We weren't poor, we just didn't have any money.

Johnny Mathis was born in the small town of Gilmer, Texas, but the family relocated to San Francisco before he reached school age. His mother, Mildred, worked as a housekeeper, his father Clem as a chauffeur. Of the seven children, Johnny took the greatest interest in music, to the delight of his father, who sang and played the piano. Clem Mathis taught Johnny his first songs, and soon the boy was singing in a church choir, at school assemblies, and on local television.

By age 13, he was studying voice seriously with teacher Connie Cox, who gave him a thorough grounding in classical vocal technique. The young Johnny Mathis was also an outstanding athlete, playing on the George Washington High School basketball team and competing in track and field. After high school, he enrolled at San Francisco State to study English and physical education, with the intention of becoming a teacher. In college, he continued to compete in track and field, excelling at the high jump. He also began to sing in local nightclubs with the jazz band of his friend Virgil Gonsalves. One club owner, Helen Noga, was so impressed she offered to manage the young man’s singing career. Soon Mathis was singing every weekend.

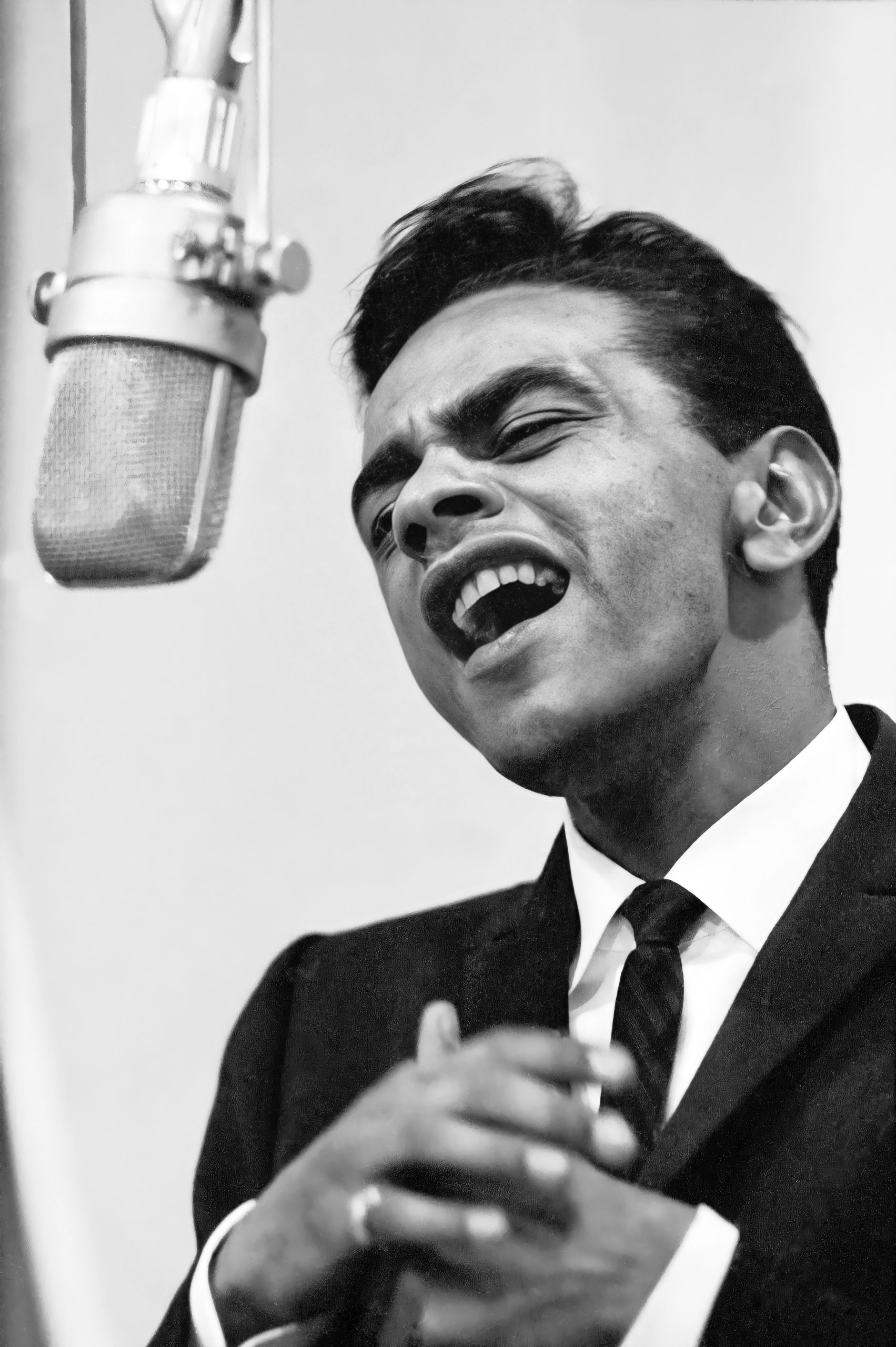

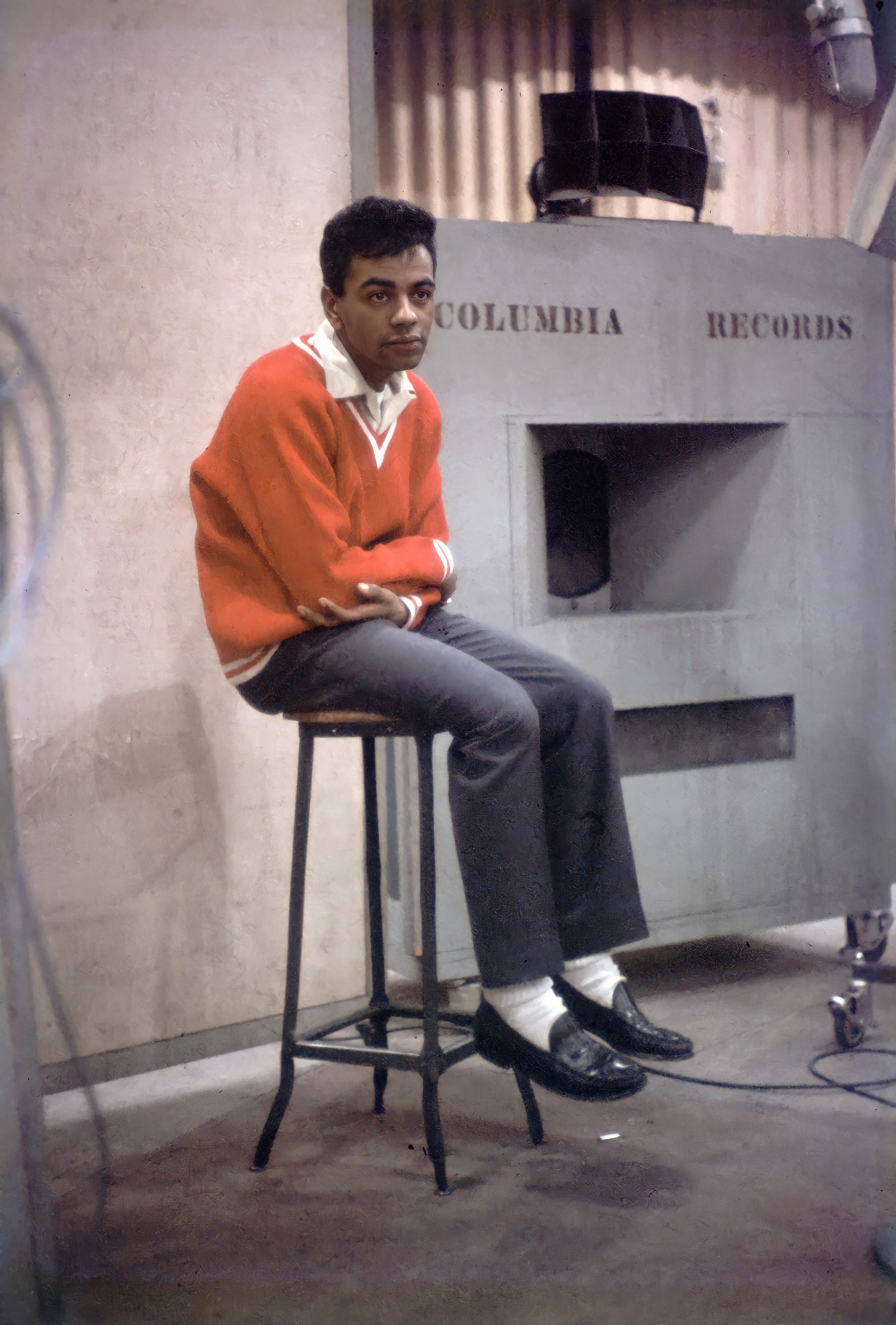

Noga invited record producer George Avakian to hear Mathis sing. Avakian, who headed the jazz department at Columbia Records, sent a famous telegram to the label’s New York office: “Have found phenomenal 19-year-old boy who could go all the way. Send blank contracts.” After signing Mathis to a contract with Columbia Records, Avakian returned to New York to plan the singer’s recording debut.

Meanwhile, Johnny Mathis returned to his studies and continued to attract the attention of the local press with his feats as a high jumper. He was invited to attend the 1956 Olympic trials, but by then, Avakian had scheduled a recording session in New York, and Mathis had a difficult choice to make. Music won out, and Johnny Mathis traveled to New York City to record his first record in March 1956. Avakian, who had only heard Mathis performing in a jazz context, produced an album in a similar vein, Johnny Mathis: A New Sound In Popular Music. Despite Johnny’s obvious talent, and the accompaniment of first-rate musicians, the record attracted little attention. Mathis remained in New York over the summer, performing in the city’s major nightclubs while Columbia reconsidered their approach.

