You were born into a very particular society. Can you tell us a little about your childhood? Where were you born?

Nadine Gordimer: I was born in a little gold mining town called Springs. There was no spring around, I don’t know why it was called that, and I spent my school days there. I grew up there.

Did you have any siblings?

Nadine Gordimer: Yes, I had one sister. My mother went to a dancing exhibition of some friend of hers who was a dancing teacher. There was a little girl there who danced beautifully and who was called Nadine. She was pregnant and she decided that if she had a daughter again — because my older sister was already there — she would call her Nadine. So that’s how I got my name.

Could you tell us about your parents, Isidore and Nan?

Nadine Gordimer: Well, Nan was my mother and she came from England as a child with her parents. My father came from Latvia, from some tiny little village somewhere. So they came from very different backgrounds and they were very different people.

So your father was from Latvia and your mother was from London. Was religion a big part of your childhood?

Nadine Gordimer: No. They were both Jews, but my mother was an agnostic and my sister and I didn’t have any education as Jewish children. My father used to go to synagogue on occasion, fasting and days like that, and to honor his parents and the anniversary of their death, but that was all. I went to the Convent of Our Lady of Mercy, a Catholic convent school, and nobody tried to convert me to anything.

Did you find that a difficult experience, going to an all-white all-girls Catholic school?

Nadine Gordimer: Well, Catholic had nothing to do with it. Perhaps if I’d had a Jewish education, it would have meant something to me. The fact that it was all white…

You must remember that I was born into a society where there was no question of “mixed” pupils at schools. But I early on began to realize how artificial our life was, and indeed to think, “Well, I go to this school…” of course it was all all-girls as well — and on Saturday, great time, pocket money and after the movies — no black could go to see a film. And I just as a small child presumed they were not interested and didn’t like it, it was not for them. But the most important thing was that I was made, by my mother, a member of the children’s library when I was six years old, and became a great reader, and very soon left the children’s department and took what I liked from the adults’. And I realized later in my life, this was my education, really, because I became a great reader and I had the library. We were not rich and nobody could have bought enough books to satisfy my desire to read. If I had been a black little girl, I couldn’t have used that library. It was closed to black people, a municipal library. So there you are.

Who did you find inspiring as a young person? Was your mother an inspiration to you?

Nadine Gordimer: I don’t like this word “inspire.” I think you have to find what wakes up what is latent in you. You may admire someone else, but to inspire suggests that you want to emulate them or be like them. You cannot be like anybody else, not even the great writer or the great actress that you happen to admire. I think that, again, I come back to books. My desire to understand life, to explore it, came through literature, through reading. And I always tell aspiring young writers, “Forget about creative writing classes.” You can’t teach people to write poetry or novels or short stories. You can teach them to be good journalists, that’s another thing. But you cannot teach them literature this way. And the only way you can teach yourself is to read, read, read. Not in order to emulate or copy what you read, but to become self-critical, to look then at your own little efforts and think, “My God! Look what this one and that one can do with a word that I haven’t even touched yet.”

Can a young writer without much life experience be a good writer? What makes a good writer?

Nadine Gordimer: It’s a combination of life experience, what’s happening around you, the kind of society that contains you, and your development in yourself, your emotions, your relations with other people.

Going back to your school years, were you a good student?

Nadine Gordimer: No, not particularly. The teaching wasn’t very inspiring.

Do you wish that you had a better education as a young person?

Nadine Gordimer: I wish only one thing, and that is that I had learned an African language. We have 11 languages in South Africa and of course we were taught, as whites, only English and Afrikaans, but not an African language. But I reproach myself now, because why didn’t I learn one when I grew up? But by then of course, any excuse. I was concentrating, as a writer must, on the language that he or she is writing in. But I still, that is my great regret that I did not learn an African language, and that I did not see to it that I learned when I was adult.

In that first municipal library, what were some of the books that you just couldn’t get enough of?

Nadine Gordimer: Well, it was amazing, because in the children’s library they were obvious. For my generation, it was Hugh Lofting’s Dr. Doolittle. I did pass it on to my children and their children.

But, as soon as I moved into the adult library — and my mother was a friend of the librarian, who was a woman, so nobody stopped me — and then I read an amazing variety of things. Some history, some translations from Greek, a bit of Sophocles and so on. And then my parents had friends whom they used to go every weekend to play cards there — and I went along. And then I would be left alone — and the man, who was a lawyer — in his study, and he had quite a good library. And it included the — of course banned — Lady Chatterley’s Lover. But I read Lady Chatterley’s Lover when I was about 12 years old. And there were many other books of that nature.

Are there any other titles that come to mind?

Nadine Gordimer: Well of course I read Dickens, and very soon I discovered Tolstoy, War and Peace.

At age 12?

Nadine Gordimer: No, bit older, about 13 or 14. And so it went on. Then E.M. Forster, Passage to India, and of course some poetry. Though at school we’d had Wordsworth stuffed down our necks, but then I moved on obviously to contemporary poets of my time.

When you were a little girl, did you put on shows or do impersonations for family and friends?

Nadine Gordimer: No. I think I used to mimic other people rather nastily, my mother’s friends who came to — I don’t know whether it was a book club or what it was. I would listen carefully and then I could reproduce for other people’s amusement, which wasn’t a very nice thing to do. But I think quite a good training for a writer, because as a writer you have to project yourself and indeed you have to use the vocabulary and the turn of phrase of characters who are very different from you. So this was a kind of training of this projection.

So this observation was part of your training?

Nadine Gordimer: I think if you ask what the qualities of a writer are, you have to be born extremely observant. That is really the beginning of it. Because as Graham Greene notably said — when people asked, “Are your characters based on people?” — the answer is no, if you’re a real writer, unless you choose a particular individual. You choose Napoleon and then you write a novel about his love life, you know, then you recreate it. But in general, what Greene said, and that I think is absolutely true and I found in my own life, he said, “You are sitting in a bus or in a queue, you are waiting to go in at the dentist and there are people there.” First of all, you have to have big ears. You eavesdrop. You catch a word here and there. You see that there’s a quarrel brewing perhaps, in the restaurant, and a love affair brewing somewhere else, and a case where one dominates another. You see these people and you read their body language and you create alternative lives for them.

