I decided quite subconsciously that I was going to prove to my dad that I had real worth and could do something, but the only language he understood was his business. I thought ‘his business was wrong. I’m going to do one that’s right’ and invented one in my mind and began making sketches of stores.

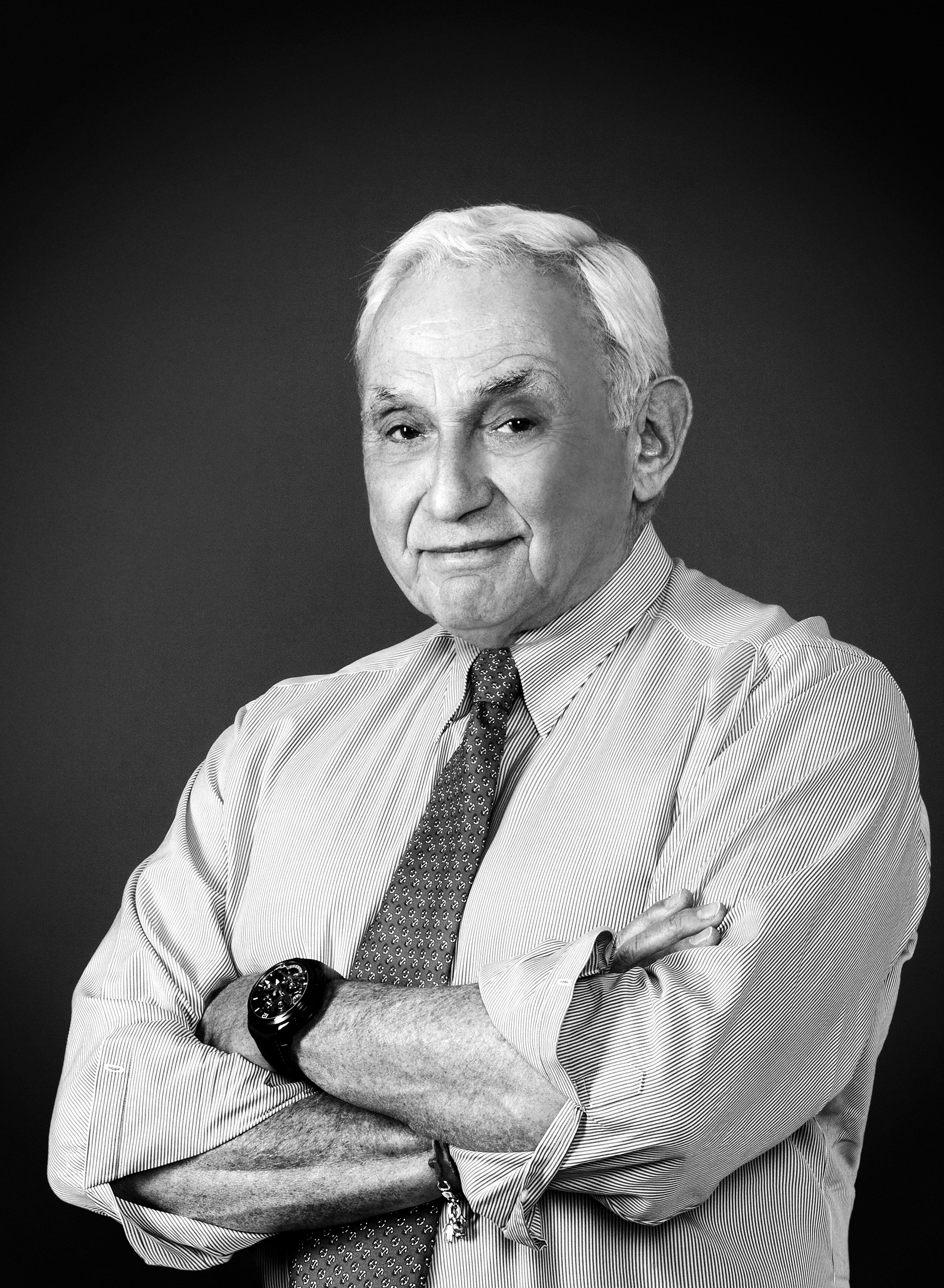

Leslie H. Wexner was born in Dayton, Ohio. His parents, Harry and Bella Wexner, were both of Russian-Jewish origin. His father was born in Russia; his mother was the first member of her immigrant family to be born in the United States. After working for a number of major department stores, the elder Wexners opened a small clothing store of their own in Columbus, Ohio. The couple named the store Leslie’s, for their son. From an early age, Wexner’s parents treated him like an adult, asking his advice and including him in family business discussions.

