A poem, if it succeeds, brings together the best of your intelligence, the best of your articulation, the best of your emotion. And that is the highest goal of literature.

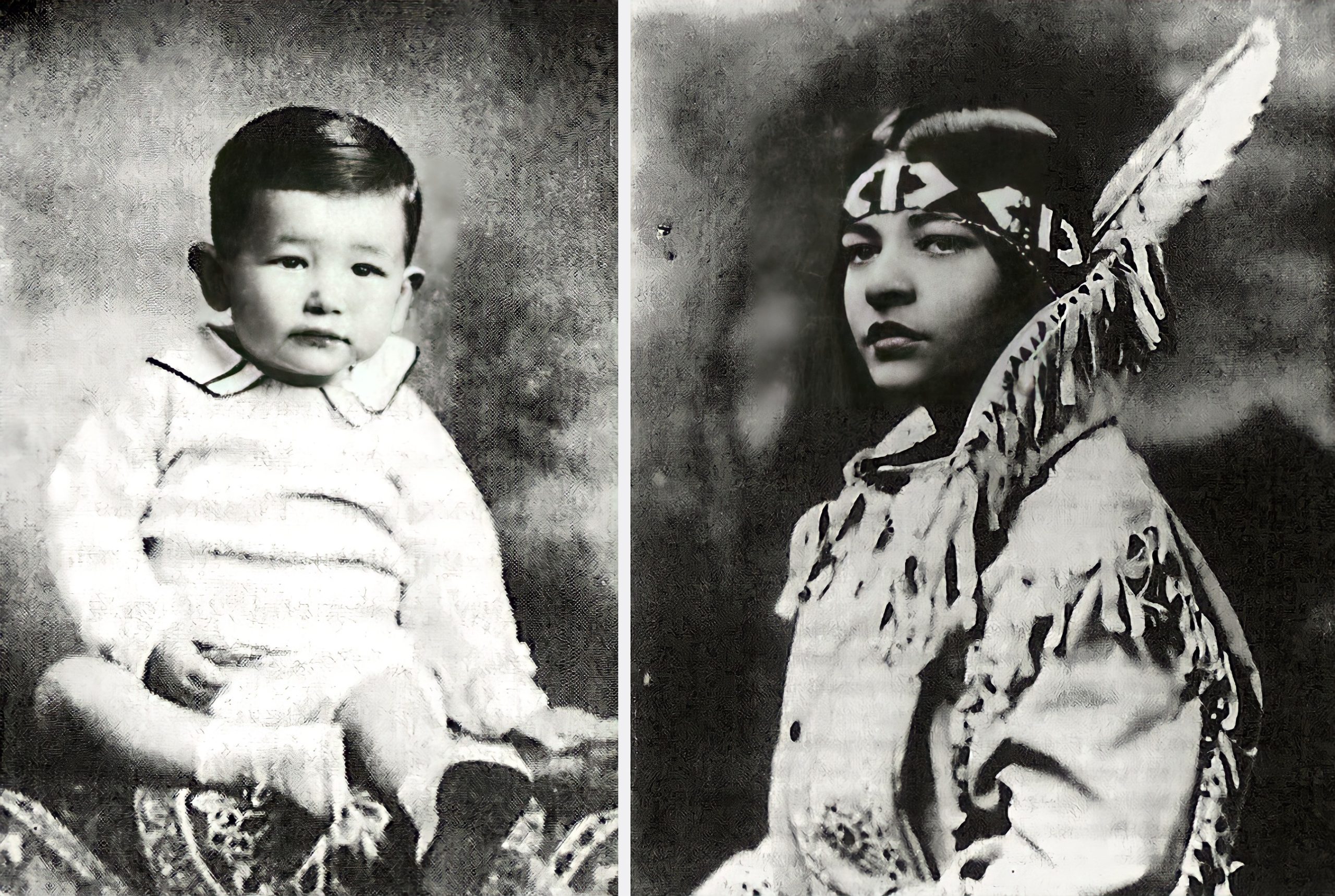

Navarre Scott Momaday was born in Lawton, Oklahoma and spent the first year of his life at his grandparents’ home on the Kiowa Indian reservation, where his father was born and raised. When he was one year old, Scott’s parents moved to Arizona. His father was a painter. His mother, who is of English and Cherokee descent, became an author of children’s books. Both worked as teachers on Indian reservations when Scott was growing up, and the boy was exposed not only to the Kiowa traditions of his father’s family but to the Navajo, Apache and Pueblo Indian cultures of the Southwest. Momaday developed an early interest in literature, especially poetry.