Your first stories were published in the children’s section of the Sunday paper. How did that come about?

Nadine Gordimer: Obviously, my parents got the Sunday paper and there was this large spread that was the children’s section. And then they invited children to send things in. And I was already, from the age of nine, scribbling away. So I wrote a story which had something to do with the rainbow and what was found at the end of the rainbow and sent it in and it was published. But my first adult story was published when I was 15, in a liberal journal that was on at the time. And of course they didn’t know that this was written by a child. And what a great moment when, indeed it was November that year when the paper arrived, and there was my story printed and I was even paid for it.

That must have been a really exciting moment.

Nadine Gordimer: It was a great moment, yes.

Were your parents supportive of your ambitions?

Nadine Gordimer: Well, fortunately for me, I think I could have been ruined by being made a child prodigy. It was just a moment, you know, Nadine amusing herself. At that time, until I was 11, I was a passionate dancer, at dancing class. Of course I had the right build for it, being very small and light, and my ambition was to be a dancer and I wasn’t bad. But fortunately for me, I changed ambitions or I would have been really over and done with long ago now.

What happened when you were 11? Why did you stop dancing? Was it your health?

Nadine Gordimer: I had some very common condition that I’ve discovered since, to do with the thyroid gland, which happens sometimes when you’re on the brink of adolescence and all your glands are starting to throb and come up. For reasons that I shouldn’t go into, my mother’s marriage and so on, she clung very much to her children, and she made a tremendous thing of this, and the first thing I was made to give up was the dancing, which was a great deprivation for me.

So you didn’t want to give up dancing?

Nadine Gordimer: Well, of course not, but she said I had a bad heart. I’ve lived now to this great old age with that same old heart, so I’m afraid it was a mistaken diagnosis.

What about your middle years at school? Was your health a factor there as well?

Nadine Gordimer: She took me out of school, and then I had to be taken every day to a retired school teacher. So all on my own I learned my lessons, which again was a great deprivation, without my friends. Anyway, I’ve survived.

Your family home was raided by the police when you were a teenager. Do you recall that experience? Were you home at the time?

Nadine Gordimer: That was the experience that led to one of my very first stories, yes, the second or third adult story. And not only that, it led to my understanding of how we were living as privileged whites, even though we were not rich, compared with what the real situation was in the country. Because indeed, in the middle of the night there was a row going on in our yard of our house, and my parents and I got up. My sister had already left home. I think she was married or something, or she was at university. She became a teacher. And we went out and there was the woman who worked for us, and who — you know so very well the old American South situation, you know. Here was “White Mama” and “Black Mama.” So Black Mama, they had rifled her room; they had turned her mattress over. They were looking for illegally brewed beer, and of course there was a lot of illegal brewing around. I don’t know whether — Letty her name was — whether Letty brewed. Why should she not, on the side? But fortunately, it was nothing there that night. But everything was thrown out all over the place, even outside the room into the yard. And we stood there, my parents and I, and the police were there, black policemen under the direction of a white policeman doing all this, and my parents didn’t say to the police, “Where is your warrant to come into the house and do this?” I mean, they just walked into the property because they were doing the right thing. They were trying to stop black people from brewing. So I began to think about that afterwards, and then to look at many other things in our life.

World War II began when you were in your teens. How do you recall learning about the war? How did you receive news about the war?

Nadine Gordimer: On the radio, of course. We didn’t have television. Radio, newspapers, and of course, letters and telephone calls to people overseas. And all of us, we girls, had our boyfriends up in the Middle East writing to us. Of course they couldn’t write about what they were experiencing, but we saw in the papers that there was this battle and that battle. And in their letters, even though they were censored, they could say, “I’ve just come back from blah, blah, blah…” whatever it was.

How did you become interested in writing for publication? Was there a particular moment that first piqued your interest in writing professionally?

Nadine Gordimer: No, no, no. That is a sort of decision people make when they go for a regular career, not one like writing. How should I put it? I always compare a writer with an opera singer. If you’re going to be an opera singer, you are born with certain vocal chords, which I imagine you don’t have and I certainly don’t have. Unless you have that, you can go to all the voice training in the world, you’re not going to land up at La Scala. But if you have it, then you can develop it. Now if you’re going to be a writer, we have to go back to what I said before, you are born with certain characteristics. First of all, tremendous sense of observation, as I say, and a great curiosity about life. You’re not prepared to take all the answers. You know, “If you’re a good girl, you’ll go to heaven,” and “God is looking after you,” and this, that and the other, and “You must listen to your teacher,” and so on and so forth. So an independent mind is like having these special chords if you’re going to be an opera singer. That’s really the beginning of it.

Did you already think that you would make a living by your writing, when you had that first story published at 15?

Nadine Gordimer: How could I? I had no idea how I was going to make a living. Of course it was presumed in the circles in which I lived that when you finished school you would be a typist, or indeed, if I had gone on dancing, I might have been a dancing teacher of children. And of course you got married and then you didn’t work. That was the end of your working career. There were very few women doctors, and I didn’t know a single woman lawyer where I lived. This all was not in our milieu.

What about university, did your parents encourage you?

Nadine Gordimer: No, not at all. I decided much later when I was about 19, and when I was already publishing here and there, and living at home and eating food provided by my father and so on, that I wanted to go to university. So I went to the University of Witwatersrand as an occasional student for one year, no degree, and then left. And of course it was interesting because it was just after the war, and there was this big division. I was like the people who had come back from the war, the soldiers, who then were, you know, adult, and in my case I found that I had read far more than either they had — because they hadn’t had the opportunity — and also the younger ones who’d just come from school. So what they recommended reading, I had already done for my own pleasure and my own enlightenment. But what I did learn that year there was — indeed through one good lecturer — was to become, as I say, very self-critical. Not just to think that whatever I had written was just what I wanted to say, but to see how it could be critical that it didn’t. I then began to see where I was failing.

