I’m transcending the border of my body to connect with a greater creator collectivity. I’m transcending white or black to just be a person. I’m transcending flesh to be a consciousness. I’m transcending Earth to be part of the galaxy. I’m transcending limitations to be unlimited.

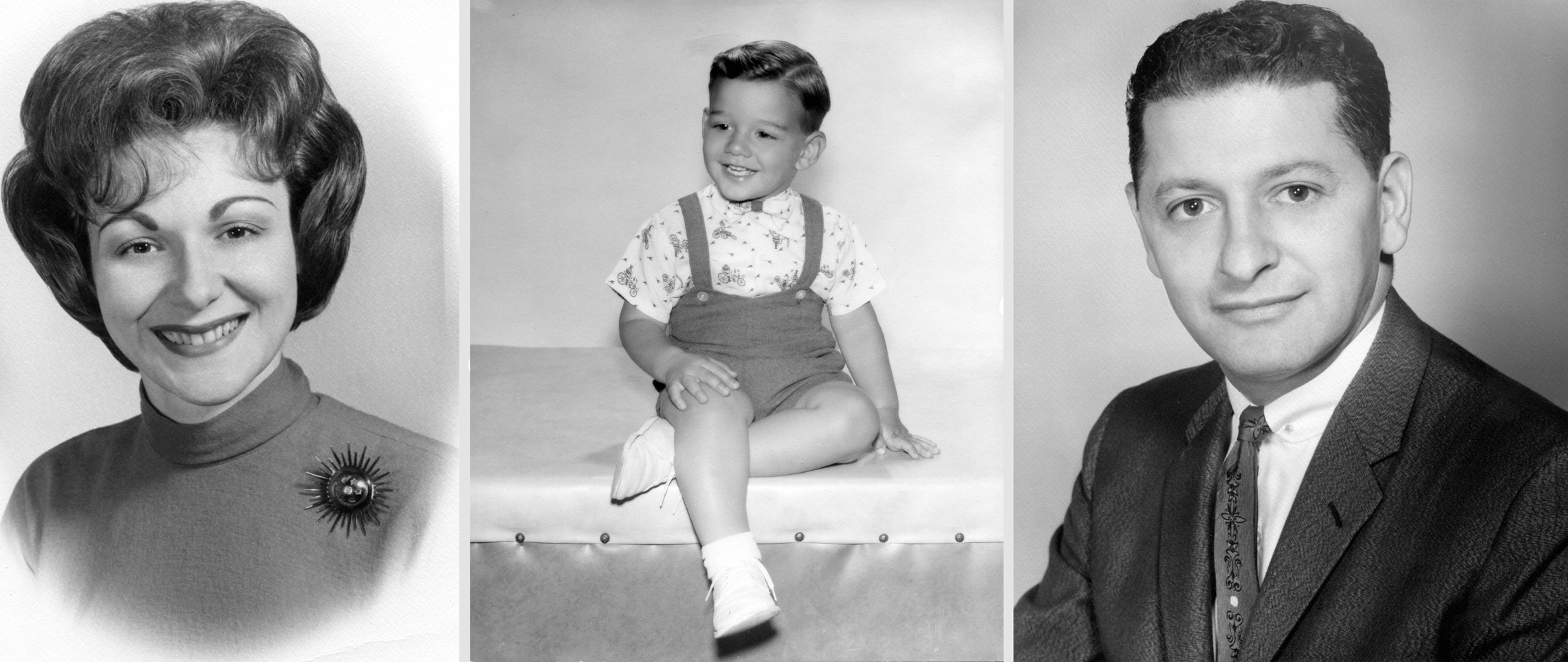

The attorney, author, entrepreneur, inventor and biotechnologist known today as Martine Rothblatt was born in Chicago, Illinois and was known for 40 years as Martin Rothblatt. The emergence of Martine as a transgender person occurred midway through a remarkable career that crosses boundaries between professional disciplines as well as traditional gender roles.

Rothblatt grew up in the Metropolitan area of San Diego, California. The secure life of the family was shattered when Martin was only five years old. The father of the family was injured in a car accident and it appeared that he would be paralyzed for life. He closed his dental practice and declared bankruptcy, fearing that he would never walk again. An experimental surgery at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota repaired the damage to the elder Rothblatt’s spine. He recovered completely and was able to resume a successful practice. From this experience, Martine Rothblatt drew the lesson that human ingenuity could overcome the most difficult challenges.

A gifted student who loved music and astronomy, the younger Rothblatt enrolled at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), but grew restless and left after sophomore year to travel and explore the world. Traveling from Europe to the Middle East and East Africa, Rothblatt arrived in the summer of 1974 on the island nation of the Seychelles in the Indian Ocean, home to a NASA satellite tracking station.

