I'm drawn to failure. I feel that I'm contending with it constantly in my own life.

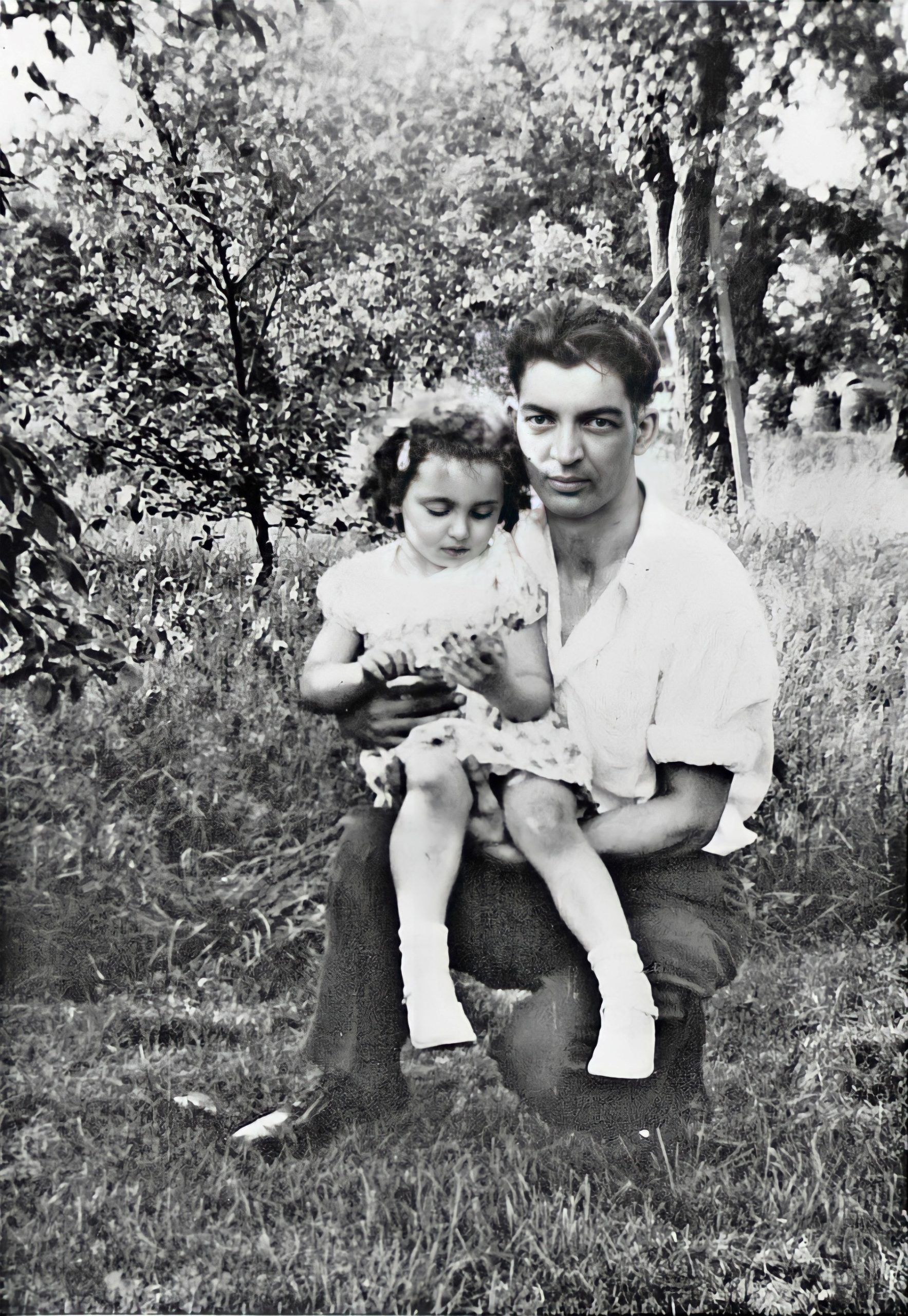

Joyce Carol Oates was born in Lockport, New York. She grew up on her parents’ farm, outside the town, and went to the same one-room schoolhouse her mother had attended. This rural area of upstate New York, straddling Niagara and Erie Counties, had been hit hard by the Great Depression. The few industries the area enjoyed suffered frequent closures and layoffs. Farm families worked desperately hard to sustain meager subsistence. But young Joyce enjoyed the natural environment of farm country, and displayed a precocious interest in books and writing. Although her parents had little education, they encouraged her ambitions. When, at age 14, her grandmother provided her with her first typewriter, she began consciously preparing herself, “writing novel after novel” throughout high school and college.

