My mother used to have dreams about being a writer and I used to watch her.

John Updike was born in Reading, Pennsylvania, and spent his first years in nearby Shillington, a small town where his father was a high school science teacher. The area surrounding Reading has provided the setting for many of his stories, with the invented towns of Brewer and Olinger standing in for Reading and Shillington. An only child, Updike and his parents shared a house with his grandparents for much of his childhood. When he was 13, the family moved to his mother’s birthplace, a stone farmhouse on an 80-acre farm near Plowville, 11 miles from Shillington, where he continued to attend school.

At home, he consumed popular fiction, especially humor and mysteries. His mother, herself an aspiring writer, encouraged him to write and draw. He excelled in school and served as president and co-valedictorian of his graduating class at Shillington High School. For the first three summers after high school, he worked as a copy boy at the Reading Eagle newspaper, eventually producing a number of feature stories for the paper. He received a tuition scholarship to Harvard University, where he majored in English. As an undergraduate, he wrote stories and drew cartoons for the Harvard Lampoon humor magazine, serving as the magazine’s president in his senior year. Before graduating, he married fellow student Mary E. Pennington. He graduated summa cum laude from Harvard in 1954, and in that same year sold a poem and a short story to The New Yorker magazine.

Updike and his wife spent the following year in England, where Updike studied at Oxford’s Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art. While they were in England, their first daughter was born and Updike met the American writers E. B. and Katharine White, editors at The New Yorker, who urged him to seek a job at the magazine. On returning from England, the Updikes settled in Manhattan, where John took a position as a staff writer at The New Yorker. He worked at the magazine for nearly two years, writing editorials, features and reviews, but after the birth of a son in 1957, he decided to move his growing family to the small town of Ipswich, Massachusetts. He continued to contribute to The New Yorker but resolved to support his family by writing full-time, without taking a salaried position. He maintained a lifelong relationship with The New Yorker, where many of his poems, reviews and short stories appeared, but he resided in Massachusetts for the rest of his life.

Updike’s first book of poetry, The Carpentered Hen and Other Tame Creatures, was published by Harper and Brothers in 1958. When the publisher sought changes to the ending of his first novel, The Poorhouse Fair, he moved to Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. The first novel was well-received, and with support from the Guggenheim Fellowship, Updike undertook a more ambitious novel, Rabbit, Run. The novel introduced one of Updike’s most memorable characters, the small-town athlete, Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom. Knopf feared that his frank description of Rabbit’s sexual adventures could lead to prosecution for obscenity, and made a number of changes to the text. The book was published to widespread acclaim without legal repercussions. The original text was restored for the British edition a few years later, and subsequent American editions of the book have reflected the author’s original intent. Updike’s reputation as a leading author of his generation was established.

After the birth of a third child, Updike rented a one-room office above a restaurant in Ipswich, where he wrote for several hours every morning, six days a week, a schedule he adhered to throughout his career. In 1963, he received the National Book Award for his novel The Centaur, inspired by his childhood in Pennsylvania. The following year, at age 32, he became the youngest person ever elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters, and was invited by the State Department to tour eastern Europe as part of a cultural exchange program between the United States and the Soviet Union. In 1967, he joined the author Robert Penn Warren and other American writers in signing a letter urging Soviet writers to defend Jewish cultural institutions under attack by the Soviet government.

In 1968, Updike’s novel Couples created a national sensation with its portrayal of the complicated relationships among a set of young married couples in the suburbs. It remained on the bestseller lists for over a year and prompted a Time magazine cover story featuring Updike. In Bech: A Book (1970), Updike introduced a new protagonist, the imaginary novelist Henry Bech, who, like Rabbit Angstrom, was destined to reappear in Updike’s fiction for many years. Rabbit Angstrom reappeared in Rabbit Redux (1971).

In the 1970s, Updike continued to travel as a cultural ambassador of the United States, and in 1974 he joined authors John Cheever, Arthur Miller and Richard Wilbur in calling on the Soviet government to cease its persecution of dissident author Alexander Solzhenitsyn. Updike separated from his wife Mary in 1974 and moved to Boston, where he taught briefly at Boston University. Two years later, the Updikes were divorced, and in 1977 he married Martha Ruggles Bernhard, settling with her and her three children in Georgetown, Massachusetts.

Rabbit Is Rich, published in 1981, received numerous awards, including the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. In 1983 Updike’s other alter ego, Harry Bech, reappeared in Bech Is Back, and Updike was featured in a second Time magazine cover story, “Going Great at 50.” Among his novels of the 1980s and 1990s are a trilogy retelling The Scarlet Letter from the points of view of three different characters, and a prequel to Hamlet, entitled Gertrude and Claudius. In 1991 he received a second Pulitzer Prize for Rabbit at Rest. He was only the third American to win a second Pulitzer Prize in the fiction category.

