'Jimmy, when you have a blow to your pride and a horrible defeat, you can give up, or you can look on it as a way that God opens you to do different and even better things.' And, I said 'Ruth, I've been defeated for Governor in Georgia, and my political career is over. I don't have any future.'

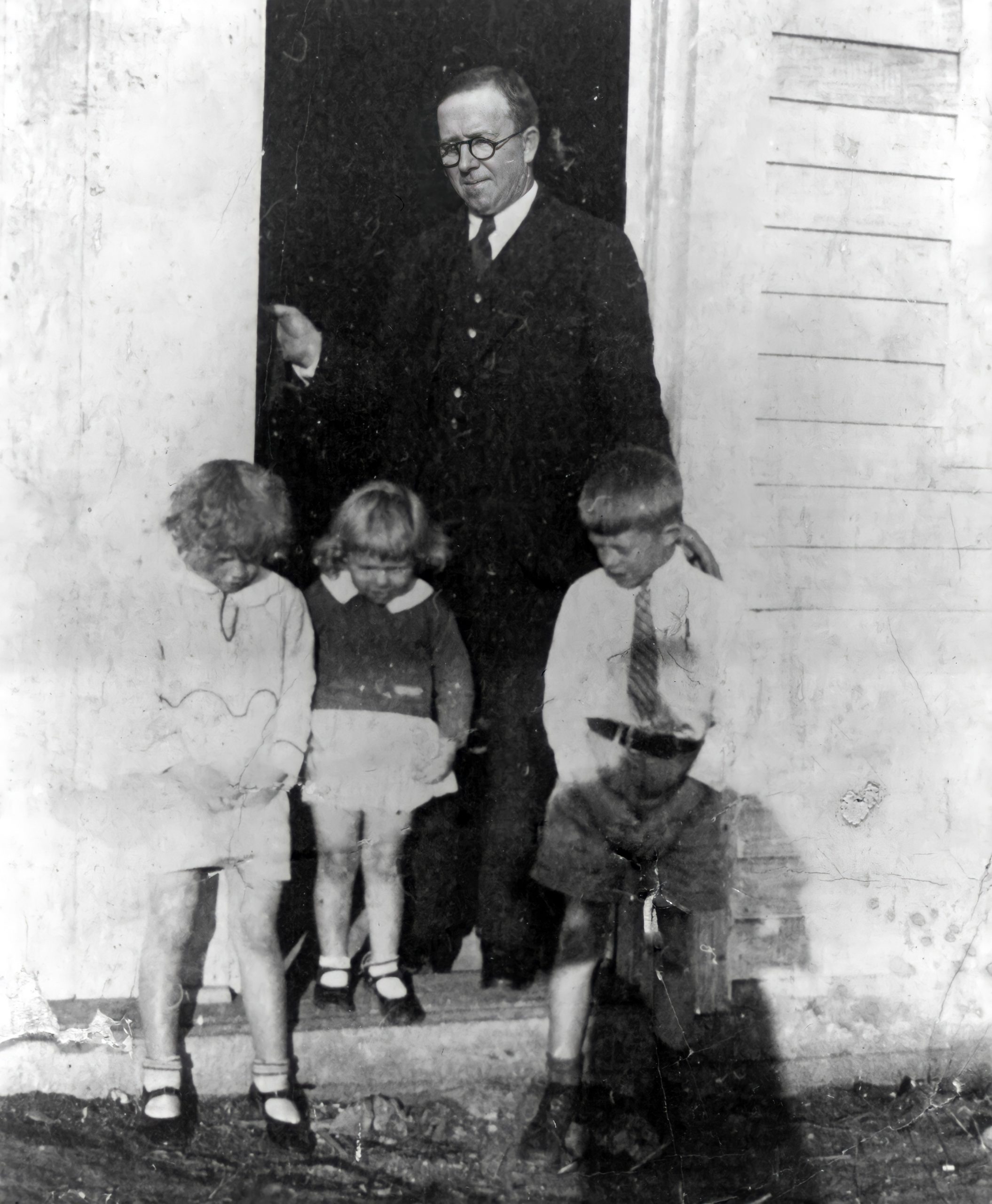

James Earl Carter, Jr. was born in the small farming town of Plains, Georgia. His father, James Earl Carter, Sr., known as Earl, was a farmer and businessman. His mother, Lillian, was a registered nurse. When Jimmy Carter was four years old, the family moved to a farm in the nearby community of Archery. Jimmy Carter has described the world of his childhood movingly in his 2001 book, An Hour Before Daylight: Memoirs of a Rural Boyhood. Although the Carter family home lacked both electricity and running water, the Carters were one of the more prosperous families in the community. Most of their neighbors — and young Jimmy’s playmates in Archery — were African American, but the rigid code of segregation required the separation of the races in school, in church and other public places. Carter’s mother, Lillian, flouted the custom by volunteering her services as midwife and health practitioner to her neighbors. His father carried on the more traditional role of the Southern landowner, eventually increasing his holdings to 4,000 acres, worked by mostly black tenant farmers. Earl Carter expanded his business dealings as peanut broker, warehouseman and retailer of farm supplies and equipment.

