A person knows when it just seems to feel right to them. Listen to your heart.

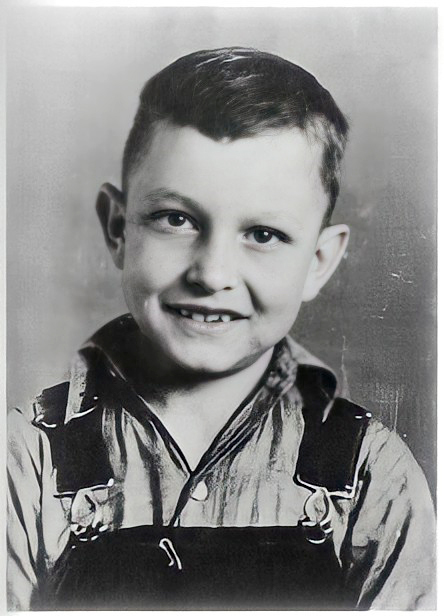

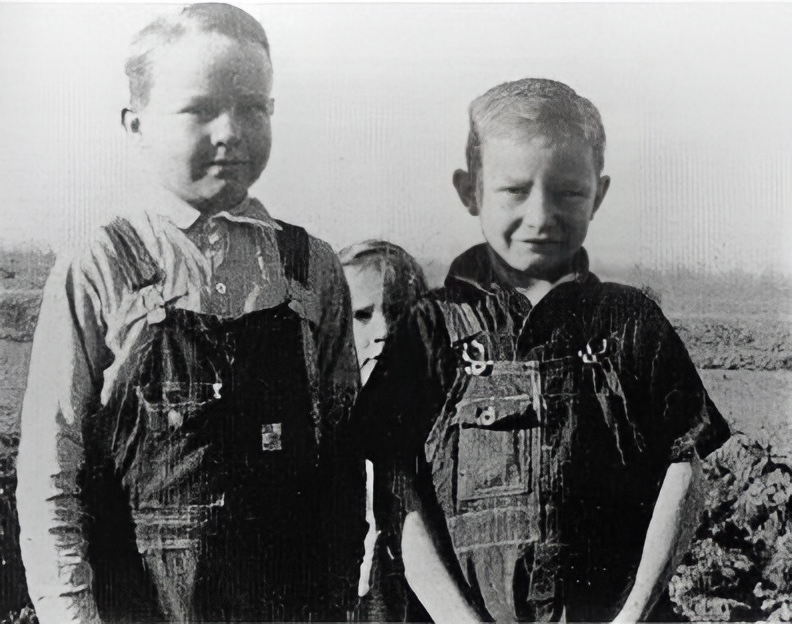

Johnny Cash was born in the small town of Kingsland, in the hill country of southern Arkansas. Life had always been difficult there, but when the Great Depression destroyed the fragile agricultural economy of the region, Johnny’s parents, Ray and Carrie Cash, could barely earn enough to feed their seven children.

In 1935, the New Deal administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt encouraged marginal farmers from the hill country to resettle in the more fertile soil of northeastern Arkansas. The Cash family took the government up on this offer and made the move. Working together, they cleared 20 acres of land to grow cotton. Johnny worked side by side with his parents on the farm.

In the evenings when the day’s chores were done, the Cash family gathered on their front porch. Johnny’s mother, Carrie, played guitar, and the whole family sang hymns and traditional tunes. Johnny loved his mother’s playing and singing, and he was entranced by the country and gospel singers he heard on an uncle’s battery-powered radio. By 12 he was writing poems, songs and stories.