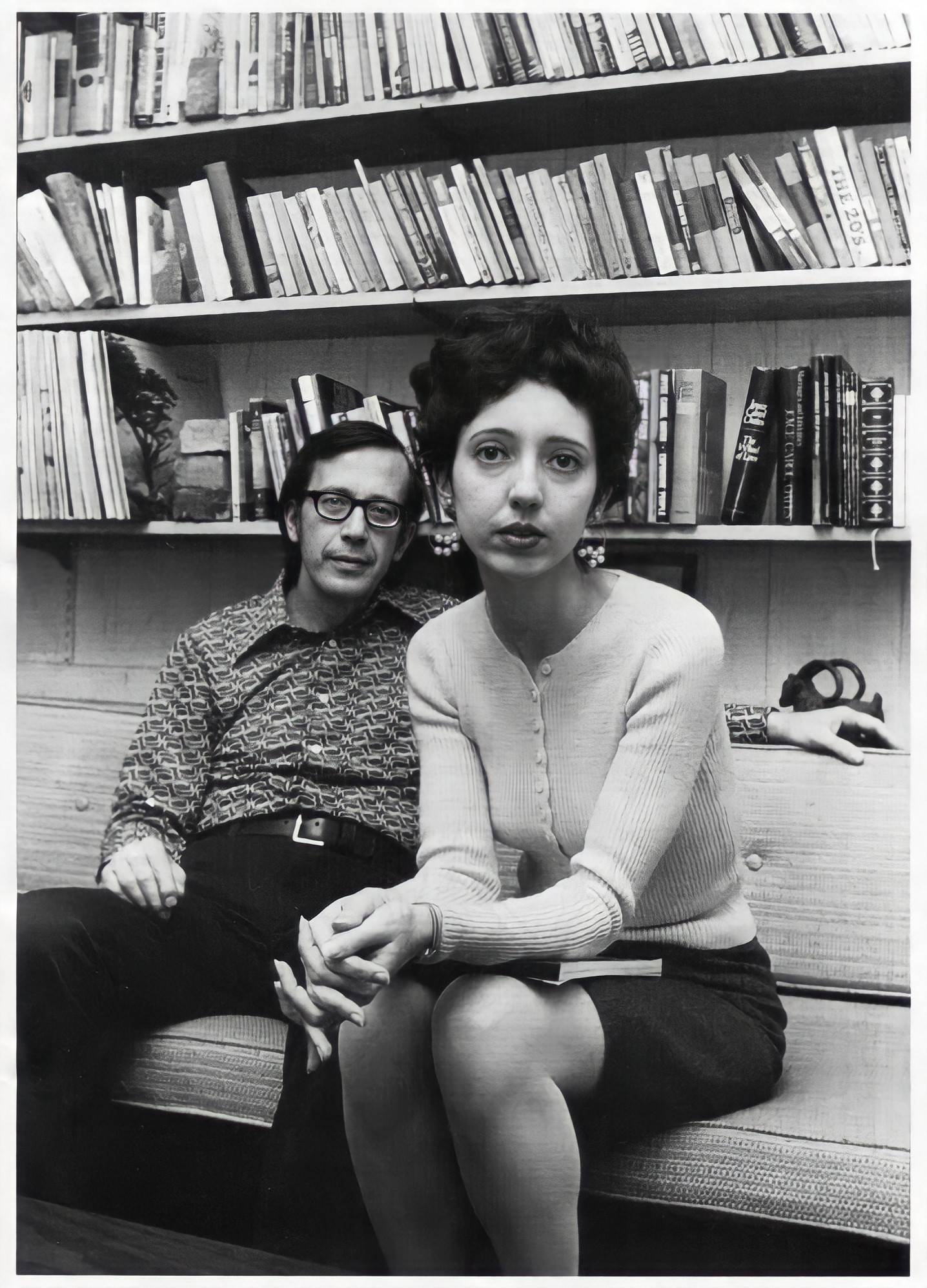

When she transferred to the high school in Lockport, she quickly distinguished herself. An excellent student, she contributed to her high school newspaper and won a scholarship to attend Syracuse University, where she majored in English. When she was only 19, she won the “college short story” contest sponsored by Mademoiselle magazine. Joyce Carol Oates was valedictorian of her graduating class. After receiving her bachelor’s degree, she earned her master’s in a single year at the University of Wisconsin. While studying in Wisconsin she met Raymond Smith. The two were married after a three-month courtship.