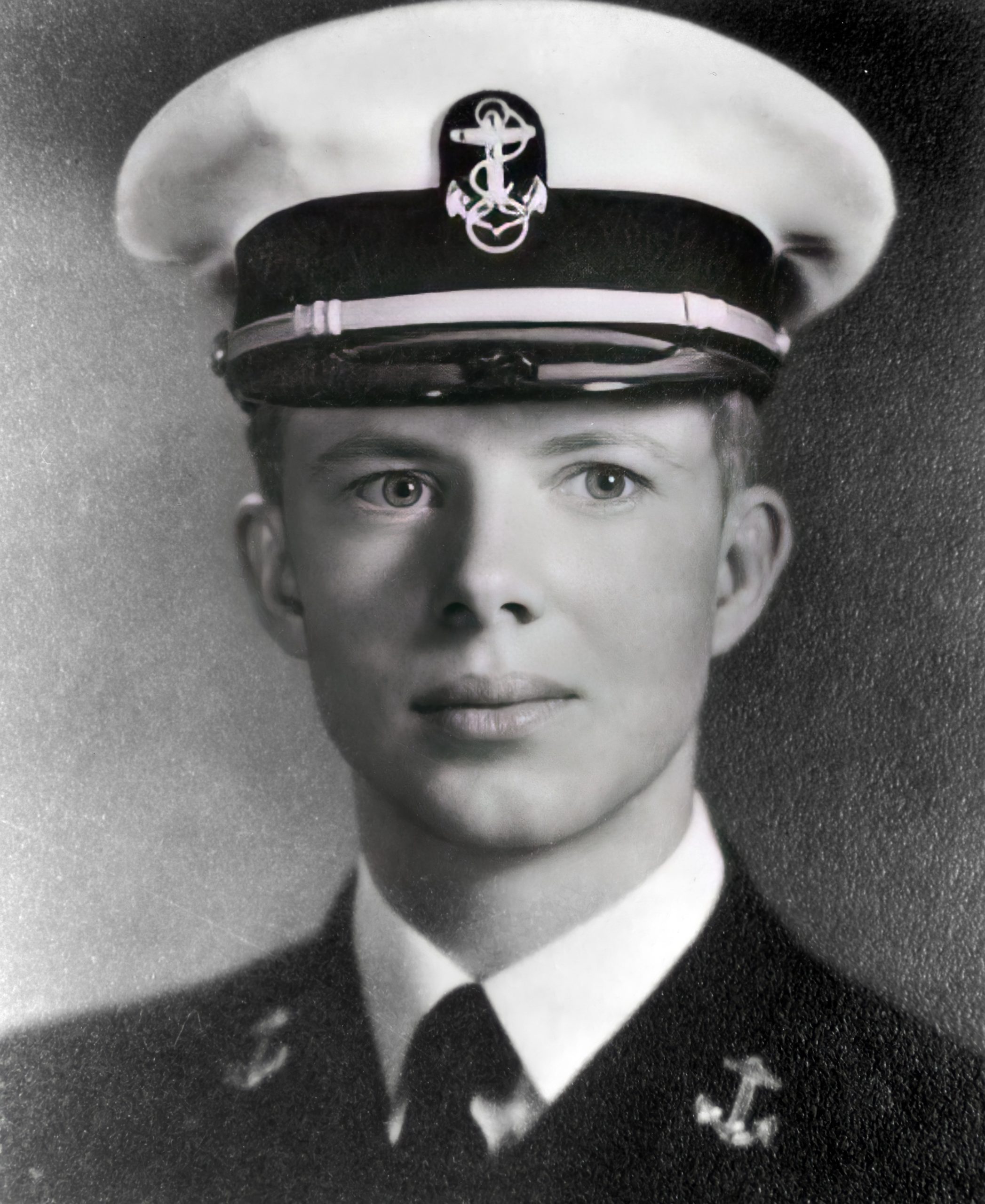

Jimmy Carter was educated in the Plains public schools, and studied at Georgia Southwestern College and the Georgia Institute of Technology before entering the United States Naval Academy. He graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree and was commissioned as an Ensign in the United States Navy in 1946. Shortly after graduation, he married Rosalynn Smith of Plains.