After graduation from the University of New Mexico, and a year of teaching on the Apache reservation at Jicarilla, Momaday won a poetry fellowship to the creative writing program at Stanford University. Under the guidance of poet and critic Yvor Winters, Momaday earned a doctorate in English literature in 1963, and accepted a teaching post at the University of California at Santa Barbara. As his doctoral dissertation, he edited and annotated The Complete Poems of Frederick Goddard Tuckerman. The full edition of works by the 19th century poet Tuckerman was published by Oxford University Press in 1965.

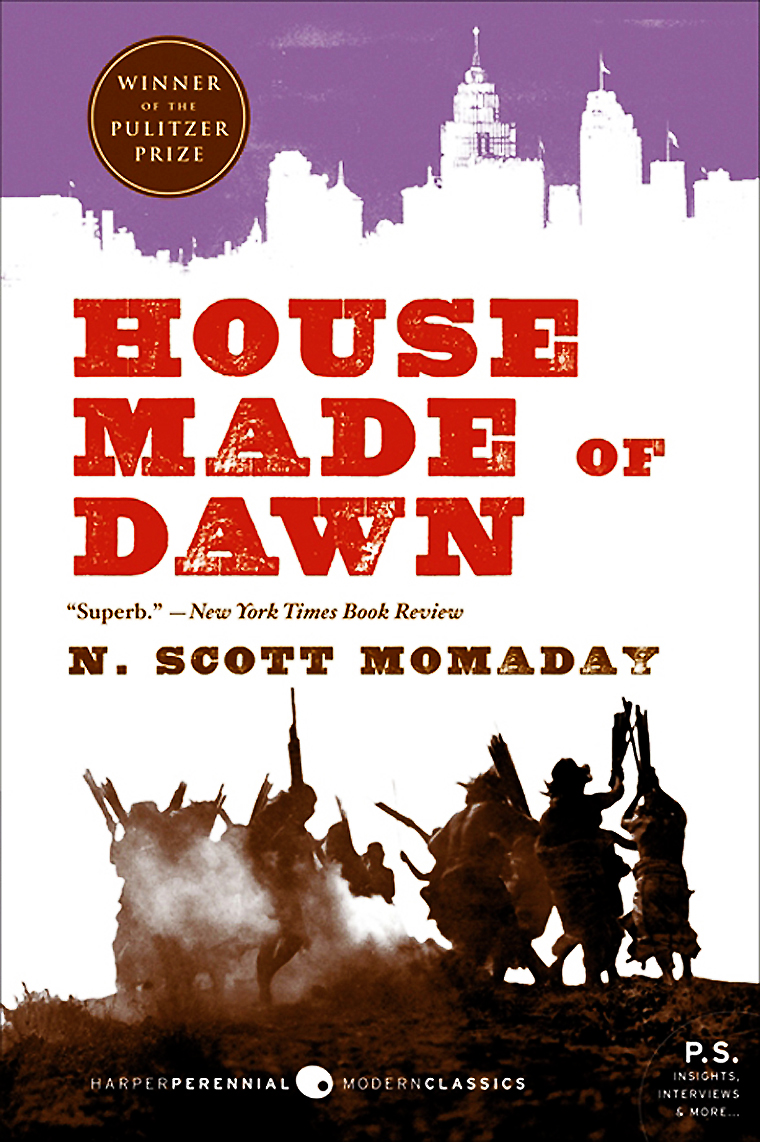

In 1969, his first novel, House Made of Dawn, was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. Momaday moved to the University of California at Berkeley as a professor of English and comparative literature. He designed a graduate program of Indian studies and taught a popular course in American Indian literature and mythology. His long study of the Kiowa oral tradition bore fruit that year in The Way to Rainy Mountain, a collection of Kiowa tales illustrated by his father, Al Momaday. That same year, he was initiated into the Gourd Dance Society, the ancient fraternal organization of the Kiowas.

