When you write, you’re always revealing a difficult part of yourself.

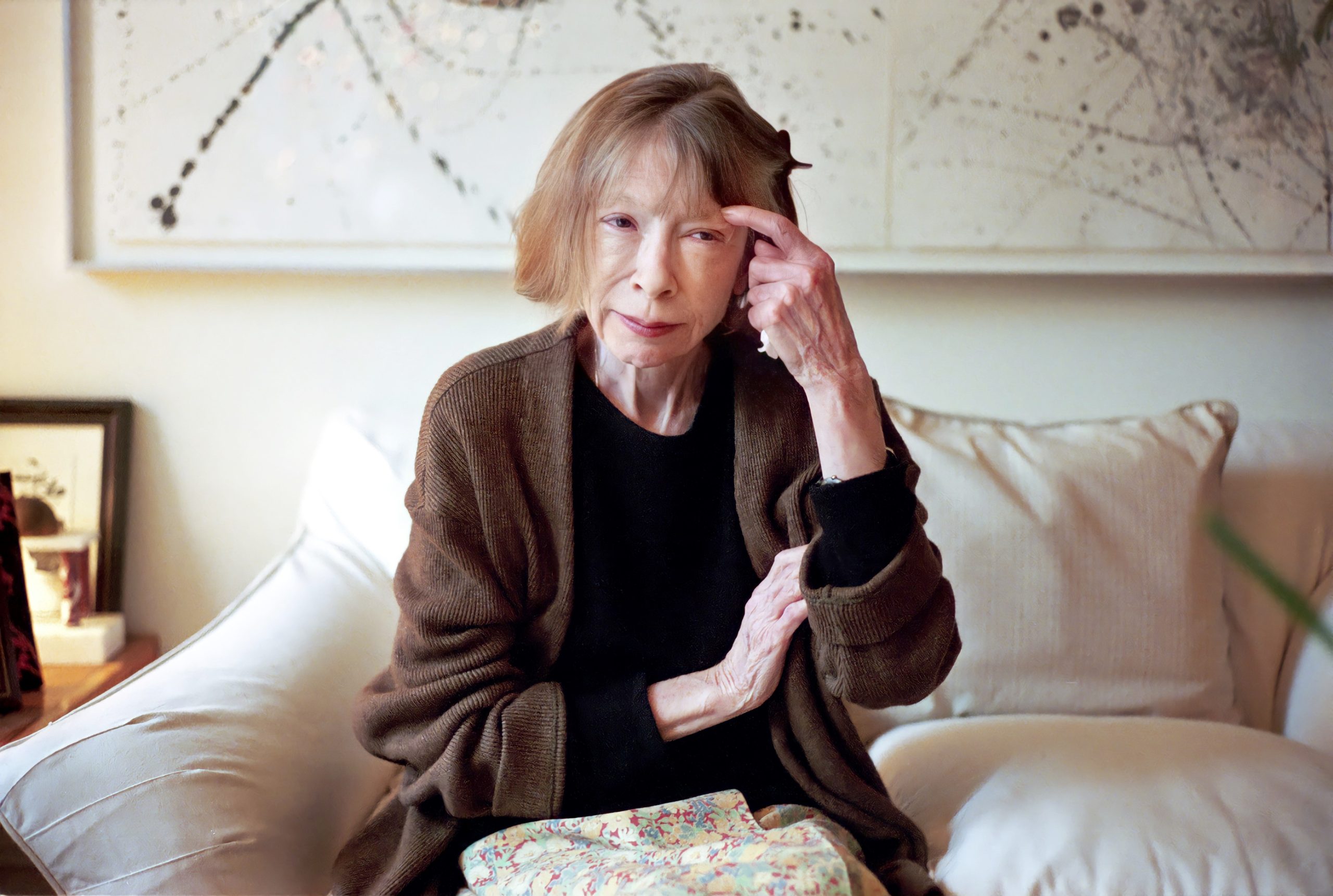

Joan Didion was born in Sacramento, California. Didion spent most of her childhood in Sacramento, except for several years during World War II, when she traveled across the county with her mother and brother to be near her father, who served in a succession of posts as an officer in the Army Air Corps. Her family had deep roots in the West; family tales of pioneer days informed her first novel, as well as her later memoir, Where I Was From.