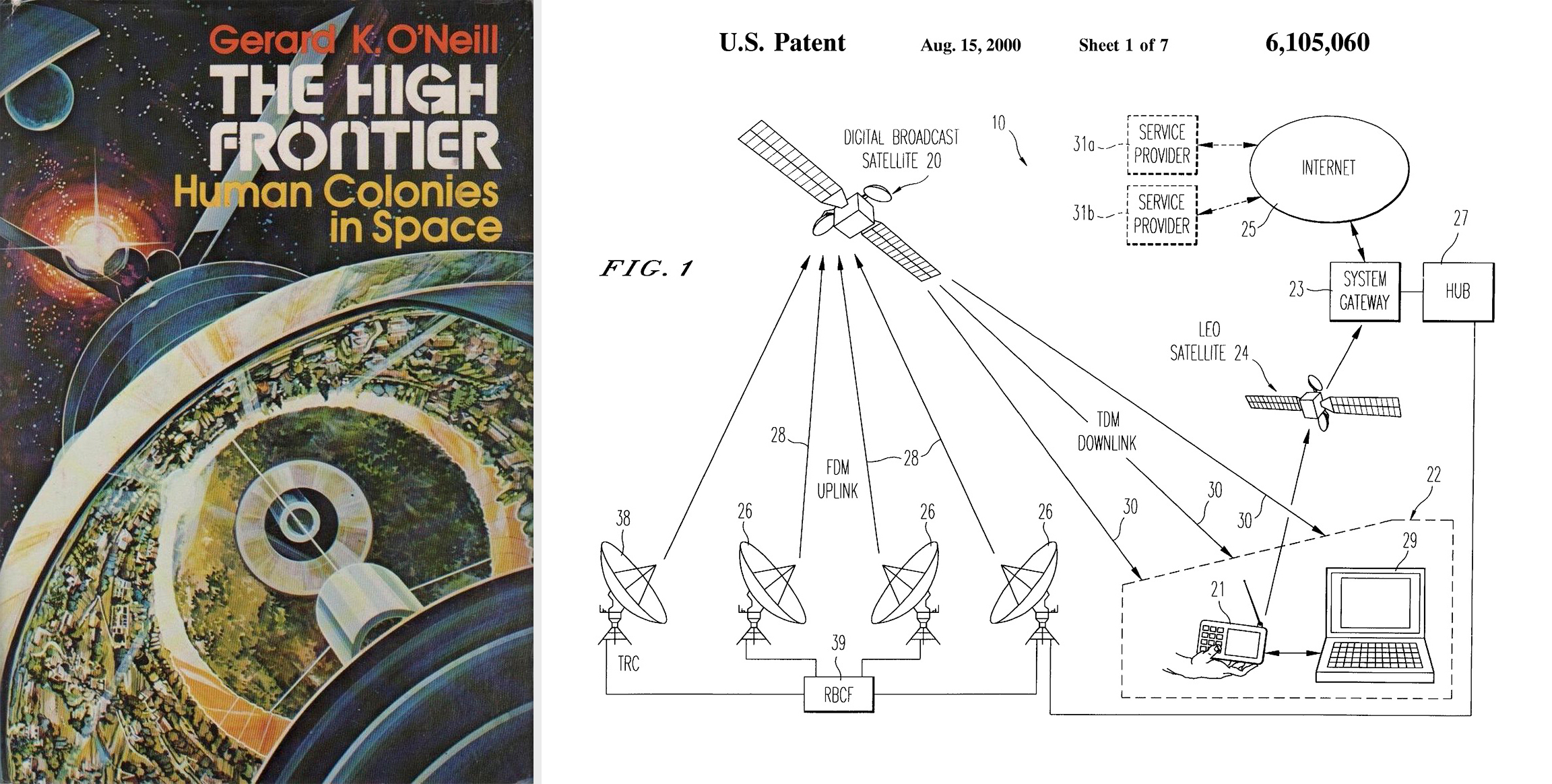

The massive spherical satellite dishes atop a mountaintop on a remote island inspired Rothblatt with a vision of a world united by satellite communications. Returning to UCLA, Rothblatt pursued a degree in communications studies. In an astronomy class, Rothblatt encountered the writings of Princeton physicist Gerard O’Neill, an advocate of space settlement and colonization. O’Neill’s book The High Frontier inspired a generation of technologists and space enthusiasts, including Rothblatt and future Amazon founder Jeff Bezos.

After graduating summa cum laude in 1977, with a senior thesis on international direct-broadcast satellites, Rothblatt enrolled in UCLA’s joint-degree program in business and law. While earning simultaneous J.D. and MBA degrees, Rothblatt set out to master the regulatory regime governing space flight and satellite communications.

While in graduate school, Rothblatt joined the Organization for the Advancement of Space Industrialization and Settlement (OASIS) and became a regular contributor to the OASIS newsletter, publishing numerous articles on the law of satellite communications. Rothblatt also prepared a business plan for the Hughes Space and Communications Group to provide communication service to Latin America. The Hughes Group did not adopt the plan at the time, but it would eventually provide the basis of the PanAmSat system.

