When did you first have some sense of what you wanted to do in your life, as a career?

Murray Gell-Mann: Well, I had a very strong sense when I was a little child. But I didn’t go ahead and do that. I wanted to be an archeologist, and perhaps a linguist. And I had absolutely no inclination to working on physics, none whatsoever.

So how did you get from wanting to be an archeologist or a linguist to being a famous physicist?

Murray Gell-Mann: Well, let’s see if we can trace it. I was in my senior year in high school, and I was applying for admission to Yale for the following year. And one of the questions on the application form was, if you were admitted to Yale, what will be your major subject. And I thought I would discuss that with my father. Not for any particular reason, it didn’t really matter what I filled in. Because when I got to Yale, if I was accepted, I could have changed it to anything else, it really didn’t matter at all. But it seemed the thing to do. My father and I didn’t discuss many things, but it seemed like something that would be useful to discuss with him. So I mentioned it. And he said, well, what are you thinking of putting down. I said archeology, linguistics. So, he said, “You’ll starve.” He was very much impressed with the effects of the Depression, which had, among other things, completely changed his position in life. And he felt that I should have some reliable source of income, some skill that would allow me to make a living even in difficult economic circumstances. I said, “Well, what would you like me to study?” and he said “Engineering.” I replied that I’d rather starve. And besides, if I built anything it would fall down. I really don’t have any talent for engineering. So then he said “Well, why don’t we compromise on physics.” And I thought he must be joking. I took a course called physics in high school, and it was the only course in which I did badly. It was a really terrible, terrible class. We studied the seven kinds of simple machine, we memorized the names of the seven kinds of simple machine. We learned the three forms of Ohms Law, E=IR, I=E/R, R=E/I. And we studied about mechanics and wave motion, and electricity and magnetism, and acoustics, and so on and so forth, without ever seeing any connection among all those subjects. And surely he wouldn’t want me to go on studying that. My father said if you keep studying physics, study advanced physics, it will be very different. You will learn about relativity, and quantum mechanics, and it will be really exciting. And so, at that point I decided not to pursue the conversation. I wrote down physics, knowing that it didn’t make the slightest difference. When I got to Yale I could change it, if I ever got there.

Well, I was indeed admitted to Yale, with a very generous scholarship, and the next year I went there. And, but I was too lazy to switch from physics to some other major. [laughs] So I continued doing physics. Eventually it was true that quantum mechanics and relativity were really exciting, and I enjoyed it, and I kept on doing theoretical physics.

So, but for laziness, you might have been an archeologist?

Murray Gell-Mann: Yes!

We’ve heard that your father was an avid reader. Did he pass that on to you? You moved very quickly through school.

Murray Gell-Mann: Yes, my father read a good deal. But what he did most, when I knew him, was to study math and physics and astronomy as an amateur, and try to learn about them. I don’t know exactly how far he got. I am certain in very special kinds of mathematics, not terribly advanced, but rather specialized, he made a lot of progress. And in other things, I really don’t know. I know he spent a huge amount of time poring over math and astronomy.

You obviously saw in him a great curiosity for the way the world works.

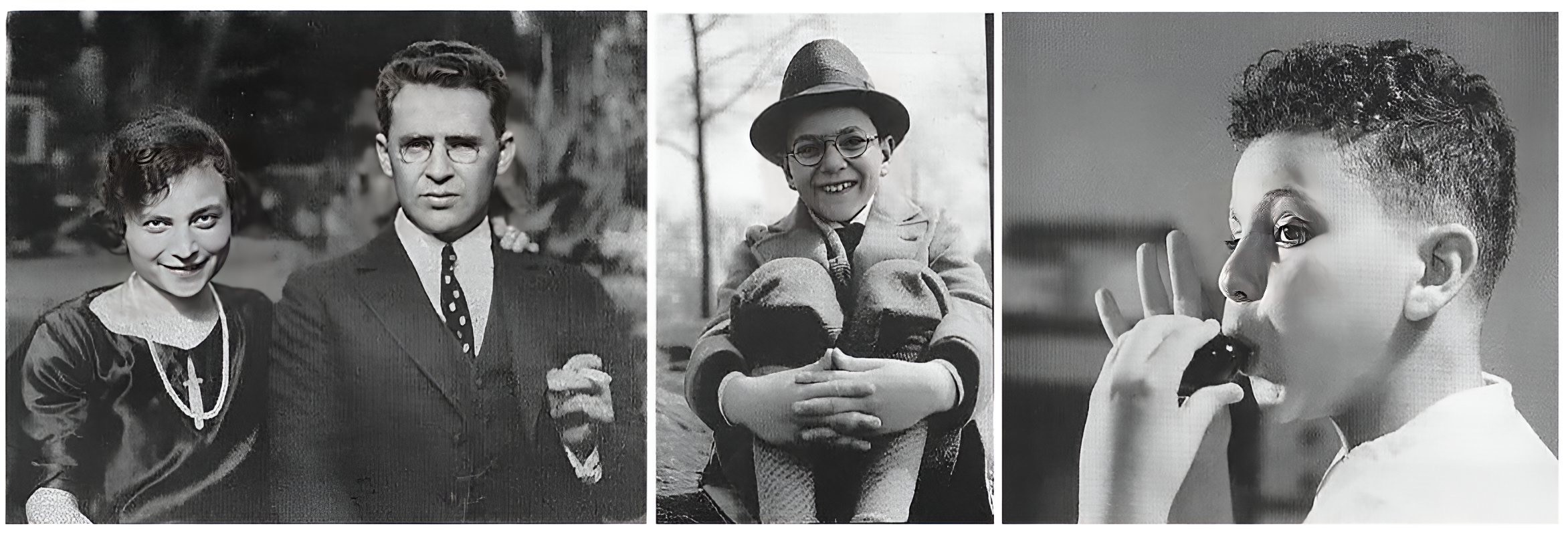

Murray Gell-Mann: Yes, to some extent. But it was mainly my older brother from whom I learned things. He in turn, had learned a lot from my father, but in my case it was mostly my older brother Ben — who was nine years older — who introduced me to the wonders of the world.

For example?

Murray Gell-Mann: Oh, lots of examples. We loved nature, and we spent a lot of time outdoors, learning about birds and trees and flowers and mammals, and so on. It was really great. Natural history was a passion, which I think I acquired from my brother. We thought of New York City as a hemlock forest, that had been too heavily logged, and we spent a lot time in a little fragment of hemlock forest that was still standing. Particularly birds. My brother was passionately interested in birds, and I became so also. I still am.

Didn’t you go out and try to count as many birds as you could find?

Murray Gell-Mann: Well, people do that, bird watchers do that, generally in the spring. Most bird watchers have done that many times. Actually I have done it more recently, a couple of years ago with my brother ,where he lives now. In between, though, the 50 years or whatever in between I didn’t do it. But yes, we went out on a big day in the spring in New York about 50 years ago. It’s become a sort of competition now among heavy hitter bird-watchers all over the world, to try to see as many species as possible. Of course, your location matters enormously. The record is held, I think, by the Manu National Park in Peru, but I know people in Africa have done very well, and people in Texas do well, and so on. This area isn’t bad, Southern California, to see a great variety of birds.

What kinds of things did you read, as a child?

Murray Gell-Mann: Through my brother I became interested in a great many different things. I just attended his 70th birthday party a little while ago. Two weeks ago, in fact, in southern Illinois. And I told about all the things I had learned, many of the things I had learned from him. He taught me to read, for one thing, at a cousin’s house, from a Sunshine Cracker box. And then, well, we were interested together in all sorts of things. Archeology and history, and art to some extent. We would go to art museums. We went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York sometimes. He would sketch the ancient Greek statues, and I would go look at the Egyptian antiquities, and things of that kind. I talked about nature, about birds and butterflies, and plants. We talked about a great many other things — languages. Just about everything. And what was nice was that we didn’t distinguish sharply among them, with artificial boundaries. Now we’re talking about art, and now we’re talking about science, now we are talking about social science, and so on. It was just all the richness and beauty and order in the world.

Did you read much fiction in those days, or were you mainly interested in nonfiction?

Murray Gell-Mann: I read some fiction. Yes.

What were your favorites?

Murray Gell-Mann: When I was a boy? Very hard to remember. H. G. Wells, certainly was a favorite. Scientific romances and so forth, but also the novels.

Did you have a favorite?

Murray Gell-Mann: That’s very hard to remember. Various mystery stories, adventure stories, and so on. I liked short stories. I’ve always liked short stories. So I devoured the Sherlock Holmes stories by (Sir Arthur) Conan Doyle. The Father Brown stories by Chesterton — even though I didn’t like Chesterton’s attitude toward the world I enjoyed the stories. The Saki stories — H.H. Munro short stories. I guess my favorite reading was a really thick book of all the short stories of some prolific author.

The wonderful thing about the Sherlock Holmes books was that logic always prevailed. No problem was unsolvable. Whatever mystery presented itself could be resolved eventually if you just applied your mind to it.

