I think human beings have an innate desire to help each other. And whether you're in medicine or anything else, if you see someone that you can help...you get a gratification from doing it. In fact, I think that is perhaps the most important, you might say, fabric that holds the society together.

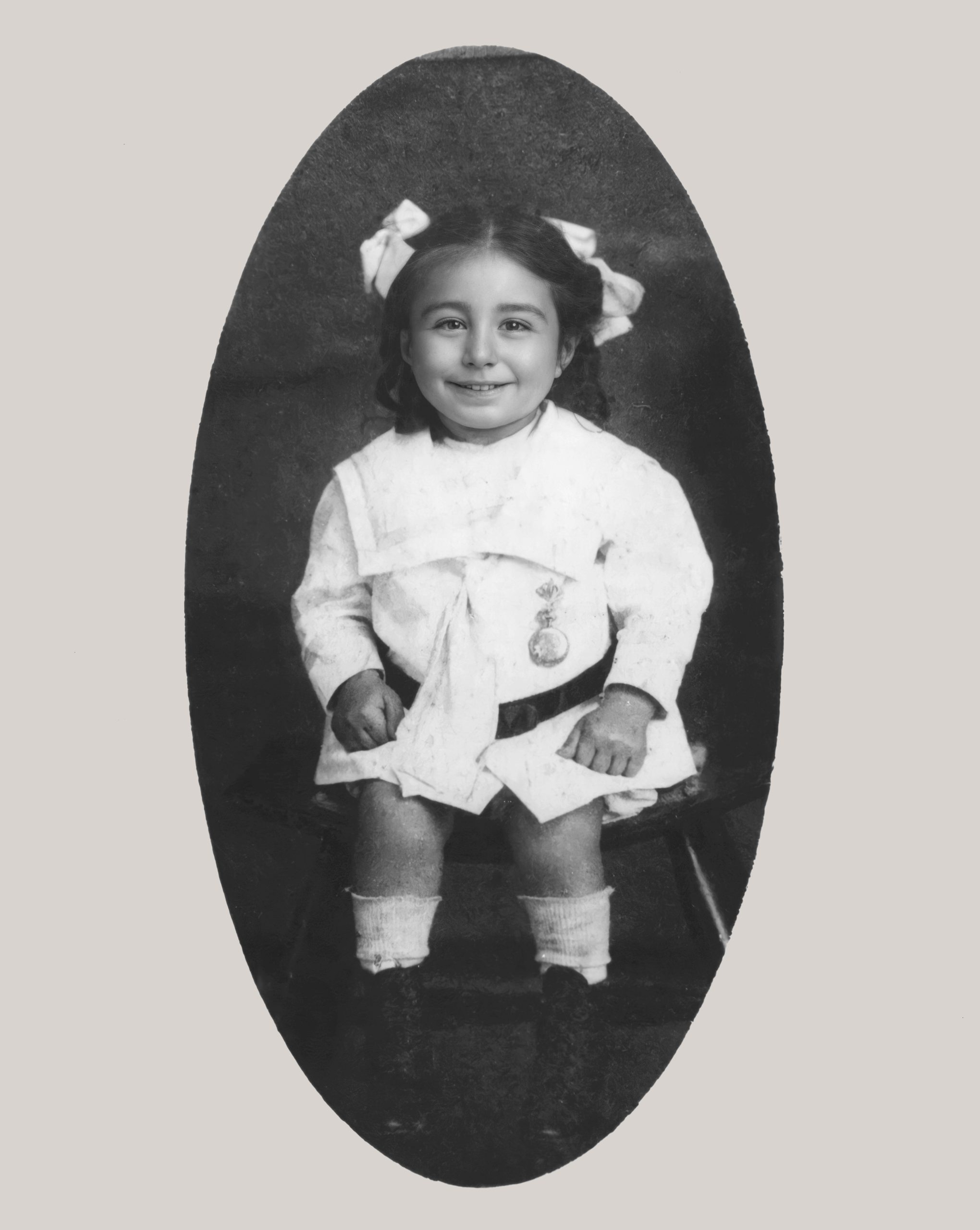

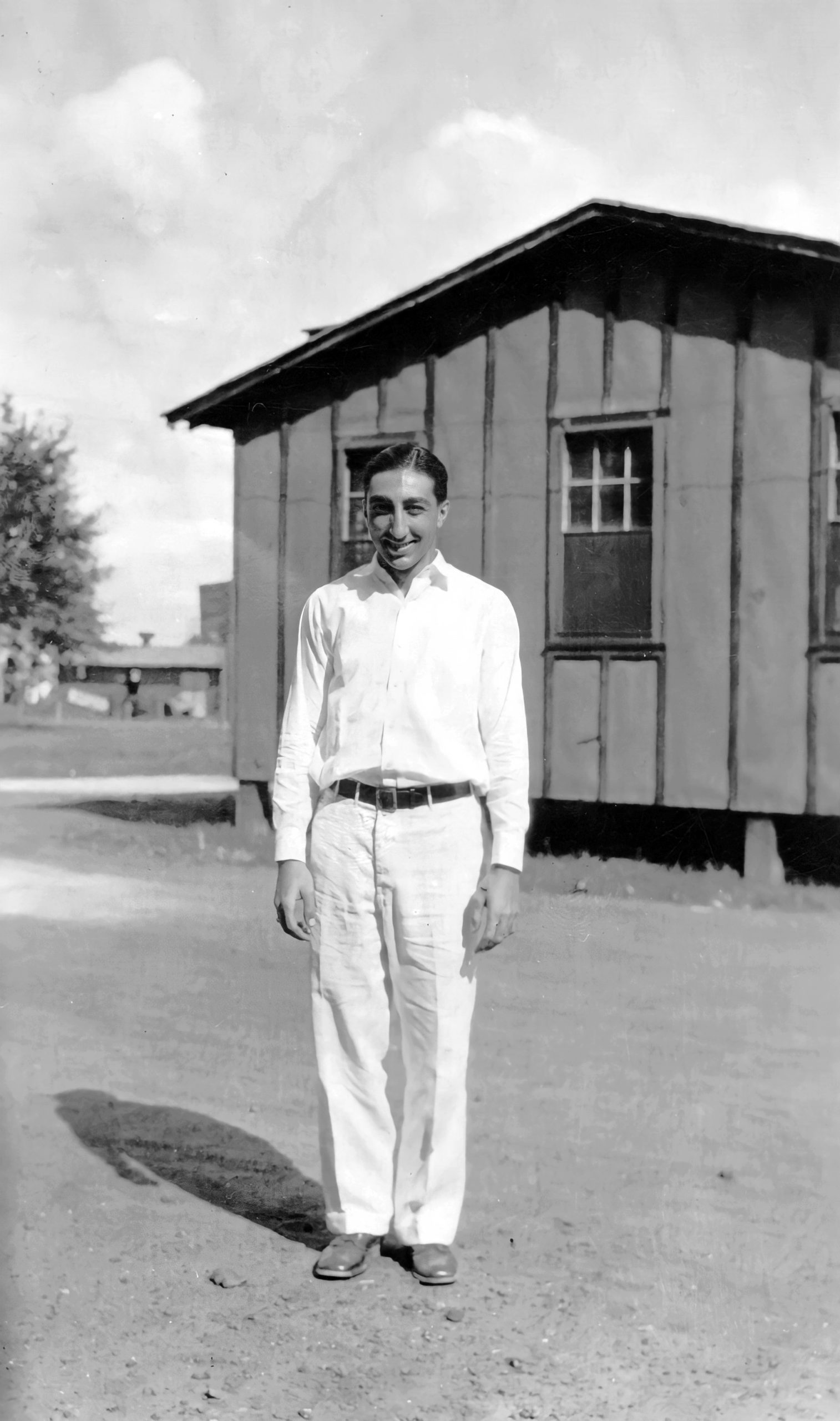

Michael DeBakey was born in Lake Charles, Louisiana, the oldest of the five children of Raheeja and Shaker DeBakey. Lebanese Christians, his parents had fled their homeland to escape the oppression visited on the Christian subjects of the Ottoman Empire. French speakers, they settled in Cajun country, where French was still spoken. The senior DeBakey was a pharmacist, and from an early age Michael DeBakey assisted his father in the family business. Conversation with the local physicians stirred his interest in medicine, and from an early age, he set his sights on a medical career. His parents insisted on a high level of academic performance, and he won admission to Tulane University in New Orleans. After completing his B.S. degree, DeBakey entered Tulane’s medical school, where he became a student of the distinguished surgeon and researcher Alton Ochsner.

Under Ochsner’s influence, he decided to become a surgeon and applied himself to the technical problems of surgery in the circulatory system, the heart and the lungs. While still in medical school, DeBakey invented the roller pump, which made it possible to provide a surgical patient with a continuous flow of blood. DeBakey’s invention would play a major role in the eventual development of open heart surgery.

DeBakey received his M.D. in 1932, and completed his internship and residency in surgery at New Orleans Charity Hospital. On Ochsner’s recommendation, he undertook surgical fellowships in Strasbourg, France and Heidelberg, Germany, mastering the latest surgical techniques from both Europe and America.