In an autobiographical essay, Updike famously identified sex, art, and religion as “the three great secret things” in human experience. The grandson of a Presbyterian minister (his first father-in-law was also a minister), his writing in all genres has displayed a preoccupation with philosophical questions. A lifelong churchgoer and student of Christian theology, the Jesuit magazine America awarded him its Campion Award in 1997 as a “distinguished Christian person of letters.” He received the National Medal of Art from President George H.W. Bush in 1989, and in 2003 was presented with the National Medal for the Humanities from President George W. Bush. He was one of a very few Americans to receive both of these honors. The same year saw the publication of a comprehensive collection, The Early Stories, 1953-1975.

John Updike spent his last years in Beverly Farms, Massachusetts, in the same corner of New England where so much of his fiction is set. His last book was The Widows of Eastwick (2008), a sequel to his 1984 novel, The Witches of Eastwick. Updike succumbed to lung cancer in 2009 at the age of 76.

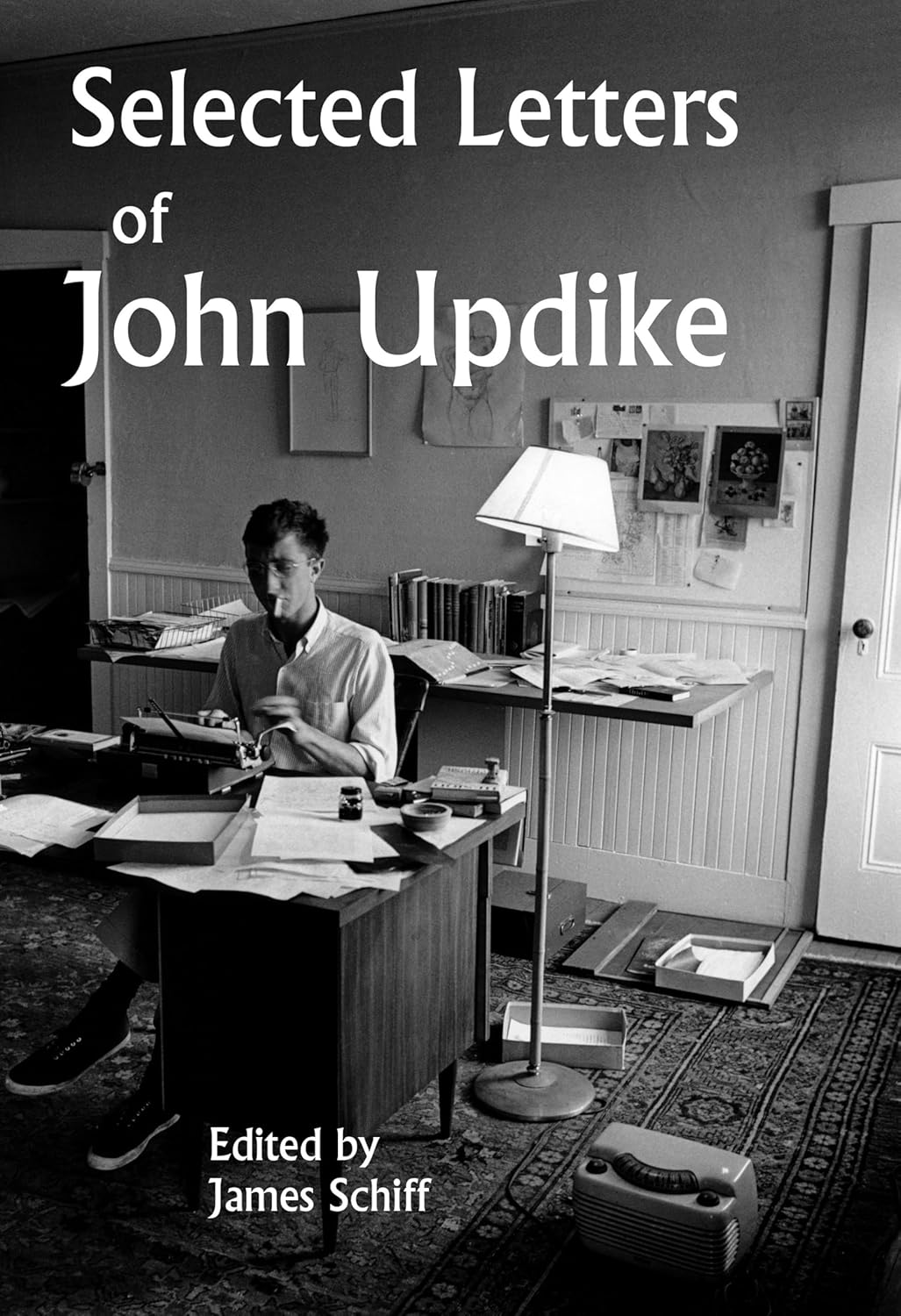

In October 2025, Selected Letters of John Updike, edited by James Schiff, was published. Spanning more than sixty years, the letters follow Updike from his Pennsylvania childhood and student years at Harvard through his career with The New Yorker and his life in Massachusetts. Addressed to family members, editors, fellow writers, friends, and lovers, they display the same clarity of observation and stylistic precision found in his fiction and essays. The letters record his early ambitions, the course of his marriages, his reflections on art and faith, and his exchanges with other figures in American literature. Taken together, they reveal the daily practice of a writer devoted to the written word.

“My mother had dreams of being a writer and I used to see her type in the front room. The front room is also where I would go when I was sick so I would sit there and watch her.”

Novelist, short story writer and poet, John Updike was one of America’s premier men of letters. As a boy growing up on a farm in Pennsylvania, he suffered from psoriasis and a stammer, ailments that set him apart from his peers. He found solace in writing, and won a scholarship to Harvard, where he edited the Lampoon humor magazine. He sold his first poem and short story to The New Yorker shortly after graduation.

He won early fame with his novel Rabbit, Run (1960), and Pulitzer Prizes for two of its sequels, Rabbit Is Rich (1981) and Rabbit at Rest (1990), chronicling the life of a middle-class American through the social upheavals of the 1960s and beyond. Rabbit, Run and Couples (1968) both stirred controversy with their forthright depiction of America’s changing sexual mores, and established his reputation as a peerless observer of the human complexity behind the facade of ostensibly conventional lives. His fiction, poetry and essays also show a persistent interest in moral and philosophical questions, informed by his lifelong interest in Christian theology.