Murray Gell-Mann: Yes, the power of theory. Most people don’t appreciate the power of theory. I like to give illustrations which are from relatively ordinary things. For example, here along the California coast, we have a lot of places with Spanish names, named by Spanish explorers. And people who live here know that. But it never occurs to them that there is a theory of the name. At least it doesn’t occur to most of them that there is a theory of the name. But in fact, they are related to one another by a set of laws., because they were almost all named after the day on which the sailing voyage reached them. So if you have a Catholic Calendar, and a map, you can trace the sequences of names along the California coast according to the Saint’s days and so forth that were the days of discovery. You can see that on three voyages or so, virtually all the names were given in sequence. Of course, one of those names is Punta Año Nuevo, Point New Year’s Day, which was discovered on New Years Day. But the other nearby points and towns were also named after days in December and January preceding and following New Year’s day.

Is it that kind of curiosity that propels people into science? To look at things and wonder, “How did it get this way? Why is it like that?”

Murray Gell-Mann: To see pattern and regularity, and then to try to understand the pattern and regularity. You can think of it as two separate things. One is to see that there is a pattern, and the other is to understand how the pattern might have gotten that way. Sometimes it is divisible into those two parts. Not always. Sometimes they go together.

You’ve said that your brother encouraged your curiosity about the world. What about your parents? How much direction did they give you?

Murray Gell-Mann: Well, my mother didn’t have much to do with that sort of thing. My father was probably happy that I was learning things, but he wasn’t the sort of person to give a lot of encouragement. He actively discouraged the natural history expeditions. He didn’t like that sort of thing. I never figured out exactly why. I think maybe it was because he grew up in the back woods. His father was a forester in an extremely remote area of what was then the Austrian Empire. I think he was so glad to get into a city, he never wanted to leave, and didn’t like the idea of my poking around in the woods and the swamps. Also, in my brother’s case it distracted him from school. He was a college drop out at the age of 15 because he was so passionately interest in the woods, particularly birds. So that may also have played a role. But I think the hostility may have come earlier than that.

Your brother dropped out of college at age 15? That means he started before age 15.

Murray Gell-Mann: Yes.

You also began college at age 15.

Murray Gell-Mann: But I didn’t drop out.

You stuck with it. How do you account for the fact that both you and your brother began college two or three years before most of your peers?

Murray Gell-Mann: Well, it’s a matter of fashion, whether the schools like to promote people rapidly — if they show a capacity for being promoted rapidly — or not. Sometimes the prevailing educational philosophy is that you have to leave people with their age group, and sometimes it is that you don’t, that you promote them. But at that time, skipping, as it was called, was popular. Shortly, the schools mostly stopped doing that.

Did they think it was bad for the student?

Murray Gell-Mann: For whatever reason. One system is to leave kids in the class with the kids their own age but give them a lot of advanced material to work on. But then it matters whether they have to do their regular dull class work as well. If they’re excused from the usual stuff, and sit in the back of the room doing calculus, I think that’s better than having to do the usual junk, plus material for enrichment. The other, I think, is terrible. Doing all this stuff that they learned years before and that they know perfectly — and it is true drudgery — plus material for so-called “enrichment.” I think that is an extremely poor plan.

Were you bored at all in school, or did they allow you to move fast?

Murray Gell-Mann: I skipped enough so that I wasn’t completely bored. I usually learned the stuff right away, or at least often. I shouldn’t say usually. In many classes I learned a lot of the things in the beginning, but there were others where it continued to be interesting all through the year, history class for example. We happened to have a very high quality history teacher in grade school. It was shortly after that he became chairman of the history department at Barnard, but at that time, during the Depression, he was teaching grade school. I didn’t at the time like him particularly, but he was certainly a very good teacher. Later on I liked him, and just at the end of his life we got to know each other.

What kind of conversations did you have with him at the end of his life?

Murray Gell-Mann: Oh, we talked about lots of things that we had done in between. He was writing a history of President Franklin Roosevelt’s dealings in foreign affairs, particularly in connection with Indochina. He was astonished that I knew some things about that. So we talked about it and it was very interesting. He wrote a lot of books, he did a lot of scholarly work. He was a rather well-known historian.

You moved through school so quickly, you obviously were very bright and picked up things much more quickly than some of your classmates. How did you get along with other students when you were in school?

Murray Gell-Mann: Oh, it varied a lot. It got better and better as time went on. High school wasn’t bad at all. Grammar school wasn’t so great. It got better in high school. Going to college, similarly, it was not perfect in the beginning, but later on it was very good. I made a lot of wonderful friends, many of whom I still know and see.

What was the problem in grammar school?

Murray Gell-Mann: Well, when I would just arrive, the others knew one another, and I was much younger, and much smaller, and couldn’t play the games so well. So I wasn’t very popular, but over the years it got better.

Was that because popularity gets defined in different kinds of terms?

Murray Gell-Mann: Well, among kids it gets defined in sort of ridiculous terms, which have almost nothing to do with success in later life. It’s really sort of funny.

You often see stories where the person who was the most popular in high school is among the least successful later in life.

Murray Gell-Mann: That’s right, often true. So all of that hierarchy in school is sort of absurd in many cases.

You mentioned a number of writers who interested you as a boy. What about H.G. Wells? A number of our interviewees have mentioned him.

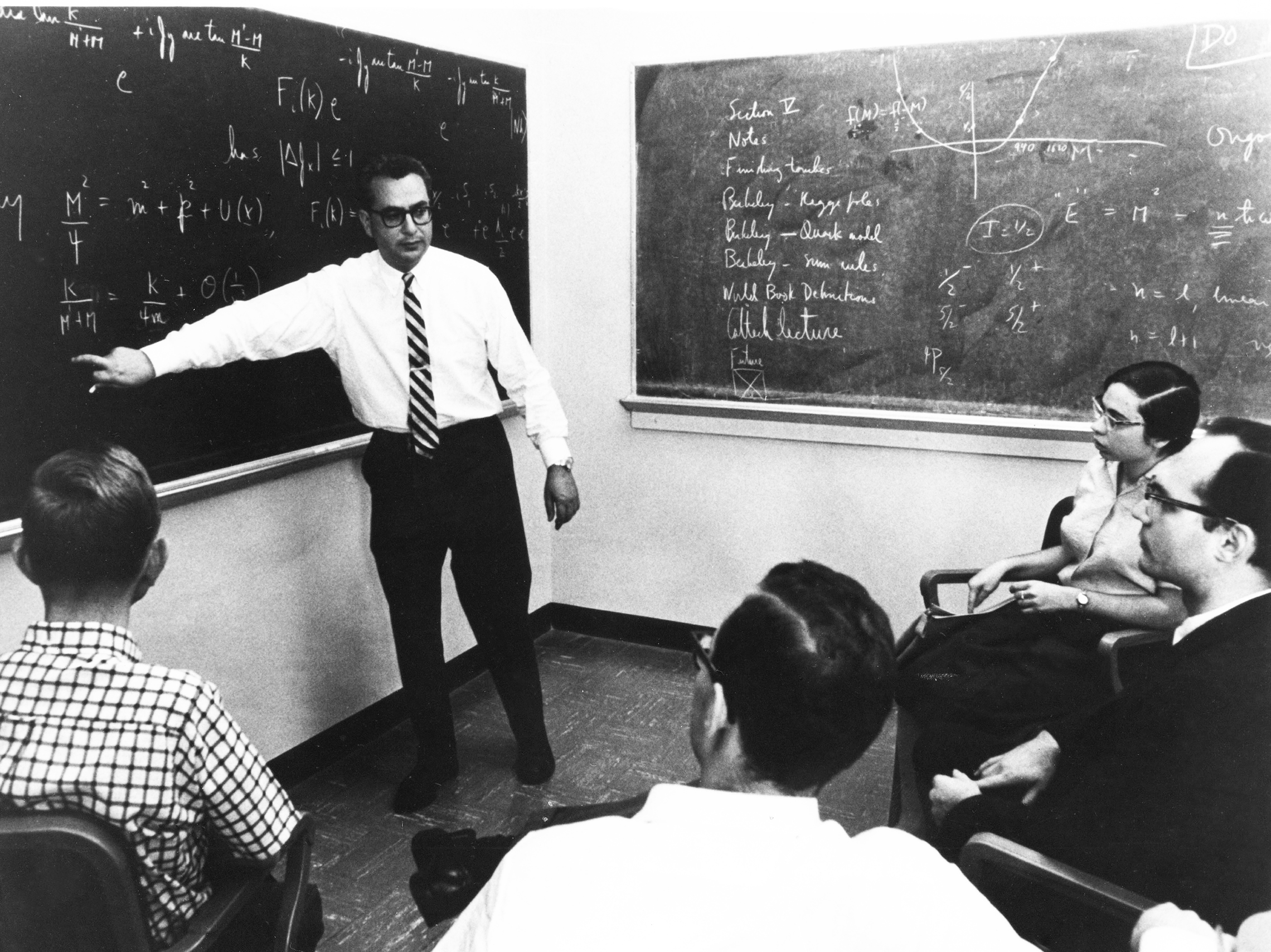

Murray Gell-Mann: Well, he and many lesser writers of so called science fiction dealt with the future, and that was interesting, because the future is fascinating. And in most serious literature, one didn’t see much discussion of it. You remember the Ibsen play (Hedda Gabler) where there are two historians, the woman’s husband, who was a rather conventional historian, and her lover, who was a more daring one. The daring historian’s book goes right on into the future. The other historian says, “But what can we know of the future?” and the writer says, “Well, there is thing or two to be said about it. We don’t know about it but there is a thing or two to be said about it just the same.” So, many scientists have gotten into science through science fiction, I think that’s true. Another thing is that — not particularly true about H. G. Wells, but it was true about some of the science fiction magazines — that they discussed active questions in science, where the books you could get in the library and so on were mostly very far out of date, and did not discuss active questions. Even in college, I found that I couldn’t get anybody to talk with me about contemporary questions.

