Respect is a lot more important, and a lot greater, than popularity.

Julius Erving was born in Hempstead, Long Island. His father left the family when Julius was only three. His mother worked as a domestic to support her three children. The family lived in a public housing project, and life was difficult, but Mrs. Erving worked to instill a sense of self-worth in her children, and young Julius realized his gift for basketball could be a ticket to a better life. By age ten, Julius was averaging eleven points a game with his Salvation Army team. When Julius Erving was 13, his mother remarried, and the family moved to the nearby town of Roosevelt. There, Julius maintained a high academic average and played on the high school team, all-county and all-Long Island teams competing in statewide tournaments. Erving acquired the nickname “the Doctor” while still at Roosevelt High. His teammates would later alter this to “Dr. J.” The basketball coach at Roosevelt High, Ray Wilson, introduced young Julius to Coach Jack Leaman of the University of Massachusetts. After high school, Erving entered the university, where Ray Wilson was hired as assistant coach the following year. At Massachusetts, Erving broke freshman records for scoring and rebounding, leading his team through an undefeated season. The next year, he had the second best rebound tally in the country. Over the summer, he joined an NCAA all-star team touring Western Europe and the Soviet Union. He was voted Most Valuable Player on this tour. Julius Erving left the university to go professional after his junior year. He is one of only five players in the history of NCAA basketball to average over 20 points and 20 rebounds per game.