Looking back, did you ever know why your parents didn’t encourage you to go to university?

Nadine Gordimer: No, no, I haven’t thought about it. I don’t dwell on my childhood. Too many people live on their crummy childhood. You must outgrow it.

Do you have other memories of witnessing racism, of seeing something you knew was wrong?

Nadine Gordimer: No. I’ve told you about that time of the raid on Letty, our housemaid or whatever she was. I know what we called it at the time… I thought “servant” was the word.

Your first contacts with black South Africans were as servants. When did you form your first relationships with black South Africans as comrades, fellow writers, fellow artists?

Nadine Gordimer: I would say it began through the common ground of young writers, artists, actors. When I was… that year I talked about at university. The University of Witwatersrand was a white university, but there were certain occasions when there was a subject that was not taught at the black university, and here and there a black student would be accepted, usually a post-graduate. Now through somebody there — and there were people connected who came back from the war, who were very against the result of what they had fought for, freedom, and then you come back to another fascist country. You’ve just defeated one, now you come back to one which is your own. And one of my first friends, black friends, was the wonderful writer, Es’kia Mphahlele — Zeke, as he was known then. Zeke and I met, I don’t quite remember how, and we were both young writers, just wanting to teach ourselves how to write, and we started to exchange. He’d show me his story and I’d show him mine. Of course, his position was very different from mine, because he was black, and it was then that I began, along with others, to — I won’t say “defy,” that sounds… to “ignore,” which is a very strong form of defiance, the edict that black and white mustn’t mix. So mixed parties, going to a shebeen together and so on, that really started for me then. And then I met many others, and especially people also in the theater. A wonderful writer called Todd Matshikiza and a number of others whose names probably wouldn’t mean anything to you.

We’d like to ask about your memories of Sophiatown. Do you remember the day of the relocation?

Nadine Gordimer: Oh, you mean when they took people out of Sophiatown? Oh, I remember the day, yes. I wasn’t there, but I had friends who lost their homes, my black friends. So it was something that one could never really forget. And of course then we realized, because it was right next door, so to speak, that it was happening all over, that people were having their houses bulldozed.

Could you tell us about Bettie du Toit? She was your friend, wasn’t she?

Nadine Gordimer: Yes, a great friend. The closest woman friend I’ve ever had, quite wonderful. From her too, I think I received a political education. She was of solid Afrikaans stock, because that’s a Huguenot name, “du Toit.” But here we call it “Du-toy,” because it got naturally, I don’t know, Afrikanerized. Bettie was a member of the Communist Party. She had been illegally married — I mean married somewhere else and came back to live here — to an Indian of the prominent Cachalia family. She worked in trade unions. She worked with Albie’s father, Solly Sachs, and the garment workers union, and this one and that one. Anyway, this was a world unknown to me with my little sheltered life. She was, of course, also white, and she had been totally disowned by all her family because she was a traitor. We became great friends, both my husband and I, really close to her because I happened to meet her as a young divorced woman. My first marriage was a failure.

I met Bettie du Toit and my future husband then, Reinhold Cassirer, on the same day in somebody’s house, yes. And the three of us were very great friends, and both Reinhold and I felt she was our guru in many ways, because she was right in the thick of the whole thing. Now of course, the time came when she was detained, she was in detention. Her family had abandoned her. All her comrades in the movement, in the ANC and the South African Communist Party, dare not come forward and say, “We want to visit her.” You were supposed to have family visits only. Anyway, it was no great courage on my part, it was just the obvious thing to do. I went to the police, you had to go, and said I’m her sister and I wanted to see her. So they said, “But you’ve got a different name.” I said, “Of course I’m married now.” So I got permission to see her, and that meant I could go to the women’s section of the Old Fort, which is now the famous Constitution Hill complex, part of that. Albie would have talked about it. So I saw the inside of a prison for the first time. And to see your friend there is quite extraordinary, all part of your education if you lived here. On a visit then, I would be sitting here, there would a heavy grill in front of me. She’d be brought in and she’d sit on the other side, and then we would talk through this with two warders looking at their watches and so on. But I think it was very fortunate for me that I had this experience. It made me understand the realities of where we were living. And so my involvement with and adherence to the liberation movement started.

Why was she detained?

Nadine Gordimer: She was detained for all her activities, for her activities within the ANC, the meetings. The Umkhonto (armed wing of the ANC) hadn’t been formed yet, but there were many other things. And as I said, she used her trade union experience as well to speak against the apartheid regime and so on.

Could you take us up to March 1960 and the Sharpeville Massacre? What do you remember?

Nadine Gordimer: Everything. We didn’t have TV, but we did have the newspapers and we did have the radio, with some censorship, but still. And of course, one had friends. I certainly had friends among journalists and among political activists who were back and forth. So one was very well informed. But it was a remarkable thing. It was tragic, the killing of that boy. But the courage, it was the children who really gave the impetus to their elders to take the struggle further. As Chief Luthuli said, who was in Congress, very much a leader until the youth group with Nelson and others took over. He said once in a speech, I’ve never forgotten it, “We are tired of knocking on the back door.” So this was the end of knocking on the back door.

In the 1960s, the liberation movement in South Africa became an armed struggle. There were bombings and assassinations. Was there ever a time when you considered arming yourself?

