When is the best time to start doing the actual writing, the writing of the words that go into the book? You’re just improvising. But you can get some kind of strange force out of that serendipity and improvisation, and you can bypass your own senses in a way and surprise and even shock yourself.

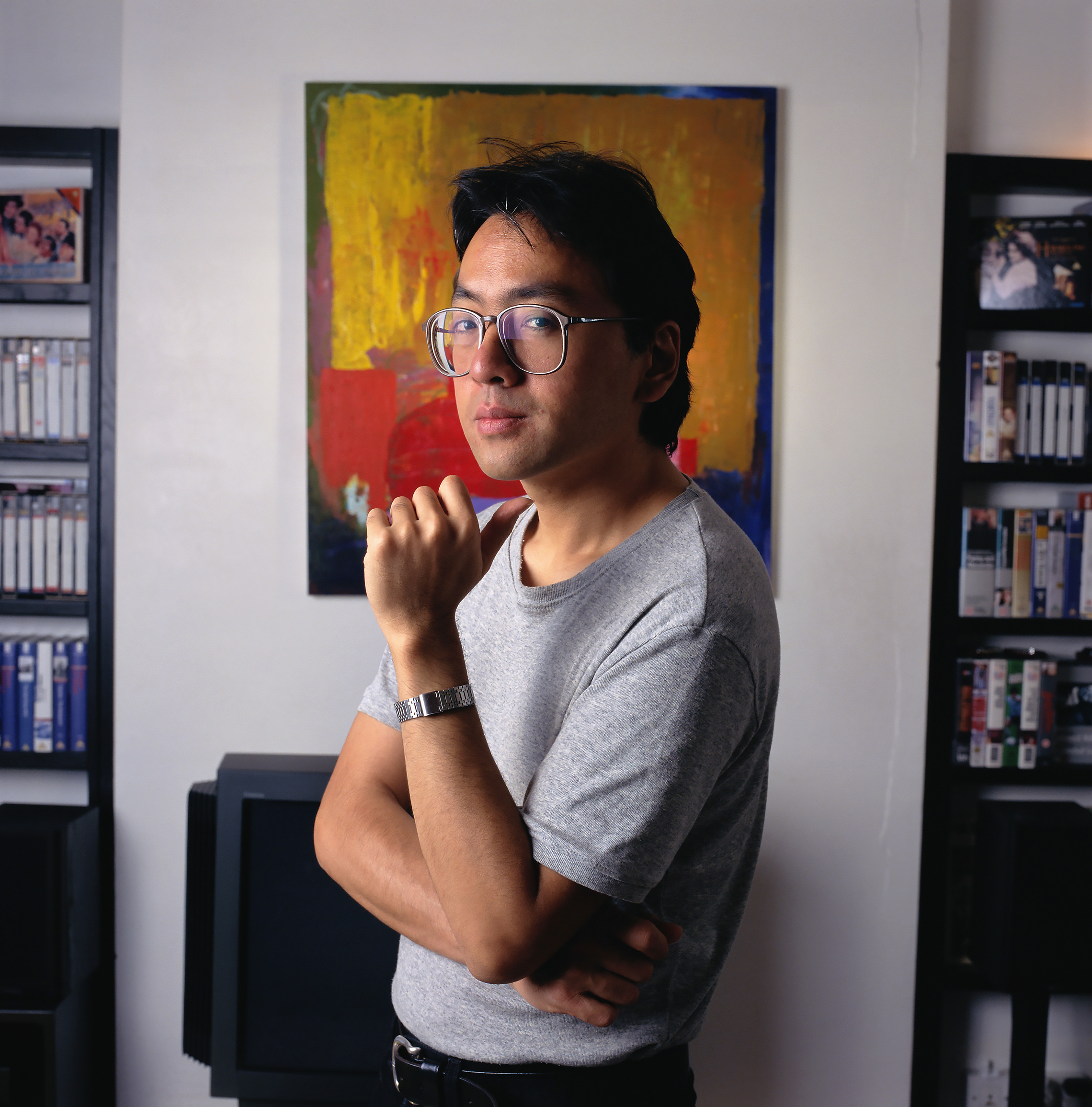

Kazuo Ishiguro was born in Nagasaki, Japan. His mother had survived the atomic bomb attack on the city that ended World War II; his father had spent the war years in Shanghai. When Kazuo was five years old, his father, an oceanographer, accepted an invitation from the British government to conduct research in England, what he thought at the time was a temporary assignment in England. The family moved to Guildford, in the south of England. The temporary assignment became a permanent position, and though the Ishiguros continued to speak Japanese at home, young Kazuo grew up in an English town, attending English schools and singing in the church choir. When he was 15, his family decided to remain in Britain permanently. He did not see the country of his birth again until his mid-30s.

As a boy, Kazuo Ishiguro enjoyed television Westerns and spy stories and wrote easily without entertaining any serious ambition of becoming a writer. The great creative awakening of his adolescence came at age 13 when he discovered the songs of Bob Dylan. He spent the next years learning to play guitar, writing songs, and studying the work of Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell and other singer-songwriters of the era. After graduating from Woking Grammar School in Surrey, he took a year off to travel in the United States and Canada, and to make the round of record companies with demos of his songs.

Although he still planned a career in music, Ishiguro studied literature and philosophy at the University of Kent in Canterbury. He began to read more seriously in college, taking a special interest in the novels of Charlotte Brontë and Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Of contemporary novelists, he remembers enjoying the work of Margaret Drabble.

On graduating, he moved to London, still hoping to pursue his songwriting career. He supported himself by working at a homeless shelter in Notting Hill, operated by the Cyrenians charitable organization. He played his music in bars and coffee houses and made the rounds of agents and record labels with demo tapes, but a recording contract eluded him. Meanwhile, at the homeless shelter, he was getting a second education — in the hardships of life and the mysteries of human character. While working at the shelter, he also met a young social worker named Lorna McDougall. They fell in love and in time would plan a life together.

