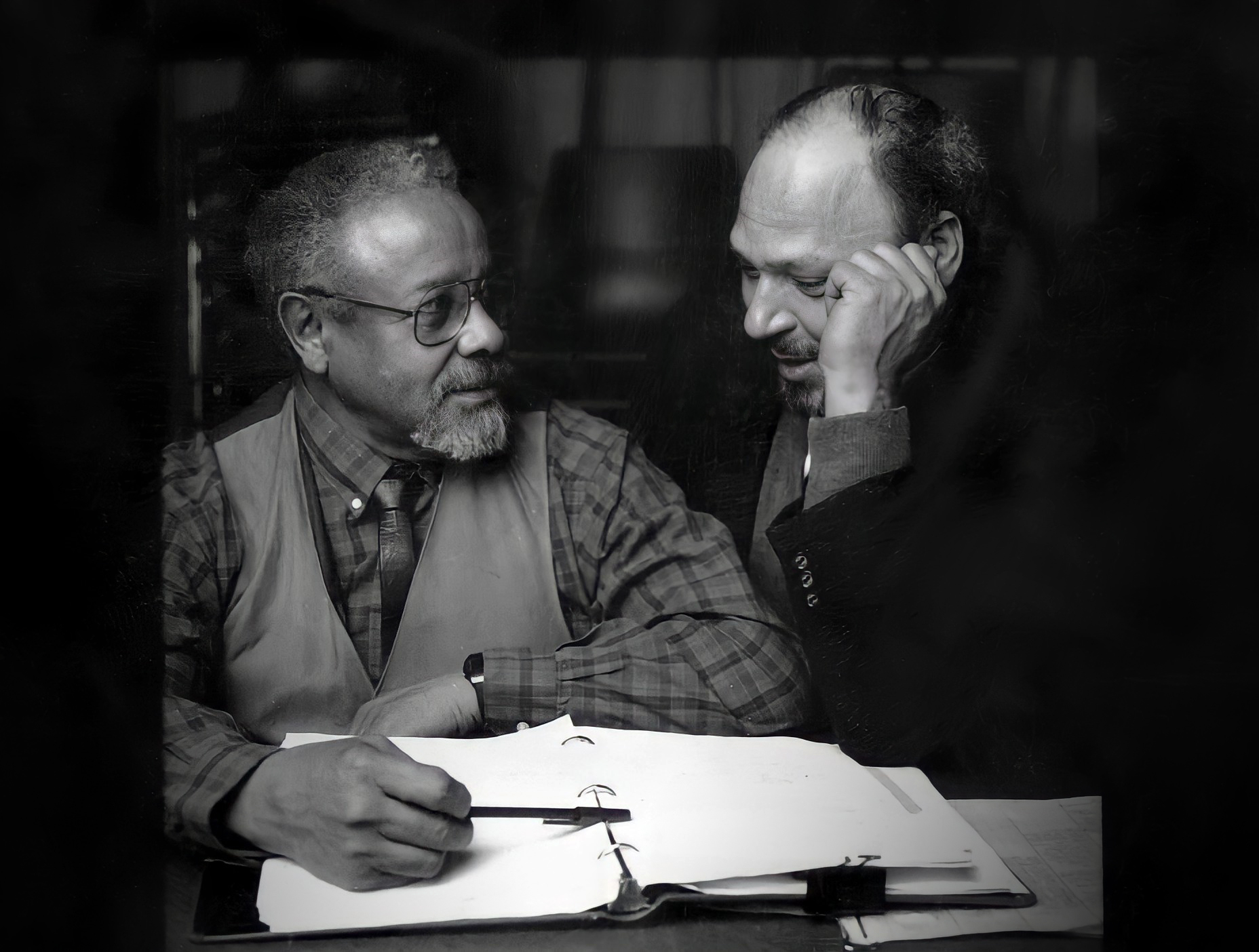

What were you looking for when you found August Wilson? What was it in August Wilson?

Lloyd Richards: Genius. We were looking for genius. I run a program called the National Playwrights Conference. I’ve run that since 1968. Every year I invite playwrights to submit their work to us. We accept that work, and every year around 1400 scripts. I have readers who read the plays, I read all the reports, and selectors, and I’m a part of that. What are we looking for? I remember talking to a wonderful man who ran the BBC and we were comparing notes. I asked, “What’s your ratio?” He said, “Well, ten percent of everything that I get is worth reading. That’s 100 in 1,000; 10 percent of that is worth doing. That’s ten in 1000. And 10 percent of that is exceptional, which is one in 1000. And the other guy may get it.” So that’s what you are looking for. You are looking for that exceptional, unique voice for the theater. It’s really like looking for a needle in a haystack. Looking for genius. It may be in its rough form, and you may be wrong, but that’s what you are looking for.