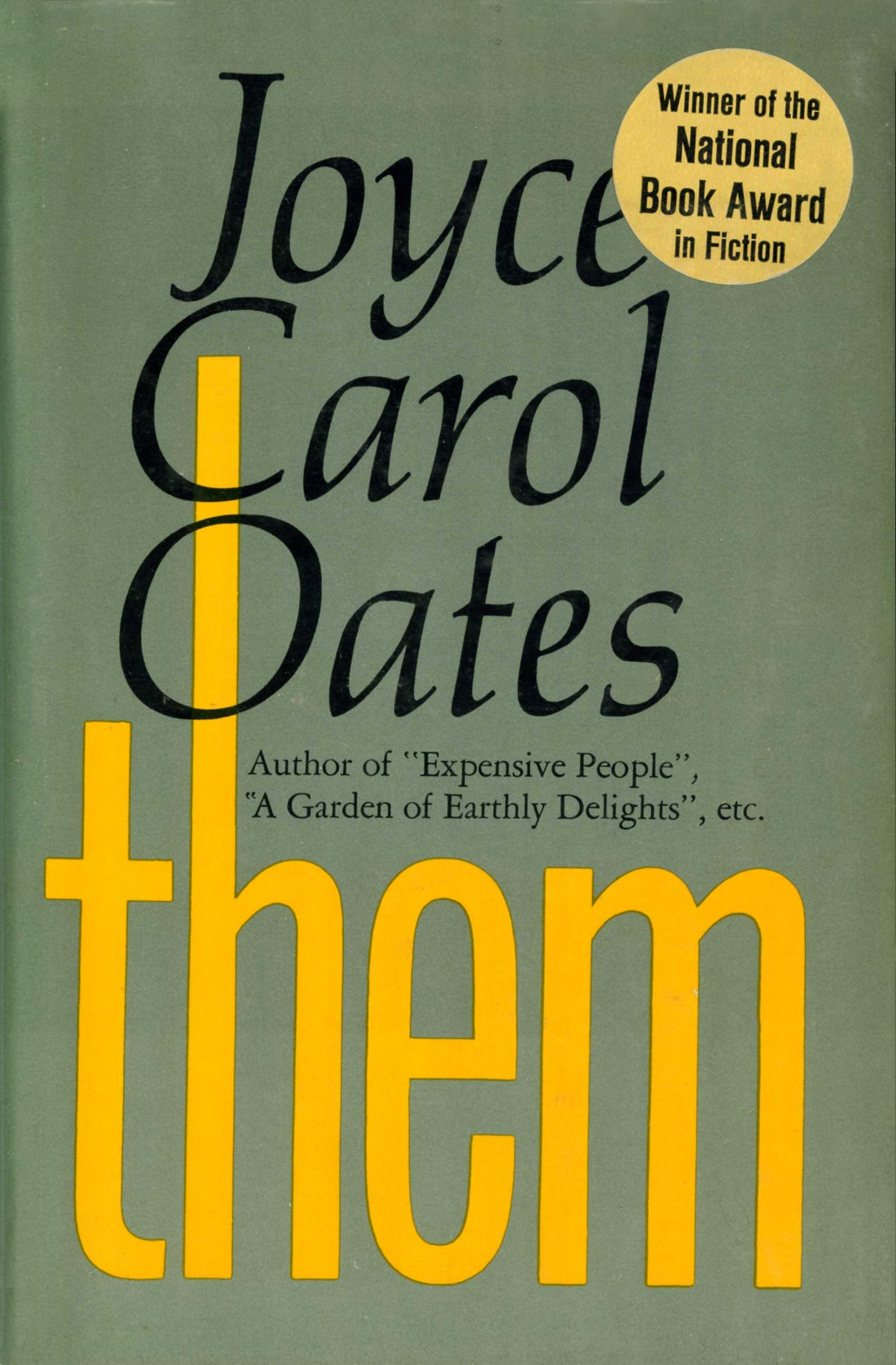

In 1962, the couple settled in Detroit, Michigan. Joyce taught at the University of Detroit and had a front-row seat for the social turmoil engulfing America’s cities in the 1960s. These violent realities informed much of her early fiction. Her first novel, With Shuddering Fall, was published when she was 28. Her novel them received the National Book Award.

In 1968, Joyce took a job at the University of Windsor, and the couple moved across the Detroit River to Windsor, in the Canadian province of Ontario. In the ten years that followed, Joyce Carol Oates published new books at the extraordinary rate of two or three per year, while teaching full-time. Many of her novels sold well; her short stories and critical essays solidified her reputation. Despite some critical grumbling about her phenomenal productivity, Oates had become one of the most respected and honored writers in the United States though only in her thirties.

While still in Canada, Oates and her husband started a small press and began to publish a literary magazine, The Ontario Review. They continued these activities after 1978, when they moved to Princeton, New Jersey. Since 1978, Joyce Carol Oates has taught in the creative writing program at Princeton University, where she has mentored numerous young writers, including Jonathan Safran Foer. Her literary work continued unabated.

In the early 1980s, Oates surprised critics and readers with a series of novels, beginning with Bellefleur, in which she reinvented the conventions of Gothic fiction, using them to re-imagine whole stretches of American history. Just as suddenly, she returned, at the end of the decade, to her familiar realistic ground with a series of ambitious family chronicles, including You Must Remember This, and Because It Is Bitter, and Because It Is My Heart. The novels Solstice and Marya: A Life also date from this period, and use the materials of her family and childhood to create moving studies of the female experience. In addition to her literary fiction, she has written a series of experimental suspense novels under the pseudonym Rosamond Smith.

