My interest has always been beyond buildings in isolation. It doesn’t mean to say I’m not passionate about the design of an individual building, but I can’t separate that building from its immediate environment. The idea is that it should give something back to the community of which it’s a part.

Norman Foster was born in Reddish, near Manchester, England; the family moved to the city’s Levenshulme district shortly after he was born. His father was a factory worker, his mother a waitress. Although they lacked education and sometimes struggled to support their only child, they set him an unforgettable example of tireless, uncomplaining hard work.

For as long as he could remember, Norman Foster was fascinated by design and filled sketchbooks with drawings of planes, cars, and buildings. He took inspiration from the rich architectural heritage of the city around him. Manchester’s grand 19th-century buildings testified to the city’s eminence as the historic center of Britain’s textile industry. The city’s impressive infrastructure, its rail system, and factories like the Metropolitan Vickers electrical equipment plant where his father worked fed a growing interest in engineering.

Foster was a diligent student, and at his father’s urging, he won a position as a trainee in the Treasurer’s Department at Manchester Town Hall. Further career plans were put on hold as he fulfilled his national service commitment.

Acting on his lifelong interest in aviation, he served in the Royal Air Force (RAF). His work at Town Hall had not excited him, and when he was discharged from the RAF, he disappointed his parents by turning his back on the civil service career they had planned for him. The example of a Town Hall colleague’s son had piqued his interest in studying architecture, and he landed a job as an assistant in the architectural practice of John Beardshaw and Partners. Beardshaw was impressed with Foster’s drawings and soon promoted him to draftsman.

At age 21, Foster won admission to the School of Architecture and City Planning at the University of Manchester. He worked his way through university at an assortment of odd jobs, as a baker, a nightclub bouncer, and an ice cream salesman. On graduation from Manchester in 1961, he won a fellowship for graduate study in architecture at Yale University.

At Yale, he came under the influence of the renowned architectural historian Vincent Scully. He also became friends with another British architecture student, Richard Rogers. Foster and Rogers spent a year traveling across the United States, absorbing a built environment different in many ways from that of Britain and the Continent. Already familiar with the works of European modernists such as Le Corbusier, they now had the opportunity to study firsthand the work of American architects like Frank Lloyd Wright, and European émigrés such as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. In California, they explored the Case Study houses of Richard Neutra, Rafael Soriano, Charles and Ray Eames, Pierre Koenig and Eero Saarinen, with their then-radical concept of open plan, indoor-outdoor living.

On returning to Britain in 1963, Foster, Rogers, and two architect sisters, Georgie and Wendy Cheesman, started an architectural practice of their own, known as Team 4. Specializing at first in industrial facilities, they soon acquired a reputation for innovative, high-tech architecture. After splitting with Rogers in 1967, Foster and former Team 4 member Wendy Cheesman set up a new practice as Foster Associates. Foster and Cheesman married and would have four sons.

The following year, Foster Associates embarked on a long-term collaboration with the visionary American architect and inventor Buckminster Fuller. Foster shared Fuller’s environmental concerns, and the partners pioneered energy-efficient, environmentally sensitive design. Foster also took an interest in the social experience of the people who worked in the buildings he designed.

At the time, the custom in Britain and elsewhere was to segregate workers and management, with separate entrances, dining areas, and washrooms. Foster achieved a more democratic integration of a firm’s workforce with a small building for an electronics factory. He developed the concept further in his 1969 design of a new headquarters for the Fred Olsen Line, a shipping company. Located in London’s rundown harbor district, the Docklands, he created an integrated workspace for workers and management, replete with art, a variety of dining areas and recreational facilities open to all.

Foster’s practice, up to this time, had been primarily focused on industrial facilities and had drawn little attention from a larger public. Foster’s Olsen building caught the attention of the business world, and IBM asked him to build temporary buildings while a larger headquarters project was delayed. Rather than the set of temporary huts IBM executives had imagined, Foster built a light-filled, energy-efficient building for a fraction of the cost IBM had contemplated. Completed in 1971, Foster’s IBM building incorporated the industrial facilities infrastructure into the building plan, while offering the employees natural light, fresh air, and an unprecedented freedom of movement.