I know that it’s not easy to find, and it’s not easy to develop even once you find it. It’s hard to try and develop a playwright. You know what it costs? It isn’t a matter of sitting somebody down and having them write something and rewrite it and rewrite it. In order to really understand their work, they have to see it done. What does it cost to get work done? An aspiring playwright, where do they get that from? So our program called the National Playwrights Conference, we invite people to submit. Then we try and select from those that we will work with, in one month of the year.

And August Wilson submitted something?

Lloyd Richards: Yes. We take those playwrights who we select, and for one month, we bring them together with very talented directors, talented actors, and we work on their scripts with them. We do a stage screening, and we discuss the work with them. We try and affect their work in that manner.

Now August Wilson, he will tell you, he submitted to us — he is a poet who was in the process of teaching himself to become a playwright at the suggestion of some friends. He was rejected by us five times. It was on the fifth try that he was selected. He even tells the story that once he didn’t believe that we had really read his play, so he submitted the same play the next year, and it was also rejected. He thought, maybe these people have a point. But, that is the important part of that is the fact that August Wilson did not arrive full blown. He was a person who did not, in getting rejected, turn around and say, “Aw, there is something wrong with you,” the rejector. He ultimately accepted the fact that he was in process, and there may have been something wrong with what he was doing, and he had to learn more and he had to do more. He did, and he finally got to that point where his work was accepted for work. Finally, that was when he came to the Playwrights Conference and our relationship began.

What about directing Fences? What does Fences bring to mind for you? What kind of a challenge did that play present to you?

Lloyd Richards: August brought us Fences after Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom. Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom was really two short plays that he was trying to put together. One was in the band room, and one was with Ma Rainey. Our work together was really the cementing of those two plays together, making them integral to one another. And so then he wrote Fences. We did it at the O’Neill Center. When we did it at the O’Neill, it was four hours, and 15 or 20 minutes. I say 20, he says 15. Our work on that began to be…to find what the true line of that material was. Because it was material, a lot of wonderful material, and hidden in it was a story or a tale. Our job became one of searching for that line, and putting that line through the material, and lifting it up and see what hung on it, what belonged there, what was essential, what was necessary, finding the core of the life of that man. And we struggled to find that. I think the key moment when we found that it was in a scene that he had in a speech after the death of the woman who he had become involved with, and who had borne his child. When he heard of her death, he used to have a speech to God. And I finally said to August, “That’s wrong. He doesn’t talk to God. This is a man who lives with death. He talked about it in the first scene, that death is his constant companion. Death is the thing that he is doing battle with for his life.” That speech was changed into a conversation with death. Not just a conversation, but taking death to task; death had betrayed him and stepped into his family. There was the essential inner conflict in that play, the thing that held everything else together, the thing that man was dealing with throughout the play. That became one of the core decisions in the play, that began to bring it all together for us. It was hard work. But it was always good work. Good, not in the sense that we did good work, but good in the sense that it was challenging, and it responded, and we responded to it.

What inspires a young man in Detroit, a young black man, in the 1930s and ’40s, to pursue this life? Why the theater?

Lloyd Richards: I guess the theater because I couldn’t do anything else. By that, I don’t mean I couldn’t do anything else, I mean I couldn’t do anything else. What inspires or what started it, that’s a question I get very often, and I’m not sure exactly when it began. I do remember certain things. I remember being in school.

I remember studying Shakespeare as a young person in school, and I remember an assignment to memorize a soliloquy, which I did. I was asked to stand up in front of the class and do it. I did it and I found myself saying beautiful words, phrases, thoughts that I agreed with, and I found myself expressing myself through someone else’s words. There were people there and they responded; a connection was made. And I guess there was a connection made in me, that I felt something, or received something in that. That was deeply satisfying. That didn’t mean I left the front of that class and went into the theater.

In Detroit where I grew up — I was born in Toronto Canada — there was not a theater that I went to. I did not look at that as a way to make a living, or a way to make a life, which is really what it amounts to. I looked at it as an experience. I had a few more of those as time went on. The theater was not a place a young black man aspired to, because you were no images there, you were not reflected there. You were not reflected in pictures around you, or on the stage around you, except occasionally [by actors like] Canada Lee and Paul Robeson.