Young Leslie showed an entrepreneurial streak from an early age, organizing other local boys to join him in a lawn mowing business and other small ventures. He was encouraged to study hard although he enjoyed school less than his outside enterprises. He graduated from Ohio State University with a business degree and served in the Air National Guard before returning to Columbus to consider his career options.

After a brief experience of law school failed to ignite his passion, he agreed to assist his parents in their store and learn more about their business. Profit margins were small and the family could afford few luxuries. When his parents took a brief vacation — their first — and harsh weather kept the customers away, young Leslie carefully reviewed his parents’ books and made an interesting discovery. Large-ticket items, such as winter coats, that the elder Wexners believed were the most important, were actually yielding little profit, while lower-priced items that turned over quickly were the actual profit center of the business.

Leslie tried to share his findings with his father but was unable to persuade him to change the family’s business model. Instead, Leslie Wexner set out to start a business of his own. An aunt offered him the use of $5,000 — an open-ended interest-free loan — as collateral. Borrowing from the bank against the money his aunt had given him, he planned to open a small clothing store in a rented space between a supermarket and a dry cleaner. When a new shopping center was built in the nearby suburb of Upper Arlington, he decided to rent that space as well and open two locations at once. With only the original $5,000 in the bank, he had soon taken on commitments of nearly a million dollars.

Wexner decided to narrow his focus by concentrating solely on clothing for younger women, the age group whose taste he knew best. Seeking a novel identity for his business, he called his stores The Limited and opened his doors for business in 1963. Wexner possessed a sixth sense for the tastes of his customer base. Success came quickly, and within a year his parents closed their old store to come work with him. Slowly and methodically, he expanded his business in concentric circles from locations he could personally visit in the course of a day. Within a few years, he expanded from the Midwest to both coasts. By age 30, Les Wexner was a rich man.

In 1969, The Limited made its debut as a publicly traded company. The chain prospered throughout the 1970s, and Wexner began to consider other opportunities for expansion. Knowing his customers’ tastes as he did, he suspected that there was an unmet demand for stylish intimate apparel. He was in San Francisco opening a new location for The Limited when his employees drew his attention to an unusual little lingerie shop nearby.