Over the course of his career, he published over 60 books, including novels, collections of short stories, poetry, drama, essays, memoirs and literary criticism. The Early Stories, 1953-1975, published in 2004, collected the short fiction from the first two decades of his career. As large a volume as it is, it represents only a small part of his vast contribution to American literature. John Updike was one of very few Americans to be honored with both the National Medal of Arts and the National Medal for the Humanities.

When did you first get the idea of being a writer?

My mother had dreams of being a writer, and I used to see her type in the front room. The front room is also where I would go when I was sick, so I would sit there and watch her. Clearly she was making a heroic effort, and the things would go off in brown envelopes to New York, or Philadelphia even, which had the [Saturday Evening] Post in those years, and they would come back. And so, the notion of it being something that was worth trying and could, indeed, be done with a little postage and effort stuck in my head. But my real art interest — my real love — was for visual art, and that was what I was better at. It was considered at first. My mother saw that I got drawing lessons and painting lessons. I took what art the high school offered. I went to Harvard still thinking of myself as some kind of potential cartoonist, and I got on the Harvard Lampoon as a cartoonist actually, not as a writer, but the writing maybe was more my cup of tea. There were some very gifted cartoonists over at the Lampoon. You wouldn’t expect to find too many at Harvard, but actually they were quite good — about three of them. And, I saw that maybe there was a ceiling to my cartooning ability, but I didn’t sense the same ceiling for the writing because I had hardly given it a try. By the time I got out of Harvard I think I was determined or pretty much resolved to becoming a writer if I could.

Did you see yourself becoming a fiction writer or a nonfiction writer or both? You wrote poetry as well.

I did write a lot of light verse, and even some verse that wasn’t too light. Even I knew there was no living in being a poet, so fiction was the game. The writers I’d admired, a lot of them had written numerous essays like Robert Benchley, and I did do my share of those things when I was younger, sold a few of them. But, I found when I attempted fiction — I took a few writing courses at Harvard — it’s like sort of a horse you don’t know is there, but if you jump on the back there is something under you that begins to move and gallop. So, it’s clearly a wonderful imaginary world that you enter when you begin to write fiction. So I guess my hope was to become a fiction writer. I was prepared to fail. I was prepared to not be able to get things accepted, because I saw that happen to my mother. I knew that not everybody who tried to write actually got published, and in fact that’s kind of a long odds proposition, but I figured I’d give myself five years, and if I couldn’t get into print in five years I should know that I didn’t have what it took. But, as it turned out, I got into print pretty readily.