On his return to the United States in 1937, DeBakey joined the faculty at Tulane Medical School, where he continued his work with Dr. Ochsner. The two surgeons were among the first to notice a correlation between cigarette smoking and lung cancer. Although they were unable to demonstrate a direct causal relationship, they began reporting data which would eventually lead to a widespread acceptance of the dangers of smoking. During World War II, DeBakey was given military leave to serve as a member of the Surgical Consultants’ Division in the Office of the Surgeon General of the Army. He worked to station doctors closer to the combat zone, rather than in hospitals far behind the lines. In 1945, he was named Director of the Consultants Division, and was awarded the Legion of Merit for his contribution to the strategy of battlefield medicine. His concept was developed further during the Korean War at the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH). After returning briefly to Tulane following the war, in 1948 he joined the faculty of Baylor University College of Medicine in Houston, Texas. At Baylor, Dr. DeBakey became Chairman of the Department of Surgery, a post he would hold for the next 45 years.

While getting started at Baylor, Dr. DeBakey served on the Medical Advisory Committee of the Hoover Commission, appointed by President Harry Truman and chaired by former President Herbert Hoover to reorganize the executive branch. He helped transfer the Navy hospital in Houston to the Veterans Administration. With his guidance, the veterans’ hospital affiliated with Baylor, and became the home of Houston’s first surgical residency program. DeBakey hired a younger surgeon, Denton Cooley, to work with him at Baylor. For over a decade, the pair would work as a very successful team.

In the early 1950s, Dr. DeBakey’s prior invention of the roller pump became the basis of the new heart-lung machines that maintained the patient’s vital functions during surgery. With the aid of this device Dr. DeBakey was able to perform some of the first endarterectomies, removing blood clots and plaque material from inside the arteries.

In 1952, he performed the first successful operation on an aneurysm, removing the affected part of the artery and replacing it with a graft from a cadaver artery. The following year he performed the first successful endarterectomy on a carotid artery, a procedure that has spared countless patients from devastating strokes. Dr. DeBakey made another breakthrough in 1958, using a Dacron patch, rather than cadaver tissue, to repair an artery after performing an endarterectomy. The Dacron patch, now in use around the world, made it possible to repair aneurysms of the aorta that had previously been inoperable.

In 1963, Dr. DeBakey received the Lasker Award, the most prestigious honor in American medicine, but his greatest achievements still lay ahead. The following year, while attempting an endarterectomy that proved too difficult to complete, Dr. DeBakey tried a coronary bypass procedure that had only been performed successfully in dogs. In doing so, he became the first surgeon to perform a successful coronary bypass on a human patient. In 1966, Dr. DeBakey implanted a ventricular assist device (VAD) in a heart patient, removing the device after the patient‘s heart had recovered. He was the first surgeon to successfully use an implanted heart device, an important step to the development of the artificial heart.

Dr. DeBakey made a great contribution to medical education when he introduced the practice of filming surgical procedures with an overhead camera, enabling medical students and surgeons in training to witness rare or unusual procedures at close range.

Throughout the 1960s, Dr. DeBakey continued to serve as a consultant to the federal government. He was an early supporter of President Kennedy’s proposal to create the Medicare system of government-provided health insurance for the elderly. DeBakey’s stand put him at odds with the American Medical Association, but Medicare was eventually signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson in 1966.

Michael DeBakey was Chairman of the President’s Commission on Heart Disease, Cancer and Stroke (1964) during the administration of President Lyndon Johnson. Both President Johnson and his successor, President Richard Nixon, also turned to Dr. DeBakey for advice on their personal health issues. In 1969, President Nixon honored him with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. For reasons that remain unclear, President Nixon later placed DeBakey on his notorious “enemies list.”

In 1969, Dr. DeBakey led the separation of the Baylor medical school from its parent university, establishing Baylor College of Medicine as a separate institution. DeBakey served as President of Baylor College of Medicine from 1969 to 1979, and as Chancellor from 1979 to January 1996. The Department of Surgery at Baylor — along with numerous schools and other medical facilities — have been named in his honor. In the 1970s, Dr. DeBakey worked with Dr. Robert Jarvik in developing the artificial heart first successfully implanted in a human patient in 1982. In the 1990s, he worked with NASA engineers, adapting a miniature computer, which originally had been designed to monitor the flow of rocket fuel, to measure the flow of blood in a heart pump small enough for use in children.