After serving on conventional submarines in both the Atlantic and Pacific, Carter joined the Navy’s pioneering nuclear submarine program. After graduate studies in nuclear physics at Union College in Schenectady, New York, Carter was selected by Admiral Hyman Rickover to serve as engineering officer of the Sea Wolf, America’s second nuclear submarine.

Carter had reached the rank of full Lieutenant when his military career was cut short by the death of his father. In 1953, Carter resigned his commission, and returned with his wife and three sons to Plains to run the family’s farm and continue his father’s warehouse and farm supply businesses. Rosalynn, who initially resisted the move back to Plains, became the firm’s bookkeeper, and over the next years, Carter’s Warehouse grew into a profitable general-purpose seed and farm supply operation.

At the time of his death at age 59, Earl Carter was serving in the Georgia House of Representatives, and Jimmy Carter too felt an obligation to serve his community. He was elected chairman of the Sumter County school board and then first president of the Georgia Planning Association. At the time, Georgia, like the rest of the South, was wracked with controversy over school desegregation. Carter entered the Democratic primary for the Georgia State Senate in 1962 as a moderate, seeking to counter the influence of the state’s strong segregationist faction. His opponents made a crude attempt to steal the election, registering fictitious voters in alphabetical order and recording the votes of persons long deceased. Carter exposed the fraud in court and took his seat in the Georgia Senate. Once in office, Carter proved himself one of the most able and dedicated members of the body and was easily re-elected to a second term. He has provided a fascinating account of these events in his 1992 book, Turning Point: A Candidate, a State, and a Nation Come of Age.

