Great achievers are driven, not so much by the pursuit of success, but by the fear of failure.

Lawrence J. Ellison was born in the Bronx, New York. At nine months, he contracted pneumonia, and his unmarried 19-year-old mother gave him to her aunt and uncle in Chicago to raise. Lawrence was raised in a two-bedroom apartment on the city’s South Side. Until he was twelve years old he did not know that he was adopted. His adoptive father had lost his real estate business in the Great Depression and made a modest living as an auditor for the public housing authority. As a boy, Larry Ellison showed an independent, rebellious streak and often clashed with his adoptive father. From an early age, he showed a strong aptitude for math and science, and was named science student of the year at the University of Illinois.

During the final exams in his second year, Larry Ellison’s adoptive mother died, and he dropped out of school. He enrolled at the University of Chicago the following fall, but dropped out again after the first semester. His adoptive father was now convinced that Larry would never make anything of himself, but the seemingly aimless young man had already learned the rudiments of computer programming in Chicago. He took this skill with him to Berkeley, California, arriving with just enough money for fast food and a few tanks of gas. For the next eight years, Ellison bounced from job to job, working as a technician for Fireman’s Fund and Wells Fargo Bank. As a programmer at Amdahl Corporation, he participated in building the first IBM-compatible mainframe system.

In 1977, Ellison and two of his Amdahl colleagues, Robert Miner and Ed Oates, founded their own company, Software Development Labs. From the beginning, Ellison served as chief executive officer. Ellison had come across a paper called “A Relational Model of Data for Large Shared Data Banks” by Edgar F. (“Ted”) Codd, describing a concept Codd had developed at IBM. Codd’s employers saw no commercial potential in the concept of a Structured Query Language (SQL), but Larry Ellison did.

Larry Ellison and his partners won a two-year contract to build a relational database management system (RDBMS) for the CIA. The project’s code name: Oracle. They finished the project a year ahead of schedule and used the extra time to develop their system for commercial applications. They named their commercial RDBMS Oracle as well. In 1980, Ellison’s company had only eight employees, and revenues were less than $1 million, but the following year, IBM itself adopted Oracle for its mainframe systems, and Oracle’s sales doubled every year for the next seven years. The million-dollar company was becoming a billion-dollar company. Ellison renamed the company Oracle Corporation, for its bestselling product.

Oracle went public in 1986, raising $31.5 million with its initial public offering, but the firm’s zealous young staff habitually overstated revenues, and in 1990 the company posted its first losses. Oracle’s market capitalization fell by 80 percent, and the company appeared to be on the verge of bankruptcy. Accepting the need for drastic change, he replaced much of the original senior staff with more experienced managers. For the first time, he delegated the management side of the business to professionals, and channeled his own energies into product development. A new version of the database program Oracle 7, released in 1992, swept the field and made Oracle the industry leader in database management software. In only two years the company’s stock had regained much of its previous value. Even as Oracle’s fortunes rose again, Ellison suffered a series of personal mishaps. Long an enthusiast of strenuous outdoor activities, Ellison suffered serious injuries while body surfing and mountain biking. He recovered from major surgery, and continued to race his 78-foot yacht, Sayonara, and to practice aerobatics in a succession of private jets, including decommissioned fighter planes. In 1998, Ellison and Sayonara won the Sydney-to-Hobart race, overcoming near-hurricane winds that sank five other boats, drowning six participants. Ellison is a principal supporter of the BMW Oracle Racing team, which has been a significant force in America’s Cup competition. His yacht Rising Sun, over 450 feet long, is one of the largest privately owned vessels in the world.