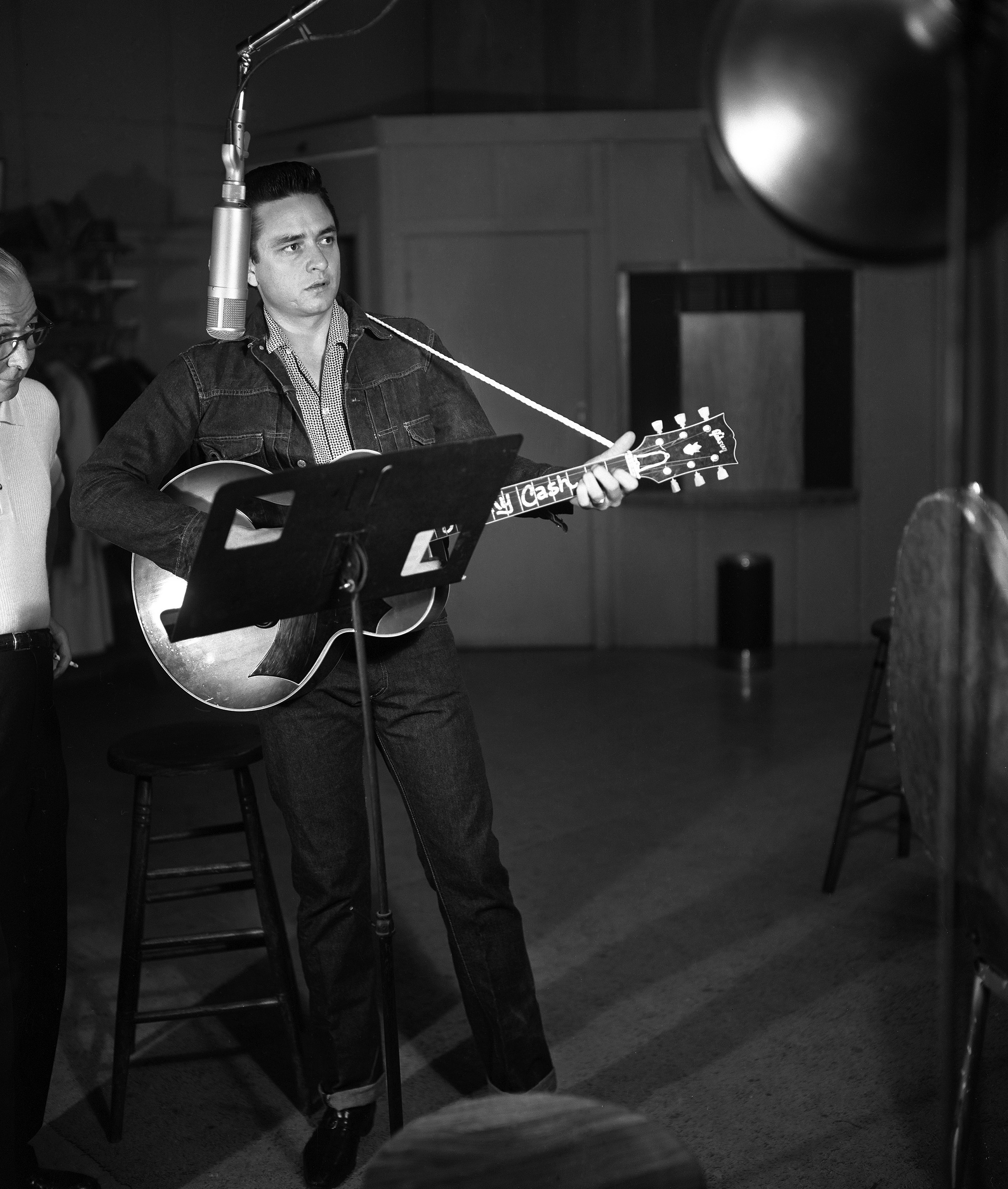

He took his first non-farm job at 14, carrying water for work gangs, but he had set his heart on a music career. He entered talent contests and sang anytime and anywhere people would listen. When Johnny Cash graduated from high school in 1950, there was no question of his going to college. The Korean War was raging, and he enlisted in the United States Air Force. He was serving with the Air Force in Germany when he bought his very first guitar. With a few of his buddies, he started a band called the Barbarians to play in small night clubs and honky tonks around the air base. When his hitch in the service was over, Johnny Cash moved to Memphis, where he sold appliances door-to-door while trying to break into the music business.