The general public began to take note with Foster’s 1974 design for the new headquarters of the Willis, Faber & Dumas insurance company in Ipswich. Recalling the curving windowed facade of the Art Deco Daily Express building in Manchester, Foster took the concept a step further, creating a sweeping ground-to-rooftop glass facade, swinging in a giant irregular loop around the block. The darkened glass reflects the clouds and sky around it in the daylight hours, then grows luminously transparent as evening descends. Open plan office floors predominate within, and the firm’s workers are provided with a gymnasium, a rooftop garden and a swimming pool. These amenities were a welcome addition in underserved Ipswich, and the building became a popular venue for parties, public meetings, and civic events. Foster Associates was now considered for public buildings as well as commercial ones, such as a new art museum for the University of East Anglia in Norwich. The Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts opened in 1978 and was widely acclaimed.

Despite Foster’s growing reputation, the firm was on the verge of bankruptcy when salvation appeared in the form of a commission to build a new headquarters for HSBC (Hongkong Shanghai Banking Corporation) in Hong Kong. Foster’s design called for prefabricated steel modules to support a 47-story glass envelope from the outside, with no internal supporting structure. Eight groups of four columns each run from the foundation to the top, locked to exposed triangular trusses. Lit and heated primarily by sunlight, a bank of giant mirrors redirect light into the building’s central plaza, while exterior shades block direct light from overheating the building, which is cooled with seawater. Elevators only stop at every fourth floor, with escalators connecting the floors between stops. The floors themselves are made of movable modular panels, enabling easy access to the building’s systems — electrical, air-conditioning, telecommunications and IT. Its transparent structure allows all 3,500 workers a view of one or the other of Hong Kong’s spectacular landmarks, either Victoria Peak or Victoria Harbour. The project took seven years from concept to completion; with a price tag of $668 million, it was reputed to be the most expensive building in the world when it opened in 1985.

Foster’s professional success coincided with personal tragedy. His wife, Wendy, died in 1989, leaving him with four growing sons to raise on his own. Norman Foster was now recognized as a leading British architect. In 1990, Norman Foster was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II for his service to British architecture. The Queen herself opened Foster’s terminal building for London Stansted Airport. The building received the European Union Prize for Contemporary Architecture, known as the Mies van der Rohe Award.

The following decade was an enormously busy one for Sir Norman, as he was now known, and his associates. His firm completed new constructions, renovations, and additions for academic and cultural institutions, office buildings, harbor and rail facilities, and mixed-use complexes in Britain, the United States, Europe, and Asia. The Hong Kong International Airport, completed in 1998, was one of the largest building projects ever undertaken. The year 1999 was one of enormous achievements and highly public honors for Sir Norman. He was awarded the Pritzker Prize, often called the Nobel Prize of architecture, for his career achievement to date, and the Queen awarded him a life peerage as Baron Foster of Thames Bank.

With his firm, renamed Foster + Partners, he completed an ingenious renovation of Berlin’s historic Reichstag building, home to Germany’s parliament, the Bundestag. With the reunification of East and West Germany after the Cold War, Germans were eager to see their parliament return to its historic home, vacant since the Nazis extinguished German democracy in the 1930s. It was hoped that the renovation would celebrate the triumph of democracy and mark a break with the tragedies of the preceding century.

Foster made the building a model of environmentally sustainable building practices, expending virtually no fossil fuel while serving as an example of literal and figurative transparency. A giant glass dome above the Bundestag’s chamber allows visitors to view the workings of government from overhead and reminds the parliamentarians that the public’s eye is always upon them. The success of the Reichstag redesign led to commissions for government buildings in London, Singapore, Buenos Aires, and in Astana, Kazakhstan.

Some years earlier, Lord Foster had taken on the task of developing a new project for the heart of London’s financial district, at 30 St. Mary Axe, the site of a building irreparably damaged by an IRA bombing in 1992. Sir Norman’s proposal, the London Millennium Tower, was a 92-story structure that would have been the tallest building in Europe. A protracted public debate ensued, with preservationists objecting to the tower’s impact on London’s skyline, and Heathrow Airport authorities were concerned that it would disrupt flight paths.

Foster submitted a second proposal for 30 St. Mary Axe, a 41-story tapered ovoid wrapped with diagonal bands of glass. The ingenious structure consumes half the energy of other buildings its size. Internal airshafts draw warm air out of the building in summer and distribute passive solar heating in winter, while the wraparound windows spread sunlight throughout the building, lowering lighting costs in the daylight hours.

