Let’s be perfectly honest about this. When I formed Led Zeppelin, I formed it with the idea and ethos that it was going to change music. That’s what I wanted to do, and it clearly did. It clearly did.

James Patrick Page was born in Heston, a suburb of London, but at age eight, he moved with his family to Epsom, Surrey. In the new house, he found an acoustic guitar abandoned by a visitor or a previous occupant. The popularity of Elvis Presley and the British folksinger Lonnie Donegan inspired young Jimmy to take up the guitar. With the aid of a school friend and instruction manuals, he set out to master the instrument, studiously imitating the licks of rockabilly pickers Scotty Moore and James Burton, and blues players Elmore James and B.B. King. The young Page took advantage of the skiffle craze — an up-tempo take on American folk music — to form a band with some older teenagers. At age 13, he appeared with his band on the BBC’s All Your Own program, featuring young people with interesting hobbies. The son of a personnel manager and a doctor’s secretary, Page briefly considered a professional career in science, but music soon took first place among his interests. He played on street corners, in social clubs, anywhere he could find an audience.

After leaving school, Page joined a touring band, Neil Christian and the Crusaders, and made his commercial recording debut at age 18 on the Crusaders single, “The Road to Love.” The teenage Page’s career as a touring musician was cut short by mononucleosis. The recurring infection made it impossible for him to travel, and he enrolled in Sutton Art College to study painting and design. While studying in Sutton, he continued to practice guitar and to sit in with other musicians in London’s burgeoning blues scene. At the Marquee Club, he jammed with the seminal British blues bands Cyril Davies All-Stars and Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated, trading licks with his friends Jeff Beck and Eric Clapton.

Following the international success of The Beatles, Britain’s music scene was exploding. The high expense of session time in London’s limited number of recording studios created an urgent demand for musicians who could learn new songs quickly, create arrangements on the spot, and play without mistakes. Page’s versatility and clean technique brought invitations to record with groups and singers at Columbia and Decca Records. As his health recovered, Page performed with a few touring groups, including Carter-Lewis and the Southerners, but as his reputation spread, he found himself in constant demand as a session guitarist. Setting aside his art studies and live performance commitments, Jimmy Page became a full-time studio musician, playing as many as three sessions a day, six days a week.

Often he was brought in as insurance, in case a less experienced guitarist was unable to complete the recording in the time allotted. He played on the first records of rising groups like The Kinks and The Who and accompanied singers Marianne Faithfull, Petula Clark and Donovan on some of the biggest hits of the era. As he mastered studio recording techniques, he was called on to produce sessions and to serve as an A&R man or talent scout.

In the quickly changing music scene of the era, Page was itching to get out of the studio and try some of the new techniques he had acquired before a live audience. When one member of the pioneering blues-rock outfit The Yardbirds left the band, Page joined up, playing alongside his old friend Jeff Beck. Page recorded one album with the band, toured the United States, and appeared with them in the feature film Blow-Up, but the band had run its course and Page was left on his own to fulfill a series of scheduled concert dates.

Page’s recording sessions and A&R work had introduced him to the best musicians on the scene and he quickly assembled a new group, choosing a team of musical heavyweights to carry out the challenging ideas he had been developing since his studio days. Page recruited the powerful drummer John Bonham, versatile bass and keyboard player John Paul Jones, and an unknown singer named Robert Plant, with a soaring voice and a compelling stage presence. Page’s quartet completed a few tour dates as The New Yardbirds before adopting a name first suggested by The Who’s drummer, Keith Moon: Led Zeppelin.

