The building of the architecture of a novel — the craft of it — is something I never tire of.

John Irving was born John Wallace Blunt, Jr. in Exeter, New Hampshire during World War II. At the time of his birth, his father was serving as an airman in the Pacific. His parents divorced when he was only two years old. He was renamed John Winslow Irving when his mother re-married in 1948, and he grew up without ever meeting his biological father.

As a boy, John Irving was notably withdrawn, a characteristic he attributes not to unhappiness but to an inborn love of solitude that he believes has served him well as a writer. He read with difficulty, a learning disorder that today would probably be characterized as dyslexia. In spite of this, he became an enthusiastic reader and student of literature. As a student at the Philips Exeter Academy, where his stepfather taught Russian history, John Irving began to wrestle competitively, a sport he credits with teaching him discipline and perseverance.

Irving left the University of Pittsburgh after one year and moved to Vienna, Austria. He studied at the University of Vienna and roamed Europe on a motorcycle, absorbing many of the experiences that would later find their way into his novels. After returning to the United States, he enrolled in the University of New Hampshire, and graduated in 1965. He married while still an undergraduate, and became a father at 23. Already set on a writing career, he earned a master of fine arts degree from the creative writing program at the University of Iowa, where his instructors included Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.

After completing his graduate degree in 1967, Irving returned to New England with his growing family, and took a job as Assistant Professor of English at Windham College in Vermont. His first novel, Setting Free the Bears, published when he was 26, drew on his European experiences for a darkly comic story of two students who conspire to liberate the animals from the Vienna zoo. Inspired by an actual incident from the last days of World War II, it introduced many of the themes and techniques he has explored throughout his career: the disasters of history and the capriciousness of fate, dramatized through interlocking stories within stories. He was approached to adapt his novel for the screen, in collaboration with director Irving Kershner. Although nothing came of the project, it was not to be John Irving’s last encounter with Hollywood. In the meanwhile, his academic earnings were augmented by a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation.

Irving’s second novel, The Water-Method Man, published in 1972, revisited the Austrian locale of Setting Free the Bears, while also satirizing academic life in America. That same year, Irving was appointed Writer-in-Residence at the University of Iowa. Irving’s 1974 novel, The 158-Pound Marriage, was more narrowly focused than his previous efforts, concentrating on the erotic intrigues of two couples in an American university setting. Its title plays on a term from the world of wrestling, a sport in which Irving continued to compete as an adult. While at the University of Iowa, Irving received a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. In 1975, Irving took a job as Assistant Professor of English at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts. The move back to New England was a welcome one; he has kept a home in the region ever since. While teaching at Mount Holyoke, Irving received additional support from the Guggenheim Foundation, and served as Writer-in-Residence at the Bread Loaf Writers Conference. Although Irving’s first three novels were well-received critically, popular success had eluded him for a decade. The publication of his fourth novel was to change his life irrevocably. The World According to Garp featured, as its protagonist, an author whose stories comment on his own life and on the book itself, and involve him with a set of dizzyingly eccentric characters, besieged by hostile fate. First published in 1978, Garp received ecstatic reviews and sold prodigiously. It won its author a loyal worldwide audience. Passed over for the National Book Award in 1979, it was honored in 1980 when the National Book Foundation granted separate awards for fiction in hardcover and paperback. Since the international success of Garp, every book Irving has written has been a bestseller. Although success freed Irving to write full-time, he did not choose to cloister himself in his study. After completing the last of his Writer-in-Residence appointments, this one at Brandeis University, he coached wrestling at prep schools for most of the 1980s, while writing the most popular literary novels of the decade.