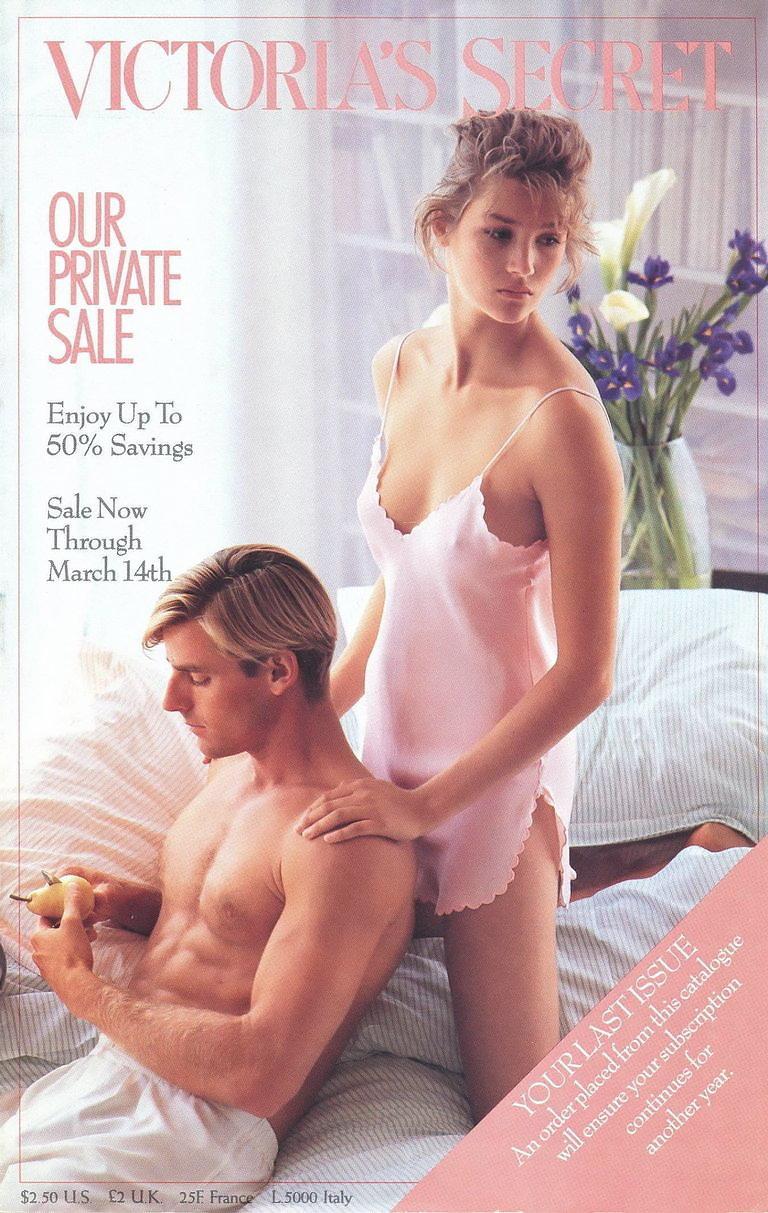

Founded by Roy Raymond in 1977, Victoria’s Secret had grown to a handful of stores in the San Francisco Bay Area when Les Wexner first visited the chain’s San Francisco location. Wexner was intrigued by the store’s eccentric Victorian atmosphere, but the owner declined to meet with him. Within a year of Wexner’s first visit, though, Victoria’s Secret was in serious financial trouble and Raymond offered to sell Wexner the business. The Limited purchased Victoria’s Secret for $1 million.

Doubling down on this gamble, Wexner also bought out the Lane Bryant stores, adding them to the growing Limited family of companies — along with a single Henri Bendel store — purchased for $10 million; and, in 1985, 798 Lerner dress shops were acquired for $297 million. In 1988, The Limited purchased 25 Abercrombie and Fitch stores for $46 million, later spinning them off as a publicly traded company in 1996.

While Raymond had built the first Victoria’s Secret stores on the assumption that his primary customers would be men buying lingerie as gifts for the women in their lives, Wexner reversed the assumption and geared his stores toward the female shopper. Inspired by Emile Zola’s 1883 novel, The Ladies’ Paradise, he sought to make his stores a stress-free haven for women to buy intimate apparel in comfort and privacy. He continued Raymond’s practice of printing a mail order catalogue to drive sales as well. In the first five years of his management, Wexner grew Victoria’s Secret from a handful of stores in the San Francisco Bay Area to nearly 350 locations across the United States. As the only national chain specializing in lingerie, it drew market share away from traditional department stores. In a single year, 1990, sales quadrupled. In 1995, Wexner initiated an annual Victoria’s Secret fashion show, broadcast on primetime television.

In the 1990s, the chain was among the first to make use of sophisticated data analysis to determine which products sold best in given locations, increasing their sales by 30 percent. Meanwhile, Wexner sought to move beyond lingerie into bath products and cosmetics. In 1990, L Brands opened its first Bath & Body Works store in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Specializing in shower gels, lotions, fragrance mists, perfumes, candles, and home fragrances, by 1997 it was the largest bath shop chain in the United States. That year, Wexner launched a secondary brand, Bath & Body Home, later rebranded as White Barn Candle Company.

By 2006, Victoria’s Secret’s 1,000 stores across the United States accounted for one third of all purchases in the intimate apparel industry, while Bath & Body Works reported net sales of $2.3 billion. Wexner resolved to consolidate the sprawling family of Limited companies. He sold the Abercrombie & Fitch, Lerner’s, Lane Bryant and Structure stores. In 2007, Wexner sold a 75 percent interest in Limited Stores and Express to Sun Capital Partners, the better to concentrate energy and resources on building Victoria’s Secret and Bath & Body Works. The remaining 25 percent of The Limited was sold to Sun Capital in 2010. Wexner reorganized the remaining companies as L Brands.

In the 21st century, L Brands made its first moves outside the United States, initially into Canada, then into the duty-free areas of major international airports. In 2012, it opened its first stores in the United Kingdom, growing quickly from two locations in London to 15 stores throughout the United Kingdom by 2016.