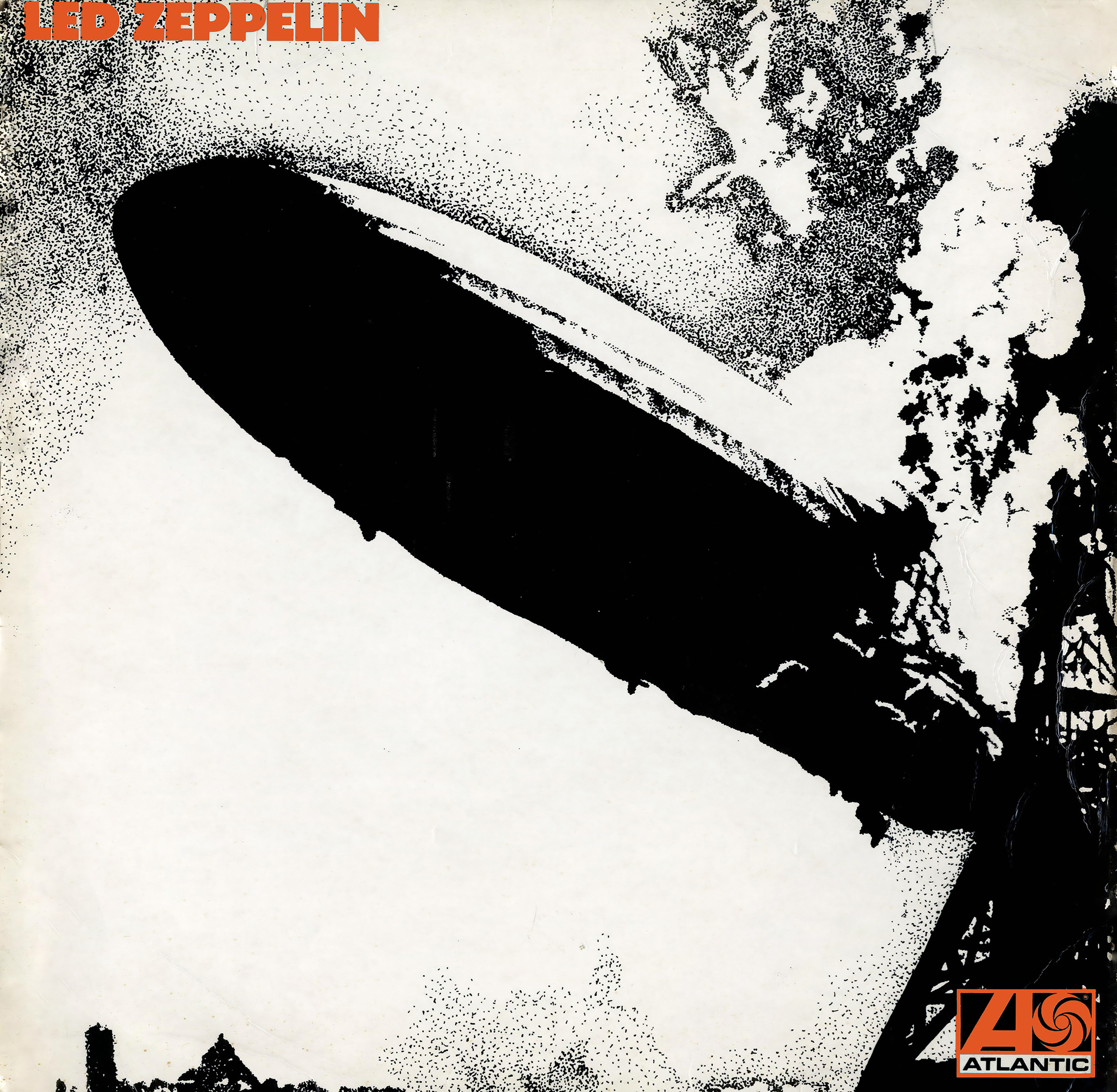

The new group recorded their self-titled debut album in only nine days, with Page producing and assuming the costs of production. Released by Atlantic Records in 1969, Led Zeppelin immediately struck a chord with listeners in the United States. Page had deliberately recorded extended arrangements of his songs to take advantage of the new format of FM radio in the United States. A first American tour drew large crowds, and over the next decade, Led Zeppelin would become the world’s top concert attraction. Led Zeppelin’s deal with Atlantic gave the group unprecedented freedom over what and when to record and perform, as well as control of their album art and promotion. In a departure from standard practice, the next two albums were all called Led Zeppelin and differentiated by Roman numerals, II and III.

While the first two albums emphasized electric blues and hard rock workouts like the hit “Whole Lotta Love,” Zeppelin III (1970) featured more acoustic textures and folk influences. Led Zeppelin’s fourth album — often called Led Zeppelin IV, although the actual package features no title at all — introduced a composition that would become the band’s most enduring classic, and features one of the most celebrated guitar solos in the history of rock, “Stairway to Heaven.”

More record-breaking tours and hit albums followed, including Houses of the Holy (1973) and Physical Graffiti (1975), which features one of Page’s most adventurous compositions, the exotic “Kashmir.” The band’s three sold-out nights at Madison Square Garden in 1973 were filmed. The edited footage was released in 1976 as the concert film The Song Remains the Same.

By 1974, all of the band’s previous albums were in the Top 200, the band had played to the largest audiences ever recorded in both the U.S. and Britain, and were the most popular rock band in the world, eclipsing friends and rivals like The Who and the Rolling Stones. The 1976 albums Presence and In Through the Out Door (1979) were also bestsellers. All nine of the band’s studio albums made the Billboard Top 10, and six were number one bestsellers in the United States.

In the summer of 1980, drummer John Bonham collapsed onstage during a performance in Nuremberg, Germany. Following a rehearsal that autumn, Bonham, who had been drinking heavily, died in his sleep at Page’s home in Windsor. Rather than replace their late bandmate, the group canceled a scheduled tour and officially dissolved. The surviving members of the group have reunited periodically for benefit performances, often accompanied by John Bonham’s son, Jason, on drums.