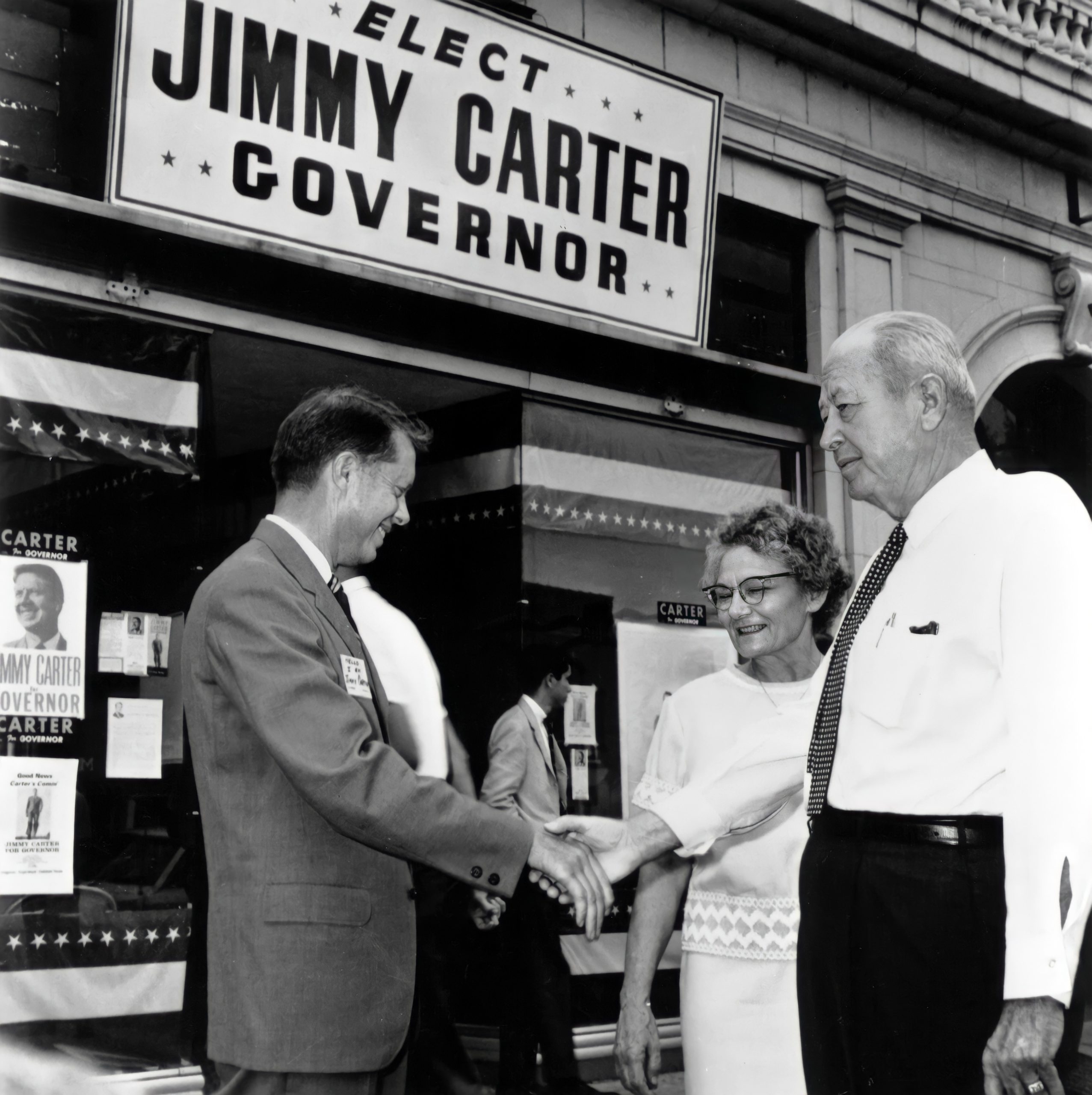

Jimmy Carter lost his first race for Governor of Georgia in 1966, defeated by arch-segregationist Lester Maddox. A period of reflection followed, in which Carter, encouraged by his evangelist sister, Ruth Carter Stapleton, experienced a religious awakening. Until this time, by his own account, he was a “superficial” Christian. Afterwards, he described himself as “born again,” words that many Americans would hear for the first time when Jimmy Carter made his entrance on the national stage.

Four years after his defeat, Carter ran for governor again and won. As Governor of Georgia, Carter worked hard to heal the state’s racial divisions, announcing in his inaugural address that “the time for racial discrimination is over.” It was an unprecedented statement for a Southern governor, but Carter made good on his words. He increased the number of African American state employees by 40 percent and hung portraits of Martin Luther King Jr. and other notable black Georgians in the state capitol. He equalized the funding of schools in rich and poor districts of the state, and created new educational facilities for prisoners and the developmentally disabled. He also streamlined the state’s administration and budgeting procedures, eliminating many government agencies and canceling a number of wasteful and environmentally destructive building projects. Governor Carter’s reputation for efficient administration, combined with his progressive record on civil rights, caught the attention of the national Democratic Party. At the 1972 convention, he made the nominating speech for Senator Henry Jackson.

In 1973, Governor Carter became the Democratic National Committee campaign chairman for the 1974 congressional elections. In the wake of President Nixon’s resignation, and President Ford’s preemptive pardon of his predecessor, the Democrats enjoyed exceptional success in the 1974 congressional election. Barred by the Georgia constitution from running for a second term as governor, Jimmy Carter announced his decision to run for President of the United States. With the 1976 election still two years away, many observers thought Carter’s decision foolishly premature. A flock of better-known candidates crowded the field over the next two years, but Carter steadily lay the groundwork for his campaign, shaking hands and speaking to small crowds across the country. He made a special effort in Iowa, with its first-in-the-nation delegate selection caucuses.

His 1975 autobiography, Why Not the Best?, introduced Carter to a wider public. To an electorate disenchanted with the established leadership of both parties in Washington, Jimmy Carter promised “a government as good and as competent and as compassionate as are the American people.” With his serene optimism, unpretentious manner and engaging smile, Carter began to capture the public’s imagination. After a startling victory in the Iowa caucuses, he defeated better-known candidates in primary after primary, steadily eliminating every possible rival for the nomination. Carter’s Southern origin and unabashed faith were powerful factors in helping him to unite antagonistic factions of his party. He won the Democratic nomination on the first ballot at the party’s convention in New York City’s Madison Square Garden.

The general election in 1976 was a close contest, but most historians agree that the three televised debates between Carter and incumbent President Gerald Ford helped put Carter over the top. Jimmy Carter was the first candidate from the Deep South to win the White House since Zachary Taylor in 1848. At his inauguration, Carter broke with precedent by walking down Pennsylvania Avenue with Rosalynn instead of riding in a limousine, as his predecessors had done. Carter’s down-to-earth style manifested itself in many small ways, such as his insistence on carrying his own garment bag when boarding Air Force One. He continued to teach Sunday school classes in Washington, as he had in Plains, and sent his daughter Amy to a public school in Washington. One of his first priorities as president was to heal a lingering wound of the Vietnam War. On his first day in office, he signed an executive order granting amnesty to those who had evaded the military draft during the Vietnam War, an amnesty that did not extend to deserters.