Momaday’s 1971 essay “The American Land Ethic” drew public attention to the tradition of respect for nature practiced by the native peoples and its significance to modern American society in an era of environmental degradation. Angle of Geese and Other Poems was published in 1974, and a memoir, The Names, in 1976. A second volume of poems, The Gourd Dancer (1976), was partly written while he was lecturing in Moscow, Russia in 1974. During the same period, he took up drawing and painting seriously for the first time in his life. Since then his work has been exhibited throughout the United States. His newer books are frequently illustrated with his own paintings and etchings.

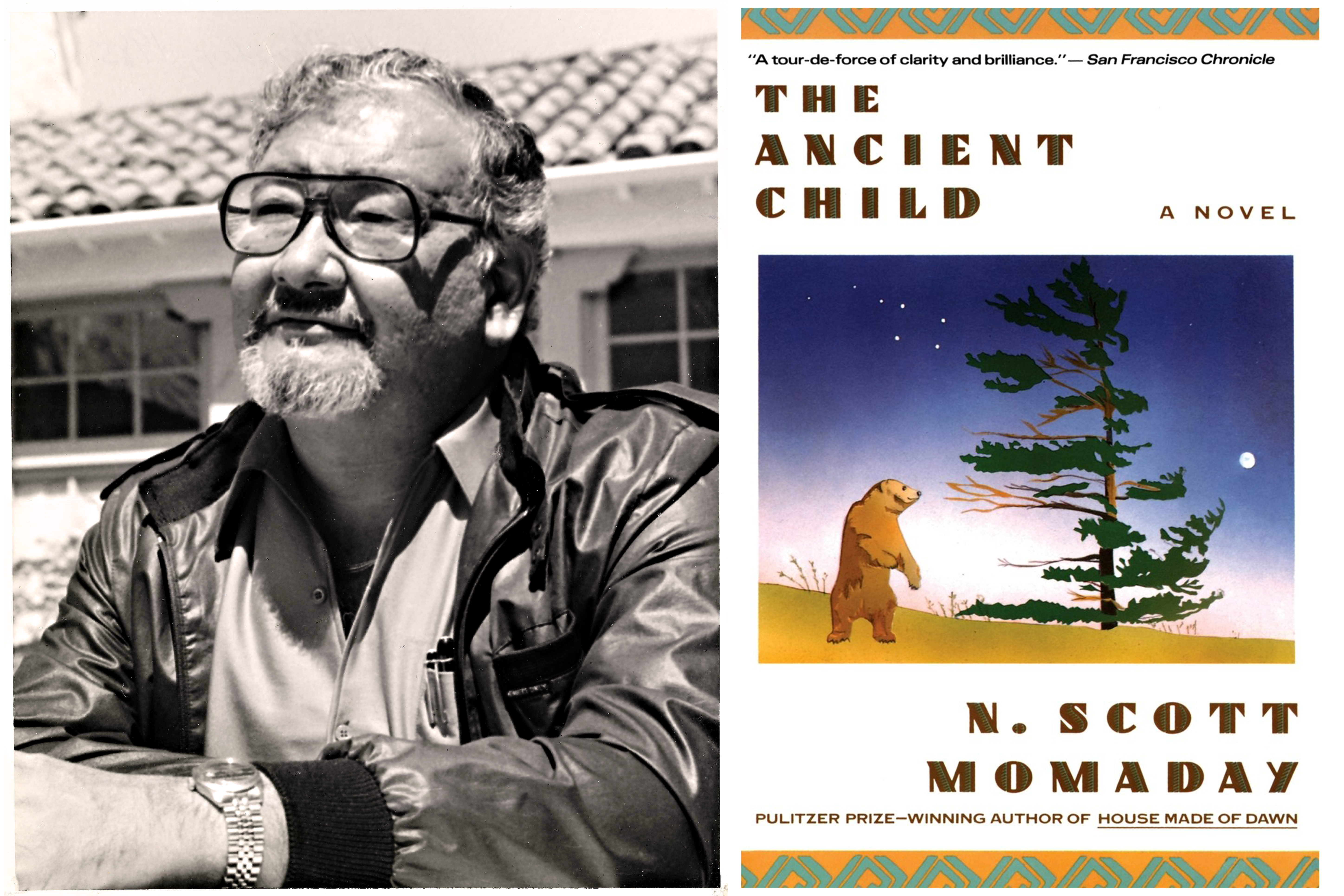

Professor Momaday left Berkeley for Stanford in 1973. Beginning in 1982, he lived in Tucson and taught at the University of Arizona, giving occasional lectures at other schools including Princeton and Columbia. His more recent books include: The Ancient Child (1989), In the Presence of the Sun (1991), Circle of Wonder: A Native American Christmas Story (1993), and The Native Americans: Indian Country (1993). He is also the author of a play, The Indolent Boys, and was featured in the award-winning documentary film Remembered Earth: New Mexico’s High Desert.

