Sometimes in a defeat, you can set the stage for future victory.

Mike Krzyzewski (pronounced Sha-shef-ski) was born in Chicago and raised on the city’s Northwest side, among other working class Polish-American families. His father was an elevator operator, his mother a cleaning woman. The family shared a two-story home with relatives. From an early age, Mike showed enthusiasm for all sports, but by high school he was focusing on basketball. As a high school athlete, he made such an impression that he was recruited by Coach Bob Knight for the United States Military Academy at West Point, where he became captain of the basketball team. After graduation, he served in the U.S. Army from 1969 to 1974.

During his military service, he coached service teams and served for two years as head coach at the U.S. Military Academy Prep School at Belvoir, Virginia. After resigning from the service with the rank of Captain in 1974, Krzyzewski worked as a graduate assistant to his old Army coach, Bob Knight, at Indiana University. The following year, he returned to West Point as head coach. In 1980, he accepted an invitation to become head coach at Duke University, where he has remained. The first three seasons were disappointing, but over the next few years “Coach K,” as he is often called, led the Duke program through a remarkable turnaround. In 1984, Krzyzewski led his Blue Devils into the NCAA tournament for the first time.

Krzyzewski’s team reached the Final Four in 1986 and came within one game of winning the championship. In that year, they had played more games than any other team in the history of college basketball. With the departure of the five seniors on the squad, many observers expected a sharp decline in Duke’s basketball fortunes, but Krzyzewski’s 1987 Devils won 24 games and made it to the Sweet 16, losing to Indiana, which went on to win the national championship. From 1988 to 1992, he led his team to the Final Four for five consecutive seasons. UCLA’s legendary John Wooden is the only other coach in the history of the tournament to perform this feat.

In 1990, Duke again came within only one game of winning the national championship. Krzyzewski at last led Duke to its first national championship in 1991. In the banner year of 1992, Duke maintained the national number-one ranking throughout the season, and again won the national title, this time by 20 points. Mike Krzyzewski is the only coach since John Wooden to win two consecutive NCAA championships.

The Duke team made it to the championship game again in 1994, losing to Arkansas by only four points. After the tournament, Coach K underwent back surgery and was forced to take a ten-month break from coaching, but he returned to lead the Blue Devils into three more NCAA tournaments in 1996, ’97 and ’99. In 1992 The Sporting News named him Sportsman of the Year. He was the first college coach to have been so honored. He has also been named Coach of the Year by the National Association of Basketball Coaches (1991) and by Basketball Times (1997).