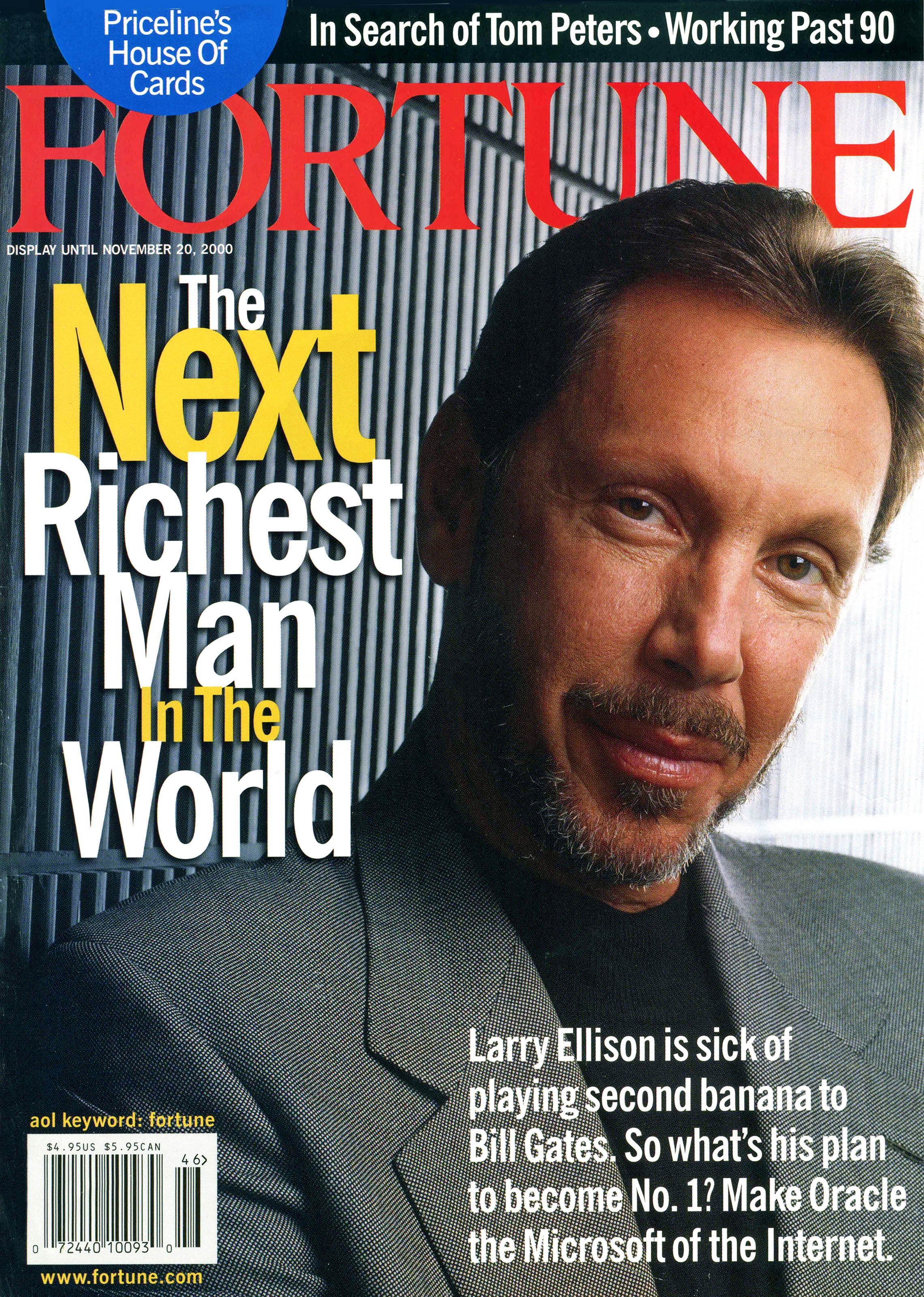

Oracle’s fortunes continued to rise throughout the 1990s. America’s banks, airlines, automobile companies and retail giants all came to depend on Oracle’s database programs. Under Ellison’s leadership, Oracle became a pioneer in providing business applications over the Internet. Oracle benefited hugely from the growth of electronic commerce; its net profits increased by 76 percent in a single quarter of the year 2000. As the stocks of other high-tech companies fluctuated wildly, Oracle held its value, and its largest shareholder, founder and CEO Larry Ellison, came close to a long-cherished goal, surpassing Microsoft founder Bill Gates to become the richest man in the world. Beginning in 2004, Ellison set out to increase Oracle’s market share through a series of strategic acquisitions. Oracle spent more than $25 billion in only three years to buy a flock of companies and large and small makers of software for managing data, identity, retail inventory and logistics. The first major acquisition was PeopleSoft, purchased at the end of 2004 for $10.3 billion. No sooner was the ink dry on the PeopleSoft deal than Ellison trumped rival SAP to acquire retail software developer Retek. Within the following year, Oracle also acquired competitor Siebel Systems. Ellison capped this buying spree with the acquisition of business intelligence software provider Hyperion Solutions in 2007. Two years later, in the depths of a global recession, Ellison once again acted boldly, acquiring computer hardware and software manufacturer Sun Microsystems for $7.4 billion. Oracle became the world’s largest business software company, supplying all 100 of the Fortune Global 100.

