The decision by The New York Times to publish the Pentagon Papers was a very controversial one. Was there any hesitation on the part of your editors?

I was very proud our executive editor — A.M. Rosenthal, he was called — Abe Rosenthal. The staff counsel, the lawyer for the paper hadn’t heard anything about this, and he was brought into the room too, and kept saying to me, “Don’t tell them this.” He kept whispering in my ear, “We may have committed a felony here. Don’t tell them this,” and I said, “But I have to tell them. It’s their responsibility. They’re the editors.” I held nothing back. I outlined what we had and how explosive it was going to be. We were not going to compromise the national security of the United States, but it was full of political and historical secrets which were going to cause an explosion, because that’s what politicians care about. You could print a formula for a nuclear weapon, and that won’t really excite them, but if you print something that reflects on their reputations and says they made a mistake, why that drives them right through the wall.

Abe never said to me — he called me over to his office after the main briefing, and he sat me down, and he said, “Now, look, how do we know these things weren’t made up by a bunch of kids in a cellar?” This is the time of the hippies and the flower children and all the revolution. “How do you know this is authentic?” and I said, “Well first of all, I know the people who I got this from had access to the real thing, and secondly, I have read enough of this stuff as a military correspondent,” because people would give me classified documents. I said, “This is real. There’s nothing fake here.” He didn’t entirely believe me. He had the foreign editor who had been in government — a man named James Greenfield — read some of this stuff, and Jimmy said, “Yeah. It’s for real.”

And then…

This tremendous battle occurred within The New York Times between Rosenthal and the other editors, mainly the business side, and the main legal counsel for the paper. The outside counsel was a famous establishment New York lawyer named Louis Loeb, who told the publisher that if he published this material, the government would take him into court, and he would lose against the restraining order, and Loeb would not defend him! He would refuse to defend him. It was such an arrogant, incredibly arrogant thing to tell a man who’s running The New York Times and whose editors are telling him, “You’ve got to publish this material. This belongs in the public domain. We have a duty under the First Amendment to publish it. It doesn’t matter what these people say. You’ve got to publish it. That’s it.” The publisher, Arthur Sulzberger, who also was called “Punch,” the father of the current publisher, decided to go ahead and gave the editors their head. He fired the chief counsel afterwards. He fired Louie Loeb.

Fortunately, the staff counsel who had been whispering in my ear in that meeting — saying, “Why are you telling them this?” — he was a young lawyer, and he had been put in the firm as staff counsel by Loeb, and he disagreed with Loeb. He said, “Look, you are wrong, Louie. We have a right to publish this under the First Amendment, and if we are taken into court, we will win,” and he turned out to be correct, but…

They didn’t have a lawyer to even go to court when they got a telegram from Mitchell saying, “Stop publishing and hand over the documents or meet me in court in the morning.” Fortunately, they pulled a very good judge who believed in the First Amendment, who was very conservative. He was a Nixon appointee, and it was his first week on the bench, and it was his first case. His name was [Murray L.] Gurfein. He was a Jewish Dewey Republican, which was a rare beast in New York. Most Jewish figures who were involved in politics were Democrats, but not Judge — what became Judge — Gurfein, and he had been a very conservative lawyer, but he believed in the First Amendment, and he was a good lawyer. And he said to the government, “Okay. Now show me what’s ‘Top Secret: Sensitive,’ in this.” “Well,” they said, “It’s all.” “Wait a minute. You’ve got 7,000 pages and a million words. It can’t all be ‘Top Secret: Sensitive.’ What is it that’s going to compromise the national security?” Because the government came in with a restraining order, with a case that if we continued to publish, it would cause immediate and irreparable harm to the national security. He said, “Okay. Now show me what’s going to cause harm,” and they couldn’t show him anything. This man had been in the Office of Strategic Services during World War II. He had been a colonel. So he wasn’t an entire dummy.

At first, he was very unfriendly to the Times lawyers, because he lived in New York, but he wasn’t accustomed to what, post World War II, became known as “political classification,” classifying things to keep them out of circulation. He thought if something was top secret, it really was top secret, but his eyes were opened. He opened his own eyes, and he wrote a resounding opinion, but then he was reversed. We published for three days, and then we were stopped by the restraining order. The Washington Post got hold of a set, and they started publishing, and the government took them into court, and their case moved quickly to the Appeals Court, so it was getting ripe. It was ripe for the Supreme Court. So the Times and the Post went to the Supreme Court, and they found in our favor. But yes, it was a momentous adventure to take part in.

It was like going to war. I mean, the strain, the tensions on you were tremendous. First of all, we were in the Hilton Hotel working on this thing for two months before we published, and the strains, they were horrendous. It was a huge amount of material. You had to boil it down, decide what was the most important stuff. Then you had to hand that out to four reporters, each of whom wrote three pieces approximately. And then you were up against the situation where, as soon as the executive editor got the go from the publisher, he was going to go. And then we got into this legal battle, and you had all the tension of that. I remember the day the Supreme Court decided in our favor, that night I went down to the press room to see the presses roll — and then the presses were in The New York Times building on West 43rd Street — and what a wonderful thing it was to see these giant presses start to roll and the paper come off! It reaffirmed your faith in America and in the freedoms we ought to enjoy, and it reaffirmed your faith in the worth of American journalism, of free journalism in a free country.

When and why did you decide you had to write a book about Vietnam?