Since the dissolution of Led Zeppelin, Jimmy Page has engaged in a variety of musical projects, including composing music for the films Death Wish II and Scream for Help. He recorded a new album with Robert Plant in 1984 as The Honeydrippers, and toured and recorded two albums with vocalist Paul Rodgers as The Firm.

Page appeared as a guest artist on records by former bandmates, including Plant, members of The Yardbirds, and with the Rolling Stones. Page and Plant’s acoustic performance on MTV’s Unplugged received the highest ratings in the network’s history. Page and Plant toured to support the CD release of the session No Quarter: Jimmy Page and Robert Plant Unledded.

Jimmy Page has been inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame twice, in 1992 as a member of The Yardbirds, and in 1995 with Led Zeppelin. In 2005, Page was named an Officer of the Order of the British Empire, in recognition of his services to charity. When Page, Plant, Jones and Jason Bonham played a one-night charity concert at London’s O2 Arena in 2007, the venue received 20 million requests for tickets.

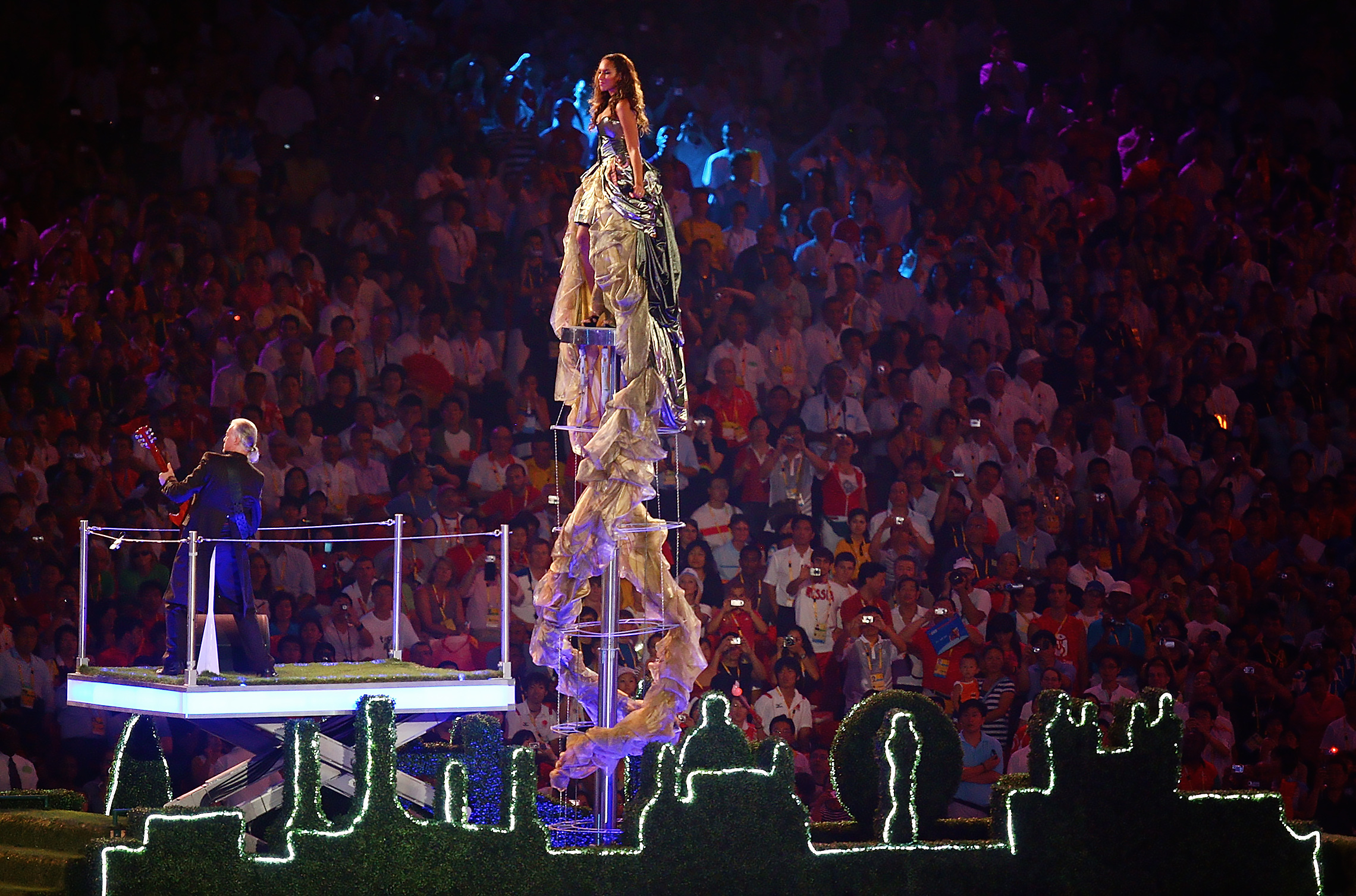

At the closing ceremony of the 2008 Olympic games in Beijing, Page rode into the stadium on a double-decker flatbed truck to play “Whole Lotta Love.” In 2012, Page and his Led Zeppelin bandmates received the Kennedy Center Honors from President Barack Obama in a ceremony at the White House. After more than half a century of making music, Jimmy Page continues to tend Led Zeppelin’s legacy as new generations discover his music and musicians of all ages study and learn from his work to pursue their own musical expression.