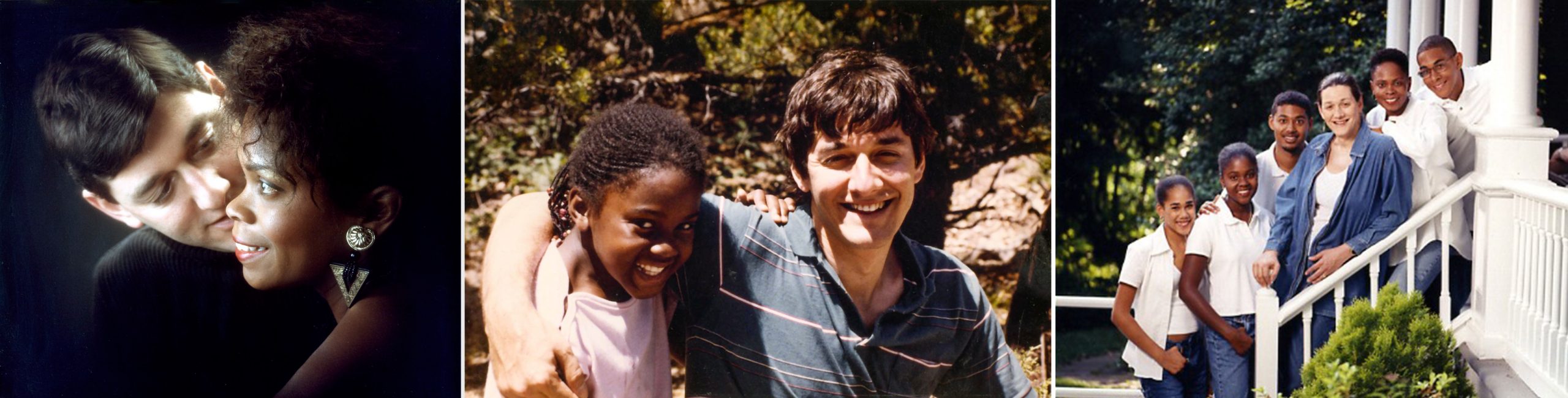

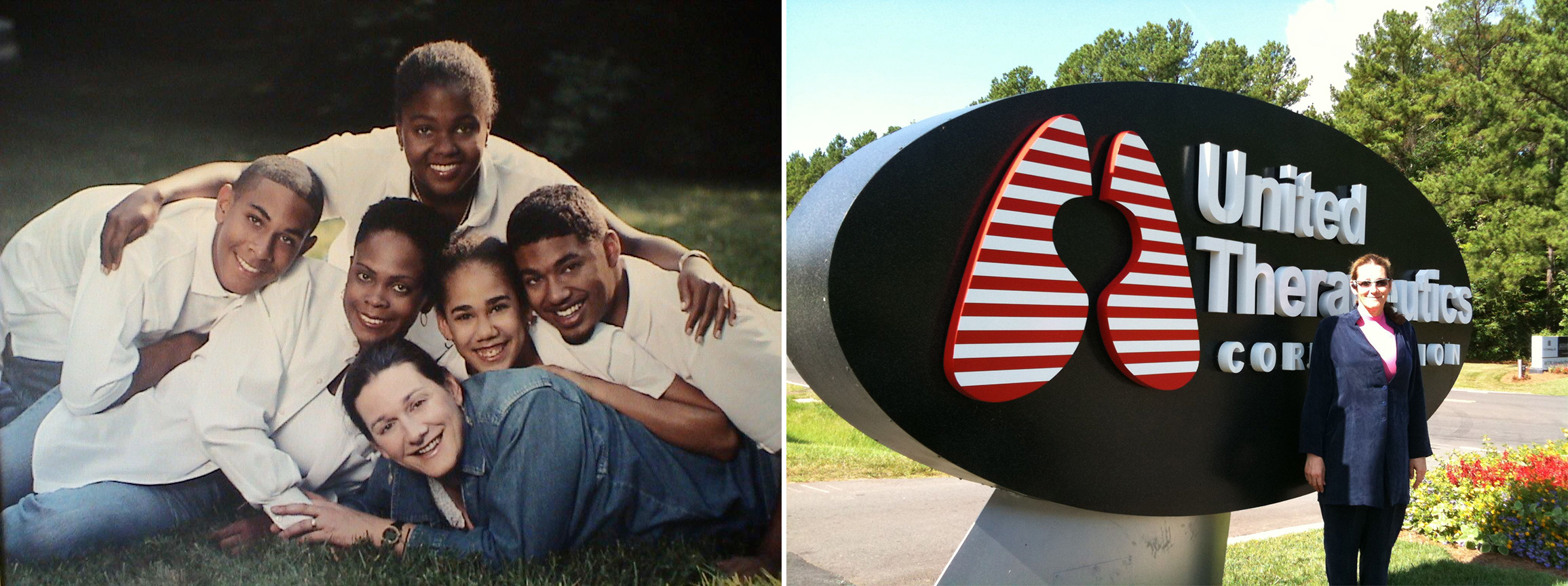

After receiving both a law degree and an MBA in 1981, Rothblatt was hired by the Washington, D.C. law firm of Covington & Burling. The young attorney was assigned to represent the television broadcasting industry before the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which regulates broadcast satellites. Within the year, Rothblatt married Bina Aspen, a realtor from Compton, California. Each had a child from a previous relationship, so they legally adopted one another’s children to form a blended family. In time they would have two more children together.

In 1982, Rothblatt left Covington and Burling, continuing to represent scientific institutions and government agencies before the FCC while studying astronomy at the University of Maryland. During this period, Rothblatt assisted the National Academy of Sciences in protecting the radio astronomy “quiet bands” used for deep space research, and advocated NASA’s interests in its tracking and data relay satellites. Gerard O’Neill, who had fired Rothblatt’s imagination as an undergraduate, retained the young attorney’s services to address business and regulatory issues for a new system of satellite navigation technology he had developed. Known as Geostar, the new system enabled precise location tracking of aircraft, but Rothblatt foresaw a more expansive use of the technology.

The PanAmSat system Rothblatt had first proposed in graduate school was taken up by the founder of Spanish International Network and with Rothblatt’s assistance became the first private international space-based communications system, a successful competitor to the longtime monopoly Intelsat. PanAmSat would provide the foundation for the international Spanish-language television network Univision.

In 1986, Rothblatt discontinued private law practice and astronomy studies to become the full-time CEO of Geostar. During this time, Rothblatt led successful efforts to win international agreements for the allocation of satellite orbits and spectrum frequencies for space-based navigation services. The Geostar Satellite System enabled geolocation tracking of aircraft, but Rothblatt foresaw a more expansive use of the technology.