By her own account, Didion was a shy, bookish child, although she also pushed herself to overcome her shyness through acting and public speaking. In her final year at the University of California, Berkeley, she won an essay contest sponsored by Vogue magazine. The first prize was a job in the magazine’s New York office. Didion remained at Vogue for two years, progressing from research assistant to contributing writer. At the same time, she published articles in other magazines and wrote her first novel, Run River (1963). Although the novel sold poorly, it attracted favorable reviews, and she was offered a contract to write a second book.

In 1964, Didion married John Gregory Dunne, an aspiring novelist who was writing for Time magazine. The couple moved to Los Angeles with the intention of staying six months, and ended up making their home there for the next 20 years. The pair adopted a baby girl they named Quintana Roo, after the state on the eastern coast of Mexico.

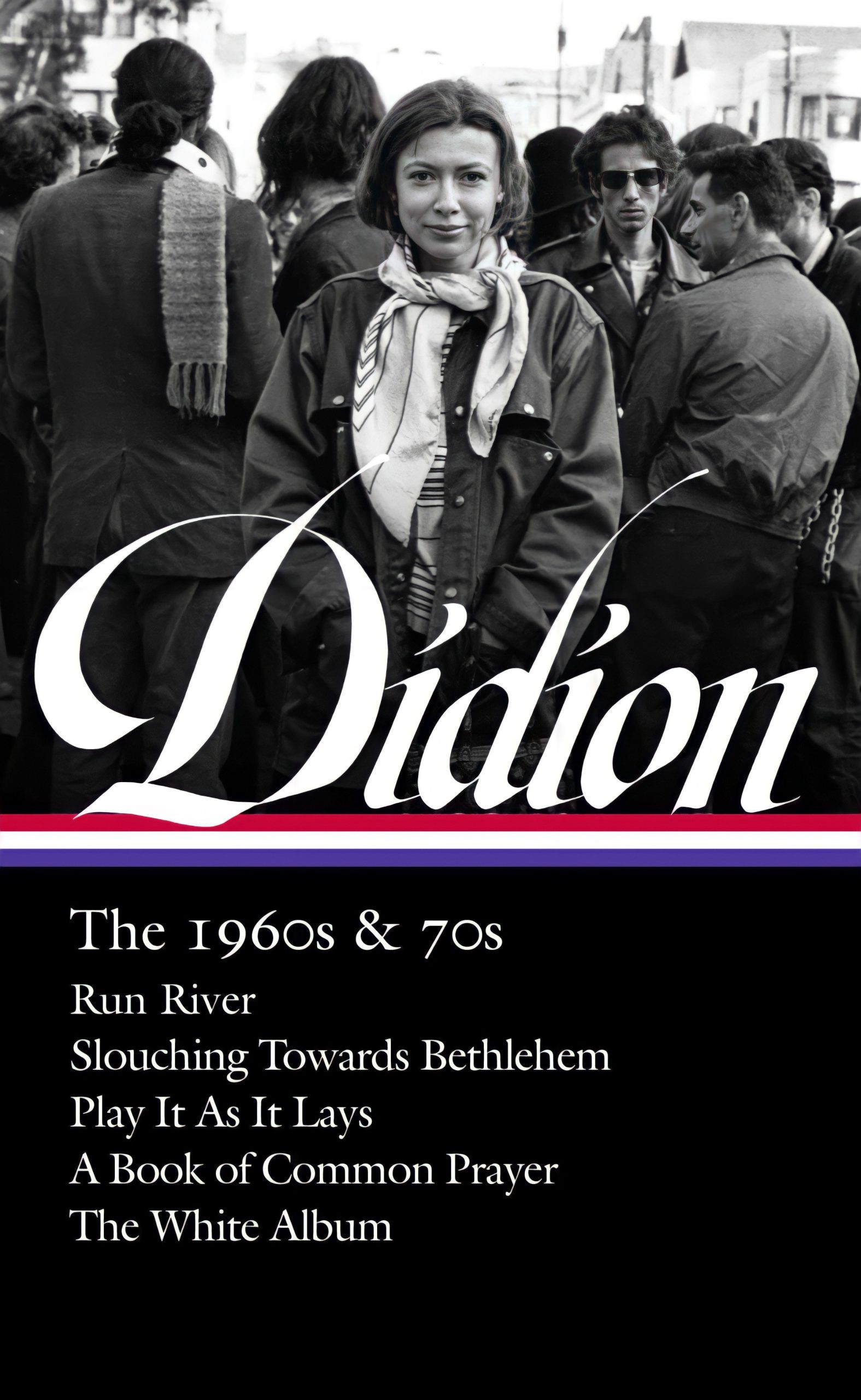

The atmosphere of California in the 1960s provided Didion and Dunne with ample opportunities for writing in the personal mode that was becoming known as the New Journalism, also associated with the writers Norman Mailer, Tom Wolfe, Hunter Thompson and Gay Talese. Didion’s essays on the ’60s counterculture were collected in the volume Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968). Published to critical acclaim, the book is one of the signature works of the decade. Didion’s second novel, Play It As it Lays (1970), set among aimless souls adrift at the edges of the film industry, captured a mood of anomie and alienation that crept over the film colony at the decade’s close.