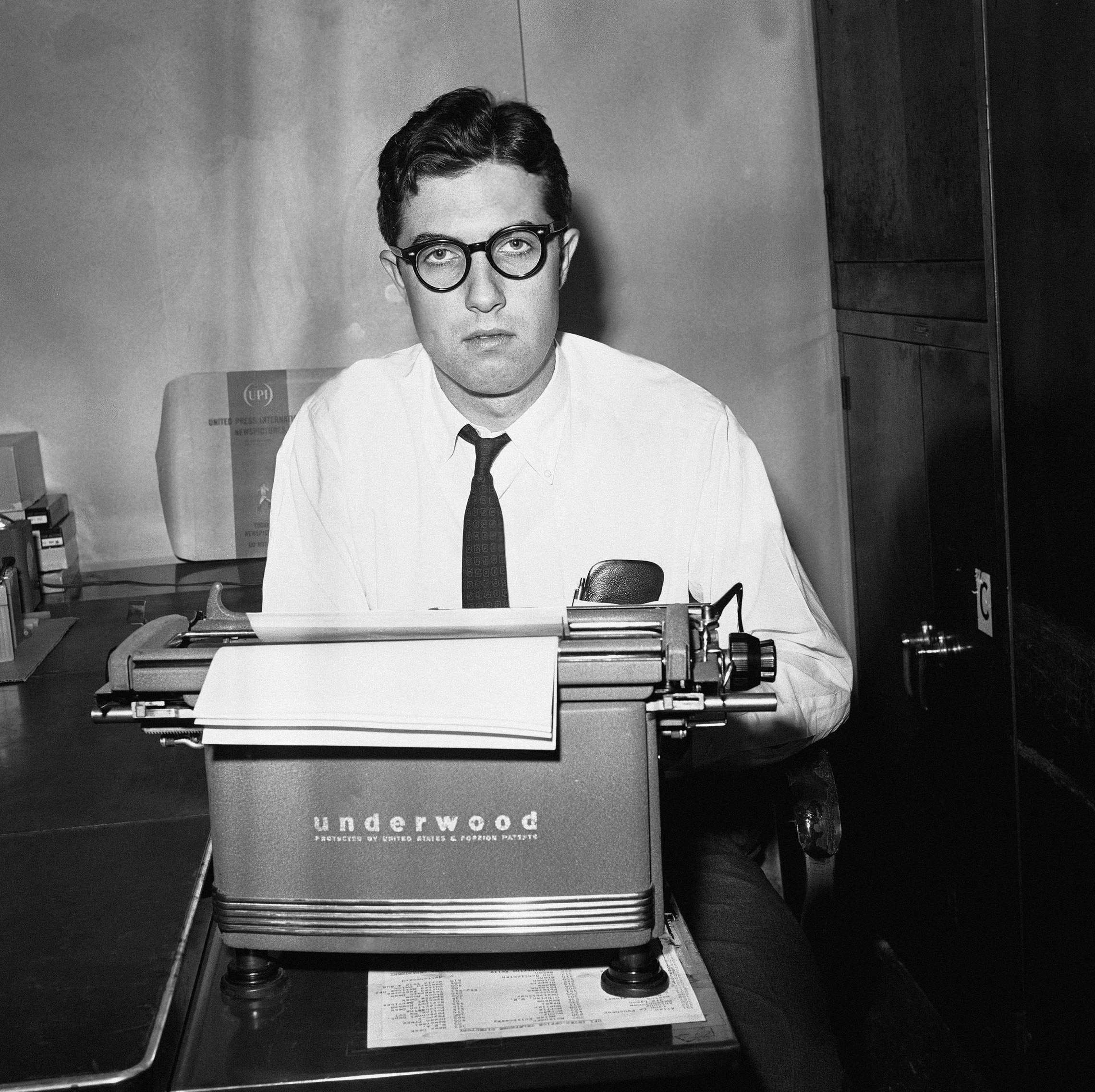

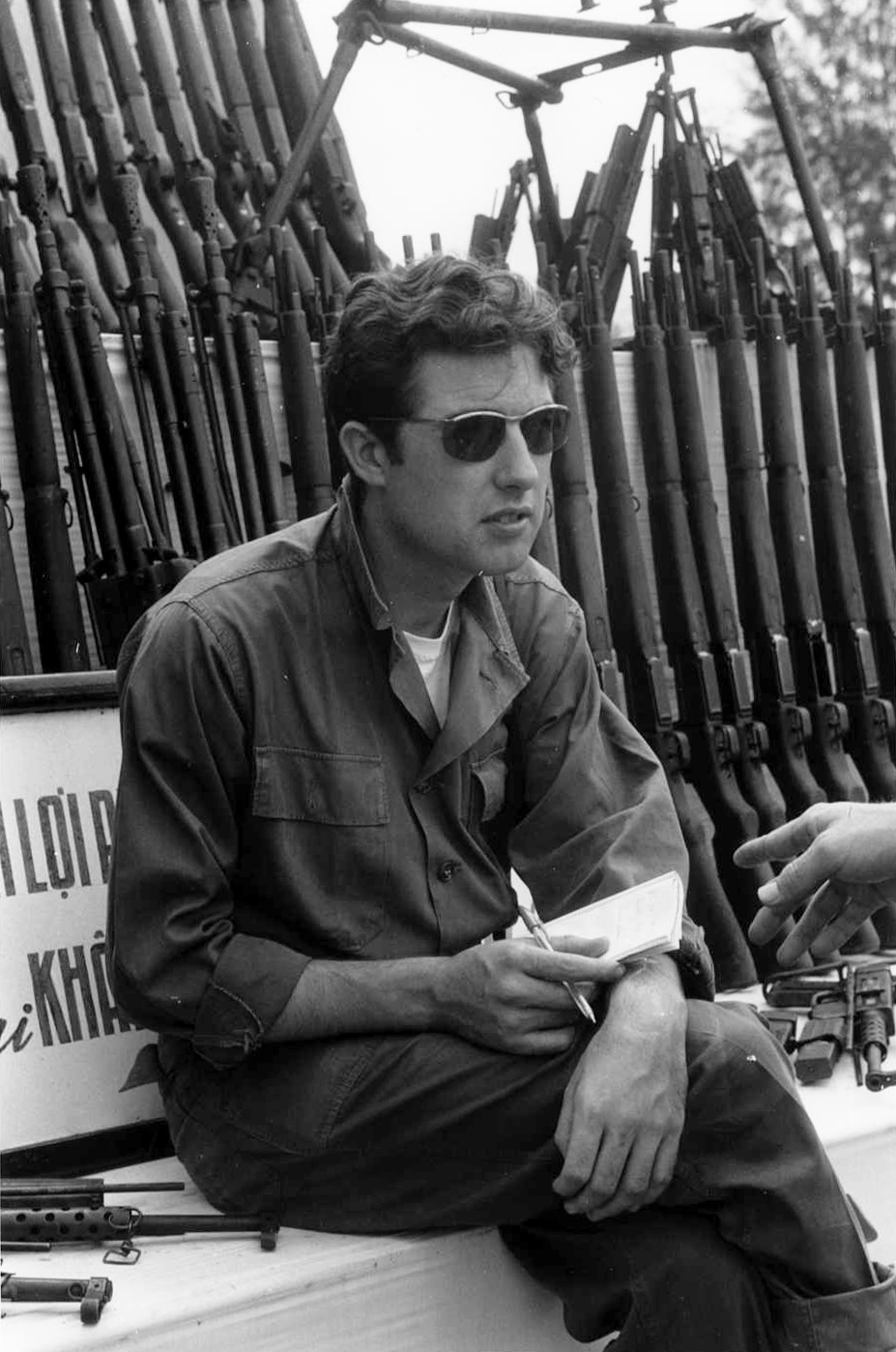

Neil Sheehan: I never got away from the war. I was sent down at the age of 25 in April of 1962 by UPI. I spent two years there. I went to Indonesia for six months, after six months in New York, but then I went back for another year for the big American war. I saw the two phases of it begin. Then they sent me to Washington to be the Defense Department correspondent. So I was covering the Washington end of the war. Then I was White House correspondent for six months, still on the Washington end of the war. The war dominated everything here. Then I didn’t want to go back to the Pentagon, so I asked to be made investigative reporter for the Bureau for Political Military Affairs, and they said okay, and I was back again. Not as often, but I was still with Vietnam. And then the Pentagon Papers came in ’71, in the midst of this, when I was an investigative reporter for the bureau. Again, Vietnam, in a very traumatic, emotional, exhausting, but fulfilling way.

I then began to realize I want to write a book about this. I don’t want to just end this with another magazine article or another newspaper story, but I couldn’t figure out how to write the book. I didn’t want to write a reporter’s memoir, because it’s my belief that reporters themselves are not that important, not important enough to merit a book about them and their adventures. Their importance lies in what they witness and how they convey what they witnessed to the public as a whole, because a reporter is a professional witness and not a participant. He’s a witness, or she’s a witness.

Then Colonel John Vann died. I had gone with him on my first helicopter operation in May of 1962 when he was the senior advisor in the northern Mekong Delta. I had gone out with him on a first assault, ’62, and I stayed friends with him through the years. John had other disciples besides me, and other friends, and almost all of them turned against the war, but John stayed with the war. It’s the one thing we totally disagreed on by the end, but he stayed there in Vietnam.