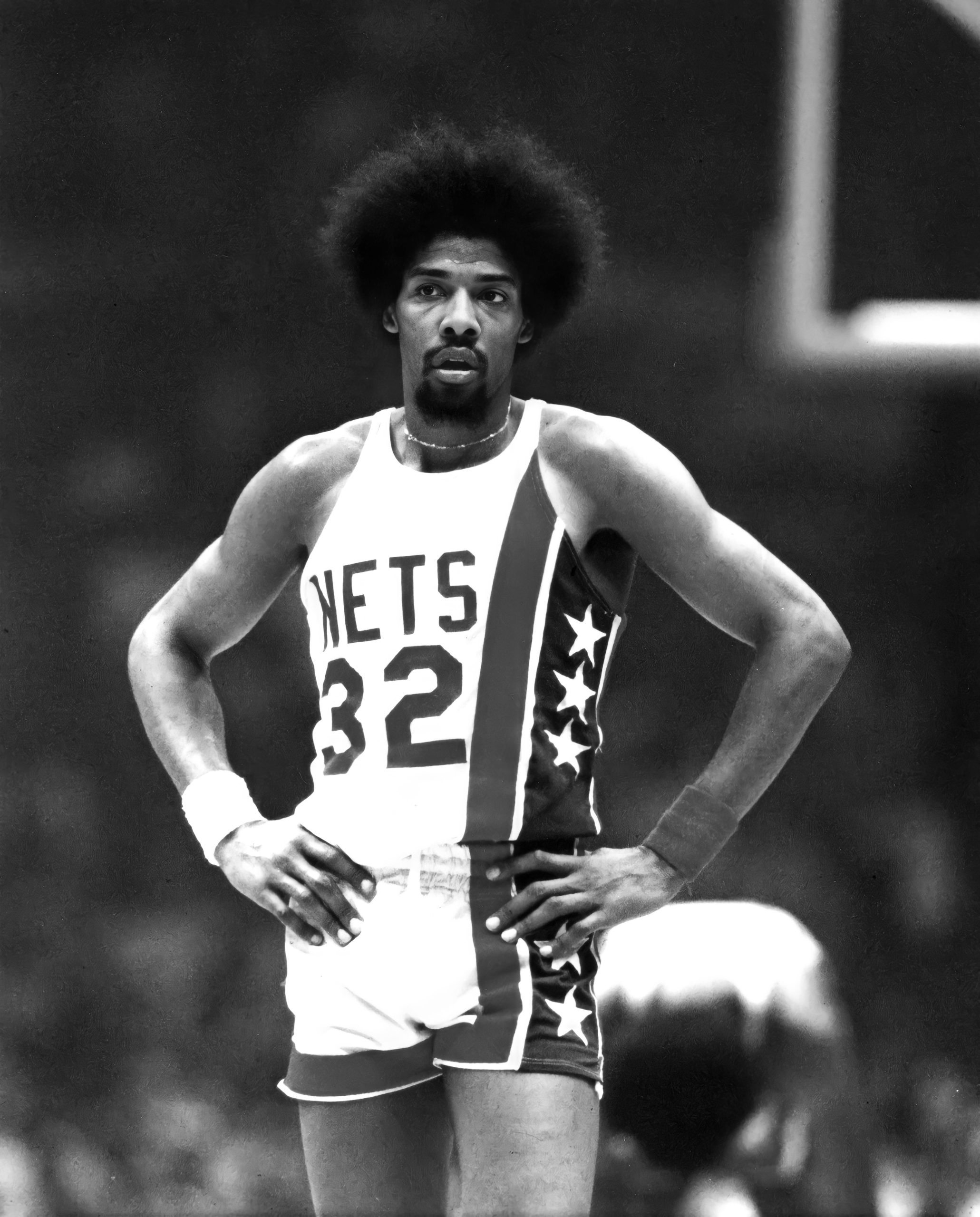

In 1971, Julius Erving began his professional career with the Virginia Squires of the American Basketball Association. The ABA was fighting an uphill battle to gain the same recognition enjoyed by the more established National Basketball Association (NBA). Julius Erving, or Dr. J, as fans now called him, did more than anyone else to win that recognition for the new association. In his first pro season, Dr. J ranked sixth in the ABA in scoring, third in rebounding.

The following year, he led the ABA in scoring, averaging 31.9 points per game. In 1973, Dr. J attempted to sign with the Atlantic Hawks of the NBA, and found himself in the middle of a complicated legal wrangle. The Squires claimed he was still under contract to them, the Milwaukee Bucks claimed draft rights to Erving under NBA rules, and his old management sued him for damaging their reputation by trying to break the Squires contract. The affair was finally settled out of court. Erving remained with the ABA to play for the New York Nets. Once again, Erving led the league in scoring and led the Nets to an ABA championship, winning four-out-of-four games against the Utah Stars. In the first of these games, Erving scored 47 points, sparking comparisons with the greatest players of all time.

In the 1974 season, Erving suffered from knee pain and was forced to wear special braces on the court, but it didn’t stop him from another spectacular season. On his 25th birthday, he scored 57 points against San Diego.

