That's how our democracy functions. That's how we are able to govern and deal with the challenges we face, is when people are willing to come together — regardless of party, regardless of ideology — and work together, find compromise and get things done. That's the heart and soul of our democracy.

Leon Panetta was born in the seaside city of Monterey, California, the second son of Carmelo and Carmelita Panetta, immigrants from Calabria in Southern Italy. When Leon Panetta was a small boy, his parents operated a restaurant in downtown Monterey, while his maternal grandfather, a retired merchant seaman, looked after Leon.

The advent of World War II brought an influx of military personnel to nearby Fort Ord, a boon to the Panetta family restaurant business, but when the United States officially entered the war, Leon’s life changed abruptly. Fearing espionage and sabotage, the government imposed restrictions on citizens of the enemy nations: Germany, Italy, Japan, and their allies. Although Leon Panetta’s parents were naturalized citizens of the United States, Leon’s grandfather was still an Italian citizen and was ordered to relocate farther from the coast. Young Leon rode with his parents and grandfather to San José, where they left the grandfather in a boarding house with other relocated Italians. Although the impositions on German and Italian nationals were far less severe than those visited on Japanese — or even on American citizens of Japanese ancestry — the loss of his grandfather’s presence in his daily life was a blow for young Leon, his first experience of the injustice that can occur when fear overcomes reason.

The Panettas’ family business prospered, and after the war, Leon’s parents sold their restaurants and bought a farm in the nearby Carmel Valley, where they raised fruit, walnuts, and almonds. Despite their unhappy experience during the war, the elder Panettas taught Leon to be grateful to the United States for all it had given them and to seek ways to serve his country. Leon did well in Catholic grammar schools in Monterey and Carmel, and at Monterey High School, where he became active in student politics. He graduated magna cum laude from Santa Clara University, a Jesuit institution, with a degree in political science. He remained at Santa Clara to study law and, in 1962, married Sylvia Varni, a nursing graduate from San Francisco. After receiving his law degree in 1963, Leon Panetta enlisted in the United States Army and was commissioned a second lieutenant. Assigned to Military Intelligence, he spent most of the next two years stationed at Fort Ord, not far from his family’s farm. He received the Army Commendation Medal for meritorious service and was discharged as a first lieutenant in 1966.

At the time, Leon Panetta identified with the liberal wing of the Republican Party, associated with Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York and with a number of California statesmen, including Chief Justice Earl Warren and Senator Thomas Kuchel. As assistant minority leader in the Senate, Senator Kuchel worked with President Lyndon Johnson and senators from both sides of the aisle to win passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Pursuing his interest in public service, Panetta joined the staff of Senator Kuchel as a legislative assistant. On Kuchel’s staff, Leon Panetta acquired expertise in the emerging body of civil rights law. In 1968, the senator, at odds with the increasingly conservative direction of California Republicans, lost his party’s primary.

