I have always liked working in some scientific direction that nobody else is working in.

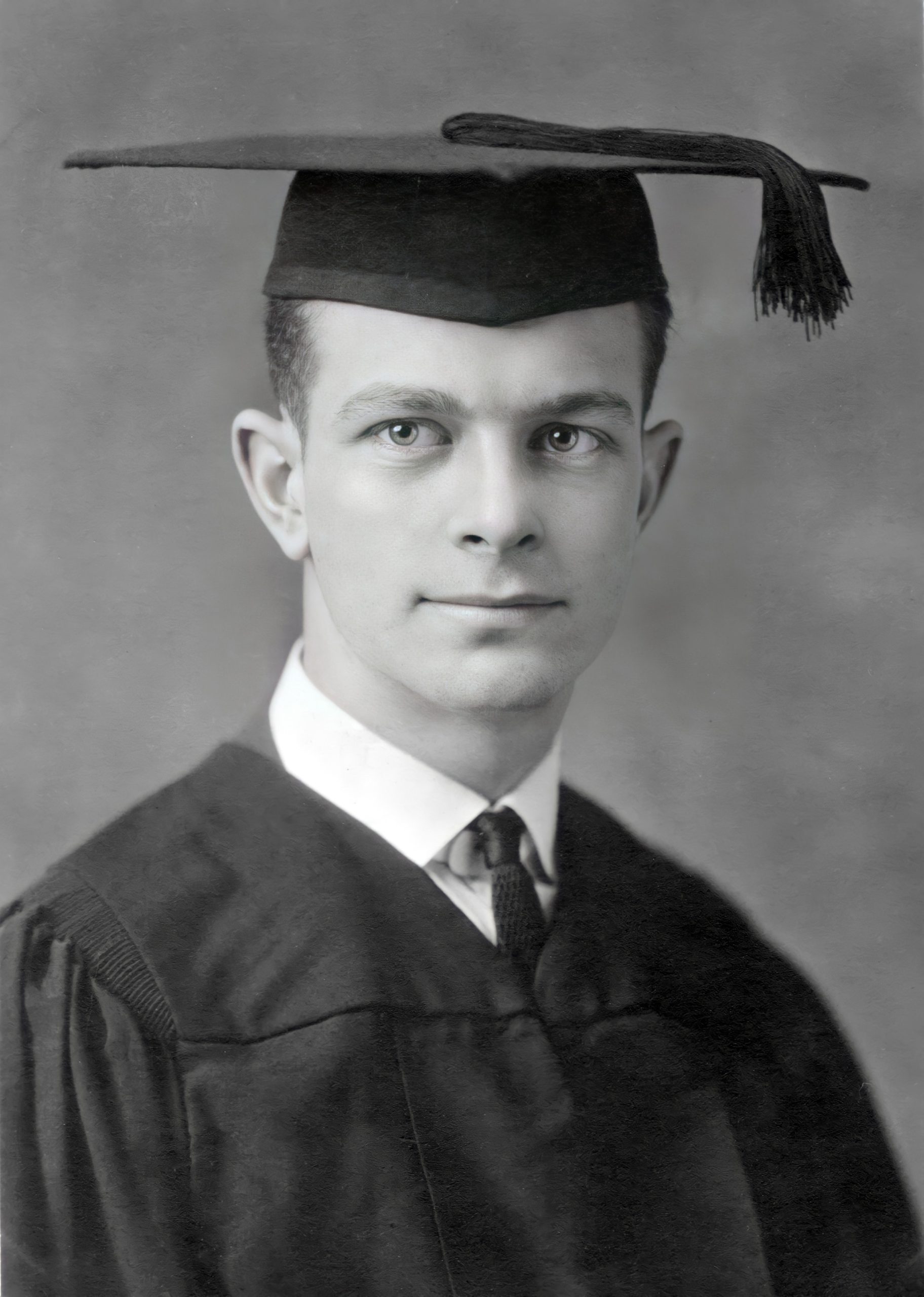

Linus Pauling was born in Portland, Oregon, where his parents encouraged his scientific interests from the beginning. When Linus’s father died, his mother found it difficult to support the large family. Linus was an able student and won scholarships to Oregon State University at Corvallis, but he had to work long hours as a laborer to support himself while he earned his Bachelor of Science degree. He went on to earn a Ph.D. in chemistry at the California Institute of Technology, the institution where he taught and carried out his research for the next 33 years.