The Guardian newspaper had once irreverently compared Lord Foster’s 30 St. Mary Axe design to a gherkin or pickle. Londoners quickly applied the nickname “the Gherkin” to his new design for the site, completed in 2003, which has nevertheless become one of London’s most distinctive landmarks and one of Foster’s most honored achievements.

By the first unanimous vote in its history, the Royal Institute of British Architecture awarded him the Stirling Prize for “the building that has made the greatest contribution to the evolution of architecture in the past year.” A 2005 poll of the world’s largest architecture firms named it “the most admired new building in the world.” When the building’s first owner sold it in 2007, it was the most expensive office tower in Britain. It has since been sold again for even greater sums.

In the opening years of the 21st century, Lord Foster kept up the extraordinary pace of his ever-growing international practice, building an airport in Beijing; rail stations in Singapore and Bilbao, Spain; and major office buildings, including the Hearst Tower in New York City. In 2009, he began working with Apple Computer founder Steve Jobs on plans for a new Apple campus in Cupertino, California. He continued work on the project after Jobs’s death in 2011; the massive circular complex opened in 2017.

In his 80s, Lord Foster pursues a dazzling array of projects around the world. He is now exploring sustainable building solutions for the most challenging environments in the world and consulting with NASA and the European Space Agency to develop technology for building in space, on Mars, and on the Moon. He has created the Norman Foster Foundation, based in Madrid, to promote interdisciplinary thinking and assist the next generation of architects, designers, and urbanists.

In 2019, Foster + Partners’ plans for a 1,000-foot skyscraper — to be built in the heart of London’s financial district — passed the first stage of the official approval process. With the approval of the City of London Corporation’s Planning and Transportation Committee, the plan is now in the hands of the Mayor of London and the national government. The proposed building was commissioned by Brazilian banker Joseph Safra, who purchased Foster 30 St. Mary Axe (the Gherkin) for $948 million in 2014. Foster’s design — which calls for a stem-like tower topped by a glass dome — has been dubbed “the Tulip.” Foster’s design includes two sets of “gondola pods” that rotate on the sides of the building’s crown like a pair of Ferris wheels. The building will combine office spaces with restaurants, bars, a “classroom in the sky” that will host 20,000 schoolchildren a year, and a “sky bridge” that will allow visitors to slide between floors. When completed the Tulip will be the second-tallest building in London.