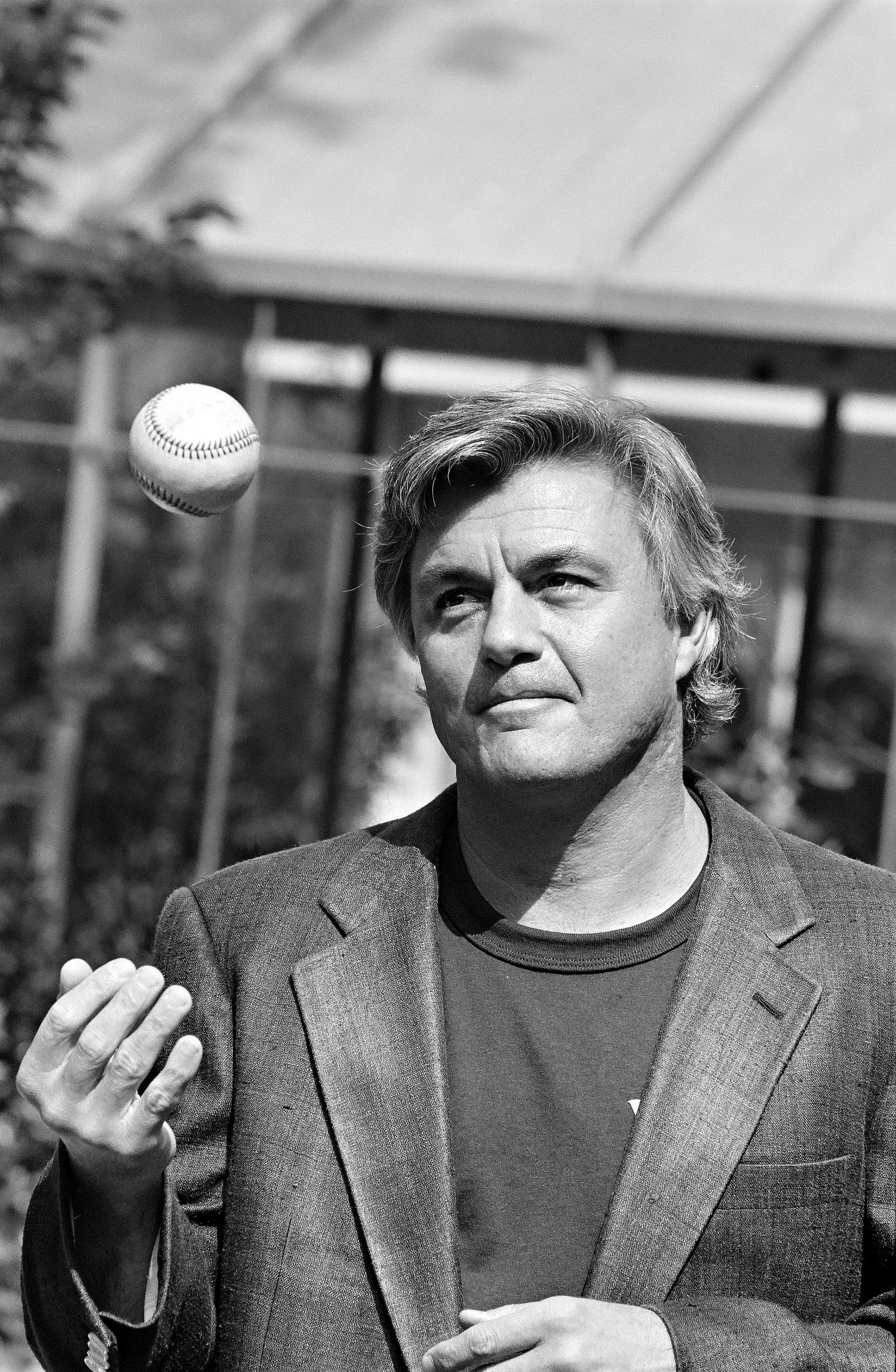

Like The World According to Garp, Irving’s next novel, The Hotel New Hampshire (1981), presented a cast of vividly imagined eccentric characters. The Cider House Rules (1985) is set in Maine in the early decades of the 20th century, at an orphanage presided over by a kindly, ether-addicted obstetrician and abortionist. This book threw Irving into the thick of the debate over abortion in America. Irving’s own pro-choice position was informed in part by the life and writings of his adoptive grandfather, a prominent obstetrician and gynecologist. Questions of religion, morality and the randomness of fate figure strongly in Irving’s next work, A Prayer for Owen Meany (1989), in which a foul ball hit by a small boy in a Little League game kills a spectator, the mother of the boy’s teammate.