I found myself in college. I was a pre-law student. Why pre-law? Because that was a way not only to make a living, but to secure one’s life. There were certain things that were open where you did that. If you were going to college, you really went for those things. You became a doctor, you became a lawyer; forsaking all that, you became a teacher or a social worker or a minister. That was it. And of the five, I thought law was something I aspired to. So I went to college in pre-law. But I found myself taking what was called in that day speech courses and interpretive reading courses. Gradually, doing things in the theatre, but I was still pre-law until I found I had more speech courses than pre-law courses.

After three years of it, when I should have gone to law school, I ended up not going to law school and determining that I would have a life in the theater. I had to decide at that point what security was, what it meant. Was security property? Was security money in the bank? Or was security getting up in the morning and not counting the hours? Having a life, not a job. The theater was something that seemed to satisfy my life-need. I was not concerned about, would I make it, would I not make it, would I be successful, would I not be successful. The opportunity to function in that area was something that compelled me and I ended up in the theater.

Was there a moment, an event or episode where the light went on in your head, and you said, “This is what I have to do.”?

Lloyd Richards: No. I found myself doing it. I was already doing it, and all I had to do was accept what I was doing. I guess the moment was when it was time to go to law school, and I didn’t go to law school. Then events happened after that. But I had made the decision, and I accepted the fact that I had made that decision. That was what it was going to be.

Everybody told me I had made the wrong decision. That was not the way to make a life. What would happen to me? I just had to take that, accept it, and go on. I had made my decision.

What was the first play you saw that had an impact on you?

Lloyd Richards: Certainly in college I saw the theater. Things that were memorable to me: Paul Robeson in Othello, Canada Lee in The Duchess of Malfi, and as Bigger Thomas in Native Son, and other plays. Those were people who began to inspire me in a very personal way, because they were black and there were very few of them, and they, in their exception, said, “Okay, something is possible.” I determined that, yes, it was going to be a hard job. I may be rejected. There may be many times that I might be rejected, and that was true. But I wouldn’t be rejected because I wasn’t prepared. So, I set about preparing myself.

My time in school at Wayne University, which was a grand place to be for that, was used to contribute toward my future, my life. There were the questions of would I teach. When I talked to my advisors at Wayne University because I attended Wayne University, they suggested that they might help me find a place in a black college somewhere to teach. Thanks a lot, but that isn’t what I intended. But Wayne had a wonderful program. It had a speakers bureau where any organization could call the university and get a speaker on any side of any subject; I was a part of that. They had a reader’s bureau where any organization could call and get readings of poetry, and other things on any subject or for any occasion; and I was part of that. You went out on those things, and you [were paid] five dollars, which was very important at that time.

I began to work with the radio guild at Wayne. They had a wonderful radio guild, they were very talented people there, most of whom worked in radio in Detroit and nationally. Many people came out of Detroit at that time, and they were our faculty. I was taught by them, got an opportunity to work on radio because we did original radio out of the university. I did everything. I acted, I directed, I did sound, I did all of the things that one does in radio. I was trained in that, and ultimately in theater, but there were very few roles in the university for a young aspiring black actor to play. So there were problems about that, little to do, but one way or another, we found ways to do them.

What was life like, growing up in Detroit during the Depression?

Lloyd Richards: My father was a master carpenter. I was born in Canada, of parents with a Jamaican background. Ultimately we came to Detroit because Henry Ford advertised work for five dollars a day, which in the ’20s was a good deal of money. So our father went ahead, and my mother and the flock followed. I grew up on the east side of Detroit, attending school, and finally we moved to the west side, bought a house which we ultimately moved out of, and moved to North Detroit where we bought another house.

Father died when I was nine years old, and there was a flock of five and my mother kept us all together. Although how, during the Depression, who knew? There were things like aid to dependent children. There were things like welfare, which we were a part of. But she was determined that those of us who wished to would attend college. I ultimately managed to do that—worked my way through college. Growing up in Detroit was both fun, and tough. Tough in the sense of where is the next meal coming from, where is the next paycheck coming from? My mother took in laundry; I remember the kitchen, filled with large white shirts that she was doing for some businessman living out somewhere. My mother did that, and many other things, so that we could not only survive, but find that way to make a life. A wonderful woman, a very strong human being. I had great, great affection for her. She did the impossible. There were suggestions when my father died that the family be broken up, that this uncle take one, or somebody else take another, but she would have none of that. The family had to stay together, and we did.