Really? Why?

Murray Gell-Mann: It was a difficult time. It was during the war, and most of the best people were away. But even after the war ,when they came back, it was still very difficult to get people to discuss active research questions. There’s this idea that students aren’t good enough to know about what is going on in science. They should be told some old stuff. But as time goes on, items in the curriculum will move down to a more elementary class, as it gets easier to talk about. But the new ideas are usually put out of reach of the students.

So students get told the old stuff, sort of an intellectual version of hand-me-downs?

Murray Gell-Mann: Something like that, yes. Exactly. It’s a funny custom which I don’t particularly approve of. I don’t know why they can’t be told about the latest stuff. I don’t see that it does any harm to tell them about it. You may not be able to tell it to them in its full glory, but you could tell them a lot about what is going on. I don’t know why that’s so bad.

Do you think there is the notion that they haven’t spent enough time? That they haven’t paid their dues enough?

Murray Gell-Mann: Perhaps. I don’t know. It’s very hard to plumb the depths of people’s motivation. But possibly something like that. Certainly, as notation improves, it gets easier to teach things to more elementary students. I’m sure, in Roman times, that multiplication with roman numerals was a graduate subject. As people learned better notations, it became easier to teach multiplication. They were able to move it down in the curriculum.

You mentioned your interest in archeology, and being a linguist, and so forth. Was there anything else that you wanted to be, that you didn’t get to?

Murray Gell-Mann: Explorer. But, I’ve done little bits of those things recently, and that’s rather fun. But I never really became an archeologist, or a linguist or an explorer.

You said that when you first began studying physics, you found some things that were a little more inspiring than the basic textbook physic.

Murray Gell-Mann: Well, specifically, quantum mechanics and relativity. What my father had said would be interesting, turned out actually to be interesting. So on that he was right.

What was it that interested you about relativity and quantum mechanics?

Murray Gell-Mann: They are just some of the greatest achievements of the human mind. Relativity, quantum mechanics, they are spectacularly interesting things. And of course they opened up the question of how general relativity and quantum mechanics would be combined together in a successful theory. For that, we have now, here at Caltech, and elsewhere, the first candidate theory in history for a unified quantum field theory of all the particles and all their interactions which does actually reconcile quantum mechanics to general relativity. Whether it’s right or not, we don’t yet know, but it is spectacularly exciting, and for the first time in history it is a candidate theory that seems to have the right properties to be the right overall theory of all the particles and all their interactions. Developed by my friend John Schwartz and his colleagues, in great part right here on this floor.

Are we now at a point in science where we are on the verge of being able to explain how everything in the world works, and how it all relates?

Murray Gell-Mann: Very close in some ways, I think. First of all, there are the fundamental laws of physics. One of which is the unified quantum field theory of all the particles and all the interactions that I was talking about a moment ago. In the Superstring Theory of John Schwartz and his colleagues, we have the first really good looking candidate for that, and he may be right. But even if it’s wrong, I believe that it will turn out to be an important step on the way to the right one. But, what is quite possible is that it’s actually right. The other part of the fundamental law of physics is the boundary condition near the beginning of the expansion of the universe. What some people irreverently call the Big Bang. I don’t use that phrase, because it was originally used by people who didn’t believe in it and were trying to make it sound stupid. Anyway, that boundary condition needs to be adjoined to the fundamental equation if we are going to get the complete laws of physics. And then also we have a candidate. Jim Hartle, my colleague and collaborator and 25 years ago my graduate student here at Caltech, but now a professor at the University of California at Santa Barbara, and Steve Hawking, with Cambridge, who has attracted a lot of attention with that book called A Brief History of Time, that so many bought and have claimed to have read. The two of them, Hartle and Hawking, formulated a number of years ago a candidate for that initial condition of the universe. And it might be right also. We don’t know, but again it is the kind of thing that might possibly be right. Their condition is particularly interesting because their condition utilizes the same formula that would describe the unified quantum field theory of all particles and all their interactions, which would mean, if they are right, that there is only one fundamental law. The equation and the boundary condition would both be given by the same formula. Which is really exciting. Anyway, so much for the fundamental law. We may be very close to knowing. But that’s not all there is, because…

The description of the universe in quantum mechanics is a probabilistic one. The fundamental laws do not tell you the history of the universe. They tell you probabilities for an infinite set of alternative histories of the universe. And what we see about us is the result not only of the fundamental law, but of all those many throws of the quantum dice that determine the specific features of the universe. So we are asked, for instance, the statistical distribution of the shapes of all the galaxies of the universe. It is probably determined by the fundamental laws. The shape of our own galaxy, the specific shape of a particular galaxy, is probably also the result of a lot of accidents, and the same is true of a particular star, like the sun. And the particular planetary system, like the system of planets around the sun. A particular planet, like the earth, is a product not only of the fundamental law, but also of an innumerable set, a very large set of accidents. The same applies to the evolution of life on the earth, which contains many features attributable to accidents that are, in principle, unpredictable. The same with particular forms of life, and the same with particular individuals. For example, every human individual is the result not only of fundamental laws, but also of a huge chain of completely unpredictable accidents. So that the rich fabric of the universe as we see it around us is co-determined by the fundamental law, and this long sequence of accidents. And to understand how that appears, we have to understand a whole different part of science, which is how a system that learns, or adapts, or evolves, can exist in the universe, and how it processes information so as to make some sort of picture of the universe. And we human beings, of course, are among those complex adaptive systems. Life as a whole can be thought of as a complex adaptive system. Parts of living creatures, like the immune system, can be considered to be complex adaptive systems. The brain, or the mind, which is the manifestation of the brain, can be thought of also as a complex adaptive system. Computers that are programmed to invent strategies can also be thought of as complex adaptive systems. All of these that process information in a particular way, seem to have a lot in common. I’m thinking a lot about that these days.

And you are saying that they all operate on a set of fixed laws but are affected in every instance by varying circumstances?

Murray Gell-Mann: That’s right. Varying circumstances, which is the result, at least in part, of long chains of accidents, completely unpredictable accidents. Now that’s true of the quantum nature of reality, that we have all these, in principle, unpredictable accidents. But even in the approximation of so-called classical physics, where the specific quantum effects are ignored, there is still the famous phenomenon of chaos. In non-linear mechanics systems, what chaos means, technically, is that the outcome in such systems can be infinitely dependent on the input. In other words, an infinitesimal change in the initial conditions can produce a finite change in the result. The modern rediscovery of that sort of thing is attributable in part to meteorologists. It is very important in meteorology that you can’t actually predict certain aspects of the weather very easily, because sometimes they are actually infinitely sensitive to the initial conditions.

We’re always intrigued by stories where people travel backwards in time to change one thing so that one outcome can be avoided. They always find that no, you can’t change that one little detail, because it would destroy history as we know it.

Murray Gell-Mann: That’s a science fiction situation. So far, we can’t say that such a thing actually happens. But yes, in science fiction there is a famous puzzle of what would happen it you could travel backward in time. If you change things so that the past was then incompatible with the present, then you couldn’t get back to the same present. So in some science fiction stories, as you know, the situation is resolved, by having the character take actions in the past which made the present possible. So that instead of shooting his own grandfather before the grandfather had progeny, which would be really dangerous for the present, it turns out the main character is his grandfather. He has gone backwards in time and intervened by siring his own father, for example. But by that means the science fiction writer has created a consistent loop, a self-consistent loop. So far that’s just science fiction. It has no counterparts in reality as far as we know.

When you were growing up, was there an experience or an event that most inspired you?

Murray Gell-Mann: I loved the idea of structure in the world — and the power of theory — from a very early age. I was very excited at discovering relationships among things. I loved that. It was great fun, and continues to be great fun. I think it’s great fun for everybody who does it. It’s just wonderful. If people have lived without it, they should probably pick it up, because it’s really splendid to look at the world in terms of connections, relationships. So many people just look at facts as disconnected objects, and they are not like that at all. There is an intricate pattern of interrelationship among things.

What was the first instance in which you remember discovering that interrelationship, that thinking “ah-ha!”