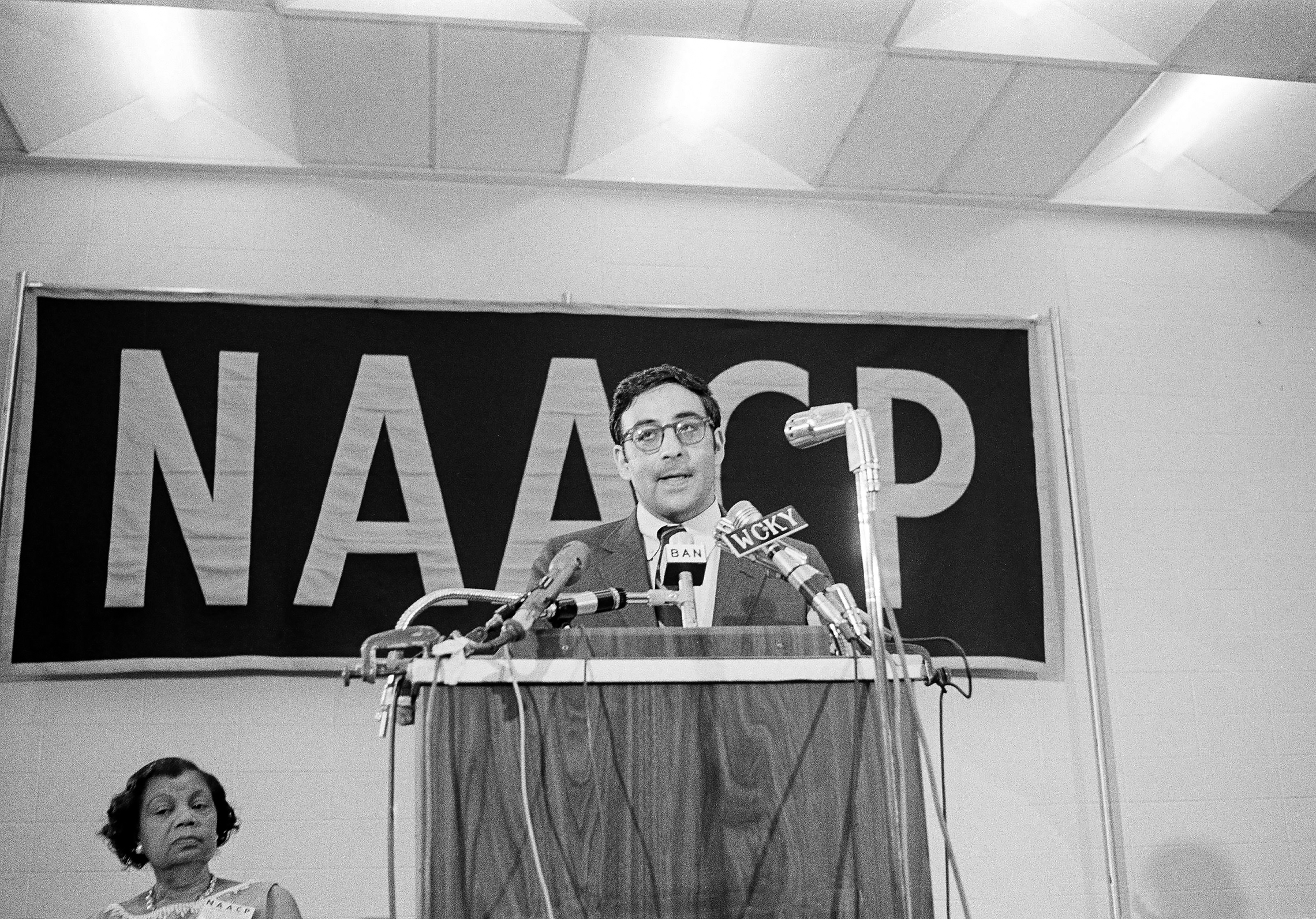

A California ally of Senator Kuchel’s, Lt. Governor Robert Finch, was named to serve as Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare in the incoming administration of President Richard Nixon. Finch invited Panetta to join the department and placed him in charge of the Office of Civil Rights. Panetta was eager to set about the work of desegregating the nation’s schools, but President Nixon had promised a number of Southern leaders that, in exchange for their support, his administration would ease up on enforcement of the civil rights laws and the desegregation of public schools. Panetta continued to enforce the law despite increasing pressure from his superiors. Little more than a year after taking office, he was informed indirectly that he had “resigned” his office.

With a growing family to support, Panetta was unsure of his future in politics. He joined the administration of New York City Mayor John Lindsay, another liberal Republican. Both Lindsay and Panetta became frustrated with the Republican Party’s increasingly conservative direction and eventually re-registered as Democrats. Returning to California, Panetta practiced law in Monterey and wrote a book about his experience in the Nixon administration, Bring Us Together: The Nixon Team’s Retreat from Civil Rights (1971). Panetta’s book and his principled stand on school desegregation drew national attention. After a few years of practicing law in Monterey, he won election to Congress, representing the Monterey Bay area in Washington.

In Congress, Panetta applied himself to mastering the details of the massive and complex federal budget. He earned a reputation for hard work, honesty, and willingness to look beyond partisan disputes to pursue the common good. Sylvia Panetta oversaw the local offices in his congressional district, where he remained popular and was repeatedly re-elected. In addition to his interest in civil rights and fiscal policy, he became a champion of environmental issues vital to his native region, protecting the California coastline from oil drilling and writing legislation that created the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. He also assisted in the establishment of California State University, Monterey Bay, located at the former site of Fort Ord, the army base where he had spent his own years in uniform. Congressman Panetta wrote the Hunger Protection Act of 1988 and the following year became chairman of the House Committee on the Budget. Throughout his eight full terms in Congress, Panetta combined commitment to education and healthcare with a commitment to securing the nation’s finances.