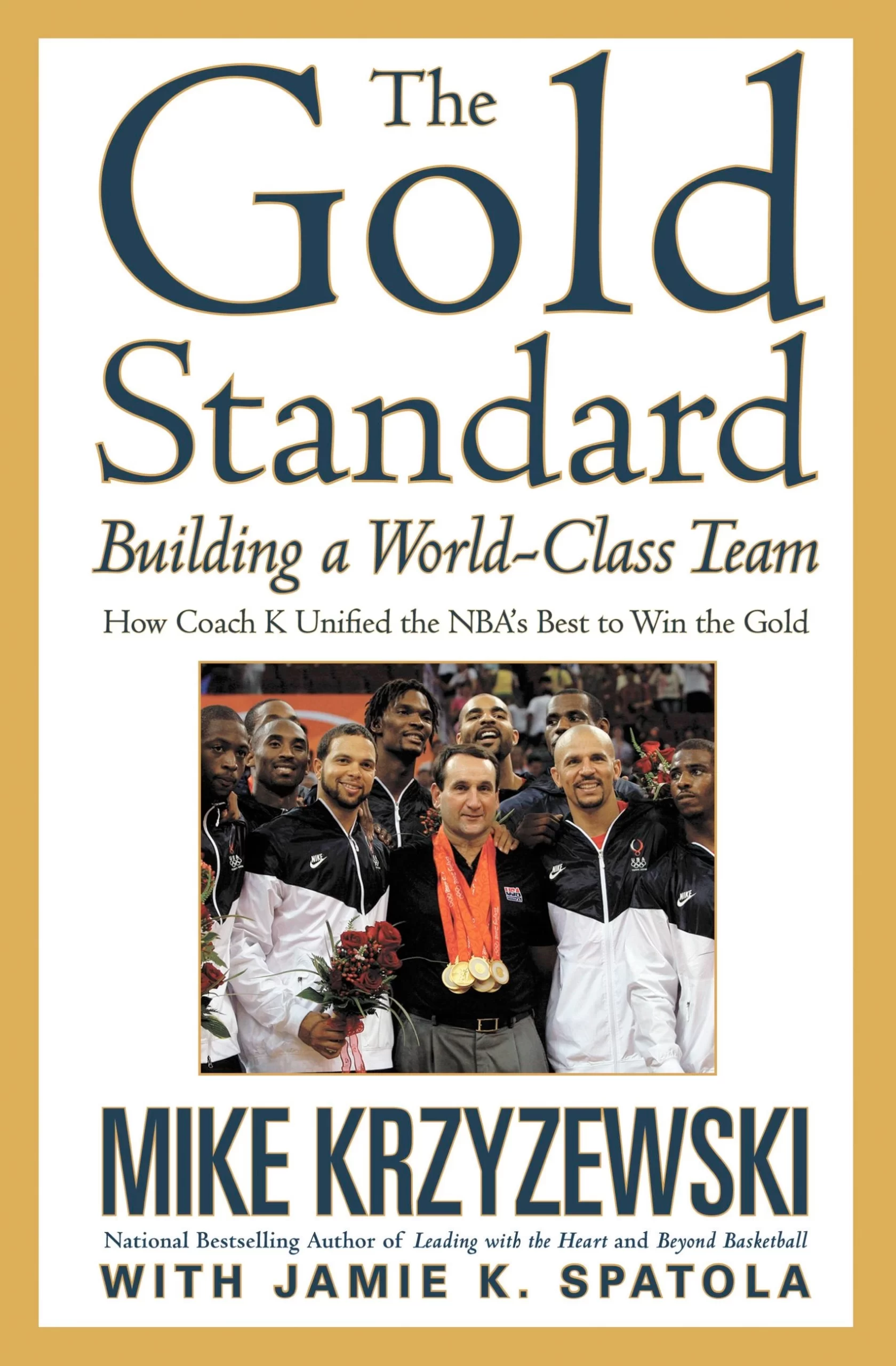

Coach Krzyzewski and many of his players are also active in international basketball. He served as head coach of the bronze-winning American team at the FIBA World Championships and won a silver medal at the Goodwill Games in Seattle. He assisted his old mentor Bob Knight at the 1984 Olympics and has served as chairman of the Player Selection Committee for all U.S. teams, including the 1991 Pan Am Team and the 1992 Olympic Team. As assistant coach to the legendary “Dream Team” he shared in the gold medal won by the U.S. at Barcelona. On October 26, 2005 Coach Krzyzewski was selected to be the head coach for the 2008 USA Olympic Senior National basketball team. With players like Carmelo Anthony, Kobe Bryant, LeBron James and Jason Kidd, Team USA claimed their spot in the 2008 Beijing Olympics and brought home the gold medal, a feat Krzyzewski-led teams would repeat in the 2012 and 2016 Olympics.

Mike Krzyzewski makes his home in Durham, North Carolina, where he and his wife, Mickie, have long been active in community campaigns against drug abuse and drunk driving. In past years, Coach and Mrs. Krzyzewski served as co-chairs of the Duke Children’s Miracle Network Telethon. Throughout his career, Coach K has seen himself as more than a coach to his players. During his tenure at Duke, of all the students who have played for him for four seasons, only two have failed to graduate on time. No other NCAA Division I college basketball team can make this claim.