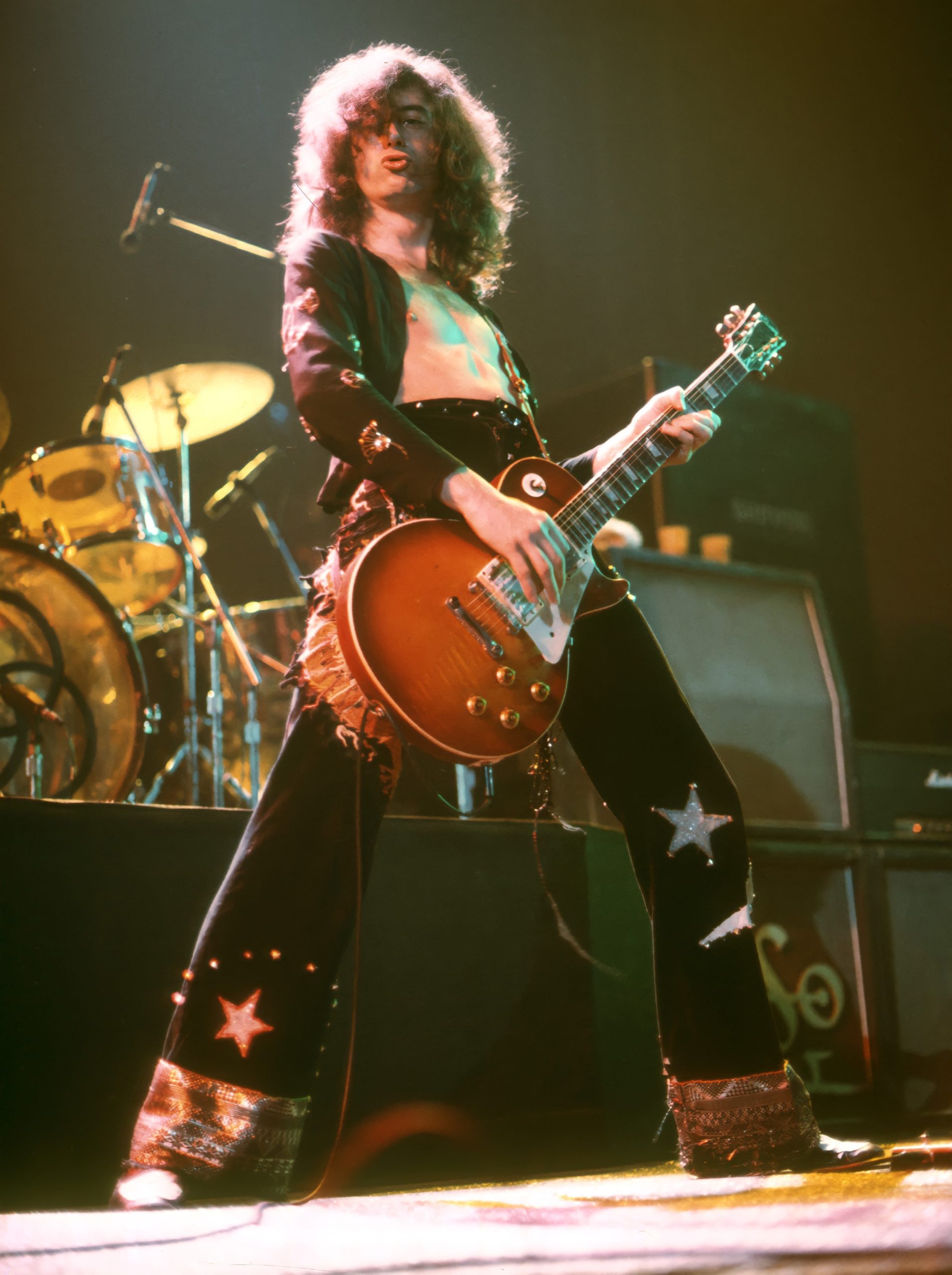

Watch a video of Jimmy Page, one of the most influential lead guitarists in rock, from a 1972 Led Zeppelin live performance of “Immigrant Song.” His solos in “Good Times Bad Times,” “Kashmir,” “Immigrant Song,” “Whole Lotta Love” and “Stairway To Heaven,” are firmly etched in two generations of guitarists’ memories, a “testimony to Page’s compositional and improvisational genius.”