Over the course of his career, Dr. DeBakey operated on over 60,000 patients, including former King Edward VIII of England and the deposed Shah of Iran. In 1996, he was summoned to Moscow to supervise quintuple-bypass surgery on Russian President Boris Yeltsin, enabling Yeltsin to complete his term of office.

At age 97, the doctor himself underwent open heart surgery — a so-called DeBakey procedure — to repair a tear in his aorta. The procedure was one he himself originated 50 years earlier. He was the oldest patient ever to undergo this operation. He recovered and enjoyed two more years of active life.

At the age of 99, Dr. DeBakey was still practicing medicine. In the last year of his life, he received the Congressional Gold Medal. He died two months short of his 100th birthday. Widowed and remarried, he was survived by his second wife and by a daughter and two of his four sons. The medical devices and surgical techniques he originated have extended the lives of countless men and women the world over.

No person did more to advance the surgical treatment of diseases of the heart and blood vessels than Dr. Michael DeBakey. As early as 1932, he developed components which became part of the first heart-lung machines. In 1936, he was one of the first to identify a connection between cigarette smoking and lung cancer. In the 1950s, DeBakey devised plastic tubing for repairing blood vessels, a treatment he applied to prevent recurring strokes, and kidney failure, and to restore circulation to limbs which might otherwise have been amputated. In 1963, DeBakey made history by installing an artificial pump to assist a patient’s damaged heart.

As Chairman of the Department of Surgery at Baylor University in Houston, Texas, he played a major role in the evolution of heart transplantation, artificial heart implantation and coronary bypass surgery. Countless men and women owe their lives to Dr. DeBakey’s work, and he was sometimes called upon to perform in the most conspicuous situations. When the life of Russian President Boris Yeltsin hung in the balance, Dr. DeBakey, already in his 80s, traveled to Russia to participate in the multiple-bypass operation that saved the ailing leader’s life.

Michael DeBakey received the Distinguished Service Award of the American Medical Association, and the René Leriche Award of the International Society of Surgery. Dr. DeBakey died on July 11, 2008 at the age of 99.

Dr. DeBakey, do you remember the first heart operation that you performed? What went through your mind when you were doing it for the first time?

Michael DeBakey: You’ve got to remember, we didn’t just suddenly start doing heart operations. We were doing other things around the heart. Finally, when the heart-lung machine came along, we were able to go into the heart. First, you learn what you’ve got to do in the experimental laboratory. We did literally hundreds of bypass operations on dogs before we did it on a human being. So it’s not a first operation in many ways.

Our first bypass operation actually developed as a kind of an accident. We had a patient, he wasn’t scheduled for a bypass operation. He was scheduled for what we call an endarterectomy, which we had been doing at that time, which was 1964. And because of the nature of the blockage, the plaque was such that we couldn’t separate it. We realized that we had to do something else, or else we couldn’t get him off the table. So we decided then and there to go ahead and do what we had been doing in dogs, which was about 50 percent successful. We just had to take that chance if we were going to try to save his life. Fortunately, it worked. It became the first successful coronary bypass.

Dr. DeBakey, how important is risk in your work? Sometimes you do have to take chances. How often do you have to proceed without absolute evidence?

Michael DeBakey: You do have to take some risks. For example, when I did the first operation for stroke, that was the first successful endarterectomy. This was in 1953. We had no experimental model to go by. Technically, we had already proven that you could do an endarterectomy; you could separate the plaque from the artery. So all we had was the evidence that had been built up previously, showing that these lesions were associated with strokes, and that patients who had died of strokes were all found to have these lesions. There was a good correlation. Therefore the suggestion from all of these studies was that if you could remove that, you might prevent someone having a stroke.

I had to take the risk on the first patient I did. He happened to be from Lake Charles, a bus driver who was having what we call TIA’s, transient ischemic attacks. And these attacks would occur in such a way that there wasn’t enough blood going to that part of the brain, and he would get partially paralyzed, temporarily, and have to stop, when he was driving a bus. He finally realized he couldn’t continue doing that. So his doctor sent him over here for us to look at. Not with that idea of doing this, but rather to see if there was anything we could do to help him. And I finally decided that this was the thing to do, and I talked with him about it, and explained to him it had never been done. But I explained to him what was involved, that the operation was a relatively simple technical procedure. And I think maybe because I was from Lake Charles too, he had confidence in what I said, and he submitted to it. Agreed. And it fortunately proved very successful. In fact, he lived 19 years after that, died of a heart attack. Never had any more transient ischemic attacks. So you do have to accept some risk sometimes.