Nadine Gordimer: No, no, no, never. We’re talking about the height of apartheid, when indeed I gave evidence for the defense in a big treason trial. My great friend, the wonderful, great lawyer, George Bizos, Nelson Mandela’s lawyer, said to me, “Look, please, when you get out of your car, have a look,” because of what happened to Albie Sachs. Albie of course was a great figure in the liberation, which I was not. But now, once having given this kind of evidence in a big court case, George thought that there might be some danger. And I thought, “Good God, how ridiculous. Who’s going to?” That was really the only… and then there were other times. You know, I feel my own contribution, it was never enough, but my husband, Reinhold Cassirer and I, we hid people. We did all sorts of things.

You mentioned Nelson Mandela. Did you meet him before his arrest in 1962?

Nadine Gordimer: Oh, yes indeed. I was introduced to him, my great good fortune, by the English journalist, editor of Drum, Anthony Sampson, who was introduced to my husband and me and who became an intimate of the house, a great friend. He was reporting that first trial in the Drill Hall here, and he took me along, and in the recess I met Nelson Mandela, and so after that I was fortunate enough indeed to get to know him.

Did you do any writing for Drum?

Nadine Gordimer: I never wrote anything for Drum. No. We were friends. Drum was indeed, quite rightly, to encourage writing among urban blacks. It would have been presumptuous of me to write for Drum.

Do you remember that first meeting with Mandela? What did you talk about?

Nadine Gordimer: Oh, how do I remember! Well, we talked politics, of course. What else would we talk about?

How soon did you see him after his release from prison in 1990?

Nadine Gordimer: Since his release? Well, I saw him very soon, indeed. I was there the day when he came out, saw him come out of the prison, yes. I was with Anthony Sampson, and then I saw him alone after that. When he was in prison, indeed, among the people he asked to see, he asked to see me. And I applied and I was refused. They wouldn’t let me see him on the island. But I was one among a number of people who were refused. Indeed, oddly enough, somebody had smuggled in Burger’s Daughter, and he read Burger’s Daughter and then he asked to see me. So I was absolutely delighted and was ready to hop on a plane and go to Cape Town and go to the island but, as I say, I had to apply and the answer was no.

Were you given an explanation?

Nadine Gordimer: No. You weren’t entitled to one.

So when he was released, you saw him right there at the gate.

Nadine Gordimer: Yes. And when the negotiations were going on, he and some other comrades, it was useful for them to have a house where they could meet quietly, so they came here.

They came here, to this house?

Nadine Gordimer: Yes.

Did you really just talk politics with Mandela?

Nadine Gordimer: Oh, we talked all sorts of things. He’s a very lovely man and Nelson has many interests.

Can you tell me some of the topics that you talked about?

Nadine Gordimer: Oh well, he talked about his childhood and youth. But we talked mostly about, you know, politics and what was going on, yes.

Have you ever had a real disappointment in your career? Has there been an event or a milestone that you found disappointing?

Nadine Gordimer: Frankly, no, because first of all I would never think of milestones. I have been surprised that this book got more attention and has lived longer than that. And I haven’t always agreed with it. I thought, “Now why is that one favored?” For instance, a book of mine called July’s People never dies and is taught in schools and so on. But I suppose it has certain reasons, because it was the only novel I’ve written which had something frankly prophetic in it. It was written at a time when we were like the swine, waiting to throw ourselves over the precipice (Luke, 8:33) into a terrible civil war. And it could so easily have happened. So what is told in a personal way, in a family, in microcosm, what happens in that book seems to catch people so that they would think, I’m now presuming, “Oh my God, this so very nearly happened to us.” So it’s taught in schools all the time, which amazes me too. Or perhaps it’s good, because it reminds them what they’ve come from, what their parents lived in.

Why did it surprise you that July’s People seems to have legs, as it does?

Nadine Gordimer: Well, I would have thought Burger’s Daughter or The Conservationist. But you see The Conservationist, I haven’t got a crystal ball, but the question of land has come up. So that now-old book was about land. Six feet, the grave, was all that a black man had. But that goes way back to my second book of stories, which was called Six Feet of the Country, and also was the matter of a burial of a black man.

Was there a time in your career when you felt you could say you were a success as a writer?

Nadine Gordimer: I can’t understand why anyone should look at themselves in this way. Then I suppose I should have said the climax of it would be the Nobel Prize. When I think of the Nobel Prize, it was very wonderful indeed. But when I think of what we talked about before, that first story in an adult paper, arising out of the raid on the house. I was 15 years old, I pick up the paper… That was a tremendous thrill. When you grow older and you’re fortunate enough to have good experiences with your work, it wouldn’t have quite the impact that had, when I was 15.