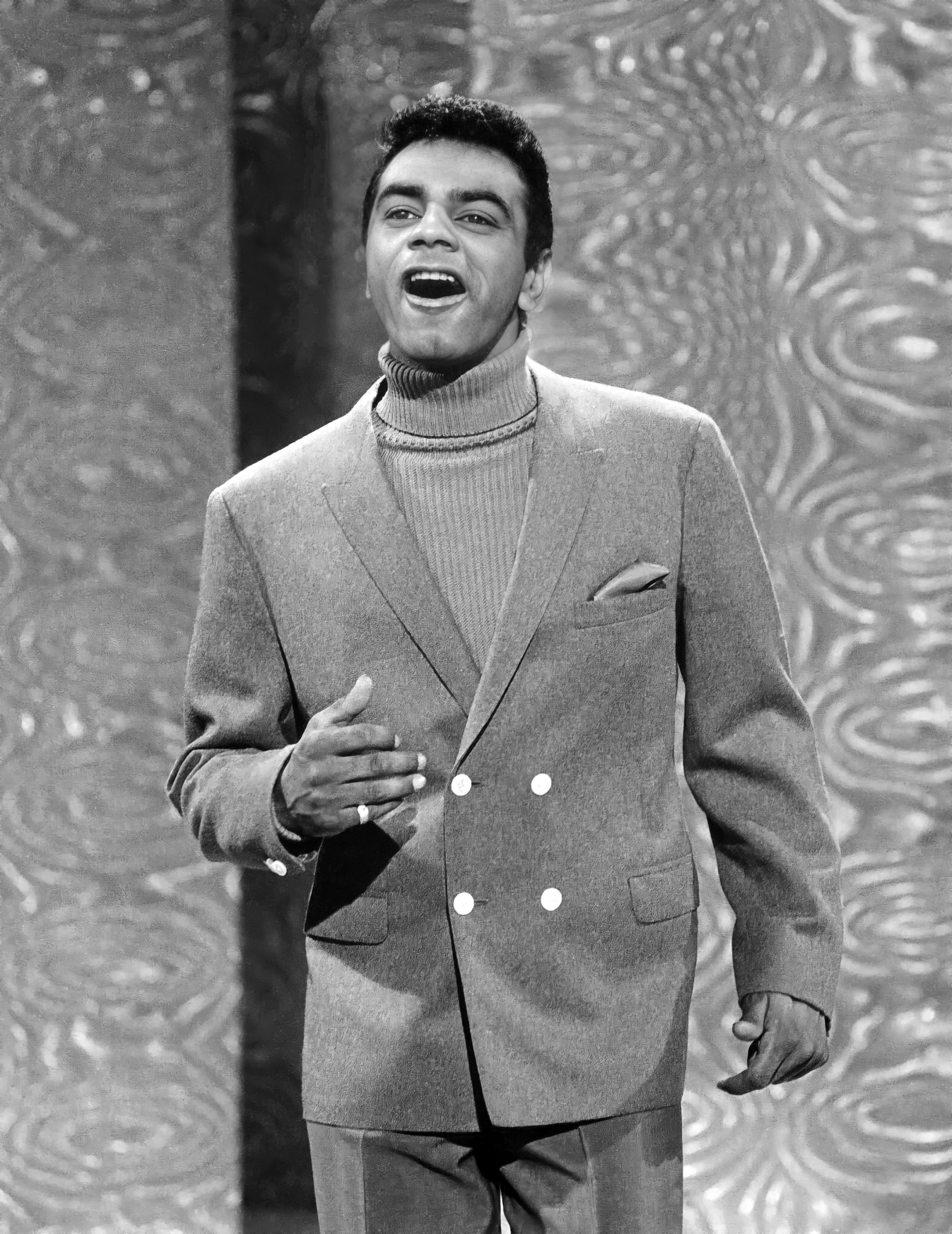

Mitch Miller, the head of A&R (artists and repertoire) at Columbia, wanted to hear Mathis singing romantic ballads in a mainstream popular style, emphasizing the beauty of his voice and the clarity of his diction, rather than trying to make a jazz artist of him. Miller produced Mathis’s second session, that autumn, and came up with two hit singles, “Wonderful! Wonderful!” and “It’s Not for Me to Say.” Soon Mathis made his first motion picture appearance, singing “It’s Not for Me to Say” in the MGM film Lizzie. In June 1957, Mathis appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show for the first time, and the singles he had recorded with Miller soon became major hits. Later that year, he recorded his biggest hit of all, “Chances Are,” which became the bestselling record in the country. It was followed quickly by his third Top Ten single, “The Twelfth of Never.”

In 1958, Columbia released a Johnny Mathis “Greatest Hits” collection. In subsequent years, such albums became a recording industry staple, but at the time they were unheard of, especially for a singer who had only been recording for two years. Johnny’s Greatest Hits became one of the bestselling records of all time, remaining on Billboard magazine’s Top Albums chart for nearly ten years. The same year saw the release of his first Christmas album; Merry Christmas would eventually sell over six million copies. Mathis made his second film appearance that year, singing the title song in A Certain Smile.

Helen Noga and her husband, John, moved to Beverly Hills in 1958, and Mathis joined them, living with the Noga family when he was not on the road performing. The year 1959 saw the release of another Mathis hit, the Erroll Garner song, “Misty.” Columbia Records kept Mathis busy recording albums of romantic ballads, show tunes and pop standards. More hits followed, including “Gina” and “What Will Mary Say,” but Mathis became dissatisfied with the direction of his career. In 1963 he moved from Columbia to Mercury Records and recorded a second Christmas album. The following year he brought legal action to be released from his management contract. Breaking with the Nogas, Mathis bought a house in the Hollywood Hills that would remain his principal residence for many years.