Leon Panetta was elected to a ninth term in Congress in 1992, but after a presidential campaign in which the country’s ever-growing budget deficits had been a major issue, President-elect Bill Clinton called on the Californian to head the White House Office of Management and the Budget (OMB). As OMB director, Panetta helped draft the president’s first budget proposal to Congress. The budget increased taxes on the most affluent while continuing the previous administration’s policy of reducing defense expenditures to reflect the changing priorities of the post-Cold War era. On this basis, each year’s budget ran a progressively smaller deficit. Panetta’s work had laid the groundwork for a future balanced budget. Panetta’s integrity and administrative skills made a profound impression on the new president and his inner circle. In 1994, Leon Panetta was named White House Chief of Staff, tasked with imposing order on a White House operation that had grown increasingly chaotic.

As Chief of Staff, Panetta became a principal negotiator with the Republican-led Congress. The budget of 1996 continued the administration’s progress toward the first balanced budget in nearly 30 years. With revenues increasing and expenditures held in check, the federal budget of 1998 saw income finally exceed expenditure. The federal government ran a surplus for the remaining years of the Clinton administration.

Panetta stayed with the Clinton administration through the president’s successful re-election campaign of 1996 and then returned to California. He and his wife, Sylvia, founded the Panetta Institute for Public Policy. Based on the campus of Cal State Monterey, the Institute provides a variety of study opportunities in government, politics, and public policy throughout the California State University system, including a lecture series, research archives and fellowships, legislative internships, and leadership seminars.

No longer in public office, Leon Panetta remained a sought-after authority on public affairs. In 2006, with the administration of President George W. Bush mired in a frustrating occupation and counterinsurgency operation in Iraq, Panetta was asked to join former Secretary of State James Baker and former House Foreign Affairs Chairman Lee Hamilton in the Iraq Study Group, to review policy in the region and consider alternatives to the current policy.

In the closing months of 2008, President-elect Barack Obama asked Leon Panetta to serve as director of the CIA. Trust in the agency had eroded following the terror attacks of September 11, 2001 and the subsequent war in Iraq. In both cases, public opinion faulted the intelligence agency — for not cooperating with domestic law enforcement to prevent the September 11th attacks and for justifying the invasion of Iraq on the mistaken assumption that Iraq was concealing weapons of mass destruction.

Panetta was uncertain that his two years of service as an intelligence officer more than 40 years earlier qualified him for this position, but President Obama believed that an outsider was needed to restore the agency’s credibility. As CIA director, Panetta placed a priority on the capture or elimination of Osama bin Laden, leader of the terrorist group Al-Qaeda, responsible for the 2001 attacks on America. Early in his tenure, the agency suffered a horrible loss when seven CIA officers, following a lead on bin Laden’s whereabouts, were killed by a suicide bomber in Afghanistan. Panetta redoubled efforts to locate the terrorist leader.

As CIA director, Panetta’s efficiency and determination were praised by agency staff and others in the national security community. In April 2011, President Obama nominated Panetta to serve as Secretary of Defense, but Panetta had an unfinished job to complete at the CIA. Analysts had identified a compound in Pakistan that Panetta and others suspected was bin Laden’s hiding place. On May 2, 2011, a Navy SEAL team, operating on CIA intelligence, attacked the compound and bin Laden was killed in the ensuing firefight. Leon Panetta’s tenure at the CIA ended on a note of triumph, and his nomination as Secretary of Defense was approved by all 100 members of the United States Senate.

At the CIA, Panetta had extended spousal benefits to the same-sex partners of its LGBT employees. At the Pentagon, he joined the Joint Chiefs of Staff in certifying the end of the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy which had required gay service personnel to conceal their sexual identities. As OMB director in the 1990s, Panetta had taken the end of the Cold War as an opportunity to reduce defense spending and balance the federal budget. But in 2011, with the country engaged in armed conflicts in both Iraq and Afghanistan, Panetta asserted that further cuts would hamper the nation’s ability to deter threats from China, North Korea, and Iran. Panetta considered the possible acquisition of nuclear weapons by Iran to be an unacceptable threat to the peace of the world. In planning a 21st-century defense strategy, he also proposed reforms to the military pension and healthcare systems. In one of his last acts as secretary of defense, he directed all branches of the military to determine which jobs were not open to women and to produce timetables for integrating women into every area of the service.