And how were you affected by that? Did you have to go to work?

Lloyd Richards: Oh, yes, I worked.

What did you do?

Lloyd Richards: I worked in a barbershop one time. I sold papers from the time I was eight years old or something like that, which was tough because people didn’t pay you. There you were running down the street delivering papers, and you’d go around on Saturdays to collect the few pence that it was. That was tough because people took advantage of kids. I sold magazines, Ladies Home Journal, and all those other things that one does to make a buck. Then I worked in a barbershop, I shined shoes, cleaned up the barbershop. At college, I ran the elevator. You do all kinds of things. That makes it possible not only to live, because it wasn’t just subsistence that we were concerned with. We were concerned with the future, and making a future possible, by going to school, getting an education, and making a life.

What kept you in school? It seems to me it would have been easy enough for you to say, “Look, I’ve got to work, I’ve got to help to support the family.” What kept you going?

Lloyd Richards: Well, the expectation of the family. The support of the family. My older brother, he went to work, he dropped out of school to work after high school. My younger brother got involved in a training program at Henry Ford’s where he studied engineering, and received payment for it. We expected things of one another. Not only the immediate family, but my uncles and aunts. The family expected that you would do something to better yourself, to better your life. That expectation and support was very important to me. A lot of pride in my family. I remember my old aunt, the head of the family, she would say, “You are a Coote.” That was my mother’s maiden name. “And a Coote does…” And she’d go on. You listened to Aunt May, and you did what she said. All the rest of the family were all very supportive of one another; they were trying to do the same things.

What kind of a student were you?

Lloyd Richards: Well, I might be considered a pretty good student. I worked hard.

Were there any teachers or books that influenced you when you were a kid in school?

Lloyd Richards: I can’t recall that far back the books that influenced me. I remember a redheaded teacher, when I was in the early grades, maybe first, second, third grade. Mrs. McGinnis, I recall that she was particularly supportive. And other people like that.

Could a kid under those circumstances have pastimes? What did you do for fun? What about sports?

Lloyd Richards: Well, we would play baseball in the street, ride bicycles. I loved swimming, and we’d do that. But of course, you weren’t encouraged in high school, because there were no black kids on the swimming team. The swimming teams practiced in the summer at some country club or were taken places where it was not at that time acceptable to bring a young black person. I did win decathlon medals and things like that—which we did in grade school—for running, jumping and what not, but I was not an athlete.

You left Detroit and came to New York. What were you looking for?

Lloyd Richards: I came to New York after the Second World War. I was in the Army during the Second World War. First I came back to Detroit because I hadn’t finished my masters. I re-enrolled in school, but I had to get a job. I looked around for what jobs would be available, and I saw there was a need for social workers. I wasn’t really interested in a job; I applied for that job because I knew I was not qualified. They accepted me. They said, “Can you start tomorrow?” I said, “No, I couldn’t possibly start tomorrow.” And they said, “Well, when can you start?” I said, “Well, maybe in two weeks,” thinking that they would reject me if I said that. They said, “Fine.” So I became a social worker, and went to the office every morning. At that time, in school…

In school, I had become involved with other people who were interested in making the theater their life, and we began a theater in Detroit. We got together one summer and formed a company called These Twenty People. There were twenty of us, that’s obvious, isn’t it? We got the city of Detroit let us use a large home in River Rouge Park that had a large living room. We decided to perform in that living room with chairs around it. We could seat, I forget how many people, not a lot. And we put a couple shows into repertory there, we did Hedda Gabler, and I forget what the second show was. But after the summer, we thought we ought to stay together and we formed a group called, the Actors Company. There was Harry Goldstein, who had been a few years ahead of me in college and graduated, and he headed up the company. Then there was a young man who had graduated in law a few years before, and he gave us, I think, a thousand dollars to start a theater. We went to the Michigan Showmen’s Association, who had a large room, an auditorium with no stage. They rented that to us and we built a stage. We put five shows into repertory that year. At the same time, I was doing my job as a social worker. I had gotten a job as a disk jockey on a radio station. I had a program from, I think it was 11:00 to 12:30 at night. What I did at that time, I went to work at 8:00 in the morning, arrived at the office, did my work at the office, went out into the field and did my visitations, then late in the afternoon I’d go to the theater where we rehearsed. I began directing, too at that time as well as acting. We would stay there and perform that evening, [then] I would leave there, go to the radio station, do my disk jockey job, and then either come back to the theater and help build or what not, or come back to the theatre and rehearse. Then I would bring a group of kids over to my place, which my mother loved, and raid the refrigerator. And that was my life for a while… a lot of wonderful people who we were involved with. So I began doing theater that way, in Detroit.