Working in collaboration for the first time, Didion and Dunne wrote the screenplay for the film Panic in Needle Park (1971). Set among homeless drug addicts in New York City, the film introduced film audiences to the actor Al Pacino. Their work on the film was much admired, and the pair would become one of Hollywood’s most sought-after screenwriting teams, a lucrative sideline to their journalism and fiction. Among the many screenplays they wrote together, the best known are screenplays for the film adaptation of Play It As it Lays (1972); the 1976 remake of A Star Is Born, featuring Barbra Streisand and Kris Kristofferson; the film version of Dunne’s novel True Confessions (1981); and Up Close and Personal (1996) with Robert Redford.

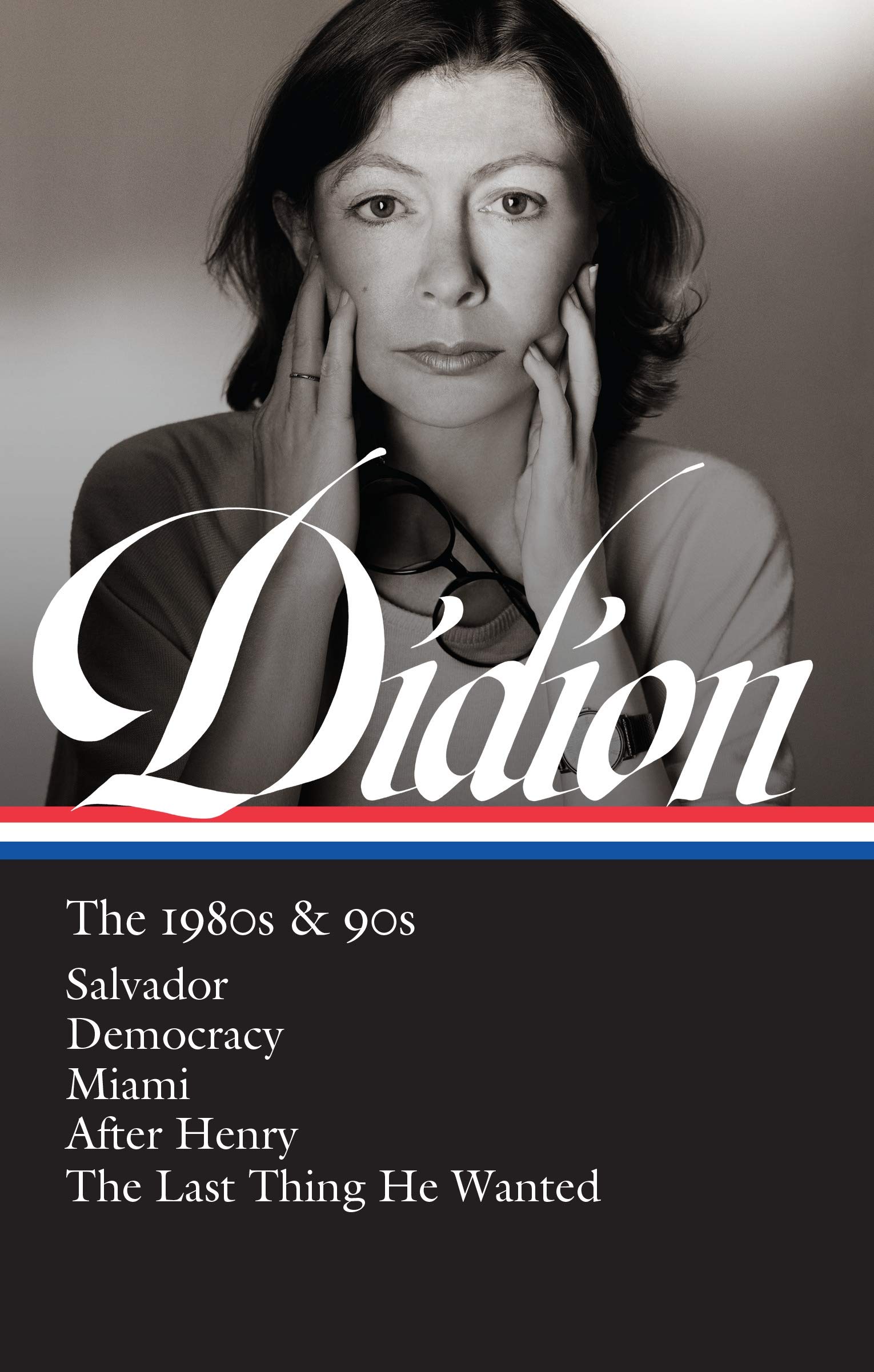

Didion published a second volume of essays, The White Album, in 1979. She had won a national reputation as an intensely acute social observer and prose stylist; her voice was admired for its gemlike precision and elegance. In the 1980s, Didion’s interest turned to the state of her country’s relations with its southern neighbors, examined in two book-length essays, Salvador (1983) and Miami (1987). Travels in Central America and the Pacific also provided the background for novels of political intrigue, including A Book of Common Prayer (1977), Democracy (1984) and The Last Thing He Wanted (1996).

Over the years, Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne often found themselves in the position of explaining New York to Californians, and California to New Yorkers. In the mid-1980s, the couple moved back to New York City. Many of Didion’s observations of the city appear in her essay collection After Henry (1992). Years of Didion’s essays on American politics and government were collected in the volume Political Fictions (2001). Her thoughts turned back to California in Where I Was From (2003), a wide-ranging volume of reflections on California’s past and present. Her first seven books of nonfiction have been collected in a single volume, We Tell Ourselves Stories in Order to Live.

