I love telling lies. I love making stories. I love interpreting the world. It’s why I started to write, you know, to interpret the world to myself because I didn’t understand it. I found it baffling.

John Banville was born and raised in Wexford, Ireland, the youngest of three children. By Banville’s account, the household was not a literary one, but both his brother Vincent and his sister Vonnie also became writers. As a boy, he enjoyed adventure stories, but when he was 13, his sister gave him a copy of James Joyce’s Dubliners. Joyce’s gemlike tales of his native city gave the young John Banville his first intimation that compelling fiction could be drawn from the materials of everyday life. Inspired by Joyce’s example, Banville wrote stories throughout his teens, as he progressed from a Christian Brothers primary school to St. Peter’s College secondary school in Wexford. The young Banville considered becoming a painter or an architect, but after a false start studying architecture, he decided to forgo further formal education and took a job as a clerk with Ireland’s national airline, Aer Lingus. The work held little interest for him, but he was eager to leave home and see the world, and the airline offered its employees a generous discount for air travel. Banville took advantage of the opportunity to travel to Paris, Rome, and Athens, collecting impressions and experiences he would later use in his fiction. Traveling in the United States in the late 1960s, he was drawn to the cultural ferment of San Francisco and Berkeley, where he met Janet Dunham, a young artist studying at the University of California. Banville stayed in the San Francisco Bay area for two years. He and Dunham were married, and she returned to Ireland with him in 1969.