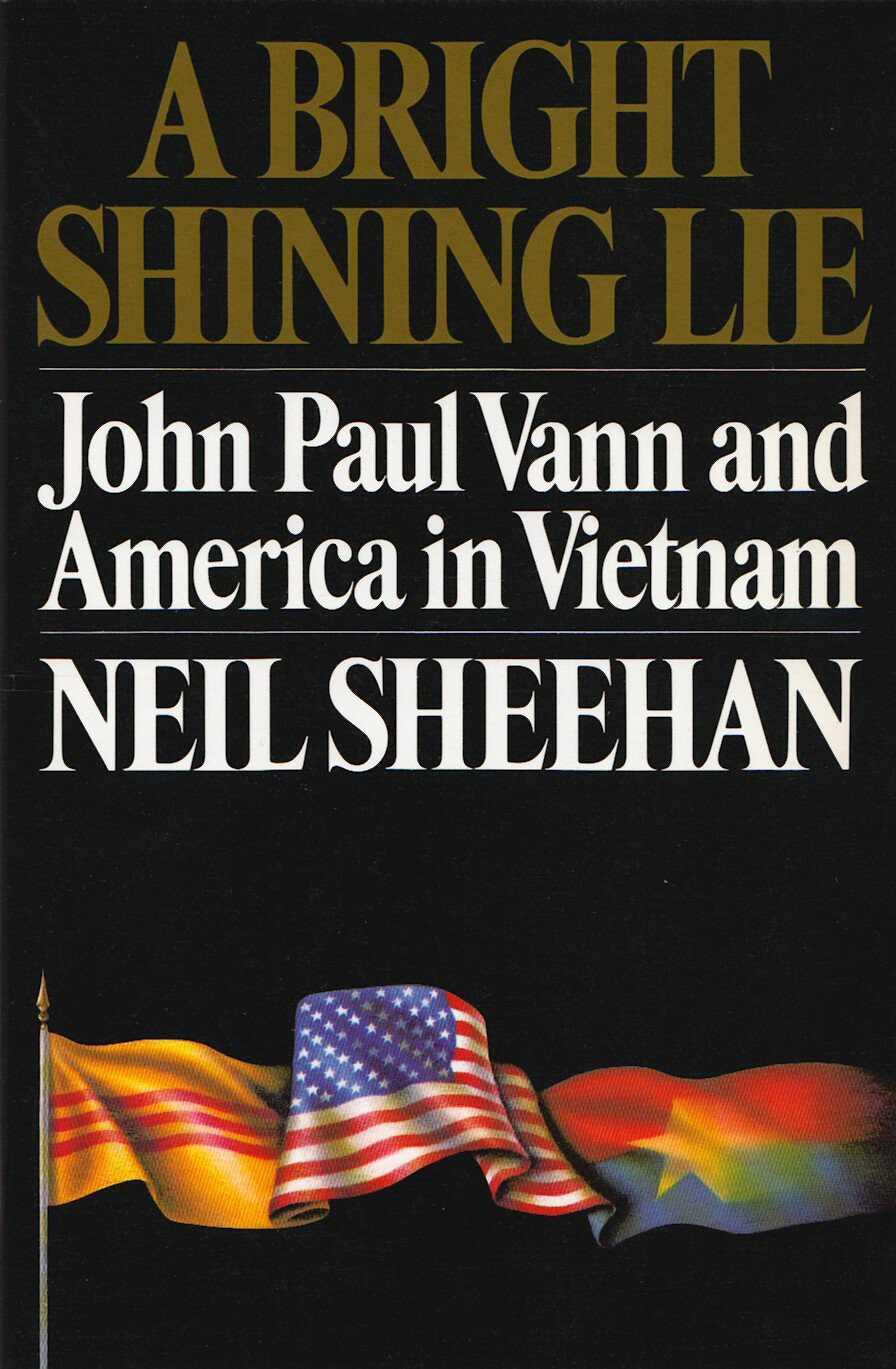

Most people went to Vietnam, they stayed one year, two years at the most, three years perhaps, and then they came home. John stayed there for the better part of ten years, from ’62 until he was killed in June of ’72. So by the time he died, he had become a personification of the American war in Vietnam, and I went to his funeral in Arlington, because he was a friend. By that time, John was a civilian, because he retired from the Army in ’63 or ’64. He had retired, but he had been on detail to the Army, and he was the equivalent of a general. In fact, he was the first — and so far the only — civilian in our history to hold military command in war. John had a deputy who was a brigadier general. They assigned a brigadier general to him as his deputy, so it would be legal, because the deputy could exercise court-martial authority, but John was the corps commander.

In your book A Bright Shining Lie, you talk about John Paul Vann’s career in the Vietnam War. Could you tell us something about the significance of his actions there?

He stopped the North Vietnamese offensive of 1972. The whole thing would have come down in 1972 if it hadn’t been for John stopping them in the mountains. The country would have disappeared then, because it was falling apart, and he, by sheer force of will, held onto this town in the mountains which became a focal point, and the Vietnamese didn’t go around it. They fought in there, and he defeated them with B-52’s and everything he could bring up there. Plus, he managed to get a Vietnamese division. He had been there so long that he could take a Vietnamese division whose commander he had maneuvered into place, a Vietnamese, and fly them into that town, and they’d fight. There was the Vietnamese commander, and the officers would stay there, because they figured John would get them out at the last moment if things failed. In fact, he wasn’t planning on getting them out on that occasion. This was the end, because if he lost that, he’d lose his reputation and everything. So he had come to personify the American venture in Vietnam.

When I went to the funeral, it was an extraordinary experience to walk into that chapel at Arlington, that red brick chapel right outside the gate to the cemetery at Fort Myer. It was like a class reunion. They buried him as a general officer, with the horse and the caisson and all the trappings. The chief pallbearer was William Westmoreland, who had been the commander-in-chief in Vietnam, and William Colby, who had been the CIA head at one point, was another pallbearer, and here are all these others. Edward Lansdale, who put the Diem regime in power in the 1950s for the Eisenhower regime. He was there. Richard Holbrooke, who had been a young foreign service officer in Vietnam and went on to become the youngest Assistant Secretary of State for the Far East. All these faces. I’m saying, “Hi.” It was extraordinary. I realized that only this man, Vann, could bring all these people together, because he was such a unique figure. So I decided if I write a book, a biography of John, I can reach out to the larger history of the war and to whom the Vietnamese are, et cetera, and I can bring them into the story, and that’s what set me off writing the book.

I came back from the funeral, and I called my wife, who is also a writer, Susan. Susan won the first Pulitzer in the family, not me. She won it for a book on mental illness called Is There No Place on Earth for Me? She wrote for The New Yorker. She called me from the Library of Congress, where she was working, writing, and she said, “How did the funeral go?” I explained this extraordinary funeral to her, and she said, “Maybe that’s your book.”

I started to write. It took me a long, long, long time. I had some problems. I had an auto accident. I lost a year over that. I lost a year over something else, but it basically took me — if you added it up — it took me 13 years of research and writing to get the book done. A Bright Shining Lie, that is, John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam. But I’m glad I did it, because I wanted to leave a book behind. I wanted to record this experience for those who had been there, for those who had fought there, for the general public at large, and for the generations to come, and also, I guess for myself. I wanted to get it down and convey it, because it had been the experience of my life for ten years.

How did you persevere that long? You had an auto accident during this time that almost killed you.

Neil Sheehan: Eleven broken bones.

Didn’t you ever feel like giving up?