As president, Carter oversaw a reorganization of several executive branch departments to reflect his domestic priorities. The existing Department of Health, Education and Welfare was divided into two cabinet-level entities, the Department of Education and the Department of Health and Human Services. A new, cabinet-level Department of Energy was created. Throughout his term, President Carter sought to coordinate a national policy of energy conservation to reduce America’s reliance on imported oil. At the same time, he pursued deregulation of transportation, communications, and finance.

Many of the Carter administration’s most noteworthy accomplishments came in the field of foreign affairs. President Carter established full diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China and made good on a long-standing American promise to return control of the Panama Canal to the Panamanians. After negotiating the necessary treaties with Panama, Carter prevailed in an exceptionally contentious ratification fight in the Senate.

The outstanding achievement of the Carter presidency was the peace settlement between Israel and Egypt. Over 13 days of meetings at the presidential retreat, Camp David, Carter persuaded President Anwar Sadat of Egypt and Prime Minister Menachem Begin of Israel to end the 31-year state of war between their countries. Egypt was the first of Israel’s Arab neighbors to make peace with the Jewish state. Israel ended its occupation of the Sinai peninsula and returned control of the territory to Egypt. President Carter later published his reflections on the Middle East conflict in his 1985 book, The Blood of Abraham.

President Carter also negotiated a Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT II) with the Soviet Union, but before the Senate could vote to ratify the treaty, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, and Carter withdrew the treaty from consideration. The two superpowers agreed informally to abide by the terms of the treaty, although neither side ratified it officially.

The 1979 revolution in Iran provided the most trying foreign policy challenges of the Carter presidency. After the victory of a fundamentalist Islamic faction in the Iranian revolution, radical students seized the American embassy and held American diplomatic personnel hostage, while demanding that the United States deliver the deposed Shah of Iran, who had sought medical care in the United States. Even after the Shah’s departure from the United States and his subsequent death in Cairo, the government of Iran refused to return the American hostages. After an unsuccessful attempt to rescue the captive Americans, President Carter was able to secure the Iranian government’s agreement to release the hostages, but not until after he had been defeated for re-election by Ronald Reagan.

After leaving office at the age of 56, Jimmy Carter became the most active ex-president the nation had ever seen. In 1982, he became University Distinguished Professor at Emory University, in Atlanta, Georgia, and in partnership with the university, founded the Carter Center to resolve conflicts, promote democracy, protect human rights, and prevent disease around the world. Since 1989, observers from the Carter Center have monitored more than 70 elections in dozens of countries in the Americas, Africa and Asia.

Former President Carter and the Carter Center have also mediated civil conflicts and international disputes involving Ethiopia and Eritrea, North Korea, Liberia, Haiti, Bosnia, Sudan, the Great Lakes region of Africa, Uganda, Venezuela, Nepal, Ecuador and Colombia. Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter were early supporters of Millard and Linda Fuller, founders of Habitat for Humanity, a nonprofit organization that helps build homes for the needy in the United States and in other countries. President Carter has long served on the board of directors of Habitat, and the Carters themselves have volunteered with the organization for one week of every year. Jimmy Carter has continued teaching Sunday school and is a deacon in the Maranatha Baptist Church of Plains.

Former President Carter’s personal diplomacy helped to defuse international crises in hot spots from North Korea to Haiti. In 2002, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts. Following Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, he was the third American president to be so honored. The Nobel committee cited former President Carter “for his decades of untiring effort to find peaceful solutions to international conflicts, to advance democracy and human rights, and to promote economic and social development.”

Most ex-presidents publish a volume of memoirs or two, but Jimmy Carter has carried on an impressive career as an extremely prolific and successful author. Since leaving the White House, he has published more than two dozen books. In addition to his presidential memoir, Keeping Faith, written shortly after he left office, he has written memoirs of childhood, books on religion, spirituality, aging and family life, a volume of verse, and a historical novel, The Hornet’s Nest, set in the South during the Revolutionary War. One of his most popular and highly praised books is An Hour Before Daylight: Memories of a Rural Boyhood.

Jimmy Carter received both praise and condemnation for his second book on the Middle East conflict, Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid (2006). He recounted his life after leaving office in a 2007 memoir, Beyond the White House, and paid a moving tribute to Lillian Carter in A Remarkable Mother (2008). In Our Endangered Values: America’s Moral Crisis (2005), he returned to the theme of morality in political leadership. From the day he entered public life, his commitment to the ideal of moral leadership has been a consistent theme in his public acts and statements. It has given Jimmy Carter a unique standing among all those who have held the office of President of the United States.