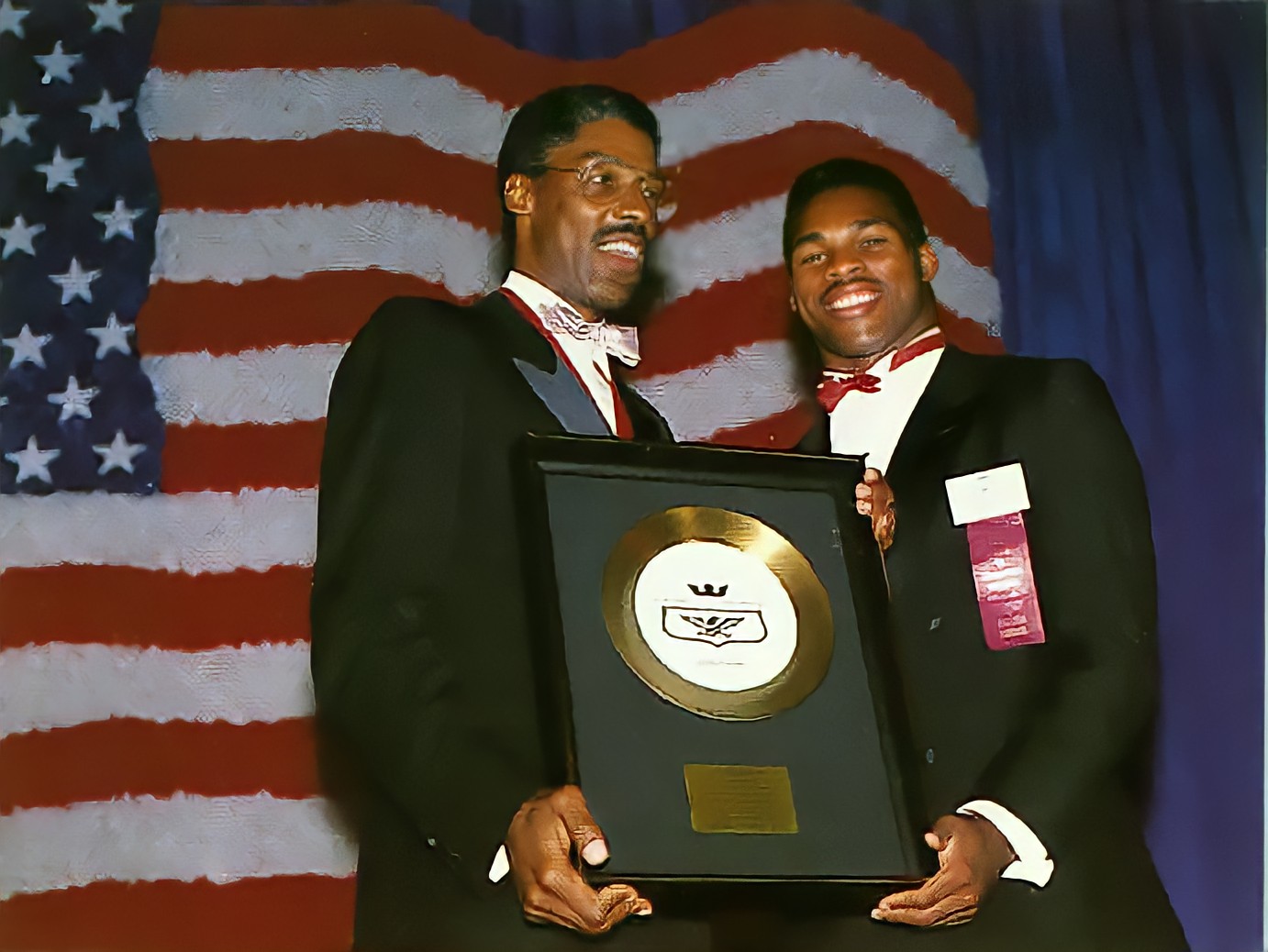

After being voted Most Valuable Player in the ABA from 1974 to 1976, Dr. J moved to the Philadelphia 76ers of the National Basketball Association. He remained in Philadelphia for the last 11 years of his pro basketball career, leading the 76ers to an NBA championship in 1983. When Dr. J finally retired in 1987, he had scored over 30,000 points in his professional career; he is one of only three players in the history of the game to achieve this feat.

After retiring from professional basketball, Julius Erving became a commentator for NBC and appeared in the feature film The Fish That Saved Pittsburgh. Julius Erving was one of the original athlete-businessman, his first contract with Converse was worth a then-unprecedented $20,000.

He also endorsed the first licensed video game “Dr. J vs. Larry Bird,” which was released by Electronic Arts in 1983. As part of his endorsement deal, Erving received the option to purchase 20,000 shares of the company at $1 a share. He held onto the shares which was eventually worth millions of dollars. Erving was also an investor in the Philadelphia Coca-Cola Bottling Company for more than two decades. In 2016, Erving sold the majority rights to his name and image to the Authentic Brands Group.

As part of the contract, ABG has filed for the trademark to “Dr. J” as well as Erving’s signature in the United States and around the world. Julius Erving now resides in Atlanta with his second wife, Dorys. He is, of course, enshrined in the Basketball Hall of Fame, and in the memories of everyone who ever saw him play.

“I saw that basketball could be my way out and I worked hard to make sure it was.”

The boy who became “Dr. J” began life in a public housing project, but his talent, hard work and determination were to take him a long way. One of the most exciting and talented players in the history of professional basketball, Julius Erving literally changed how the game is played. He is one of only three players in history to score a career total of over 30,000 points in professional play.

In the 1970s, Julius Erving did more than anyone to build the fledgling American Basketball Association (ABA) into a worthy rival of the NBA. He was voted Most Valuable Player in the ABA for three consecutive seasons. When he moved to the Philadelphia 76ers of the NBA, he continued to surprise and delight the fans with his dazzling moves. And all lovers of the game, Philadelphia fans in particular, thrilled to see Dr. J leap from behind the foul line, traveling 15 feet through the air to dunk the ball, throwing off the opposition with multiple mid-air feints along the way.