At Victoria’s Secret, Wexner responded to challenges from competitors with increased expenditure on television advertising, and introduced a line of cosmetics. The company continued to keep up with changing trends and the tastes of younger consumers, featuring sports bras for athletic wear and bralettes — bras without underwire — to be worn visibly. As of 2017, Bath & Body operates 1,600 stores in the United States, Canada, Peru, Chile and Kuwait. L Brands now operates Victoria’s Secret, Bath & Body Works, Pink, Henri Bendel, the White Barn Candle Company, and La Senza.

Despite his far-reaching national and international success, Leslie Wexner has always made his home in Ohio. He has long been the state’s wealthiest resident and leading benefactor of its institutions. Among the objects of his philanthropy are his alma mater, Ohio State University, and his family synagogue, Congregation Aguda Achim. In 1984 he created the Wexner Foundation to foster Jewish leadership. The foundation supports volunteer programs in North America, a graduate fellowship for rabbinical students, for aspiring cantors, and for scholarship in Jewish studies, as well as a fellowship for Israeli public officials to study at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. In 1989, Wexner and his mother donated $1 million to the United Way, the largest personal donation made to the organization at that time.

In 1993, Leslie Wexner married attorney Abigail Koppel. The couple make their home in New Albany, Ohio, near Columbus. Their 335-acre estate hosts an annual equestrian competition to benefit the Center for Family Safety and Healing. The Invitational Grand Prix and Family Day draws the best show-jumping riders in the world. In 1997, the Wexners purchased the historic Foxcote House in Warwickshire, England. The same year, Wexner built a 315-foot yacht, the Limitless. At the time, it was the largest private yacht owned by any American; it remains one of the largest in the world. As of 2017, Leslie Wexner’s personal fortune was estimated at nearly $6 billion.

Leslie Wexner was long a member of the Board of Trustees of Ohio State University and served as the board’s chairman from 2009 to 2012. In 2011, he made a donation of $100 million to Ohio State — the largest donation in the university’s history — funding a Wexner Center for the Arts and supporting a massive expansion of the university’s medical center. Today it is known as Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center.

Wexner received unwelcome press attention in 2019 over his past financial ties to convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein, who committed suicide while awaiting trial on additional charges. Accusations of sexual harassment and discrimination at Victoria’s Secret coincided with the closure of several Victoria’s Secret stores and cancellation of the brand’s annual televised fashion show. Although many allegations focused on the conduct of another officer of the company, Wexner also came in for his share of criticism for his handling of the issue.

In 2020, Wexner, at age 82, stepped down as Chairman and CEO of L Brands. The company announced plans to sell a majority interest in Victoria’s Secret to private equity firm Sycamore Partners for a reported $525 million. Bath & Body Works will be spun off as a separate publicly traded company. Les Wexner continues to hold the title of Chairman Emeritus of L Brands.

As a young man, Leslie Wexner worked in his family’s small clothing store in Columbus, Ohio. Despite his parents’ long experience, Leslie believed he had a better idea for running a retail clothing business. While the then-dominant regional department stores — and neighborhood shops such as that of his parents — carried clothing for the entire family, Leslie Wexner decided to focus on high-turnover items for a single segment, young women. With a small loan from his aunt, he started a shop of his own — The Limited — and grew the business into a national chain.

Through ingenious innovation and strategic acquisitions, he built a family of enterprises, buying and selling companies such as Lane Bryant, and Abercrombie and Fitch. In 1982, he acquired a struggling San Francisco lingerie store called Victoria’s Secret for $1 million and built it into the world’s leader in intimate apparel. In time, Wexner buit L Brands — centered on Victoria’s Secret and Bath & Body Works — into a $12 billion international company, with more than 80,000 associates focused on lingerie, beauty and personal care products.

Wexner himself has long been the richest man in the state of Ohio, renowned for his generosity to local and national institutions. He is the leading benefactor of Ohio State University and a major benefactor of the Nationwide Children’s Hospital and the National Veterans Memorial and Museum in Columbus, as well as Harvard University’s Center for Public Leadership. Thanks to Leslie Wexner, thousands of men, women and children receive life-saving care every year at Ohio State’s Wexner Medical Center.

How did you come to open your first store?