Meanwhile, the PanAmSat system Rothblatt had first proposed in graduate school was taken up by the founder of Spanish International Network and with Rothblatt’s assistance became the first private international space-based communications system, a successful competitor to the longtime monopoly Intelsat. In addition to satellite-based telephone services, PanAmSat would provide the foundation for the international Spanish-language television network Univision. In 1986, Rothblatt discontinued private law practice and astronomy studies to become the full-time CEO of Geostar. During this time, Rothblatt led successful efforts to win international agreements for the allocation of satellite orbits and spectrum frequencies for space-based navigation services, and eventually for direct-to-person satellite radio transmissions.

Working with Geostar confirmed Rothblatt’s perception that satellite radio services could be used for many other purposes besides locating aircraft. In 1990 Rothblatt left Geostar to create two new companies: WorldSpace and Sirius Satellite Radio. WorldSpace became the first global satellite radio network, while Sirius provided commercial-free music and information broadcasts directly from satellites to its users’ car radios. Rothblatt deftly persuaded FCC commissioners to grant the necessary licenses by designing Sirius as a subscription service rather than an advertiser-supported commercial network. Sirius operates a small fleet of satellites, enabling listeners to tune into the same stations anywhere in the United States. The system also gives pilots instant access to real-time weather information, a great step forward in air traffic safety.

The music, news and information services provided by SiriusXM, as the company is now known, were an enormous success. Rothblatt stepped down as Chairman and CEO in 1992 but remained a major shareholder. When the company went public two years later, Rothblatt enjoyed a significant financial windfall. At this point, Rothblatt had made enough money to provide for a growing family and enjoy a very comfortable retirement, but the following years would bring great changes and harrowing challenges.

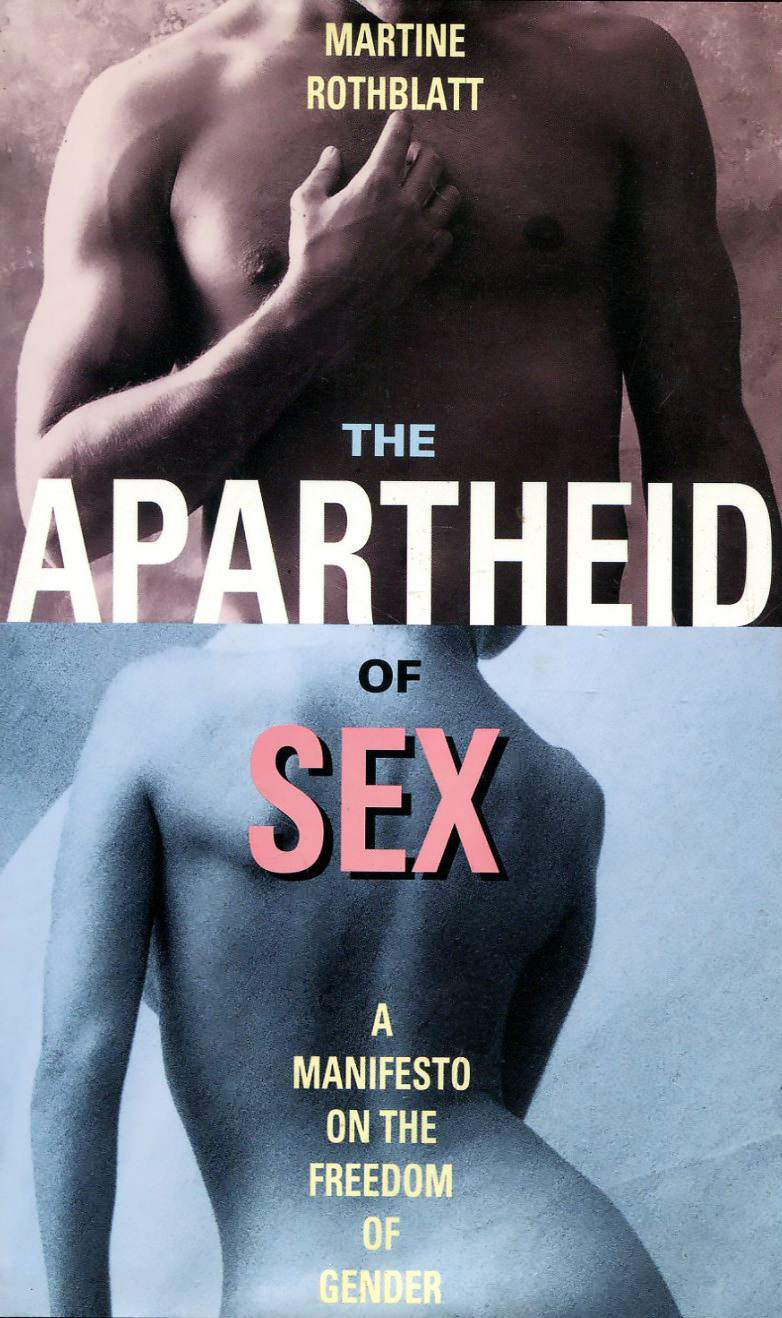

At age 40, Rothblatt underwent sex reassignment surgery and in 1994, publicly identified for the first time as transgender, changing her legal name to Martine Aliana Rothblatt. As Martine, she has become a vocal advocate for transgender rights and has led efforts to establish appropriate health law standards for the transgender community, and to resist discriminatory legislation. Martine Rothblatt has shared her thoughts on gender and identity in her 1995 book, Apartheid of Sex: A Manifesto on the Freedom of Gender.