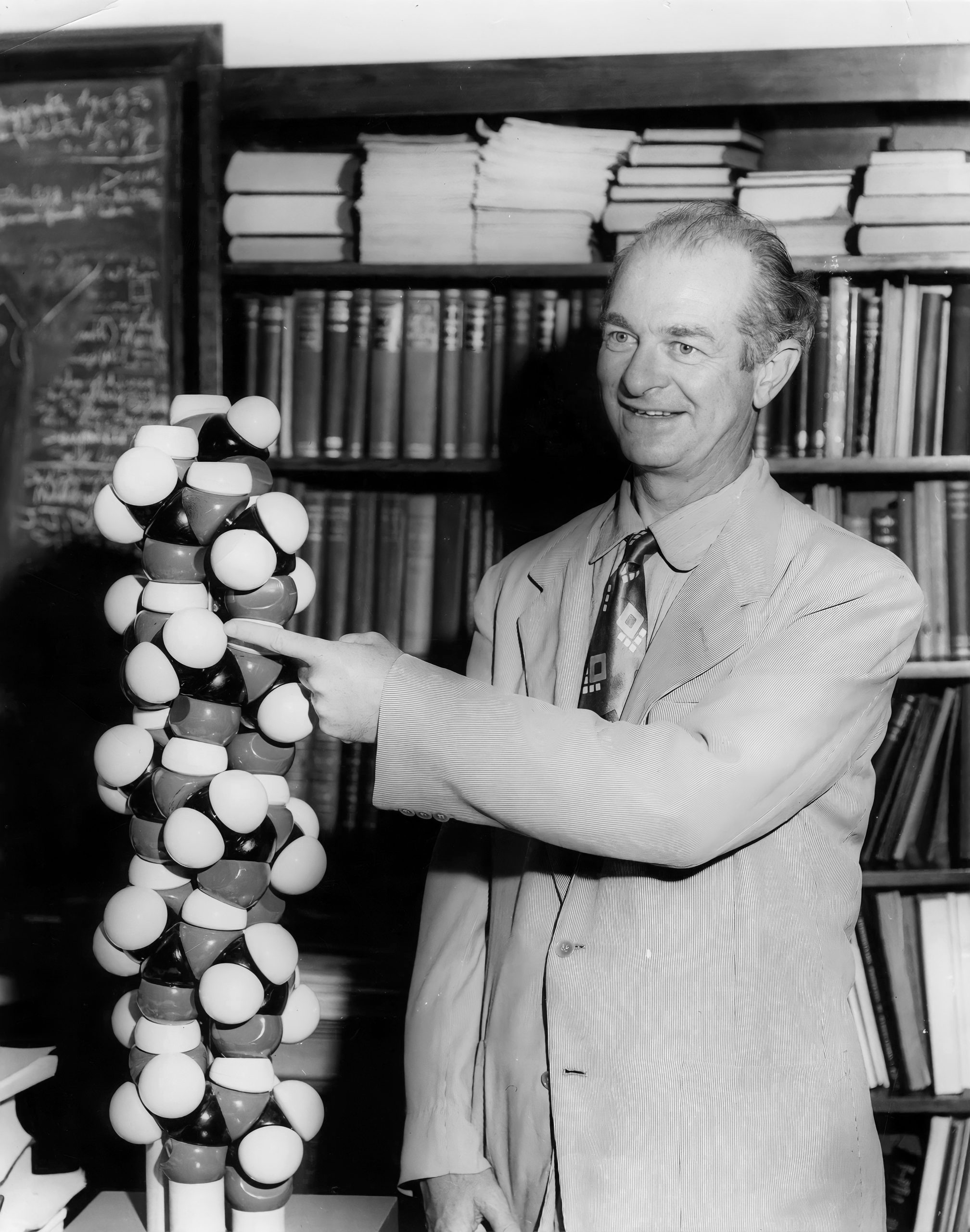

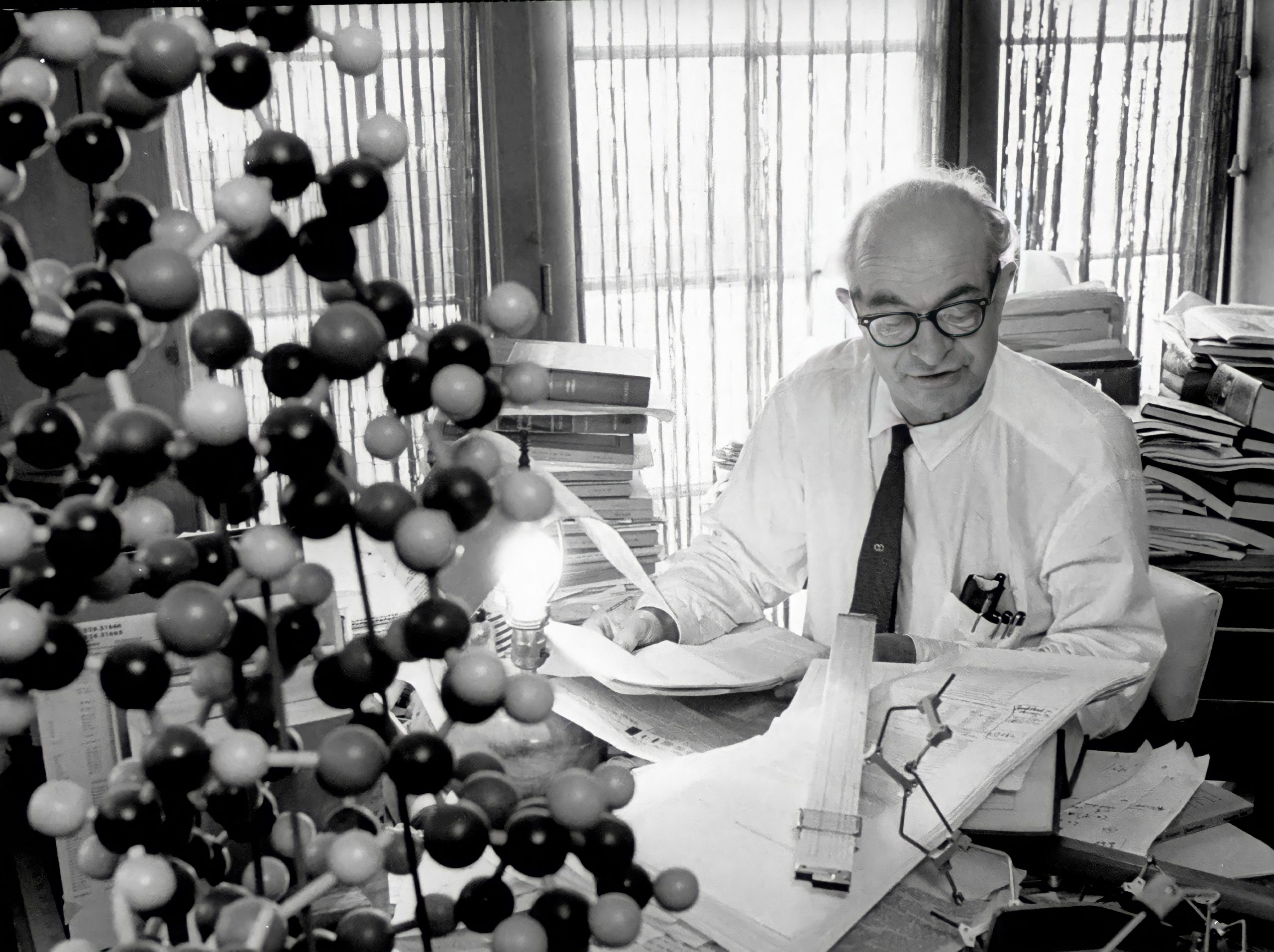

The young scientist first made his mark in the world of chemistry with his use of X-rays to examine the molecular structure of crystals. This work led him to a more thorough investigation of the nature of the chemical bond. Pauling revolutionized chemistry in the 1920s with his application of quantum physics to the study of chemistry. He used the new theory of wave mechanics to explain molecular structures which had baffled chemists for years. Pauling’s resonance theory proposed that some molecules “resonate” between different structures, rather than holding a single fixed structure. This insight made possible the creation of many of the drugs, dyes, plastics and synthetic fibers we take for granted today. Pauling publicized his findings in a series of papers culminating in an essential work of modern chemistry: The Nature of the Chemical Bond and the Structure of Molecules and Crystals.