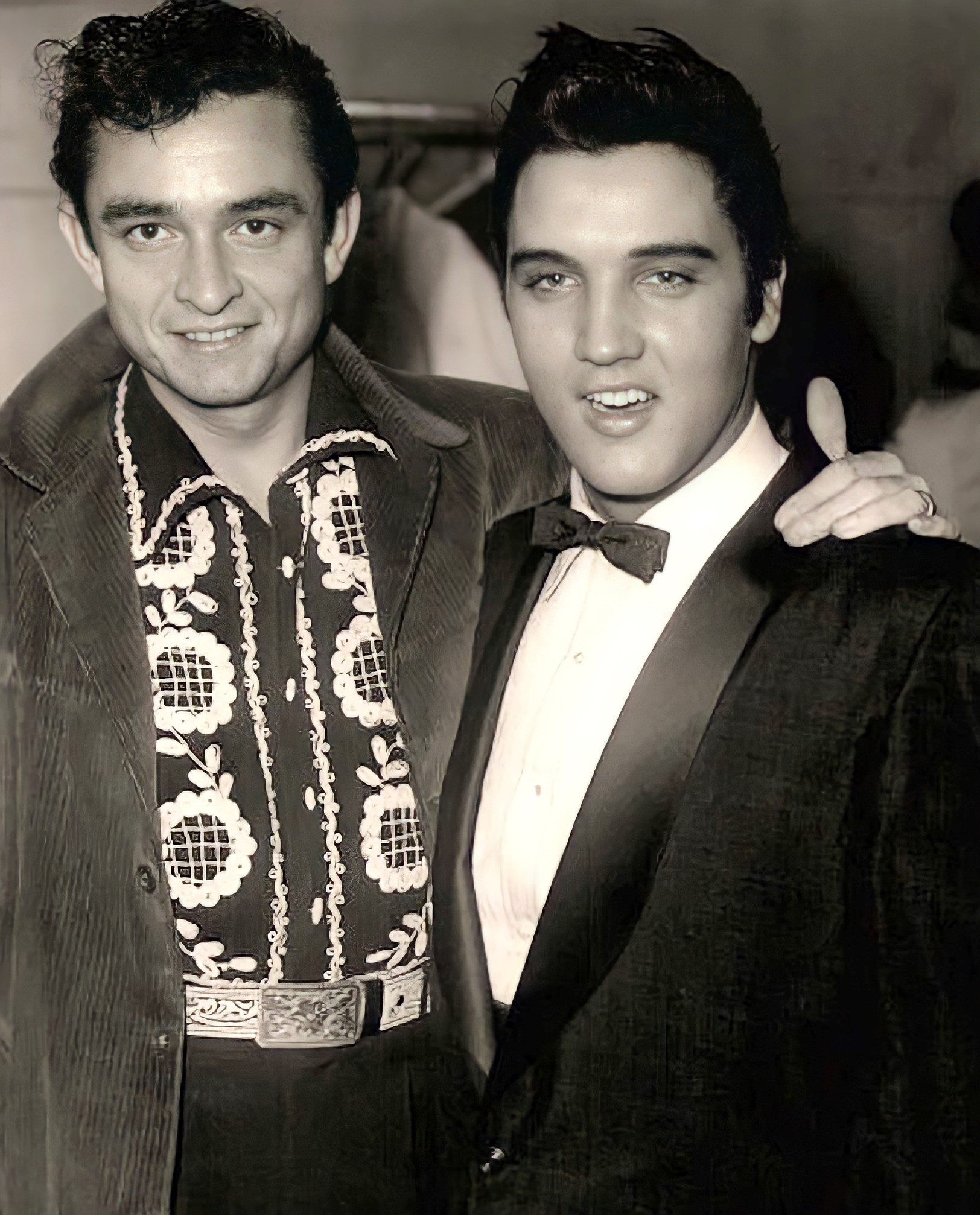

In 1954, he was signed to the Sun Records label owned by Sam Phillips, who had also discovered rock ‘n rollers Elvis Presley and Jerry Lee Lewis. Philips was impressed with the song “Hey Porter” Cash had written when he was returning home from the Air Force. When Phillips wanted a ballad for the b-side of “Hey Porter,” Cash wrote “Cry, Cry, Cry” overnight. The single sold over 100,000 copies in the southern states alone. Johnny Cash and his sidemen, the Tennessee Two, began touring with Elvis Presley and the other Sun Records artists. They performed on the Louisiana Hayride radio program, and Johnny Cash made his first television appearances on local programs in the South.