What was the first thing you wrote that was published?

John Updike: I actually sold a few poems in my teens to marginal magazines. I remember one poem, “The Boy Who Makes the Blackboard Squeak,” meaning the sort of naughty boy who makes the chalk squeak deliberately. I was paid maybe $5 or $10 for it, but my hope was to get into The New Yorker magazine, which began to come into the house when I was about 11 or 12.

Could you find The New Yorker in your hometown, Shillington, Pennsylvania?

John Updike: No. The New Yorker was not a Berks County thing. There may have been a few subscribers, but the newsstands did not carry it because I used to look for it. But my aunt, who lived in Greenwich, Connecticut, and was kind of a hip lady — she was my father’s sister — she thought that we, as a benighted provincial household, could use The New Yorker, and I, in fact, did use it. I loved it. I read the cartoons, but then other things too. The whole tone of the magazine was so superior to any other slick magazine, so I was aimed at The New Yorker. My writing career really begins with the day in June of ’54 when we were staying with my wife’s parents in Vermont, and word came up that there was a letter from The New Yorker, and they had taken a poem, and then a little later that summer they took a story. So rightly or wrongly, I felt kind of launched as a writer, a real writer.

They hired you not long after that, didn’t they?

John Updike: I was in Oxford the year after college with my then wife, who had been a Radcliffe girl. At that point she was a pregnant Radcliffe girl — we had a little girl in April. About that same time, Katharine White and her more famous husband, E.B. White, came to visit us in our basement flat. Katharine White was the fiction editor and a woman of great power, one of the founding members of The New Yorker in ’25, and indeed they offered me a job. Or maybe she just told me I could see Shawn, the editor, when I got back to the States. I did, and he offered me a job, and I worked in New York for about two years.

What had you published by then? One story and one poem?

That semester I think I placed four or five more stories with them, as well as quite a number of light verse poems. Light verse was in its twilight, but I didn’t know that so I kept scribbling the stuff and they kept running it for a while. So, I was kind of establishing myself as a dependable contributor and they were a paternalistic organization that tried to gather unto itself talented — whatever — writers. And it was funny to want to do that, because really about the only slot they had to offer was to write for “Talk of the Town,” the front section. We moved in, a little family of three into Riverside Drive, and I began to write these stories, and discovered I could do it, and had kind of a good time doing it. You went around in New York and interviewed people who attended Coliseum shows — kitchen appliances or whatever — and I was very good at making something out of almost nothing. But, I thought after two years that maybe I had gone as far as I could with “The Talk of the Town” as an art form, and I felt New York was a kind of unnatural place to live. I had two children at this point, and my wife didn’t have too many friends and wasn’t, I didn’t think, very happy. Well in the ’50s one didn’t think too hard about whether or not your wife was happy, sad to say, but even I could see that, so I said, “Why don’t we quit the job for a while.” I thought they’d take me back if it didn’t work out, and I’ll try to freelance up in New England, so there is where we went. We moved to a small town in New England, and I never had to go back because I was able to support myself.

Did you continue working for The New Yorker long distance? Nowadays we have email and other technology to commute electronically. How did you do it?

John Updike: Well, the technology then was the U.S. Mail, so everything took a day or two longer, but it was good enough. You could get from north of Boston to New York in a few hours on the train, so I used to go back and write a couple of “Talk” stories. It wasn’t a clean break, but it was kind of a daring thing. I felt that I would be better off in what I thought was real America. In New York everything is stratified. The people I knew were other writers. Although it’s not a major industry it was enough of a local industry that everybody was watching everybody else and I felt like I was being crowded in a way. In a small town you have good odds of being the only writer and people not really taking an interest in what you do, so you are on your own as a person, and that’s how it worked out. I thought it was successful. The children were able to move out of that pressure cooker, and they went to the public schools and there were many amenities. Free parking. All that was available in a small town.

There’s an axiom one hears about writing: “Write what you know.” Geographically, it seems, you have more or less kept to that.

John Updike: I’ve not ventured too far from what I could verify with my own eyes. I’ve tried, of course, in keeping up product, to stretch and get a little out of the American middle class. I’ve written books about Brazil, and a novel located in Africa. But basically it’s true that my own life has been my chief window for life in America, beginning with my childhood and the conflicts, the struggles, the strains that I felt in my own family.

It’s striking that the books you first gravitated to were mysteries and crime stories, and yet the books that you became well-known for are about the everyday life of ordinary people in ordinary places.