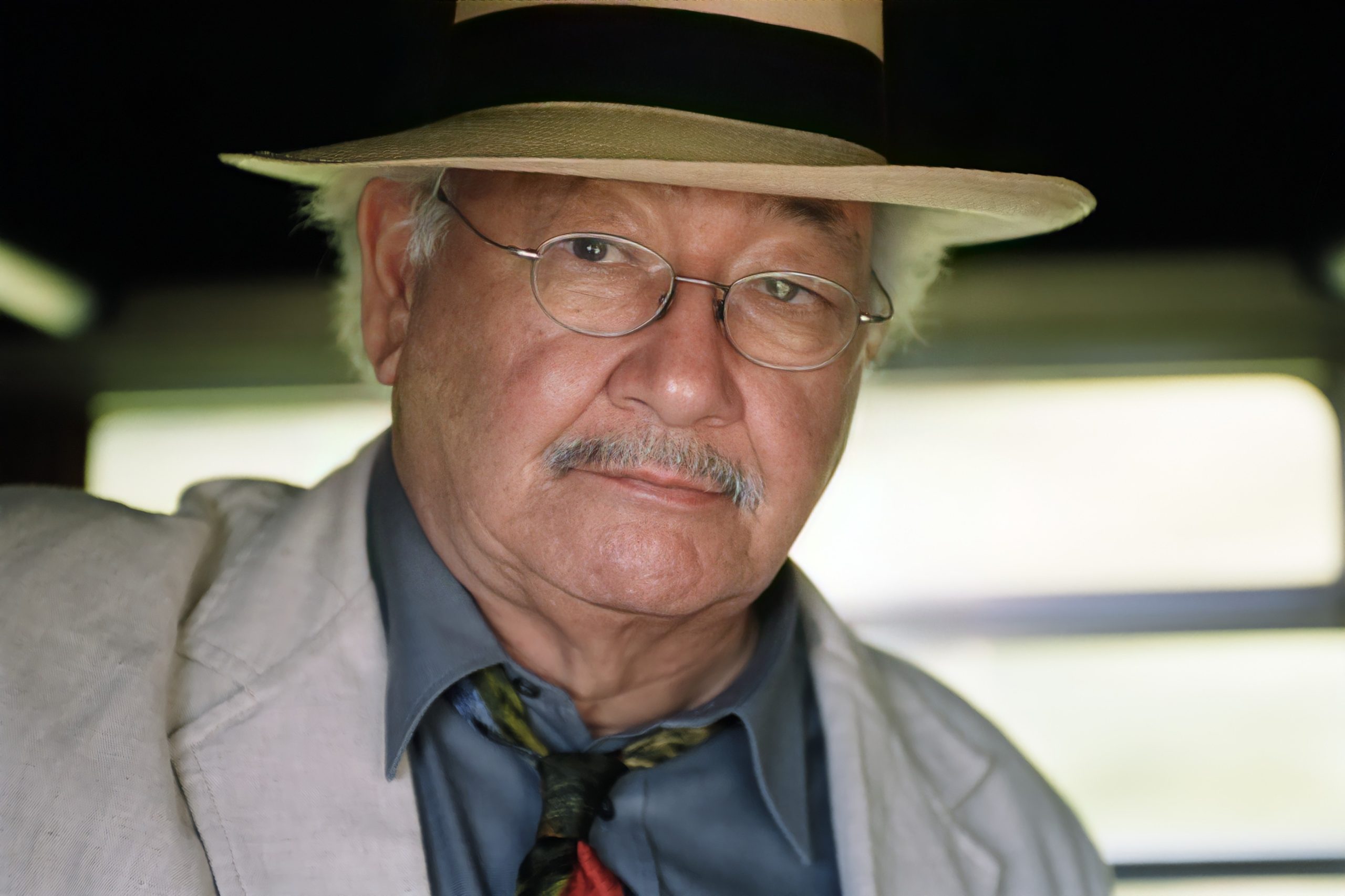

In 2007, President George W. Bush awarded N. Scott Momaday the National Medal of Arts, “for his writings and his work that celebrate and preserve Native American art and oral tradition.” A collection of his verse, Again the Far Morning: New and Selected Poems, was published in 2011.

He now makes his home in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and in recent years has taught courses in creative writing and the Native American oral tradition as a visiting professor at the University of New Mexico, In 2017, he was the subject of a documentary film, N. Scott Momaday: Words from a Bear, produced to air on the PBS television program American Masters.

On January 24, 2024, the literary world mourned the loss of N. Scott Momaday, a monumental figure in Native American literature. Passing away in Santa Fe, New Mexico, Momaday left behind an indelible legacy that transcended his seminal work, House Made of Dawn. He was not only a storyteller but also a fervent preserver of Native American culture and oral traditions. His unique fusion of heritage and contemporary themes earned him widespread acclaim and a devoted following. Momaday’s influence remains deeply etched in American literature, his works continuing to inspire and bridge cultural divides, even after his passing.

“I sometimes think the contemporary white American is more culturally deprived than the Indian.”

The American literary world offers no greater award than the Pulitzer Prize. In 1969 the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction went to House Made of Dawn, a first novel from an unknown author. This was unusual enough; even more surprisingly, to some observers, the winner was a Kiowa Indian who had grown up largely in the reservations and pueblos of the Southwest, far from supposed centers of learning and letters.

As a whole world of readers and critics were soon to learn, there are no limits to N. Scott Momaday’s talents or his vision. As novelist, scholar, painter, printmaker and — above all — poet, Momaday’s work has encompassed a panorama as wide as the western landscapes he celebrates. In Momaday’s work and career, we see an extraordinary fusion of modern Anglo-American literary methods and classical prosody, with Native American traditions of poetry and storytelling.

Through his novels, poems, plays, books of folk tales and memoirs, essays and speeches, he has won international respect, not only for himself, but for the Native traditions that inform his work. At the same time, he has helped to reacquaint the modern world with an ancient understanding of the intimate connection between humankind and the natural world.

Was there any specific event or experience that you can point to that inspired you as a young man, as a boy?

Scott Momaday: Not a specific thing, but an accumulation of things.