After many years of pursuing a victory in the America’s Cup yacht race, Ellison triumphed at last in 2010. Ellison joined the crew of the BMW Oracle for the second leg of the two-day competition, when the giant trimaran, with its revolutionary 223-foot wing sail, ended the race five minutes and 25 seconds ahead of the second-place finisher. Ellison’s victory brought the 159-year-old America’s Cup, the oldest trophy in international sports, back to the United States for the first time in 15 years.

The America’s Cup race is scheduled by agreement between the defending champion and the challenger who has qualified through a preceding series of races. In recent decades, the contest has been held roughly once every three years. The United States, represented by the Golden Gate Yacht Club and Ellison’s Team Oracle had their first opportunity to defend their hard-won title in September 2013. At Ellison’s insistence, the 2013 contest was held in San Francisco Bay, where it could easily be witnessed by spectators on shore. The contest consisted of a series of races, with the cup going to the first team to win nine races. Both teams now raced wing-sail catamarans. The competing craft would be the most technically sophisticated — and most expensive — racing yachts ever built. The opening rounds went badly for Team Oracle, with challenger New Zealand Emirates taking the lead. New Zealand won the first eight races, apparently dooming the Oracle team to defeat. In a stunning turnaround, Oracle took the next race, and the next, and the next, winning the contest nine races to eight. Just as Ellison revolutionized the world of business software, so has he transformed the sport of yacht racing.

