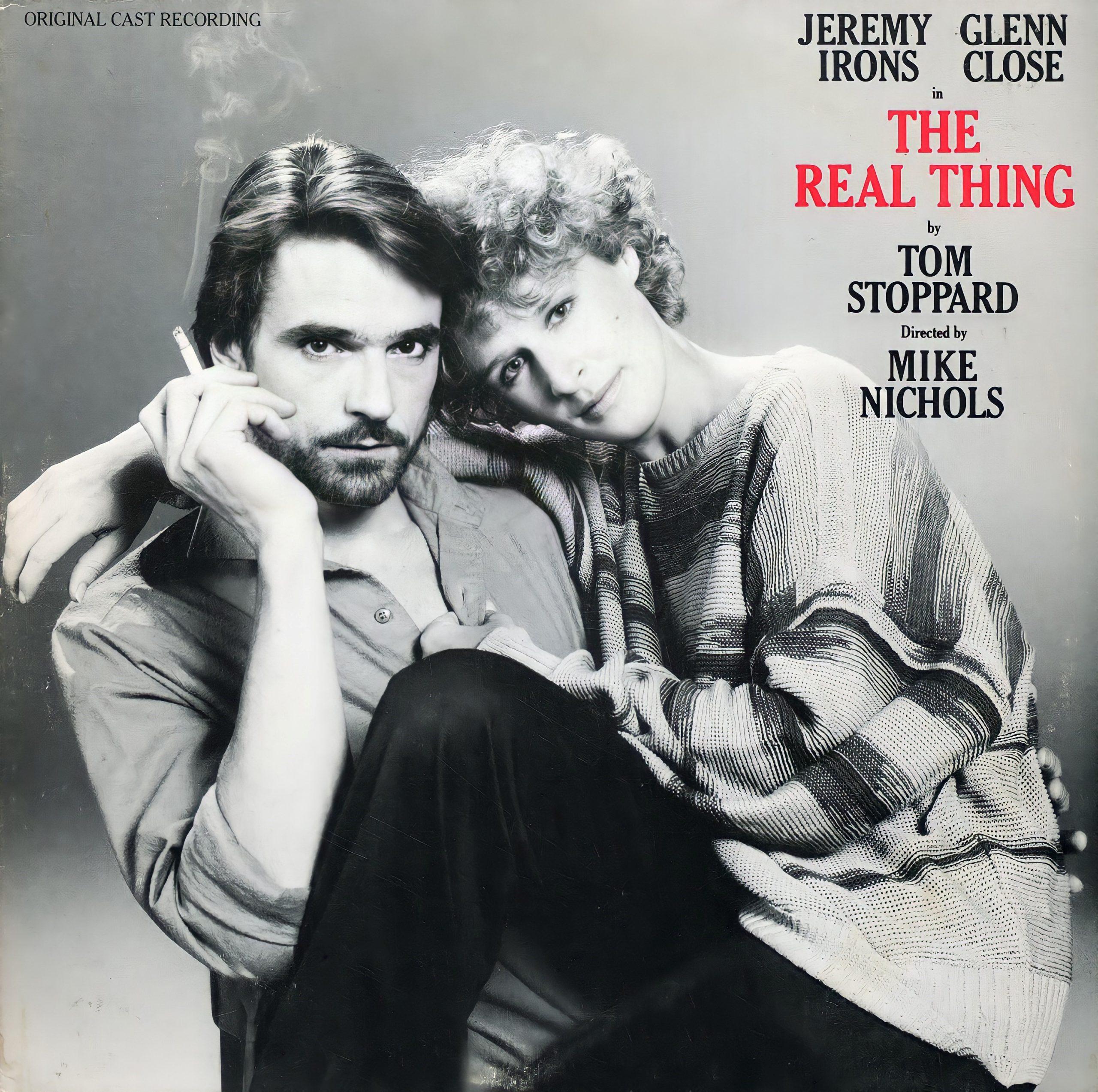

Throughout the 1980s, Irons continued to work onstage, undertaking classical roles with the Royal Shakespeare Company. He made his Broadway debut in 1984, playing opposite Glenn Close in The Real Thing by Tom Stoppard. His performance in that play won him a Tony Award for Best Actor. Irons and Close worked together again in Reversal of Fortune (1990), the film for which Irons won a Best Actor Oscar. His other notable film roles include The Mission, Swann in Love, Die Hard: With a Vengeance, The Man in the Iron Mask, Lolita, and The Man Who Knew Infinity.