Leslie Wexner: Mom and Dad had a neighborhood store. I had gone to law school. I really hated law school. In fact, I hated school generally. My dad said, “Why don’t you just hang around the store for a few months before you begin your life?” And I said, “Okay, what do you want?” and he said, “Well, if you hang around for a few months, you’ll learn how to open the store and close the store.” It was a little neighborhood store. It was like 15 feet wide, but that was the source of their income.

And I said okay. And he said, “Because after Christmas…” he said, “your mom and I would like to go on a vacation.” And he said, “You know, we’ve never had one.” And I said okay. He said, “I’ve never asked you for anything, but I would trust you to open and close the store and take the money to the bank.” You know, just do simple things. So I said okay. And they did take the week off in January. Columbus had a blizzard and their vacation was driving from Columbus to Miami, spending three days in Miami, and then driving back. So that was their big vacation after a lifetime.

And — kind of happenstance — had a blizzard in Columbus. I went to the store and there was like 18 inches of snow so there was no traffic, and I felt very obligated to be there, because I was kind of guarding the fort, and there was just nothing to do. So you know, you dust the floors, you’re prepared, but obviously no one’s going to come to the store.

I got bored, so I was curious to see what categories of merchandise my dad and mom made money in, and I could sort out the invoices, and they kept track of sales by category of merchandise, shirts and pants and skirts. I would look through the invoices to see, and I figured out that in what my dad called sportswear they were making substantial profits, and in the big ticket items — then dresses and coats — they were making no money.

When he came back from their vacation, we sat down in a Woolworth’s coffee shop and I gave him the big “ta-da,” and he said, “It’s impossible.” He said, “We make money on the big-ticket items.” I said, “No. You see them as big tickets, but you’re taking big markdowns and there’s no profitability.” And from that we got into a very classic father-son argument. So he’d say, “Go get a job! Your mom and I have struggled all our lives to have this small business and we’re going to run it the way we want to run it and you don’t know what you’re talking about.” And I said, “Dad, here’s the numbers. They don’t lie.”

Leslie Wexner: We had a number of arguments back and forth. He’d throw me out of the store and say, “Go home and go find a job.” I’d pout for a week or two and my mom would make peace with my dad. I’d go back to the store and he’d throw me out. As I look back at it, and didn’t see it at the time, it was a classic father-son kind of argument about merit and manhood or value.

I had decided quite subconsciously that I was going to prove to my dad that I had real worth and I could do something, but the only language he understood was the business he was in. So I thought “his business was wrong. I’m going to do one that’s right,” and I invented one in my mind and began playing with it and making sketches of stores and fixtures and thinking about things that I might sell.

I had a spinster aunt, and I don’t think she knew what was going on in terms of what I was imagining. She just knew that my dad and I weren’t getting along and I didn’t have a job. My Aunt Ida said, “I’ve got $5,000,” which was her whole net worth, a spinster aunt. And she said, “I’ll give you the $5,000, but you have to put it in the bank and promise not to spend it. But banks will loan money to people that have money, I think.” And she said, “So if I give you the 5,000, you put it in a savings account and you have to promise never to spend it because that’s all I have.” My parents couldn’t have contributed. They had nil.

So I did, waited a couple of months, and went to the neighborhood bank, and I said, “By the way, I’m thinking about starting a business,” and the loan officer at the branch said, “How much money do you have?” and I said, “Well, I’ve got $5,000 in your bank.” And he said, “Well, what do you want to do?” and I said, “Well, I don’t know, but I’ve got $5,000. Would you make me a loan?” And he says, “If you have 5,000, I’ll loan you ten, but why don’t you come up with an idea?” I said, “Oh.”

The store was successful, and by the time I was 30 years old, I was several times a millionaire. I knew it, but I can remember, just as an example, it wasn’t very important to me. I remember saying to my administrative assistant, “Do I have any money?” and she said, “Why do you ask?” and I said, “Because I want to buy a car.” And she said, “Well, of course you have money. How much do you want to spend on a car?” Maybe it was $3,000. “Yeah. No question. You could afford that.” So how I kept score was the growth of the business, but it wasn’t about score in terms of how much money I was making. I felt good about what I was doing. I knew I was employing people. I was growing the business. It was just tons of fun. It would probably be analogous to how an athlete would feel that just enjoys the sport and the fact that you get paid. I think Tiger Woods loves playing golf and he loves winning, and the fact that he got paid just made it all the better.

What is it about the retail game that you love?