I was born at the Kiowa Indian Hospital in Lawton, Oklahoma, then taken to my grandmother’s place. They lived in conditions of dire poverty. I didn’t know it at the time. We didn’t have any electricity or plumbing. I grew up on Indian reservations. I was born during the Depression. My parents were looking for work; they found it with what was then called the Indian Service, the Bureau of Indian Affairs. I lived on the Navajo reservation when I was little, and I lived on two of the Apache reservations, and lived at the Pueblo of Jemez for the longest period of time. So I had a pan-Indian experience before I knew what that term meant. And it turned out to be fortunate, I think, in terms of writing, because I had an unusual experience — and a very rich one — of the southwestern landscape, the Indian world. And that became for me a very important subject.

Were there ideas, values, experiences that you brought from the tribal reservations and your early education that helped you in the world outside the reservation?

Scott Momaday: I might have a hard time cataloguing all of the things that made a difference. I certainly can point to an understanding of the relationship between man and the landscape, for example. I grew up with that, and that’s such an important equation in the Indian world. That has been of great value to me all my life. The Indian world is full of aesthetic values, art. My father was an artist, a painter, and he taught painting to the children at Jemez Pueblo. They exhibited all over the world. They became famous for their art. He once said to me, “You know, Scott, I have never known an Indian child who couldn’t draw.” I believe that. I haven’t either. That seems intrinsic somehow. That’s a real part of the Indian world, this love of symmetry and composition. It’s a great thing. That has been important to me as well. Indian people have a strong sense of humor. It’s not easily understood by other people, but it’s there and I love that. That’s been a part of my life too.

I read that when you were a kid, you wanted to be a cowboy when you grew up.

Scott Momaday: Of course. That comes with the territory. I grew up on the range.

Every boy who grows up in New Mexico, especially southern New Mexico, knows about Billy the Kid. He’s a real presence, an authentic legend. When I was growing up I spent a lot of time with Billy the Kid. We rode the range together. My imagination ran wild with cowboys and Indians. I discovered a book by Will James called Smoky, the story of a cow horse. That was my first great literary experience. I could not put that book down, literally could not put it down. When I had finished it, I read everything I could get my hands on by Will James. Sun Up, all kinds of cowboy stuff. The writing was terrible, but the books were wonderful. It made a great difference in my life. When I was 12 years old, I was, like Alexander, given a horse. There the comparison ends, but that horse meant everything to me. It was one of my great glories. I must have ridden several thousands of miles on the back of that horse in a period of about five years. That was a great time in my life. You know, being the descendent of centaurs, I have always understood the value of a horse, from the time my father began telling me stories. A lot of them were about horses. Horses have always been very important to me.

Who most inspired you as a young man?

Scott Momaday: I was interested in sports when I was a boy, too. I was inspired by Joe Louis. I still think he could beat Muhammad Ali. I had heroes like that when I was growing up. I was inspired by those Will James stories — what they meant, and how they were put together. I think I learned a lot about storytelling, not only from the Kiowa oral tradition, which my father passed on to me, but also in things that I read, including Classic Comics and things like that. They were all important.

What about teachers? Is there a teacher that stands out in your memory as challenging you, or opening up new possibilities for you, inspiring you in some way?

Scott Momaday: Not in the early years, but in college and in graduate school I had several teachers who were very important to me. When I was an undergraduate I took a course in South American history, from a woman named Dorothy Woodward. It was the hardest course I’ve ever taken. She was so demanding! But at the end of the term I realized that I had really learned something, and that was exciting to me. And then, of course, Yvor Winters at Stanford was not only a man who was inspiring, but turned out to be a great friend.

What were you like as a schoolboy? Did you get along with your classmates?

Scott Momaday: Yeah, I’ve always gotten along with classmates. I was in schools that were remarkable in one way or another. For example, many times I was the only person for whom English was a first language. I was in school with a lot of Pueblo kids, and Navajo kids. They spoke a kind of broken English, and I didn’t. I suppose that was to my advantage in some ways, but a disadvantage in others.

I wasn’t really challenged when I was in the early grades. That’s pretty much true all up through high school. I think I was ill-prepared for college. I hadn’t had a lot of really valuable training. So it came as a kind of shock to me. But I managed to do what I was supposed to do. I wasn’t a great student. I didn’t care that much about grades until I got into graduate school. Then I thought, the time has come to really make an effort now, and so I did. More important, by that time I had put myself in a position where I could hold my own.