Despite his enormous success in film, Irons has remained active in the theater, television and the recording studio. He portrayed Professor Henry Higgins in a 1997 recording of My Fair Lady with the opera star Dame Kiri Te Kanawa. In 2003 he starred in a New York revival of Stephen Sondheim’s A Little Night Music.

He returned to the London stage in 2006, after an absence of nearly 20 years, to star in Embers, adapted by playwright Christopher Hampton from the novel by Sándor Márai. He received a second Emmy Award and a second Golden Globe in 2007 for his performance as Sir Robert Dudley in the television mini-series Elizabeth I.

Irons played the British Prime Minister Sir Harold Macmillan in the play Never So Good by Howard Brenton for Britain’s National Theatre in 2008. The following year, he returned to Broadway to star with actress Joan Allen in the new play Impressionism by Michael Jacobs. From 2011-2013, Jeremy Irons starred as Pope Alexander VI in the Showtime historical series The Borgias.

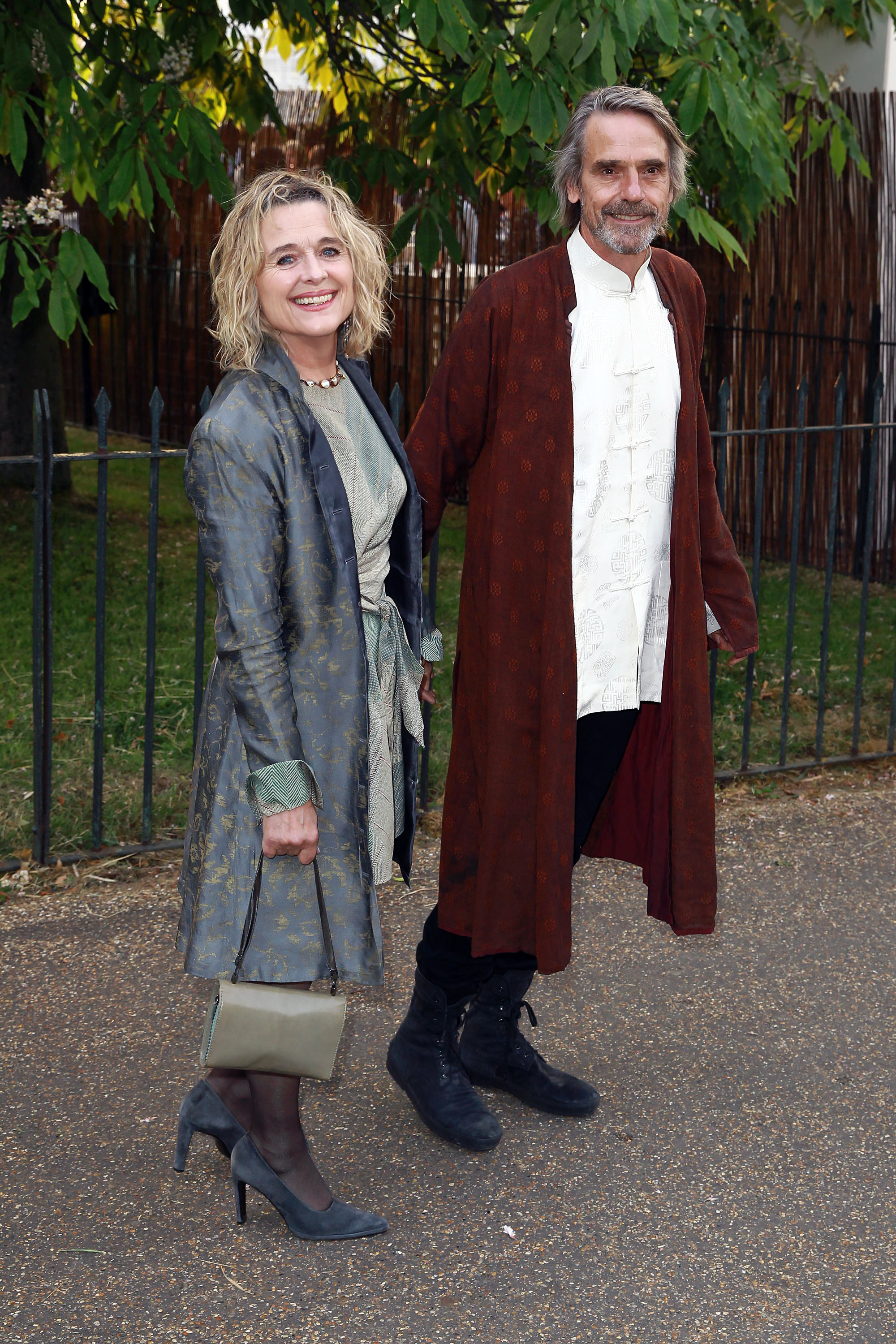

In 2011, he was selected as a Goodwill Ambassador of the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. He is one of the few actors who has received the “Triple Crown of Acting” — winning an Academy Award for film, an Emmy Award for television, and a Tony Award for theater. Jeremy Irons is married to the actress Sinéad Cusack; they have appeared together in two films, Stealing Beauty and Waterland. They have two sons, Maximilian and Samuel, who appeared with his father in Danny, Champion of the World.