To date, Krzyzewski has placed his team in more NCAA tournament Final Fours than any coaches other than UCLA’s Wooden and Dean Smith of North Carolina. He has won more Final Four games than anyone but UCLA’s Wooden, and has the highest winning percentage in the NCAA tournament of any currently active coach. Duke’s victory over Arizona in the 2001 tournament gave Krzyzewski his third NCAA championship, tying him with his old coach and lifelong mentor, Bob Knight.

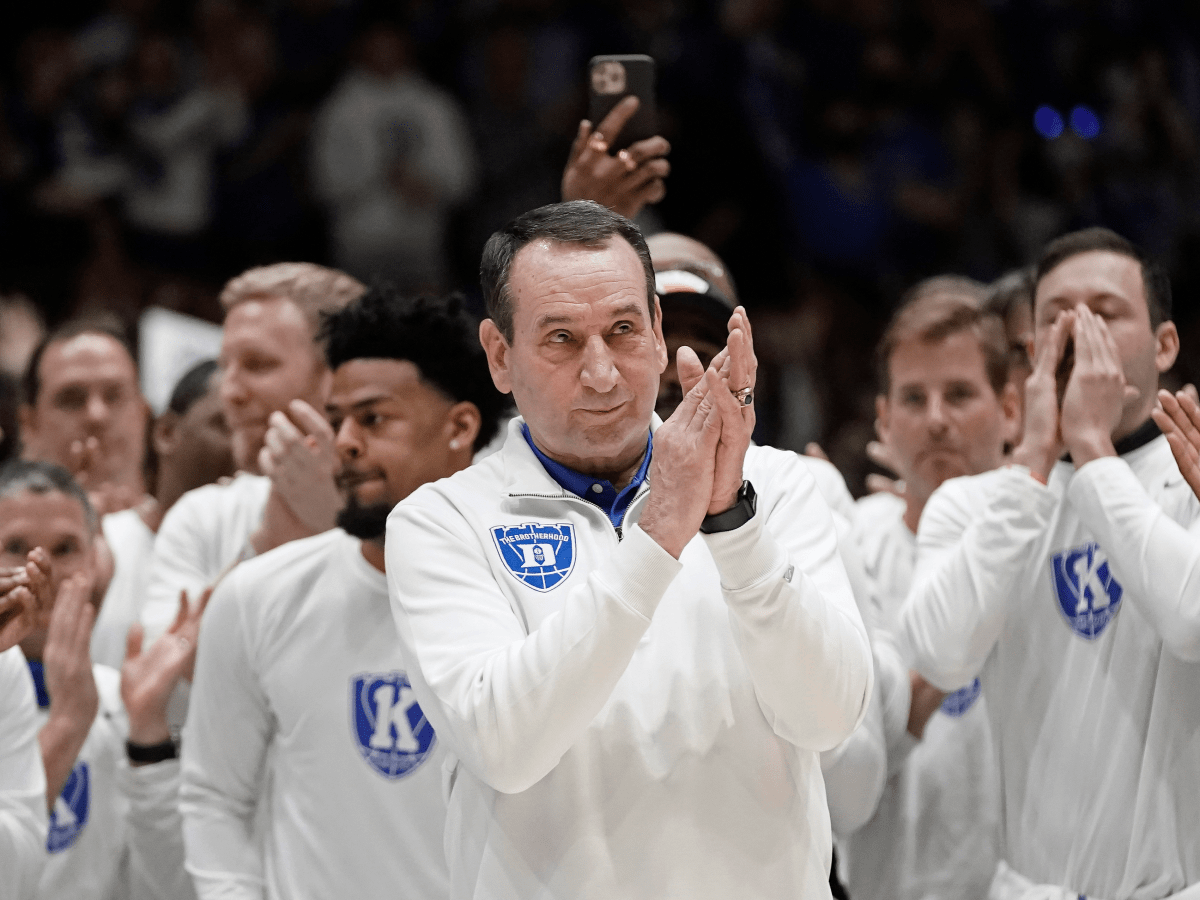

A cliffhanging 61-59 victory over Butler in the 2010 tournament gave him a long-sought fourth championship, surpassing Knight’s record and equaling that of Kentucky’s Adolph Rupp. Coach K broke another record in 2011, when Duke beat Michigan State 74-69 in the State Farm Champions Classic, giving Krzyzewski his 903rd win. This victory broke another tie with Knight and made Mike Krzyzewski the winningest coach in the history of NCAA Division 1 basketball. Duke’s victory over St. John’s at Madison Square Garden on January 25, 2015 was his 1,000th victory, a record never before attained by any coach in the division. Duke ended the 2015 tournament defeating Wisconsin 68-63, giving Coach K his fifth national title.

The following year, Krzyzewski coached the U.S. men’s basketball team to a gold medal at the Olympics in Rio de Janeiro. A 99-96 victory over Serbia captured a third consecutive Olympic gold medal for the U.S. men’s team and Mike Krzyzewski. After 41 seasons as head coach at Duke, Mike Krzyzewski announced his plans to retire following the 2021-22 season.

Over the years, Krzyzewski turned down spectacularly lucrative offers to coach professional teams, including the Los Angeles Lakers. His continuing commitment to the college game — and his loyalty to the Duke University community — made him an exemplary figure in the world of sports.

On March 5, 2022, Krzyzewski coached his final home game with the Duke Blue Devils. The North Carolina Tar Heels upset the Blue Devils, 94-81. Krzyzewski leaves Cameron Indoor Stadium after 42 seasons as the winningest coach in college men’s basketball with 1,196 wins and five national championships to Duke. On April 3, 2022, at the Caesars Superdome in New Orleans, forty-two years and 1,202 