Leon Panetta retired from the Department of Defense in 2013 and returned to California to direct the Panetta Institute with his wife, Sylvia. He also serves on the boards of the New York Stock Exchange, the Oracle Corporation and the insurance company Blue Shield of California. He reviewed his long political career, and his policy successes as well as his disagreements with the presidents he served, in his 2014 memoir, Worthy Fights. Leon and Sylvia Panetta make their home on the family walnut ranch in Carmel Valley. The youngest of their three sons, Jimmy Panetta, was elected to the House of Representatives in 2016, representing virtually the same area his father was elected to serve 40 years before.

In an era of bitter political partisanship, Leon Panetta is the rare public servant who enjoys unqualified respect from leaders of both parties. Born in Monterey, California to Italian immigrant parents who operated a restaurant, and later a farm of their own, he earned his law degree from Santa Clara University and served as an intelligence officer in the United States Army.

In 1970, he was forced to resign his post as head of the Nixon administration’s Civil Rights Office when he would not yield to White House interference in his efforts to enforce the civil rights laws. A Republican, he eventually switched parties and won election to the U.S. Congress as a Democrat. Panetta represented the Monterey Bay area in Congress for 16 years, acquiring formidable expertise in the government’s finances as chairman of the House Budget Committee. As director of the White House Office of Management and Budget under President Clinton, he helped craft the plan that set the federal government on the path to its first balanced budget in over 25 years. As the president’s chief of staff, he negotiated the historic compromise with a Republican-led Congress that created record budget surpluses.

Tapped to serve as director of the CIA by President Obama, Panetta oversaw planning for the operation that eliminated terrorist leader Osama bin Laden. When the president selected Panetta to serve as secretary of defense, all 100 members of the United States Senate voted to confirm his nomination.

You were director of the CIA during the planning of the raid that killed Osama bin Laden. Can you take us back to those days? What was it like?

One of the things the president made clear is that we really did have to go after bin Laden, and I remember sitting down with people at the CIA and saying, “Where the hell is this guy? It’s been over ten years!” And they said, “Every clue we’ve gone after, every lead we’ve gone after, has led nowhere. We don’t know where he is. He could be in a cave. He could be anywhere.”

And I said, “Look, we’re going to form a task force, and we are really going to focus on developing ideas as to how we can get to bin Laden.” And I really was tough on them. The old “you’ve got to beat them up to make sure they’re doing the job.” Our goal was to go after bin Laden. I said, “I want you to come in and brief me every week as to what’s going on, and I do not want you to come into this room and tell me we don’t have anything. That’s unacceptable. I expect you to come in here, and if you don’t have anything, I want five new ideas about how we can try to locate him.” So they did, to their credit. They came up with all kinds of ideas.

We finally had a great lead, which was the couriers to bin Laden. We were able to identify who they were. We identified their faces. And we actually found them in a town called Peshawar and tracked them from Peshawar in Pakistan to a place called Abbottabad, where we found this compound. And once we saw the compound, we knew something was up. This was a compound that was three times the size of other compounds, had 18-foot walls on one side, 12-foot walls on another side, barbed wire at the top. We knew there was high security there. We identified a family — that there was a family living on the third floor that resembled a lot of the members of the family of bin Laden. And so we really thought we had a great breakthrough.

The president says we really should conduct this operation. We’ve decided on using the SEALs — a commando raid. Two teams of SEALs, two helicopters going in, 150 miles, at night, into Pakistan to go after this compound. It was a hell of a mission and very risky. And frankly, when we were in the National Security Council, a majority of the people on the National Security Council thought it was too risky. I thought that we should do it. I recommended that to the president, and the president, to his credit, made the decision to go. So I’m at CIA. We are conducting the operation from CIA because it’s a covert operation. I’m in charge. Bill McRaven, who is head of Special Forces, is located in Afghanistan, and he’s tracking it from there.