His unique and imaginative style of play has forever changed our notions of what is possible on a basketball court. In a sense, today’s basketball superstars are all the children of Dr. J.

You certainly had glorious years, college and pro, and I wanted to touch on some of those highlights. When you look back, what are some of the most thrilling moments for you?

Julius Erving: I always try to keep a pretty conservative demeanor on the court. I was characteristically unfazed by a lot of things that happened around me. That was just my own personal program: I didn’t want to get too high over the good moments because I didn’t want to be saddened and depressed when things didn’t go as I had planned. From experiencing both sides of the fence, that became my public demeanor.

The first professional game that I ever played remains, to me, the most exciting moment of my professional career. I had signed a contract with the American Basketball Association, and we had gone through an exhibition season. A lot of speculation had been created about me, and my teammates, and my team, and what our talents were, and that we were an exciting team to watch. We represented something new and exciting in the game of professional basketball because we played at a fast pace. We always pushed the ball, and there was a lot of room for creativity and excitement. Our game was a lot different than what was being played in the NBA. We featured a lot of slam-dunking.

The first professional game was clearly different from the exhibitions and what had happened in the summer. Even though I had been on the basketball court with a lot of professionals, this is when it really counted. This was the beginning of the career.

I remember my first college game as a varsity player. I had a 27 point/28 rebound game. I wasn’t a big guy, but I was able to chase rebounds down, and that set a school record in the first game.

I wanted to make a good impression. I knew that rebounding was the strongest part of my game and I said, every shot I take tonight I might miss, because sometimes that happens. I didn’t think that was going to happen, but I knew that that was a possibility. And that was something that if it did happen, I would have to live with it. So, I started trying to think of things that I definitely had control over. And I said, when that ball goes up on the board, nobody is going to pursue it harder than I. And with my jumping ability, and quickness, I know I can out-rebound everybody on the floor.

I grabbed 19 rebounds in my first professional game, and somehow found a way to score 20 points. I felt real good about it. I felt that this was the beginning of something good. It was something that I had dreamed about as a kid, something that I didn’t think was promised me, and I was never sure that it would happen. Yet it was happening, yet I was here, and yet it was reality, and now it was time to see what I was made of, and what I was about. It became a real good experience. All the things that followed after, in 16 years of playing: the play-offs, and the excitement of championship play, and the frustration of getting knocked out, and the frustration of injuries, and pain, and becoming close to teammates and then they get traded. The transition from playing with three different teams during 16 years, all those things. I don’t think any of those things excited me as much as the first game. Because, once again, I kind of programmed myself: “This is a business.”

My role models in the business were the older guys on my team when I first got there: Gray Scott, Adrian Smith, Roland Taylor. These were the guys who took me under their wing, and really schooled me in terms of what the business was about.

I always had to keep in mind that I’m here because I do have a talent, and some aspects of it are unique. I should keep that in my mind, not feel that I’m here because people just like me, and because I’m a nice guy. Sometimes I will be treated differently by a lot of people because of that talent, but don’t let that become a distraction, and don’t be deceived by that. See it for what it is, and then play the hand out. So much of becoming a good athlete involves bringing other things to the table, other than physical skills. It involves intelligence, it involves many of the things that you learn during the process of being educated. How to analyze, how to assess, how to equate, how to reason. This is what the whole elementary, and secondary, and even the college educational process is all about — teaching you and preparing you to be able to deal with what you ultimately have to deal with in life. Even though I was dealing with sports, which many people feel is totally physical, that people don’t have to think, everything is done for you and you’re catered to, I found that to be so far removed from the truth that it’s almost a joke. The ones who become stars or superstars are the ones who have a head on their shoulders and know how to use it.

You mentioned the skills, other than just sheer physical skills, that go into sports. One that comes to mind in your case is leadership. You’ve always been described as a leader. What do you think people see in you that causes them to say that?

Julius Erving: I think people see commitment. Every team that I’ve played on, I’ve either been the captain or co-captain. Whether it’s the coach’s appointment, or the players’ vote, it’s generally turned out that way. So there are a lot of athletes who have always been willing to follow my lead.