We were all aspiring to New York. New York was the place to go. There was no regional theaters such as exist now, where you had choices. It was: go to New York and start making the rounds. Start receiving the rejections, all for yourself, and accept the rejections. And everybody was leaving one by one. I determined that I would go to New York and I told everybody I was going. Nobody believed me; things were going too well. I knew I had to make that break then, or I would begin to feel very comfortable in Detroit. So I got a room at the “Y,” bought myself a footlocker and a suitcase. Nobody still believed it. And I packed up, and I went to New York. Now, everybody thought I’d be back in two weeks. Well, that was forty-some years ago, and I have been back to visit, but never moved back. I got a room at the YMCA, in New York. I knew it was going to be tough. I had been in the Army so I had 20 dollars for 52 weeks. The 52-20 club, if you remember, where all veterans got 20 dollars a week for 52. I thought that would be my base, that would give me a start, that would sustain me. I didn’t pay a lot of rent at the Y, and I could live frugally, which I did. There were a number of people from Detroit who had gone to New York, to try and make it, so there was a kind of Detroit club. There were three of my friends who had gotten an apartment, so we would all gather there, most days of the week for dinner and chip in and make dinner together, and make the rounds together, support one another, emotionally, artistically, however we could.

And you pounded the pavement.

Lloyd Richards: Oh, yes. You pounded the pavement. You went around to offices, you tried to get past secretaries, you offered your picture, you offered yourself. You went to the third floor at NBC — that was a hangout then for out-of-work actors. The third floor of NBC was the place where you could sit around, and the directors passed through. You tried to buttonhole somebody. Working actors also passed through, and you envied them. But it was the place that I learned what New York was about. I was the one looking over your shoulder. By that I mean, you’d be engaged in a conversation with someone on the third floor, and you’d always find that people I was talking to were looking past me, over my shoulder in some respect. They were trying to spot the directors who were passing through, who they might approach about a job. But yes, you pounded the pavement. That was the way you did it.

And what was the first job you got in the theater?

Lloyd Richards: Well, I got some work Off-Broadway, in Equity Library Theater.

And do you remember that first role, that first chance?

Lloyd Richards: No, I don’t remember the first chance. I remember the first Broadway role. There were various things that I did Off-Broadway. I was in a project, played Peewee in Plant in the Sun, at Equity Library Theater, played Stevedore with some wonderful people at Equity Library Theatre. I know I have a picture and I look at sometimes, and in that picture there was Ossie Davis, George Roy Hill, Jack Warden, Jack Klugman, myself, and others who have gone on to do other things. That was the place where people with some drive, some desire and, I guess, some talent, would function. Agents would come to see it; you were trying to get agents to see you. You were trying to get somebody to see you and change your life. So you did all kinds of things Off-Broadway for very little money. I was involved in a theater called the Greenwich News that I helped to organize. I acted there, and I guess I was for a while a managing director there, because I handled the money and tried to make the little that we made work. The production was in the basement of a church. You worked for anything. I also got some shots in radio. That was a hard place to work in because, as a black actor, there were very few roles.

I was going to ask about that—the obstacles you had to overcome as a black actor.

Lloyd Richards: You tried to get auditions and when you finally got an audition, they said, “Fine, good, hey, I love your talent, but we don’t have anything for you.” The fact was with there being so few roles, and the fact was, I did not necessarily in radio come over as a black actor. But they would say, “There are things you can play, but I can’t cast you.” Why? “Well, you know there are such things as sponsors, and our programs go into the South, and if it was ever known that you as a black actor were playing something else, then…” So, you ran into that all the time. You weren’t generally told that, but you knew that was behind it.

You knew it because there would be exceptions, the people who said, “I want you to do this, you are a talented young person, and you should work.” So, you’d end up with a shot on a show like Helen Trent, or Jungle Jim, or The Greatest Story Ever Told by Henry Denker — wonderful writer, human being. He used to cast me on that for a while. Then I had a running part on a show called Mr. Jolly’s Hotel for Pets. I was one of the major characters. I did play a role that was considered to be a black role, which was the assistant to Mr. Jolly. But I was on that for a while.