With his second recording, “Folsom Prison Blues,” Johnny Cash scored a national hit. In 1956, “I Walk the Line” was a top country hit for 44 weeks and sold over a million copies. Johnny began to appear at the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville, the Mecca of country music.

His popularity increased so rapidly that, by 1957, country music publications were rating him the top artist in the field. And by 1958, Johnny Cash had published 50 songs, and pop artists far from the country music mainstream were recording Johnny Cash tunes. He had sold over six million records for Sun when he moved to the New York-based Columbia Records label. Johnny himself moved to California and brought his parents along.

By the end of the 1950s, the LP, or long-playing record, was emerging as the dominant form for recorded music. The 1959 album Fabulous Johnny Cash sold half a million copies, as did Hymns and Songs of Our Soil, and the single “Don’t Take Your Guns to Town.” Concert tours took Johnny to Europe, Asia and Australia. He began to appear as an actor in television westerns. Even as his concert fees escalated, he took time from his schedule to perform free of charge at prisons throughout the nation.

The 1960 single “Ride This Train” won a gold record, as did the 1963 album Ring of Fire and the 1968 LP Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison. In 1964, Cash, who was one-quarter Cherokee Indian, recorded the album Bitter Tears on Native American themes. That same year, he appeared at the Newport Folk Festival, breaking down a perceived barrier between the genres of country and folk music. At Newport, he made the acquaintance of Bob Dylan. Dylan featured Cash on his own Nashville Skyline album, and Cash recorded several of Dylan’s songs.

As the 1960s wore on, incessant touring took its toll on the singer. To keep up with his hectic schedule, he had become dependent on tranquilizers and the amphetamine Dexedrine. He gave up his home in California and relocated to Hendersonville, Tennessee, near Nashville. When his health recovered and he had freed himself from his chemical dependency, Johnny Cash married June Carter of the legendary Carter Family, whose radio broadcasts had inspired Johnny when he was growing up in Arkansas. With June at his side, he made a triumphant comeback, selling out Carnegie Hall and breaking the Beatles’ attendance record at London’s Palladium.

In 1969, public television broadcast the documentary film Cash!, and the networks became interested in a more regular TV presence. The Johnny Cash Show premiered on ABC television in the summer of 1967 and became part of ABC’s regular schedule the following January. This prime time television variety show ran until 1970 and presented guest artists as varied as Ray Charles, Neil Young, Glenn Campbell, Stevie Wonder, Louis Armstrong, Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, and The Who.

Renewed sales of his records made Johnny Cash a millionaire. He used his earnings to support mental health associations, a home for autistic children, refuges for battered women, the American Cancer Society, YWCA, Youth For Christ, Campus Life, and humane societies around the country. At the same time, he played benefits for Native American causes and endowed a burn research center in memory of his former guitarist Luther Perkins, who had died in a fire. In addition to performing for prison inmates, Johnny Cash campaigned for prison reform, corresponded with inmates and helped many return to society. His 1975 autobiography Man in Black sold 1.3 million copies. He surprised fans and critics alike in 1986 by writing Man in White, a bestselling novel based on the life of St. Paul. In 1987, Johnny Cash received three multi-platinum records for previous sales of over two million copies each of Folsom Prison, San Quentin, and his collection of Greatest Hits.

In 1994, his recording career revived with the release of American Recordings, the first of four Grammy Award-winning collections of extremely diverse material, ranging from folk songs to his own compositions and songs by contemporary artists such as U2 and Nine Inch Nails.

Over the course of his career, he received 11 Grammy Awards. He was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and the Songwriters’ Hall of Fame. He received the Kennedy Center Honors, the National Medal of the Arts, and the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.