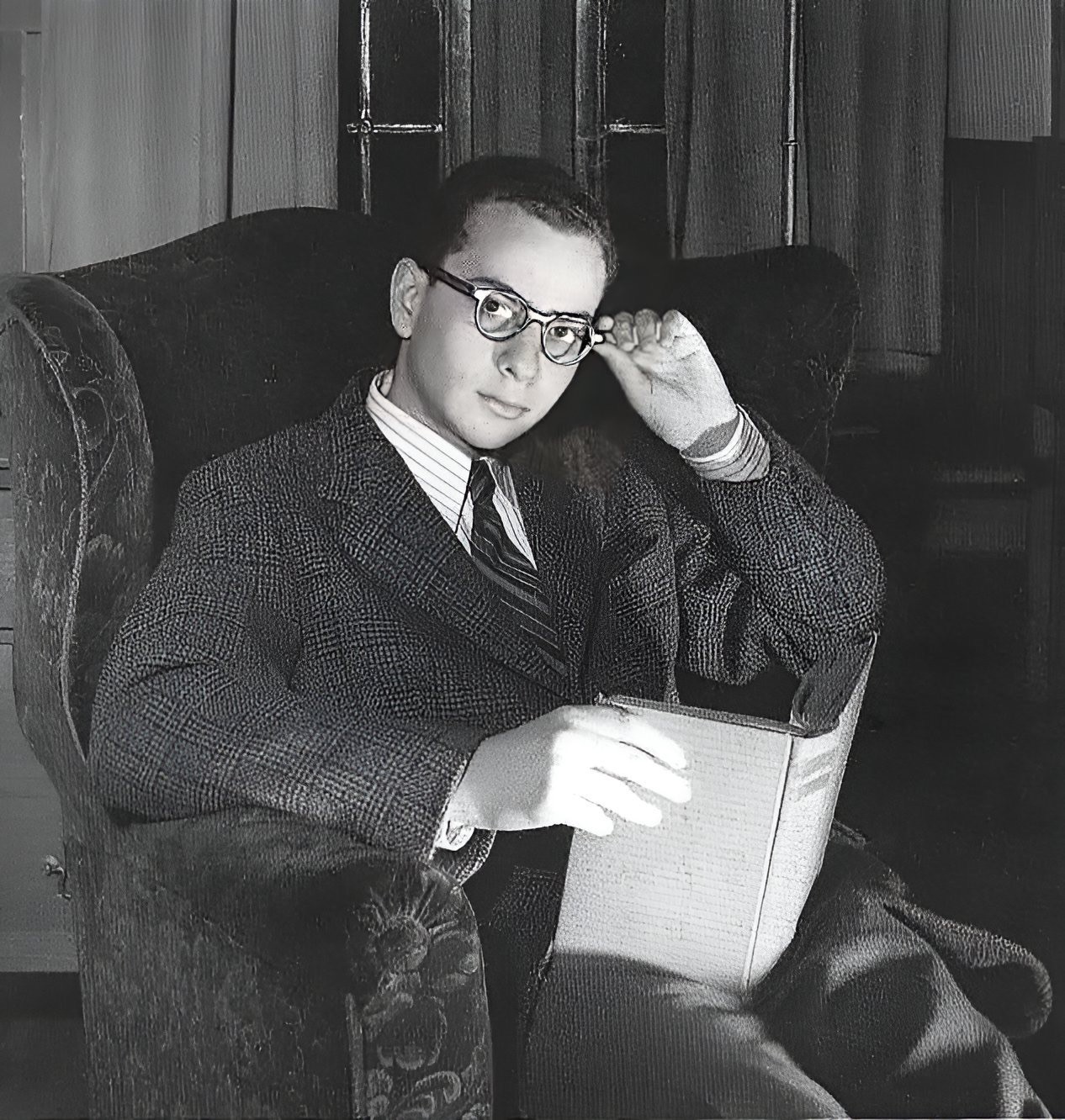

Murray Gell-Mann: Gee, I don’t know. There were so many when I was a little boy. So many it is hard to remember what the first one was. Something that was very important came much later. When I was at Yale as an undergraduate, I learned a lot of math and physics rather formally, and of course a lot of other subjects as well. I loved some of the history classes and a number of other things, but the math and physics that I learned, I learned almost by rote. I learned it in a very superficial manner. There was some of it I understood deeply, but most of it I understood on a rather superficial level. But it was sufficient to pass all the examinations and get very high grades and so on. A student is, in many respects just a machine for getting grades. So I did that sort of work as an undergraduate, without really getting deeply involved in the understanding of what I was doing. Then…

I went to graduate school, MIT, and there, a few weeks after I got there, I attended the Harvard-MIT theoretical seminar, which was held that day at MIT. And I didn’t know what a theoretical seminar was, I thought it was something like a class. I looked around for some teacher to please, which was after all the point of class. But it wasn’t like that. There were big-shot professors sitting in the front row, and there were all sorts of other people, post-doc graduate students, younger professors, and so on scattered throughout the audience. Anyone who was interested in theoretical physics in the Cambridge, Mass., area was there. The speaker was a Harvard graduate student who was about to get his Ph.D. He talked about his dissertation. And in the dissertation, he attempted to demonstrate, approximately, something that everybody believed to be true, which was that a spin — angular momentum of the lowest energy stage of a nucleus called Boron-10 — was one unit. The ground state, so called, or Boron-10 had a spin of one. And what he did was to use so called tri-way functions, and vary them. Try to get the lowest energy possible. And by this approximate method, he found that the lowest energy seemed to come out with a tri-way function of spin one. Which confirmed what he was trying to show. It wasn’t a rigorous proof, but it was a significant bit of evidence. And then he finished his talk, and I wondered what would happen. Would the professors in the front row give him a sort of grade? Classes was the only thing that I understood. Grades and pleasing the teacher, that sort of nonsense. The real workings of science was something I understood only from a great distance, from reading history books and so forth. What happened was that the big-shot theoretical professors in the front row didn’t say anything, but a little grubby man got up from right next to me. Somebody who looked as if he had crawled out of the basement at MIT. And he said, “Hey, duh spin ain’t one. It’s three. Dey measured it.” And suddenly it occurred to me in a sort of blinding flash that the job of the theoretician was not to please the famous professors in the front row, but to agree with what this grubby man found in the laboratory! Agreeing with nature is the main thing. And suddenly I had a real idea of what a theoretical scientists is, and what the point of theoretical science is.

That’s a great story. I take it this person had in fact been in the basement doing research.

Murray Gell-Mann: Yes. I don’t think it was his research he was talking about. But he had read about it, heard rumors of an experiment which measured it, and it was not what people thought it was going to be. It was quite a burden, actually. Because at that time, there was a new theory of the structure of light nuclei, the so called “shell model,” J.J. Cuppling’s shell model with which this new value agreed. But nobody was talking about that theory. They were talking about a bunch of older ideas at this seminar. A few weeks later, one of the people working on that new theory came to give a seminar. And that talk was completely compatible with Boron-10 having three, in fact it predicted that Boron-10 would have a spin of three. So I began to have a real idea of how these things work.

You mentioned a favorite history professor as well.

Murray Gell-Mann: Well, there were a number of history professors at Yale. There was one that I liked very much called Hajo Holborn. His classes were splendid. But there were a number of others that I liked as well.

What was so special about history in general, and that class in particular?

Murray Gell-Mann: I’ve always been fascinated by history. Most of my reading has been about history, still is. History and pre-history. History and archeology. It is still true. What I liked about him was that he tried to acquaint ordinary students — most of them were not professional historians and weren’t going to become professional historians — he tried to acquaint them with how history actually operates. What are the primary sources? What do we really know? How much is speculation? How much of what people conventionally say about history is actually false, and so on? I loved that. He tried to cut through the conventional accounts of history that we all absorb in elementary courses and ordinary reading, in newspaper articles and so on, to get back to what really happened, what was really going on. He emphasized that the way historians find that out is by studying the actual primary sources, not just reading one another’s books.

Going to the lab, so to speak.

Murray Gell-Mann: A very similar thing, yes. Going into the lab instead of just arguing about theory in the absence of fact. That’s right.

What about the person who inspired you most as a young man? You talked about your brother. Was there someone else who had a major impact on your thinking?

Murray Gell-Mann: Not particularly. There was a teacher at school who was fun. I don’t know if he had a big impact on my thinking, but he was a lot of fun. His name was Dow Bunyan Bean, and he had a Doctor of Divinity degree, from some place in the South. I think he came from Georgia. And he had lost his faith and he had lost his interest in religion, and had become a secular high school teacher. Everybody called him Doc Bean. He was marvelous. He was full of animation. He was relatively old at that time. At least we kids considered him relatively old. But he was very lively, jumping around, raising his voice, lowering his voice in all sorts of interesting ways, with a racy line of talk about whatever he was discussing, and suddenly stopping and asking somebody a question to make sure the person was listening. Writing down some little grain in his book. He was lively, and it was marvelous. And if he didn’t know something, then he would immediately send whoever asked the question to the library to see what was known on the subject. I thought that was particularly splendid. Not that, of course, everything is available in a library. Lots of things are simply not known, or maybe unavailable in a high school library. But the fact that he wanted to push every inquiry as far as it could be pushed with the local resources, that really impressed me. I thought that was great. And every time anybody was curious about something, either he could answer it, or somebody else in the class could answer it, or else we went and used whatever resources where available to try and find out the answer.

It also seems that you picked up from him the notion that learning can be fun.

Murray Gell-Mann: No, I always thought that learning was fun. Many people think of learning as connected with school, and I never did. For me, learning was something you did, and school was sort of an ancillary piece of equipment. School was never the primary place of learning for me. I did learn things from time to time at school, but it was not the main thing. I have spent my life learning. School was just a little piece of it.

Was that because you had your brother leading the way?

Murray Gell-Mann: Yeah, but I didn’t need my brother. My brother started me out in a lot of things, and my father to some extent, but once they did, then I could read, or go to a museum, or read a newspaper, go to a film. There are all sorts of different ways of learning. Listen to the radio, or whatever. But I felt that learning was a life-long experience, and school was incidental. It’s a pity that some people I know were put off particular subjects, because they had teachers in those subjects who were uninspired. My late wife, Margaret, for example, had a history teacher that turned her off history for decades, many decades. It’s sort of a shame, history is such a glorious subject. Finally, as an adult, she began to realize history had a lot of appeal. She had lost 30 years or something, because of this stupid teacher. Now, that could never happen to me, because I didn’t form my opinion of subjects according to what some teacher said. I already had some acquaintance of the subject. If the teacher didn’t teach it well, I just turned off the teacher, but not the subject.