In late 2003, Didion’s daughter, Quintana, fell gravely ill. Shortly after returning from a visit to their comatose child in the hospital, her husband, John Gregory Dunne, suffered a fatal heart attack. Joan Didion wrote a searing account of her journey through grief in The Year of Magical Thinking. At the time she finished the book, her daughter appeared to be recovering from her illness, but by the time the book was published, Quintana had died. The Year of Magical Thinking was published to widespread acclaim and received the National Book Award for Nonfiction in 2005.

In her first foray into writing for the theater, Didion adapted The Year of Magical Thinking to the stage. The Broadway production opened in 2007 and starred Didion’s friend Vanessa Redgrave, who repeated the role at Britain’s National Theatre. The play has since been performed throughout the English-speaking world, and in French, Spanish and Norwegian translations. Didion continued to document her experience of personal loss in the 2011 memoir Blue Nights, which directly addressed the death of her daughter, among wide-ranging observations on childhood, motherhood, grief, mortality and the aging process.

In 2013, President Barack Obama awarded Joan Didion the National Medal of Arts. She is the subject of a feature-length documentary film, directed by her nephew Griffin Dunne. The film, The Center Will Not Hold, premiered on Netflix in 2017. The same year saw the publication of a book of earlier travel essays, South and West. In 2019, Library of America began republishing all of Didion’s novels and books of essays in a collected edition, beginning with Joan Didion: The 1960s and 70s. Let Me Tell You What I Mean, a volume of Didion’s previously uncollected essays, drawn from the years 1968 to 2000, was published early in 2021. Library of America’s second volume of Didion’s collected works, Joan Didion: The 1980s and 90s, appeared in April 2021. Joan Didion died on December 23, 2021, in New York City. She was 87.