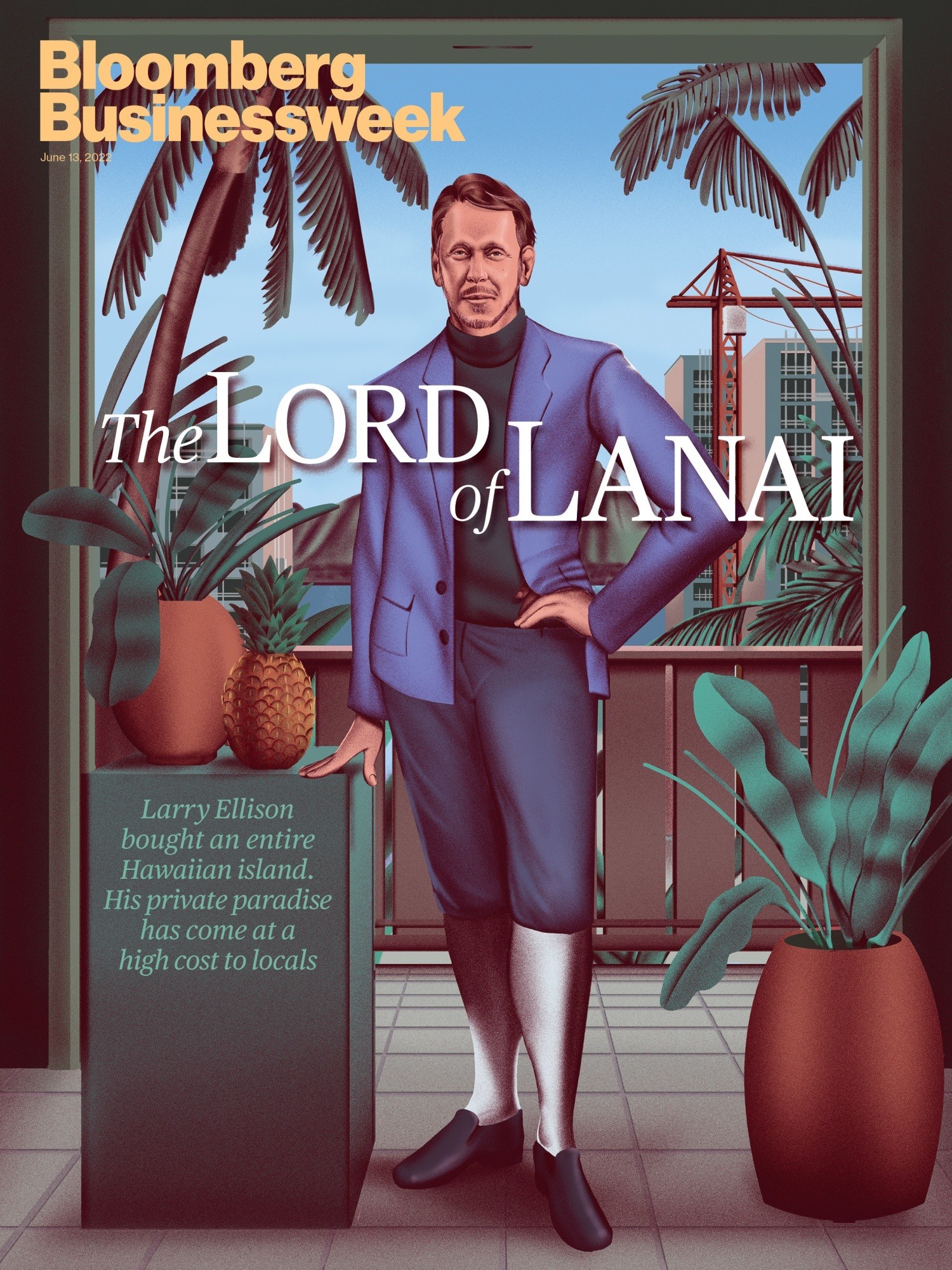

Larry Ellison maintains principal residences at Carbon Beach in Malibu, California and in Woodside, California. In 2012, Ellison purchased 98 percent of the Hawaiian island of Lana’i; the remainder is owned by the State of Hawaii. The price was not made public but was reported to be as high as $500 million. Ellison announced plans to make the island into “the first economically viable, 100 percent green community.”

Larry Ellison served as President of Oracle from 1978 to 1996, and undertook two stints as Chairman of the Board, from 1990 to 1992 and again from 1995 to 2004. For the company’s first 37 years, he was Oracle’s only chief executive officer. In 2014, he relinquished the role of CEO, entrusting the post to two longtime associates. He now holds the role of Executive Chairman and continues to serve as Chief Technology Officer. He remains the company’s most visible spokesperson.

In 2016, Ellison’s personal fortune was estimated at $50 billion, second only to that of Microsoft’s Bill Gates. In May of that year, Ellison donated $200 million to the University of Southern California to create a new cancer research center in West Los Angeles. The gift matched the largest single donation ever received by the university. The Lawrence J. Ellison Institute for Transformative Medicine will deploy experts in physics, biology, math, and engineering in a coordinated effort to prevent, detect, and treat cancer.

Larry Ellison’s sporting interests extend to sponsorship of professional teams. From 2006 to 2019, the basketball venue in Oakland, where the Golden State Warriors played, was known as Oracle Arena. In 2019, Oracle purchased 20-year naming rights for the baseball stadium of the San Francisco Giants, now known as Oracle Park. In October of that year, Forbes magazine estimated Ellison’s personal fortune at $69.1 billion.

Already dominant in business systems, from payroll services to hotel and airline booking and medical record keeping, Oracle has continued to expand in new areas of the tech economy. In 2017, Ellison led Oracle through its largest acquisition to date, paying an estimated $9 billion for the cloud-software provider NetSuite Inc. In the following years, Ellison moved aggressively to position Oracle at the forefront of the cloud computing sector, luring high-priced talent from industry leader Amazon Web Services.