Jimmy Page is the virtuoso guitarist and founder of Led Zeppelin — the swashbuckling hard rock band that set the standard for the many who have followed. Zeppelin may be the most imitated band in the world, and Jimmy Page has been selected as the greatest guitarist in the history of rock music.

A self-taught prodigy who began performing publicly at 13, by his early 20s he was one of the most sought-after session guitarists in London, recording with nearly every major name in British pop and rock. After a stint touring and recording with blues-rock pioneers The Yardbirds, Page set out to create a new group of his own.

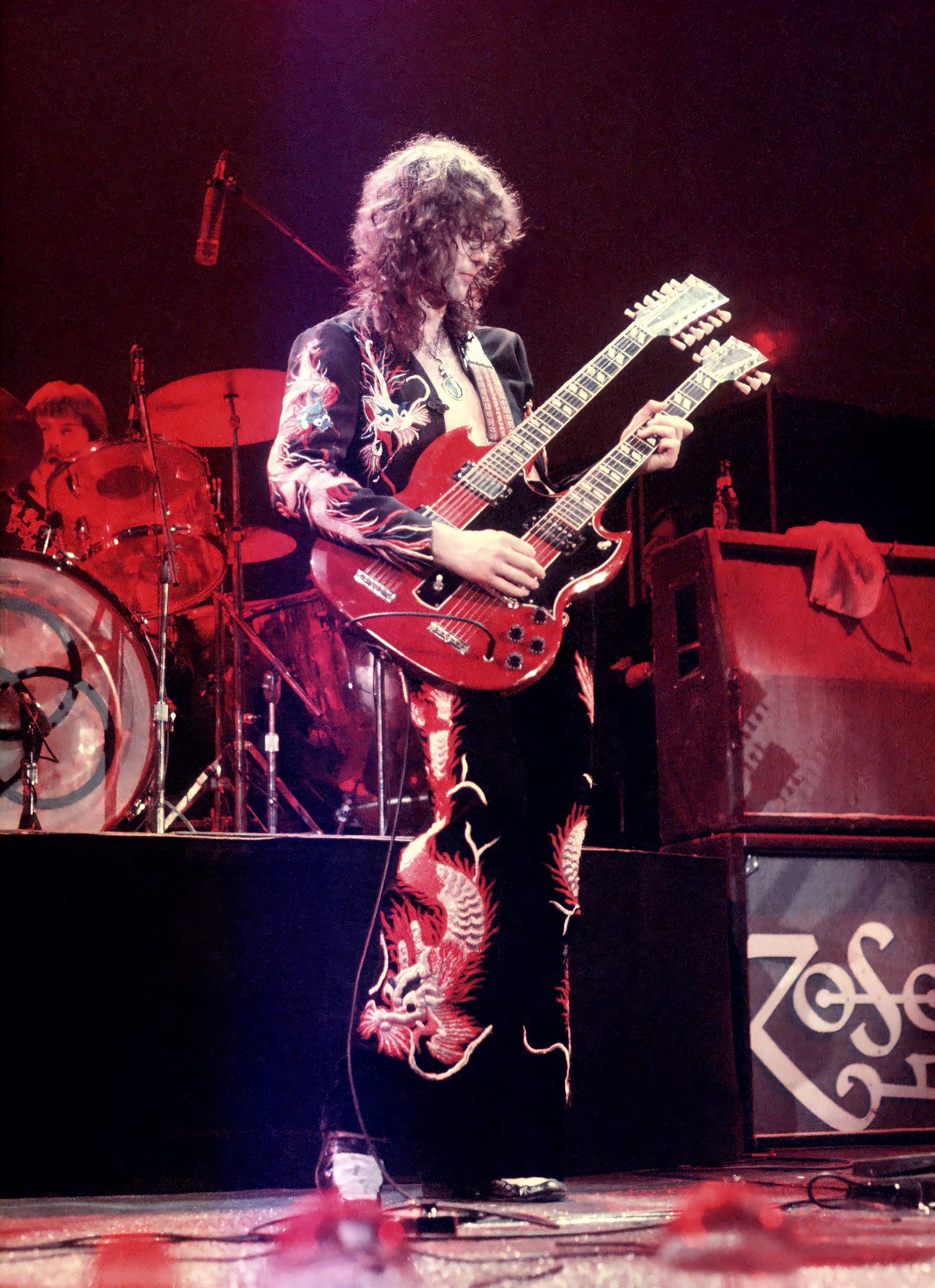

With Led Zeppelin, Page combined electric blues, folk, and rock and roll with his guitar pyrotechnics and innovative recording techniques to create a sound unlike any other. Zeppelin’s incendiary live shows set an unsurpassed standard of musical excitement, and multiple generations of listeners have thrilled to Jimmy Page’s powerful and melodic playing, from pedal-to-the-metal rockers like “Whole Lotta Love” and “Kashmir” to the epic “Stairway to Heaven.”