Mathis returned to Columbia Records in 1967, with a greater degree of control over his career through production companies he founded with a friend and business partner, Ray Haughn. The 1960s brought enormous changes to the music industry, and Mathis scored fewer hit singles than before, but his albums continued to sell phenomenally well. At one point, he had five albums on the charts simultaneously.

A demanding schedule of recording and touring eventually exhausted the singer’s formidable energy. An unscrupulous doctor prescribed amphetamines and other prescription drugs to keep Mathis going on the road. His efforts to quit the addictive medications without assistance undermined his health further. The combination of prescription drugs and excessive drinking threatened to derail his career. Mathis credits loyal friends with persuading him to seek the help he needed to free himself from his addictions.

A 1976 single, “When a Child Is Born,” topped the UK pop charts and sold over six million copies worldwide. In 1978, Mathis returned to the U.S. pop music charts with “Too Much, Too Little, Too Late,” a duet with R&B singer Deniece Williams. The song swept the country, and 20 years after he first topped the charts with “Chances Are,” Mathis scored his second number one hit. The success of the song led Mathis to record a series of duets with singers such as Dionne Warwick, Natalie Cole and Gladys Knight. His 1978 album, You Light Up My Life, sold over two million copies.

Since overcoming his health problems, Mathis has made more time for hobbies and charitable pursuits. From childhood days, he enjoyed cooking, and over the years he has developed a formidable expertise in the kitchen. In 1982 he shared this talent with the public in a cookbook, Cooking for You Alone. The same year, he founded the Johnny Mathis Invitational Track and Field Meet at San Francisco State University. An extremely accomplished golfer, he hosted his own golf tournament, the Johnny Mathis Seniors PGA Classic, held in Los Angeles in 1985 and ’86. He later hosted a charity golf tournament, the Shell/Johnny Mathis Golf Classic, in Belfast, Northern Ireland.

In 1984, Mathis’s longtime manager and business partner Ray Haughn died. Since then, Mathis has managed his career himself, from his offices in Burbank, California. Since turning 65 in the year 2000, Mathis has generally limited himself to between 50 and 60 live performances a year. He has continued to create successful recordings, including his five Christmas albums. It is estimated that Johnny Mathis has sold over 350 million records worldwide, more than any recording artists other than Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley. To date, 73 of his nearly 100 albums have reached the Billboard Top Album charts, with 13 Gold Records (sales of over 500,000) and eight platinum, (sales of over a million copies), including three with sales of over two million. Of his 200 singles, 71 have charted worldwide. His recordings of “Chances Are” and “Misty” have been inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame. In 2003 the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences presented him with its Lifetime Achievement Award.

The year 2006 was the 50th for Johnny Mathis as a recording artist, an anniversary marked by the release of the album Johnny Mathis Gold: A 50th Anniversary Celebration and a public television special, Wonderful, Wonderful. The same year, Mathis was honored by the Society of Singers with its Ella Award, named for Ella Fitzgerald, one of his early inspirations. Over the years, Mathis has recorded Spanish and Brazilian songs as well as jazz, pop, Broadway, soul, even disco. In 2010 he recorded his first country album, Let It Be Me — Mathis in Nashville. The Grammy-nominated record included duets and collaborations with singers Alison Krauss and Vince Gill. In the seventh decade of his extraordinary career, Johnny Mathis remains the world’s bestselling living recording artist.

Johnny Mathis was only 19 years old when a Columbia Records executive heard him singing in a San Francisco nightclub and decided to sign the teenage singer on the spot. After his first album, recorded in a jazz style, failed to register with the public, producer Mitch Miller guided Mathis to a more straightforward romantic sound, leading to hits like “Wonderful! Wonderful!” and “It’s Not for Me to Say.”