The helicopters go in. We track them into the compound and then something happens that — it’s one of those nightmares that you wonder if it’s going to screw up everything. One of the helicopters goes down. It had been hot that day and heat from the ground stalled one of the engines. But to the credit of that pilot, he was able to set down the helicopter. The tail was up on a wall. And I remember saying to McRaven, “What the hell’s going on?” He said, “Don’t worry.” He was cool as a cucumber. He said, “Don’t worry. I’ve got a backup helicopter coming in. Our Special Forces are going to go in. They’re going to breach the walls. They’re going to keep going with the mission.” And I said, “God bless you. Let’s get it done.” There was a moment of silence — actually, almost 20 minutes of silence. We heard gunfire at the beginning of that.

We don’t know exactly what’s happening. I know there’s gunfire. That tells you something. And then about 20 minutes later — it’s probably the longest 20 minutes of my life — McRaven comes back over the communications and says, “I think we have Geronimo.” Geronimo was the code word for locating bin Laden. We all kind of tensed up. There was a few more minutes — again, the longest in my life. And he comes back, and he said, “We have Geronimo,” which meant they had bin Laden. And they got bin Laden. They put him on the backup helicopter. They put all of the people back on the helicopters. They all got the hell out of there. They blew up the helicopter that was on the ground. That woke up the Pakistanis. We were worried that the Pakistanis might try to stop the helicopters, but they didn’t do that. We were able to get out in time. They made it back to Afghanistan, and I remember when the president made the announcement. And by the way, when I was at the White House, you could hear people outside the White House yelling, “USA! USA! CIA!” And I never forgot that. I thought that was just a moment where America really felt good about what had happened. And look, the fact is we sent a message to the world that nobody attacks the United States and gets away with it.

What were you thinking when you heard we got him?

Leon Panetta: It was all of the work by all of those people involved in the CIA and in Special Forces, all of the sacrifice, all of the risks that were taken in order to do that mission. I suddenly felt all of this has really paid off. And you know what, it was a moment when I thought about the victims of 9/11 and their families. I really felt that those families are going to embrace this moment probably more than anyone else because we will have gotten the individual who killed their family member.

Few people have had as long and distinguished a career in public service as you have: member of Congress, White House chief of staff, head of the CIA, defense secretary. How did you first become interested in public service?

Leon Panetta: Well, there wasn’t a lightning bolt. I wasn’t Saint Paul suddenly getting a lightning bolt out of the sky. It was really something that grew on me for several reasons.

I’m the son of immigrants — Italian immigrants. And my parents used to always emphasize that it was important to give back to the country because of what the country had given them. I used to ask my father why he came all of that distance to this country, leaving family. It was a poor area of Italy, but he had family, he had people that he related to back there. Why would you do that? And I never forgot his response, which was that “The reason your mother and I came here is because we really believed we could give our children a better life,” which, in many ways, is the American Dream. So because of what this country gave them in terms of the opportunity to work hard and succeed and give their children a better life, they used to always emphasize the importance of giving back to the country.

When I served as a lieutenant in the Army, the experience of working with a broad cross-section of people from across the country — and that was the case in those days because of the draft. You had people from everywhere across the country that were part of the military — and the experience of working with them and finding that you really could come together on a common mission, in terms of duty to the country and accomplishing that mission and working together as a team, that really inspired me about the importance of really being able to work together to achieve a mission. And then, lastly, you know, John Kennedy as president, a young president, who said, “Ask not what your country can do for you but what you can do for your country.” That was really an inspiration. At that time, public service was really a higher calling, and I really felt that way.

We’d like to ask about your grandfather. He was from Italy and lived with your family. What happened to him during World War II?

Leon Panetta: Yeah, I was very close to my nonno. That’s what we called grandfathers in Italian: my nonno and nonna. And my grandfather had come over in 1938. My grandfather was a big guy. He was over six feet. He had been in the Merchant Marines, and he sailed around the world in the old sailing ships. I remember now, when I went to Australia as CIA director and secretary of defense — and going to Sydney — that my grandfather used to talk about how beautiful Sydney was, and he went there in the old sailing ships and came to Monterey to visit my mother. He actually did some fishing in Monterey.