Thwarted in his music career, and uncertain of his future direction, he wrote a short radio play called Potatoes and Lovers and submitted it to the BBC. The script was not accepted, but the readers at the BBC saw potential in his work and encouraged him to pursue writing further.

An advertisement drew his attention to the master’s program in creative writing at the University of East Anglia. Graduate writing programs were a novelty in Britain at the time — a previous year’s course had been canceled for lack of applicants — but Ishiguro was intrigued that one of his favorite contemporary authors, Ian McEwan, had studied there. Ishiguro submitted his radio play as a writing sample, and to his surprise, was accepted into the program.

He now became nervous that he was unprepared for the course, so he spent the summer of 1979 in a rented cottage in a remote area of Cornwall, reading, writing, and studying the short story form. With two stories completed, he felt more confident in entering the program. His tutors, Malcolm Bradbury and Angela Carter, were encouraging, but his efforts to write about the life he knew in Guildford and London fell flat. Recalling his mother’s stories of her youth in Nagasaki, he set a story there, describing the atomic bombing of Nagasaki from the point of view of a young woman. The necessity of describing a city and era he had not experienced stimulated his imagination. His fellow students were excited by the results. With a new energy in his writing, he reworked one of his earlier story ideas, setting it partly in Japan, and as the story grew beyond the limits of a short story, he made it his master’s thesis.

Before he graduated from the program, three of his stories were accepted for Introductions 7, an anthology of young British authors published by the historic publishing firm of Faber and Faber. Robert McCrum — an editor at Faber only a few years older than Ishiguro — took an interest in his work. McCrum offered Ishiguro a £1,000 advance to expand his master’s thesis story into a full-length novel. Ishiguro completed his course at East Anglia and returned to London and his old job at the homeless shelter while completing his first book.

Ishiguro’s first novel, A Pale View of Hills, was published in 1982 when he was 27. In its pages, a Japanese woman living in England recalls her earlier life in Japan, while trying to come to terms with a daughter’s suicide. The memories of Japan are interwoven with observations of life in England “through Japanese eyes.” Ishiguro’s first novel won the Winifred Holtby Memorial Prize from the Royal Society of Literature, awarded specifically for its depiction of an English setting. The following year, he was chosen alongside Martin Amis, Julian Barnes, William Boyd, Salman Rushdie and his East Anglia predecessor Ian McEwan for the literary journal Granta’s list of the best young British novelists. Having become a recognized British author, he knew his future lay in Britain, and he became a British citizen as well.