All the way up to your senior year in high school, you were in reservation schools.

Scott Momaday: Pretty much. I was in all kinds of different schools, some on the reservation, some off. I went to four different high schools, and for two of those years I rode a bus 28 miles one way to school. I boarded with an old German couple in Albuquerque in my sophomore year, and then I went to military school for my senior year. I had run out of schools, and my parents and I thought that if I really wanted to go to college, I had better go to a school that could give me some college preparation. So I selected a military academy in Virginia, and I went there my senior year.

What possessed you to pick a military academy in Virginia?

Scott Momaday: I don’t really know. It was a romantic kind of thing. My mother was born in Kentucky and some of her ancestors had come from Virginia. She was always very interested in that part of the world, and in that part of her ancestral experience. So I had an interest in the Old South, in the Old Dominion. So when I got these catalogues, that’s where I gravitated, to the Shenandoah Valley.

How did it affect you, moving from one world to another, back and forth between the Indian world of the reservation, and the one outside, especially at so young an age?

Scott Momaday: I think that’s the answer. It happened when I was young, and kids take things like that for granted. If it had happened to me at a later time in my life I probably would have been terrified. But going back and forth between the Indian world and the white man’s world was a piece of cake at the time. It’s like learning a language. Language is child’s play, and the kind of experience I had was child’s play.

Did you always have this sense of Indianness wherever you went?

Scott Momaday: As I look back on it, because I was very frequently among Indians who were not of my tribe, and we couldn’t converse, we didn’t have the same language. But I always had a sense of being one of them because I’m Indian. They had the same sense of me. We got along well because we were all Indians together. That’s something that I think is of importance, and something that happened in my lifetime. When I was little, people didn’t think of themselves as Indians. They thought of themselves as Kiowas, or Comanches, or Crees, or whatever. But in the last 50 years or so, the tribal distinctions have broken down. But the sense of Indianness has remained as strong as ever, and maybe it has become stronger. And I can’t account for that except to say that the outside world has made incursions, and the Indians have left the reservation, and so there’s been a much greater kind of communication back and forth. And now we have things like pow-wows, which are extremely important in bringing young people — especially — together from every kind of different tribe and language. And they trade words, and dance steps, and music, and so on. And so, they bond and become a people, instead of the members of a lot of different tribes, and I think that’s healthy.

There’s no question that this sense of Indian identity has enriched and informed your life and your work.

Scott Momaday: That’s very true. One of the things that amazes me is that I think the Indian is more secure than he was a half-century ago. He has a much better idea of himself and of the contribution that he can make. He’s only two percent of the population, but has an influence much greater than that would indicate. I am lucky, because I do have a sense of my Indian heritage. That’s very firmly fixed in my imagination and in my mind. I am more fortunate than most other people.

When I published The Way to Rainy Mountain, someone who was writing a review — or interviewing me — said to me, “You know, you’re very lucky to know who you are, with respect to your grandparents, your great-grandparents, five generations back. You know about that. I don’t know that about myself, or my people.” And that came as a surprise to me, because I hadn’t thought about it, you know. And I had taken it for granted. But I sometimes think that the contemporary white American is more culturally deprived than the Indian, in that sense. Because very few people know about their ancestry, going back even a generation. I’m always appalled by students who — you know, I say, “Well look, you’ve got an oral tradition. You’ve got a family oral tradition, if nothing else. Tell me about your grandparents.” And sometimes they just don’t know about their grandparents, and I find that very sad, and alarming, but it’s true. It’s true.

It’s possible to have both. It’s possible to have this identity, this cultural inheritance, whether Indian, or black, or Polish, whatever it is, and still be a part of this country.

Scott Momaday: Yeah, I think that’s how it works. This country is made up of people who have both things, or the possibility of both things. I don’t think people appreciate that enough. We need to talk to them about that. Spend some time thinking about who you are and how you became who you are. It’s important. We’re moving at such a pace that very few of us stop to reflect upon it. Reflection is important.