A series of appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show made Mathis a national star, and at age 22 he had the number one record in the country, “Chances Are.” In 1958, only two years into his recording career, he became the first artist to release a “Greatest Hits” collection. One of the bestselling records of all time, Johnny’s Greatest Hits inaugurated the custom of “Greatest Hits” collections that continues to this day. Johnny Mathis continued to record Top 40 hits in each of the first four decades of his career, reaching number one again in 1978 with “Too Much, Too Little, Too Late.”

His velvet voice and impeccable phrasing have captured the hearts of listeners the world over. His mastery of American song has earned him the enduring affection of his public and the profound respect of his peers, who have honored him with the Recording Academy’s Lifetime Achievement Award, and a place in the Grammy Hall of Fame. For half a century, through all the changes in musical fashion, Johnny Mathis has sounded a pure note of romance, and brought magic to millions.

How did you start singing?

Johnny Mathis: My dad was an accomplished singer and pianist but he played by ear. He sang because it was something that he loved to do. He never had a career or anything singing. But he just had a wonderful way about him that was very pleasing, very pleasant. It wasn’t intimidating for me as a little kid, and from the time I was five or six years old I was learning songs that he taught me. My dad said, “Son, let’s sing this song.” And he said, “How would you like to learn some more songs? How would you like to do this with your voice? How would you like to do that?” That’s sort of the way he treated me.

Do you remember any of his songs?

Johnny Mathis: Oh sure. Yes.

“Molly and me…

And baby makes three…

We’re happy in my blue heaven.”

He played the piano quite well and he would play these wonderful…

“Going to Kansas City…

Kansas City, here I come.”

Dad never sang above a whisper. He always whispered his songs. He was that polite! I think it was just a sense of politeness about him. But he was quite good at what he did. Yeah, I learned from him. And every time I hear myself on records, I hear my dad.

Was your voice then the same voice we hear now?

Johnny Mathis: No, I sounded like a little girl! I heard myself for the first time, and I shared an old machine that made recordings. You would have to gather the residue from the vinyl, and I sounded like a little girl. I was very disappointed, because my heroes at the time were baritone singers, people like Billy Eckstine, Nat King Cole, et cetera.

Take us back to the beginning. Where was this?

Johnny Mathis: I was born in Texas in a little town called Gilmer. I don’t remember too much about it because my dad took the family from — I guess I was about four when I left Gilmer, and we went to San Francisco and I started my schooling there, went to Roosevelt Junior High School. I went to Emerson Grammar School and then on to George Washington High School. Yes, I did sing. I sang for a year and a half to pay for all my books and my tuition at San Francisco State College, and I got odd jobs. But before that, when I was about 12, my dad asked me if — my dad was a good singer and I learned all of his songs — and then in order to progress a little bit more, he asked me if I’d like to take voice lessons. So we looked around San Francisco for someone to help me out and we found a wonderful lady in Oakland. Her name was Connie Cox. And Connie taught me for about seven years. Voice lessons free of charge. I would clean her apartment and run errands for her, and she was the angel. She was the one who guided me and said, “This is what I think you can do.”

Did you have siblings growing up with you in San Francisco?

Johnny Mathis: My mom and my dad raised seven of us: six brothers and sisters. I’m right in the middle, three older, three younger. I cherish my brothers and sisters. We had a lot of fun together. None of them really got too involved in music. My youngest brother, Michael, was quite enamored with it. He had a little band and sang and played for quite a while, and then he became ill and wasn’t able to play anymore.

Was he the youngest?

Johnny Mathis: Yes, he was the youngest of seven.

Did he want to be just like his big brother?

Johnny Mathis: No, he didn’t like my songs. He liked rhythm and blues, and did quite well with it. He was very talented, but he got sick very early on in life.

How did your parents manage to raise such a large family during that time?