And then the war broke out, and my grandfather was not allowed to go back to Italy. So the one thing he did — because both my parents were working in the restaurant; my father was the chef and my mother handled the cash register — and so my grandfather basically took care of me and my brother. My brother was a little older, so he was out running around in the neighborhood. We were in an Italian neighborhood, so everybody kind of took care of each other. But my nonno really took care of me. And he used to walk with me. He used to put me on his shoulders, and we’d go down to the ocean together. And then suddenly, because of the war, a decision was made that, because he was an alien and he wasn’t a U.S. citizen — it sounds a lot like the problems we’re having today — there was a decision made that he might be a threat to national security, and aliens like him might be a threat to national security, so that they were required to move inland. Now, they didn’t set up camps like they did for the Japanese, thank God. But the fact was that my grandfather had to move away from the family because of that requirement. And I was asking myself, as a young boy who loved my grandfather, my nonno, I said, “Why is this happening?” And my parents really didn’t have a good explanation. They were trying to figure it out as well. But I do remember driving with them and my grandfather to San José. And we were able to locate a boarding house in San José, where a lot of other Italians had to move to, and leaving him. And I can’t tell you the impact that that had on me as a young boy, leaving my nonno.

I never forgot that experience. I guess it’s the first time, as a young boy, that you experience that something’s not right — that in this country, where you’re kind of growing up and enjoying life and going to school, and you have kids that you grow up with, you don’t really think about whether you’re different. The great thing about America, frankly, is that we all grow up together — but then suddenly, when something like that happens, not because there is any kind of security justification here, but it’s because you’re Italian and you’re an alien. It’s what happened with the Japanese, obviously.

Are we making similar mistakes now?

Leon Panetta: Yeah, I think we are. We are, I deeply believe — and it’s not only because I’m the son of immigrants, but I think we’re a land of immigrants. America’s a land of immigrants. I mean, my God, our forefathers were immigrants to this country. The pioneers were immigrants. We had immigrations from across the world.

What upsets you the most about what’s going on now?

Leon Panetta: I think it is kind of turning our traditions and our legacies and our values on their head.

Our fundamental value in this country is that we respect people because of who they are. There is a dignity associated with people, no matter where the hell they come from — whether they come from Italy or Ireland or Germany or Asia or Africa. Wherever the hell they come from, they’re human beings, and they deserve our respect, and they deserve the dignity of being a human being. And America has been great about that. We are a country that has welcomed immigrants. And it’s what’s made us strong. We are a strong country because of immigrants who have come to this country and now claim America as their land. We’re strong because of that. That’s what the Statue of Liberty is all about.

The Statue of Liberty basically makes the point that we are a nation that welcomes people to this country. And now my fear is that we’ve kind of turned that around. We’ve turned that on its head. Suddenly the values that I thought were so important to what makes America a strong country, we’re beginning, at the highest levels, to reject some of those values. I think that’s a bad mistake.

Are you talking about the travel ban on some Muslim countries, or the position on “dreamers,” the young people who were brought here as children?

Leon Panetta: I’m talking about the travel ban. I’m talking about DACA and these young kids. They’re not guilty of anything. Maybe their parents did come here in an undocumented way, but why should the children, who are innocent, bear the penalties for the sins of their parents? That’s crazy. These kids are getting an education. They’re growing up in this country. They’re getting jobs. We have those kids in the military, who are serving in the U.S. Army, and they’re putting their lives on the line for this country. Are we suddenly going to make the decision to deport these kids? That’s crazy. That’s not what America’s all about.

You started your career in government as a Republican. You headed the Civil Rights Office in the Nixon administration. How did you learn that you no longer had that job?

Because of the experiences we just talked about, I really got very interested in civil rights when I got out of the Army and went back to work for a U.S. senator from California, Tom Kuchel, who was a kind of progressive Republican. He came out of what we call the Hiram Johnson tradition, which was a progressive Republicanism reflected in people like Kuchel and Earl Warren and many others. And that’s what I was. I was basically a kind of progressive Republican. So I went back, and Kuchel was working with a lot of other progressive Republicans, people like (Jacob) Javits from New York, and (Clifford) Case from New Jersey, and a number of others. And they were working with Lyndon Johnson and Democrats on civil rights legislation. And I was asked by the senator to kind of staff him on that issue. So I worked on civil rights legislation, and we were able to pass some landmark bills as a result of that.

So when Kuchel was defeated in a primary, and I’m looking for a job or deciding whether to come back to Monterey, I was offered a job in the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare by Bob Finch, who was another moderate Republican, who became secretary of HEW in the Nixon administration. Because of my work on civil rights, I ultimately became director of the Office for Civil Rights, enforcing civil rights laws, particularly with regards to education, equal education. And a big focus of that obviously was on the South because children had been divided by race for almost 200 years. Black kids went to black schools, and white kids went to white schools, and that’s what Brown vs. the Board of Education was all about, was the decision that a separate education is inherently unequal.