In the same year that Martine Rothblatt announced a public redefinition of her identity, she confronted an experience every parent fears. Her seven-year-old daughter Jenesis was diagnosed with primary pulmonary hypertension (PPH), an incurable malady of the lungs that her doctors predicted would end her life within a few years. Determined to explore every option that could save her daughter’s life, Rothblatt created the PPH Cure Foundation to mobilize research efforts.

Suspending her business concerns, Martine Rothblatt set out to learn everything she could about her daughter’s illness, giving herself a crash course in biology, a subject she had last studied in 10th grade. Her research quicky led her into the complex issues around organ transplantation, particularly the use of animal organs in human medical treatment (xenotransplantation). Rothblatt undertook a doctoral course in medical ethics at the London School of Medicine and Dentistry, commonly known as Barts (for St. Bartholomew’s Hospital), part of the University of London system. Frustrated with the slow pace of the search for a cure, and confident that she could manage a superior research effort, Rothblatt founded a new medical biotechnology company, United Therapeutics, in 1996.

Meanwhile, Rothblatt’s activities in telecommunications continued to bear fruit. She helped pioneer airship internet services with her Sky Station project in 1997, persuading the FCC to allocate frequencies for airship-based internet services. The same year, she left the last of her telecommunications commitments, leadership of WorldSpace, to become the full-time Chairman and CEO of United Therapeutics.

Over the next few years, United Therapeutics developed Orenitram, an effective medication for pulmonary hypertension. Jenesis Rothblatt grew to adulthood and became an executive with the business that had saved her life. Thousands who would have otherwise died are now living and using this medication. Since then, the company has created a treatment for neuroblastoma, a cancer that most often arises in the adrenal glands. This too has saved thousands of lives. United Therapeutics is now pursuing methods to manufacture a virtually unlimited supply of substitute organs for transplant. These methods include repairing donated organs previously considered too damaged for transplant, and xenotransplantation — adapting animal organs for human use.

In her 1997 book Unzipped Genes, explored the legal, ethical and political issues arising from the sequencing of the human genome. She led the International Bar Association’s project to draft a Universal Declaration on the Human Genome and Human Rights for the United Nations, officially adopted by the by the United Nations General Assembly in 1998. Martine Rothblatt was awarded her Ph.D. in medical ethics in 2001. Her dissertation was published in 2003 as Your Life or Mine: How Geoethics Can Resolve the Conflict Between Private and Public Interests in Xenotransplantation.

Dr. Rothblatt’s interests continued to grow beyond law, technology and medicine into ever larger questions. In 2004, Rothblatt launched the Terasem Movement, “a transhumanist school of thought” exploring the prospect of “technological immortality” via mind uploading and geoethical nanotechnology. She elaborated on these ideas in her 2011 book From Transgender to Transhuman: A Manifesto on the Freedom of Form, and on artificial intelligence in Virtually Human (2014).

United Therapeutics prospered, and by 2013 Dr. Rothblatt was reported to be the highest-paid female CEO in America, based on the value of the stock options in her compensation package. In 2017 Forbes magazine named Rothblatt one of the “100 Greatest Living Business Minds” of the past century, citing her achievements as a “perpetual reinventor, founder of Sirius and United Therapeutics, and creator of PanAmSat.”

As United Therapeutics continued its quest to manufacture an unlimited supply of organs for transplant, Rothblatt gave more thought to the timely delivery of transplant organs — often a matter of life and death — in an environmentally sustainable way. Drawing on her expertise as a licensed airplane and helicopter pilot, she set out to develop and manufacture an electric helicopter, powered by batteries that could be charged from a renewable energy source. The first EPSAROD (Electrically Powered Semi-Autonomous Rotorcraft for Organ Delivery), took flight in 2016. Through a United Therapeutics subsidiary, Lung Technology PBC, Rothblatt continued to support research in eVTOL (electric vertical takeoff and landing) technology, and in 2018 personally set a world’s record for speed, altitude, and flight duration in an electric helicopter.

The same year, Rothblatt opened a new headquarters for United Therapeutics in Silver Spring, Maryland. Called the Unisphere, at 210,000 square feet of space it is the world’s largest site net-zero (carbon-neutral) office building. Heated and cooled entirely by on-site sustainable energy, it is equipped with a million watts of solar power, 52 geothermal wells, and a subterranean labyrinth to store excess energy. Electrochromic glass windows and partitions brighten and darken to control light and heat, while giving the occupants a graphic demonstration of the building’s net energy use.

Martine Rothblatt regularly discusses her thoughts on “the coming age of… cyberconsciousness and techno-immortality” in her blog Mindfiles, Mindware and Mindclones. Collaborating with Hanson Robotics, Rothblatt has created a humanoid robot modeled on her partner Bina, programmed to reflect Bina’s memories, feelings and beliefs. Called BINA48, “one of humanity’s first cybernetic companions” can sit for interviews and has completed a college-level philosophy course. Rothblatt has also created a website Lifenaut.com as a place where others can upload their thoughts to create “cybernetic doubles” of themselves.

Cited as one of Business Insider’s “Most Powerful LGBTQ+ People in Tech” in 2018, Rothblatt was awarded the UCLA Medal, the university’s highest honor, in recognition of her creation of SiriusXM satellite radio, advancing organ transplant technology, and having “expanded the way we understand fundamental concepts ranging from communication to gender to the nature of consciousness and mortality.”