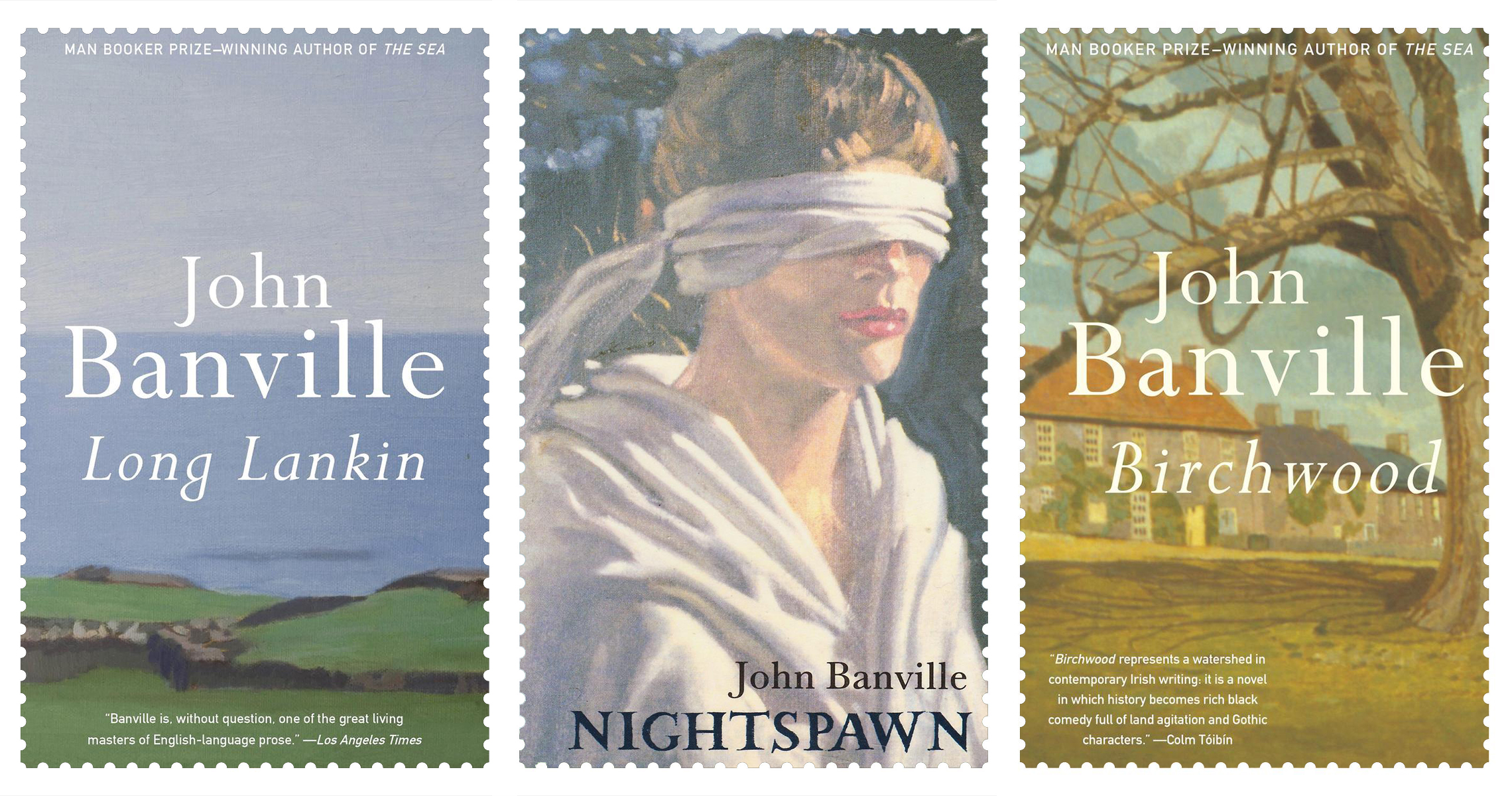

Settling in Dublin, Banville found work as a sub-editor — or copy editor, as the position is known in the United States — at The Irish Press, a daily newspaper. He continued to write all the while, and in 1970 his first book of stories, Long Lankin, was published. His first novel, Nightspawn, appeared in 1971, followed by a second novel, Birchwood, two years later. Many years would pass before Banville could depend on his writing for his livelihood, and he continued to work at The Irish Press while he and Janet raised their two sons.