Leslie Wexner: I think the retail game — I tell my kids this, I tell people that I’m recruiting — it’s just wonderful because it’s all about people. If you like accounting, you can do accounting. If you want to do money and banking, you can do money and banking. There’s a tasteful part that comes in the selection of merchandise, store design, systems design. So everything, all aspects of business come together in retailing.

And it’s really tough because it’s relentless. We’re not building jet engines, we’re guessing what young women are going to want to buy next week and three months from now. So the fickle fashion, the challenge of it, you have to be in the game every day because it’s changing. We don’t have a book of orders like GE does, making jet engines, and they design a new one every decade, and the order book lasts for three years and they’re managing to it.

How is it that this guy from Ohio was able to know what young women wanted to buy?

Leslie Wexner: I knew the young women I knew, and I knew what kind of clothes they bought, so I thought I would just buy clothes like I thought they would buy, and then they did. As I got older, still focusing on young women, I had to pay attention to what young women were buying and make guesses about what they would do. But I think the question about purpose — to get back to that — is to say, “Okay, you made a million dollars,” or you’ve made 10 million or maybe you could make 100 million, and I’d say, “Well, why? I’m just running this business. I started this business. It’s a ton of fun. Tons of fun for me. I really love what I do and I’m kind of racking up a financial score.” And it’s kind of, but why?

In those days, clothing retail was really a local business, but you built a national chain. How did that come about?

Leslie Wexner: I kind of backed into it. I opened the store and it was successful, and I said, if I had one, I probably could have two in the city. And if you have two in the city, you could have three. And I would think, “How many stores could you have?” If you could only have — let’s say the size of the market — the city of Columbus, I could have four stores.

So I said, “But if you went to two cities, you could have eight stores.” So that was kind of the amateur — the 27-year-old or 26-year-old — talking to himself. And I’d say, but people didn’t have stores in multiple cities. Department stores were locally owned. Specialty stores were locally owned. There were no regional or national businesses.

So I thought, when we lived in Chicago, my dad would commute an hour from the North Side to the South Side to work every day. It was an hour going and an hour coming. And I said, “Jeez, I could open a store in Dayton. It’s an hour to Dayton, an hour back. Dayton is kind of like Columbus. So if I lived in Chicago, I’d be commuting, so I’ll just commute to Dayton.” So that was the idea. I told my dad I was going to do that, and he said, “The merchants in Dayton will eat you alive. You’re lucky to be successful in Columbus.” I said, “Well, I think it’s the same and if the store doesn’t work, I could afford one failure.” And it worked.

The idea of leverage is like, if I had one store and I opened two; if you have two stores, how you could get to four? If you had four, could you get to eight? So I was just playing, just like scribbling on a napkin, and saying to you, “Is this pretty interesting?” But how do you get from one community, Columbus, if I’m going to get to a larger number of stores? I’d have to be in multiple cities.

Everybody knew that people didn’t have stores in multiple cities. And I said, “Well, I could try it.” Maybe I didn’t see it was leverage, but it was a way to get to scale, but I recognized — probably intuitively, couldn’t articulate it — we had a merchandise plan, we had a store design, we had a name of our store, we had a lot of things that were replicable. So if I could open a store, and then I could open another one just like it, and then you could open another one in another city just like it, calling it leverage, you have a replicable model that’s repeatable, and there’s also financial leverage and human scale.

So I recognize if I had four stores, then I’d probably have four assistant managers. Those four assistant managers have career opportunities to become store managers if I open more stores. If I’m picking a style for one store or a color of garment, why couldn’t I pick the same style for eight or ten stores? You’re just writing a bigger number. So what I tried to do is say, “What is what I’m doing? Could I copy it?” I really didn’t see it as leverage. It’s like McDonald’s building more golden arches. I could open more stores and I could try them in different cities and it kept expanding.

So Columbus and Dayton, then I said, “Well, Dayton is an hour away to drive and Milwaukee is an hour away to fly. I remember thinking, “What’s the difference between driving an hour to Dayton, or flying an hour to Dayton, or flying an hour to Milwaukee? It’s time and distance the same.” I got a map, and I said, “It’s far away, but the characteristics of Milwaukee, Columbus, Dayton are similar.” So you say, “Wow, that does work. You could actually open stores in Milwaukee. Then I went to an office supply store, got a map of the U.S., and got a compass and a wax crayon, and I drew concentric circles out 200, 300, 400 miles out of Columbus. And I said, “My God! Atlanta, New York!”