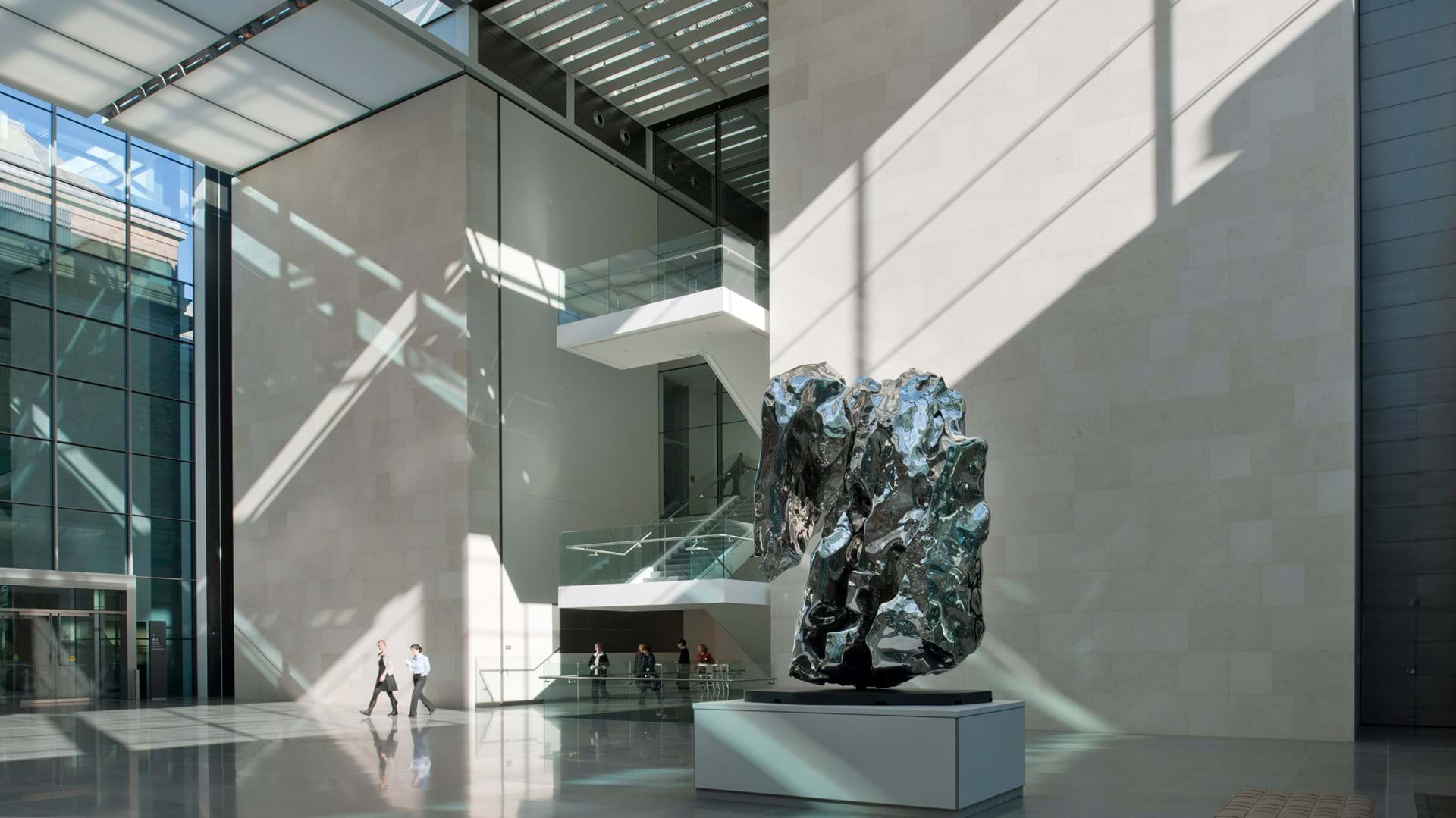

In October 2025, Foster + Partners completed JPMorgan Chase’s new global headquarters at 270 Park Avenue in New York City, a 423-metre-tall (1,388-foot), 60-story bronze-and-steel tower that now stands among Manhattan’s tallest buildings. Designed under Norman Foster’s direction, the 2.5 million-square-foot structure replaces the 1960 Union Carbide Building and serves as home to approximately 10,000 employees. The project—one of the largest all-electric and low-carbon office towers ever built—symbolizes Foster’s ongoing commitment to sustainable design and urban innovation. The building’s completion marked a major milestone for both Foster + Partners and New York’s evolving skyline in the post-pandemic era.

Lord Foster has five children and, as of this writing, three grandchildren. A second marriage ended in divorce in 1995; he is now married to publisher and art curator Elena Ochoa Foster. Vigorous and active, Foster skis enthusiastically and pilots his own jet plane to the homes he shares with Lady Foster in Britain, France, Switzerland, the United States and Spain.

Hailed as the premier British architect of our times, Lord Foster’s sleek creations in steel and glass have become landmarks of the world’s great cities, from airports in China to office towers in New York and London. He has designed the tallest bridge in the world and crowned Berlin’s Reichstag with a monumental glass dome to signify transparency in government. In 2017, Apple opened its new headquarters in Cupertino, California, a circular structure designed by Foster, working closely with the late Steve Jobs.

A working-class youth from Manchester who worked his way through architecture school, Norman Foster has received the highest honors of his profession, including the Pritzker Prize. In 1999, HM Queen Elizabeth II elevated him to the peerage as Lord Foster of Thames Bank.

Lord Foster is now collaborating with NASA and the European Space Agency to explore solutions for building habitable spaces on the Moon and Mars. He is president of the Madrid-based Norman Foster Foundation, supporting the young architects, designers, and urbanists who will build the world of the future.