In September 2021, United Therapeutics subsidiary Unither Bioelectronics completed the world’s first drone delivery of donor lungs for transplant from Toronto Western Hospital to Toronto General Hospital — symbolic as the site of the world’s first single and double lung transplants. Unither Bioelectronics, led by United Therapeutics CEO Martine Rothblatt along with Mikaël Cardinal, VP of program management for Organ Delivery Systems, said it has “established an important stepping stone for future organ delivery” that will ultimately open the door for widespread adoption of larger, longer-range, autonomous eVTOL aircraft.

In October 2021, for the first time, a pig kidney was transplanted into a human without triggering immediate rejection by the recipient’s immune system, a potentially major advance that could eventually help alleviate a dire shortage of human organs for transplant. The procedure done at NYU Langone Health in New York City involved use of a pig whose genes had been altered so that its tissues no longer contained a molecule known to trigger almost immediate rejection. The genetically altered pig, dubbed GalSafe, was developed by United Therapeutics Corp’s Revivicor unit. It was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in December 2020, for use as food for people with a meat allergy and as a potential source of human therapeutics.

On January 7, 2022, Dave Bennett, a 57-year-old man with terminal heart disease, was implanted with a genetically modified pig heart provided by Revivicor in a first-of-its-kind surgery. The surgery, performed by a team at the University of Maryland Medicine, is among the first to demonstrate the feasibility of a pig-to-human heart transplant.

In June 2022, at the LIFE ITSELF conference in San Diego, United Therapeutics showcased 3D printed lung scaffolds that are now demonstrating gas exchange in animal models. Together with 3D printer manufacturer 3D Systems, Rothblatt said they “are regularly printing lung scaffolds as accurately as driving across the United States and not deviating from a course by more than the width of a human hair.

Martine Rothblatt’s patented inventions span the fields of satellite communication, medicinal biochemistry and cognitive software. As the founder of the satellite radio network SiriusXM, she had already revolutionized the fields of communications and broadcasting, when her seven-year-old daughter fell ill. Doctors diagnosed pulmonary hypertension, an incurable lung disorder, and gave the child little chance of surviving to adulthood. This unexpected crisis led to an abrupt career change.

Setting aside her past business commitments, Rothblatt gave herself a crash course in medical science and founded a new company, United Therapeutics, to find a treatment that could save her daughter’s life. Since then, the company has developed successful treatments for pulmonary hypertension, as well as for the cancer neuroblastoma.

Martine Rothblatt’s books and published writings range over subjects from gender identity to the concepts of “mind uploading” and “technological immortality.” She has been repeatedly cited as the highest-paid executive in the biopharmaceutical industry and the highest-paid female chief executive in the world. Today, she is Chair and CEO of United Therapeutics, and her adult daughter works alongside her.

We’ve read that you became interested in space travel and colonization while you were in college. How did you follow through on that?

Martine Rothblatt: I became a writer and a member of an organization called the Organization for the Advancement of Space, Industrialization, and Settlement. It’s a mouthful so we went by the acronym OASIS, which is what those letters break down to. It was an organization started by a physicist at Princeton named Gerry O’Neil. And to show you how — it’s funny how — my thing I love most of all, when things come full circle in a positive way. So we were just talking about Jeff Bezos a moment ago. So last year, he kind of came out and said that the reason he founded Amazon and the reason he’s done all of these things to build it up and form Blue Origin and everything was because he was a student of Gerry O’Neill’s at Princeton in the ‘80s and read about Dr. O’Neill’s ideas for moving most of humanity into space. And he decided that that was his purpose in life, and it was just like, “How do I make that practically happen? Start with Amazon and then Blue Origin.”

And you started Sirius XM Satellite Radio. How did you come up with that idea?

Martine Rothblatt: I had, previously, was responsible for another type of satellite communication system where we would track the locations of vehicles. That system was actually invented by Dr. O’Neill. As I got to know him and we shared our vision for building cities and space settlements and space, he said, “Martine, I’ve come up with this idea for using satellites to locate objects on the earth…” — this was before GPS — “…and I believe that this can help eliminate planes crashing into each other, vehicles getting lost or stolen. It could be more efficient for people. People could find their ways around. Would you be willing to take this idea and get the government to approve it, raise the money for it and make it happen?” So I said like, “Yes, Dr. O’Neill, I will,” because he was my hero. As he was Jeff (Bezos)’s hero, he’s an amazing person. So I did that, and we did launch those satellites and tracked thousands of vehicles and tracked planes. Actually, those satellites are still operating today. But that’s… I was doing that. I said, you know, the same signals of sending latitude and longitude could be used for sending music. And it would be a way to connect, to be able to listen to the same channel while you travel the hundreds of miles instead of constantly changing. It would be a way to get the kind of channels that I personally love, which are jazz mostly, be able to get these channels outside of New York or Los Angeles and anywhere in the country.

How did you make that leap from tracking airplanes to broadcasting music and information programming?

Martine Rothblatt: Well, I’m an amateur musician. You know, I play keyboards and flute. So I’m deeply into music and I’m running this company that’s using satellites to track vehicles. I had previously been involved in getting the FCC to approve satellites for television broadcasting so it was kind of logical to say, “How can I combine satellites for television broadcasting with satellites to track things moving around?” You don’t need to watch TV while you’re driving, but you do need to listen to music or now podcasts. So it was, I think, a natural logical evolution.

One of the breakthroughs with Sirius was the breadth of programming. You could hear almost anything you wanted with better reception and no commercials. How did you decide on that?