What does the American Dream mean to you?

Scott Momaday: It means a great deal actually, and the reason it does has something to do with my being a Native American. I belong to a race of people, a society, that has been oppressed. We, the Indians, have had a hard time, for a long time. We have had to endure a great deal, but the dream means as much to us as it does to anyone. You’ll never find a greater patriot than an American Indian. It’s not by accident that I, a member of the Gourd Dance Society, go to Oklahoma to dance on the Fourth of July, you know. It is not an accident that the greatest honor that can come to an American Indian in my generation is to serve in the armed forces. And the veterans who have given their lives are greatly honored by the Native people. So, the dream is very important to me, and it is, I think, to Native Americans in general.

Could you define a turning point, or a defining moment, a big break in your career?

Scott Momaday: I suppose the fellowship I was awarded to at Stanford. I could say that was my first big break. It was an opportunity that I was not expecting, and it turned out to mean a great deal to me.

What do you think Stanford saw in you?

Scott Momaday: I don’t think Stanford saw anything in me particularly, but Yvor Winters did. He was the man who chose the poets for the fellowship. I didn’t know him at the time, but when I applied, I submitted several poems, and the outline for a collection of poems.

He saw in it something that he wanted to encourage, so he wrote to me and said, “You’ve been awarded the poetry fellowship.” There was only one that year, this was 1959. He became my advisor. That was an important moment in my life, because he was extremely knowledgeable about poetry. I was very much interested in poetry at the time, and he was in a position to take me over and help me learn poetic forms and so on.

Why was that a turning point for you?

Scott Momaday: I had not wanted to go on with my schooling. I had graduated from the University of New Mexico with a BA. I had taken a job teaching at the Dulce School on the Jicarilla Reservation. I spent a year there and I loved it. Wonderful setting, great people, the kids were wonderful. I was teaching seventh graders, up through eleventh or twelfth graders. And I was a bachelor earning the princely sum of $4,000 a year. Nothing to spend it on, except steaks down at the trading post. I’d go buy the best piece of meat you’ve ever seen and bring it home and feast on it. I won the fellowship to Stanford. And I thought, “Hey, I’ll go to Stanford. I’ll live off the fat of the land there for a year. I’ll learn something about writing. It’s a great opportunity, but then I’ll come back here.” I took a year’s leave of absence. I meant to be gone for a year. I ended up staying 20 years in California because Yvor Winters talked me into going through the mill there. So I took the bachelors and then stayed in and took the doctorate. By that time I was overqualified for Dulce, so I got into the business of college teaching.

Is it possible to articulate what Yvor Winters saw in the poems that you submitted?

Scott Momaday: I was writing in a kind of Native voice. I had already become interested in the Indian oral tradition and I wanted to incorporate elements of that tradition into my work. I think he thought that was exciting. It had interesting possibilities and he responded very favorably to it.

Of all the forms you’ve written in, why is poetry the most important to you?

Scott Momaday: Poetry, it seems to me, and I’m pretty sure I’m right about this, is the crown of literature. To write a great poem is to do as much as you can do in literature. Everything has to be very precise. The poem has to be informed with motive and emotion. You’re bringing everything that literature is based upon to bear, when you write a poem. I think of myself as a poet. I’d rather be a poet than a novelist, or some other sort of writer. I think I’m more recognized as a novelist, simply because I won a prize. But I write poetry consistently, though slowly. And it seems to me the thing that I want to do best.

I think it’s the highest of the literary arts. A poem, if it succeeds — if it is what it ought to be — brings together the best of your intelligence, the best of your articulation, the best of your emotion. And that’s the highest goal of literature, I suppose. I would rather be a poet than a novelist, because I think it’s on a slightly higher plane. You know, poets are the people who really are the most insightful among us. They stand in the best position to enlighten us, and encourage, and inspire us. What better thing could you be than a poet? That’s how I think of it.