Neil Sheehan: I almost gave up at one point because I ran out of money, and Susan couldn’t support the family by herself. We had two daughters going to private school. It was 1979, and I had enough of the book done so that I knew I had solved my problems. I had a lot to write, but I had solved my problems. I knew where this thing was going, and that I had a vision of the book now, and it was working, my vision, but I was going to have to stop to support the family, go back to reporting.

I had a friend who had been a reporter in Vietnam. His name was Peter Braestrup. He was an ex-Marine, and he was running the Woodrow Wilson Center’s Wilson Quarterly at the Smithsonian. I ran into him in a supermarket, and he said, “How’s the book going?” and I said, “Well, I finally found my way. I can see the way ahead, and it’s working, but I’m going to have to quit because I’ve run out of money.” He said, “Why don’t you apply to the Wilson Center for a fellowship?” I said, “Peter, nobody is going to give me another fellowship. I’ve been at this thing since 1972. I lost time over the accident and stuff, but nobody is going to give me another fellowship. I had two or three.” He said, “I’ll put an oar in for you. Apply.” So I applied.

The current Librarian of Congress, James Billington, was then head of the Woodrow Wilson (International Center) for Scholars, and he got me a fellowship for one year, which was a good fellowship then. It was the equivalent of a salary, and that year tided me over, and then we had another slim year, and then I had about two-thirds of the manuscript. I was able to go back to Random House and say, “Okay. Here is what you are going to get if you give me some money, enough money to finish this thing,” and they read it and they said okay. Now they could see what they were going to get, because we had to renegotiate the advance, and they gave me a bit of money. And then I ran out of money again, because it went on for some more years longer, and William Shawn, who was head of The New Yorker, was going to take 125,000 words. He gave me $40,000 advance, and so I was able to keep the family going. I finally finished it in 1987. We published in ’88. I finished it. I basically finished the manuscript in ’86, and then it took me a year to cut. It was too long, much too long. It was 475,000 words, and my editor and I had agreed that 375,000 was the limit. So I got a computer, learned how to use a word processor, and I took 100,000 words out of the manuscript with the help of my editor, Robert Loomis.

He would read it and approve it, and then it took about a year to go to press because they did a very good, very careful job of going to press. We had maps and photographs and all this sort of thing.

How hard is that for a writer, taking 100,000 words out of your manuscript?

Neil Sheehan: When you’ve written much too much, as I had then, and you’ve got a vision of your book, it’s hard work, but it’s not heartbreaking, because I was producing a better book. It was going to be better. It was a long book. It’s a big book. Harrison Salisbury was a friend of mine who wrote that wonderful book on the siege of Leningrad, The 900 Days. I was in New York and I sent him a copy. It weighed three-and-a-half pounds and he said, “If you’re stopped by a mugger, drop it on his foot.” But I knew I was producing a better book, so I was not unhappy cutting those words. They had to come out.

While you were doing it, were you aware of just how important a book you were writing?

Neil Sheehan: Not really. I wanted to write a definitive book on the war. I wanted it to be definitive. I wanted it to encompass not just the American side, but also the Vietnamese, who they were, what had happened. I wanted it to be definitive. I hoped it would be widely read. I couldn’t have known the reception it would receive, no, but I was putting everything I had into it. I mean everything I had learned, all my skills that I had built up over the years were going into that book. It was exhausting. I thought I’d never write another book afterwards, because it was exhausting. I got so tired by the end. You’d get up in the morning — and you’d be exhausted — to start the day. You’d be so nervous, my hands would shake until I got the manuscript going again, my next segment, the segment I was working on. You’d get nervous. I had terrible stomach cramps for a long period of time from nerves of the whole thing, because your nerves get to you. You think, “When is this going to be done?” You see the end, but to get there! You know the path. What I should have learned was you don’t look at the top of the mountain, just look at the step in front of you, but it’s hard to do that. You keep seeing the top of the mountain. Jesus! Mother of God, it’s a long way away! I’m glad now I did it. It took up all my middle years. I started it in 1972, and I published it in 1988, and my middle years all went into it, but I am glad I put them into it.

Otherwise I’d have just been writing newspaper stories. It’s a worthy profession. It’s a good profession, but the newspaper, after it’s published, is something to wrap the fodder in the next day. It’s a worthy thing. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not denigrating it, but it’s not the same as a book. A book sits on the shelf, and I really wanted to do this. I’m glad that I had done it.

What was it like growing up in Massachusetts when you were a kid?

Neil Sheehan: It was a wonderful time to grow up where I grew up in Massachusetts. I grew up on a dairy farm in western Massachusetts, right on the edge of a town called Holyoke, named after an explorer who had come through the area. There is a mountain called Mount Holyoke which is also the name of the college, not in Holyoke, but in a place called South Hadley. There was one murder the whole time I was growing up, and it was a political killing, apparently, of an alderman who got out of line. But the schools were good.

I went to public schools. My parents were Catholics, Roman Catholics. My mother was quite religious, but for some reason, she did not send us to a Catholic school. She sent us to the public schools. Discipline was very strict. My mother used to say to the teacher the first day she took me in, “When he gets out of line, whale him good,” and they would, too. They had those long pointers, and if you misbehaved, you went down to the principal’s office — her name was Miss Moynihan — and you held out your hand. She came down on it with one of those pointers, and oh God, did it hurt! And if you pulled your hand away, she gave you an extra one. But, you know, it was lots of fun.

There was a lot of work, too. I worked on a farm. When I was 11 years old, my father put me to work in the dairy. It was a farm that went from the cows, which my father managed that, right through a pasteurization plant, and then we bottled the stuff, and then we delivered it to customers. People didn’t have automobiles then, so you got your milk delivered to you. When I was 11 years old, my father put me to work in the dairy full time, every day after school, four hours, Saturday morning and Sunday morning. Then when I was 13, I was running the dairy, and I was getting paid three dollars a day. So I bought all my clothes. I wanted to be a jazz drummer, paid for my drumming lessons, et cetera.

It was a good time to grow up in that sort of community. I got a scholarship to a boys’ school called Mount Hermon then, now called Northfield Mount Hermon. If you were young and male at that time, you could advance in that world, because the wealthy people in New England — who were referred to as the “Yankees” by the Irish — were real social democrats. They believed in social democracy. I was lucky enough to get a scholarship to this boys’ school for my last two years of high school, and then I got into Harvard and got a scholarship to Harvard because I came out very high in my class. I had to. It was the gate out of the pasture. You either made it or you were stuck.

What kind of kid were you? Were you a good kid?

Neil Sheehan: I was fairly good. I didn’t cause too much trouble until I got older. I was an alcoholic when I was younger, and I had serious problems with it, starting in late years of high school and then in college. I didn’t realize what was wrong with me. We were encouraged to drink then, and it wasn’t until I got in the Army that I discovered what was wrong with me. It was really purely by accident. I was working with a printer who was an alcoholic at the Armed Forces newspaper called Stars and Stripes. He got me into Alcoholics Anonymous in January 1961, and I’ve never had a drink since. It saved my life, because I would have gone down a bad road.

In fact, one of my roommates in college, we don’t know what happened to him. He disappeared. He was an alcoholic. So that was the one problem I had. Otherwise, I was a pretty good boy. I behaved myself most of the time.

What kinds of things were you interested in when you were growing up?