The World According to Garp was made into a successful film, released in 1982. A film adaptation of The Hotel New Hampshire followed quickly. A Prayer for Owen Meany was filmed under the title Simon Birch in 1998. Filming The Cider House Rules proved to be a more challenging undertaking. In his book My Movie Business, Irving recounts that it took “two producers, four directors, 13 years, and uncounted rewrites” to bring the book to the screen. It was worth the wait. The film, finally directed by Lasse Hallstrom, was both a critical and a popular success. Irving wrote the screenplay himself, and received the 2000 Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay. Irving’s novel A Widow for One Year (1998) was the next of his works to be adapted. In 2004, a film version was released, entitled A Door in the Floor.

In the 1990s, Irving’s work became increasingly dark and complex, and the intricacy of his plots drew frequent comparison to the work of Charles Dickens. A Son of the Circus (1994) introduces us to an East Indian doctor, now living in Canada, and immerses us in his memories of childhood in a traveling circus in rural India, a surreal dream world of freaks and wonder-workers. In The Fourth Hand (2001), also set partly in India, a photojournalist loses his hand in an accident and receives the world’s first hand transplant. Complications ensue when the widow of the hand’s donor insists on visitation rights with her deceased husband’s hand. In Until I Find You (2004), a successful actor recalls a childhood spent searching for his church organist father in the tattoo parlors of Northern Europe. During the writing of this book, Irving was contacted for the first time by a half-brother he had never met, and at last learned something of the life and character of the father he never knew. His 2009 novel, Last Night in Twisted River, set in the logging country of northern New Hampshire, also treats the complex relations of fathers and sons.

Apart from his novels, Irving has published a collection of short stories, Trying to Save Piggy Sneed, including a “miniature autobiography,” The Imaginary Girlfriend, embodying his reflections on writing and wrestling. Throughout his work, he has expressed a warm affection for humanity in all its astounding variety, and a deep admiration for the courage and good humor of men, women and children in confronting the cruelties and catastrophes of life. Among other subjects, he has displayed a continuing interest in themes of marriage and family life. Although his own first marriage ended in 1981, he married his literary agent, Janet Turnbull, in 1987 and began a second family.