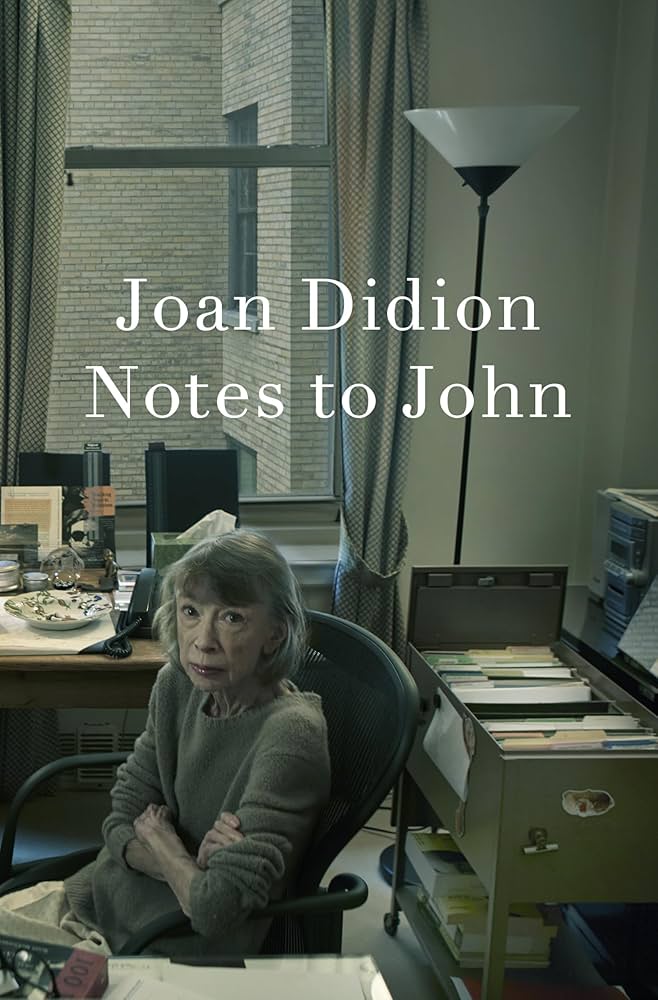

In 2025, a posthumous work added a final dimension to Didion’s body of writing. Notes to John draws from a private journal she began in November 1999, when she sought psychiatric help during a difficult period for her family. Addressed to her husband, John Gregory Dunne, the journal records her sessions with the psychiatrist over more than a decade. Initially focused on alcoholism, depression, anxiety, adoption, and the complex relationship with her daughter, Quintana, the notes later turn to her work, her childhood, her habit of anticipating catastrophe, and her reflections on legacy—“what it’s been worth.” Unshaped for publication, Notes to John offers an unusually intimate record, written in the same precise, unsentimental voice that defined Didion’s work.

Since the 1960s, Joan Didion has been one of America’s finest novelists and most acute social observers. As an undergraduate at Berkeley, she won an essay contest sponsored by Vogue magazine and was offered a job in the New York office of the magazine’s publisher, Condé Nast. In New York, she met her husband, the novelist John Gregory Dunne.

The couple moved to Los Angeles, where they enjoyed a unique partnership as Hollywood’s most sought-after screenwriting team. The Hollywood scene and the California counterculture provide the backdrop for her novels of the 1970s: Play It As it Lays and A Book of Common Prayer. Her reflections on the turbulent era appeared in her bestselling essay collections, Slouching Towards Bethlehem and The White Album. She won a devoted audience and the profound admiration of her peers with her immaculate prose and penetrating eye for the revelatory detail. In the 1980s, she broadened her range with provocative explorations of hemispheric politics in the book-length essays Miami and Salvador. In Where I Was From, she explores her memories of childhood in the Sacramento delta, and how history and experience have altered her view of her native region.

Her memoirs, The Year of Magical Thinking and Blue Nights, unflinchingly describe her response to her husband’s sudden death and the fatal illness of their only child. From the depths of grief, Joan Didion has risen to the height of her powers and turned unbearable experience into transcendent art.

You were working at Vogue magazine when you wrote your first novel. Did you always see yourself as a novelist?

I did see myself as a novelist, even though I was having trouble finishing this first novel. After it was published, it was only read by about ten people, but they happened to be ten people who gave it to ten other people and eventually — you know, not only was it not a commercial success, it wasn’t by any means, I don’t think, a success on its own terms. I didn’t know how to do it, and it ended up, because I didn’t know how to do it — I wanted to have a shattered narrative, but I didn’t have a clue how to do that, and so it was confusing. So the publisher pressed me to straighten out the chronology, so it became just a simple novel with a flashback, which wasn’t my intention at all. But anyway, enough people read it so that I was offered a contract for a second novel.

What was the first novel called?

Joan Didion: Well, that was another thing. It was called Run River, but that was the publisher’s title. I said, “What does it mean?” He said, “It means life goes on,” and I said, “That’s not what the book is about.”

And what was the second book?

Joan Didion: The second was Play It As It Lays.

You’ve said that one of your intentions in that work was to write a novel that moved so fast that it would be over before you noticed it, so fast that it would scarcely exist on the page.

Joan Didion: I just wanted to write a fast novel. You always have a vision of what kind of object a piece of fiction is going to be, or anything that you’re making. In that case, it was going to exist in a white space. It was going to exist between the paragraphs. Some of the chapters are only three or four lines long in that book, and I found a way to speed it up. I had started it — just because I didn’t know how else to start it — I started it with two or three characters (who) have short first-person statements, and then it goes into a “close third” for what appears to be the rest of the book, but as the book comes to an end and starts gaining momentum, you can pick up a lot of momentum by going back to this device from the beginning. This sounds so technical. You go back to that first person and shorter and shorter bursts, and it really gives you a lot of speed. So I was sort of thrilled with that.