Neil Sheehan: First of all, I was interested in getting away from farm chores. When I was younger, I loved getting out in the woods, fishing. We used to go fishing at the local reservoir, but it was off limits during the war. They thought the Germans were going to poison the water and kill us all. So the reservoir was put off limits to fishing. Then I got my first rifle when I was nine years old, a little .22 I found in my grandfather’s farmhouse. We lived in a house about a half-a-mile away from the farm. Then I could get out in the woods and I would be alone and got peace. No one was bothering you. They weren’t putting you to work in the hay barn or whatever. And then I got interested in music.

I wanted to be a jazz drummer, and as I said, I paid for those drum lessons. There was no choice about working in the dairy. I was told to go there, and that was it. My father put me to work there, but it gave me a certain sense of independence, in the sense that I had $21 a week, which was a lot of money in the 1950s for a 13-year-old boy. I wanted to be a jazz drummer, and I used to listen to Gene Krupa. I wanted to be like Gene Krupa, and I took lessons, but thank God, my wrists weren’t fast enough, and so I decided that wasn’t for me.

The way the structure worked, people with money, the professional class in the town and those above it, the mill owners, took their children out of school beginning in about the ninth grade and sent them off to private school. So the public schools were very good up through the ninth grade. You could get into a good college through the public high school, but you had to really be on top of your class, and I wasn’t. I was unhappy at this drudgery in the dairy and wanted to get away from it. My mother encouraged me to get away from it, and the way you could get into a good college then was to go to a private school, do well, score very high scholastically, and you could get a scholarship to a good school. So with my mother’s encouragement…

My mother came from Ireland when she was 17 years old in 1924. She worked as a housekeeper for ten years before she married my father, and she did not want her children to be farmers. She wanted them to be educated, and she encouraged me to apply. So I went to the public library, and I got the catalogue of private schools, and I applied to a whole bunch of them. I went down to Andover, and I took the exam and flunked the algebra, and they told me I could come. I’d have to take algebra, but no scholarship. Well, that meant I couldn’t go. Then I went to Mount Hermon, and they didn’t have any mathematics on their entrance exam. My mother drove me up for the exam. I remember she said the rosary all the way up and all the way back. I did well on the entrance exam, and they offered me a full scholarship. Well, not full. I had to come up with $250, which I earned in a hayfield. So I spent junior and senior year at Mount Hermon, which is now Northfield Mount Hermon.

In my time, it was split into two schools. There was a boys’ school, which is Mount Hermon, and the girls’ school on the other side of the river, which was Northfield.

I graduated first in my class, and so I got into Harvard without any trouble. Because what was going on then was the Ivy League universities were taking basically quotas of boys. They would take ten to 15 boys from Bronx High School of Science, maybe ten from Stuyvesant — the New York academic schools. They’d take ten to 15 boys from Boston Latin. Then they’d take ten to 15 from Andover, ten to 15 from Exeter. My school was not a fancy school, and it had three, I discovered, was the quota, and since I was at the top of my class, I got in. But as I said, my total motivation was to get away from the farm, to get into a good college, to get into the larger world, and to do that, you had to get through that gate out of the pasture.

When you were growing up, were there books or teachers that were important to you?

Neil Sheehan: There were some very important teachers to me at Mount Hermon. My teachers in younger years, they were good teachers. I remember I had a good French teacher in public junior high school, but they weren’t outstanding. At Mount Hermon, some of the teachers were truly outstanding.

I had a wonderful English teacher named William Hawley in my senior year. His classes were absolutely unforgettable. Yeats, T.S. Eliot. He had us reading The Waste Land and writing essays. He taught you college-level English at the secondary level. He challenged you. And of course, there was real discipline in the classes. When the teacher came in, you stood up, and then you addressed the teacher as “Sir.” “Yes, sir. No, sir,” or “Yes, ma’am. No, ma’am,” and there was no nonsense. You were being prepared to go to college. That was the whole point. He was probably the most outstanding teacher I had.

I had a good Latin teacher, and a very good French teacher who later on became the dean of admissions. I became friends with him when I was an adult. These men were highly motivated, and so were the women. I had a couple of women teachers. One of my first-year Latin teachers was a woman. She was highly motivated, and the whole ethos of the school was you were being prepared to go to college. That was it.

The athletic program was wonderful, because I was a poor athlete, but they had the varsity, they had the junior varsity, and then they had something called the C Team for people who couldn’t make either varsity or junior varsity. We got to compete, because when we competed against Andover or Exeter or Deerfield, they also had C Teams. The head of the athletic department was a wonderful man named Axel Forslund. The gym is named after him there now, and he paid just as much attention to you if you were on the C Team as he did if you were on the varsity. He believed in boys. If your boy was motivated to play, it got his attention. We had a great cross-country coach who was also the French teacher. I ran cross-country in the fall, and I played ice hockey — which is a great, rough, tough, fast, hard sport — in the winter. I really enjoyed it. So it was a great fullness of life to go to a good private school. You got up in the morning, you had a really good breakfast, and you ran all day long, and when the “lights out” came… Bang! You were off to sleep for another day. I really enjoyed it, and the intellectual challenge was great.

As a kid, coming from a family of Irish immigrants on a dairy farm, were you intimidated by any of that?

Neil Sheehan: I just rejoiced in it. It was liberation. I wasn’t stuck in that dairy every day. Also, I wanted to get away.

Irish-American culture was very constricting in those years. The Catholic Church — the Irish Catholic Church was very puritanical and pretty much anti-intellectual. The priest had great authority, because Ireland, you must remember, is the only colonized country in western Europe, and English colonization of Ireland was brutal. The Irish were crushed. My name isn’t Sheehan, my real name. I don’t know what it is in Irish, but Sheehan is an anglicization of my original Irish name in Gaelic. It’s true of all Irish names. They’re all anglicized, except now they’ve brought some of them back. So the Irish were looking for security when they came to this country. Get yourself a job as a fireman. Get yourself a job as a policeman. And be a good Catholic.

Mount Hermon had been founded by a Protestant evangelist in the 19th century. It was non-denominational when I went there, and it was also very liberal. It was the only private boys’ school in New England that had black students and no quota on Jews. The Jewish kids had to listen to “Jesus Christ…” three times a week, unless the chaplain brought a rabbi or a cantor in to lead the service, which he did on frequent occasions. He was a very liberal man from Union Theological Seminary in New York, and so was the headmaster. It was liberation. First of all, you were able to play sports. It wasn’t like it was in public school. When I came up to bat, the kids groaned because I was going to strike out. It turns out, I’ve got a master left eye, and I’m right-handed. They didn’t test for those things then. So I didn’t know to wink when I was swinging over here and the ball was over there. At Mount Hermon, they had this wonderful rounded life, and it was a joy if you’d come from the background I had, that was so constricted.

All my aunts told me — my mother’s, my father’s brothers also, my father’s sisters — all said, “Don’t go up there. You’re going to end up with the devil, all those Protestants up there.” My mother encouraged me to go, and there was a young priest in the parish who also encouraged me to go, but I wanted to get away from my aunts. If my aunts said, “Don’t go,” that was an encouragement to go. You weren’t supposed to look out very far in the world. You were supposed to go to public school. “It was good enough for your cousin. Why didn’t you go? What are you doing, going to Harvard? Why don’t you go to the University of Massachusetts? It’s good enough for your cousin. Why should you want to go to Harvard?” The Irish as a community in that period of time were not upwardly mobile like the Jewish community. They did not have a sense of intellectual achievement built into the community, built into their cultural ethos. My mother was an exception to the rule, much, much an exception to the rule.