When you got into college, and into your graduate studies, how did things finally come together for you? When did you know what direction you wanted to go in?

Murray Gell-Mann: I didn’t. I just drifted along playing physics because I had started physics. It was nice. I enjoyed it. I liked it. I became very ambitious to learn more and do something in physics. As I explained, when I got to graduate school, I began to understand what it meant actually to learn, to do something, rather than just to study and pass. And it was fun. I went on and went to the Institute for Advanced Study for a year after graduate school, and began to teach. My first job was at the University of Chicago, and then I came here. It was all very straightforward.

The teacher at MIT, my teacher, who is still alive, Victor Weisskopf, was a wonderful, inspiring person — is still a wonderful inspiring person. He is really a splendid person, and working with him was marvelous. First of all it was fun, but second I really learned something. Not a fact or a theory particularly, but I learned a principle, which was that fancy mathematics doesn’t have any value in science for it’s own sake. It may be useful to introduce some new mathematics, some fancy mathematics, because it helps you to get the answer. Helps you to formulate a new theory. Helps you to solve an old one. But just doing it for it’s own sake, just snowing people with mathematics is not a good idea. You should use methods that are as simple as possible, given the richness of the material, the depth of the theory that you are applying it to. That was very important, because graduate students are frequently impressed with formalism. And Victy just refused to be impressed with formalism. He said, “That doesn’t matter. It’s just formalism.” What matters is making a new discovery, a new theoretical discovery, not with just improving the formalism. Improving the formalism may prove useful for making a new discovery, and in that case it’s fine, but otherwise it is not to be valued. Don’t be impressed by formal developments, be impressed by real developments. That was very important for me.

How much of a role did hard work play, versus luck, in the way things have gone for you?

Murray Gell-Mann: That’s a very easy question. I have never done any hard work in my life. I wish that I were capable of hard work. Maybe now, finally, I can do some hard work. All my life I’ve been terribly lazy. And it’s very bad, these last few years, because I’ve taken on much more than any human being can possibly do. Say I take on 50 times what a person can do, and I work at, say, two percent efficiency. That puts me behind by a factor of 2500. Every day I fall several years further behind, and that’s painful. That’s the most painful aspect of my life. If I could reduce the commitments, or increase the efficiency, or both, I would be so much happier. But I haven’t been able to do it.

But you’ve been so successful.

Murray Gell-Mann: Well, here and there, something works. But, you know, that’s such a tiny fraction of all the things that I could do, or should have done, might do, try to do. Some people are really hard workers, they really get things done. Not only are they hard working, but they are effectively hard working. So they’re efficient. They know how to organize their lives and they actually get things done. So all my successes, whatever they are, are at the margin. There are a few things that I have managed to get done. They’re just a tiny number of so many things that I would have liked to do, probably could have done, if I had been more sensible.

Could you give us an example of something that you wish you’d done?

Murray Gell-Mann: Well, in physics, for example. I could certainly have followed up my work on quarks, and worked on quantum chromodynamics much earlier that I did. Lots of things I could have followed up on, sooner, more effectively. My attention was scattered. I didn’t work hard enough.

How much of that was also the desire to have a personal life?

Murray Gell-Mann: Well, that’s true. No, I don’t regret having a personal life. I don’t regret what little time I managed to spend with my wife and children and so on. No, that I don’t regret at all. But a lot of it is really wasted. Reading is perhaps the worst. Reading is a terrible addiction. There’s a lot of talk now about drugs and alcohol and so on, but reading is really bad. Andre Gide talked about “Ce vice impuni, la lecture” — “That unpunished vice, reading.” If somebody is a real reading addict, he just reads. Really, you try to read the newspaper every morning. All the junk, all the unimportant junk in the newspaper. The comics, the editorials, and so on, and you read aspirin bottles and anything. It’s just terrible.

Cereal boxes?

Murray Gell-Mann: Well, I started on cereal boxes. That was not a waste of time, to learn to read. No, it was a cracker box, Sunshine. No, you start to read a cracker box, and thereby learn to read, that’s not so bad. But later on, just reading cracker boxes over and over again! It’s a terrible addictive practice. A compulsion. Anyway, I’ve wasted a tremendous amount of time reading junk. That’s just one example.

But you’ve processed a good bit of it, haven’t you?

Murray Gell-Mann: No, I don’t think so.

Well, it gives you so many things to talk about, you probably inspired your students.

Murray Gell-Mann: I don’t know that I inspired them. I certainly digress a great deal. I’ve never asked my students what they think of all those digressions. I think they just ignore them. I think they just pass right by. But I’m not sure. Sometime I should have somebody ask the students what they think of the digressions. There certainly are a lot of them.

Perhaps those digressions are a reflection of your view that everything in this world is connected.

Murray Gell-Mann: It’s true. And I view culture as something that is unified. I don’t like the idea of breaking it up, artificially, into art, science, social science, humanities. Then specific fields — immunology, nuclear physics, cultural anthropology, and so on and so forth. Because there are so many important things that connect one field to another, and principles that transcend many of these fields. And for me, it’s always been true, every since I was little, and my brother and I used to look at the world together, that it’s all part of the same fabric. It’s all part of human culture. Part of the way we look at the world.

You liked the daring historian who didn’t stop when time did.

Murray Gell-Mann: Of course the future is very interesting. I just got through meeting with a group of people that a couple of us have organized here at Caltech to hold a symposium next year on the future. We just finished yesterday a preliminary conference on the same subject. It’s on visions of the sustainable world. Can we imagine what a sustainable global society might look like in the middle of the next century? Can we figure out what some of the transitions are that we would have to undergo as a global society, in order to get from here to there? And what are the trends in the world today that seem conducive to making those transitions? I’m also organizing, with some other people, a big research project on the same subject, visions of the sustainable world.

Clearly with an interdisciplinary approach.

Murray Gell-Mann: Oh yes, everything. Natural science, social science, law, medicine, anything you can think of.

If you were a young person these days, what would you be interested in? What would you see as the most exciting areas of inquiry?

Murray Gell-Mann: I think what some of us are trying to do today, which is to understand the general principles that underlie complex adaptive systems. All living things, sets of living things, computers that are programmed to solve problems and create strategies. The chemical reactions that preceded life, so called pre-biotic chemical evolution, aspects of life, like the immune systems of mammals, and complex adaptive systems on other planets throughout the universe, whatever they might be. The must all obey certain principles, fundamental principles of complex adaptive systems. They apply to all learning, adapting and evolving systems throughout the universe. What are those principles? How do those things work? How do they process information so as to learn, adapt and evolve?

But all those things are constantly changing.

Murray Gell-Mann: That’s right. The universe, the environment — if you want to call it that — of the complex adaptive systems is itself changing with time. Not only is it a time series, with certain probabilities for certain events, but that time series is changing with time. And furthermore, with many cases, the environment is itself an adaptive complex system, and is co-evolving, as well as just changing, with time. So you have two or more systems, both or all of which are evolving together. That is fascinating to study and to think about. These days, with the availability of large computers, one can begin to model such things. It’s far too complicated to approach analytically, at least to begin with, by writing down formulas and solving equations, but one can approach it readily by making models, computer models.

That has helped us move more quickly toward integrating a number of problems that cut across disciplines.

Murray Gell-Mann: The study of complex adaptive systems cuts across archeology and linguistics, economics, physics, chemistry, math, immunology, and so on and so forth. It just goes on and on. Computer science. That’s the kind of thing we’re doing at the Santa Fe Institute, which I helped organize. It is devoted to giving people from virtually all fields the opportunity to work together to understand how complex adaptive systems work, and other complex systems as well, but principally complex adaptive systems. And we bring people from all of these disciplines — psychology, mathematics, chemistry, anthropology, and so on — together for meetings, and we allow them, or encourage them, to form research networks. It’s very exciting. I do a lot of the recruiting for the Santa Fe Institute, for the science board which supervises the program, and also for individual researchers. Every time I phone somebody in some distant field, some famous, busy person, I know that person is going to say, “Well, what you’re doing sounds interesting, but I’m already fully committed, but don’t call me, I’ll call you.” But instead, in almost every single case, the person says, “When can I come? I’ve been waiting for this! I’ve been waiting all my life for something like this!” It’s very interesting. It’s apparently a real felt need.

You mean something that is not as restraining as the discipline they usually work in?

Murray Gell-Mann: That’s right. In a university, or an institute of technology, people feel, whether it’s true or not, that they must stick somehow to particular activities, and discuss things in particular ways. When they come to the Santa Fe Institute, they feel free of those restrictions. In one case, we had a seminar on the evolution of the human languages, which I helped to organize. We had five linguists from the same linguistics department, same university. Of course they all knew one another very well. But at the Santa Fe Institute, they had conversations they had never managed to have at home, because it’s a place where one is encouraged to make connections.

You mean to reach out in ways that you might not if you expect to be judged only within your discipline?