It was a fairly revolutionary structure, wasn’t it, to employ both third- and first-person narrators that way?

Joan Didion: There is nothing you can’t do, it turns out.

Faulkner, in As I Lay Dying, used all these different first-person narrators, but you mixed that up even further by having first and third-person narrators. When you say you wanted the book to move fast, do you mean you want the reader to kind of gobble it up?

Joan Didion: I always want everything read in one sitting. If they can’t read it in one sitting, you’re going to lose the rhythm of it. You’re going to lose the shape of it. I myself love to read those Victorian novels which go on and on, and you don’t read them in one sitting. You might read one over the course of a summer, but that isn’t what I want to write.

To this day, your books are fairly short, for the most part. Did a publisher ever give you any trouble about that?

Joan Didion: No. Publishers now, it turns out, like short books. They didn’t used to like short books, but they are now convinced that that’s what people want.

I would imagine that it’s harder to write a short book because every word has to be so exact. Isn’t it easier to write long?

Joan Didion: It might be for some people, but it wouldn’t be for me because I would lose interest as it kind of meandered on.

Could you tell us about how you met John Gregory Dunne and how you came to work together as a team?

Joan Didion: We were friends for a long time before we decided to get married. I met him, he was working for Time. He was writing foreign news for Time, and he was just someone I liked and he made me laugh, and we would occasionally have lunch. We had friends in common. Then, for some reason — I don’t remember exactly why — but one night we had dinner. He said he was going to drive to Hartford the next day — he was from Hartford — did I want to come up, and I said sure. So I went up to Hartford, where his family lived, and I was so taken with this entire family that we started seeing each other in a more serious light. Really, at that time, he was, as I said, working for Time. I had published one novel. Neither one of us was very well established, and we went to California and started supporting ourselves by writing pieces. So that required one or the other of us — me to read his pieces, him to read my pieces. So we began to trust each other as first reader.

At what point did you and your husband first collaborate on something together?

Joan Didion: We didn’t collaborate until we wrote a screenplay, which I think was 1969. We did Panic in Needle Park. That’s all we ever collaborated on was screenplays.

Did that change the balance of how you worked together as editors?

Joan Didion: No, because it was a totally different activity.

And also because you were dealing with a studio? As in A Star is Born?

Joan Didion: You’re always dealing with somebody else. Yes.

We did A Star Is Born in 1972 or ‘3, yeah. That movie was actually John’s idea, because it was conceived as a rock-and-roll remake of A Star Is Born. The names that came to mind were not necessarily the names who were going to be in it, but it was just two faces. It was Carly Simon and James Taylor, and Warner Brothers picked this up right away because they had a lot of music, so they got the idea. They had Warner Brothers music. So it was very easy to set up a contract, and Warner Brothers set up so we could do the research. We went out on tour with bands that summer and then wrote the screenplay, which we had a lot of fun doing because it was totally research. It was fun. You’d find yourself in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, on a summer night with a really bad English metal band — you know, I mean just hopeless — and being really thrilled. Then it got to be heavy weather on that picture because the question of casting came up, and it turned out to be a lot of other personalities involved.

As writers, you don’t have that much control in movies.

Joan Didion: You don’t on a movie, no. Never.

There are so many different aspects of California life in that era that come up in your writings. One that stands out is the Manson murders and how they jolted the town from its previous state of self-satisfaction or complacency. Could you tell us about that?

Joan Didion: What struck me about the Manson murders was how at the moment they happened, it seemed as if they were inevitable. It seemed as if we had been moving toward that moment for about a year.

There were a lot of rumors about stuff, a lot of stuff going on around town, which you would kind of hear about on the edges of your mind and not want to know any more about. After the fact, it was kind of amazing to see how many lives had intersected with the Manson Family’s. I can remember we had a babysitter from Nayarit then, and she was very frightened on the night of the murders, or the afternoon when we heard about the murders, and I assured her, “Don’t worry. It has nothing to do with us,” but it did. It had to do with everyone. Then later I was interviewing Linda Kasabian, who was the wheel person — she wasn’t the “wheel man,” she was the “wheel person” — for the LaBianca murder. I can’t remember. Maybe also for Tate. But anyway, the night they did the LaBianca murder, they were driving along Franklin Avenue looking for a place to hit, and that’s where we lived, and we had French windows open, lights blazing all along on the street.