Johnny Mathis: You know, I think about that now and I’m amazed, because there was never a time that we didn’t have what we needed. We weren’t poor, we just didn’t have any money! So my mom and my dad worked as domestic workers for all their lives, and supported the family that way. They were fortunate to work for people who were quite well off, so we had a lot of stuff that was given to us. I was, for instance, very fortunate to be taken under the wing by one of their employers. His name is Garfield Merner, and he was on the board of several Southern colleges and offered me scholarships. But unfortunately, I was never able to take advantage of them, because I only stayed a year and a half at San Francisco State College before I got an opportunity to make my first recording.

You speak very warmly of your parents.

Johnny Mathis: I love to talk about my mom and my dad, because they were my best friends. We had a wonderful, extraordinary relationship. They were the kindest, most generous people I’ve ever known, and I don’t know how they managed with seven kids. I just don’t know how.

They must have been very proud of you. I’m sure the whole family was.

Johnny Mathis: The thing that I did, sort of inadvertently, was I wanted to include them in my life a little bit more, so I made my mom and my dad my fan club presidents. They would get all this mail from all over the world and sit down into the wee hours of the morning, writing in longhand these replies to all of these people from far-off lands and what have you.

Was this at the beginning of your career, when you were only 19?

Johnny Mathis: Yes, I was 19, and I always wanted to include them. They were inclusive to all of their children. There was no mystery about what they did, or about the family. There was no discord. We were all just kind of people who got along together a lot. I think it’s helped me a great deal in my life.

Living in San Francisco you can meet people of many different ethnic backgrounds. Were you one of the few African American families in your neighborhood or in your school?

Johnny Mathis: Yes. We were fortunate because we lived and went to school with a lot of Chinese from Chinatown. San Francisco, I think, has the largest Chinese settlement outside of the Orient. So really we were accustomed to seeing and interacting with people of different races. We never really had any problems in that respect, even later on after I became an entertainer.

Those were difficult times for many African Americans, entertainers or not. What was it like for you? You became famous at such an early age.

Johnny Mathis: Yes, I did get famous at an early age because of my recordings. And I was so fortunate, I followed people like Lena Horne, Billy Eckstine, and Nat King Cole, and people — icons in the music business when I was growing up — and eventually I got to meet all of them and even become close friends with them. But they are the ones who did all the work for me as far as race relations were concerned. Fortunately they were all intelligent, bright people who were looking to improve relationships between black entertainers and white entertainers and just in general, the public as a whole. So I had good role models to follow. But they were the ones who went to the nightclubs and to the concert hall before me and paved the way. When I came along I really was judged by my music and nothing more.

What was your mom doing when your dad was encouraging you to sing? Did she want you to do something else?

Johnny Mathis: No, Mom was right there all the time, but she was always five or six steps in the background. She loved — not to participate — but to be someone who enjoyed watching. She was not musical, so she was a little bit fascinated by it all.

She must have been quite encouraging in her way.

Johnny Mathis: She was there at all times. The greatest thing I think that I learned from her — besides the obvious things, her humility, her generosity — is I learned to cook all my own food at an early age, and I cooked all my life.

Are you still cooking?

Johnny Mathis: Oh yes.

What are your favorite things to cook?

Johnny Mathis: Whatever someone else doesn’t cook better! I’m not above going to a restaurant that really knows what they’re doing, but I’ve cooked all my life.

You’re a man of many talents.

Johnny Mathis: Men make really good chefs, I think.

Was there a particular song or book that inspired you as a young person?

Johnny Mathis: I think the thing that motivated me most musically — and that’s about all I can think of, because my life has been all about music — the rest of the things I’ve sort of learned along the way. For instance, how to take care of my body physically, so that I’ll be able to sing when I’m required to. That I learned at an early age, because of my athletics in college and high school. So I learned to exercise regularly so that I could be strong physically to support the tones. I was fascinated from a very early age by opera singers. They were the ones that I listened to, and that my teacher Connie Cox played for me ad nauseam. She felt that if I could learn from them the technique of producing the tones properly — not just producing them, but producing them so that I wouldn’t do harm to my vocal cords — that was the thing that was important to her. And that was the thing that has stood me in good stead all these years.