John Updike: It is odd. I love mystery novels and I’ve tried to write them. When I was in my teens I began to write a mystery novel and tried to figure out how to plot it. You sort of plot it backwards, you know. You know who did it and then you try to hide that, and I couldn’t really do it. I’m not saying I couldn’t do it if a gun was put to my head, but it felt unnatural and felt like a very minor kind of witnessing. In other words, I was willing to be entertained by others, but I didn’t want to write entertainments myself. I wanted to write books that told everything I knew, that were fully about life in my tame band of it. So quite early I began to try to become a serious writer. It’s a little puzzling. I’ve written some science fiction. That may not be well-known, but a couple of my novels are located in a hypothetical future. There is something about it that frees you up in a way. Your attempt is always to write about the world you know, but also to somehow get out of it, if only by a little jump or a trick. Something must be different so that your imagination is really engaged. You’re not just spilling your life, but you’re to some extent inventing another life.

A lot of us readers feel honored by your paying so much attention to the likes of us, not great adventures but everyday people.

John Updike: Well, in a democracy in the 20th and 21st century, if you can’t base your fiction upon ordinary people and the issues that engage them, then you are reduced to writing about spectacular unreal people. You know, James Bond or something, and you cook up adventures. The trick about fiction, as I see it, is to make an unadventurous circumstance seem adventurous, to make it excite the reader, either with its truth or with the fact that there’s always a little more that goes on, and there’s multiple levels of reality. As we walk through even a boring day, we see an awful lot and feel an awful lot. To try to say some of that seems more worthy than cooking up thrillers.

You said that writing helps the world feel more real to you.

John Updike: And I think to the reader, too.

D.H. Lawrence talks about the purpose of a novel being to extend the reader’s sympathy. And, it is true that upper middle class women can read happily about thugs, about coal miners, about low life, and to some extent they become better people for it because they are entering into these lives that they have never lived and wouldn’t want to lead but nevertheless it is, I think, the sense of possibilities within life. The range of ways to live that in part explains a novel’s value. I mean, in this day and age, so late really in the life of the genre, why do some of us keep writing them and some of us keep reading them? And I think it is, in part, because of that, that it makes you more human. It’s like meeting people at a cocktail party that you had never met and wouldn’t have cared to meet. You wouldn’t have gone out of your way to meet, but suddenly they become real to you. You understand to some extent.

You’ve also said that you write to get yourself on paper, to find out more about who you are.

John Updike: There is a certain amount of trying to be honest about what it’s like to be an American male of my age and with my general outlook. So, yes, it is a path of self understanding, But…

The fiction that I’m proudest of, insofar as one can discriminate, is that where I have made some leap. I’m best known and been most rewarded really, prize-wise and praise-wise, for the Rabbit books. And Rabbit is — he and I share roughly the same age and the same — born in the same place, but I’ve long left Berks County. He stayed there, and it’s a kind of me that I’m not. I never was a basketball star. I wasn’t handsome the way he is, and nor did I have to undergo the temptations of being an early success that way, so that for me it was a bit of a stretch. Not an immense stretch to imagine what it’s like to be Rabbit, but enough of one that it was entertaining for me to write about him, and maybe some of the self-entertainment got into the book. In other words, you can kind of walk around. I can kind of walk around Rabbit in a way it’s hard to walk around, say, the autobiographical hero of some of your short stories, where it’s your twin, you know, and you’re attached. It’s the idea of breaking that attachment, I think, that matters and where the fiction really begins to take off when you can get somebody else in your sights.

Did you think you were through with Rabbit after the first novel?

John Updike: Yeah. I didn’t write that with any idea of a sequel, but the book does kind of end on a hovering note, and enough people asked me, “Well what happened?” Not too many, but a few put a bee in my bonnet. When I had run out of subjects, I thought…

“Well, why not tell what happened and bring Rabbit back.” This was during the late ’60s, when there was a lot of turmoil in America, and so I brought him back this time as kind of an everyman who is witnessing the pageant of protest and disturbance, distress, drug use, everything, almost everything was in that book, including the moon shot. In fact, the moon shot is kind of a central event in it, so that the Rabbit who came back the second time was a much more purposefully representative American than my initial Rabbit. He was just, you know, a high school athlete who had nowhere much to go after he graduated, whereas the second Rabbit was kind of a growing man trying to learn in a way. I’ve always seen Rabbit, and indeed Americans in general, as learners, as willing to learn. They may be slow to learn, but there is an openness to our mindset that I think enables us to overcome our mistakes or our prejudices and move forward. Certainly the world now is so much more open. I mean, it is easy to be sentimental about the ’30s and ’40s and the wartime solidarity and all that, but there was so much racism, sexism, everything. It was a brutal world compared to the one we’re trying to make now.