I think as a youngster the work ethic was there, practicing hard and being dedicated and not, by nature, being a complainer. My teammates have always related to me in that way. I think probably the best compliment I’ve ever received from a teammate was what Henry Bibby told me after we had played together for two seasons in Philadelphia. He said, “Of all the guys that I’ve ever played with, I don’t know if you’re the best that I’ve ever played with, but I know you come to play every night. And because of that, I feel like we always have a chance of winning.” I thought it was a great compliment.

I thought about that in terms of the other aspects of my life where I need to display leadership. Sometimes I have been reluctant, because I don’t think it should be assumed that because you’re a leader in one area that you can lead in all areas. Some areas maybe you’re better off following, or at least listening, and getting your feet wet, and letting it be a process of time. But in sports, for the most part, I’ve been given that responsibility, and accepted it willingly, and gladly, and thought that it fit.

Your career was tremendously impressive, and it seemed to happen all at once. But there were, I’m sure, disappointments along the way. Early years in Philadelphia were a little disappointing, I understand. How do you get yourself back on track, when you’ve had setbacks?

Julius Erving: There were periods in my life when I would just internalize it, and then I decided that that’s not the way to go. I had to go through trial and error. I’ve never been depressed in my life, that I recall. Being a typical Pisces, I might have experienced mood shifts, but I don’t remember any depression, or needing to do anything, or to have someone bring me out of being depressed.

Everything is relative. I started playing professional basketball in 1971, and I played professionally for five seasons before going to Philadelphia. During those five seasons, a lot of what transpired was done in the obscurity of the American Basketball Association, which didn’t have a major television contract. They didn’t have the exposure of the NBA. There was a lot of success there, particularly when I played with the New York Nets, and we won the ABA Championship two different years. That created a lot of expectation when I went to Philadelphia.

When I went to Philadelphia I was 26 years old and really sitting on top of the world. Family life, a professional career, plenty of friends and associates, and a good reputation, a wish list that could be the envy of many.

In Philadelphia, our team was put together and I became the last component of that team. It was sort of parallel to what happened with the Yankees: George Steinbrenner getting all these players together and winning the World Series. There were a lot of assumptions that, in basketball, that’s how things worked: if you put together a lot of high-priced talent, they were going to win.

The first year that we were together, we were the second-best team in the world. We went to the finals and we lost in six games. We won the first two, and we lost the next four. The team suddenly became stigmatized. It was like, those guys are good, but they’re not winners.

If you get depressed about being the second-best team in the world, then you’ve got a problem. I tried to take a leadership position, and kind of explain that to my teammates and whoever would hear me. I found myself suddenly becoming defensive about something I really didn’t think I should be defensive about.

There were, at that time, 23 teams in the league. We were better than 21 of them. There was one that was better than us, and maybe we’d have another shot at that team. As it turned out, we never got another shot at them; they never got back to the championship round. We went back three other times and the third time after that, won the championship.

There was a sense of relief from doing that. I don’t think there ever was a time in which I got depressed over not having it. I think there were times in which I publicly acknowledged that there was a void created because of not having it. But a void is far from depression. A void is something that you can live with in your life, provided there are enough other things to compensate for things that you don’t have.

I tell people, young people and old, “Be careful what you wish for, because you might get it.” I think it’s best advised to wish for things that are within your control to attain. Although that was something I wanted, I probably could have lived without it. Right now, I’m not sure how much of a difference it makes in my life, on a day-to-day basis.

I firmly believe that respect is a lot more important, and a lot greater, than popularity. When you become a world champion, you’re not automatically respected. You’re immensely popular because of that, because of the media coverage and exposure, but respect is something that you garner by going through the long hard route of giving it, and receiving it, and making it solid, and it’s a permanent situation. To have the respect of a lot of people and to be a respected person is so much more important to me at this stage in my life. If I had not won a world championship in basketball, I think that that would probably still be there. That’s really what counts to me.

You’ve described the thrill of the roar of the crowd, the chemistry that you feel when you’re on the court and it’s happening. What does that feel like?