Ishiguro and McDougall married in 1986, the year he published his second novel, An Artist of the Floating World. Set in Japan in the years following World War II, its narrator is a painter and printmaker struggling to live with the consequences of his support for the pre-war militarist government. The novel is driven in part by the tension between the reader’s judgment of the narrator’s actions and his effort to justify himself. This second novel won the Whitbread Book Award (now known as the Costa Book Award) and was shortlisted for the even more prestigious Booker Prize.

Having won praise for his two novels set in Japan, Ishiguro decided to write a novel set firmly in the country where he had spent almost all of his life. In reading the history of 20th-century England, he became fascinated by the life of the pre-war aristocracy and their servants, and particularly by the set of extremely conservative nobles, some of them sympathetic to Nazi Germany, who opposed Britain’s entry into World War II. He read numerous memoirs of the period, steeping himself in the milieu of the great English country house. An idea for a novel had taken hold of him. When the time came to start the actual writing, he made an unusual decision. Lorna agreed to take over his share of the housework, while he would cancel all other commitments and do nothing but write, take his meals, and sleep, for a period of four weeks while he worked up a first draft of the book that became The Remains of the Day.

The story was told in the voice of Mr. Stevens, a retired butler who spent his adult life in the service of Lord Darlington. Stevens takes pride in his service; he admires his employer and has difficulty recognizing the implications of his master’s ill-judged political involvement. Out of a misguided sense of duty and a temperamental inability to express his emotions — including his love for a former colleague, the housekeeper Miss Kenton — Stevens has sacrificed his last chance for love, family, and independence.

Ishiguro’s crash program of writing accomplished its purpose. He had completed the essential elements of his book in four weeks and spent the next months revising and refining it. Shortly before publication, he made one last addition. He was so moved by an unexpected declaration of emotion in a song by Tom Waits that he decided Stevens too could be allowed one moment of self-awareness — a realization of all he has lost.

The book was published in 1989 to enthusiastic critical acclaim and enormous sales on both sides of the Atlantic. Any concern about supporting himself at a day job was now over, and he would be able to devote the rest of his working life to literature. The Remains of the Day received the English-speaking world’s highest literary honor, the Booker Prize (now known as the Man Booker Prize). A sensitive film adaptation of the novel was a commercial success and received eight Oscar nominations.

By age 35, Ishiguro had won Britain’s top literary honors. He was a bestselling author and entitled to enjoy the fruits of his success. Not only was he eager to keep writing, he now had the extra challenge of living up to an exalted reputation. Ishiguro startled critics and readers with his next novel, The Unconsoled (1995), a challenging work in stream-of-consciousness prose, describing the travels and travails of a concert pianist in an unnamed Central European country. Critics were sharply divided on the book’s merits — both admirers and detractors invoked the ghost of Franz Kafka — and sales were nowhere near those of The Remains of the Day, but its reputation has grown with the passing years.

Ishiguro knew popular success again, experimenting with elements of genre fiction in his next two novels. When We Were Orphans (2000) borrows the form of the detective story for other purposes, while Never Let Me Go (2005) adopts the method of dystopian science fiction. Set in an otherwise recognizable recent past, Never Let Me Go portrays a society where human clones are created and raised to young adulthood, only to be killed so that their organs can be harvested for transplant. The gruesome premise supports a haunting tale of doomed young love. A critical and popular success, it was also made into a compelling motion picture.

Over the years, Ishiguro continued to publish short stories in Granta and The New Yorker. In 2009, he published a collection of new tales: Nocturnes: Five Stories of Music and Nightfall. Ishiguro’s success also enabled him to resume his first creative love, songwriting. With composer and saxophonist Jim Tomlinson, he has written lyrics for a series of acclaimed albums by the jazz vocalist Stacey Kent. Ishiguro credits the discipline of lyric writing with teaching him a number of values he has carried over into his prose writing: a preference for the first-person narrator, compression, and the power of things left unsaid.