Martine Rothblatt: I personally don’t like commercials. So I’m like a channel surfer. When the commercial comes on, I’ll surf right past it. I used to mostly listen between 88 to 92 megahertz, because that’s like the non-commercial band. You’ve got to remember that my original, original training is I’m basically what they call a spectrum manager. I worked with the FCC to get frequencies of the electromagnetic spectrum set aside for new services. So I am a spectrum geek is a fair thing to say. So I knew there was a need for content without commercials.

Secondly, I knew there was a need for the content that we have in big cities like New York in all the other places in the country. So I said, “How can I go about doing that?” There was no more room on the AM and FM radio band. But I knew as a spectrum geek that there was millions of more spectrum than between AM and FM that could be transmitted by satellite because those frequencies were not used for other things and they passed through the atmosphere.

So I studied the physics of it. I designed the satellite communication system. I found the radio frequencies that would pass through the atmosphere and pass through like the leaves in the trees — places like Rock Creek Park and whatnot — as good as possible. There’s a lot of just “devil is in the details” issues, like when it rains leaves absorb more frequencies when they didn’t. I pulled all this together, I went to the FCC, which I knew because that was my business, that was my career. I said, “I propose we create a satellite digital audio radio system,” which is the technical name for Sirius XM.

What did they say?

Martine Rothblatt: “No,” they said. The first thing they said is, “It won’t work.” They said, “Won’t work.” That was the very first thing they said. So I built a system. I don’t know if you remember, there used to be… USA Today was the tallest building across the Potomac. So I put a pseudo-satellite transmitter on top of that building that had the equivalent power of a satellite in space. And WPFW used to have a station on H street right near Chinatown where it is right now. So I went into their studios, because our offices were in Tech World right around the corner from there.

I brought the FCC people into my car and I drove them all around downtown Washington and I showed them that no, satellite communications does work. So they said, “Okay, it works. Secondly, any frequencies that you want are going to have to be taken away from somebody else because the military uses all these frequencies and television news gathering trucks use these frequencies…” All the frequencies are being used by somebody or another, but mostly they’re not being used very efficiently.

So I then created a grass roots movement of rural organizations. A lot of them were search-and-rescue type organizations who would benefit from having 24 hours of content being broadcast all the time by satellite, including aircraft in flight. And I had over 300 grassroots organizations in turn, including community groups in places like Oklahoma and Nebraska. I proved, because the law says the FCC is supposed to allocate the radio frequencies, quote unquote, “in the public interest.” So I said the public interest is to have the same diversity of programming in big cities everywhere in the country. Satellites can do it. Then they said, “Well, it’s not legal for one company to control 100 channels across the entire country.”

In fact, it wasn’t even legal for one company to control more than three channels in any one city. So I said, I had to come up with an entirely new concept for them. I said, “Well, that’s true if it’s free. But what if we make people pay for this?” And they’d never thought of that. They said, “Well, that’s something completely different.”

Because it’s on a subscription basis?

Martine Rothblatt: It is subscription based. That gave me the business model that I needed.

How do you go about finding frequencies? What does that look like?

Martine Rothblatt: So what that looks like is the government publishes a chart and the chart shows all of the frequencies and it’s separate from the lowest frequencies in the kilohertz range to the highest frequencies in the gigahertz range. And every use, such as police radio or wireless garage door openers or the television trucks that have the antennas that pop up and beam car accident footage, every single use — jet planes to pilots to control tower, military demo — is a use approved by the government. And then these charts, they’re each given a different color, and because there’s so many different uses even run out of colors so they start making hashes and dots and stuff. So this is called a chart of the electromagnetic spectrum. And I know that chart as well as somebody would know the map of the U.S. and the 50 states.

Sirius was successful but then you ran into a major health crisis in your family. Can you tell us about that?

Martine Rothblatt: At first we didn’t know what was wrong with our daughter, Jenesis. And when a doctor comes in and says he’s only seen less than five patients with this; they all died. They’re all kids. All he can recommend us to do is to meet with the transplant coordinator, but not to hold out hope that we’re going to find a lung transplant for a person as small as a five-, six-year-old kid. We were both crying and nothing mattered to me. But still, I never thought that I personally could come up with a medicine because it wasn’t my field. And I think if there’s any lesson from my life that can be learned is that don’t think there’s anything that you cannot do.

So fast forward, and now you’re one of the most admired CEOs in all of biopharmaceutical work. How did that happen?

Martine Rothblatt: What happened, in fact, was I said, “Let me find anybody who’s working on this disease.” There were only 20 people in the whole U.S. who are working on it because everybody died of it. And I said I did have financial — money — resources from taking Sirius public. So I said to them, “Look, I’ll give you grants if you can come up with a medicine for my daughter.” They took the grants, they never came up with anything. I contacted all the major pharmaceutical companies. They said, “We’re not interested in this disease, it only affects 2,000 people. Finally, one doctor said, “You know, Martine, I think you can if you want to save Jenesis, you’re going to have to do it yourself.” And I said myself, “I don’t know anything about biology.” They said, “You could figure that out, you’ve launched these satellites.” And that’s when the light turned on in my head. They said, “If you don’t do this, Jenesis is not going to make it.”

How old was Jenesis?

Martine Rothblatt: She was seven at that time. So I said, “Okay, let’s forget Sirius, forget satellites. My purpose in life is just to save Jenesis. So I taught myself biology, I taught myself everything about this.

How? Did you just get books and start reading?