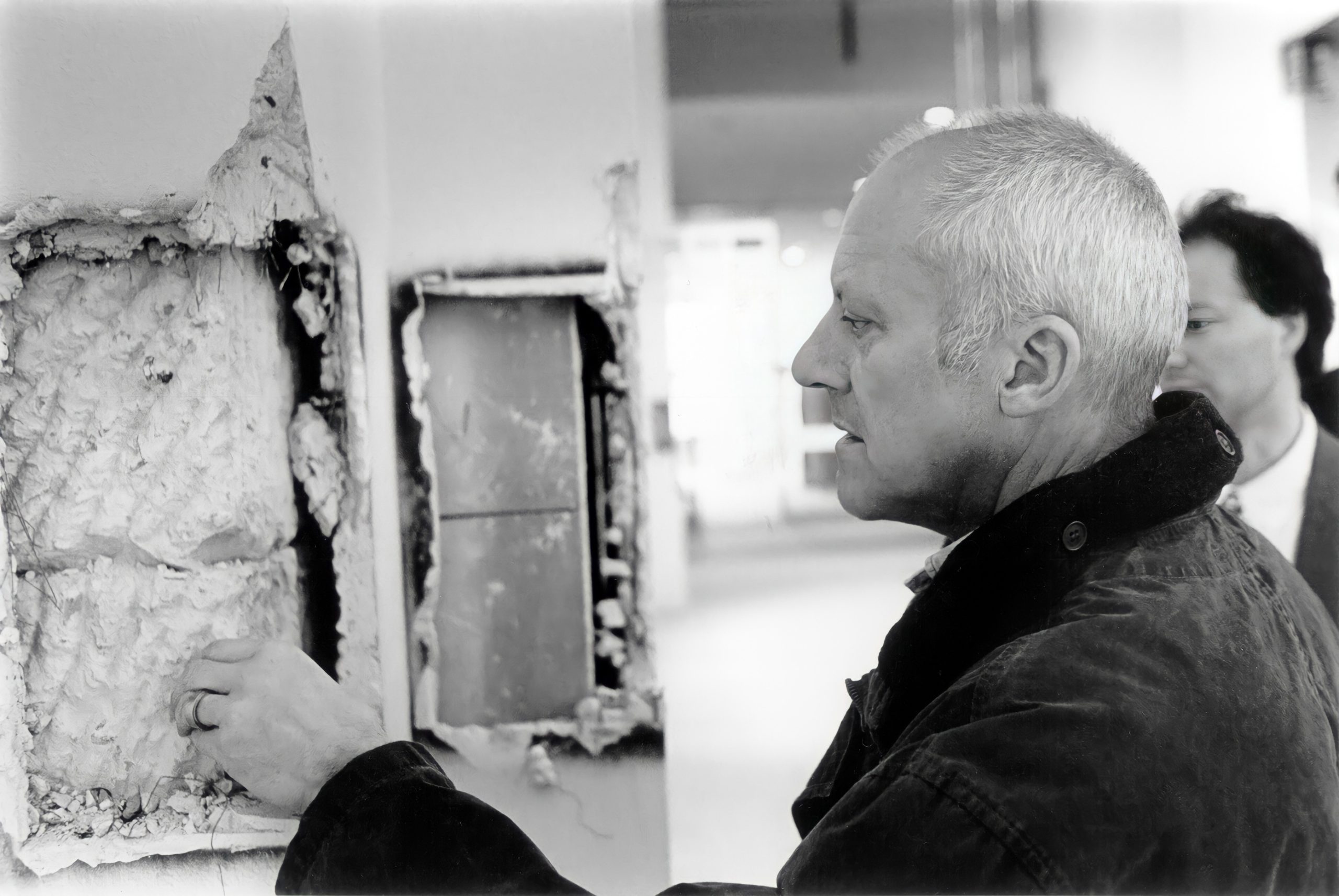

Do you remember when you first became interested in architecture?

Norman Foster: You know, from as long as I can remember, I’ve been fascinated by design in one form or another. In my foundation, we discovered in the archive a book — which I wrote in at the age of 13 and illustrated — about curtain walling. But I can remember my first sketch as a child. So whether it’s drawing or writing about design, objects, cars, racing cars, buildings, that really goes back to my early childhood.

I described this afternoon my experience of great architecture as an office boy at the age of 16. It lifted my spirits. I can still remember the details of that building. And, curiously enough, I returned not so long ago.