At the same time, Ellison made one of the most fateful strategic investing choices of his career. In 2018, he spent approximately $1 billion to buy 15 million shares of Tesla, Inc., the clean energy company best known for its innovative electric automobiles. This investment made Ellison one of the company’s biggest individual shareholders, second only to the company’s founder, Ellison’s friend Elon Musk. At the end of the year, Ellison joined Tesla’s board of directors.

In 2020, an unexpected convergence of events provided Oracle with greater opportunities. When the Covid-19 pandemic drove business to the virtual meeting space Zoom, Oracle provided Zoom with the extra capacity the video conferencing app needed to meet the demand.

In autumn 2020, Oracle sought to become the American partner of the popular Chinese video-sharing app TikTok. Under the terms of a provisional agreement, Oracle would pay $7 billion or more to acquire a 12.5 percent stake in the new U.S.-based TikTok and guarantee the security of users’ information. A final agreement depends on approval from both the U.S. and Chinese governments, a matter that remains in doubt. Less doubtful is the outcome of Ellison’s investment in Tesla. In a little more than two years, Ellison’s stake in the company had increased in value from $1 billion to $13 billion. In June 2023, the optimism around artificial intelligence drove Oracle Corp.’s stock and founder Larry Ellison’s net worth to record highs. In May 2024, Larry Ellison had a net worth of $141 billion, primarily from his shares in Oracle. A decade after stepping down as Oracle’s CEO, Ellison was still chairman, CTO, and its largest shareholder, owning 40% of the company. Oracle stock had increased by 34%, providing over $1 billion (pretax) in dividends to Ellison over the previous 12 months, making him $34 billion wealthier.

In 2023, Ellison led Oracle’s resurgence by capitalizing on the surge in demand for AI computing power, positioning the company as a key player in cloud infrastructure. As Oracle’s stock climbed 90%, Ellison’s wealth grew to $196 billion, putting him on the verge of surpassing Jeff Bezos as the world’s second-richest person. In 2024, Ellison predicted that training future AI models could cost $100 billion each, leading to a huge market that would be dominated by a handful of companies for the next decade, highlighting Oracle’s critical role in this evolving market.

News emerged in November 2024 that Ellison played a pivotal role in the University of Michigan football program by helping secure Bryce Underwood, the nation’s top high school quarterback. This revealed Ellison’s personal connection to Michigan through his new wife, Jolin Zhu, a Michigan alumna with a degree in International Studies. Quietly supporting Michigan’s Champions Circle booster group, the couple’s contributions and personal engagement were key factors in one of college football’s most unexpected recruiting victories. In July 2025, Ellison’s net worth is estimated to have soared to $275.9 billion, making him the second richest person in the world, behind Elon Musk, thanks to a surge in Oracle’s stock driven by its booming cloud computing business.

On July 24, 2025, under Larry Ellison’s leadership and influence, Paramount Global completed an $8.4 billion merger with Skydance Media. The Federal Communications Commission approved the transaction after an extensive review, citing assurances from Skydance that the new company would focus on unbiased journalism at CBS News and would not implement diversity, equity, and inclusion programs. As a condition of approval, Skydance also committed to appointing an official to oversee fairness in its news division. David Ellison, Larry Ellison’s son, is set to lead Paramount following the merger, marking a new chapter for the company’s leadership. The deal was the culmination of a protracted process that drew widespread public attention and debate about the role of business and government in shaping media organizations.

Beyond media and technology, Ellison also set his sights on reshaping the world of higher education. In 2023, he purchased Oxford’s historic Eagle and Child pub, once frequented by literary greats J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis, and began funding the creation of the $1.3 billion Ellison Institute of Technology, a private research campus developed in partnership with the University of Oxford. Scheduled to open in 2027, the institute will focus on artificial intelligence, robotics, healthcare, and food security, offering scholarships, joint research opportunities, and significant financial support to Oxford.

In September 2025, Ellison surpassed Elon Musk to become the world’s richest person after Oracle’s market value rose by more than $200 billion, propelled by the surging demand for artificial intelligence. That same month, OpenAI signed a $300 billion deal with Oracle to purchase computing power over five years, one of the largest cloud contracts in history. The announcement added $317 billion in future revenue to Oracle’s books, sending its stock price up more than 40% and boosting Ellison’s net worth by over $100 billion in a single day.