You have chosen a field, chosen a career that abounds with critics and criticism. How do you handle criticism?

Lloyd Richards: I don’t work for the critics. The critics are something that happens to the work. If I try to guess what the critics might like… I know my producers do that all the time. I’ve been a producer, and I am a producer, but I do the things I like. I do the things that really affect me. I do the things that mean something to me, where something of me is being articulated through the work. I say what I have to say. Now that may be accepted, it may not be accepted. I say it the best I can, and if they don’t accept it, okay.

They may control, to a certain extent, my livelihood, but they don’t control my life, and they don’t control my art. They are there, and sometimes unfortunately so. I think that we are in a position now where we don’t have enough critics to balance things out. There used to be a time when there were 15 newspapers in New York. So there were a lot of points of view at work that might be expressed. Now there are very few. So much hangs on so little, and that’s unfortunate. When I think of the investment of time, of energy, of life, that is involved in the creation of a theater piece, it’s sometimes sad what happens to it. That’s why we drive some of our potential artists into an area like television. It’s done before reviews come out. Okay, go on to the next one. That’s what is expected to be. But in the theater, you spend one, two, three years of your life invested in the work, and then you take it and you put it up somewhere, and wham! It’s gone. It’s not easy. I can understand people who work trying to anticipate that. But I don’t find it helps the work any at all.

How do you handle the pressures, the responsibilities, investing all of this into something that could be finished in a day or two days? You must feel responsibility to the work itself. You feel responsibility to the investors. You feel responsibility because it’s your life. There has got to be a lot of pressure.

Lloyd Richards: There is a lot of pressure. But that’s not what it’s about. The pressure comes for other reasons. The pressure comes from other people who have a financial investment. They bet on you. There used to be tip sheets that used to say, this is so-and-so directing, he’s a three-hit, two-flop man. You were rated like a horse. Fine, good, great. That’s their way of doing things. That’s betting on horses. They’re betting on your past. What’s sad to me, there used to be very wonderful producers who understood the process. But now you can be involved in a project with people who have the money it in, who don’t understand the working process. What they understand is hire and fire. That is what they understand. Why? “Because I don’t see it there today, it is not there.” No, it’s not there today, but it’s coming. Do you see where it started? Do you see the goal? Do you see where it is in relation to that? Do you see the investment in it that can bring it to that? Not a lot of people can do that, not everybody can appreciate that. So strange things happen. And lack of trust, which means a lack of knowledge of both process and talent.

I am going to remember that. That hits home in many ways. You’ve probably answered this, but in so many words, what does it take to achieve something in the theater, in drama, in your field?

Lloyd Richards: Well, beyond talent—that is the indefinable thing that is involved—it takes commitment. One person once said to me, “The theater is a place of survivors, people who have survived all those things you are talking about.” And what makes them survive, I assume, is a real deep belief in themselves… a need to express that, and then having the tools to do it with. I guess I may have some tools. I know in other areas of the arts, I don’t have the tools. I can have a wonderful image, but you put an easel and a brush in my hand, and a palette, and all those colors there, I cannot make that vision, as wonderful as it is, realize itself up on the canvas. I can’t do that. I don’t have the technique, and I may not have the talent for it, but I certainly don’t have the technique. In the theater, I have some technique. And I’m presumptive enough to think that after this length of time, maybe I had a little talent somewhere along the way.

What are your hopes for a graduate of the Yale School of Drama? What do you hope for these people who come through here?

Lloyd Richards: That they’ll make a contribution to the theater. That’s what I hope. We try and prepare them to do that. What I try to do at the Yale School of Drama, or have tried to do, is to create an environment where I can take the pressures off, and put the pressures on. Take the pressures off, in terms of success and failure, and put the pressures on in terms of acquiring knowledge, acquiring skills, acquiring craft, and utilizing that, and taking chances with that. To create that environment and support is my goal. So what do you do? You get the best people you can, in terms of the faculty, in terms of the administrators and staff, and you provide opportunities. You go out and you raise money, you beg and you borrow, and you do whatever you have to do to help to create that environment. Then you get the most talented students, and I think we’ve been able to do that to a great degree. Every year, since I’ve been here, we audition the applicants for the acting program. Over 1,000 applicants a year. We take 15 in the acting program. There are certain questions that we ask ourselves, past talent, having to do with commitment. Having to do with, “Will this person make a contribution to the art, to the theater?” We select in those terms, and we put together a company. We do the same with every other program in it, trying to create here an environment that is stimulating, where the students are stimulating to one another, challenging one another, and have a faculty that is supporting and challenging. That’s what we try to create.