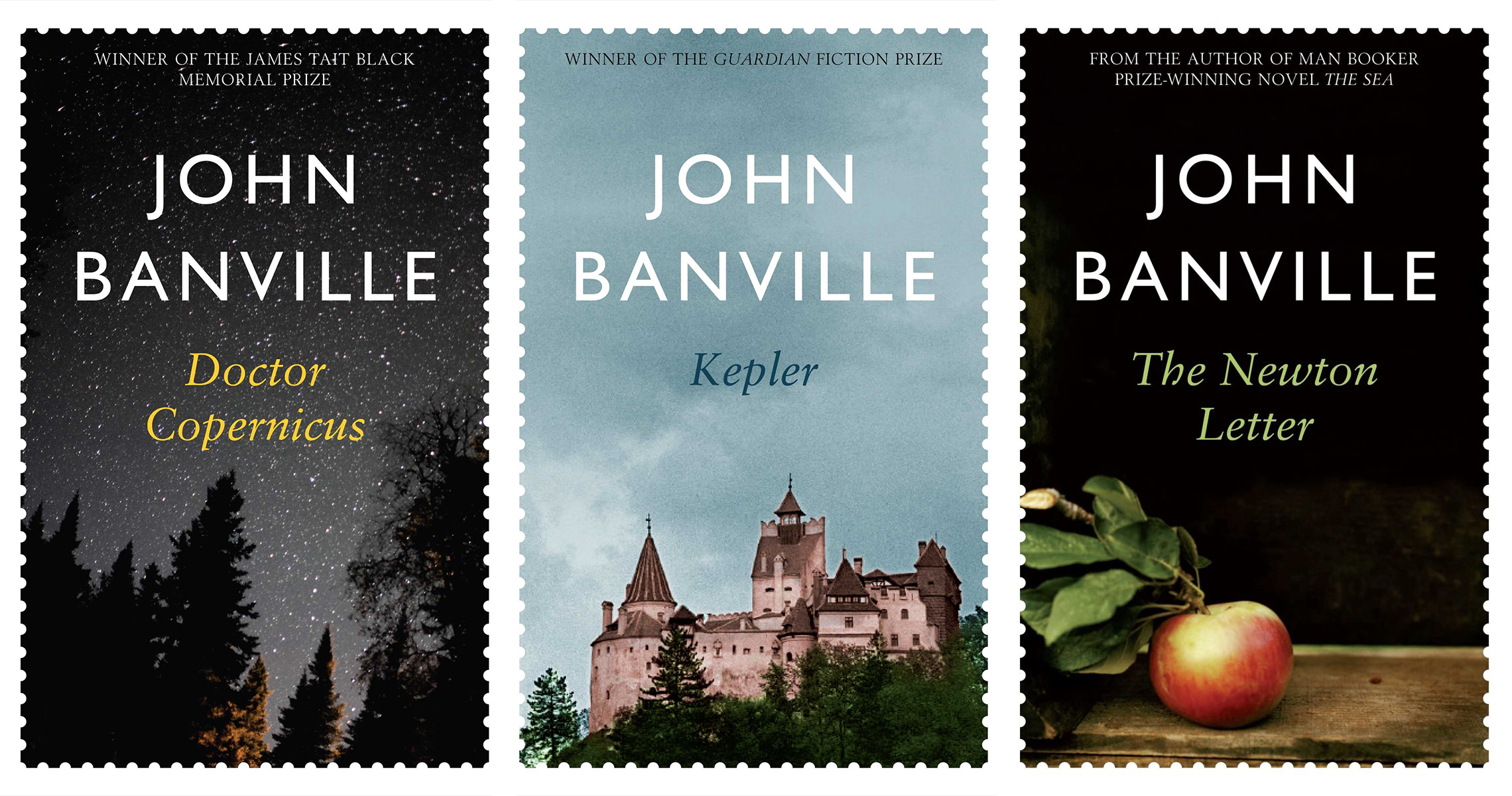

As Banville acquired mastery of his form, he undertook more and more ambitious projects. In a trilogy of novels — Doctor Copernicus (1976), Kepler (1981) and The Newton Letter (1982) — he explored the lives of pioneering scientists. The first of these brought Banville one of his first major literary awards, the James Tait Black Prize for Fiction. The Newton Letter was the first of Banville’s works to be adapted for film or television. Banville’s television adaptation, Reflections, was broadcast by the BBC in 1984. A standalone novel, Mefisto (1986), was followed by another trilogy. The Book of Evidence (1989), Ghosts (1993) and Athena (1995) feature an interlocking cast of characters and deal with questions of art, mythology, murder, and a disturbingly unreliable narrator.

The Book of Evidence drew its inspiration from an actual murder committed in Dublin some years previously and was shortlisted for Britain’s prestigious Booker Prize. Banville’s novels were attracting increasing attention from the literary press. The Irish Press, financially troubled for years, finally ceased publication in 1995, and Banville moved to The Irish Times, where he was appointed literary editor in 1998. He remained at the Times for many years and has continued to contribute reviews to the paper long after he ceased to depend on it for his income. His work was being read well outside of Ireland, and he began writing essays and criticism for international publications, including The New York Review of Books.

Banville continued to branch out in his writing, with another film for television and the first of a series of adaptations of plays by the 19th-century German author Heinrich von Kleist. He drew more praise for his 1997 novel, The Untouchable, which dealt with a fictional traitor, modeled in part on Sir Anthony Blunt, the British art historian and Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures, who was exposed publicly as a Soviet spy many years after his confession to the authorities.