“It’s my job for Oracle — the number two software company in the world — to become the number one software company in the world. My job is to build better than the competition, sell those products in the marketplace, and eventually supplant Microsoft and move from being number two to number one.”

When Larry Ellison first expressed these goals for his company, more than a few people thought his ambition laughable. Oracle led the software pack in relational database technology, but many observers saw this as a mere niche market in the industry, while mighty Microsoft provided the operating systems and office software in the coveted personal computer sector.

By the year 2000, Larry Ellison had drawn within reach of his goal. In a single quarter, the company’s net profits increased by an astounding 76 percent. As the value of Microsoft and other high tech stocks fluctuated wildly, Oracle not only maintained its value, but gained. His strategic acquisitions of PeopleSoft, Siebel Systems and Sun Microsystems made Oracle the world’s leader in business software. Payroll systems, hospital records, hotel and airline reservation booking around the world are all managed by Oracle software. Oracle continues its expansion in the ever-growing cloud computing sector and Larry Ellison routinely ranks as one of the world’s wealthiest individuals.

How did you become involved with relational database programming?

Larry Ellison: Relational database technology was invented by a guy by the name of Ted Codd at IBM. It’s based on relational algebra and relational calculus. It is a very mathematically rigorous form of data management that we can prove mathematically to be functionally complete. This work was done in the early seventies by an IBM fellow by the name of Ted Codd. He published his papers, and really, based on those publications, Oracle decided to see if we (we were four guys) couldn’t beat IBM to market with this technology, based on the published IBM research papers. And in fact we did.

What is the biggest obstacle you’ve ever had to face in your professional life? Was there a time that you thought you actually might fail?

Larry Ellison: There were lots of times, especially in the early days, that were very, very difficult. I think the most difficult experience I had was in 1990 when Oracle had its only loss quarter in history. We’d been in business for 20 years, and after 20 years we lost money one quarter. We had a very difficult time. We had virtually doubled our sales every year for ten years. Nine out of ten years, ten out of eleven years. It was really quite an amazing run. We were the fastest growing company in history, and still are the fasting growing company in history over a long period of time.

Suddenly we hit a wall. We reached a billion dollars in revenue, and we were having serious management problems all over the place. The people who were running the company, the billion-dollar company, were the same people that had run the company when we were a 15 million-dollar company, one twentieth the size. I had an incredible sense of loyalty to those people who had worked with me to build Oracle. It was a very painful realization in 1990 that I was going to have to change the management team. The company had outgrown the management. People who are good at running a 15 million-dollar company don’t use the same skills. They’re just different, not one is better or worse, just an entirely different skill set in running a 15 million-dollar company than a billion-dollar company. Both skill sets are rare and precious. But we needed a different group of managers, and virtually the entire management team had to be replaced. That means I had to ask people who I had worked with for a decade to leave. I had to fire people. That was the most difficult thing I had to do in business, asking a bunch of people to leave Oracle.

What kept you going through that time?

Larry Ellison: That I had no choice. I had to ask them to leave Oracle, or everyone had to leave Oracle, because there wouldn’t be any Oracle left. In that sense, it was a simple choice. Thousands of people worked for Oracle. They deserved the best leadership you could find. My primary responsibility was to the company and to all of the staff, all of our shareholders, and all of our customers. Therefore, I had to choose. And if I couldn’t make that decision, then I had to go.

People have accused you of launching some brutal attacks on your competition. Is that an okay thing to do?

Larry Ellison: Were you shocked by the way we treated Iraq? We were incredibly aggressive against them. Was that really right? Of course we were aggressive against the Iraqis. They invaded Kuwait, they were threatening our oil supplies, they were threatening the world order. It was the job of our armed forces to defeat the enemy.