Given the kind of expenditure of energy and imagination that exists in a program like this where students begin at eight o’clock in the morning, they go to classes until two o’clock in the afternoon, then everybody goes into rehearsal of some kind at two o’clock in the afternoon, and they work until midnight, and they perform, they support one another, they support the work, and they are studying continually, but what is sad is that the theater is not able to provide the kind of opportunity to utilize that energy, and that imagination to its fullest. We prepare them for that kind of a theater and that kind of experience, so they will take that with them wherever they go. They will be working in terms of that, whatever situation you put them in.

That leads me to a question that I know is dear to you, about the place of the arts in America. In light of the NEA controversy, and the debate about the role of government, what place do you see for the arts in this country?

Lloyd Richards: The arts are a reflection of our society, of its concerns, of its aspirations, of its possibilities. In every respect, it is also a challenge to our society. Those are its roles, and sometimes those roles become crusty. It was Ed Steinmetz who said a good writer is as a second government in his own country, which is why the government generally supports mediocrity rather than real talent. What is he saying? He is saying that the role of the arts is to challenge, is to question. It is not simply to pat on the back and support and wave. There are many, many responsibilities that it has, one of which is to question our society as it exists, and lead it to the possibility of making other choices. Sometimes, it isn’t to say that every artist is correct in his projection, but at least the challenge is there. Answer it again. There are times when you step on a toe, and if that toe is as influential as a few toes were, then you may have a bumpy time. But that does not change the role of the arts. And any true artist will not be changed by it.

It may change, which it has, the economic support of the arts in this country, and that’s unfortunate. But what it really affects is the fringe areas in a way where you get less money to support the seedlings, some of which are going to not work. And that’s unfortunate. There has got to be a willingness to accept failure, or to fail. We do it in science. We do it all the time. I’ve seen this marvelous movie, the old development of our space program, where you see the rockets. They are there: they fume, they flop over. We understand that in relation to science; they waste a lot of money. We expend very little on the arts in this country, shamefully little, unfortunately so. There is so much more that could be done, that should be done. But, we will survive it.

I was going to ask you another big question, which is race as a theme in your work. How does one best deal with the race issue in America in the arts?

Lloyd Richards: Deal with the race issue? I’d have to clarify that as a question for myself. If you are dealing with the race issue as it exists in this country, you can write about it. There are times when I know in my own history in the theater, when much of the work that it did, when it was of that nature, was something which was confrontational, antagonistic, and the core of the plot was racial attitudes. But that in many respects, past, in the sense that there is no longer an issue of whether I should belong, or whether I shouldn’t belong. There is a general acceptance, he ought to belong. The question is that I must in some respect mute the racism that does exist. It used to be very obtuse, very obvious; it is much less now. What you find now is, we have many minorities in this country, all of whom are contributing to the life of the nation, and all of whom have wonderful cultural aspects of their existence, which are revealed through their own artistry. We very often don’t see that, or understand it. We tend to look at everything tends to be looked at in terms of Western culture, when there are a lot of other cultures involved that have standards, very high standards. I know that one of the nicest things that happened to me, and I’ve had so many, but recently I was in Boston at the Huntington Theater, doing Two Trains Running, August Wilson’s play. We’ve done three plays there. This was the third play at the Huntington and I was at the back of the theater with my assistant, taking notes. When the show ended, I was still giving some notes. As people were going out, a couple stopped in front of me. A white gentleman said, “I want to thank you.” I said, “You’re welcome.” He said, “No, I want to thank you and August Wilson because you have permitted me something that I could not have gotten in any other way and elsewhere. You have permitted me into the lives of black people in this country.” Not into the problem between, but into the lives. Which is what much of August’s work does. Yes, there are all kinds of comments made in the work that stem from a human involvement as black people in the life of this country. But that’s not the core of the play, that’s a very major aspect of what makes people behave the way they do. Just the permission [to enter] into the life, into the music, into the rhythms, into the thoughts, into the attitudes. That opportunity to see that in an ongoing way permitted him something that he had not experienced otherwise.