I had the same experience with the first patient I operated on for an aneurysm of the thoracic aorta in the chest. This was a man from Arkansas, and he was having a lot of pain, because this thing was ballooning out, pressing on structures. So I explained to him that we had done this in the abdomen, but nobody had ever done it successfully in the chest. I thought the same principles would apply. And he finally submitted, I think mostly because he was in such severe pain. He wanted anything to get some relief. Fortunately it was successful. And so he became a pioneer in lending his efforts to getting this done. That started us on the whole course of getting aneurysms in the chest. As time went on, we developed techniques for all aneurysms of the aorta.

Dr. DeBakey, you’ve seen fit, from early in your career, to become involved in public debate of issues in the medical field. Medical research using animals is one of them.

Michael DeBakey: Yes. I have done so with the purpose of trying to direct the public’s attention to what I think is important for the public good, no matter what it is. Whether it was a recommendation to the President’s Commission on Heart Disease, Cancer and Stroke, for a regional medical program, or for regional medical libraries, or testifying before Congress about animal experimentation.

As far as animals are concerned, I don’t think the so-called animal activists have any greater concern for animals than we have. I have ten dogs in my house, and I don’t know how many birds. As pets. Even laboratory animals become the pets of the people in the laboratory. We certainly avoid any unnecessary harm or suffering to them. However I think it’s important to understand that, without doing animal research, you are going to stop doing certain types of research. Cardiovascular disease, for example. Everything that we do in cardiovascular work today is based upon animal research. Without them, we wouldn’t be able to do anything that we do today so well. Coronary bypass is a great example. But the replacement of arteries, and grafts, things of that sort, all came from animal research. So to stop animal research, you see, is, I think, a way of saying, “Well, I don’t care about any future advances in medicine. Let people suffer.” I can’t accept that kind of philosophy. I don’t think that’s humane either.

The Surgeon General’s report linking smoking to cancer didn’t appear until 1964, but you were reporting a link between smoking and lung cancer as early as 1939.

Michael DeBakey: At that time, we were involved in the study of cancer of the lungs. And on the basis of our studies, we became convinced that there was a linkage with tobacco smoking. We didn’t know exactly what it was, all we knew was that statistically there was a linkage. Even today we don’t know. We aren’t sure of the exact reason, but there is a great deal more work that has been done to confirm the fact that there is a very definite linkage between smoking and cancer of the lung.

You saw this issue more than 50 years ago. Did anybody listen?

Michael DeBakey: Not at that time. No. We were pooh-poohed. It was an epidemiological, statistical study, and many scientists don’t like to use that, don’t like to accept that. Especially if they are smoking, you know? And as you go back to that period, people were smoking a lot; a lot of people were smoking, even our people. And after World War II, even more, when all of the soldiers came back. You know, during the war they were getting Lucky Strikes and Camel cigarettes free. So a lot of them took it on because they saw the advertisements. So, there is no question that it’s bad for you. We know a lot more about it now. It’s bad for you in terms of not only cancer of the lungs, but other conditions like asthma, emphysema, and heart disease.

What took so long? Why was public awareness so slow in coming?

Michael DeBakey: Well, you’ve got to remember that there wasn’t a very strong movement; in other words, just a few of us sort of howling in the jungle, so to speak. And very few people paid any attention to it. And you’ve got to remember that the gap between smoking and the ultimate result may be 20 years, 30 years. See? So, at the moment, they don’t see anything harmful. That was much later. And that’s very difficult to appreciate by most people. People living today, they are not thinking about what’s going to happen to them tomorrow or next week.

More recently, you’ve addressed the issue of cholesterol and heart disease.

Michael DeBakey: There is no question that, again, you see, there is a linkage statistically between high cholesterol and heart disease. There is no question about that. If you took 100 people with high cholesterol, and 100 without high cholesterol, normal cholesterol, there would be more of the group with high cholesterol that would develop heart disease than those who didn’t have it. But at the same time, there is a substantial number of those who have normal cholesterol who are going to develop heart disease. So it’s not a guarantee against developing heart disease. It is a way of reducing the risk, but not completely guaranteeing against its occurrence. In fact, something on the order of a third of the patients with coronary bypass that we do have perfectly normal cholesterol.

Why is something like that so controversial?

Michael DeBakey: Well, that’s one reason why it’s controversial, you see. Because you can’t explain it, all of it, on the basis of cholesterol. But those who are working in the cholesterol field feel strongly about it, and they are recommending that everybody reduce their cholesterol level, you see. But there is no good, no good evidence that if you reduce your cholesterol level to below two hundred that you are going to be protected completely, and guaranteed against having a heart attack. So there is a certain amount of controversy, because the evidence is not absolute.