Martine Rothblatt: Fortunately, Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, D.C. — I know where you know where it is on Michigan Avenue — my daughter was there week after week after week, and I was there with her. And they had a great — a great — library. They have things like card catalogues and reader’s guides that fortunately, us being kids of the ‘60s, we knew what they were.

So I was able to use those tools, read the books, read the journal articles. I read a journal article, I wouldn’t understand it, so I go to the dictionary. Look up the words I didn’t understand, I’d go back to the journal articles. I’d find like a high school biology book then a college anatomy book. I just kept going back and forth until I could understand.

I think what I can do is I can pick out the important parts of descriptions of knowledge much more efficiently than most people can. I can separate the wheat from the chaff. Like, if there’s a peer-reviewed journal article, most people will try to read the whole article, okay. That will take a long time. They may fall asleep doing it. They may get a headache from doing it.

I can look at this whole article and say, you know, these three paragraphs out of maybe like 100 or 200 paragraphs have the meat of the article. So I’ll digest those three paragraphs and then I’ll look in the references at the back of the article and I’ll go pull every article that that article referenced. And they do that until I’ve reached like a point of diminishing returns where I’ve digested everything on the field.

So for the rest of us who want to be more efficient, tell us a couple tips for doing that.

Martine Rothblatt: Don’t worry about the details. That’s it. It’s really as simple as that. Just skip the details. Focus on like the 30,000-foot view.

What is that in this case?

Martine Rothblatt: So the 30,000-foot view that I realized from reading these articles in the case of my daughter is that the pulmonary artery, which is the artery that takes blood from the heart to the lungs, is different from every other artery in your body, which is kind of interesting.

The reason it’s different from every other artery in your body is arteries take blood from the heart, veins take blood to the heart. So all of the other arteries in your body take blood, which is full of red blood cells that have been freshly oxygenated. So when your heart pumps, all your body gets freshly oxygenated blood. So those arteries respond to the blood cells that have fresh oxygen.

Except the pulmonary arteries take blood from your heart, but it takes it to your lungs to get oxygenated. So those arteries are different. They are the only arteries in the body that carry de-oxygenated blood, blood full of the carbon dioxide that we get from our respiration cycle. So I said those arteries must be different, must be biochemically different than any other artery. And if I can find a molecule that will speak just to those arteries, I can open up those arteries and leave all the rest of the arteries alone.

Is that the medicine you eventually found?

Martine Rothblatt: That is the medicine. And that’s a 30,000 foot view, that’s not talking about long names of molecules and stuff like that. That’s just, “I want a molecule that’s going to talk to these arteries that are different because they carry de-oxygenated blood.”

So does your company make this medicine?

Martine Rothblatt: We make this medicine.

How old is your daughter now?

Martine Rothblatt: She’s 32. She works in our company. She’s delightful. I love She knows that.

How many other lives do you suppose your company has saved?

Martine Rothblatt: Well, we know that over 50,000 people are living with pulmonary hypertension. And when she was diagnosed, only 2,000 were because they all died.

How does that feel?

Martine Rothblatt: Don’t think that there’s anything you cannot do.

What is something you want to make sure you do before you die?

Martine Rothblatt: Create an unlimited supply of transplantable organs.

Why did you pick that?

Martine Rothblatt: I picked that because I think it picked me, to be frank. One reason I picked it is because I know I can achieve it. I feel it’s realistic, I can achieve it. I feel I’m probably the — it sounds arrogant, but I think it’s kind of a fact — I think I’m probably the only person in the world that can make that happen a few decades sooner than it would happen otherwise. And it’s because I have the resources to do it, I have bit by bit built the teams of scientists who are most confident of doing it. I have the motivation and passion to do it because I am convinced that not only my daughter, but the thousands of people who take our medicines will eventually need a transplant.

What organs are we talking about?

Martine Rothblatt: Lungs, livers, kidneys and hearts.

So thousands of people will live longer?.

Martine Rothblatt: Millions.

That would be a pretty good legacy.

Martine Rothblatt: I don’t even think about it like that. To me, that’s an honor to have that legacy. It’s my purpose in life.

I didn’t ask to be in the biology field, but life brought me there. So now I’m here, I’m going to be the absolute best biotechnologist I can be. And the particular field that’s been set before me is organ transplantation. So I will achieve that before the end of the decade. And I’m equally adamant that I do that in a green fashion. That I do that from buildings which have zero carbon footprint and with the organs delivered by helicopters that also have zero carbon footprints.

You think so big. What advice would you give to those listening who also want to do big things?

Martine Rothblatt: I would say don’t focus on my big thinking, focus on my practical doing. So like a million times more important than my big thinking is that practical doing. In 1990 I said that I would launch a satellite radio system that would provide 100 channels of non-commercial programming throughout all of North America, and it was launched in 2000.

By 2000, I said, I would, I say, if it was the last thing I do in my life I would develop a medicine to save Jenesis. Okay, developed that medicine and actually had the three of them approved by 2010. In 2010, I said before the end of the teens, before the end the twenty-teens, we would manufacture an organ and bring an end-stage lung disease patient back to life.

It’s now 2019, and we’ve brought hundreds of end-stage lung disease patients back to life with manufactured organs. And now in the 2020s, before the end of this decade, I said I would like to develop an unlimited supply of manufactured organs and have them delivered by zero carbon EVTOLs —“electric vertical takeoff and landing” — electric helicopter aircraft. And that is the purpose of my life during the 2020s. Other than just reading, playing music, looking at stars and hanging out with Bina!