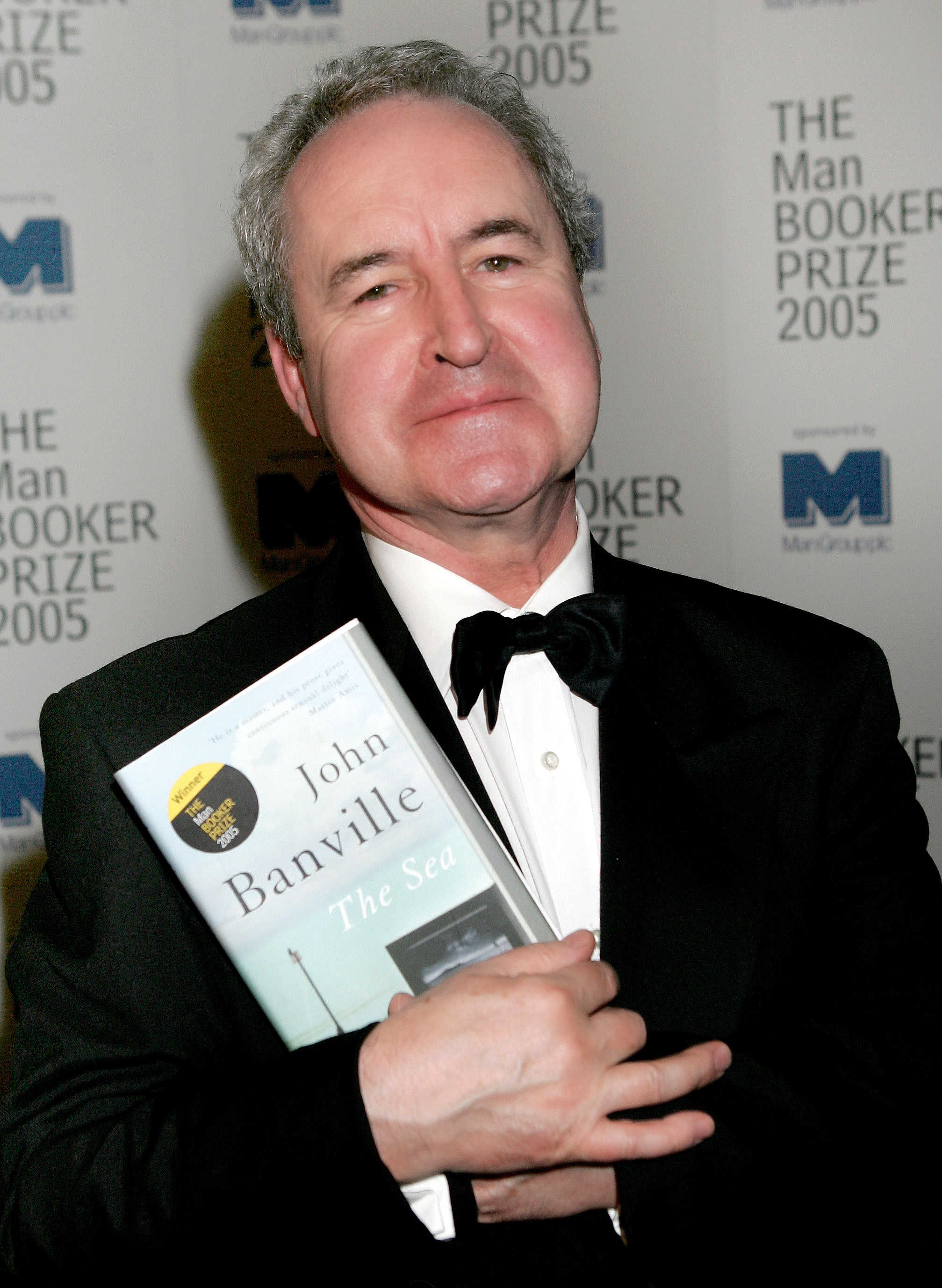

A third trilogy, also featuring a recurring set of characters, began to appear in 2000, with Eclipse, followed by Shroud (2002). The following years, Banville published a work of nonfiction, Prague Pictures: Portrait of a City. Banville continued his interest in the work of Heinrich von Kleist with God’s Gift (2000) and Love in the Wars (2005), theatrical adaptations of Kleist’s Amphitryon and Penthesilea, respectively. Banville’s novel The Sea (2005) is set, in part, in an Irish seaside village like one the author knew as a child. The Sea was acclaimed as Banville’s masterwork and at last brought him the Booker Prize, the most coveted award in English letters.