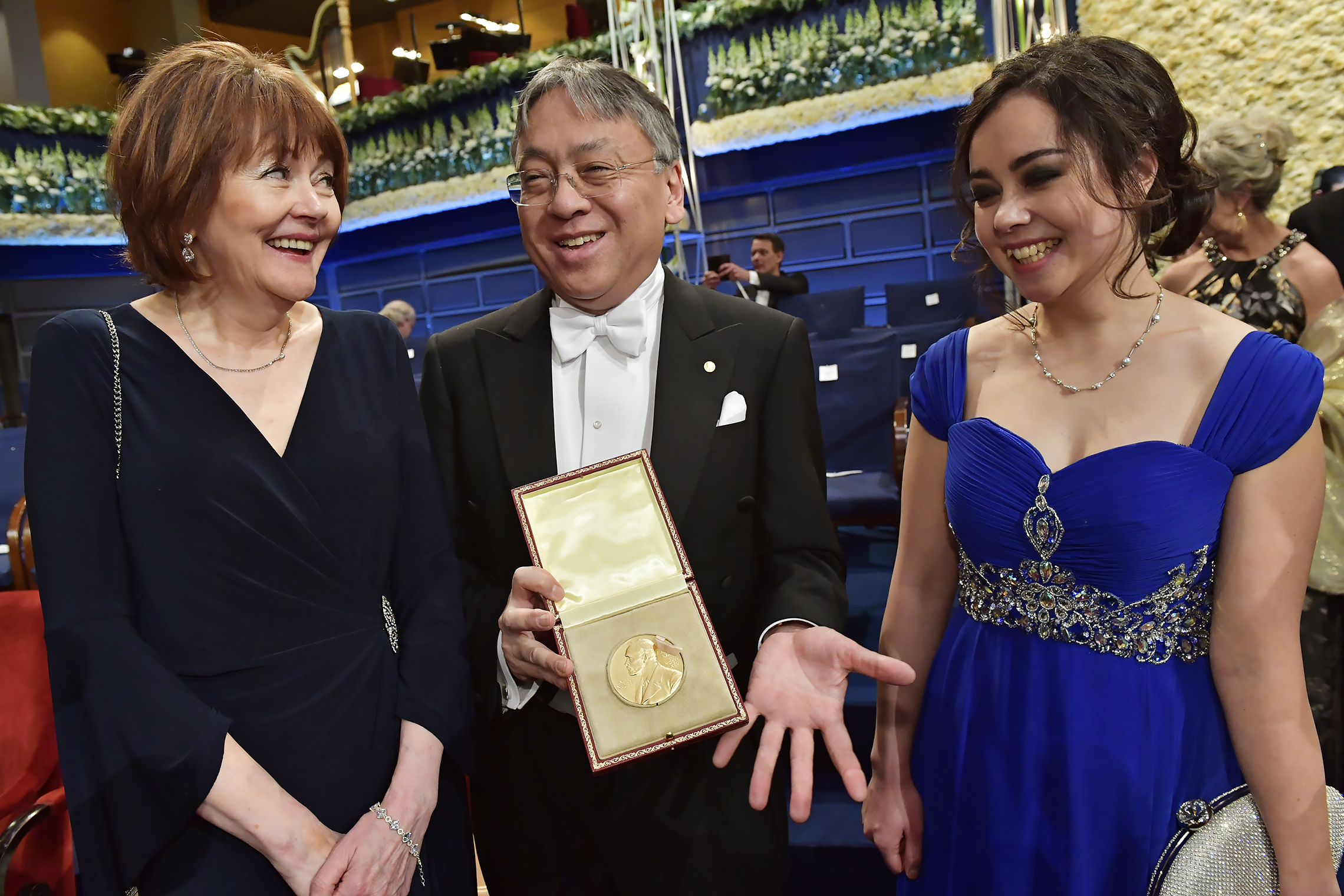

Kazuo Ishiguro created an original variation on another popular genre with The Buried Giant (2015), a magical fantasy of Britain in the Dark Ages, praised by The Guardian newspaper as “brave and bizarre.” With his works translated into nearly every language, Ishiguro’s popularity as a writer has grown while his critical reputation remains secure. In 2017, just weeks before attending the Academy of Achievement’s International Achievement Summit in London, Ishiguro learned that he had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. In making the award, the Swedish Nobel Committee noted that his “novels of great emotional force have uncovered the abyss beneath our illusory sense of connection with the world.”