In the summer of 2015, Carter published his 25th book, A Full Life: Reflections at Ninety. A few weeks later he announced that he would undergo treatment for a cancer that had reached his brain. He had first received a cancer diagnosis after having a small tumor removed from his liver earlier in the year. Given the nature of his diagnosis and his advanced age, it might have been expected that the former president would retire from public view. Instead he held a press conference to discuss his diagnosis and treatment. “I have had a wonderful life,” he told the assembled reporters. “I’m ready for anything and I’m looking forward to new adventure.” Recalling his 30-year campaign to eradicate the guinea worm, a parasite that causes untold misery in Asia and Africa, he remarked, “I’d like for the last guinea worm to die before I do.” As to how long he might expect to live, he said, “It is in the hands of God, whom I worship.” On the Sunday following his press conference, he taught Sunday school in Plains, as he had nearly every week since leaving office.

Former President Carter was treated with immunotherapy, specifically a drug called pembrolizumab, which mobilizes the natural immune responses that cancer typically overrides. His response to the medication was excellent, and at the end of his treatment, Carter’s doctors saw no evidence of remaining tumors. Months later, he still appeared to be cancer-free, and news of his complete recovery was made public.

That summer, at age 91, the former president once again donned a hard hat and utility belt and put his well-honed carpentry skills to work, fulfilling his annual commitment to Habitat for Humanity. In 2019, at age 94, he surpassed President George H.W. Bush as the longest-lived of America’s presidents.

On December 29, 2024, Jimmy Carter passed away at his home in Plains, Georgia, at the age of 100. This followed his decision in February 2023 to enter hospice care, after being diagnosed with melanoma in 2015 that metastasized to his brain and liver. His passing marked the end of a century-long life defined by a steadfast commitment to peace, service, and the betterment of humanity.

“Hi, I’m Jimmy Carter, and I’m going to be your next President.”

These were the first words many Americans ever heard from Jimmy Carter. A one-term governor from the Deep South with no Washington experience, professional political observers dismissed his candidacy as the longest of long shots. But the born-again Christian and peanut farmer from Plains, Georgia knew something the experts didn’t. Americans were looking for fresh, untainted leadership to bridge the chasm of mistrust that had opened between the people and their government after the war in Vietnam and the Watergate scandal.

As President of the United States from 1977 to 1981, Jimmy Carter sought to make the United States a force for peace in the world, and made the promotion of human rights a centerpiece of his foreign policy. Over strenuous opposition, he secured ratification of the Panama Canal Treaty, honoring a long-term commitment of the United States to return control of the Canal to the Panamanian people. In the most dramatic achievement of his presidency, Carter personally mediated a peace settlement between Egypt and Israel, ending a 31-year state of war between the Jewish state and its largest Arab neighbor, and laying the groundwork for all subsequent Middle East peace negotiations.

Since leaving office, Jimmy Carter has become the most active ex-president in the country’s history — a humanitarian activist, bestselling author and traveling ambassador of peace, resolving international disputes and helping to monitor elections in newly emerging democracies. The man from Plains, Georgia is still providing the world with the moral leadership he first offered America in the 1970s. In 2002, his commitment to nonviolent conflict resolution around the world was recognized with the Nobel Peace Prize.

One of your greatest accomplishments was the Camp David Accord and the peace treaty between Israel and Egypt. It has become the model for peace settlements between Israel and its other Arab neighbors. What were the conditions that made Camp David possible, and do you see the same conditions present now (1991) that would make possible a broader peace in the Middle East?

Jimmy Carter: Let me answer that last question first. I don’t see the conditions now that were there then.

We had two bold and courageous political leaders then. Particularly Anwar Sadat, combined with a very receptive leader in Menachem Begin, who was willing to make decisions very difficult for him within his own constituency in Israel. And I had done my homework. I had met with the Israeli leaders and the Egyptian leaders, and the Jordanian and Lebanese and Syrian leaders. And so we were able to provide some means by which these two bold and courageous political leaders could come together. They were incompatible. We were at Camp David 13 days. They never saw each other the last ten days. Every time they got in the same room, we went backwards instead of forwards. So Begin and Sadat stayed separate. And I would go to one and then go to the other one, back and forth. And eventually, we came out with the Camp David Accord, which people forget is called “a framework for peace.” It’s a set of principles on which peace can be predicated in the future, and that framework is still absolutely applicable to any negotiations in the Middle East now. The people that rejected it then — the Jordanians, the Palestinians and the Syrians — are now willing to negotiate on the basis of Camp David. We used the Camp David principles six months later to conclude the peace treaty between Israel and Egypt.