Murray Gell-Mann: Yes. They were actually all in the same discipline, the same department of the same university, but they were doing somewhat different things. At home they just each stayed at a position. I work on such and such and aspect, and the other says he works on such and such. At Santa Fe Institute, they began to argue about how you could put these things together, and to what extent particular grammatical universals, for example, were explained partially by one approach and partially by the other approach. So some sort of synthesis of the two points of view began to be formed, which the two colleagues had never done at home.

Is the Santa Fe Institute directed largely at behavioral science?

Murray Gell-Mann: No, not particularly. Everything. Math, natural science, behavioral science, even the humanities to some extent. We have a very good historian on the science board, and we have done two sizable workshops on the pre-history of the Southwest, which of course involved a lot of archaeologists.

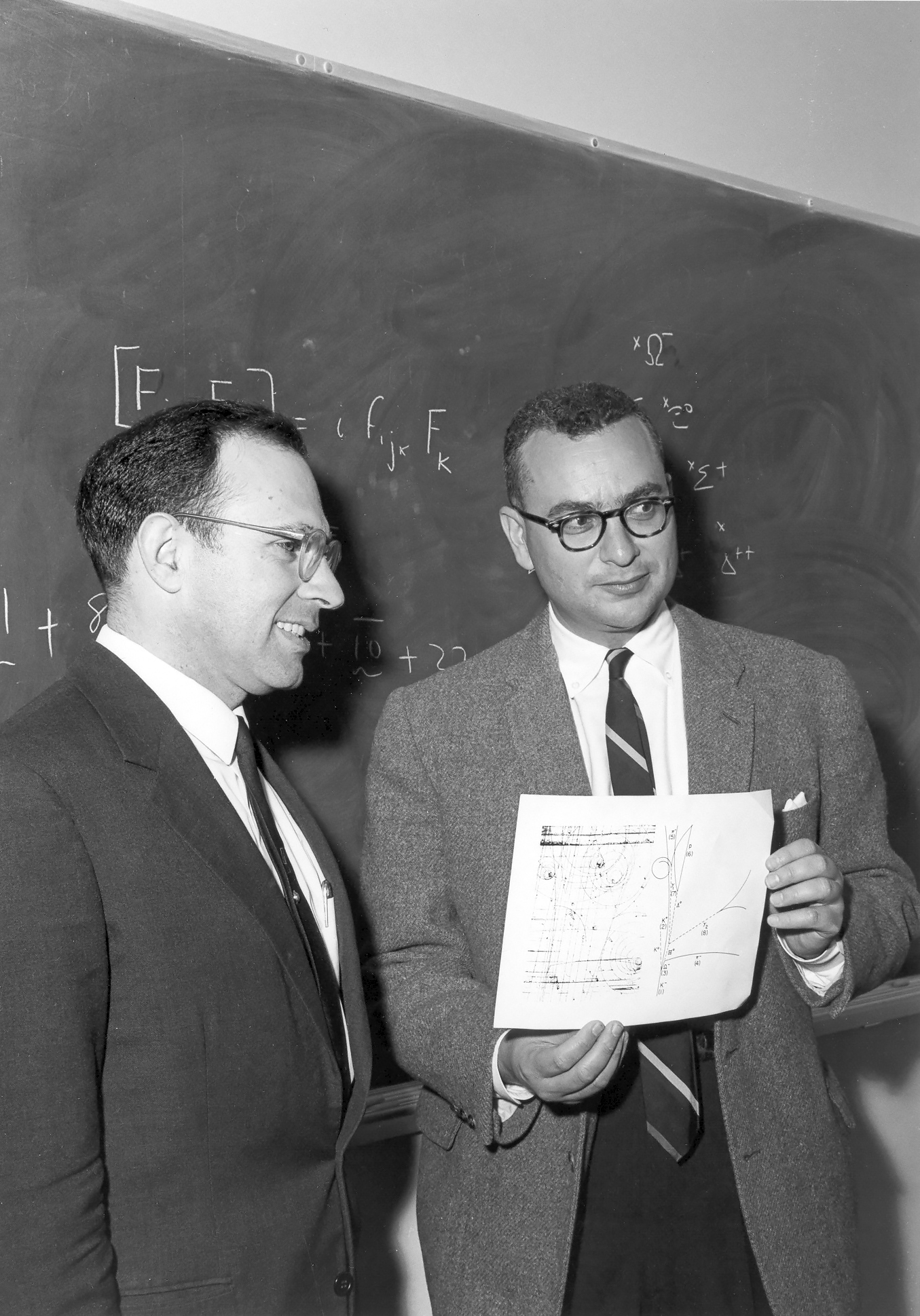

You made the pioneering study of what physicists call the “strangeness” of subatomic particles. In context, what does that mean?

Murray Gell-Mann: It’s just a name, which I gave actually, to certain particles. They were called peculiar — or curious, or strange or something — particles because they were produced copiously in reactions. Initially, they were observed in cosmic rays, so the reactions were in the atmosphere. Later on, the reactions were in the laboratory. But in either case, they were produced copiously. But they took what, by our standards, is a long time to decay. Ten to the minus ten seconds, for example, is a very long time. A short time would be ten to the minus 24 seconds. So, that’s one over one with 24 zeros. One over one with ten zeros is obviously a very long time compared to that. And it wasn’t understood initially, back in 1952, how they could be produced in large numbers and take a long time to decay. I explained it with this so called strangeness theory. But I just gave the name to these particles, the strange particles, people were calling them things like that – peculiar particles, strange particles, curious particles. Because they had this apparently paradoxical behavior of being produced strongly and decaying weakly. And I explained why that happened and facetiously gave the name strangeness to the quantum number that was involved. The quantum number was conserved in the production, but violated in the decay. So the production could be done by the strong interactions and could be strong. And the decay went by the weak interactions, and thus the slump.

Is this an example of what you were talking about earlier, of the general laws interacting with varying circumstances to produce different outcomes?

Murray Gell-Mann: No, I wouldn’t say this was an example of that. In specific, reproducible, fundamental physical situations, one is just dealing with the consequences of the fundamental laws.

You’ve taken your scientific interests and applied them in other fields that a good many physicists don’t get interested in.

Murray Gell-Mann: In my case, those interests preceded my interest in physics.

And survived them.

Murray Gell-Mann: Yes.

Do you think we’ve learned as much about ourselves, about people as complex adaptive systems, as we have about the world around us?

Murray Gell-Mann: No, I don’t think so. It’s much harder. Complex adaptive systems are a much more difficult to study than the fundamental laws of physics, for example. And among those, the study of human beings is fairly complex. The study of human beings is a very difficult thing. We haven’t made so much progress on it because it is more difficult. The fact that we are studying ourselves, in that case, perhaps may also make for some difficulty.

It is easier to study the interaction of particles than it is the interaction of human beings.

Murray Gell-Mann: Oh, for sure. My forthcoming book on all these things is called The Quark and the Jaguar: Adventures in the Simple and the Complex. The “simple” refers to the fundamental laws of physics. The “complex” refers to things like us. And that’s perfectly correct. It may not be how the person on the street prefers to state it, but the fact is that the fundamental laws of physics are very simple. It may take a couple of years to learn the right notations and so on, but they’re intrinsically simple, and that’s not true of complex adaptive systems.

You once described your marriage as having made you a much more whole person. Did it change your outlook in some way about life?

Murray Gell-Mann: Well, I like very much sharing experiences with somebody I love. For me it’s a very important part of life. I can’t really enjoy something properly if I just do it or see it, or know about it, or hear about it myself. Sharing with a loved one is a very crucial part of living. And Margaret was a very charming person, and very witty, and just a very pleasant companion. A very exciting companion.

There are some times that we get so wrapped up in our work, especially in theoretical endeavors, that one could get very preoccupied with that. Did she help bring you back to a broader reality?

Murray Gell-Mann: Probably. Probably she did. But I would do that anyway. The main thing is to have some wonderful person to do it with. But I would want, in any case, to come home and do other things. The question is, is there some splendid person to do it with? Somebody to raise children, and dogs and hamsters and snakes and so on with. And to engage in all sorts of other adventures, including intellectual.

You mentioned earlier that you had done a bit of exploration, and that you might have wanted to do more. What have you done, and what did you want to do?

Murray Gell-Mann: I would have liked to do pioneering exploration, in areas that very little study had been done, and make new discoveries in natural history, or conceivably in archeology. It’s a romantic dream of a great many kids, and I still have it. I’ve never really done it, but I’ve poked around in an awful lot of remote places in the last few years. And that’s been fun. That’s been a lot of fun. And it’s been extremely educational. It’s also helped me a lot with my activities in conservation of biological diversity. Because most of the problems of conservation and biological diversity are in the tropics. It’s where most of the biological diversity is, and it’s where the biggest problems are. Problems of rapidly burgeoning populations, poverty, and so forth. So the biggest treasures of biological diversity are in the tropics, and the dangers are the greatest in the tropics. Of course, nothing can be done about those without simultaneously working on the living conditions of rural people in the tropics. One has to build a kind of structure in which those people, in their search for a better life, is in harmony with protecting the biological diversity, so that they have a stake in it, and perceive that they have a stake in it.

Poking around in so many of those places over the last eight years or so has helped a lot with my work on that. I’ve devoted a lot of attention to that whole area.

Do you find something particularly exhilarating about going somewhere new and seeing how people live, how they relate and adapt to their environment, how they adapt to change?