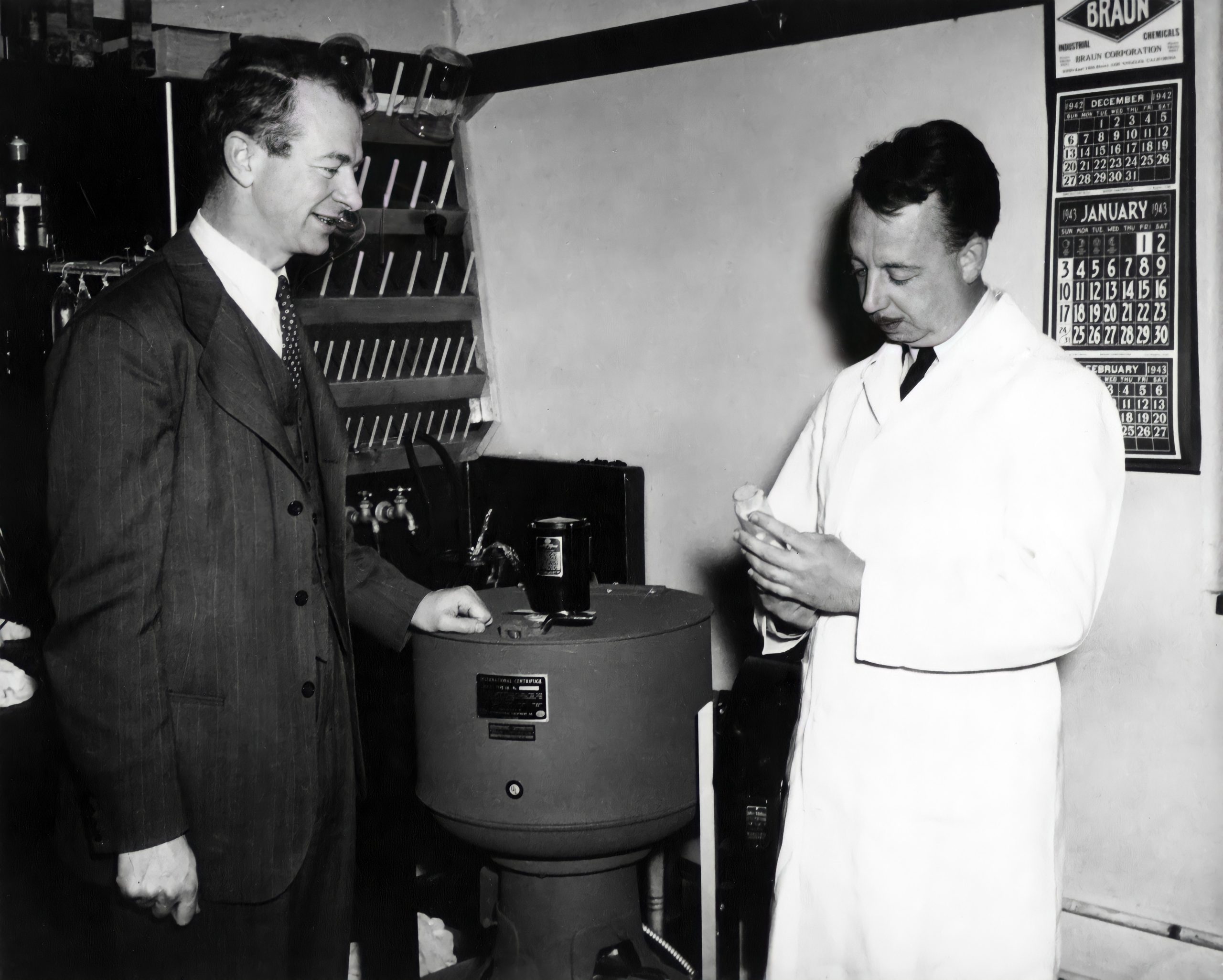

Dr. Pauling next turned his attention to the study of organic substances, particularly proteins. By 1942, Pauling and his colleagues had succeeded in producing synthetic antibodies, a major breakthrough. In 1945 Pauling was co-chairman of a project which developed a substitute for blood plasma. In 1949, he performed a groundbreaking study of sickle cell anemia, a disease that disproportionately affects men and women of African descent. In 1951, Pauling and Robert B. Corey described the atomic structure of proteins for the first time. This work had enormous implications for the struggle against disease.

The detonation of the first atomic weapons in 1945 posed an ethical dilemma for Pauling. The more he studied the effects of radiation, the more he became convinced that a nuclear war, or even the continued atmospheric testing of these weapons, could do irreparable damage to the environment and the human population. Because the government was attempting to conceal the dangers of nuclear testing from the public, Pauling believed it was his duty to speak out, but in the first years of the Cold War, many Americans considered such dissent treasonous. Pauling could not remain silent. In books, interviews and press conferences, he educated the public about the hazards of radiation and campaigned for peace, disarmament and the end of nuclear testing. These activities cost him friends, funding for his research, and the job he had held at Caltech for 33 years.

The State Department revoked Pauling’s passport, but when he won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1954 and was unable to leave the U.S. to accept it, the pressure of world opinion forced the Department to relent. Pauling continued his peace activism, and in 1957 drafted a petition calling for an end to the atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons. By the time Pauling delivered his petition to the UN, he had collected the signatures of 11,021 scientists from all over the world. This campaign led to a Nobel Peace Prize for Pauling in 1962, and to the first Nuclear Test Ban Treaty.