Norman Foster: It’s Manchester Town Hall; it’s a masterpiece by a guy called Alfred Waterhouse, 1877. And it’s heroic. It’s a noble building. It’s grand. And as you walk up the staircases, just a good experience. You have light from above. You have the stained glass. You have alcoves where you can sit. You turn a corner, suddenly there’s a soaring ceiling. It’s about the spirits. So I can remember right down to the details of the water systems in the toilets in the building. So everything was very, very special, had been considered. And I can remember walking around the streets of Manchester — this is between the age of 16 and 18 — I can remember Lancaster Arcade, on a curve with the top light. I didn’t know that it was made possible by the Great Exhibition — Joseph Paxton — of 1851, with a new vision of modernity. True high-tech architecture. I didn’t know all that, but I was moved. I was moved to visit them, and I can remember the names, even though they now, some of them, have been demolished. And I can remember that long walk out to Ancoats. I can even remember the streetscape and coming across the Daily Express Building, with the rounded corners and the glistening Vitri light and the smooth detailing. And that building moves me now — so many decades later — in the same way when I see an image or I share that image with the audience today.

But the realization of being able to be an architect, that came later. That came when I found myself in an architect’s office and I engaged with young architects. And in the conversations that I had with them, I discovered at that point that really I was much more knowledgeable on the subject than I ever thought I would be. But that had been really as a kind of private passion. Then there was the discovery that you could study architecture. That, of course, was a very, very important threshold.

When you were studying in Manchester, and then at Yale, who were the biggest influences on your own work?

Norman Foster: They were the great architects who have gone before. So they were architects like Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright. Of course, they were alive at the time that I was studying. But there were also, for me, not just buildings.

I was studying civic spaces. So I was studying the Campo at Siena. I was studying the main square in Verona, even Shepherd Market here in Mayfair, the great circus of Bath. So I was not just interested in buildings; I was interested in the civic settings for buildings, what we popularly call infrastructure, public space. I was also interested in anonymous architecture, what a scholar architect called Bernard Rudofsky was later to term “architecture without architects” — and created a very celebrated exhibition, I think in the 1960s, with a book of that name. So as a student, I was intrigued and fascinated by anonymous buildings, great barns, windmills, bridges. So my interest has always been broad and beyond buildings in isolation. It doesn’t mean to say that as an architect I’m not absolutely passionate about the design of an individual building. Of course I am. But I can’t separate that building out from its immediate environment, which may explain why, if you look at those buildings, any tall tower — the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank — it lifts it up. The public space flows underneath that building. If you take the Commerzbank Headquarters in Frankfurt, it engages with the city. There’s a shared restaurant for the citizens of the city and the occupants of the building. I could go on. So it’s more than just a building in isolation. The idea is that it should give something back to the community of which it’s a part.

Norman Foster: The examples that I’ve given are breaking down the barriers between the private world inside the building and the citizens and the city of which it’s a part. But if I go back to the very first building, it was an electronics factory conceived as a democratic pavilion. It wasn’t a management box and the workers’ shed. It wasn’t “we and they.” It wasn’t rich and poor, posh and scruffy. Everybody would use the same entrance, be under the same roof. And that was true of that small building in the London docks, which brought the dockers and the management together under one roof and generated a lifestyle. So it was about color. It was about carpet, works of art on the wall from Fred Ellison’s private collection, literally taking away the walls. And in terms of dockers, creating an incredible restaurant, ping pong, table tennis, billiards, darts. So it’s about a lifestyle.

Many of the buildings you’ve designed are now considered landmarks. What does it take to create a landmark?

Norman Foster: I think it’s working with those who commission a building to perhaps try to persuade them that it can go beyond their expectations. If I take the Reichstag — which was mentioned in passing this afternoon in the introduction — the idea that the populace could ascend through a spiral ramp to an observation platform, could occupy the roof, could have the experience of a coffee or a meal on the roof of Parliament, and could look down on the politicians below. And that this building could be a manifesto for green energy, with no fossil fuels, no pollution, zero carbon virtually. All of that was born out of convincing those politicians that this was possible. This was never part of what they asked for. But they were, in a way, encouraged, and bought into that expanded vision of the project.

You can’t really say “I’m going to make a landmark building.” I’d be very uncomfortable with that premise. I think that you can seek to strive for an extra dimension to a building, whether that is a greater public engagement or something that is going to offer some extra benefit to the people who work there or the community within which that building is placed. And sometimes that is doing something different, not for the sake of being different, but it comes out differently.

You’ve had enormously successful buildings in Asia, in Latin America, in Europe. What was the most difficult part of your professional career? Was there a time when you had to struggle?

Norman Foster: I think you’re always struggling with some issue. I think that’s life. If you’re active and you’re creative, it’s not all coasting downhill.