His wife of 35 years, June Carter Cash, died from complications following heart surgery in May 2003. Johnny Cash followed her in death four months later, succumbing to respiratory failure after a long struggle with diabetes. Even in death, Johnny Cash remains a powerful force in American culture. Only two years after his passing, a motion picture based on his life, Walk the Line, enjoyed worldwide critical and popular success. The film generated a revival of interest in his life and work, assuring that another generation would find inspiration in the timeless sound of the Man in Black.

American VI: Ain’t No Grave, released February 26, 2010 on what would have been Cash’s 78th birthday, is the last of the American Recordings series Cash was working on with producer Rick Rubin months before his death.

For over 40 years, Johnny Cash wrote and sang about the lives of hard-scrabble farmers, homeless drifters, broken-down cowhands, broken-hearted lovers and men behind bars. He gave a voice to the lonesome and the lost, the dispossessed and the disillusioned. He came by this sympathy naturally, growing up on his family’s cotton farm in rural Arkansas in the depths of the Depression. America first discovered Johnny Cash in the mid-1950s, and since then people around the world have heard in his voice an unmistakable honesty about the hard facts of life, love and faith.

Johnny Cash placed at least two hit singles a year on the country music charts for 33 years running, and over 53 million copies of his record albums have been sold since 1959. Songs like “Folsom Prison Blues” and “I Walk the Line” have become part of the national inheritance. In his eighth decade, he won over a new generation of admirers with his interpretations of songs ranging from traditional ballads to the dark and moody songs of contemporary rock bands.

Johnny Cash and his songs have become an institution in our national life. Thanks to his recordings, the Man in Black with the cavernous baritone voice will remain as much a part of the American scene as the Mississippi River or the Rocky Mountains.

When did you first have a vision of what you wanted to do?

Johnny Cash: I think the first time I knew what I wanted to do with my life was when I was about four years old. I was listening to an old Victrola, playing a railroad song. The song was called “Hobo Bill’s Last Ride.” And I thought that was the most wonderful, amazing thing that I’d ever seen. That you could take this piece of wax, and music would come out of that box. From that day on, I wanted to sing on the radio. That was the big thing when I was growing up, singing on the radio. The extent of my dream was to sing on the radio station in Memphis. Even when I got out of the Air Force in 1954, I came right back to Memphis and started knocking on doors at the radio station.

I grew up in the ’40s and I heard all these great speeches, like Winston Churchill. His most famous, or infamous commencement exercise speech was one that consisted of seven words. He stood before this graduating class and said: “Never, never, never, never, never give up.” And then somebody else said: “Every day in every way I’m getting better and better.” I didn’t especially believe that about myself, but I said it every day and I made myself believe it and it worked. I persevered. I never gave up my dream to “sing on the radio.” And that dream came true in 1955.

Tell us how that dream came true. Who gave you your first big break?

Johnny Cash: Sam Phillips, at Sun Records. There was a label called Sun Records in Memphis that was pretty hot, with Elvis Presley, and two or three locally well-known country acts, and some black, blues and gospel singers. When I got out of the Air Force, I went and knocked on that door and was turned away. I called back for an interview three or four times, was turned away. So one morning I found out what time the man went to work. I went down with my guitar and sat on his steps until he got there. And when he got there I introduced myself, and he said, “You’re the one that’s been calling.” I said, “Yeah.” You know, I had to take the chance, he was either going to let me come in, or he was going to run me off, turn me down again. Evidently, he woke up on the right side of the bed that morning. He said, “Come on in, let’s listen.” So he did. He said, “Come back tomorrow and bring some musicians.” So I went down to the garage where I worked, where my brother Roy worked, and was introduced to two musicians down there. Brought them back to the studio and the next day was our first session. We recorded, and released the songs that we recorded the second day. It was very simple back then. You didn’t worry about arrangements. It was one-track recording.

When you were young, was there a particular book that you read that was important to you?