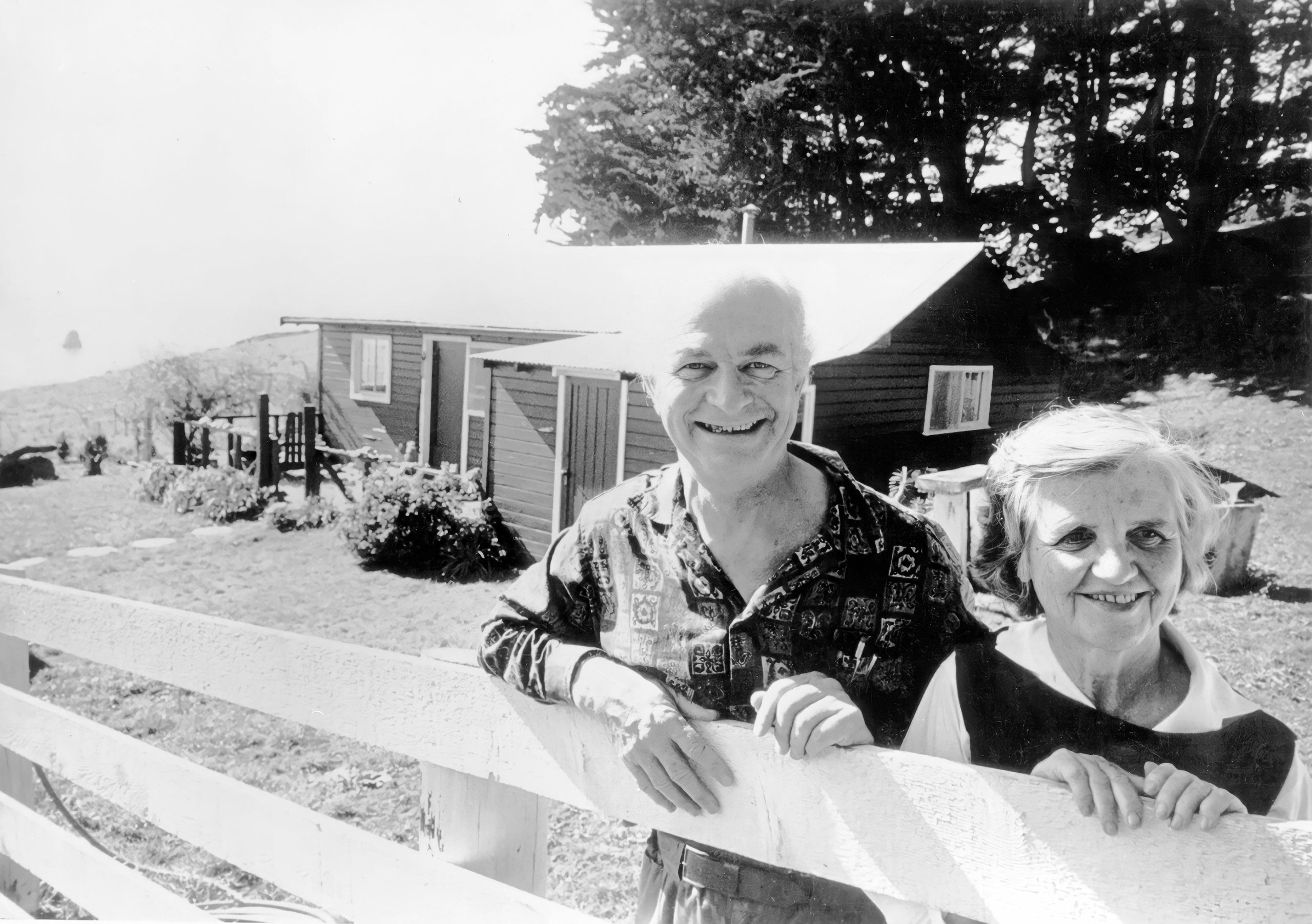

Linus Pauling remained active in anti-war movements, but he won even greater fame for his studies of the role of nutrition in fighting disease. His 1970 book, Vitamin C and the Common Cold, recommended megadoses of vitamin C to ward off colds and lessen their symptoms. Millions of people now follow this advice. Pauling’s theory of “orthomolecular” substances and his views concerning the potential role of vitamin C in fighting cancer have not won wide acceptance in the medical community, but many researchers have followed where he led in studying the role of vitamins and other nutrients in preserving health and fighting disease.