victories later, Krzyzewski’s career ended with a loss to UNC. It was his 13th trip to the Final Four. “I’ve been blessed to be in the arena,” Krzyzewski said. “And when you’re in the arena, you’re either going to come out feeling great or you’re going to feel agony. But you always will feel great about being in the arena. And I’m sure that’s the thing when I’ll look back that I’ll miss. … But damn, I was in the arena for a long time. And these kids made my last time in the arena an amazing one.”

“When I was growing up, there weren’t any Little Leagues in the city. Parents worked all the time. They didn’t have time to take their kids out to play baseball and football. We understood that as kids, so when we congregated at a school yard, if you had six people, or ten or 20, somebody had to organize it, and it was always me.”

Growing up in a working-class neighborhood in Chicago, Mike Krzyzewski learned to rely on himself to organize the games he wanted to play. When he failed to make his high school football team, he turned to basketball and became a local star. At that time, he hoped for nothing more than to teach high school and coach basketball. A recruiter from the U.S. Military Academy changed all that. At West Point and in the United States Army, Krzyzewski began playing and coaching at a higher level than he had thought possible.

In time, he became the winningest coach in the NCAA. As head coach of Duke University’s Blue Devils, he placed his team in five consecutive Final Fours and won five national championships. In 2015, he became the first coach in the history of NCAA Division 1 men’s basketball to win 1,000 games.

While his teams boasted such star players as Grant Hill, Christian Laettner and Shane Battier, the sustained success of the Duke program must be credited to Coach Krzyzewski’s long-term strategy. While other schools may be willing to sacrifice their academic criteria for the sake of a winning team, “Coach K” held his players to the highest standards on and off the court. In so doing, he won the accolades of his peers and the affection of the entire Duke community.

It must be hard to single out particular moments, but are there one or two in your career that stand out as the most exciting or thrilling?