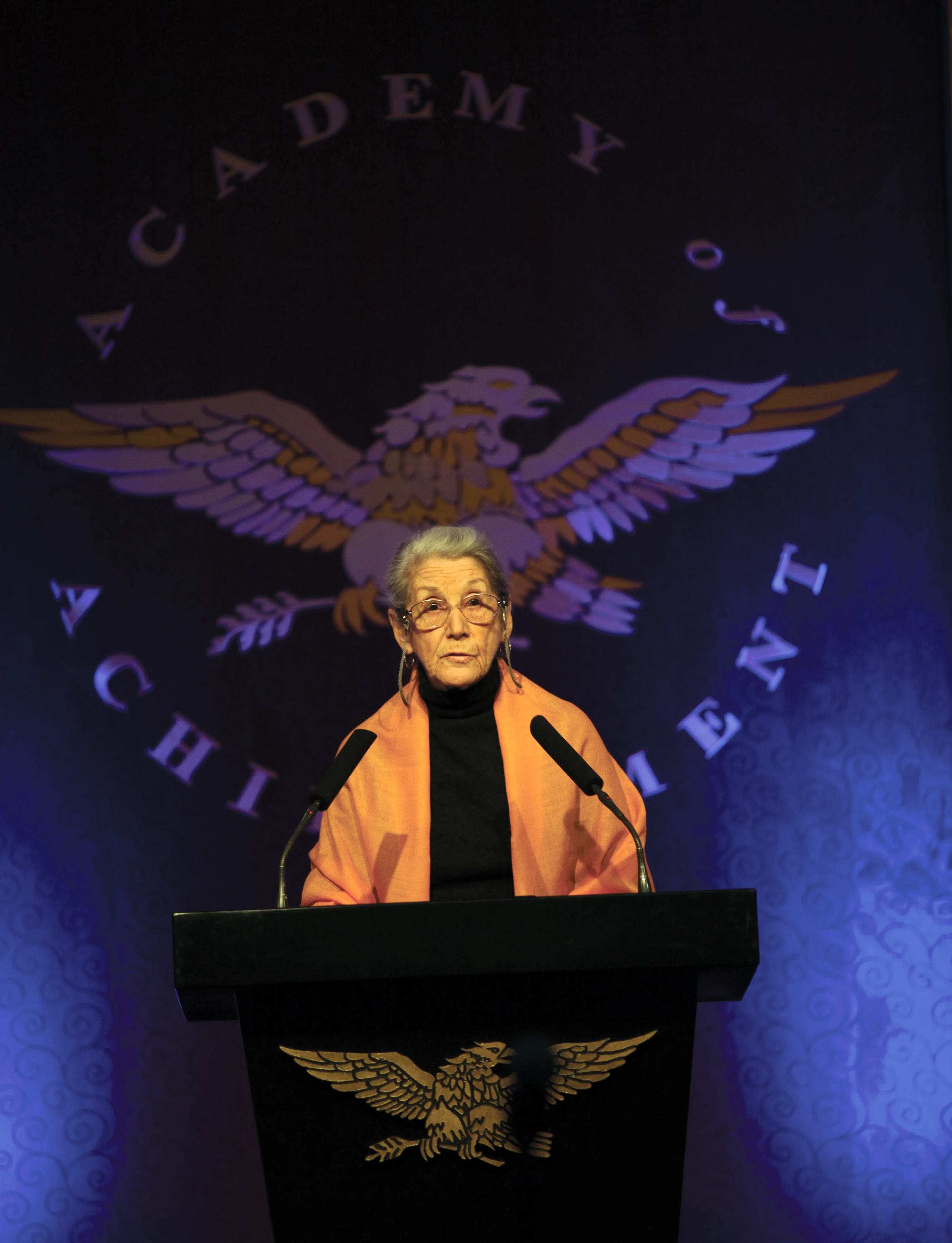

Can you tell us about the day you heard you had won the Nobel Prize for 1991?

Nadine Gordimer: It happened to be that my husband and I were visiting our son in New York, and I got up early and tiptoed through the house to the kitchen, because of the time change and so on, to phone somebody that I wanted to speak to urgently in England. But when I got there, to my amazement the phone rang. And I picked it up and it was to tell me that I — because what happens, as you know, when you get on the list, it goes on for years. And the last two or three years before that, at least two years before that, journalists would phone me and say, “You know, you’re on the top list. You’re one of two people up there,” and “How do you feel about getting a Nobel Prize?” And I would say, “If I ever get it, I will tell you. Goodbye,” and put down the phone, which is the only way to deal with it. Of course one of the nice things about getting a Nobel Prize, first of all it gives you a voice with certain causes that you may be not keen on, but that you are attached to and enthusiastic about. People will listen to you now. And also, of course, you have to learn to say, “Thanks, but no thanks,” because people don’t quite remember what you got the prize for. They think you’ve got it for physics or peace or something and so you get invited to come and speak somewhere, it’s not in your field at all. But okay, that doesn’t really matter. But one of the perks, I would say, is that after that, you have the privilege every year of — this time of year now, just about to do it again next month — of sending very secretly your nominations, who you think should get it next time. I think that’s a very good idea. They ask those of us who have it. Now, as I got it in ’91, that’s a long time ago, isn’t it? And I have done this faithfully every year. I’ve only had two successes when I coincided with obviously others. The one was a Japanese writer, Kenzaburo Oe — wonderful writer — and Günter Grass. I could never understand why they hadn’t gotten it before but they hadn’t. So I was absolutely delighted. But other times, for the rest of the time, I have not had success, but I keep on.

That morning in New York, was it a reporter who was on the other end of the phone?

Nadine Gordimer: I can’t remember who it was who had called from England. Yes, it must have been a reporter. Yes, from England.

Did you wake your family up?

Nadine Gordimer: I went back to my bedroom and shook my husband and said, “You wake up.” He said, “What is it?” I said, “I’ve got the Nobel Prize.” Of course we then had a celebratory breakfast. But when I came back here, that was wonderful, because my friends in the ANC — of course I was a member of the ANC for a long time then already — and my writer friends, especially my writer friends, came to the airport and someone blew the ceremonial horn. You know, the one that has now become a sort of trumpet for sports things, but blew that, and then they gave me a wonderful party afterwards. And the speech at the party was made by no less a person than Walter Sisulu. So that was absolutely marvelous.

Do you think that was the best time of your life professionally? Winning the Nobel Prize?

Nadine Gordimer: I suppose so. Because I was fortunate you see. People always said, the Nobel Prize is death to you as a writer because you feel afterwards, “Oh, I must write a book good enough.” But fortunately for me, I was in the middle of writing My Son’s Story. So I just went back to my book and forgot about that. It didn’t inhibit me. The Nobel Prize isn’t going to make your writing any better or any worse. If you let literature prizes stifle you because you’re afraid that the next book won’t be so good, so what.

It was 1991 when you won the Nobel Prize. It was also a historic time in South African history. Can you tell us what it was like to vote for the first time in a democratic South Africa?

Nadine Gordimer: In ’94, oh yes. It was down here in the church. That was unforgettable, because there are all the apartments, and the workers there, who were called “flat boys” at the time, and all wore little pants with the red stripe and so on, white shorts, that was the outfit. They still wore that then. And there they were among everybody else. The residents of Park Down, of Hill Brown, the whole area around which we lived, and it was simply wonderful.