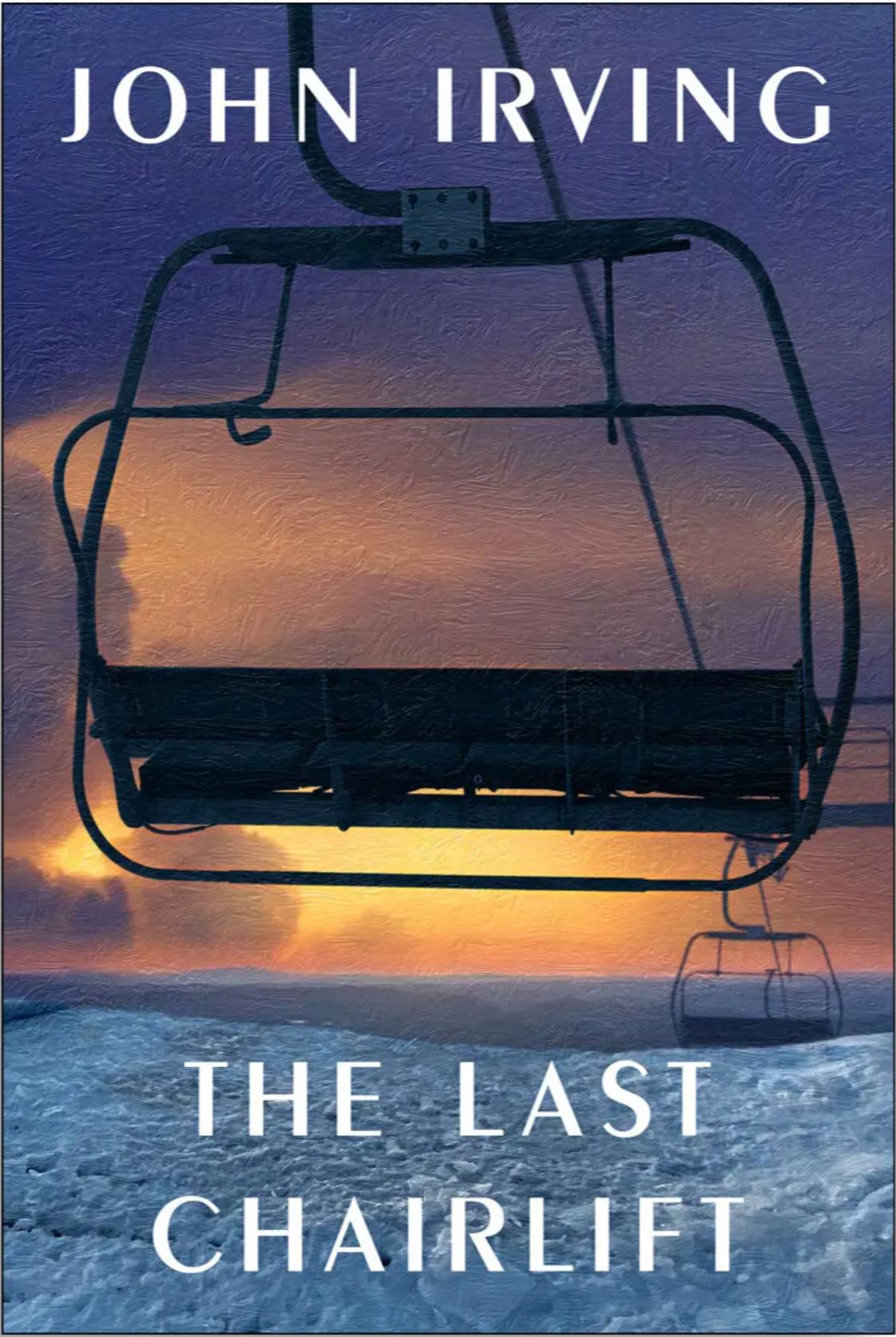

In October 2022, Irving, who turned 80 earlier this year, released his 15th novel, The Last Chairlift—a ghost story, a love story, and a lifetime of sexual politics. Today, John Irving and his family live in Vermont and in Toronto. He continues to write novels and to adapt his previous works for motion pictures. Around the world, readers eagerly await his next book, but his past works have long since established him as a master storyteller and comic genius of our age.