“A career seemed to me something rather like a prison sentence. That was how I viewed a career, that I would start at the bottom and I’d work my way up the ladder and then I’d retire, and after a little bit I’d die. And I thought there’s nothing I want to do like that really.”

Just out of school, with no particular prospects, young Jeremy Irons answered a “help wanted” ad placed by a small theater in Canterbury, England. The ad called for an assistant stage manager, but once inside the theater, Irons knew he had found his calling.

He had already made a small name for himself on the London stage when international audiences got their first look at him in the television mini-series Brideshead Revisited. Although Irons made his reputation as a romantic leading man in films such as The French Lieutenant’s Woman, he has never shied from unusual or unsympathetic roles. He amazed audiences with his performance in the French language film Swann in Love, and as psychotic identical twins in Dead Ringers. He played a spine-tingling villain in Die Hard: With a Vengeance, a dying artist in Bernardo Bertolucci’s Stealing Beauty, and the tormented Humbert in the second screen version of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita.

After seeing Irons’s portrayal of Claus von Bülow in Reversal of Fortune, von Bülow’s real-life attorney, Alan Dershowitz, declared that “Jeremy Irons is a better Claus von Bülow than Claus von Bülow.” The Motion Picture Academy agreed and gave Irons an Oscar for Best Actor.

As familiar as Irons’s face may be to adult moviegoers, even more children know his voice as the villainous Scar in The Lion King. Audiences of all ages can be grateful that he has lent his face and voice to an extraordinary variety of roles in some of the most memorable films of the last 30 years.

We understand you hadn’t really settled on a career path when you left school at 17. What were your plans?

Jeremy Irons: I had done a fair bit of traveling during the holidays, in my school days, with my guitar and discovered that I could live on it. Admittedly, I traveled with a sleeping bag, but I could always find somewhere to lay my head. I could always find the money for food. So I had a sort of — a passport — and I traveled in Europe and around England with that. I had a family home that I could always go back to if things went badly wrong. In fact, I had two family homes by then. I was — looking back at it — waiting and listening, which I think is one of the secrets.

I had a walk with my father on Hampstead Heath. He lived in London on Hampstead at that time, and I said, “I think I want to try to be an actor.”

He said, “Oh, God. If you look at people who are actors, they tend to have an awful lot of marriages and they don’t seem to be very happy.”

But he was a great father. By then he’d failed with my brother, who was off sailing around the world trying to find the secret of water, and still is, strangely enough.

So my father was quite keen that I wanted to do anything, and he said, “Well, I don’t recommend it, but I would say to you that if you don’t try it, you’ll never know, and you’ll always resent me for not supporting you. So see if you can get a job.”

I got a job off the back of a newspaper as a — what they call an “acting ASM,” I think it was called then. An acting assistant stage manager in a theater in Canterbury, a rep theater. A small wage but just enough to get by on, and I made props, and I walked on, and I changed scenery, and I realized that I just loved it. Not the acting. I wasn’t acting. I liked the theater. I liked the people. I liked the time that we worked. Now looking back, I see what I was doing, but at the time I didn’t know. You never know at the time. What I was doing was finding a way not to have to be stuck with any of the sort of people I’d been educated with, but finding a way of creating the life of a gypsy really, of being able to move from camp to camp, singing around the fire, getting to know those people and then moving on maybe with some of them — or maybe not — to another place.

A career seemed to me something rather like a prison sentence. That was how I viewed a career, that I would start at the bottom and I’d work my way up the ladder and then I’d retire, and after a little bit I’d die. And I thought there’s nothing I want to do like that really. Nothing I want to do enough but I’d like to — I had read a lot of autobiographies of actors, from Burbage (Shakespeare’s leading man), through to Charlie Chaplin, Noel Coward, and all the people in between. That was while I was at school, under the notion that I was collecting them but with no knowledge as to why. But in fact, a lot was — you know, you don’t collect things without reason, and a lot of their lives soaked into me and their attitudes. And to be an outsider seemed to me to be very, very attractive.