On the side, Banville concocted an alter ego, “Benjamin Black,” to write genre mystery novels as a vacation from his serious literary work. He writes his Benjamin Black stories more quickly than his other novels, usually over the summer, returning to his literary labors in the autumn. Half a dozen of the Black novels, beginning with Christine Falls in 2006, featured as their protagonist a Dublin pathologist called Dr. Quirke, but more recently, “Benjamin Black” has taken on historical subjects as well. In The Black-Eyed Blonde, Black continued the adventures of Philp Marlowe, the hard-boiled sleuth created by American crime writer Raymond Chandler in the 1930s.

Under his own name, John Banville continued a variety of literary activities, writing screenplays for films, including Albert Nobbs, from a story by the Irish writer George Moore; The End of the Affair, based on the novel by Graham Greene; and the film adaptation of his own novel The Sea. His subsequent novels have included The Infinities (2009), which revisited the myth of Amphitryon he had explored in God’s Gift; Ancient Light (2012), which concluded the trilogy begun with Eclipse and Shroud; and the 2015 novel The Blue Guitar. In 2016, Banville published a nonfiction travelogue and love letter to the city he has long called home, Time Pieces: A Dublin Memoir.

Banville’s work has enjoyed great success not only in the English-speaking world but in translation. He has received three major literary prizes — including a knighthood — in Italy alone, as well as honors in Austria, the Czech Republic (the Franz Kafka Prize) and Spain (the Prince of Asturias Award). He has been proposed repeatedly as a candidate for the Nobel Prize in Literature.

As a young writer, Banville had struggled to escape the overpowering influence of his compatriot James Joyce and found an alternative model in the work of another Irish author, Samuel Beckett, whose novels and plays often featured eccentric, obsessive narrators like those found in some of Banville’s works. Critics have compared Banville’s rapturous attention to the details of everyday life to the work of the French novelist Marcel Proust and the great Russian-American stylist Vladimir Nabokov. Although Banville has acknowledged his admiration for Nabokov as well as Franz Kafka, he has long claimed the American author Henry James as his most important influence. Banville repaid his debt to James with a tribute in the form of a novel, Mrs. Osmond (2017), continuing the story of Isabel Archer, the heroine of James’s Portrait of a Lady.

In 2020, Banville announced that he was abandoning his Benjamin Black pseudonym and merged his two authorial personae in Snow, a novel, set in Ireland in the 1950s, which fuses the conventions of the traditional “country house” mystery with the sophistication of Banville’s literary fiction. In 2025, Banville published Venetian Vespers, a historical crime novel set in 1899 Venice, narrated by Evelyn Dolman, a minor Englishman of letters whose vanity and unreliability deepen amid avarice, masquerade, and a disturbing disappearance, in a late-Victorian idiom that mirrors his pretensions.

Having already published more than 30 books, John Banville continues to write every day, keeping regular hours in an office he maintains near his home in Dublin. His marriage to Janet Dunham ended many years ago and their sons are grown. Since then, he has lived in Dublin with his partner, Patricia Quinn. They have two daughters.

(John Banville reads the opening paragraph of his Booker Prize novel, The Sea.)

“They departed, the gods, on the day of the strange tide. All morning under a milky sky the waters in the bay had swelled and swelled, rising to unheard-of heights, the small waves creeping over parched sand that for years had known no wetting save for rain and lapping the very bases of the dunes. The rusted hulk of the freighter that had run aground at the far end of the bay longer ago than any of us could remember must have thought it was being granted a relaunch. I would not swim again, after that day. The seabirds mewled and swooped, unnerved, it seemed, by the spectacle of that vast bowl of water bulging like a blister, lead-blue and malignantly agleam. They looked unnaturally white, that day, those birds. The waves were depositing a fringe of soiled yellow foam along the waterline. No sail marred the high horizon. I would not swim, no, not ever again. Someone has just walked over my grave. Someone.”