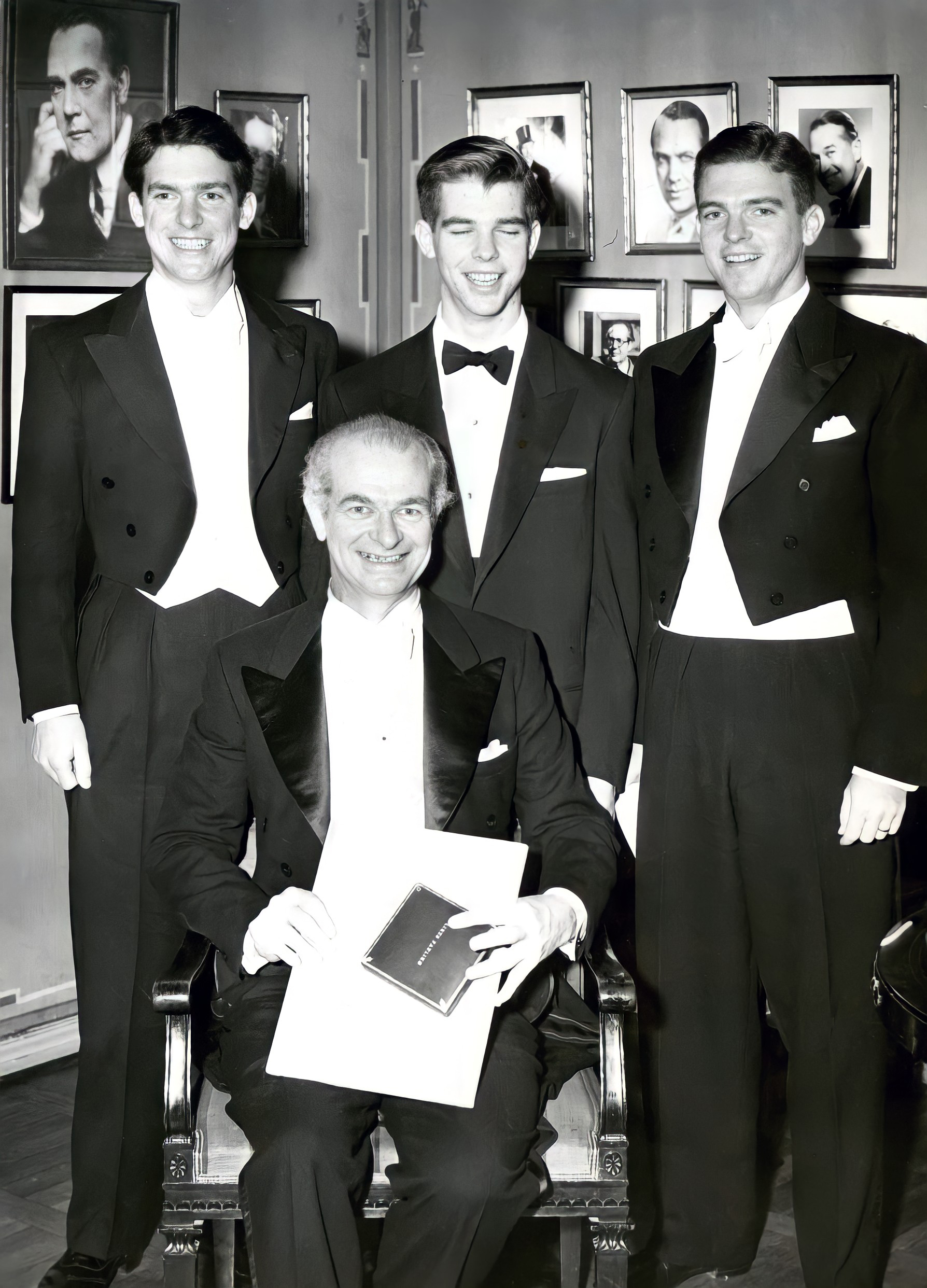

In 1973, Dr. Pauling founded the Linus Pauling Institute of Science and Medicine. From this base, he continued his research and worked to educate the public about the dangers of smoking and the benefits of vitamins. He received numerous honors, including the Presidential Medal for Merit and the National Medal of Science. He published books for the general reader on a variety of subjects, from one of his first, No More War, to one of his last, How to Live Longer and Feel Better.