Now we have a much more entrenched problem. Although the Knesset, the Israeli parliament, voted overwhelmingly for the Camp David Accords — 85 percent voted for it, 15 percent against it — those 15 percent are the ones that are now in charge of the Israeli government. Although they now profess to be in favor of the Camp David Accords — the withdrawal from occupied territories, the granting to Palestinians of full autonomy, which Prime Minister Begin agreed to do and that the Knesset endorsed — these are the basic principles now on which the Israeli leaders will not agree. But it would be a mistake to give up, because there is a bottom line factor that gives me some hope: the people want peace.

The Israeli people want peace. The Palestinian people want peace. The Jordanians do, God knows. The Lebanese people want peace. It’s the political leaders who are the obstacles, because they are too inflexible, and they are looking at their own sometimes very narrow political constituency to give them restraints which they can’t break. Someday though, there will be leaders there, like Sadat and Begin then, who will truly represent the desire of their people for peace, and then we’ll have success.

One of the other successes that you were involved in is also one of the most controversial, the Panama Canal Treaty. There was a knock-down, drag-out fight in the Senate, but you were successful. The treaty means that the Canal will eventually be turned over to the Panamanians. A lot has happened since that treaty, but none of it has affected the status of the Canal, even though many critics at the time talked about the kinds of things that have happened as being the worst possible scenario.

Jimmy Carter: What people forget is that the original treaty with Panama was written and signed without any Panamanian ever seeing it. It was never fair to the Panamanians, and most people recognize that. President Johnson gave his word of honor to the Panamanians: “We will have a new treaty.” So did President Nixon and President Ford. But it was only when I got into office that I was foolish enough to push it to a conclusion. The treaty is very fair to our country and to the Panamanians. It gives us first priority in using the Canal. It gives us the right to defend the Canal against external threats, not only in this century but even in the next century. And it forms a sharing partnership in operating the Canal. When I was there during the Panamanian elections, which we helped to conduct, I visited the Canal and the American leaders there, and they told me that the Canal was in better shape than it had been in many, many years. Because the Panamanians, knowing that they now have a share in the future of the Canal, were much more enthusiastic in upkeep and maintenance and learning how to be the leaders in ways that they hadn’t been before. This was the worst political battle I ever got into. It was more difficult to get the Panama Canal Treaties ratified by two-thirds of the Senate of the United States than it was for me to get elected president in the first place. It was a very deep and bitter political battle, and many people still haven’t gotten over it. I never go through a week of my life now that I don’t get letters from people condemning the Panama Canal Treaties. Still, and this is I don’t know how many years later. 1978? Thirteen years later. But it was a good thing to do.

It’s surprising that people are still agitated about it.

Jimmy Carter: This is something that many people won’t forget. It is the most courageous thing that the U.S. Senate ever did in its existence. They knew that it was politically unpopular, but they knew that it was right and needed. Of the 20 senators who voted for the Canal Treaties in 1978, who were up for re-election the next year, only seven of them came back. Thirteen of them didn’t come back. And the attrition rate in 1980 was almost as bad. But it was the right thing to do — an all-too-rare demonstration of political courage.

There was one speech that you gave that was also controversial and in some cases misreported. It became known as “the malaise speech” even though you never used that word. You talked about a crisis of confidence that struck at the heart and mind and soul of the national will. Do you still see that crisis in confidence?

Jimmy Carter: In some ways, the situation is different now from what it was back when I gave that speech. I think it was the best speech I ever made, and for the first few weeks, it was a very popular speech. But eventually it was attacked by Senator Kennedy, who ran against me. He said I was talking about the malaise of America, not the bright future of America, and then President Reagan adopted the same concept.