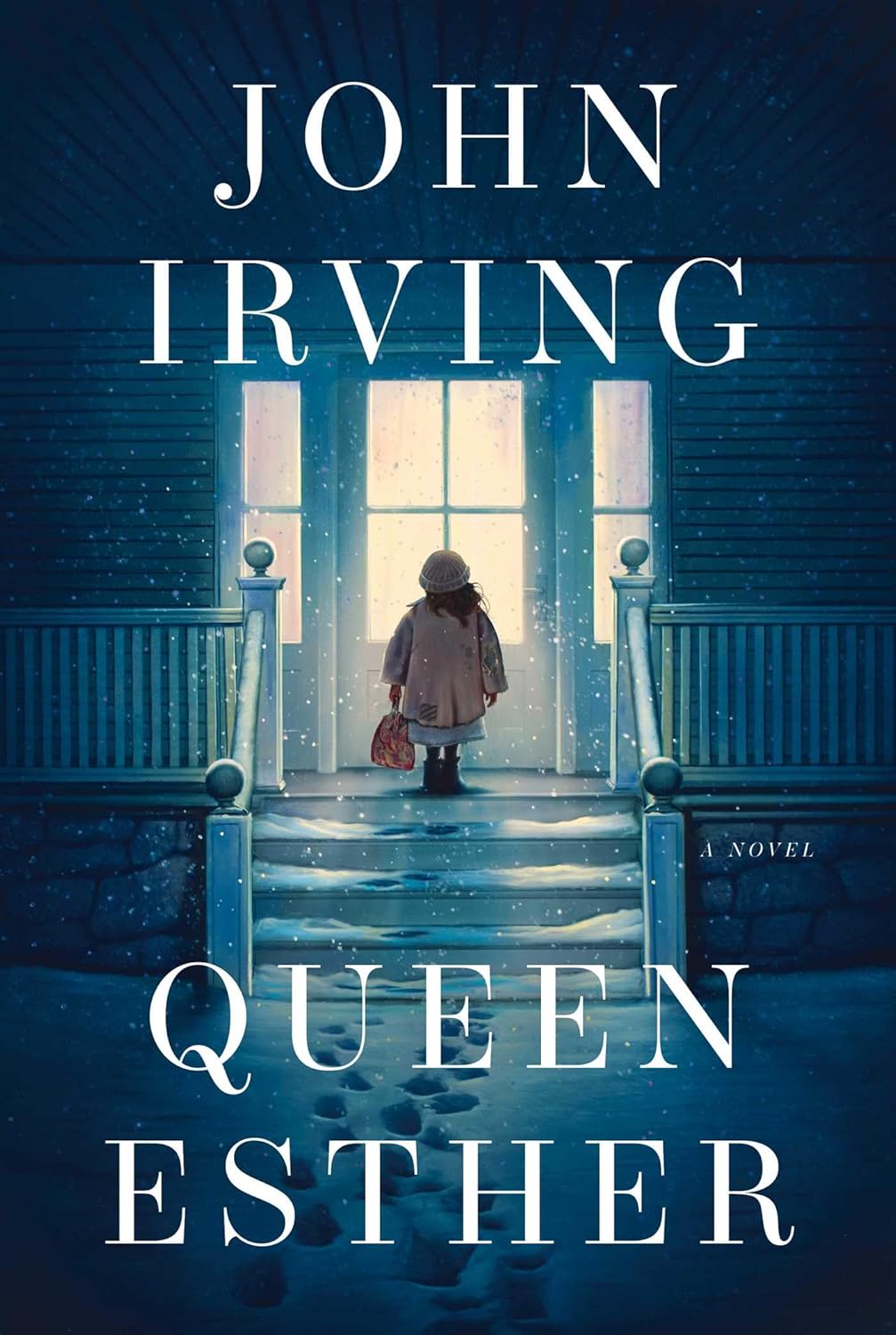

In November 2025, Irving published his sixteenth novel, Queen Esther, returning to the world of The Cider House Rules and to the orphanage at St. Cloud’s in Maine. The story follows Esther Nacht, a Jewish orphan whose life is shaped by displacement, resilience, and the persistence of prejudice. Raised first by Dr. Wilbur Larch and later by the Winslow family of New England, Esther’s story spans from Maine to Vienna and, ultimately, to Jerusalem. In its focus on identity, chosen family, and the burden of history, Queen Esther continues Irving’s long engagement with how larger forces shape personal lives.

Readers around the world have embraced the vivid characters who tumble through the intricately imagined tales of John Irving. He published his first novel when he was 26, and won the National Book Award for The World According to Garp in 1980. Since then, every one of his novels has been an international bestseller, including The Hotel New Hampshire, The Cider House Rules and A Prayer for Owen Meany.

As a boy, John Irving struggled with dyslexia. While other young people with this obstacle might have turned away from books and reading, the necessity of struggling over every word had the opposite effect on Irving; it taught him a deep respect for the power of language. After graduating from the master of fine arts creative writing program at the University of Iowa, where he studied with Kurt Vonnegut, Irving taught English and writing at Windham College and Mt. Holyoke.

For years, Irving balanced his imaginative undertakings with a grueling physical discipline. He wrestled competitively for 20 years, and continued to coach the sport in prep schools long after achieving success as a writer. In 1992, he was inducted into the National Wrestling Hall of Fame. He plays an active role in the adaptation of his books to the screen, winning an Oscar for the screenplay of The Cider House Rules.