Linus Pauling died on August 19, 1994, at the age of 93.

“A couple of days after my talk, there was a man in my office from the FBI saying, ‘Who told you how much plutonium there is in an atomic bomb?’ And I said, ‘Nobody told me, I figured it out.'”

In the late 1940s, few Americans had any idea what the long-term effects of nuclear radiation might be, and their government wasn’t telling them. Dr. Linus Pauling had already won renown for his application of modern physics to the problems of chemistry when he took on the unpopular task of informing the public about the dangers of nuclear weapons.

Pauling endured ostracism and ridicule for his uncompromising stand, but went on to win two Nobel Prizes: the 1954 award for Chemistry and the1962 Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to end the open-air testing of nuclear weapons. To the end of his 93 years, Linus Pauling devoted himself to the cause of world peace, to the struggle against disease, and to educating the public about a multitude of health issues, from the hazards of smoking to the benefits of vitamin C. Pauling’s work as a chemist would have been sufficient to earn him an honored place in the history of science, but his humanitarian efforts made him a beloved figure around the world.

Quite early in your career, you made historic discoveries concerning the nature of the chemical bond. Could you explain the background of this work for us?

Linus Pauling: After the electron was discovered in 1896, and the nucleus of the atom — an extremely small part of the center of the atom — was discovered in 1911, it became possible to determine many properties of molecules, such as how far apart the atoms are. That hadn’t been available for experimental study before. X-ray diffraction was one of the methods. I was fortunate in being able to use this essentially new experimental technique discovered in 1914, eight years before I became a graduate student, in attempting to answer many questions that I had formulated about chemical substances and their properties. And yet, they had only experimental answers to them.

The next important development was that…

The theory of quantum mechanics was discovered in 1925 and 1926. This was an improvement on the old quantum theory. The old quantum theory was an approximate theory which sometimes worked in a very remarkable way, and sometimes failed. But quantum mechanics — so far as chemistry is concerned — quantum mechanics is the basic theory, and there is nothing wrong with it. It works.

I realized in 1926 already that quantum mechanics could be applied to answer many additional questions about the nature of the chemical bonds, the structure of molecules and crystals. So, during the next ten years I was able to apply quantum mechanics to chemical problems in very productive ways, changing the whole basic nature of chemistry in such a way that essentially all chemists make use of these new ideas, along with the old structural chemistry that had been developed much earlier.

It must be very exciting to be involved with something that you realize, at least later, is a turning point, the opening of a door for scientists and researchers to walk through into a new area of discovery.

Linus Pauling: Yes. Someone asked me, not long ago, what was the discovery I made that excited me the most? And I answered that it was the basic discovery about directed chemical bonds that I made in January of 1931. I had published a paper in 1928, two years after I began learning quantum mechanics, in which I said that from quantum mechanics, by a treatment that I call “the resonance theory,” I could explain the tetrahedral nature of the bonds of the carbon atom, and that I would publish details later. Nearly three years went by before I published the details.

In 1928, I was working with the quantum mechanical calculations — which were very complicated mathematically — and I managed to derive the result that the carbon atom would form four bonds in tetrahedral directions, but it was so complicated that I thought, “People won’t believe it. It is so hard to see through this mass of symbols and equations and relationships that they won’t believe it. And perhaps I don’t believe it either!” It took a long time for me to simplify the quantum mechanical equations so that they were very easily applied to various problems. So around January 19, 1931, late in the day, I had this idea. I can use a simple method of simplifying a power method of simplifying these equations. Then I can apply these simplified equations to various chemical problems. So I worked nearly all night, very excited about applying this idea. I not only can easily derive the tetrahedral arrangement of the bonds of the carbon atoms, but also various other arrangement of atoms around a central atom, not only tetrahedral, but also octahedral ligation, and square planar ligation, which does occur with certain substances. And I did make predictions about relationships between magnetic properties and the arrangements of the atoms around each other. I considered that paper, which was published 17th of March, 1931, as my most important paper, and I believe I am right in saying that it is the one that developed the greatest feeling of excitement in me.

Could you tell us something about the obstacles you’ve encountered along the way?

Linus Pauling: So far as my scientific career goes, of course, there was the decision that I made in 1945 — ’46 perhaps, but starting in 1945 — and that may have been made by my wife rather than me, to sacrifice part of my scientific career to working for control of nuclear weapons and for the achievement of world peace. So for years I devoted half my time, perhaps, to giving hundreds of lectures and to writing my book No More War, but in the earlier years especially to studying international affairs and social, political and economic theory, to the extent that it enabled me ultimately to feel that I was speaking with the same authority as when I talked about science. This is what my wife said to me back around 1946. If I wanted to be effective, I’d have to reach the point where I could speak with authority about these matters and not just quote statements that politicians and other people of that sort had made.

What was it that first got you interested in becoming an activist in the social and political sense?