At that time, clothing sales were mostly in department stores, but you decided to focus on clothes for one segment, younger women. How did you decide to specialize?

When I started the business, I said, “What could I do?” and I said, “I don’t know very much.” So I probably heard this when I was in college, specialization was very popular. Friends that were going to be doctors weren’t going to be doctors, they were going to be dermatologists, they were going to be cardiologists. No one was just going to be a doctor.

So I was probably influenced by that and said, “I can’t compete with all these other guys, because they have more resources and they know a lot. So if I know a lot about a little, maybe I could find my way.” So that idea of being a specialist — businesses that are focused on young women and clothing and what they wear, and really knowing that customer and being very focused. I said, “Now I don’t have to compete with all the resources that let’s say a department store has. I’m just competing with one merchant.”

When you eventually decided to branch out, you could have chosen any area, but you chose intimate apparel and bought the Victoria’s Secret stores. Why lingerie?

The funny story I like telling is I was driving to Dayton to visit the store, and I was thinking about what other businesses I could start. I said, “Well, I don’t know anything about the shoe business. Half the people in the world are men. So maybe we could start a men’s business. I’m a man. Men don’t buy as much as women. But if our skill is in women, and stores and everything that women buy or wear.” You know? Shoes weren’t interesting. I didn’t think much about accessories then.

And I remember saying, “All the women I know wear underwear most of the time. All the women I know would like to wear lingerie all of the time.” And I’m just driving down the highway laughing my butt off and thinking what a funny thought that is. I’m driving back from Dayton and I’m laughing more to myself. “What does that mean? What’s the difference between lingerie and underwear?” Lingerie has emotional content. You know, men wear underwear, women wear underwear, but lingerie is… you know.

So I said, “I wonder why no one’s done that.” So I spent about two or three years as I was traveling around in Europe, Asia, department stores, specialty stores, and I said, “I can’t find a lingerie shop.” In my mind I said, “There must be this wonderful lingerie shop in Paris, or maybe in Zurich, or maybe in Berlin, or maybe in Vienna or just…” They don’t exist. And I said, “Wow!” So I had this imagination that there’s this wonderful lingerie store, except I can’t find one in Paris.

How did you first learn about Victoria’s Secret and decide to buy the business?

Leslie Wexner: We open a store in San Francisco. I’m there for the opening and pre-opening and design and setting up the store. And about a block away there’s a small lingerie store, and the ladies in the store say, “You have to go see it. It’s really kind of interesting.” I went down there and it was interesting. It was probably 800 square feet, and it was kind of Victorian. It was like velvet sofas and — it wasn’t Victorian from England. It was American Victorian. So it’s a Tiffany lampshades kind of a place.

But it was interesting, and I just never had seen anything like it, and I called the owner up. I said, “Gee, next time I’m in San Francisco, I’d like to meet you.” And he said, “What do you do?” and I told him I had the store down the street. And he said, “I don’t want to meet you because you just want to understand my secrets, and you’d probably want to start a business and put me out of business.” I said, “No, I’m just curious,” which I was.

And about a year later I get a phone call. The guy says, “This is Roy Raymond. Remember, we had the phone conversation?” I said, “Oh, yeah.” And he said, “Would you be interested in buying my business?” So it was his idea, not mine. I said, “I don’t know. I’ve been thinking about the lingerie business but we haven’t done anything. We’re very busy doing things.” And he said, “Well, if you want to buy it, you could buy it, but you have to come right away.” And I said, “Well, maybe I’ll be out in a week or two.” He said, “No, the sheriff’s going to shut me down tomorrow. So if you want to buy the business, you got to come out right now.”

So I said okay and just went out and met him. The first time I met him, he told me about his business. He’d started it as a master’s project, not unlike the way Fred Smith started Federal Express. And he was going broke. He said, “If you want to buy the business, here’s what I have and if we can come to an agreement, I’ll call the sheriff and tell him not to shut me down.”

What made you think you could make a success out of this? He was going broke.

Leslie Wexner: We knew how to run stores and he had no experience. This was a 3D real-life model of what he had written about in his master’s project while he was at Stanford. It makes sense that, you know, people buy lingerie. I didn’t know what the margin was. I didn’t know anything about it. I didn’t know about fits, constructions, all this stuff. I had to figure it out.