Now that is true for every culture that exists in this country. We too rarely get the opportunities to go from our own position, the comfort or discomfort of our own culture into something else, and see the life as we are experiencing it from another point of view. These are characters, these are people who you drive down the street. I worked with Richard Wesley. I did one of his plays; he is a wonderful black writer. Most of his characters came from New Jersey, and we’re in New Jersey. He said, “I’m writing characters and putting them on the stage, that people who were driving through town, when they got to a red light in the district, would roll up their windows and make sure their doors are locked. And I just want them to get out of the car, and really see what’s happening on the corner.” I thought, yes, sure. That’s it. And that’s what must happen. More and more. We have to accept the fact that this society is not just created out of western culture standards, as part of the cultural baggage that came over from Western Europe. And it, too, has value, and that value has to be recognized.Growing up in the theater, I did not grow up in a black theater, because there was no black theater. There were very few writers, and their work was very rarely done. Nor did they get that opportunity to develop. I grew up with Shakespeare, Shaw—Chekhov is one of my favorites—and Ibsen. And I do their work, but I do their work, I believe, with some sensitivity and some knowledge because I grew up with those western cultural standards. I was exposed to and studied and observed the life of, saw it through movies, saw it everywhere it could be depicted. The life that existed in those other cultures. I consider myself very versed in western cultural standards, and very capable in my directing of Chekhov, Shaw, all the rest of them because it’s part of my heritage, as taught to me. There is another heritage that I have that I grew up with and my own spiritual heritage, which I don’t even know about, which reveals itself at times.

What is your advice to a young man or woman who comes to you and says: “Dean Richards, I want to make something of my life and my career. What is your advice?”

Lloyd Richards: I want to make something of my life? Or my life in the theater? Either way it’s the same thing. It’s commitment. Trust. Work. There is no substitute for work. There is no substitute for commitment. You’ve got to commit to something that you love. Invest yourself in it, and trust it.

Well, I know I asked you this, but I’ll ask one more time. Any influential books or teachers in your life, and if so, why? Anything that inspired you? Anyone who inspired you?

Lloyd Richards: I spoke of Paul Robeson, Canada Lee, I think.

Why were they influential?

Lloyd Richards: Well, you talk about taking chances, my God, Paul took so many chances in his life. What he was striving for, and insisting on, was acceptance as a human being. Not qualified by the fact of his racial origins, or national origin, but that he was a human being in the world, and should be dealt with on that basis and should be permitted to achieve, without those other really debilitating aspects becoming part of it. Canada Lee dared a lot, tried to find a lot in an atmosphere and in a world that did not make it easy. It doesn’t make it easy anyhow; art never does, but made it particularly difficult because of the specifics of this nature of the human being, as a black person, in this culture, in that time. They represented to me a kind of struggle that I was involved with, on whatever level. Whether it be in school, whether it be in terms of being on a swimming team, any of those things. They exemplified both the struggle and the achievement. The fact that achievement is never completely won.

I find it now, fighting the same battles, again and again. I’ve had to accept the fact: freedom is never won. You are always in the process of winning it. You have to do it again. The National Endowment for the Arts. What a wonderful piece of legislation that original legislation was. What a commendable thing for our government to have done to have created the National Endowment and the stipulations that were on it, the wisdom to create an area of freedom where the government or the legislature could not interfere into the work. Well, they gradually tore those barriers down, and managed to get into it, and restructure it, so that could create little pork barrels here, little pork barrels there. All of the other things that were done to disseminate the endowment.

Okay, you’ve got to go out and fight that battle again. Freedom of expression. Are we still fighting that battle? Yes. Will we go on fighting it? I assume so. Over the number of years that I have lived, those are the things that I have learned, that the most precious things are never totally won. It’s like love. It’s never totally won. It has to be worked at in order to be maintained. It’s not easy. The whole thing of casting, and non-representational casting, I was doing that 40-some years ago. We were having those same discussions, and they will go on. You keep thinking, it’s another generation, they’ve got to learn, too. They’ve got to discover, too. You don’t realize the turnover in generation, the turnover in understanding. Anti-Semitism! Astonishing! I thought we dealt with that in the Second World War! I thought we understood something when we came out of that. But there, you see it cropping up again in the very major ways that it does. We have to do that one again? All right, we will do it again. I guess that’s what life is all about. There are certain eternals, and you have to struggle to keep those eternals fresh, alive, and there for the next generation.

I can’t think of a better place to stop. Thank you. It’s been a privilege.