From the end of the Yardbirds to starting Led Zeppelin, that all happened very fast, didn’t it?

Jimmy Page: The Yardbirds do their last date — I think it’s the beginning of July, and during August I managed to find — yeah, like, the first of July or something — during August, I’ve managed to work — I find Robert Plant, and I work with Robert Plant. I get him to my house, and I play him various ideas of things that I want to do on this album because I had a very clear idea of what would work at that point of time with the FM radio in America. They were just about getting to the point where they were playing whole sides of albums. I realized that if you had an album that had each track almost setting up — as you would listen to one track it would set up the second track because it — there would be such a diversity upon the album of different styles and different moods that it would capture people’s imagination when they listened to it. And now we had the vehicle, with the FM radio, to be able to do that.

So, yeah, I had very clear ideas of the material that I wanted to do, and I’d written Communication Breakdown. I had the whole chart, really, for Babe, I’m Gonna Leave You. And yes, I worked with him, and it was just he and I, and I played him some material that I’d done with The Yardbirds, like Dazed and Confused, and he recommended a drummer. That was John Bonham, and then I’d seen John Bonham play, and I felt him play, actually. It was quite an experience. And he was playing with a musician called Tim Rose, who wrote — he wrote Morning Dew. I think he might have written Hey, Joe, as well, that Jimi Hendrix did. So there were now sort of a possible three, and John Paul Jones heard I was getting a band together and called me out and said, “I hear you’re putting a band together. Would you consider me on bass?” And I said, “Okay, marvelous,” because I had played with him in the studios in various sessions. Robert had had a short time when he played with John Bonham, but John Bonham was off and, you know, playing around and starting to make a name for himself outside of Birmingham. And we just — we had this one rehearsal in a small rehearsal room, not as large as this room even, and we all knew instinctively from that point that we’d never felt anything like that before because it was four musical equals with this sort of communion.

And from that point I got everybody to come to my house and we started rehearsing and recording. And as I say, it’s a very fast route because it’s — Yardbirds break up in July, August rehearsals. We’re actually recording by the end of September, and we’ve done some dates in Scandinavia, which were a handful of dates, but it was good as a team, to be able to play the material live. And we had a set together of other material, as well as our own material so that we could do that in front of an audience before we went in to record. So we could keep the thing really fresh, but any alterations we needed to make we could do, rather than waste lots of time in the studio. And so the first album was done in collectively 30 hours from the time that we went in there and mixed it. So that’s pretty extraordinary!

How did you come up with the name Led Zeppelin?

Jimmy Page: It was a name that Keith Moon had mentioned some time back, and I asked him — or he was talking, you know, about, “Wouldn’t it be fun to have a band called Led Zeppelin?” And I asked him if we could use the name because I was going to be in this band of Led Zeppelin with Keith Moon. So was Jeff Beck. So, yeah, when we were playing in Scandinavia, we were out there as sort of New Yardbirds. It was a cloak of invisibility, really, and even on the first recordings, it said Yardbirds on the box because I didn’t want anybody to know what the name of the band was until we really officially unveiled it. That, basically, the album, was it, but we came over to the United States in — I think it was right on Christmas in 1968. And then we played some concerts, and then we came to the West Coast and played Los Angeles and the Fillmore. And what happened at the Fillmore was that we had an extra night put in, and we just tore it up. We tore it up. The bands that were supposed to be playing there didn’t come, and then we’re sort of jamming, and of course, we had this really hard set, and the whole of the United States got to hear about this group that now had the record out in the early part of January. The record was being played all over the United States, and it was via radio because, of course, there wasn’t cell phones. There wasn’t the Internet. It was the word by radio that this band was just incredible, and as we moved across the United States we — by, say, March, you know, we were on the — maybe even before that, February, March — we were on the East Coast from the West Coast, and people were just coming and just coming to see us.

It was incredible because the reception was amazing, and it was incredible, but here comes the interesting thing, was that from that point onwards we were never able to satisfy the demand of people that came to see us. We would all — and we were doing multiple shows in cities, and we would still just sell out, sell out over all the years that we played, so that was pretty good. Pretty good sort of CV, really.

That time —1968 — was such a tumultuous year in the United States. How do you think the times influenced your music?

Jimmy Page: I remember being with The Yardbirds and passing the hotel where Martin Luther King had been at that time that he’d been assassinated. He’d stayed at the hotel, and the times were so — was such an upheaval, and it — and there was so much with the loss of the Kennedys as well, you know? That suddenly it was just becoming — it was becoming serial — on the serial nature, and it was just so distressing for the people of the time that had so much hope. And I must say it was — there were mixed audiences. I can tell you that much. That there were mixed audiences, black and white. You’d see the number of black people come to the concerts. Once Martin Luther King got shot that changed. That changed. You didn’t see it so much.