Johnny Cash: I read a book when I was about 12 years old about an Indian named Lone Bull. Lone Bull had tried to go out and kill a buffalo. He slipped out of the village, against his father’s wishes and went out. He was going to be a hero and kill a buffalo and bring it back to the village, so his family and the other people could have meat. And the elders of the village knew about the buffalo herd. They knew it was there, and they were making plans to cut into the herd and cut off some buffalo and kill them and have meat for the whole winter and into the next spring.

Lone Bull wanted to be a hero. He went out with his bow and arrow and killed a calf, and ran the herd off into the next state. He drug this calf home, his family was fed, but they were ostracized from the village. They had to leave the village. Lone Bull became a wanderer, until he found a village that would take him in. In that next village where he was taken in, he organized the buffalo hunt that winter, and they had more meat than this village had ever had before.

So, I learn from my mistakes. It’s a very painful way to learn, but without pain, the old saying is, there’s no gain. I found that to be true in my life. You miss a lot of opportunities by making mistakes, but that’s part of it: is knowing that you’re not shut out forever, and that there’s a goal there that you still can reach. Lone Bull’s philosophy was, “I’m kicked out of this village, but I will grow up and I’ll come into another one and I will do what I set out to do. That was feed the people.” So I’m feeding my people right now.

A lot of people let failure get them down. You’re saying that you’ve got to move on.

Johnny Cash: You build on failure. You use it as a stepping stone. Close the door on the past. You don’t try to forget the mistakes, but you don’t dwell on it. You don’t let it have any of your energy, or any of your time, or any of your space. If you analyze it as you’re moving forward, you’ll never fall in the same trap twice, which I can’t say that I haven’t been guilty of doing. But my advice is, if they’re going to break your legs once when you go in that place, stay out of there.

Was there a particular person that was very important to you as a kid?

Johnny Cash: In my little world, in northeast Arkansas on a cotton farm, it was my brother Jack. He was my inspiration. He was two years older than I and he was killed at the age of 14. I always wanted to be like him. He was a strong person, he was a Bible student, he was in perfect shape, physically. I always wanted to be like him. And when he died, my best friend was still my mother, and she always encouraged me to sing. As a matter of fact, we were very poor, and she took in washing from the school teachers, washed their clothes to make money to give me singing lessons, voice lessons. After about three lessons the voice teacher said, “Don’t take voice lessons. Do it your way.” I was glad for my mother that I didn’t have to take them.

How about your father?

Johnny Cash: My father was a man of love. He always loved me to death. He worked hard in the fields, but my father never hit me. Never. I don’t ever remember a really cross, unkind word from my father. He was a good, strong man who provided for his family. That was his sole purpose in life when I was growing up.

It sounds like your parents were supportive of your path.

Johnny Cash: They were. Especially my mother. She was the most musically inclined in the family. She played a little guitar and piano, and loved to sing. From the time I started trying to sing when I was a kid, she always encouraged me to do it. I told her when I was about 12 that I was going to sing on the radio. She encouraged that dream.

Musically, my inspirations were whoever was popular on the radio: Jimmy Rodgers, the Carter Family — which is my wife’s family — black blues, black gospel and white gospel groups, like the Blackwood Brothers, and the Chuckwagon Gang. Or cowboy singers like Gene Autry, and Bob Wills. I liked the image of the man with the white hat correcting all the wrongs out there.

Your voice does not sound like anybody else’s voice. You must have had a lot of confidence that you had a voice.

Johnny Cash: I did.

It goes back to that music teacher when I was 12 years old. After the third lesson, I was singing some popular country song of the day. I forget the name. I think it was a Hank Williams, no, it was too early for Hank Williams, I guess. Whatever the song was, I didn’t sing it like the artist had sung it on the radio. And she said, “You’re a song stylist.” She said, “Always do it your way.” And from the age of 12, I didn’t forget that. But that was the way I had to do it, because it was the way it was with me. I had to do it my way. I couldn’t read those notes, singing those great songs, like a lot of those singers could, but I could do it my way — the way it felt good to me. And that’s what music is all about, emotion.