What was your childhood like, growing up in Exeter, New Hampshire?

John Irving: It was reasonably secluded, largely happy, but there was a mystery in it that I think provoked my imagination.

No adult in my family would ever tell me anything about who my father was. I knew from an older cousin — only four years older than I am — everything, or what little I could discover about him. I mistakenly thought that he and my mother were married and divorced before I was born. As it turned out, I was born in 1942, and my parents didn’t divorce until 1944, when I was two. But I was born with that father’s name, John Wallace Blunt, Jr., and it probably was a gift to my imagination that my mother wouldn’t talk about him, because when information of that kind is denied to you as a child, you begin to invent who your father might have been, and this becomes a secret, a private obsession, which I would say is an apt description of writing novels and screenplays, of making things up in lieu of knowing the real answer.

I was 39 and divorcing my first wife when my mother deposited on my dining room table some letters from my father which were written from an air base in India and from hospitals in India and China in 1943. He was a flyer, he flew the Himalayan route, as it was called. He and his crew were shot down over Japanese-occupied Burma and hiked for 15 days, some 225 miles into China. The letters were all patiently, painstakingly explaining to her why he didn’t want to remain married to her, but that he hoped to have some contact with me. My mom never permitted him that contact.

In 1948, when I was six, she remarried, and my stepfather, Colin Irving, legally adopted me, so that my name was changed from John Wallace Blunt, Jr., to John Winslow Irving, Winslow being my mom’s maiden name. And the mystery continued.

I think it probably is the most central or informative part of my childhood, is what I didn’t know about it. And as friends and critics have been saying of my novels for some time, I’ve been inventing that missing parent, that absent father, in one novel after another. It was both a surprise, but an easing of a burden when, in the middle of the novel I just finished — which I began in 1998 and finished only this spring — in 2002, in December of 2002, in the middle of that book, which was, once again, a “missing father” novel, I was contacted by a 39-year-old man named Chris Blunt, who said, “There’s a possible chance that I might be your brother.” And of course, I knew it was not a possible chance at all, but a likelihood. And I since have met two brothers and a sister I didn’t know about, and I found out more about this man who died five years before Chris found me. And the coincidences of the father I was imagining — who was waiting for me to finish my story in the last two chapters of this novel — the actual father turned out to have some similarities to the man I had already imagined.

Not as surprising as you might think, given the fact that when you’re a kid and you don’t know about someone, it’s natural to demonize him. In other words, if no one would talk about this guy, how bad a guy was he? There must have been something wrong with him or people would have talked to me. At least that’s always the way my imagination runs. Imagine the worst, right? Imagine the worst.

Well, it was nice to hear from these two brothers and my one sister that they loved him, that they thought he was a good father, although he was married four times and had children with three of those wives, not the fourth. It was astonishing for the first time to see, in my late 50’s, early 60’s, which I was at the time, photographs of my father when he’s younger than my grown children are today. I have a 40-year-old son and a 36-year-old son, and I’m looking at pictures of Lieutenant John Wallace Blunt when he’s 24, with his flight crew in China. And he doesn’t look like me, to my eyes, although he does. What he really looks like is one of my kids. He so much more closely resembles them than he does me.

Aside from stimulating your imagination, did this impact your childhood in other ways? Were you a good kid?

John Irving: I was a moody kid. I was an aloof kid, I kind of kept to myself. I think that an early sort of pre-writing indication that I had the calling to be a writer was how much time I liked to spend alone. I wasn’t anti-social. I had friends, but I didn’t really want to hang out with them after school. What I saw of them at school was enough. I needed to be in a room by myself even before I was writing, just imagining things, just thinking about things. If there was a weekend with too many cousins or other people around, I got a little edgy. I think the need to be by myself, which I’ve recognized in a couple of my own children, is one that was respected by my grandmother, with whom I lived until my mom remarried, as I told you, when I was six. And I was fortunate to be in a big house, my grandmother’s house, and there were lots of places to get off by yourself and imagine those things that I didn’t know. And I find — I’m 63, and my capacity to be by myself and just spend time by myself hasn’t diminished any. That’s the necessary part of being a writer, you better like being alone.