What’s the struggle?

Norman Foster: I think the struggles come in many forms. How you keep sharp, how you keep teams engaged and focused.

I take the aviation adage that the price of safety is constant vigilance. In other words, something which might to the outsider look easy, really it’s exceedingly difficult. And paradoxically, sometimes the simpler a building looks, the more complex the process behind it. It’s like the saying about a poem or an essay. It’s infinitely more demanding to create a poem than it is to write a long essay. And I use the analogy of the iceberg. The building — the built end product — is the tip that you see above the water. What you don’t see are the long exchanges, the process. You don’t see the designs that you’ve created, the teams, the options that have been pinned up that have been rejected. In the case of the Reichstag, you don’t see those long meetings with 65 representatives of every kind of political party who have been brought up to disagree professionally. If they’re not disagreeing, they’re not doing their job. And for the first time, they all have to agree on something. And they’re running off, and you know they’re going to the press, and you know that there’s going to be an attack in the press.

New buildings reflect changing times. There’s a great emphasis in your buildings on healthiness, in the use of light and landscape. How do you see the buildings of the future?

Norman Foster: I would say that we’re seeing all the kind of advance signals of mobility that will be much more seamless, that will be quieter, that will be cleaner, that has the potential to reduce pollution, to increase greenery in cities. If you take the revolution around transport — and it’s no longer fossil fuel-based, it’s electric — then you’re not going to have the byproducts, which are fertilizers. If you don’t have fertilizers and you have a water issue, which is also on the horizon, you have to call into question why agriculture is out there in the middle of nowhere. Because if you put it where you’ve got natural fertilizer as in sewage, and water as in waste, and you can reprocess that, recycle it, and you can use hydroponics, then your kind of garden agriculture of the future, which currently consumes a huge amount of energy and contributes to greenhouse gases, starts to come to the city. The city needs less tarmac if you follow the revolution in transport, artificial intelligence, and robotics. And if you look at surfaces — which at the moment we’re retrofitting with solar cells — if you imagine that those surfaces — that the conversion to energy is embedded in them and that you’re not retrofitting panels on top of an existing building, but the walls that you’re putting up there are going to convert light into energy, then you have, I think, some very, very exciting prospects. And cities that are more friendly, dense, less dependent on sprawl — the more compact cities, which are pedestrian friendly. London is a very good example. Manhattan is an extreme example. I mean very positive in terms of the way most people walk to work, high-quality public transport. But multiply all that with a much increased standard of mobility.

What does that look like? What’s an increased standard of mobility in a city center?

Norman Foster: I think it’s greener, it’s quieter, it’s more pleasant. It offers more opportunity, greater diversity. Paradoxically, it will offer more privacy and more community.

Why more privacy?

Norman Foster: Because it’s possible to design in such a way that you can have both. There’s a wonderful example here in London that’s over 200 years old. It’s called Albany and it was conceived at the end of the 18th century and early 19th century. That’s embedded in the middle of London. And that’s very intelligent design. So there are good examples.

As people rely less on cars, how does that figure into the shape of future living spaces?

Norman Foster: Well, maybe you just hop over the traffic. Maybe it’s vertical mobility. Maybe it’s aerial mobility. Maybe it’s an effortless transfer. Maybe the drone replaces the helicopter. Maybe the helicopter is not the prerogative of a few, but maybe it’s seamlessly interwoven into the horizontal transportation of a city.

Do you believe that there will be places to live on the Moon and on Mars one day?

Norman Foster: We’ve done two projects: one with the European Space Agency on lunar habitation, and one with NASA on habitations on Mars. And interestingly, to inhabit Mars, the Moon becomes a staging point, which makes that possible in terms of transport. I think that whole question of space travel — which arguably in its birth was out of a Cold War — but has been a vision of science fiction, and the science fiction of my youth is the reality now. So you could say that science fiction is reality waiting to happen. And in that sense, space travel is less about the idea that maybe the planet will one day be inhospitable, which it may be. But I think that is so far off. So I don’t think it’s about that. I think it’s about doing it because it’s there. Why would you climb a mountain? Why would you build a tall building? Of course, you can do all kinds of rationalizations and justifications. I can tell you statistically the benefits of building height in terms of density and the number of activities that you can get in a tall building, the way it can engage with the ground. But in the end, it’s like watching kids play or going back to our own childhood where you pile one brick on top of another. I think it’s about stretching boundaries. It’s about flight — overcoming gravity, which is still a wondrous thing. And although I’ve piloted thousands of hours in helicopters, sailplanes, fast jets, vintage biplanes, I still get a thrill from seeing an aircraft take off and land. And I think that, in a way, the whole space travel, the habitations on faraway places, is like putting up the bivouac on the side of a mountain to demonstrate you can do it initially with oxygen and then without oxygen. So I think it’s the human spirit.