The Irish author John Banville has been praised as the most imaginative literary novelist writing in English today, as well as one of the language’s greatest living stylists. In addition to his perfectly crafted, lyrical prose, his novels are noted for the mordant humor of his eccentric narrators.

John Banville wrote his first book of short stories at 25 and to date has published 18 novels under his own name, including the Revolutions trilogy examining the lives of Copernicus, Kepler, and Newton. As a break from his literary fiction, he has written a series of crime novels under the pen name Benjamin Black.

After numerous nominations for his earlier work, Banville was awarded the English-speaking world’s highest literary honor, the Man Booker Prize, for his 2005 novel of childhood and memory, The Sea. A dramatist and screenwriter as well as a novelist, he has adapted three plays by the German dramatist Heinrich von Kleist, and written screenplays for films, including an adaptation of his novel The Sea. He has also developed a television series, Quirke, based on the pathologist hero of his popular mysteries.

Most writers have a regular routine. How about you? Do you have a daily routine?

John Banville: I keep office hours. I work from 9:30 to 6:00. It’s curious. In the morning, I could just about tie my shoelaces before noon, but I can write. It’s obviously a different part of my brain that’s working.

Is your favorite time to write in the morning?

John Banville: No. The afternoon.

Morning, you write for maybe three hours, but you’re still just preparing. But about 3:00 in the afternoon, when I’ve sunk to such a level of concentration that I don’t know who I am, time expands and contracts. I was working one day in my study and my wife put her head in the door and said, “I’m going to the shops.” She closed the door and then opened it again. I said, “I thought you were going to the shops.” She said, “I have been to the shops.” But I had no sense of that time having passed. I was in a different temporal area. And that’s where you really concentrate. You forget yourself. You forget your surroundings. You forget everything.

What are you concentrating on? The characters? The movement of the story?

John Banville: Oh no, the language. The language. Everything comes out of the language — the plot, character, everything. And it’s the sentence. The sentence is how I work, that’s the unit that I work by. James Joyce worked by the paragraph. Very few people ever notice that, but Joyce is a master of the paragraph. I’m not very good at paragraphs, but I’m not too bad at sentences. And each sentence generates the next one. If you get a sentence that’s as close to being perfect as you can — which is still pretty far away from perfect, but it’s as close as you can get — then that generates the next one. And I trust the sentence to create characters, to make a plot, to carry me along. Anyway, what’s the point of a plot, you know? Has life got a plot? Not that I know of. So why should a novel have a plot? But it has to have some kind of story. It has to have some kind of structure.

When reviewers write about your work, they often mention the sense of place, that the settings really come alive in your work. Is that what you work for?

John Banville: I try to have a sense of immediacy. It seems to me that the only reason to make a work of art is to try to make the reader or the listener or the viewer feel, taste, hear, smell the world as it is. But of course, we don’t do it as it is. A novel is nothing like the world and nothing like life, but it produces a wonderful simulacrum of it. A strangely compelling parallel version of the world that people think is real. I wrote a book once about Johannes Kepler, the great astronomer who lived in the 1600s. And people said to me how well I’d caught the period. But I was too polite to say to them, “How do you know?” But they were giving me a wonderful compliment. They were saying, “You created something here that looks and sounds and smells to me what I imagine the 1600s were like.” So that’s all we can do is — it’s a kind of glorified transcendental lying. That’s what fiction is.

And why do you love that?

John Banville: I love telling lies. I love making stories. I love interpreting the world. It’s why I started to write, in order to interpret the world to myself because I didn’t understand it. I found it baffling. I find the world baffling. I think the only reason that we’re not constantly surprised is that, as Beckett says, “Habit is a great deadener.” But the sky is an extraordinary phenomenon. You look up and you’re looking into infinity. And then the clouds come along. Clouds are the most amazing things. The sea is amazing. It’s flat. Everything else in the world is up and down. The sea is flat. And you walk along the land, and you come to this extraordinary flat phenomenon. It never ceases to baffle me.

How do you begin work on a book?