There had been such a positive movement. I know we can all laugh about the Flower Power movement but peace and love was certainly something that we could all benefit by and live by, that’s for sure, and the protests for the Vietnam War were profound, absolutely. How it affected the music was you were a product of the times at that time. Now as far as the music went at the time…

I wanted to make something which was really new insomuch that there would be four superstars in the band that they — if you listened to the records you would be able to listen to it and then — playing as an ensemble — or you could listen to it and just listen to what the drummer is doing. Or you could just listen to what the guitarist is doing, or the bass, or the keyboard, or the vocals. You can just appreciate exactly what that input is because it wasn’t just one superstar with a collective. This was exactly what I wanted to do, so the music will actually work at counterpoint. And that’s exactly what it was. So it was something — within the music something really new, something for people to be able to enjoy and connect with because in those days that’s what people had, was their music. They really — it wasn’t like things are today. They didn’t have so many things to amuse them, but music was what they really followed and what they really enjoyed. That was their release, and also, if a band — if they followed a band and the band was to fragment and one member would have a band over here, another over here, then they would follow them, and they would — you know, it was really, though — and so that was very helpful for me because with The Yardbirds I’d built up of a cult audience as a guitarist, you see.

It was interesting because over here (in England) it was slow because we spent a lot of time in America. Because once that door — just sort of a glimmer of light behind that door opening, we sort of pushed it open and went in. And you were allowed to sort of — you were allowed to perform and play and be in America for up to six months in a year, but not beyond. So as we all know, it’s a massive continent, and we spent as much time as we could sort of, you know, trying to play in all manner of states.

How did it feel to walk on stage in those days?

Jimmy Page: Certainly within the vehicle of Led Zeppelin there was so much improvisation that was employed within the framework of a number, and our sets went from — well, in those early days they were maybe an hour, hour and twenty minutes, to three hours, three-and-a-half hours, because we were jamming and we were making up music there and then on the spot, and — because the thing about the band was that you would have to be listening all the time to what everyone else was doing. So if I was to take a different shift, a different route on the guitar, they’d be with you like that, or if Robert was going to sort of sing — if you were going into a quiet passage and Robert would start singing something, you’d be straight with him on it with something that was new and you — new chord structures, and it was pretty — a pretty extraordinary thing. So it was — there were frameworks to numbers, but there were whole areas for improvisation. So prior to going on the stage you’d have to be very focused so that you could really — especially if it was starting with something like Song Remains the Same, which is a pretty testy song, and yeah, you’d need to be very focused to go on and kick off with something like that, but as I may have mentioned before, you wouldn’t know what was going to happen within those three hours because so many things would come up. And you wouldn’t necessarily remember everything that had gone on either, so it was pretty good. There were so many bootlegs that I managed to listen to with all these different concerts because there were — some of them really dramatically different from night to night, to hear just exactly how marvelous we were.

The image of rock musicians, especially in that era, is people taking enormous amounts of drugs all the time. Was it like that?

Jimmy Page: Well, unfortunately, we lost a lot of people, didn’t we, along the way. It was a sort of party time during the ’60s, that’s for sure, but it was pretty innocent, really. Although there were darker elements around, but I think we managed to steer clear of those things.

Jimmy Page: The thing about the music was that was it. That was the intoxicant of the whole thing. It was something purely for the fact that if you’re playing for two-and-a-half hours, three hours, sometimes three-and-a-half hours, you’d build up so much adrenaline from that, that when you’d come off stage you couldn’t possibly just go home and sort of go to bed. So you would go out and you’d go to sort of maybe clubs or whatever, just to sort of start stabilizing again. So really the intoxicant was the music. There’s no denying that.

How do you take care of yourself in that kind of situation?

Jimmy Page: How do I take care of myself? Well, let’s see, I don’t drink alcohol. I think that makes quite a difference because it got to the point where I was in my 50s and I thought, “I’ve got a shot of getting to my 70s here if…” I wasn’t drinking alcohol to any excess, but I did — but I thought it was a good idea to stop drinking, and so that’s a good number of years ago now. And — yeah, and I used to smoke cigarettes, and I stopped smoking cigarettes, and so that was a bit of a sort of maintenance plan for the future! Actually, people drink in a totally different way now. They certainly do over here anyway (in England), unfortunately, to what we used to drink like when we were teenagers and in our 20s. But hangovers were sort of non-existent in your teens because you really didn’t drink very much, and then maybe when you were in your 30s you’d get a hangover, which would go into the following — start the following morning, and as the decades go by you’d be aware that if you’d had a sort of night of drinking it might even go into a second day. And I thought I didn’t enjoy that. I didn’t like the idea of either having a drink or being — having a hangover and effects of it, and I just gave up on that idea.