What I pointed out was that our nation had been faced in years leading up to that time with severe challenges and blows: the loss of the war in Vietnam, the assassination of President Kennedy and Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr.; the Watergate scandals, where a president had to resign in disgrace; the revelations that the CIA had deliberately plotted murder. These were blows to our country. But I thought the resilience of our nation was sufficient to overcome that kind of difficulty, and that we needed to look at ourselves and see where is the strength of our country. And the purpose of the speech, I said that we are faced with an energy crisis. We are becoming increasingly dependent on foreign oil; our nation’s security is in danger. It’s not a politically popular thing to do something about this, to save energy, to conserve. But I believed that our country was strong enough to do it. And that was the purpose and the essence of the speech. But the political opponents just took the negative side, that we had serious problems, and characterized it as it never was, as a “malaise speech.” We still suffer malaise in this country, and I’ll use the word this time. But what gnaws at the vitals of our nation are the unsolved problems of juvenile delinquency, teenage pregnancy, school dropouts, drug addiction, homelessness, joblessness. We don’t know in this country the extent of these problems, and we cover our eyes. It’s more convenient not to look at them. I think this country obviously has the ability, as no other nation in the world does, to address those problems successfully. That’s going to be a major part of my own work the next four, five or more years. Just to show that in Atlanta, Georgia, we can marshal all the resources in our community and bring about a simultaneous addressing of these human problems and see if we can do something about them. It’s a kind of thing that is not only an affliction on a nation or in a community, but a wonderful opportunity to show the strength and idealism and benevolence of American people.

After all these years, what are your thoughts, views, and reflections on the presidency?

Jimmy Carter: I would say the main thing is that I didn’t know the complexity of the global problems.

I’m the only president that’s ever visited Africa south of the Sahara Desert. I went to two (African) countries while I was president, and I didn’t know the potential of that continent, nor the challenges that faced those people. Now I do. To a much greater extent I didn’t understand the [widespread] problems in our own country, from a personal point of view. I was dealing with billions of dollars that would be allocated for education or health or welfare or housing, or whatever. But I didn’t know from a personal point of view the people that actually were in need or that were the recipients of those quite often inadequate and ill-designed programs. Another thing was that I didn’t really see as clearly as I should have the perspective of the then preeminent Cold War. I think we could have reached out more to try to form some sort of working relationship, perhaps with people that we looked on then as adversaries. That was a potential there that may not have been adequately explored by me as a president. I’ve also learned since then the wide diversity of characteristics of nations in this hemisphere. We tend to look on South Americans as one kind of people, but I’ve seen that they are just as varied as are the differences, for instance, between the United States and Mexico. There is a tremendous fear of the United States as a dominant superpower that’s always been too ready to send U.S. troops into their nations to act as superior, arrogant oppressors, under the guise of protecting liberty. We invaded Panama recently with what most Americans looked on as a glorious victory. We killed a thousand Panamanians unnecessarily, primarily to arrest the leader of Panama, who had been in bed with our own government, at least the CIA, up until shortly before that. And to us it was a great victory. We defeated Panama. But to the Panamanians, the people who died, it wasn’t. So I see now much more clearly that our country can accomplish its goals, not merely through military action, but through the promotion of peace.

One of the remarkable things about you is that you seem to take the job of former president as seriously as being president itself.

Jimmy Carter: That’s true.

People underestimate the potential of a former president. I happen to be one of the youngest ones who ever survived the office. And the access that I have to world leaders is unlimited. I don’t mean just political and military leaders, but leaders in the field of education or health or agriculture, food production, environment. And so, this is one aspect of it. Also, the influence we have. We can bring together people who have a common goal, like immunizing children or planting trees or solving the starvation problem in Africa, where they’re all working at the same target, but in different ways, and create a team effort that can be enormously more successful than any of them can be working independently. And I have some ability as a former president to dramatize a particular problem, and to reach the news media and therefore reach the consciousness of people.

Another thing I have as a former president is almost total freedom. When I was in office as governor or state senator or as president, I had voluminous responsibilities — the details of government. But now, as a former president, I can pick and choose the things that have a particular interest to me, where I think that my contribution can be uniquely beneficial. I don’t have to worry about the administrative duties of a major job. This makes it not only more fruitful, but also more enjoyable.

It used to be, when I visited the Middle East, for instance, I would fly to Tel Aviv, drive 30 minutes over to Jerusalem, meet with leaders in the afternoon, have a banquet at night and exchange toasts with Prime Minister Begin, or whoever happened to be in office. The next day I was gone to Cairo or Damascus or Amman. Now I go there, I meet with the leaders in all the different parties, and I get immersed in what they think about one another. I meet with the Peace Now people and with the human rights groups, and with the Palestinians in the West Bank, in Gaza, and go to the great universities in Tel Aviv and Haifa and Jerusalem, and learn from scholars who devote their lives to the economic and water aspects, mining aspects, and agricultural aspects of the region. I can immerse myself much more deeply in an individual subject, once I take it on, than I ever could have when I had the multitudinous responsibilities of budgets and dealing with members of Congress, and things in the White House.