Murray Gell-Mann: And seeing how the animals and plants in the area relate to one another. The extraordinary variety, and the relationships. Relationships in their taxonomy, and the relationships in their behavior, are both exciting. They form a system. Organisms aren’t just individuals, they form a very complicated system with all sorts of very complex patterns of interaction. I don’t claim to have studied those things very deeply, but even just the superficial study is extraordinarily interesting, and it’s been very valuable in my conservation efforts.

You’ve also had a lot to say about balancing ecological systems with economic systems, with trying to live within your environment to get a better life.

Murray Gell-Mann: It’s very important when you do that, that economics be generalized to include the values of, for example, biological diversity and many other things. It’s all part of the program of trying to get closer to true costs, and true values in economics. Now most very advanced researchers in economics agree that that sort of thing in principle is desirable, and they do some theoretical work on it. They have various constructs, like the social discount rate, which measures debt between the generations, the so-called inter-generational equity. Of course they have externalities. If something like the air, or the oceans, or the forests are treated as free goods, it obviously is not true. So you try to charge for them in some sense, theoretically by treating them as externalities, and internalizing them, which means that you actually do charge. Assign a value. Anyway, all of this is done in the textbooks, and the cost of information is considered. But in practice and economic practice in so many places, lending organizations, and so forth, most of this is forgotten, and approximated by zero.

Value is assigned to those things that have value in some trivial sense. Like costs, or trivial costs, that are very easily quantified, and all the things that are difficult to quantify are put equal to zero. And I have been upset by that for 20 years, and for 20 years I’ve been trying to figure out ways to fight it, and to make propaganda against it, to get people to improve their ways of thinking and their ways of behaving. The survival of our society on this planet, and survival of the other organisms on this planet, is very much bound up with how soon we can learn to charge true cost, and depreciate true values, and combine those things with the usual economic calculations. The usual economic calculations are caricatures.

You mean the things that are considered to have value are the things you have to write a check to pay for?

Murray Gell-Mann: Right. And the other things are for convenience but equal to zero. As I said, the brilliant economist will of course admit that is not correct, but the problem is to do something about it in practice.

If you don’t do something about clean air, for instance, you’re looking at huge costs for health concerns. There are all sorts of things we don’t assign a dollar figure to, but that clearly have value.

Murray Gell-Mann: That’s very true. But these huge costs are often not correct. They leave out some other things. They assume free markets, and in fact ,often the market isn’t free, there are all kinds of market impediments. Again, I don’t mean the brilliant economist. But the people who do these things in practice often make these errors, and if you remove market imperfections, frequently you find the costs are very small, or negative. That you actually make money. For example, saving money in many cases will make money. And reducing carbon dioxide emissions will in some cases make money rather than cost. But you will still find lots of people who will calculate that it’s very expensive and will cost a lot. I’m not talking about making money in conventional terms. I’m not talking about making money in terms of true value. But just in actual money. Anyway, this generalization, and correction and refurbishing and reform of economic calculations is very important.

This is a critical aspect, you think, of preserving our future?

Murray Gell-Mann: Yes. One of the most critical. Perhaps the most critical aspect.

Otherwise the bottom line will be a perversion of reality.

Murray Gell-Mann: Yes. It is already. It’s very much a perversion.

When you received the Nobel Prize, what were your feelings? What did you say upon receiving the Prize?

Murray Gell-Mann: What did I say? I didn’t say anything. You don’t say anything at the moment. When the King hands you the prize, you say “thanks.”

Really?

Murray Gell-Mann: Tack själv. I don’t know. Later on that evening you make a speech, a brief speech. I just said a few words, partly in Swedish, partly about… I mentioned the new photographs of the Earth from space, showing a blue planet, and how precious our blue planet is. We don’t know of any good place to live anywhere close by, other than this blue planet, and we ought to take care of it. And I congratulated the Swedes, in their own language, on proposing the first U.N. conference on the environment, which was held three years later in 1972 in Stockholm. That’s the sort of thing I talked about. I said a few other things. I said the beauty of the laws of physics and the beauty of nature and so on, were not to be different things, but aspects of the same thing. The second U.N. Conference on the environment, twenty years after the first, is to be held in ’92 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and that will be a very exciting discussion there, of the greatest importance for the future. There’s a man who’s making a film, a 90-minute film to open that meeting. He’s the same man who made the film shown at the first conference in 1972. I was just meeting with him, last night and the night before, to discuss some of the things that he ought to film. I may even appear briefly in the ’92 film, in the forests of Brazil. That is one of the most polluted places in the world, not very far from São Paulo. I saw it in 1985. It’s exciting that the Brazilians are trying to preserve it now, what fragments are left of the Atlantic Forest that stretches from near the coast, from the North of Brazil all the way down into Paraguay, and even a few kilometers into Argentina.

By the time you received the Nobel, you had gained a great deal of fame and attention. What impact did that have on your wife and family?

Murray Gell-Mann: My wife liked it. I knew that. She really liked it. She enjoyed the whole thing very much. Not the publicity, particularly. She was not anxious for publicity. But just the whole series of events appealed to her a great deal. We had a wonderful time going to Stockholm together. It was really nice.

Over the long term, was it something that affected your family?

Murray Gell-Mann: My daughter and my son reacted oppositely, on the morning when they notified us. You know, how you get a call from somebody. Nowadays it’s from the Academy, but at that time it was from some news media, at 3:30 in the morning here in California. Well, I was pleased to hear that I had gotten this thing. I was not pleased to be deprived of my sleep, because people kept calling. And finally Margaret said we should get up and get dressed and she would make coffee, because obviously we were not going to get anymore sleep, and some reporter or photographer might be coming any minute from the Los Angeles Times. So we did, we got up, she made coffee. The reporter and photographer showed up from the Los Angeles Times. My daughter dug deeper under the covers, didn’t come out for hours. She didn’t want to have anything to do with any of this. But my son, who was seven years younger, he was six years old at that time, was delighted with the idea that a reporter and photographer were coming to the house. He wanted to be photographed and he had his Halloween pirate costume, because it was the day before Halloween, October 30. So he put it on, he got all dressed and put on his pirate costume and came out, and of course the Los Angeles Times photographed him! The next day, smack in the middle of the front page of the L.A. Times, in fact right on top of the front page of the L.A. Times, was Nick in his pirate costume! But it was a mixed blessing for him, because he hadn’t calculated that everybody got the paper, and that everybody in his school would see his picture on the front page, and that they would kid him about it.

That was a part he hadn’t anticipated.

Murray Gell-Mann: The opposite reaction of the two children was very curious.

They didn’t become theoretical physicists, did they?

Murray Gell-Mann: No, I didn’t particularly want either of my children to become anything in particular, anything special. Just something that would be satisfying, and if possible, something great. But not anything in particular.

You didn’t want them to follow in your footsteps?

Murray Gell-Mann: Not particularly. I wouldn’t have objected, but I wouldn’t have wanted it particularly, either way. Anything: art, science, business, whatever.

The road to success is often a winding one. Were there particular obstacles that you encountered along the way?

Murray Gell-Mann: No, not really. Everything has always gone wonderfully for me. All the obstacles were internal. Inefficiency, neurosis, all the obstacles have been internal. I can’t really think of any obstacles that were placed in my path. We’ve had the most wonderful things happen to me. A full scholarship to Yale, for example. Donated by somebody whom I met later, became a wonderful friend. Trini McCormick Barnes, it was called the McDill McCormick Scholarship. It was anonymous, I didn’t know who had donated it. But it was Trini Barnes in memory of her brother, who had died young. And it paid for everything at Yale. All my expenses. It was an extraordinary scholarship. It was the only one like that, and it was the only one that would have permitted me to attend the University there. Fantastic luck. Then I had some trouble with graduate schools, and I hadn’t wanted to go to MIT, but it turned out that MIT was splendid. Especially because of Victor Weisskopf, who was my advisor, my teacher. So that also was terrific. Everything has gone very, very well. Always. And all the difficulties have been self-generated. Except the death of my wife. That of course was tragic, and not something that I brought on.

How much impact did that have on your work?

Murray Gell-Mann: Oh, it had a lot. While she was ill, I didn’t do much work, very little. After she was gone, I began to do different things.

You talk about the internal obstacles. You talked earlier about being lazy.

Murray Gell-Mann: Well, laziness isn’t all. I think a great deal of neuroses of one sort or another, a great many cases of compulsive, irrational, maladapted behaviors, such as so many of us have, the reading addiction is only one part of it.

Did you worry about failing at all? Your chosen area of theoretical physics is extremely competitive.

Murray Gell-Mann: When I was a kid, when I was a graduate student, I worried about failing. And not only did I worry about failing, but I worried that if I actually did something, then it might turn out to be a failure. And if I didn’t do anything, then I wouldn’t have the comparison of what I was doing with what I ought to be doing. So lots of graduate students go through that. It keeps them from doing work for a while. But finally I did some things. I wrote a dissertation and I worked on other matters. The problem at that time was that I didn’t understand what was new research. So a lot of ideas that I had were actually worth publishing and worth discussing with people. And I just dismissed them as trivial. I though, well, this is silly, everybody must know this, everybody must know that. In fact, they were new and not totally silly points. A lot of them actually. I had a lot of ideas which I could have simply followed up, written up, and so on. But I didn’t realize what a good idea it was. In fact, I’ve often had that problem.