Those must be fascinating discussions. How do you build with no gravity?

Norman Foster: I think there are interesting commonalities between — the principle is really the same. My foundation is working on a series of droneports across Rwanda in Africa, which will combine with the technology of the drone to be able to deliver urgent medical supplies over distances where you can’t travel by road, because that road infrastructure is not in the way that we take it for granted here, or railways. And rather than waiting for that to catch up — and in some cases, can it ever catch up, given the explosive urban growth? So it’s not just Africa. That’s true of other continents in emerging economies. So how do you combine these technologies? And the idea that really…

You don’t want to transport large masses of equipment material to remote locations. You want to work with the soil that is there. So adding an additive to the soil, making a building component and then assembling it over a prearranged form — that same principle is achieving the habitations on the Moon and Mars. You’re moving the minimum amount of mass, of weight — of stuff out there — to a faraway destination. So payload is critical. It has to be as light as possible. So you’re using the material on the Moon and on Mars. It’s called regolith. It’s essentially the moondust. And the closest that we have is volcanic ash, very, very similar. So we’ve demonstrated with these agencies that you can — in the case of the Moon, you can send out a robot. You can send out an inflatable building and inflate the building. The robot moves around. It scoops up earth. It mixes it with the additive to form a building material that will set and that will harden. The robot creates a structure, which is based on the patterns of bones in humans and animals — very, very strong crystalline structures with lots of voids. And that gets filled by the moondust; the whole thing hardens and it creates a very, very deep crust, which is resilient to meteorites, which are going faster than the speed of a bullet. They hit it — impact it — so it’s kind of sponge-like, in that sense, and easily reparable by the robot. Out in Mars, it’s the same principles, but they’re using a microwave process to melt the outer layer of the regolith. So it’s coming back to that thing of doing more with less, of higher performance.

And that is true of the mobile phone that’s in my pocket, which replaces the millions of tons of copper cable across the oceans not so long ago, and then was rendered redundant by the satellites. And then, in 1947, the power of my pocket phone would fill the entire trunk of an automobile. I remember, in the 1980s, carrying around a mobile phone, and it was a metal suitcase. I proudly put it on the table and it had the phone hook there with a kind of coiled cable.

So if you apply that approach to technology, and the reduced costs of solar, and the ability to not have heavy transmission cables, you can see the prospect of bringing power and light, clean energy, to one-quarter of the population of the world. I mean several billion who don’t have access to energy, which relates to life expectancy, infant mortality, sexual and political freedom, freedom from violence. And we haven’t even started on sanitation and clean water.

Do you spend a lot of time by yourself thinking?

Norman Foster: I still do, yes. I spend a lot of time with colleagues, a lot of time traveling. And as far as is possible, whether that is the solo pursuit of going for a bike ride or cross-country skiing — which are personal passions — then yes.

And you fly?

Norman Foster: Yes. And I sketch all the time when I —

When you’re flying low over a city?

Norman Foster: It’s a very privileged viewpoint because you’re seeing patterns. It’s no substitute for what’s on the ground, but it gives you a far more magnified — I don’t think it’s any accident that architects like Le Corbusier have been fascinated by flight, particularly in the early years. And he devoted an entire book on that subject. It wasn’t just the — I think that flight and space, the buildings that house them are generally of an epic scale. I mean you look at Tempelhof Airport, which I once described as the mother of all airports; it’s this incredible cantilever. And in a way, the cantilever is symbolic of a modern age. And the way that cantilever stretches right out so, even now, large jets can taxi underneath it. There’s that heroic dimension. And looking down on a city, you can see immediately the intelligent use of spaces. You can see the beautiful geometries and urban square row houses. You can see the sprawl. You can see the highways. You can see the strip malls, depending on where you are. In a way, it magnifies the beauty and the care and the carelessness.