But you had already been a voter.

Nadine Gordimer: Yes, but I hadn’t voted the last time around because there was nobody for me to vote for. I was in the Party, I was in the ANC, and I didn’t feel that I wanted to put anybody into Parliament who was offered. I’m not talking about as individuals, I’m talking about the parties that they represented.

Have your political views impeded your personal goals in life in any way?

Nadine Gordimer: Oh no, not at all. On the contrary. I think they’ve released me from the little white enclave background that I came from, and I’ve had wonderful friends and some are wonderful friends still. And of course I could never have lived with anybody, been married to anybody, who had different political views.

During apartheid, the South African government tried to prevent its critics from traveling by revoking their passports. Did that ever happen to you?

Nadine Gordimer: No. Fortunately for me, you see, the things I did wrong were as Gordimer. And my passport of course says Cassirer, my husband’s name. So that helped a great deal.

What do you think someone can learn about you by reading your writing? Or are you detached from your writing, so that it would be very difficult for someone to know about the writer?

Nadine Gordimer: I can’t see the point. I’m not interesting. Whatever interest there is in me is in my work, and it’s not about me, except insofar as my breadth of experience obviously has enabled me to carry on with it for so long.

You think you’re not interesting? People would love to read your autobiography.

Nadine Gordimer: I’d never write an autobiography. Why should I? My private life belongs to me and the people with whom I’ve lived it.

Many readers see strains of feminism in your works such as The Pickup. Is it feminism or is it just the case of a strong female protagonist?

Nadine Gordimer: Well what’s the difference? Isn’t that what feminism is? How should I put it? I am often getting into trouble with feminists because I don’t belong to feminist organizations. And I’m indeed a feminist, as I am a humanist. I believe that everybody should have the same rights, whether you’re black, whether you’re white, whether you’re any mixture, whether you’re male or female. And obviously women have been and are still very much, how should I put it, deprived of their full rights, many of them. So naturally I’m on that side. Women should be paid the same as men. They should have the same opportunities, all these things. They should have the same authority in their family in all kinds of decisions. Insofar as that’s concerned, indeed, I’m a woman, therefore I am a feminist. When it comes to the arts, I have a different view. For instance, the idea that there are associations of women writers. To put it quite bluntly, you do not write with your genitals, you write with what’s up here. So why must there be this distinction? You don’t have associations of men writers. God knows it’s coming, I’m sure of it. We certainly have associations that have homosexual writers, lesbian writers. Then it’ll be writers with blue eyes or writers with black eyes, you know. When is it going to stop? We all are writers, and we are influenced perhaps by our sex, which is so interesting, and especially since for millennia, for recorded time, they’ve had different roles. When you think that now we’ve got women, even from the last big war, women in war. We have women pilots now. We have women presidents in Germany and so on. But this is on the ability, which has been denied for too long, and which I think was inferior to that of men, because look how women were kept at home and not allowed to follow their education or talents and so on, their educational possibilities. So we’ve had to come through all that and I’m all for it, just as I am for blacks or for anything involving race, color, sex. Hard enough to be human without dividing it up that way.

How is your process different, writing a short story as opposed to writing a novel?

Nadine Gordimer: Sometimes a story occurs to me. And a story is like an egg. It’s complete. There’s a shell, the white and the yolk. Well now, a short story comes to me complete, the beginning, the end, and how I’m going to get there. A novel is different. A novel I always know the beginning and I think I know the end. And then it goes in stages, it develops. I do not have it complete at the beginning. Theme I have, yes. Characters, not all of them, others may come along as I’m writing. So it’s a completely different thing.