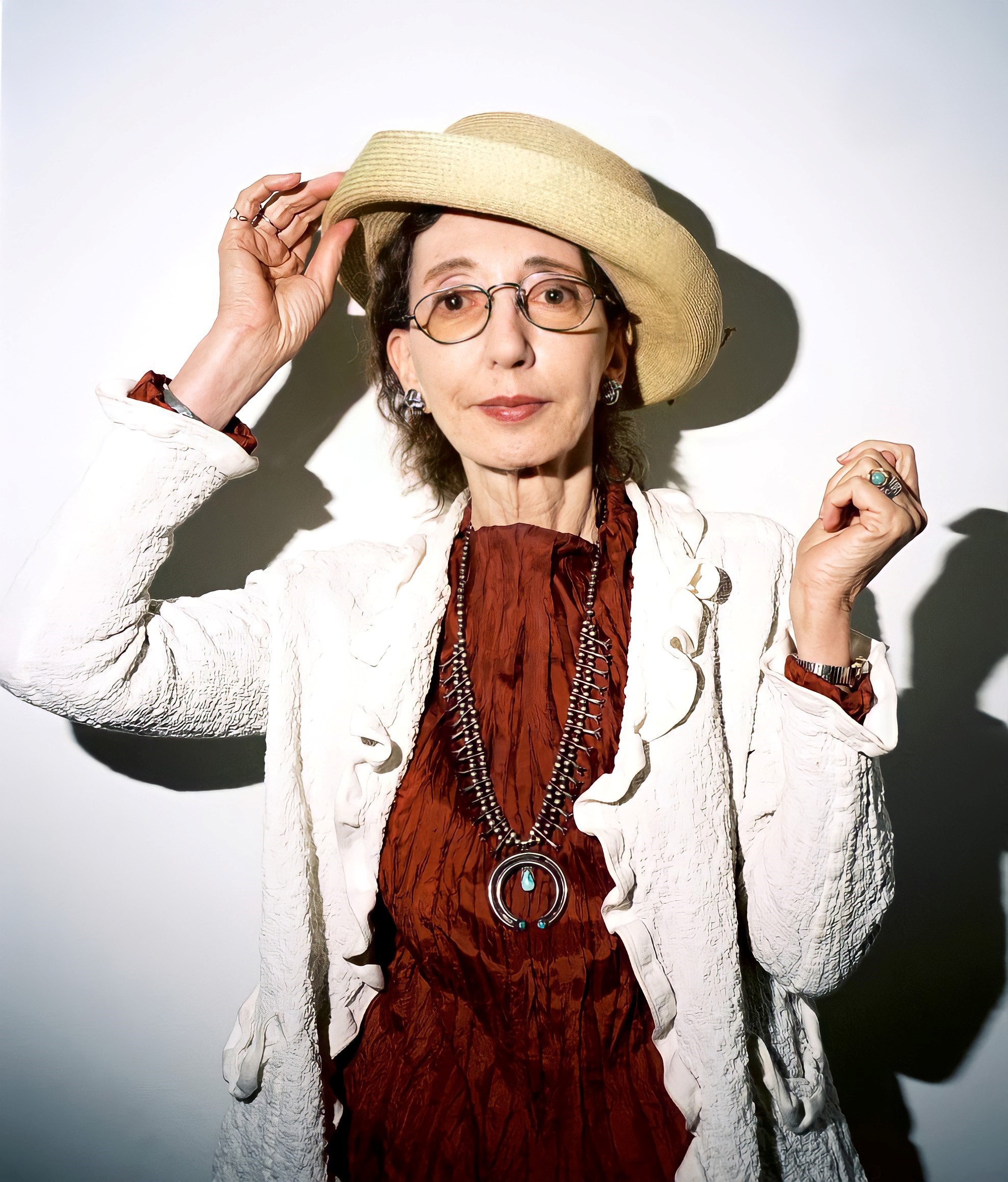

As of this writing, Joyce Carol Oates has written 56 novels, over 30 collections of short stories, eight volumes of poetry, plays, innumerable essays and book reviews, as well as longer nonfiction works on literary subjects ranging from the poetry of Emily Dickinson and the fiction of Dostoyevsky and James Joyce, to studies of the gothic and horror genres, and on such non-literary subjects as the painter George Bellows and the boxer Mike Tyson. In 1996, Oates received the PEN/Malamud Award for “a lifetime of literary achievement.”

Her husband, Raymond Smith, died in 2008, shortly before the publication of her 32nd collection of short stories, Dear Husband. The following year, Oates married Professor Charles Gross, of the Psychology Department and Neuroscience Institute at Princeton. In the months following Raymond Smith’s death, and before she met Dr. Gross, she suffered from severe depression and suicidal thoughts. She described this experience vividly in the memoir A Widow’s Tale, published in 2011. Today, Joyce Carol Oates continues to live and write in Princeton, New Jersey, where she is Distinguished Professor of Humanities at Princeton University.

Her most recent books include Babysitter — a novel about love and deceit, and lust and redemption, against a backdrop of shocking murders in the affluent suburbs of Detroit, The Accursed — an eerie and stunning tale of psychological horror — and the short-story collection, Lovely, Dark, Deep: Stories — a collection of ten mesmerizing stories that map the disturbing darkness within us all — which was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize.

“I come from people who did not go to college. They didn’t even finish high school. People who one might call ordinary Americans who are very hardworking.”

Growing up on a farm in the rundown North Country of Upstate New York seems an unlikely preparation for a literary career, but today, Joyce Carol Oates is one of America’s most prolific and respected authors. She has distinguished herself in the academic world as teacher and critic, while earning a fortune as the author of bestselling novels in a wide range of genres, from the family chronicle to the historical novel, the gothic horror story and the suspense novel, at the same time writing plays, verse and fiction of the highest literary quality. Her work has been distinguished from the beginning by a keen, unflinching interest in the nature of evil, and the sources of violence in American life.

She is the author of over 50 novels, winner of the National Book Award for the novel them and of the PEN/Malamud Award, given by the international writers’ association for “a lifetime of literary achievement.”

When was it that you first realized what you wanted to do?

Joyce Carol Oates: I began writing when I was very young. Even before I could write, I was emulating adult handwriting. So I began writing, in a sense, before I was able to write. But I didn’t think about being a writer. I think, like many children, I was just exploring different kinds of creativity, drawing and painting. I was making up little songs and singing and so forth. Writing happened to be something that I stayed with.