Linus Pauling: When the atomic bomb was dropped at Hiroshima, and then at Nagasaki, I was immediately asked, within a month or two, by the Rotary Club perhaps in Hollywood, to give a talk, an after-dinner talk about atomic bombs. My talk, as I recall, was entirely on what the atom is, what the atomic nucleus is, what nuclear fission is, how it’s possible for a substance to be exploded, liberating 20 million times more energy than the same amount of dynamite or TNT liberates. A couple of days after my talk, there was a man in my office from the FBI, saying, “Who told you how much plutonium there is in an atomic bomb?” And I said, “Nobody told me, I figured it out.” And he went away and that was the end of that. But, I kept giving these talks and I realized that more and more I was saying, “It seems to me that we have come to the time when war ought to be given up. It no longer makes sense to kill 20 million or 40 million people because of a dispute between two nations who are running things or decisions made by the people who really are running things. It no longer makes sense. Nobody wins. Nobody benefits from destructive war of this sort and there is all of this human suffering.” And, Einstein was saying the same thing, of course. So that’s when we decided — my wife and I — that first, I was pretty effective as a speaker. Second, I better start boning up, studying these other fields so that nobody could stand up and say, “Well, the authorities say such-and-such a thing…”

What goal did you have in mind when you started to speak out about nuclear weapons?

Linus Pauling: Well, back in 1945, my first talks were just pedagogical. I was just explaining nuclear fission. Then I began rather gradually expressing the opinion that the time had come to work for international treaties and international law to settle disputes rather than to use the barbaric method of war, made especially barbaric by the nuclear weapons. So, I was working toward the goal of a world without war. But, I didn’t ever think that I would attain the sort of prominence and so forth that I have obtained. The McCarthy period came along, of course — 1950, ’51, ’52 — and the others, many of the other people who had been scientists who had been working on these same lines, gave up. Probably saying, “Why should I sacrifice myself? I am a scientist. I am supposed to be working on scientific things, so I don’t need to put myself at risk by talking about these possibilities.” And, I have said, perhaps I’m just stubborn. I don’t like the idea. I have said, “I don’t like anybody to tell me what to do or to think, except Mrs. Pauling.”

I ran across that statement in some testimony I was giving before a Senate committee. I said, “Nobody tells me what to think, except Mrs. Pauling.”

You took the information that you saw, and the concerns that you had, and you organized scientists. Tell us about the petition that you circulated in 1958 and why you began that.

Linus Pauling: I had been talking about the need to control nuclear weapons, to prevent a nuclear war and to make treaties for world peace for a dozen years by 1957.

I was asked to speak at the honors convocation at Washington University in St. Louis. During the preceding months there had been additional information released about damage done by radioactivity from testing of nuclear weapons, and by the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs. So, my talk was about that. It got a tremendous response from the audience when I said, “We have to stop the testing of nuclear weapons in the atmosphere because hundreds of thousands of unborn children and people now living are being damaged.” So with two other professors, Barry Commoner and Ted Condon, I decided to write a petition. The next day we met, each of us had written a version of the petition, and I think mine was, essentially, the one selected by the three of us. We sent immediately, mimeographed it, and sent it out to 25 scientists that we knew. They all sent it right back, signed. So then I got back to Pasadena and my wife and I and some of our students and other people in the lab got busy and sent out hundreds of copies with the names of these first 25 signers — or perhaps there was 25, the three of us and 22 others. And, within a month or two I had 2,000 signatures from American scientists which I presented to Dag Hammarskjold. Scientists from all over the world began signing this petition. Originally, it was a petition by American scientists, but then it became a petition by world scientists. I think it was about 9,000 signatures that I gave, my wife and I gave to Dag Hammarskjold, and ultimately, about 13,000 scientists all over the world had signed this petition. So, that had a great effect, and I think even on President Kennedy, because a few years later he gave a speech about a need for a treaty limiting bomb testing and of course pretty soon this treaty was made.

Your views and actions came under a great deal of scrutiny during that period, and a great deal of suspicion. Would you talk about that period?

Linus Pauling: Well, it was a difficult period. For example, my scientific work was in considerable part supported by grants from the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health. I got a communication that these grants were not going to be made, despite the letter I received two months before that the grants were going to be made.

For a while I didn’t understand what it was about, and I telephoned the National Institutes of Health, and the man that I talked to said, “You have associates, why don’t you split up the application. You can apply for part of the work, and your associates, Dr. Corey and Dr. Campbell, can apply for other parts.” So we did that, and we sent in these revised applications. In another week Dr. Corey and Dr. Campbell had their grants approved, even the amount increased and the period extended, but they never acted on my application.

I was fortunate that this political action by the National Institutes of Health, who were worried about McCarthyism, didn’t seriously interfere with my researches. But there were, I understand, 40 scientists who had their grants canceled at this time. I remember talking with one of them at Columbia University. He was despondent. He didn’t know what to do. The university wouldn’t support him, and his work was more closely knit. He didn’t have an associate who could apply for the grant.

So there were scientists who were really very hard hit in their scientific work by this political action. Oveta Culp from Texas, who was Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, was frightened enough by McCarthy to have the people go over the list and select people they thought might be attacked by McCarthy, and cancel their grants. That was one thing that happened.