In Klara and the Sun, his first novel since winning the Nobel Prize, we see the world of the near future through the eyes of an “Artificial Friend,” a synthetic human endowed with artificial intelligence who struggles to make sense of a human society very like our own. Back in the present, Kazuo Ishiguro lives in London with his wife, Lorna. They have one daughter, Naomi. He continues to write novels and songs, as the world awaits fresh surprises from this master storyteller.

Kazuo Ishiguro was born in Japan but moved to England with his parents when he was only five years old. His first two novels, both set in Japan, drew unanimous critical praise, but it was his third novel, set in England, that brought him international acclaim.

The Remains of the Day portrays the most English of settings and characters, the master and servants of a great country house in the years before World War II. The book’s evocation of a lost way of life, and its brilliantly expressed themes of memory, loss, and the power of heartfelt truths left unspoken, earned its author England’s highest literary honor, the Booker Prize. It sold over a million copies and was made into an acclaimed feature film.

Ishiguro’s subsequent works have ranged from the boldly experimental novel The Unconsoled to the dystopian fantasy Never Let Me Go — also made into a feature film. In his 2015 book, The Buried Giant, he explores the mythological Britain of the Dark Ages. With unerring skill and unbridled imagination, Ishiguro continues to surprise and delight his readers as the most daring and inventive novelist of his generation.

When did you first think of becoming a writer?

Kazuo Ishiguro: The first thing that really kindled my ambition to do anything like what I’m doing now is when I was 13 and I became fascinated by Bob Dylan. I had been listening to more kind of pop-type music, and then I came across Bob Dylan. And because of my age, I was relatively late coming to him. But then I went back over his catalog, and that’s when I became fascinated by words. And I discovered other great singer-songwriters of that era: Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell, some others. But these were very important people for me because of this fascinating relationship between what seemed to be a very literary language and the music form and the way they performed it. And so that’s what I wanted to be. It seemed to be the art form that I aspired to. And I did spend some time playing in folk clubs and to very small audiences. And I actually did a whole thing of carrying around demo tapes to recording companies and making appointments with A&R men. I did that whole thing, but quite rightly I got nowhere.

The lyrics of songs are so often in the first person, and that’s a point of view that you’ve adopted, too, as a novelist.

Kazuo Ishiguro: I think I learned an awful lot from writing songs. I wrote over a hundred songs. I still write song lyrics, actually, right now for Stacey Kent, a Grammy-nominated jazz singer. But back then, when I was a teenager, I wrote over a hundred songs. And I think that was part of my apprenticeship to be a writer of fiction. And many of the things I learned writing songs — being this bad singer-songwriter — I think became fundamental to my style as a fiction writer. And one of the things you point out — there is something about that kind of singer-songwriter tradition that is very first-person. More than that, I would say there is something of the atmosphere of just one singer communicating with just a handful of people in a room with an acoustic guitar. That kind of atmosphere, that intimacy, is something I still go for when I’m writing a novel. Also, I think there are many other things I learned at that point. I think the fact that, when you’re writing a song, you don’t have many words to use. I mean you’re very restricted in terms of the amount of words you can use. And because there is performance in music, along with the words, you have to leave a lot of things out in the words. If the words are complete unto themselves, as poetry on the page would be, the thing will not work. So this idea that a lot of the emotion, a lot of the meaning of what you’re doing, is hidden, is between the lines, necessarily had to be between the lines. You have to avoid making things too explicit in the words to leave space for the performance, for the music and the performance — the singing, if you like, and the music — so that they had something important to do. I think these are all things that I took into my writing style, and I think that remains core to my style today.

You went to the graduate creative writing program at the University of East Anglia. Those programs weren’t as common in Britain then as they were in America.