Julius Erving: When the crowd appreciates you, it encourages you to be a little more daring, I think. That’s probably what the home court advantage is all about. With the crowds on your side, it’s easier for you to get ready to play and to get to the point where you’re playing up to your potential. Generally, you’ll have more players on the home team playing up to their potential than on the road team. Because in all professions, talented people sometimes react adversely to being booed, or jeered, or going into a foreign arena. It takes them a little longer to get focused and to reach their full potential, and to get into stride, get into sync. You’ll find some teams that are good home teams that are lousy road teams because of that. The perception is that the home team will always have an advantage. When you find a team that’s a great team on the road, they’re generally listed as a championship caliber team, because they’ve been able to overcome this. This is simply one of the psychological aspects of the game. There’s physical, there’s mental, and then there’s a psychic side to sports, which a lot of people write about, and very few people study. I don’t think I began to study it until I was in my late 20s. The last eight or nine years of my career I spent more time in learning about the psychic side of sports, because that’s where there was a greater learning curve available for me, versus trying to physically jump higher, or shoot straighter, or run faster, because that wasn’t really going to happen. But the psychic side opened doors for me, opened passages for me, physically and mentally, and allowed me to become a better player at an older age. At age 31, in 1981, I was voted the best player in basketball, and the most valuable player in the league. That’s considered old. You have a lot of guys who start out at 20 now, and this was after playing for ten years. I thought that was something that I needed to credit — understanding better the psychic side of the sport, versus physically going out and doing anything any differently.

You mentioned daring, and that’s another hallmark of your career: flamboyance and incredible moves. You’re a great showman, and I wonder how much of that is spontaneous and how much of it is deliberate. Is it in response to the crowd? It’s a very creative approach to basketball.

Julius Erving: I think it was in response to the crowd, because the crowd reacts after you do a good move. The crowd’s response might help set the stage for something that happened later. Oddly enough, my particular style of play was really rooted in the fundamental approach to playing the game, with one exception.

When handling the ball, I always would look for daylight, wherever there was daylight. Sometimes there’s only a little bit of daylight between two players, and you’d find a way to get the ball between those two bodies and you make something happen. Having good peripheral vision, I would always see daylight. Maybe I could see daylight that a lot of other players couldn’t see. I see a lot of extraordinary players today, Jordan and Drexler and what have you. They see daylight where other players don’t see that daylight. They see a body there, and they don’t want to challenge that body, and they just don’t see the daylight. So, that’s a great optic option to have. The flamboyance wasn’t intentional. The approach was result-oriented, more than reaction-oriented. Trying to get the results — stop the team on defense anyway you can: block a shot, steal a ball, force a turnover. Offensively: try to score, set up a teammate to score, keep it very simple. The result was the priority, the effect was an added bonus, I guess. That was part of the gift, the blessing. Once it became very sensible business-wise, if you do things with a certain type of result and cause a certain type of reaction or effect, then you increase your market value. It’s very much a competition for the entertainment dollar, and that’s never been more clearly evident than in today’s NBA game.

What is the future of the NBA?

Julius Erving: I think the game will be an international sport, very much in the same vein as soccer. It’s probably only a close second to soccer now, and a lot more popular than soccer in a lot of markets where soccer isn’t even played. This will continue to grow. The league is committed to this. I think the basketball world is committed to it. I play a role in that now, in terms of the international aspect of the game.

Where did the nickname Dr. J come from?

Julius Erving: In high school I had a buddy who I called the Professor, and he called me the Doctor. His name is Leon Saunders. We went to high school together, and then we went to college together, and we’re still great friends today. I used to call him the Professor because, when we would do anything, whether it was playing basketball, or cards, or just sitting around and shooting the breeze, he always had to have the upper hand. He could outtalk anybody, to the point where he would lecture whoever else was around, if we were willing to listen. I just kind of dubbed him the Professor one day. And he said, “Well, if I’m the Professor, then you’re the Doctor.” We kind of had professional-sounding nicknames, and we just shared that amongst ourselves. Then we ended up graduating high school together, going to college, and other people picked up on our nicknames. Mine eventually got changed to Dr. J, instead of just the Doctor, once I started playing professional basketball. The team physician was called Doc, and the trainer was called Chop. But the physician became Dr. M, and I become Dr. J, compliments of a guy I was rooming with in my first year, a guy named Willie Soldier. Dr. J was kind of catchy, and I liked that. I said, if I’m going to go through a name change, that’s not a bad move. It just sort of stuck since then, and it’s still here.