Did adults notice that you had this proclivity?

Joyce Carol Oates: Yes, I think they did. I was always encouraged. We were living on a small farm in upstate New York, and it wasn’t really an environment that was particularly receptive to children being creative. I went to a one-room schoolhouse. So I more or less just found my own way. But the adults in my family were very supportive and very warm.

What impact do you think your family and early environment had on your work?

Joyce Carol Oates: I’ve always been so interested in personal history. I’m very fascinated by my parents’ and my grandparents’ generations. I seem to think that they had a resilience and an integrity that may be somewhat deficient in my own generation, and in subsequent generations as well, because America has been rather easy to live in since the Depression. So, I’ve been so interested in my parents’ generation. And probably out of that respect — a curiosity for what they lived through — grew my fascination with subject matter.

What was the first thing you wanted to write about?

Joyce Carol Oates: The first things I ever wrote about were the animals and the farm. I love animals. I’m very close to animals, and I’ve lived with animals for quite a while. That goes back to childhood. I was writing about cats and writing about horses.

Was there a particular way that your parents encouraged you?

Joyce Carol Oates: My parents inspired me by their example. They both grew up in the Depression, and both of them had to quit school when they were quite young to work, because there actually was no choice. So, though they’re intelligent people — and my father in particular is interested in books and has subsequently, since his retirement, attended classes at the University of Buffalo — nonetheless, they didn’t have any opportunity to be educated. So they’ve always impressed me with their resilience, their good spirits, their courage. It wasn’t an easy life, and I won’t go into details, but there were a lot of problems. And yet they were never defeated. Somebody else might have been defeated. Someone else might have been really depressed, or become an alcoholic or something, because there were personal problems and economic crises. But I just remember them carrying on and just doing their lives. They really made a strong impression on me.

Apart from your very early attempts at writing and observation, what else in your youth prepared you for your career?

Joyce Carol Oates: My whole life. Much of what was absorbed unconsciously, in a kind of osmotic way, from the people around me, has led to the shaping of my writing.

I come from people who did not go to college. They didn’t even finish high school. People who one might call ordinary Americans who are very hardworking. Who were not self-conscious and were not thinking about themselves very much. I observed their lives. Some of their lives were quite difficult. There was a certain measure of violence in my world. I’m not from a middle-class world. I’m from another kind of world. And I absorbed things without being conscious of them. For instance, I was taken to boxing matches by my father when I was quite young, probably around ten years old. And so I inhabited, as a spectator, a very masculine world in which there were not very many women. I watched men fight, and boys fight, in a way that must have seemed to me paradigmatic of the world, though I didn’t have that vocabulary. I didn’t have a feminist position, and I wasn’t saying, “Well, this is brutal and this is ugly and this is cruel.” I was just looking at it with open eyes and thinking, “This is the way the world is.” This has all been internalized. I see the world in ways that might be considered somewhat harsh and Darwinistic. At the same time mediated, as in Darwin, by a real idealism and an excitement about the possibilities of the intellect and imagination to deal with this somewhat brutal world.

Did you have any major setbacks while you were creating yourself as a writer?

Joyce Carol Oates: Major setbacks?

I have minor setbacks probably every day of my life. I have a friend in Princeton, who’s a writer named John McPhee. He says every writer has a mini-nervous breakdown sometime in the mid-morning but keeps going. I guess that’s about it. Each day is like an enormous rock that I’m trying to push up this hill. I get it up a fair distance, it rolls back a little bit, and I keep pushing it, hoping I’ll get it to the top of the hill and that it will go on its own momentum. I’m very deeply inculcated with a sense of failure for some reason. And I’m drawn to failure. I often write about it, and I’m sympathetic with it, I think, because I feel I’m contending with it constantly in my own life. A sense that there is a movement toward light or illumination which requires strength and ingenuity. But then there’s another contrary force that pulls us back into defeat and a sense of giving up. I feel, probably, that I’m in the throes of that contest every day of my life, virtually.

Was there ever a day when you felt like giving up?

Joyce Carol Oates: I’ve felt like giving up many times. It’s hard to talk about now, because one cannot convey the depth of the emotion. When one talks about something retrospectively, it seems to be under control, but during the experience, there was no sense of control.