Kazuo Ishiguro: At the time when I was accepted in the creative writing course at the University of East Anglia, it was the only one in Britain that was an accredited master’s degree. And even at that university, it was not respected. The traditional English dons thought it was a ridiculous thing. It’s only because it was run by this very powerful and esteemed novelist and academic, Malcolm Bradbury, that it was allowed to run. And even then people didn’t apply for it. The year before I went, it didn’t run because nobody had applied, and the same the year after. So there’ll usually be — in my year, there were six, and I think it was the largest ever. And Ian McEwan was famous for having done that course ten years earlier. But beyond that, it wasn’t seen as a respectable way for serious literary British novelists to start a career. It was seen as a very strange idea.

I wasn’t even trying to be a writer at that point, but I’d been working with homeless people in London for a year after I’d left the university from studying my first course. And I thought, “Well, it’d be very nice to do a postgraduate degree.” And I applied to a number of things. That just happened to be the creative writing one. I just came across it almost by chance, and it said that instead of a scholarly thesis, I had to just submit a work of fiction of only 30 pages. So I thought, “Well, this sounds like a much easier task.” But of course, when I got accepted, I started to panic. I thought everybody was, you know — I was going to meet a lot of brilliant, genius, budding writers, and I didn’t have a clue how to do this. And I had been accepted on the strength of a radio drama I had written. So I did actually rather panic. And the summer before I went to the University of East Anglia, I locked myself up in a cottage in the middle of nowhere in the west of England, in Cornwall, in a very remote part of Cornwall. And for four weeks, I just wrote and wrote and wrote. I hardly saw anybody else. And I kind of learned to write.

There weren’t texts. It’s hard to believe that there really wasn’t a creative writing industry, if you like. It wasn’t a discipline. I have mixed views about the growth of creative writing as a kind of formal, taught discipline. But anyway, for me that kind of worked. But a lot of things happened to me before I got to that course.

And I discovered that I didn’t think it was that big a leap from what I’d been doing already, writing songs and then writing short stories. Some writers talk about their early works, the juvenilia. They often talk about secret novels that are hidden somewhere in their house. That’s rather embarrassing. My equivalent is those songs. I went through my adolescent autobiographical phase in those songs. So when I started to write fiction quite seriously, I came in at a later point. I’d already gone through a lot of the typical phases.

So my first novel is told from the point of view of someone very different from me, living in a different era. A Japanese woman in her 60s recording the war years in Japan. Very different to who I was then, a young man living in England in the 1970s. But I think I was able to do that because I had worked through a lot of the typical stages that people go through.

You had unusually early success as a writer of fiction, having your first novel published, and then the second novel won major awards. And then The Remains of the Day won the Booker Prize. That great good fortune near the beginning of your career, what effect might that have had on you as a writer?

Kazuo Ishiguro: I felt it was almost entirely positive for me. I felt it took pressure off me. You know, I didn’t have to worry about winning prizes. There was something about the climate in those days. I know that literary prizes have always been around in Britain, as well as in the United States and everywhere else. But somehow they came into the public eye in a big way around the time when I started to write.

The idea that novelists could almost be showbiz was introduced into the air and people were being signed up for big advances and so on. The book prizes became quite glamorous things in that era. So if you were seen to be a rising young novelist, there was enormous pressure in terms of prizes. I think there’s a parallel here with rising classical musicians. They have to win music competitions. Something almost like that was going around, I would say, in Britain in the 1980s.

I felt that winning all the major prizes by the time I was in my mid-30s just took away that pressure because I always feared that it would distort my artistic direction. It would make me cowardly; it would make me play safe. My novels could become a series of applications for prizes, trying to second-guess what juries would like and what they wouldn’t like. So looking back now, I feel it was a real blessing that I got the prizes out of the way. Of course, I never expected to win the Nobel, so I thought — by the time I won the Booker at the age of 34, I thought, “Well, I’ve done the prizes; now I can just forget about prizes.” And I think that’s quite important because I think there’s something about writing. One of the great joys and powerful things about writing is it’s a solo activity. I love cinema. I admire theater. These are collaborative art forms, and they produce great work. But there’s something special for me about the fact that when someone writes a novel, it’s just one person. When I’m reading a novel, I’m communicating with just a single consciousness. I think that’s very special. And I think, for that reason, it’s kind of important that a person is not exactly left alone, but we shouldn’t think too much about the worldly aspect of a writing career when we’re trying to create. And it’s very difficult not to. You’re human. And to be liberated from worrying about prizes — where you are in the pecking order — I think that, for me, was a tremendous freedom.