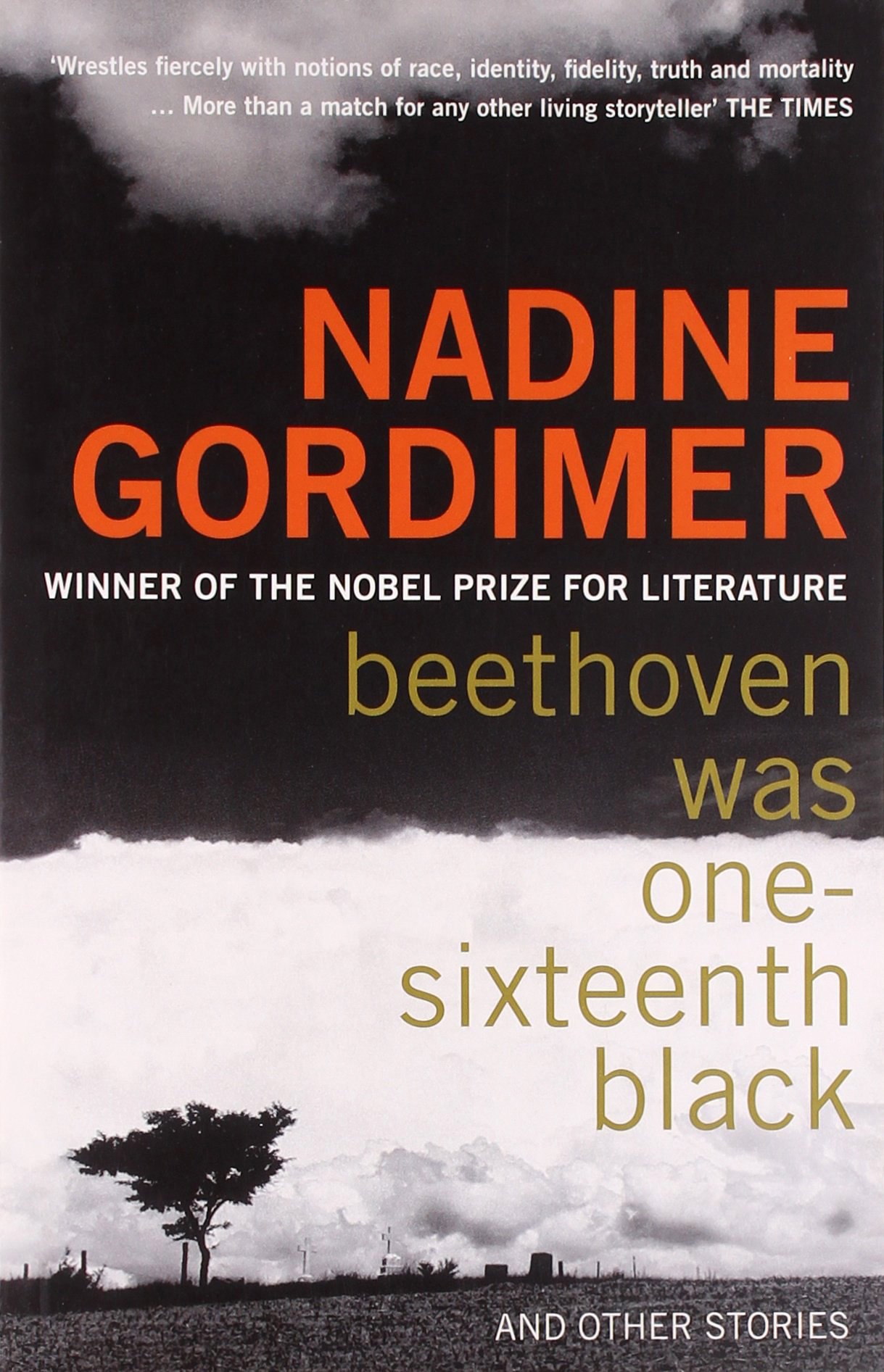

What was the impetus for the stories in Beethoven Was One-Sixteenth Black?

Nadine Gordimer: Well, how could I say? Because that consists of stories written over three years so there were many impetuses.

Did you write them all in sequence, or in between writing a novel?

Nadine Gordimer: I think in between times, I wrote a novel, yes. When I’m writing a novel, occasionally an idea comes for a short story. I jot down two words or something, three or four words, and come back to it maybe when the novel is finished, but I don’t usually interrupt the novel to write a story. But both forms, they are very different and both appeal to me as something that I want to do.

Did you write today? Can you tell us what you’re working on now?

Nadine Gordimer: I did write today. But mostly I was having to do some research as background to check on certain dates that I think I muddled up in what I wrote yesterday and the day before. Because if a piece of writing has a sense of time and sequence in the lives of the people, you want to be sure you’ve got it straight.

Was it a short story?

Nadine Gordimer: I never tell what I’m writing. I never discuss it, no.

We had to ask. A few years ago, you put together the anthology Telling Tales, as a response to the HIV-AIDS crisis in South Africa. How do you see that situation today?

Nadine Gordimer: Well, to get to the beginning, I don’t live in an ivory tower. I am very concerned about AIDS, and although I know Thabo Mbeki and I respected him for many things he did, I’ve never understood and I still don’t understand his attitude of AIDS, his disbelief of how it exists and where it came from. So now, what do you do? I’m not a politician. What can I do about AIDS? Talk about it as we are doing now? You know, tut tut. But then I thought, look what the musicians do, especially the jazz musicians. Look at these great gigs that we’re having everywhere. First of all, they made money for people who were supporting people who have AIDS, or for prevention. And secondly, they were rousing people’s attention to this. But I thought, where do we register?

For instance, the wonderful international organization to which I belong, PEN. Many people don’t know this, but they have been wonderful for two generations now, over writers who are in prison and taking care of their families and keeping in touch with them and agitating to get them out and sometimes successful. But not a word about AIDS. It’s considered, first of all, this has got nothing to do with them. Has nobody who was a writer ever got AIDS? So I said, “There’s no good carrying on about this. Do something. ” I went, well okay. We can’t have gigs. We haven’t got that enormous access to people.

What about a collection of writings? Which would not be about AIDS, but which will be attractive writings, which will make a lovely Christmas or birthday present, and the money would go to — I chose ours, the Treatment Action Campaign. So I wrote to writers, 20 writers — no, 19 because I’m the 20th — and some of whom are my close friends, and others I knew wrote really good stories. You know, not all novelists write good stories as well, but the ones that I chose indeed do, or did. A couple of them or less have died now. And told them, “Please, a story. Don’t sit down and write something about people getting AIDS. Just choose one of your best stories please, and send it to me and I’m going to find a publisher for a book. And these stories will be collected there, and the proceeds — the royalties — will go indeed to organizations that are dealing with people who are HIV positive and all have AIDS. I got a wonderful response. No refusal from anybody, which was really great. And then I thought, now the stories are going to come. All the stories are absolutely outstanding. I happen to have a couple of favorites among them, but they’re all very good. And then I spoke to my own publishers and I sent the material to them. They agreed to publish, taking only production costs and no share of any royalties. It’s now in 15 languages worldwide. So in a small way, it doesn’t do what a big gig does, but it has reached people and it has brought in quite a bit of money.

Why did you decide to do it at that time?

Nadine Gordimer: Because the musicians were doing something. The writers were not even opening their mouths, not even PEN. So what’s the matter with us?

Telling Tales was published in 2004. How do you see the AIDS crisis now in South Africa? Where do you think that we’ll be in five or ten years?

Nadine Gordimer: Well, I was just hearing today, again, on the news, we seem to be the worst affected in the world. So it’s a terrible crisis, and I don’t know, we seem not to be dealing with it. So it’s very, very troubling.

You’ve said that it was an important symbol that Barack Obama is of both white and black parentage. Did you say that it was “even better”?

Nadine Gordimer: Yes, I did. Because I thought, “How wonderful. In him, in his own body and in his formation of his thoughts and personality, he brings black and white together.” They say this is the first black President, but he’s not black, he’s both. Even better, the symbol and the way it ought to be.