So you wanted to get away from that small town. It was a wonderful time to grow up in a place like that, because you got good schools, discipline, no crime and all of that, and a chance to break out. But if you got that chance to break out, you sure as heck wanted to take it.

Did you have heroes growing up?

Neil Sheehan: Not really. I liked baseball, and I liked football, but Ted Williams wasn’t a great hero. It was great to go to Fenwick Park once and see him play, but my hero, I guess, would have been Gene Krupa when I thought I was going to be a drummer, when I wanted to be a jazz drummer, and the other great jazzmen of the period like Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington. They used to come to a place called Springfield, Massachusetts, which was a city below us, which had a coliseum, and all of the big bands came through there. I guess if I had heroes as a child in that period, as a teenager when I wanted to be a jazz drummer, they were my heroes. When I went away to boys’ school, to Mount Hermon, my heroes became writers. Hemingway was a hero, and T.S. Eliot. These were great intellectual figures, great writers, people I truly admired. So if I had heroes, they were my heroes.

When and how did you figure out what you wanted to do with your life?

Neil Sheehan: It took a long time. I went to Harvard and majored in English. I thought I wanted to be an editor in a publishing house.

I got on to The Harvard Advocate, which was the Harvard literary magazine. We published once every two months. It was hard. The competition was difficult, because the people on there examined you, and you had to be able to talk well about books. If they didn’t think you were critical enough or bright enough, they didn’t elect you. I was fortunate to get elected my freshman year. All we did on the Advocate — after we edited the manuscripts that we were going to publish, the poetry and the short stories we were going to publish — was we discussed literature, everything from Shakespeare through Hemingway.

I discovered I was reading and discussing at Harvard all the courses, all the books I was taking in my English courses. I was also taking French courses, French literature, and kind of a minor in French literature. It really came home to me when I went to the course taught by the great Shakespeare expert at the time called Harry Levin, and I went and I listened to him. His lectures were basically the same as his books. He was regurgitating his books, and I had read all of the books, all of his books of criticism. I had read all of his commentary on the Shakespeare plays, and we talked them all through. That’s all we did at the Advocate, in addition to preparing the issues we were going to publish.

You started out at Harvard as an English major, but you changed to history midway. How did that come about?

I took an exam in a modern English course. I can’t remember the course now, and there was a three-part question — this is my sophomore year — a three-part question. A: I read the novel of A. I had not read the novel of B, and I had read the novel in C. But I had enough of the New Criticism jargon in my head — the criticism of that time was called New Criticism — so that I was able to fake my way, fake my ignorance of Novel B, and I got an A in the course. I got an A in Levin’s course and only went to two of his classes. I wrote my papers and handed them in, but I only went to two lectures. I decided this is no good. I’m not learning anything.

I should switch to history, because I liked history, and I always read history. In fact, before I had gone to boys’ school, one of my escapes, when I was unhappy, was to read historical novels. History had always appealed to me. I had a grand uncle who was an Irishman of his generation, in the sense that the British empire was his great enemy. The Germans had not sunk the Lusitania in World War I; the British Secret Service had. He was a great history buff, and I’d go to his house for my lunches when I was a little boy in grammar school, and we’d talk history after lunch, and so I had this love of history. I said, “What form of history should I major in?”

I had an Iranian roommate who has since disappeared. I don’t know what happened to him. He went back to Iran, and he disappeared. He was a very wealthy, very decadent character. He majored in architecture and never did any studying. He hired an Iranian graduate student to write all of his papers for him. The professors thought Reza was brilliant and always wanted to discuss his papers with him, which he never would do because he didn’t know anything about what was going on in the course.

Harvard had just formed a new Middle East center. The old Aga Khan gave Harvard a lot of money to form a Middle East center, and Harvard went to Oxford University to hire the premier Arabist of his time. It was a man named Sir Hamilton Gibb, and they, in effect, bribed him out of Oxford. They said, “Look, we will make you a University Professor, which means you can do whatever you want. Here is all of this money if you found a Middle East center. Hire whoever you want to. Your decisions are entirely yours. Please come,” and he did. He left Oxford and came over, and he started this Middle East center. It started the year before my freshman year.

I switched to Middle Eastern history. I thought, “Hey, this would be interesting to do,” and it was wonderful. His lectures were grand. I had a very good tutor. I took the honors course. I wrote a thesis on something they called the Wafd Party, which was one of the early nationalist parties in Egypt, which was corrupted by the British. I remember one of the professors who read it said it was too generalistic, that was the criticism of the thesis. But I did get honors, regular honors, cum laude, not high honors because I was still drinking then, and it was interfering with my courses, but it was a wonderful decision to major in it. I have never been to the Middle East, except as a tourist, but I learned things. Studying Ottoman history was fascinating. I learned things about a part of the world I knew nothing about, and I’ve followed it ever since. I’ve followed it from afar ever since. I read constantly, anything about the Middle East.

So I got out of Harvard, graduated. We had military service then. You had to do six months and then five years of reserve, or you did two years through the draft. They were still calling up the reserves then. It’s forgotten now, but Kennedy called it the “reserves over Berlin.” I didn’t want five years of reserve duty hanging over me. I went to the draft board in Holyoke, my hometown. I volunteered for the draft, and they said, “You’ll have to wait six months.” I said, “Why should I have to wait six months?” They said, “The Army is only taking two a month.” There was no war on. The Army was much smaller than it is now, and so I went to the recruiting sergeant. He said if I joined for three years, I’d get a much better deal. I ended up as a pay clerk in Korea up by the Demilitarized Zone in a miserable place. It was really miserable. The windows in the old Quonset huts were broken, and we froze to death in the winter. You’d have to get in your sleeping bag to sleep at night. It was horrible.

I got word that they were looking for writers in the Division Information Office, 40 miles closer to Seoul. So I went down there, and I took the test. The Army has a test for everything. I took the test for journalism, and I passed it. The sergeant who was running it knew nothing about how to run an information office — he couldn’t write a sentence — but he knew that you hired a PFC who could. He offered me a job, and the sergeant I was working for in this miserable place up by the DMZ let me go. So I went down there, and I ended up running the Division Information Office. My deputy was another PFC named Bernie Weinraub, who ended up as the New York Times reporter in Hollywood, and accompanied me on his last assignment in Korea. He was in Vietnam, too. I discovered I really liked this, and then…

They offered me a job to go over into Tokyo to put out a weekly. We put out a weekly newspaper for the division, and they offered me the job of going to Tokyo because the sergeant who was there was going home, and they offered me the job of going over there and taking it over, and I took it. I jumped at it. So here I was in Tokyo, working at Stars and Stripes, putting out a weekly newspaper. We worked in civilian clothes, except once a month we had to put a uniform on. We were living in officers quarters in what later became the Olympic Village. The Japanese had built it during the occupation. And I decided I really like this. I want to be a journalist. I want to be a reporter. This is what I want to do, and I hadn’t known that when I joined the Army. I thought I’d go to work for the CIA and study Arabic or something, and go to work for the CIA or some oil company or something like that, but journalism is what really turned me on.