Did you see actors as outsiders?

Jeremy Irons: I think so. They are privileged in that they can, at their best, stand beside the king’s ear and tell him, “You ain’t got no clothes on, chummy,” and get away with it. I think that’s what we should do. I always worry in this country when actors get knighted and lorded and decorated. I think, “No. Stay away. Stay awake. Keep behaving badly. Keep stirring the mud.”

Perhaps you already saw yourself as an outsider and you found a profession that allowed you to be one.

Jeremy Irons: That’s right. I loved working in the theater but I knew nothing. So what was the next step?

My next step must be to go to drama school. Well, I get into drama school, so I did that. Fortunately, my father was able to pay the fees, and he said, “But I’m not paying for you on the holidays. You know, any extra money you want.” So I worked as a builder, building new bathrooms for people outside their houses where they didn’t have bathrooms ,and that enabled me to run a car and to go through my two years of theater training.

Now, in my theater training, I showed no aptitude at all. Funny enough, four nights ago I had dinner with three other colleagues who were at theater school with me, and Tim Piggott-Smith — who was in The Jewel and the Crown, I don’t know whether you saw that — he had always thought I would give up very quickly, like in a year or two years after leaving drama school. He said, “You had no talent.” And I didn’t. I wore clothes well, I decorated the stage well, but I wasn’t an actor in the way that Tim was, or many of the other students.

I remember we would stay for the weekend — a group of about ten of us — and the staff would interview us as a group, asking us questions so we’d hear everybody else’s answers.

I remember particularly when the principal — a great man called Nat Brenner who is sadly now dead, a great man of the theater — he was talking to us, and he was asking people why they wanted to become an actor and what they had been doing. And there were people, they had done — they’d sold ice cream in Mongolia, they’d made ballet shoes in Brisbane, they had done extraordinary things. He said, “What have you done?” I said, “Well, I haven’t done anything really. I sing a bit.” He said, “Why do you want to be an actor?” I said, “I don’t know. I just think it’s quite nice.” Anyway, he talked to me. I think he saw the window that I was and took me on. But as I say, in the two years I learned various skills. I learned a little bit about the theater, about styles, about how to speak, how to stand, how to sing — not using my nose like Bob Dylan, but actually sing — using my diaphragm. And at the end of the two years, five of us were chosen to go down into the theater, into the Bristol Old Vic company itself.

I thought, “Well, they want someone to stand up at the edge of the stage looking nice.” You know? Went down there for three years. I outlived them all. I stayed on and I finished off playing the juvenile leads — very badly. And eventually somebody in a coffee morning said — one of the theater club people said, “I expect you’ll be moving on soon,” and I thought, “Oops, when the audience starts saying that, it’s time to go.” So I moved on. And by then I decided — and I suppose this is one talent I do have, is that I know my direction usually — and I knew that I didn’t want to keep being a repertory actor. Repertory actors move around from town to town, repertory theater to repertory theater, and do maybe six-month contracts, but they don’t earn very much. And I knew that I was too middle class, that I wanted a family, I wanted a house, I wanted a mortgage. And I knew I wouldn’t be able to afford one doing that, so I thought, “I have to go to London. I have to go to London and do a West End show or a film.” So I came to London, and to live — I thought I needed something to live because I don’t want to have to take a job because I need the money — so I worked for a domestics agency which cleaned houses and sometimes did up people’s gardens.

Because I had a car, I was quite reliable, so they used to use me quite a lot. And I auditioned for everything, because I hated auditioning. I found it very difficult and thought I’d better get good at this. So I kept doing auditions, and if I was offered the job, I’d say, “I’m sorry, I can’t do it. I thought I could do it, which is why I came to the audition, but I can’t.”

Eventually I did an audition for an American show called Godspell, by John Michael Tebelak, which was coming to be launched in London. Americans enjoy uniformity in a way that the British don’t; they wanted everybody of a sort of nice chorus line height and here I was, this person who was a good three inches taller than anyone else on the end of the line. Every time I sort of slouched, a little voice would say, “Stand up, Jeremy, could you please?” Anyway, they gave me the job. I did that for two years in the West End. And I remember one night sitting on the stage during a song someone else was singing. I played John the Baptist, and David Essex who played Jesus, was sitting on the other side. And I thought, you know, I slipped these theatrical shoes on without a lot of thought, but they fit me like kid gloves.

At that moment, you knew, “This is it.”