It is my job to go out into the marketplace and win. We run ads that compare our products to the competitors’ products. We don’t lie about this, we just say, “We can do this; they can’t.” We name the competition, it’s fact-based advertising. We say very clearly that we’re faster, and these tests prove it. We’re more reliable, and these tests prove it. We’re more economical, and so we’ll name a competitor. Even if the facts are true, it’s considered a little bit rude by some people. I don’t think it’s immoral. I think that we’re giving true facts to customers, giving valuable information to customers so they can make better decisions. It is Bill Gates’s job to make Microsoft the biggest company on earth, that’s what he’s paid for. It’s my job for Oracle — to move from the number two software company in the world to become the number one software company in the world. That’s my job, that’s what I’m paid for. If I’m not aggressive enough in the pursuit of that, if I’m not successful in the pursuit of that, I should be gotten rid of. If the general running Desert Storm is not aggressive enough and successful enough in the pursuit of that goal, he should be fired.

I don’t think it’s immoral. I think that we’re giving true facts to customers, giving valuable information to customers so they can make better decisions.

Larry Ellison: The corporation’s primary goal is to defeat the competition in the marketplace. My primary function is to make Oracle successful, to make it a good and interesting place to work, because we don’t want people to leave. This is America, people can change jobs, and people like to work with other intelligent and interesting people. They like to do interesting things. We have fantastic salary scales; I think we’re the highest paying company in Silicon Valley. We have wonderful benefits, all of these things, but again, don’t mistake any of that for altruism. That is in our interest, to retain our employees. Their job, my job, is to build better products than the competition, sell those products in the marketplace, and eventually supplant Microsoft and move from being number two to number one. That is our reason for being.

What are you like as an employer?

Larry Ellison: The corporation’s primary goal is to defeat the competition in the marketplace. My primary function is to make Oracle successful, to make it a good and interesting place to work, because we don’t want people to leave.

There are networks everywhere: around the world, in offices, in schools, in major government institutions. So why not have computer networks that are similar to television networks or telephone networks? A television network is enormously complicated. It has got satellites and relay stations and cable head-ins and recording studios. You have this huge, professionally managed network, accessed by a very low-cost and simple appliance, the television. Anyone can learn how to use a television. Ninety-seven percent of American households have televisions. Ninety-four percent of American households have telephones. The telephone: again, a very simple appliance attached to an enormously complex, professionally managed network. Why shouldn’t the computer network be just the same?

Oracle is the number one software company in the world for providing technology to manage information. But we’re only the number two software company overall. Microsoft is the number one software company. But right now we’re living at the dawn of the information age, not the dawn of the PC age. So we’re wonderfully positioned to pass Microsoft and become number one. That’s my job. The personal computer was designed as a stand-alone device. There was no Internet around in 1981 when the PC was invented. There weren’t a lot of local area networks in schools and government agencies back in 1981, but the world has changed.

Larry Ellison: I decided to go into the computer business in college. I started working part-time programming. I found that in a very short period of time, I could make more money writing programs than a tenured professor at the University of Chicago was making, and I was a teenager. I said, “Well, this is kind of cool.” It was also fun, it was like a big game, it was like working on puzzles. So I enjoyed it. It paid extremely well, I could work at home, I could work my own hours. I closely associated with computers, because they were absolutely a slave to reason, they knew nothing about fashion. They were completely logical. I enjoyed spending time with them. I liked what I was doing, it was very profitable, and it was very creative. It was also giving me immediate feedback. I could start writing a program, and within several hours, I could have a result. Freud defines maturity as the ability to defer gratification. The great thing about programming is you don’t have to be mature at all. You don’t have to defer gratification for more than a few hours. You get wonderful, tight feedback. It’s a lot of fun. That’s characteristic of games and sports. The reason why games and sports are so popular is because you win or lose very quickly. You get immediate feedback. It’s a very tight loop, you don’t wait hours or days or years before you find out if you’re winning or losing. You find out a second-and-a-half after you release that basketball. You know whether it’s going in or not.

How did you land that first job?

Larry Ellison: It was in school, and they noticed when I was writing programs for school, I was getting done faster than everybody else. They offered me a job. I figured out very, very quickly that rather than being paid by the hour, I was much better off being paid by the program. I was working at the university, and then I started doing consulting for local businesses. That worked very well.