The State Department prevented me from traveling for two years. The first time, when the Royal Society of London was holding a two-day conference to discuss my work, I was to be the first speaker [to discuss] work on the structure of protons, an international conference just to discuss these discoveries that I had made. And, I couldn’t go to the conference because I couldn’t get the passport. So for two years, the State Department caused trouble for me. They wouldn’t tell me why. They said “Not in the best interest of the United States,” or “Your anti-Communist statements haven’t been strong enough.” I was having a scrap with the Communists — the Russians and the Soviet Union — at the time, and I was critical of the Soviet Union, but they used that as an excuse, saying they weren’t strong enough, my statements. I’m sure this interfered seriously with my work. When I was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, The New York Times had an article saying, “Will Professor Pauling be allowed to go to Stockholm to receive this Nobel Prize?” So I received the passport, which had been turned down only a short time before. It was sent to me.

Senator Hennings of Missouri was chairman of a committee in the Senate, investigating the State Department’s passport division. The Assistant Secretary of State was testifying after I testified. Senator Hennings said, “How did Pauling happen to get his passport then? Was there an appeal?” They said, “A sort of self-generating appeal.” So Senator Hennings said, “Do you mean to sit there and tell me that the State Department of the United States of America allows some committee of foreigners in a foreign country to decide which Americans will be allowed to travel?” Well, he didn’t have any answer to that question.

You had some difficulties in the academic world too. Caltech didn’t look kindly on some of your activities.

Linus Pauling: The trustees, of course, were mainly business men, and conservative, and supporters of the Cold War, and they seemed to consider that working for peace between the U.S. and the Soviet Union was in some way subversive, as compared with preparing for a war that would rid the world of the menace of communism. Probably socialism worried them rather than communism.

The trustees tried to get the Institute to fire me and a committee was set up — I didn’t know about it at the time, learned only later they reported that they couldn’t find a way by which I could be fired. I wasn’t guilty of moral turpitude in the usual sense, which was one way in which a professor can lose his job. So they began sort of harassing me. I was chairman of the Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering. The president said, well, that’s one job they could take away from me which would mean a decrease in salary. I didn’t mind. I had served in that position for 22 years and felt that I had done my duty with respect to that administrative job. But, they began interfering with my research projects and I decided that I was going to have to leave the Institute.

When I received word that I had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, I found, when I returned to Pasadena, that the president had stated to the Los Angeles Times that it was pretty remarkable for any person to receive two Nobel Prizes, but there was much difference of opinion about the value of the works that Professor Pauling had done. So I decided that the time had come for me to resign, and I did. I didn’t like that. I had been at the California Institute of Technology for 41 years then, and I thought it was really the best institution in the world. My opinion of it is still a very high one. With respect to science, it comes close to being the best university in the world. So I wasn’t happy about leaving the Institute, but I did leave.

Did anyone at Caltech express any regrets about this?

Linus Pauling: The Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering did not hold a party to celebrate my getting the Nobel Peace Prize. Whereas, they had held one when I got the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. But, the Biology Division did hold a party for me. The biological scientists, I think, were more sympathetic to what I was saying about damage done by fallout radioactivity and carbon-14 than the physical scientists. I was, I think to some extent, disappointed that my colleagues in the Institute did not express sympathy with me in this situation.

Did you have any discussions with any of them on a one-on-one basis about that?

Linus Pauling: I’m not sure that I can remember. Beadle, the chairman of the Biology Division, had been a member of the committee to recommend to the trustees whether they could fire me or not, and he told me about it some years later. I don’t remember when it was that he told me about it. I note that he was, in a sense, sympathetic to me. There were many people at the Institute that I considered my friends, and perhaps if they are still alive, still consider them my friends. But it was a difficult period, so I can’t complain about their not being open in expressing sympathy for me.

Do you think the scientist in particular has an obligation to be engaged in those kinds of activities?

Linus Pauling: Well, yes. I have said this for many years. Almost every problem in the modern world has some scientific content, sometimes very great scientific content. For example, the argument going on now about the destruction of the ozone layer, or the nuclear winters if there were to be a nuclear war. That seems no longer to be an important matter. I think the chance of having a nuclear war is much less than it was before. Or the greenhouse effect with an increase in temperature of the earth.

But all minor problems too, the ecological problems, they are largely scientific problems. And while scientists may not be able to decide what the best course is to follow, nevertheless, I think their judgment has to be a little better about these problems than that of the non-scientist. I have said that the scientist has an obligation to his fellow citizens to help them to understand the problems and to make the right decisions.

You were a pioneer in the field of molecular biology, but you encountered resistance and criticism again when you began to write about vitamins and disease.

I wrote my book Vitamin C and the Common Cold in 1970, August 1970, sitting mainly there in this room. I thought, you know, everybody will be happy to have this book that tells about how to keep from suffering with the common cold. The doctors will be happy, they won’t be pestered by patients with this minor problem the way they are now. They can concentrate on more serious diseases. And, what happened? A month later, The Medical Letter published an attack on me for having written this book. And, all the other medical… Modern Medicine published an attack on me for a whole lot of things. I wrote to the men, the editor of Modern Medicine, and said, “You remember that Modern Medicine gave me the Modern Medicine Award four or five years ago for my work on sickle cell anemia. And, here you are attacking me.” And, then I went up and said, “I want you to publish this retraction.” And, I wrote a very abject retraction on all the points, and they published it just the way I had written it, retracting. I’ve been astonished at the response of the medical profession to orthomolecular ideas.