Mike Krzyzewski: There are a lot, but two of them will do. After we beat Nevada Las Vegas, in the semi-finals in the 1991 Final Four, they’d won 45 in a row. The Duke world — and in some respects the basketball world — went crazy. We still had to win one more game. We had to beat a really good Kansas team to win the National title. It’s so difficult to aim high again, after you’ve achieved something great, especially right away. Here, 48 hours later, we had to win again, and we did. I love that. I love that we were able to do that. The second time…

I was involved in probably one of the great games in the history of college sport, when we beat Kentucky in ’92 for the Eastern Regional Championship. Rick Pitino and his team played great, and so did we. We were down by one, with 2.1 seconds to go in overtime, and the world seemed like it was over. At that point we, as a group, connected again, and we said, “We’re going to win.” We talked through how we were going to win, and then we did. Everyone said we were lucky, but my feeling is that luck favors people who trust one another. Those two moments are, for me, great moments. Actually, the Kentucky moment was better than winning the two National Championships, because it was the epitome of what I try to get from a team in a crisis situation.

The way you describe it, it sounds like it could have taken half an hour, but it must have been very fast. What you’ve just described, when you said, “We’re going to win.” How long did that take?

Mike Krzyzewski: TV time-outs take longer than normal time-outs but, a couple minutes. Our bench was on one end of the court, and Kentucky had just scored at the other end of the court. They scored, and our team called a time-out with 2.1 seconds. You could see our team coming to the bench.

I had a towel in my hand, and I threw it to the floor. I was angry, not because we were losing, but the shot that put us behind was a bank shot, from straight on, and you don’t do that. People don’t shoot bank shots. To me, it was a lucky shot, and I didn’t want to lose that way. So I used my anger properly.

I met my team, and I told them, “We’re going to win,” and I looked into their eyes. Then, when they sat on the bench, I looked at them again, I said, “We are going to win.” I felt we were connected. Then I asked Grant Hill — instead of telling him what to do — I asked Grant, “Can you throw the ball 75 feet?” And he said, “Yes, I’ll throw it.” And by saying it already, I think he had already done it. In fact, I think if you had interviewed him now, he would say that, “Well, I gave my word that I was going to do it.” But if I said, “Grant, you throw it,” it would have been me telling him to do something. I asked Christian Laettner, “If they ring you up, can you catch it?” He says, “Coach, if Grant throws it, I’ll catch it.” All of a sudden, there was that — some people would call that bravado, or cocky talk, but we had gone from walking off the court scattered, mentally and physically, to now, a minute and a half later, to believing that we were going to win. Everybody interacted in that. Laettner’s remark set a very positive tone. It was like, “Yeah, come on, we’ll do it.” Grant threw it, and Christian caught it, and he shot it, and he hit it, and we won. It was truly a unique time.

In that time of just utter happiness for us, right in front of me, there was a kid named Richie Farmer from Kentucky. I didn’t even see the shot go in, because everyone jumped up, but I knew when he shot it that it was going to go in. Our kids were jumping, and I looked at Richie Farmer, and he was like this: “That could have been us.” So my initial thing was to go out to him, and not to our team, just because it seemed a little bit unfair, that you could be in a great game like that, and there was this extreme here, and this extreme down here. As a teacher, I didn’t like that, but that’s the way it is. That’s where great moments come about. But I’ll always remember my feeling about Richie, when that happened.

The picture of failure?

Mike Krzyzewski: Right, but it wasn’t failure, really. The world would say it was failure. But the difference was so small between us. They played great, but they lost. What I try to get across to our guys, and I hope I did it with Richie Farmer in a brief instant, is to say, “You didn’t fail.” Sometimes when you say that after you win, people say, “You can say that, because you just won.” But I truly felt that. To have empathy for someone who has lost, I think, gives you greater appreciation for what you’ve won. I think it gives you better perspective than by looking at it as, “We’re hot stuff now. We’ve won.”

So it’s about ethics too, and empathy.

Mike Krzyzewski: Ethics and empathy. I hope we never lose that in collegiate sport. Professional sport is different. It has an entertainment aspect and, I wouldn’t say winning at all cost, but it has a clearer definition of winning. Collegiate, amateur sport does not have that, where only the winner is a winner. There are a lot of winners. I hope I never lose that in amateur sport. We are losing it a little bit, and I worry about that.