In The Remains of the Day, it’s in the first person, in the voice of this very correct English butler, far removed from your own life, but there’s a way you pull the reader in as well. He says, “I’m sure you know some of the great butlers of our day,” and the reader is in on it. “I’m sure you realize how important it is to have a staff plan.”

Kazuo Ishiguro: Yeah, it is very conscious. It’s a technique thing. The “you” that the narrator in The Remains of the Day, for instance, addresses, that “you” isn’t the reader. In all these books, I like the idea of the narrator addressing a “you” because their perspective is so small that they can’t imagine that they’re addressing anybody outside of their very small world. Stevens is a butler. The “you” he addresses is another butler, or at least another house servant of some sort, who lives in this world of serving in country houses. The reader is kind of eavesdropping on a conversation between this butler and another butler. That’s the effect I want to give.

What’s important to me is these books are to a large extent about what happens when your perspective is very narrow. Books like The Remains of the Day and the one before that, they’re about people who desperately want to contribute something to the good of the world. They want to be proud of how their work contributed to something good. And in many ways, they’re very decent people, but because they’re not remarkable in their perceptive powers, because their perspective is so parochial and small, they cannot see where they fit in in the larger historical context. And they find that their lives are compromised. They have contributed unwittingly to bad, or into evil things, and it’s just they’re unlucky. Stevens is unlucky because he happened to live through those fascist years.

It’s not his fault in a way. But his career — his best efforts — are entwined with those of the man he served as a butler, who in this case turned out to be a Nazi sympathizer. So in all of these books it’s very important to me to suggest the narrow perspective, the small world that he cannot see beyond. This is one of the things that I’m trying to portray. I’m trying to say that all of us struggle to see beyond our small world. It’s very difficult for any of us to have a special perspective. We all do jobs just like this butler. Many of us do our best. We work very hard and we create something and we offer up our services or whatever we do to somebody upstairs. And it’s often an act of faith. It will be used well. It will be used for something good, as a company or a boss or a nation, somebody that’s going to use it. You just hope your contribution is going to be used for something good. But we often don’t have the perspective to see what’s really going to happen with our little contribution. That’s the fate of Stevens the butler. I’m trying to suggest that many of us, perhaps most of us are in this situation where morally and politically we’re butlers. So it’s very important for me to create that sense that he can’t imagine addressing somebody other than another house servant.

He’s so obsessive about being a fine butler that he forgets to have a life of his own. He comes very close to love and it doesn’t quite happen. It’s a sense of giving up your life for your work and your self-delusion.

Kazuo Ishiguro: Many of us do that. That’s part of what the modern world is, it seems to me. It’s not because he’s a wage slave. It’s not because he needs to make the money. It’s because it really matters to him that he does his work well. His sense of dignity, his sense of self-respect, come from that. But being the perfect butler, as he defines it, seems to preclude human love. It precludes a lot of things. But it seems to me a lot of us, a lot of people I meet, we live that kind of life now. I think there are many pressures in the modern world, perhaps even more so than when I wrote that novel, that push people to have those kinds of priorities.

You must have done a lot of research for that book before you started writing.

Kazuo Ishiguro: Yes. Yes, yes. This is a big question. I’ve never quite figured this out. When is the best time to actually start doing the actual writing? The writing of the words that go into the book? Never mind how many drafts you’re going to do. When do you actually start the proper writing? If you start too early, you can’t write certain kinds of books. You can’t write that kind of very carefully structured novel where something that happens on page 28 is picked up again on page 94 and there’s a tremendous reverberation. You can’t set things up in that way. You’re kind of improvising. But you can get some kind of strange force out of that kind of serendipity and improvisation, and you can bypass your own senses in a way and surprise yourself, even shock yourself with what comes out. However, as I say, you don’t have the same kind of control.