Jeremy Irons: Yeah. I had given myself to the age of 30. I said, “At 30 I think I could change careers. Much after that will be difficult. So let’s see how I’m doing then.”

What would it have taken to satisfy you that this was the right choice in life?

Jeremy Irons: That I was happy, and that I was succeeding, that I was having a relationship, which is what I wanted, and that I was earning money, and having a life that I was proud of.

How old were you during Godspell?

Jeremy Irons: Maybe 25. So I had about five or six years left, but I knew that I was on the way.

We were speaking earlier of taking risks in your career. I suppose at 30 you decided to continue being an actor. Where were you in your career when you made that decision?

Jeremy Irons: When I was 30, I was shooting Brideshead Revisited. None of us knew it would be as successful as it turned out to be. Through complicated reasons there had been a strike of the technicians, and our schedule had been shifted. I had also been asked by a director called Karel Reisz to make a film called The French Lieutenant’s Woman in the March of that year when Brideshead should have been finished.

When we came back together to make Brideshead after the strike, we had been delayed by two or three months, and we could see that the schedule was going to have to be even longer anyway, because of getting to Oxford for the locations and various other things. My producer rang me up and said, “Would you restart on Brideshead?” And I said, “Well certainly. Of course I would, but I’ve told Karel that I’ll do this movie in March.” He said, “Well, that’s fine. We’ll work that out.”

Well, when the time came to work it out, I got a rather heavy message from the television company saying, “I’m sorry. We can’t release you. We need to work through that period.” And a lot of people were involved in that.

And I thought, “Wait a minute. I have a contract.” I actually hadn’t signed the contract but I had a verbal contract with my producer; he understood what I had said. We were filming up north, so I came down to London and went to see a lawyer. He was good as silk, and he said, “You’d win if what you tell me is true, but it would take a year and a half to come to court.” I said, “Well, that’s hopeless, isn’t it? We’ll be finished by then, the film will have gone.” So I went back north to work, leaving an agent in tears in London. And after one day’s work, went back to my hotel room, and thought,

“You’re being very British about this, Jeremy. You’re 30. If you’re going to make it in this life you’re going to make it in your 30s. And you think you’re right, and you’re stepping down because you’ve been told you can’t win in court — If that’s the way you’re going to manage your life then fine, but don’t expect too much.” So I sat down. I had a couple of martinis and dinner and then returned to my home and wrote a long letter to the chairman of the television company telling him that I was off unless by six o’clock the following day he would agree to release me to make this film. And I laid out — I knew everything he would do to me. I said, “I know you can bar me from the union. I know you can sue me.” They by then had spent eight million, I think. I said, “My house is worth 85,000. That’s about all I have but you can sue me for that. I’m not a hysterical actor. I’m just an actor against the wall.” You know. I called my lawyer the first thing in the morning and read it over the phone to him and said, “That’s what I want to send.” He said, “If you’re absolutely sure. You seem to know the downside.” I said, “Yes.” He says, “All right. Fax it to me and I’ll have it delivered around,” which he did.

By six o’clock that day there had been no response. I checked with my producer whether there had been any response, and he said no, there hadn’t. I got in my car and drove down to London to a film premiere. The following day I was fairly shaky. I was walking off a set. In this country it’s a big thing — I think in America, too. A lot of people were depending on me. It was a big cast, a big crew and all this. I was in every scene for two weeks, and I was gone.

I went to lunch with my agent in a restaurant. There was a phone call during lunch from the chairman of the television company, who said, “Will you come for tea?” I said, “Yes.” I asked my agent for a valium, went to walk the dog on Hampstead Heath, and then went down to have tea with the chairman of Grenada, who was very cross, said he felt let down. I said, “I feel let down. We’re both in the same boat.” He said, “If I can work something out, will you go back to work?” I said, “Certainly. I’ll be back there tomorrow morning.” He left the room for about 15 minutes, came back in and said, “I’ll work this out in three weeks. Give me three weeks.” So I went back to work. Three weeks later they tied the two things together, the film and the television, so that the film paid for the downtime in the television, and the television invested in the film, and I was able to do both. But on the journey down, the night before when I had driven down in my Volkswagen Beetle, a long drive on the M6, about a four-hour drive, I remember thinking “That’s it. That is it. Now if I’m not going to act, what am I going to do? I could be an agent. Should I write? Well, can I write? I don’t know.” But I knew that was it. And I knew that I had taken my destiny in my hand in a way that I had never felt before and I think that’s when I grew up. I knew I was my own man. I could do anything.