So I bought the business, and we were a public company, so I called our board, and I said, “I bought this business.” And the response was, “Well, everybody can have a toy. So if this is something you want to play with, it’s okay, but it could never be a business.” So that was kind of daunting, and we were very busy with other businesses.

So we said, “Roy, we won’t bother you. Here’s some cash so you can pay your bills. Just run the business and we’ll talk every three months.” I wasn’t much engaged. The real risky business is… You grow a business by starting a business, starting other businesses. You could buy a smaller business or you could acquire a larger business.

One Friday morning I was looking at the Wall Street Journal, and it said the management of a company called Lane Bryant was going to buy the company. And I thought, “Jeez, this is kind of interesting. If it’s a public company and the people that are running the company are going to buy the company…” And the article went on to say that the company had tried to sell itself and there weren’t any buyers so the management of the company decided they were going to buy it. Well, if that’s a good deal for them, it might be a good deal for us. Got some public information, called the president of the company and said, “We want to bid,” and he said, “I’m running the company and I’m a bidder…” So you know, “Fry ice.” We called their lawyer, who’s mentioned in the paper — the company lawyer. I said, “We’re real bidders.” And went to New York on a Friday afternoon, got a little bit of information about how many stores and how much business they had done, no financials. Met with Manufacturers Hanover Trust on a Saturday morning and arranged for a loan, bid on the company, and Monday night we owned it.

So I get home around three in the morning from New York and the net worth of our business was about $120 million. We borrowed $150 million from Manufacturers Hanover to buy Lane Bryant. The story was I get home, you know. I’m back at my house in Columbus. I go in the refrigerator. It’s three in the morning. Pour myself a big glass of white wine, and I remember looking in the window and seeing my reflection and sipping the wine and saying, “You just bet the ranch.” Six months later we paid off all the debt.

What gave you the confidence to bet the ranch?

Leslie Wexner: I was working with good people. We thought we had good business practices. We didn’t think they had very good practices, whether it was sourcing, how they ran stores, even how they collected cash from their stores, how they paid bills. I said, “I’ll just bet that they’re really screwed up and if we put our practices on their business, good things will happen.”

And how do you know when to get out of a business that’s not working?

Leslie Wexner: One of the things I’ve probably absorbed when I was in business school — and didn’t know I was learning it — was about life cycles, that things begin, and they peak, and then they decline. So whether you look at life cycles of fashion, or you look at life cycles of things that people buy, designs, everything is in a life cycle. So looking at things and saying, “Okay, where is this in the life cycle? Is it the beginning? Is it the harvest time? Or is this the part where it now becomes obsolete?” That thinking about the businesses that we’ve sold, it’s like my instinct. My thought was, it was about time in the life cycle, and move on. So getting out of the apparel businesses and into beauty and lingerie, those were very big bets, but they were very deliberately thought about and tested over time.

You modified the concept of Victoria’s Secret when you took over the stores. Where did you get that idea?

I like to know about people. I’m curious about leadership. I’m curious about biography and history, and reading biography from a historical point of view, and reading history to understand how people behaved. One of the things that influenced the business was Emile Zola’s book The Ladies’ Paradise. The notion of Victoria should be a ladies’ paradise. If men like Victoria’s Secret, that’s kind of a bonus, but in my imagination they should feel uncomfortable when they’re in the store, if there’s no mahogany paneling, there’s nothing that’s welcoming. This is a ladies’ paradise. And that thinking goes into the design of the store, the fitting rooms, the fabric, the display. It’s all from the lady’s point of view. It has nothing to do with men. Every so often somebody will say, “You know, if we had a men’s corner, we’ll have some nice Ralph Lauren wing chairs and a place where guys can feel comfortable when they’re in the store…” and I say, “No. This is a ladies’ paradise.” It’s all about her.

What surprised you the most about the success of Victoria’s Secret?

Leslie Wexner: I think probably it’s the universal appeal of lingerie. We’re selling the same things in Columbus, Ohio at the same time we’re selling them on Bond Street in London, Fifth Avenue in New York, and the Mall of the Emirates in Dubai, and in Hong Kong and in Shanghai. It’s the notion of sexuality, sensuality, how women feel about lingerie — it’s a universal thing. That’s surprising to me. Happily so.