Tell us about the first National title, how that felt. Did you feel, going into that season, that you had the championship team?

Mike Krzyzewski: For a college basketball player or coach, to reach the Final Four is la-la land. You’ve achieved, you’ve got your stamp of approval. My first team to do that was in 1986. Then we did it in ’88, ’89 and ’90. But we did not win the National Championship. I feel that, because we were achieving at a high level, I rationalized somewhat, at a moment when maybe I could have pushed my team a little bit more.

In ’91, we were playing Nevada Las Vegas, and they’d won 45 in a row. It was almost like it would be okay to lose. Everybody would say, “Oh, that’s all right.” That, to me, was the biggest obstacle. I was most proud of that game, because, as a leader, I helped my group overcome rationalization at the highest level. When we beat them, and then beat Kansas for the National Championship, everyone was saying, “Boy, you won the National Championship,” but for me, it was amazing because I got over that final hurdle, as a leader and a teacher. Now I know how to do that, and I thought it helped me the next year when we won it a second time.

You had suddenly reached this exalted level, but how do you push on from there? Is that similar?

Mike Krzyzewski: Yes. It’s the challenge of continuing success. What floor are you on as far as your success ladder?

Once you win a National Championship, how do you do that again? How do you get the passion to do that again? We won it again right away, the next year. A lot of it had to do with the fact that I didn’t give myself an opportunity to enjoy the first one. I went right away into the second one. I didn’t want any “computer viruses” getting into my mind. I even played a game, a mind game, a word game with myself. After you win the next year, people will say you’re “defending” your National Championship. I prohibited the use of the word “defend.” What I said, for that team, I said, “We’ve already got the National Championship for that year. We’re going to pursue.” And sometimes the difference between defend (protective) and pursue (go after), I think, was the difference in us winning it the second time.

Now you might ask, why didn’t we win it the third time? I probably didn’t do as good a job of coming up with those words, or someone else did a better job of coming up with their words and talent than I did. It’s interesting, what the human mind can do.

How do you help the kids get over that kind of defeat? When they’re so close, it must be devastating.

Mike Krzyzewski: Each group and each youngster is different. As a leader or coach, you get to know what they need.

In 1989, I remember, we lost in Seattle to Seton Hall. After the ball game, we came back to my suite where we meet. It was the last time our group of people were going to be together. That’s the last game. But there were other kids who were coming back. I said, “Instead of going home, we’re going to stay through the National Championship game, because we’re eventually going to win a National Championship.” Sometimes in a defeat, you can set the stage for future victory. I wanted them to feel good about what they had accomplished. Not to like losing, but to like the success that they had. And then to go on, maybe, to put them in a position where they might be able to. I try to do that, and now I’m teaching it in game situations. In November, I might do a thing where it’s an end-of-game situation: “Well, this is what we’re going to do, fellas, in the Final Four.” Little things like that throughout the year create a championship mindset.

I have a rule on my team: when we talk to one another, we look each other right in the eye, because I think it’s tough to lie to somebody. You give respect to somebody. “It’s you that I’m talking to right now.” As a result, I know that there are going to be times on that bench where there’s two seconds to go, or where a kid’s having a bad game, and I’ve got to say, “Look, you’re playing horribly, but you’re not horrible. So get your head going,” or whatever words I might use. “I believe in you.” I might not even say it that way. It might be two seconds, and we have to connect. If we haven’t done the work beforehand, you can’t wait ’til those two seconds to do it. I speak to a lot of groups, and with business groups, a lot of them ask about crisis management. “What do you do with crisis management?” Well, the main thing that you do with crisis management is trust one another. Well how do you get that? Wow, it takes a while. But being honest with one another is the very first and most important step. That’s where teamwork comes in. If you have talent with teamwork, you’ve got a chance to be a championship-level team.