Led Zeppelin didn’t play many concerts after 1980, but one of the concerts that we played was actually ten years ago this December, in 2007 at the O2, and that was with the son of John Bonham playing the drums, and John Paul Jones himself, and Robert Plant. And that was an interesting concept because it was — we played for about two hours and twenty minutes, so it was still in the tradition of long sets. Not three-and-a-half hours, two hours and twenty minutes, and of course, you go on and you have to remember everything that you’re going to do, and you also need to have that — those areas where you can have free improvisation because it had to be true to the spirit of what the adventure was about in the first place. But no, I played that totally sober, just an example.

How did you go about writing, or creating, music? How do you foster creativity?

Jimmy Page: Well, there’s no one size fits all on this. For example…

Jimmy Page: Pretty much most of the time, if I wasn’t touring with Led Zeppelin, I would be working at home on the guitar. And I’d be working on pieces of music that I would sing and direct towards the next album — that would be recorded when that would come. And I had one piece of music that was an absolute epic, and I’d overlaid sort of bass and electric guitars. It was an acoustic guitar we used to start with, and a Mellotron, where — a Mellotron would allow you to play, on a keyboard way at the time, string sections and brass, etcetera. And I had this piece, and it was really quite ambitious at the time. And right at the very end of all this guitar noodling, there was this phrase, and it went [humming “Kashmir” phrase], and I thought, “That’s really wonderful. All this other stuff that you can — but that — that’s really interesting.” And so I started to play it, and I realized that you could play it in this sort of metric fashion, and it was almost like a round, where it would come ’round upon itself, and the — that first phrase — because it’s back to front from the way that it is on the record. I thought that, if that is played over this sort of metric riff with this cascading — and I thought at the time, brass — it’s going to be really interesting. And it’s “Kashmir,” of course. So — and I thought of that. I thought of that and its sort of — the density of it, and the — well, we’ll say the depth of that because the density comes more into something like “When the Levee Breaks.” That’s something which is really dense. But I visualized it with orchestra, right? So, yeah, I could see it and I could hear it. I could hear it.

I think “When the Levee Breaks” is something which is really — it was groundbreaking at the time. I think the very first album of Led Zeppelin was — it changed everything, really, and the way that people recorded. Then they were — then they went into the world of ambient recording, yes, and the first album was full of so many ideas that hadn’t been done before. So that was — that has to be said that that’s on the top of the list, really, because without the first album there wouldn’t have been a second album.

Has music taken you places that you never thought you would go?

Jimmy Page: Let’s be perfectly honest about this. When I formed Led Zeppelin, I formed it with the idea and the ethos that it was going to change music. That’s what I wanted to do, and it clearly did. It clearly did, and it brought to the forefront these master craftsmen that were involved in that band. The interesting part of it all is that here I am, and here I am now. I was 24 when I formed that band. I’m 73 now, and the lifetime achievement of it is the fact that even from the time that that first album came out, even though I’ve been a studio musician and played on countless records and albums of a myriad of artists, and I’d played in The Yardbirds and did good work, but…

Jimmy Page: The amount of people that I’ve met throughout my life, from the age of 24, that said that Led Zeppelin music has meant so much to their lives. And that’s a wonderful thing, a remarkable thing, to know that you’ve — that you made a difference in people’s lives. But not only that. In parallel with that is the young musicians who I’ve been impressed by, the production techniques, by the guitar playing and the various styles of guitar playing, by the songwriting, and they’ve been inspired to be musicians themselves. And that’s a wonderful legacy to have, to know that you’ve been able to do something which has made a change, something which was your hobby, something which was your passion, something which you believed in all the way through and you wouldn’t deviate from it. But the thing that you believe that you had to do is keep making an improvement on your own personal performance and what you could do in expanding the whole horizons of everything.

There’s so many different examples of that, and that’s very difficult to actually convey because it — I think music is something that you actually experience. You feel it on an emotional level as much as an intellectual level, but in a way it needs to be — it’s good to actually hear the music, to be able to give examples. But I know I’ve — I know instinctively that the various construction that was used in the music of Led Zeppelin, the sort of — like, example, a song like Babe, I’m Gonna Leave You or Ramble On, has got, like, the acoustic guitar, and then it comes in through a full ensemble, a chorus — which you people would refer to that as a power chorus. Well, I know bands in the 1980s were using that technique. The whole approach to it, the whole taste that was employed, I think, has had a lot of appreciation.

Everyone has copied what you were doing. It was instantaneous.

Jimmy Page: Yeah. Well, I don’t know whether they copied it, but I learned records when I was a teenager, and so I wasn’t necessarily copying them, but I was learning, almost like an academic. I was learning, and then I was sort of recreating what they did. But then I started to try and do things in the spirit of what that was, or within that Chicago movement of the ’50s. That sort of thing, those sort of riffs that they did. It’s not necessarily copying, but people can definitely use it, the work that I’ve done, or that Led Zeppelin did. It’s a textbook, and it’s a jolly good textbook at that. So you don’t have to get the book Play in a Day now. You just can source it on the Internet.