Part of my job was to hand out a news release to the real press in Tokyo if something happened to our division in Korea that was newsworthy. So I got to know the guys in the AP Bureau and the UPI Bureau — UPI then was a very lively wire service — The New York Times guy and The Wall Street Journal guy and the Newsweek guy. When I went to the AP, it was very well staffed. The Associated Press is an association of newspapers. It doesn’t have to make a profit, and the UPI, which is a privately owned wire service, was understaffed, critically understaffed. They had nobody in there. They had one American reporter and one Japanese reporter on duty. Teletype machines banging, making a terrific racket — these old World War II things that they had taken the covers off of — which they were sending and receiving on. When I went in there with a news release, the American guy would say, “Throw it on the table, kid.” He had no time to talk to me. So…

I thought, “Well, if I go to the AP, I’ll never get anything to do, but if I go down to the UPI and ask them if I can work for nothing to learn the business…” because I realized you got to go to a professional to really learn this business, “…maybe they’ll let me do it.” So I went down, and I asked the bureau chief if I could work for nothing. He said, “You want to work for nothing, kid?” I said, “Yeah.” He said, “When do you want to start?” I said, “Could I come in three days next week: Monday, Wednesday, Friday?” He said, “Sure. Come in. Come down at three o’clock,” because I finished my work editing the paper by 2:00, and I could catch the train into Tokyo.

He said, “Come in for the 3:00-to-11:00 shift.” So I came in, and I was sort of an assistant to the guy who was pulling the shift, because there was only one American reporter and one Japanese reporter on each shift. Tokyo was a filing point for Asia. Everything came pouring into Tokyo in cable-ese to save money. You didn’t put “the’s” in. It was all shorthand. Then you rewrote it into readable English and sent it on the wire to San Francisco via Manila. In any case, I came in. I worked for two weeks, three nights a week, and then they said to me, “How would you like to pull a shift by yourself, six nights a week? We’ll pay you ten dollars a night.” So I called my boss in Korea, a major who was the information officer for the division, and I said, “Can I do this?” He said, “Yeah, sure. Just no bylines. There is no Army regulation against it. Just no bylines, because you’d be accused of bringing disgrace on the Army if something happened. But otherwise, go ahead.” So I worked for them for about five or six months, my last five or six months in the Army, and then they offered me a job. I took my discharge in Tokyo. I went to work for them for a very simple reason. The turnover was tremendous. I knew that I’d get out of Tokyo and I’d get a bureau very quickly, because people were constantly turning over.

The guy in Jakarta, Indonesia, for instance. I got a message one night for the boss, whose name was Ernest Hoberecht, the vice president for Asia. It said that the guy — I’ll never forget his name, it was Dabovich — he cabled up, and he said his draft board had notified him. He had to come back for the draft, and he’d be leaving. So I called Mr. Hoberecht at home and read him the telegram, and he said, “Fine. Take a message,” and I took the message. The message said, “Okay, Dabovich. Don’t worry about it. Just leave when you have to. We will replace you.” So a couple of nights later, a message came in, and it said, “What about my plane fare home, Ernie?” and I called Mr. Hoberecht at his home, and I read that to him, and he said, “Take a message,” and the message said, “Dabovich, if your draft board wants you, they can pay your way home. Hoberecht.” His salary was partially based on the percentage of profit that the division made. So every nickel Hoberecht spent was coming out of his own pocket. Well, about three nights later, a very angry message came in from the President of UPI in New York saying, “Hoberecht, damn it, give the kid his money so he can go home.” I did not call Mr. Hoberecht at home and read him that. UPI was underpaid. It was undermanned. People called it the “Marine Corps of Journalism,” and there was this tremendous turnover. So I went to work for them in April of ’62 when I got out of the Army.

You were in Japan when you got out of the Army and went to work for the Associated Press. How did you end up in Vietnam?

I took my discharge in Japan. A month later, I found a note in my typewriter saying, “How is your French? Come and see me in the morning.” It was from Hoberecht, the boss, and he told me that the guy who had broken me in, who had trained me for the desk and who had gone down to Saigon, had just quit and gone to work for Time magazine as their stringer. They paid him a lot more than UPI was paying. How would I like to go down there? “Oh,” I said, “I’d love to go down there.” I was the logical choice. I was the bachelor in the office. So down I went. I was in Vietnam a month after getting out of the Army. I never got shot at in uniform, but (I got) shot at after I got out. And that’s where it started. That was my first assignment. I spent two years there for the UPI, ’62 through to ’64, which was the “advisory war,” the Kennedy war — the helicopters and the military advisors — and that failed, of course. The Viet Cong kept getting stronger and stronger.

I went back in ’64 and got a job at The New York Times and met my wife, who was a staff writer for The New Yorker, and after my six-month probation period on the Times was over — the Times had a probationary system for your first six months. You could get sacked without any justification. They could just say, “Thank you very much, but it won’t work.” But after six months, you were permanently on hire. When my six months was up, the foreign editor called me over and said he wanted me to go down to Indonesia as fast as I could, take the bureau there. So I went down there, and I was there six months. They sent me up to Vietnam for our third year in Vietnam. A friend of mine was taking over the Vietnam job, and he wanted me to work with him. So I spent two years in Vietnam for the UPI and then a year there for The New York Times, and then I came back. They sent me back to Washington to be a Pentagon correspondent. So I never got away from the war for ten years.

When you started out as a reporter, did you ever imagine that Vietnam would become so much a part of your life?

Neil Sheehan: No. It never occurred to me. It was all — how do you say? — serendipitous. I took this job with the UPI because I wanted to be a reporter. I wanted to be a journalist. You got responsibility right away at the UPI because there was nobody else to do it. That’s why they offered me a job, six nights a week at $10 a night. I learned how to run a desk. I mean, somebody broke me in and taught me, but I learned how to run a desk, a wire desk, a war service desk, where copy just poured in and you had to rewrite it. You also had to cover Japan by telephone if anything happened. Then they sent me down to Saigon because somebody quit, and I was thrilled to go. I mean, to go down and to cover a war, wow! That was the big story, and you weren’t afraid at first, you know.

Later on, I interviewed somebody who had barely survived the first Chinese assault in Korea. He got out of West Point and went to Korea as a second lieutenant, and they put him to work organizing this ranger company out of cooks and bakers. He couldn’t take any regular infantrymen. All he could take was rejects, cooks, bakers, people like that in Japan, and they turned out to be a wonderful fighting force, although they didn’t survive long with the Chinese. His company was one of the first units assaulted in 1950 in Korea when the Chinese broke loose in the north. He was badly wounded in his legs, and his men were so loyal to him, they came back up the hill after the Chinese had overrun it and pulled him out of the foxhole and dragged him off the hill. And I asked him, “Were you afraid?” He said no. He said, “I wasn’t afraid to go.” He said, “Hell, I thought it was like going to a football game. I was just afraid I was going to get there, and the game would be over. I’d get there too late.” Well, it was that attitude I had going to Vietnam as a young reporter.

I wasn’t afraid going to war. I almost got killed six months later in a so-called “friendly” artillery barrage. This incompetent Vietnamese general shelled his own troops. That put the fear of God into me. From that day forward, I was always afraid when I went out, but you had to go out. You just had to learn how to control your fear. That’s all. Soldiers — most soldiers who are sane — are afraid, but they control. The professionals learn to control their fear, and that is what you had to do, because you had to go out.

How do you see the journalist’s role in American society?

Neil Sheehan: We have a unique law in this country called the First Amendment of the Constitution. It says that Congress shall pass no law abridging freedom of speech, respecting establishment of religion, or abridging the freedom of the press. I have always believed that that places a duty on the American journalist to seek out important truths and to get those truths to the public. Now, what’s important varies according to the time, but you’ve got to think of yourself — you’re not an ally of government. You are not a propagandist. You are not an advocate. You are a witness, and you’ve got to find out the truth of a given situation and then get that truth into print or on television or on the air — however. That is what an American journalist should do, because I think, in this country, journalism is really a fourth branch of government. It always functioned as a fourth branch of government.