When did you know that you wanted to be a writer, a novelist?

John Irving: Well, before I went to college anyway.

When I was still in prep school —14, 15 — I started keeping notebooks, journals. I started writing, almost like landscape drawing or life drawing. I never kept a diary, I never wrote about my day and what happened to me, but I described things. If I had known how to draw, maybe I would have drawn hundreds of pictures of my grandmother’s garden, but instead I wrote sort of landscape descriptions of it. I think that was what was so compelling to me about those Dickens and Hardy novels. Just the lushness of detail, the amount of description, the amount of atmosphere that is plumped into those novels. It’s like nothing you read today, except from those writers who are essentially 19th century storytellers themselves: the Canadian, Robertson Davies; the German, Günter Grass; Garcia Marquez; Salman Rushdie. Basically old fashioned 19th century plot-driven storytellers. Among my contemporaries, I still like the old fashioned ones. Some exceptions, to be sure. I mean Graham Greene is such a good storyteller that I forgive him for being as modern as he is. But I was never a Hemingway person. I never understood that. Moby Dick, there was a story. The longer, the better. I remember kids who were reading Moby Dick in a class and would be just complaining about, “Do we have to know everything about the whaling industry? Do we have to read about the blubber and all the rest of it?” I couldn’t get enough of it, you know. I couldn’t get enough of it.

For someone who doesn’t understand what a writer does, or how it happens, how would you explain what you do and how you do it?

John Irving: Well, I’ve always been patient.

I don’t begin a novel or a screenplay until I know the ending. And I don’t mean only that I have to know what happens. I mean that I have to hear the actual sentences. I have to know what atmosphere the words convey. Or is it a melancholic story? Is there something uplifting or not about it? Is it soulful? Is it mournful? Is it exuberant? What is the language that describes the end of the story? And I don’t want to begin something, I don’t want to write that first sentence until all the important connections in the novel are known to me. As if the story has already taken place, and it’s my responsibility to put it in the right order to tell it to you. Do I begin at the beginning chronologically? Sometimes. Or is it the kind of story that’s better to jump into in the middle and go backwards and forwards at the same time? I am a person who just can’t make those judgments — I can’t come to those decisions — unless I know what’s waiting for me at the end. What makes this story worth the five years it’s going to take me to write it? What is emotionally compelling enough at the end of this novel? What’s waiting for you that’s going to move you at the end of this story? That makes a reader tolerate how long and complicated and at times difficult it’s going to be? And so I always go there. I write those end notes as if they were two pieces of music, so I know what I’m going to hear at the end of the story. I know what the sentences themselves, what they’re going to sound like, and I put them in a log. You know? And they’re waiting for me, and I know I’m not going to get to that part of the story for four, five — in the case of this most recent novel, seven years, but it’s important to me that I hear it.

In The World According to Garp, “We are all terminal cases” was the first sentence I wrote, the last sentence of the book. “Oh God, please give him back, I shall keep asking you,” in a A Prayer for Owen Meany, was the first sentence I wrote. The whole novel is a prayer, but what’s the prayer at the end? What is the narrative? Why he wants him back. I have to know those things.

I think working my way through that process, begin with the end and then work your way back to where you began. Sometimes that’s a year, sometimes it’s 18 months, where all I’m doing is taking notes. I’m reconstructing the story from the back to the front so that I know where the front is. Now people always ask me, “Well surely something changes. Surely somewhere along the way you get a better idea.” In the sequence of events in the middle of the story, that’s often true. Sometimes a character I had never thought of — a minor character or a major/minor one— will make an appearance in the middle of the story and move the story in a slightly different way. But the ending never changes. It never has. Eleven novels, it never has changed. I might fool around with that first sentence over time, but I won’t fool around with the last. It’s as clear as a note of music. It is where I’m going.