Where do white South Africans fit in the new post-apartheid South Africa? What do you see is the ideal role for a cohesive existence?

Nadine Gordimer: If they’re allowed to, by the natural feelings of resentment of blacks that whites hogged everything for centuries, that there should indeed in time be no distinction at all. I’m not saying this necessarily has to come about, because we’ve got a mixed population, biologically, though I’m all for that as well. But we’ve got to stop looking at us as separate and not as South Africans.

As I always say to European friends and friends in America or anywhere, we have had only 15 years, after centuries. Since 1652, when van Riebeeck landed at the Cape, there has been racial prejudice and racial separation. How can it be fixed in 15 years? I’m not excusing the things that we are not doing, but I’m simply saying to these people, vis-a-vis racism and class difference, “Have you achieved, in several hundred years at least, a real democracy?” I don’t think so. You still got very poor people. You still got prejudice in terms of race and religion and heaven knows what.”

I mean, religion is a tremendous division between people. I always used to quote Scandinavian countries. But now it seems that the Swedes are very concerned because they’ve got so many refugees who are not white. So the whole business of difference comes up, and it’s mixed with economic opportunities and it’s a very complex thing. But unless we can have a comet, then I don’t know what will happen to whites. But if there should exist no more as white, then there will come a time when blacks will feel, “What have we done?” We either are all South Africans — and in a way I think we should drop the “South.” We are Africans if you’re born and brought up in Africa. And if you indeed respond to the new South Africa — but when you get incidents like the Free State students, you just wonder.

Tell us, please.

The Free State students went in, in ’07, they held what was called an initiation ceremony, as I think often happens among students, yes. But this consisted of inviting the cleaners — five cleaners in their hostel, black of course, four women and a man — to come and party with them. Now you can imagine how this must have seemed such a nice gesture from the students. But what they did was, first of all, they made them drunk, then they made them dance for their amusement. And then they fed them food, and in the stew, one of the students had peed. He pissed into it, and they were forced to eat it. I mean, they didn’t know that it had happened, but when they tasted it, it tasted awful and they spat it out and they were told, “Come on.”

Now, this was at the University of the Free State, traditionally an old Afrikaner stronghold. These were four young white men. Now they made an unfortunate mistake. They were so proud of what they were doing, they made a video of it and somebody got hold of the video. This happened in ’07, but the tape was only produced some months later, and you can imagine the shock when we saw, in the papers, excerpts from it, and saw this young man standing there doing this, and then these poor people. Now, the University principal, when it was exposed like this, said, “Well, they’ll come before a disciplinary committee.” Well that dragged on and on, and we didn’t know what happened. It seems that one of the students either voluntarily left or was expelled, and I thought, “How unfair!” If they all watched, they were all equally brutal. The others just continued, and what the disciplinary thing was going to be we didn’t know at all. Human rights, they have just come into it very recently this year, and have said that, indeed, they should come to the court of law, which is true, because it was a criminal act under our constitution. So that’s sort of hanging in the air. It hasn’t come, and these things get put off as they do, like our corruption trials, but it was a tremendous shock. There are many ways to look at it.

When you see the pictures of these young men, the white men, they look perfectly ordinary, rather nice face, nothing brutal looking about them. So what kind of upbringing did they have? What kind of terrible racist ethos was placed into them by their parents? And I mean they’re young. They’ve grown up since our country’s supposed to have changed. So that was a bit of a shock to us all. Right? We hope it’s an isolated incident, and certainly of such vulgarity and cruelty. Now another point has come up, only two weeks ago or last week. Who at all has talked to the four people, the four cleaners? What’s happened to them? They must be compensated. Well, they have spoken and said, “Very well, but how can you compensate for what happened to us?” But of course, under our constitution, the lack of dignity counts. So all these things are now still to be dealt with. But it’s so good that these things come up now, and then there be a lot of argument about them, but that’s part of dealing with them.

Do you think the threat of violence is part of the fabric of South African culture?

Nadine Gordimer: Oh, that is a big question. I’m trying to think where it isn’t. I really can’t think of any country — not in our time and perhaps in any time — when violence hasn’t been part. It’s part of the human state. I mean, the animals, they’re not violent. They kill. Predators kill because they’ve got to eat. But we kill. Only human beings kill in power positions, whether it’s a personal power position among lovers, if it’s ambition or if indeed it is politically motivated. So we are, I’m afraid, unique in that. But I think it is… How shall I put it? It’s endemic, and it’s very, very deep. It’s congenital. Alas, alas, alas.

Do you think freedom is a condition of happiness?

Nadine Gordimer: No. If you think of it as a condition of happiness, that’s saying, “I believe in paradise.” Happiness is something that comes from many different aspects of life, but I don’t think happiness is possible without freedom. I would say that.

What do you know about achievement now that you didn’t know as a young person?

Nadine Gordimer: Life is one experience after another and it’s a mystery. As a writer, I would say that as writers we’re exploring the mystery, the mystery of existence. Not in the same sense as philosophers do, but whether you’re a painter or a writer, when I think of my friends who are painters, in their way, they’re doing it. In my way, I am. And of course, in the very practical sense, in the public sense, that is what people are doing in politics, when they achieve things in politics. And we’ve had some wonderful achievers, starting with Mandela, Albie Sachs, the extraordinary personality that has accepted all the things that have happened to him and never become bitter. So that I would call achievement, tremendous achievement. It’s different in every field.

Has it taught you something specific, looking back, that you couldn’t have imagined as a young person?

Nadine Gordimer: That’s been happening all my life, and it’s still happening. Not just in my writing but in my relations with other people.

One last question. Do you think you’re writing a history of South Africa’s conscience?

Nadine Gordimer: No, no, no, South Africa’s conscience, of course not. That, I say, is a political task.

What do you want your legacy to be? What would you want your verbal footprint to be?

Nadine Gordimer: If I have one, it’s between the pages of books I’ve written.

Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with us today.