John Banville: I think it begins as a kind of tension in space. There’s something out there and it’s waiting for the big bang, and I have to get that into my head. I have a composer friend in Ireland, and he beautifully said, “I have this scream in my head and I have to get it into the orchestra. I have to get it into the music.” But I wouldn’t be quite as dramatic as that. But I have this tension. I have this thing that has to be done. And the problem is, you see, once you’ve got the first paragraph down and you’ve got the tone, then the bloody book is written. All you have to do is fill it in then, which makes it really boring. I mean I’d like to be like one of those Japanese artists, you know, just go shoop! and it’s done. But no, it takes years.

When you write that first paragraph and you have the tone right, do you know where it’s going to go, or does it keep unfolding?

John Banville: The first paragraph is the absolute. For me, it’s the essential. One of my books — I can’t remember which — I spent, I think, three, maybe four, months writing the first paragraph. Sometimes I was just writing the same paragraph, trying to get the tone, because tone is everything. Now don’t ask me to explain what tone is. But I have to hear the voice. And every novel has its own voice and its own tone. Once you get that, then you’ve got it. And curiously, it has a lot to do with getting the names of the characters right. If you’re going through Henry James’s notebooks, you see a long list of names, possible names. Now, how do you know when a character’s name is right? You don’t. But somehow it makes a chime. It just sounds — it feels right, and that is very important for me.

Do you read your paragraph over and over again so that you can hear the chime?

John Banville: I have this very rich, poetic voice that I hear myself reading in. I do it with this sort of cadence — vroom! — chanting it. I’m not aware I’m doing it. That’s for the rhythm. I mean rhythm is almost as important as tone. I’ve been planning — for the past week, I’ve been planning, writing and rewriting the first sentence of my next book over and over again. I sent my wife three separate versions of it by email last night, asking her which sounds best. And I’ll be doing that for weeks and weeks and weeks. But when I get that sentence right, then I’ll know that I can get going on the first paragraph. And when I get the first paragraph as near to right as I can get it, then I’ll be on my way. I just ask her opinion. She has perfect pitch as far as my work is concerned. One of my books, I remember, she took me away for a weekend after I had given it to her to read, and she said, “You can’t do this, you know. You can’t publish this. You’ll disgrace yourself.” I started blustering, and she said, “Bluster away, but you know yourself it’s not right.” And of course it wasn’t, and I had to go back through it, like clawing sort of grass out of a pond, getting rid of the awful stuff that was there to leave the clear water behind.

You once said that you have to try to do things that you think you’re incapable of. What did you mean?

John Banville: You have to do what’s difficult. You have to push yourself beyond what you know you can do. Otherwise it would be so boring.

Writing is such a solitary endeavor. Is it hard work for you?

John Banville: It’s immensely hard work, but what’s the point of doing easy work? It’s immensely rewarding. It’s immensely infuriating and painful and horrifying at times. I remember when I was doing one of my books and it was giving me a sense of trouble. I sat down in a chair one day. I couldn’t do any more. I actually had a vision of myself writhing in pain on the floor. So it’s terribly, terribly difficult. But you know, anything worthwhile doing is always difficult.

When you do take a break from writing, what do you do?

John Banville: I never do. I write 24 hours a day, even when I’m asleep. Especially when I’m asleep! I mean we all write when we’re asleep. As Nietzsche said, every man’s an artist when he sleeps. They make up these fantastic worlds, people you’ve never met, places you’ve never been to, things you’ve never done. And for the period that you’re dreaming of it, they’re absolutely real. Extraordinary phenomenon!

But you’ve had massive success. You’ve won all these prizes. Can’t you just take it easy now?

John Banville: I’d melt! And now I’ve come to an age where I keep waiting for the day when I forget a word and have forgotten it in such a way that I know it’s gone and then I know dementia is coming on. Maybe then I’ll give up. I might go back to painting then. I might discover that I wasn’t too bad after all. But there’s a wonderful story of Henry James when he was dying. He was in a coma and his hand was moving across the sheet. He was still writing. That will be me, writing until I fall off the edge.