So that question of how much should you know about your story, how much research should you have done — I don’t just mean into the historical background, I mean research into the characters, the relationship your fictional world would have to everyday reality — all these things. How much of that should you already know before you actually start the book? I’ve never been able to settle on a consistent rule about this. I think this is one of the most important decisions for any novelist, putting yourself somewhere on that spectrum. Are you one of the writers, at least for this book, that starts with almost no idea and then you end up with something beautifully messy that you can then shape and reshape if you want? Or do you do quite a lot of planning? Do you know quite a lot of things and then you proceed quite carefully? There are pros and cons to both approaches.

So The Remains of the Day, I had to do a lot of just straightforward, kind of historical research, as a scholar would do. I was in the library a lot. I was reading, actually, things written at the time — in the 1920s, 1930s — political pamphlets, biographies of nonentities who thought they were terribly important, and they’d write their autobiography. There were a lot of aristocrats in Britain who felt the world should know all about them. But actually, they were very revealing. I read fascinating things like Sir Oswald Mosley’s autobiography. Mosley was the British fascist, leader of the British Union of Fascists. His justifications for what he had done, later in life — these things were all fascinating. So I did an enormous amount of historical research. Some of it was just for my interest. But then, at some point, I had to start writing my novel. And I did this crash.

We’ve read that you wrote much of that book in about four weeks in what you called a “crash program.” Could you tell us about that?

Kazuo Ishiguro: I kind of experimented with this idea — my wife colluded in this — that I should actually cut myself off from the outside world for four weeks, as much as was possible. So I didn’t answer the phone. I didn’t go outside. I had an hour off for lunch, two hours for dinner. Then I would go back to work again. I think I used to just get Sundays off. But the idea was, “What would happen if I absolutely incarcerated myself into a tiny room? Would the fictional world become more real than the world outside?” I don’t know why the word “crash” was used, but several other writers picked up on this, and they started to say, “I might try a ‘crash’ now.” There’s no logic to it. But the first time I tried it was for The Remains of the Day, and I think it worked very well, in that, in those four weeks, I think I had all the foundation for the book. Then I had to kind of go back and figure things out, make it more stylish, get that voice right. But all the important things, all the important central artistic decisions, were made in those four weeks.

You’ve mentioned the impact of listening to a song by Tom Waits when you were writing the last draft of The Remains of the Day. Is that right?

Kazuo Ishiguro: Actually, I had done what I thought was more or less a finished version of The Remains of the Day, but the very buttoned-up narrator, the butler — in that earlier version, he doesn’t quite come through confessing his true emotions. He maintains his front a little bit more effectively than he does in the final version. What made me change my mind was that, between that penultimate version and the final version I handed in, I listened to a song by Tom Waits — another great singer-songwriter, remarkable artist. And this is the power of that art form: it’s performance as well as the actual writing.

I was listening to a song called “Ruby’s Arms,” but it could have been any number of Tom Waits songs. And in the middle of that — it’s a song about a soldier just leaving, or somebody, just leaving his girlfriend, sneaking out in the morning to get on a train. But there’s a moment in that when Waits sings the words “although my heart was breaking.” And it’s not so much the words themselves; it’s the way he sings them because Waits sings — his voice sounds like kind of a really rough, tough, hobo-type character, not accustomed to revealing his emotions at all. And it’s the way that this emotion seems to break through all his customary defenses. This is all in that voice. You know that that is not the voice of a man who normally talks about his own heartbreak. But he just cannot hold it back anymore. And this is the power of song when it’s sung by a great singer and he writes great songs. You can do this.

And I thought, “Oh, I’d love to — can I do something equivalent in my novel?” So in a novel, there is no singer, but I’ve maintained this very buttoned-up — repressed, you might say — controlled voice of a narrator all the way through. Shouldn’t I let him just break? Shouldn’t I let the big, big emotion break through just once? Would it have an equivalent effect? So I changed things a little bit. I allowed that armor to be pierced. I learn an awful lot from listening to music and songs. I learn a lot from other writers, but I learn a huge amount from watching films and listening to people like Tom Waits and Dylan and Leonard Cohen.