I was required, as director of the Office for Civil Rights, to go into these school districts and make sure that they were breaking down the dual school system and taking steps to desegregate these schools. And we were making good progress. The problem was that Nixon had cut a deal with the South in what was called the “Southern strategy.”

He was worried about Rockefeller when he was running for president — Nelson Rockefeller, who was a moderate Republican. So he cut a deal with a lot of the Southerners that he would back off of tough civil rights enforcement. They supported him. It’s called the “Southern strategy.” I was aware of that, but I really did not believe, when I became director of the Office for Civil Rights, that we would retreat on an issue as fundamental as whether or not we give children — young children — the right to an equal education.

And also because Nixon himself had supported civil rights when he was in the Congress, when he was a senator. And he’s a Quaker, by religion. They believe in civil rights. So I thought, you know, “It’s going to be tough. We have this political deal, but at the same time, I think enforcing civil rights laws is the right thing to do.” So I was doing that. I knew there were political pressures to back off, but I continued to do it. And I kind of made that a very fundamental decision.

I tell the students here at the Panetta Institute: “You may face this decision, which is a decision between whether you do what you believe is right — whether you do something that abides by your conscience — or whether you make the decision that you’re not going to abide by what’s right because you can advance your career.” A pretty fundamental decision that I think a lot of people have to face, and you have to decide, “What course do I take?”

I remember talking to my wife about that, that I was worried that I was getting a lot of pressure, and I didn’t know whether it was going to result in my getting fired or whether I should capitulate. And I made the basic decision, “No, I’m going to stick to what I think is right. I worked on this legislation. I believe it’s right. I’ve got to do what’s right.” Now, part of that is the Jesuits at Santa Clara, who taught me about right and wrong. But part of it was just that gut feeling.

I remember Tom Kuchel saying to me when I first went back as a legislative assistant — he brought me into the room, and we were just a couple of us. And he said, “You guys are going to be tempted. Understand that. This town tries to go at you to try to impact on my vote. But I want you to remember that we’re here to protect the rights of the American people and the rights of the people of California. And I also want you to remember one thing: when you get up in the morning, you have to look at yourself in the mirror.”

So what happened to your job with the Nixon administration?

Leon Panetta: Remembering what Kuchel said, that you got to wake up in the morning and look at yourself in the mirror, which is about integrity, I continued to enforce it.

One morning, a newspaper lands at the door, and we open it up, and there’s an article that said, “Panetta has resigned as director of the Office for Civil Rights.” I hadn’t resigned, but that was what the article said. There had been some articles about some speculation about whether or not I would be fired because of civil rights, et cetera. But we continued to reject it. So I remember going to work, going to visit the secretary, Bob Finch, and saying, ”Bob, there’s an article in the morning paper that says I resigned, and we’re denying it because I haven’t resigned.” And he said, “Oh no, that’s the right thing to do. Keep denying it. It’s just one of these rumors that are out there.” I said, Fine.” So I continued to do my work. But then they had, as they do now, a press conference, daily press conference, with the press secretary to the president. It was Ron Ziegler at the time, working for Richard Nixon. Ziegler was asked, “What about this article that says Panetta has resigned?” And Ziegler said, “That’s correct; he has resigned.” And I looked at that, and I said, “What the hell? This basically means I’m fired.”

What impact did that have on you?

Leon Panetta: Well, I think I was only about 27 or 28 at the time. You can see your political career going up in smoke, but more importantly, you also worry about your family. We had two kids. I think we had a third child on the way. So you worry about that. But at the same time, I remember getting up at a press conference at the time and saying, yes, I’d submitted my resignation, but I really wanted to urge the administration to continue the good work on civil rights enforcement.

Do you think the country’s attitude towards public service has changed since you began your career?

Leon Panetta: I think it has changed. I think that it’s the reason we have this Institute for Public Policy, is because we’re concerned about young people being inspired to give back to the country, to provide public service. Our democracy depends on that. So I’ve always felt that our obligation as citizens of this country is to give something back to the country and to do everything you can to make sure that our democracy is strong, particularly in order to give our children that better life. I think that’s what public service, frankly, is all about. It’s about the American Dream. It’s about giving people a better life.