What kept you going when you felt like a failure?

Joyce Carol Oates: I’ve never given up. I’ve always kept going. I don’t feel that I could afford to give up. That would be the beginning of the end. There was one project I was working on once. I was doing a book on boxing with a photographer. And I was very fascinated by the material. And I wanted to write the book very, very badly. So I was in a state of anxiety and tension about writing it. And it seemed that I could not even begin it. And I tried and tried for days to get a way into this book. And I had different openings. And I simply couldn’t do it. And so I finally felt that I’d given up. And I was very disintegrating and very depressed. I thought it was the beginning of the end, that I would never be able to do anything again. So I went to bed, and all night long I was thinking about these distressing thoughts. And towards the morning, I started thinking, “Well, failure is actually what most people experience in boxing.” Most athletes inhabit failure, but particularly boxers. And they’re punished — extremely punished — for instance, for failure, or a little bit of carelessness. So I started writing about a boxing match I had seen in which somebody failed ignominiously, and the crowd in Madison Square Garden was vicious. And I thought, “There. I can identify with those two boxers.” And I found a way to write about the whole sport by way of beginning with failure, with the image of failure.

That’s the most powerful example in my memory of how I had given up. But then, by way of connecting with subject, with theme, I was able to find a kind of lifeline. Writing’s like a lifeline. You have to get the right way in. Otherwise the material just lies there, and you can’t do anything with it.

What did that project turn into?

Joyce Carol Oates: It turned into a book called On Boxing with photographs by John Reiner. It’s gone through a number of editions. It’s been translated and published in many countries and was recently updated with some pieces about Mike Tyson, who is the only boxer whom I really got to know.

You’ve enjoyed great success as a writer. Have you ever turned down an opportunity because you felt it just wasn’t right for you?

Joyce Carol Oates: I’ve turned down opportunities constantly. I turn down invitations to do things for money. I have almost no interest in making money. Actually, I’ve acquired a fair amount of money that I will never live to spend. It’s been earmarked for various charities and worthwhile places. So earning money, in a way, depresses me, because I feel it’s just piling up. And there’s just something melancholy about the image of money piling up that will never be drawn upon. I think what distresses me most in my life is that I have so many ideas I consider exciting ideas that I will never live to execute because it takes me so long to execute.

When did you first conceive of a life as a writer?

Joyce Carol Oates: I never conceive of my life as a writer. I think that in the arts, people like to do what they’re doing. People play piano because they love it. Or they’re working with paints, or they’re sculpting. But when one crosses over from an activity, or the verb, of writing or doing, and becomes a noun, like “a writer” I think that is an act of supreme self-consciousness that I’ve never, in effect, made. I write, but I don’t like to think of myself as a writer. I think it’s somewhat self-aggrandizing and pretentious. Now, I am a teacher. Literally, I am a teacher. That’s a different kind of activity. But to be a writer is something I would rather just do, instead of talking about being.

What drew you towards teaching?

Joyce Carol Oates: I always wanted to be a teacher. I admired my teachers in elementary school. I thought it would be a good life, and my parents were very supportive. I got my BA degree from Syracuse University, where I had wonderful teachers. Then I went to the University of Wisconsin to get a master’s degree. I wasn’t so interested in the teaching there or so impressed by it. It was much more scholarly and erudite and somewhat dry. But I got my master’s degree in one year, and I didn’t do any teaching.

I had a fellowship, and I got a job to teach at college level. I had four courses at the University of Detroit. I had never taught before and was amazed that I had been hired to teach four courses without having taught before. That was very nice of these people to hire me. I came into the classroom, and there were about 40 students. It was a night class. And I had been very excited and really frightened because I had never taught before. And I remember walking in the room, and I came to the podium, and I looked out and some of these students were older than I was — I was only about 22. Such a feeling of happiness came over me. I thought, “This is where I belong.” Then I started teaching, and I just loved it. I can’t imagine where I got that confidence. If I had been very nervous, I would have been quite comprehensible. What seems surprising to me was that I wasn’t really nervous, and that I loved it. And I felt so happy. So I always feel very happy teaching. A wave of happiness comes over me in the classroom.