Because it seems so obvious?

Murray Gell-Mann: Yes. And, you know, why bother to call attention to something, that’s just some very simple idea. But actually, simple ideas are often quite important. And it frequently happens that people haven’t thought of it.

It makes you wonder how many times people have dismissed things that have occurred to them.

Murray Gell-Mann: Or dismissed other people’s things. Yes, it happens very often. I know it happened to me.

Other people dismissing your ideas?

Murray Gell-Mann: That too, but mainly that I dismissed them myself. I just didn’t realize that they were worth mentioning to the world.

Did you also have doubts about your work along the way?

Murray Gell-Mann: I had doubts that I would ever do anything important. In certain cases that keeps you from sitting down and trying anything, because then, as long as you haven’t tried, you can figure, “Well, if I had tried it would be okay.” So yes, I went through a little of that in graduate school. I’ve had a lot of problems writing things, because I’m a perfectionist about writing. Again that I don’t sit down and do it, because I worry that if I do it, it will be imperfect, but if I don’t do it, I can always imagine that it would have been perfect if I had done it. So that was a problem. When I was supposed to be writing my dissertation, for example, at MIT, I read the Tibetan Book of the Dead.

It’s like cleaning house right before final exams. Something you haven’t done in six months, but suddenly it must be done.

Murray Gell-Mann: It must be done right away, that’s right. I still do that kind of thing. It’s nerve-wracking.

Do you ever get bored with your work? I get the sense that you see science as a game to some extent.

Murray Gell-Mann: If I get bored with one thing, there are always 50 other things that I’m doing. I’m involved in so many activities, I can scarcely be bored with all of them at the same time. But the easiest is to say, “Well, since I have so many things to do, I won’t do any of them. I’ll sit here and read this newspaper.”

What do you do to keep fresh and creative, to renew yourself?

Murray Gell-Mann: Goodness, I never thought of that. Associate with good people, I think is the best thing. Associate with amusing people, lively people, people who are young, or at least young at heart. I still think of myself as 29. The principle is you pick an age you like, and stick with it. So, I’m still 29.

Probably, I probably can do things better than I could then. Like walking, and climbing hills, and running. I’m probably in better shape than I was at age 29.

And you probably know more about what’s important and what isn’t.

Murray Gell-Mann: Yes, and if I could only act on it, everything would be great.

Other than the ones you had talked about, is there some quality, some attribute, that you have always admired in others, that you don’t have.

Murray Gell-Mann: Well, I just described it. Getting things done. Some fraction of them I get done, but it’s a very small fraction. It’s so obvious that I could do so much more, if I didn’t have all these silly problems of addictions and so forth,

On the other hand, without that breadth of interests, you might not see all the interrelationships between different fields.

Murray Gell-Mann: I guess that conceivable, but I don’t think so. Another thing that would probably be a good idea would be to cut out certain things in order to devote more attention to the rest, do a thorough, good job on them.

When your attention is fragmented too far, you can’t really have deep and good ideas. If you, for example, if you try to do science, but you become deeply involved in business, let’s say. Then what matters is what you think about when you wake up in the middle of the night. If you wake up in the middle of the night thinking about the balance sheet, then you are not doing science. Because science, theoretical science at least, consists of waking up in the middle of the night with an idea for your theory. In other words, the parts of the mind out of awareness are chewing on the wrong thing. And they can’t chew on everything. So your creative skills are rationed in a certain sense. You can’t have them in every field. And what you are really working on, you can tell, is what you wake up in the middle of the night thinking about.

What is the responsibility of scientists as you see it? What responsibility do you feel, to deal with the larger problems of society, beyond the field you are in? You’ve certainly addressed many of them..

Murray Gell-Mann: I do a lot of that, but I think that one has to be very careful about it. First of all…

Just because somebody is a physicist doesn’t mean that person has any particular understanding of society, or the future, or the way things are going, or any particular authority to discuss such matters. So one has to be careful, saying that because I won the Swedish prize in physics, I can now make a pronouncement on all sorts of political subjects and so on. I think that one has to be very careful of that. But just because one has won the Swedish prize in some scientific subject doesn’t mean that one has to shut up either! It’s just that one shouldn’t abuse, I think, one shouldn’t abuse the privilege excessively in having this sort of title by sounding off on all sorts of things without thinking deeply about them. But if one joins with colleagues from many other walks of life, many disciplines, to think deeply about some important issue facing humanity, and then one says something about it, particularly together with those other people, I think that’s very good, and should be greatly encouraged. But that is quite different. But when one says something, again, it should not, I think, be excessively polemical. It can have a polemical streak to it. Otherwise it might not get much publicity, people may not pay much attention to it. I think that scientists have some responsibility to make more or less responsible statements about things, rather than things that are merely shrill and polemical. And, also, they should initiate wherever possible, together with these colleagues from many other fields, serious discussions and serious research on issues facing the world. Not just off-the-cuff pronouncements. And anyway, that is what I have tried to do. I have tried to help organize such efforts to think deeply about things, together with colleagues from a great many sectors.

Do you feel there’s been too little of that?

Murray Gell-Mann: Much too little.

We wanted to ask you about some of the scientists you’ve known who took controversial stands on public issues. Edward Teller, for example.

Murray Gell-Mann: Well, he’s been involved on the wrong side of a lot of larger issues, yes.

There were many people who had no qualms about working on the atom bomb because of the circumstances, but they thought that developing the hydrogen bomb was a different thing entirely.

Murray Gell-Mann: They were entitled to their opinions, and they should not have been persecuted for their opinions. They should not have had their clearances removed by some perversion of the security apparatus because of a conspiracy by Edward and Louis Strauss, and various other people, Air Force people, and so on. I think that was a crime against Robert Oppenheimer. He was entitled to his opinion and he was entitled to propagate his opinion. Making him out to be some sort of enemy agent because he had a different opinion from theirs was terrible. However, I personally supported, at that time, and still do, the development of the thermonuclear weapon. I think at the time when Stalin’s Soviet Union was obviously doing the same thing — and we know who was doing it too. Sakharov and “Ya B.” (Yakov Borisovich) Zel’dovich, my friend “Ya B.” Zel’dovich, and Kurchatov, and so on. At the time when those people were doing that, I think it was not much alternative to our doing it in this country. But I consider it conspiracy, evil and reprehensible to try to label Robert Oppenheimer as some sort of a fiend, just because he had a set of opinions different from theirs. Basically, his opinions were those of the Army. And theirs were those of the Air Force. And, as I say, I don’t disagree with the opinions of the Air Force, but I think there was no reason to try to make out somebody, who happened to agree with the Army instead, to be a fiend.

So you’re saying that was basically an inter-service rivalry?

Murray Gell-Mann: Basically, that’s what it was. Robert thought that it was very important to develop small fission weapons. I was never particularly fond of that idea. But he and a number of other people thought that was very important. And he thought it was very bad to work on the thermonuclear weapons, and in particular, he and a lot of other scientists believed that we could reach an agreement with the Soviet Union not to develop the thermonuclear weapons, so that neither side would have them. Conceivably they were right. I tend to doubt it, because of who was in charge of the Soviet Union at that time. But Stalin did die, of course, around that time. In 1953, by the time of the Oppenheimer hearing, actually, Stalin was gone. By that time, maybe it was possible to make such a deal. I don’t know. It’s not possible to know, but the reason so many people are angry at Edward (Teller) and at many other of those conspirators, is that it was considered unconscionable to misuse the security apparatus to try to blacken Robert Oppenheimer’s name, just because of a disagreement on policy.

We now seem to be beyond the Cold War. Do you see any modern-day equivalent to those kinds of challenges of people’s views, because others disagree with them and don’t recognize their right to express it?

Murray Gell-Mann: Right now we don’t have such an acute problem of suppression of ideas as we did then in this country.

Is that because the ideological battle between groups led by the United States and the Soviet Union has receded?

Murray Gell-Mann: Oh, that continued until very recently, and still continues to some extent. But the crisis and hysteria was restricted to a few years in the 1950s.

Do you see any new threats to the freedom of expression in the scientific community?

Murray Gell-Mann: Well yes, sure. For example…

There are the fundamentalists, who believe in the literal interpretation of the Bible in this country, who are trying to make it difficult to explain to students about evolution. And they used to try to get the teaching of evolution suppressed. They have given up on that. Now the push has been in recent years to try to require teachers who explain evolution to explain some sort of nonsense at the same time, and give it equal time, and equal emphasis. Some sort of nonsense based essentially on a literal interpretation of the Bible. I helped to fight against that in the Louisiana creationism case by circulating, among a lot of people, an amicus curiae brief for the Supreme Court. It was signed by virtually all of the American winners of the Swedish prizes in science, and by virtually all of the state academies of science, and may have helped to influence the Justices in their 7-2 decision. I don’t know if it did or not. That two justices could have voted the other way I have found just appalling. Just almost unbelievable, especially when one looks at the arguments they used.

So you do see some threats to freedom of scientific inquiry or expression?

Murray Gell-Mann: Well, fundamentalism is a big threat in many places. There are many different kinds of fundamentalism, all over the world. It seems to be a major threat, perhaps a growing one.

We wanted to ask you about Linus Pauling as well. He was at Caltech for 41 years. He felt compelled to take a stand on a political matter, and to organize other scientists around the issue.