The most recent example of it is Watergate. We need a system of checks and balances. We are not like the Brits. We don’t have a sense of restraint.

The Founding Fathers built in a sense of checks and balances with the three branches of government, and they also, I think, meant there to be a fourth branch, which is the press. That’s why they enacted that law, the First Amendment. It’s the First Amendment to the Constitution, not the Second, which is to carry firearms, but the First. And it’s there for a reason, I think, because they saw the press as a check on government, on the power of government, and it’s terribly important that journalists remember that, publishers remember it.

The most recent example is this terrible business in Iraq. Look at how much of the news media went along with Iraq. You saw Fox News. You’d turn on Fox News, here was this headline — this caption — that said “Operation Iraqi Freedom,” which was the Pentagon slogan for the invasion of Iraq. It was a catastrophe, that war, and you could have foreseen it was a catastrophe, and the news media should have been hammering home early on, what the possibilities were once these people were opening up, because Iraq was never a country. It was put together by the British for the oil out of three Turkish provinces, none of which had anything to do with each other. None of this got before the American public. You had press barons like Murdoch who were pushing the administration’s point of view, and if you didn’t broadcast what Rupert Murdoch wanted or print what he wanted, he’d sack you.

It was the same thing in the old days with Time magazine. If you didn’t turn in what they wanted, they just tore it up and threw it in the wastebasket.

My friend, as I said, Charles Mohr, who worked for the Times, he quit Time magazine for that reason. They asked him to write a story on whether the commanding general and the ambassador were right, or whether the reporters were right, and this is the early period in Vietnam, when we were in the clash of whether we were winning or losing the war. Charley wrote them a story — he was their Southeast Asia bureau chief — the first sentence in his report, because he showed it to me, was “The war in Vietnam is being lost.” They tore it up and threw it in the wastebasket and concocted out a whole clause, a story in New York, saying that we were making up our stories in the Caravel Hotel bar in Saigon, and Charley resigned over it.

This is the opposite of what American journalism ought to be. American journalists ought to be honest, independent and adversarial journalists. Journalists don’t have any friends in government. One of my editors once said to me, “If you get invited to the White House, take your notebook with you,” and he meant it. It’s something one has to always remember because when you stray off the path, you do a disservice to the American public.

Are there lessons to be learned from Vietnam in American foreign policy today, for American journalism today?

Neil Sheehan: Sadly, I don’t think the American nation has absorbed the experience of Vietnam. They haven’t processed it. They haven’t come to grips with it. If they had, we wouldn’t have gone into Iraq.

The central lesson of Vietnam is the United States can do evil as easily as it can do good. Now that is something that grates on most Americans. They think America is an exception to history, that the United States can never do anything wrong, that what we want, the rest of the world ought to want and that they do really want it. Well, that is not necessarily true. So the lesson of Vietnam is: before you go out to do violence to other people and violence to your own young, your own people, you ought to be absolutely certain that you have to do it. You don’t pick a war. Iraq was called a “war of choice.” You don’t start wars of choice. I mean, you start a war that you absolutely have to. If you go to war, you absolutely have to, and we didn’t have to go to war in Vietnam.

We thought we did. There was more of a justification, from a moral point of view, for Lyndon Johnson and Robert McNamara, who were also products of the Cold War, to have gone to war in Vietnam than there was for the Bush administration to have gone into Iraq.

I think one of the main reasons why they did go to war in Iraq was because they all dodged the war in Vietnam. The President escaped into the Texas National Guard. The Vice President got, I think, five draft deferments. The Secretary of Defense, Rumsfeld, was a Navy pilot, but he didn’t fly during the war. I think he flew before the war, so he had no experience in Vietnam. The great intellectual hawk, Wolfowitz, also escaped on draft deferments. Perle, another big hawk who helped push us into it, escaped in a draft deferment. You look at these guys, none of them had any experience in Vietnam.

If you came to me — and Colin Powell was the only one who did — and I think Powell made a terrible mistake when he bought that intelligence and went up and made that speech at the UN, a terrible mistake. He ruined himself, because even if that intelligence was true, it was still no justification to go to war. Weapons of mass destruction indeed! You know, both sides in World War II had gas, and neither of them used it. The Germans invented nerve gas. It was by accident when they were developing insecticides. They didn’t use it because it’s not very useful on the battlefield. The wind changes, and it comes back on your own people. Sure, you can kill a lot of poor Kurdish villagers who can’t get away, but you use it against an army, they’ve got equipment. They get in these rubber suits, and they get through it, and then they kill you. Even if Saddam Hussein was developing a bomb, it was still no reason to go to war against him. There were other ways to deal with it. Israel has dozens of nuclear weapons. Are we going to war with Israel because they have dozens of nuclear weapons? None of it made sense to me.

If you had come to people who had experience with Vietnam, who were seared by Vietnam, who had absorbed the whole experience of Vietnam — that it was a terrible mistake, that the Vietnamese were not our enemies, that we killed a million Vietnamese, at least, for no good reason, and lost 58,259 of our own people — they’d have said, “Are you crazy? I need you like I need a social disease,” which is a polite expression of an old military term. That would have been the end of it. “Get out of the room. Find some other way to deal with this character, but we are not going to stick our hand in a hornet’s nest like Iraq and get thousands of our own people killed.” A small number, but tens of thousands of the peoples of Iraq, and probably many more will die when we leave there, and we are going to have to get out. So that ends what I have to say about it.

If young people come to you today and say, “Mr. Sheehan, I would like to do what you did. I would like to follow in your footsteps,” what would be your advice to them?

Neil Sheehan: My advice would be to try to find a television station or a newspaper where they are going to get some good basic experience in their craft, because you need that. And then try to get yourself assigned to the biggest story you can get, even if it’s dangerous, no matter what it is, a story that is going to get attention, where you are going to get attention. We were lucky in Vietnam, as journalists, in the sense that we could fulfill ourselves by printing the truth, and also, we got attention from other editors. They read your copy coming in over the wire. In those days, it was the wire, the foreign editors. So we got attention within the profession. So that would be my advice. Learn your craft, and then find the toughest story you can find, whether it be in this country or overseas. You got to, because that’s the only way you can really get ahead in the profession. It’s very competitive, and the way you get ahead is by getting the attention of people who are going to hire you, who see that you can perform in difficult situations. People hire known quantities. Organizations hire known quantities. They want to know, if they hire someone, “Will he perform?” or “Will she perform?” So that would be my advice to them.

You’ve written about some major failures of American leadership, in Vietnam and elsewhere. We’ve been more fortunate on other occasions. Who do you think were truly successful leaders in American history?

Neil Sheehan: I’ve read a good deal of Civil War history, and we were very fortunate in President Lincoln. This country was very fortunate in three or four major occasions. We were very fortunate in George Washington during our revolution. He was a wise leader, and he turned out to be an able general. We were very fortunate in President Lincoln because he was such a wise leader. He knew what to do at the right time. He was a very shrewd politician, and he knew that he had to get a really good general to destroy Lee’s army, which was the key to destroying the Confederacy. When you destroyed Lee’s army, you destroyed the Confederacy, and he understood that he was running out of time, so he appointed Grant, who is one of the great generals in our history. He knew when to issue the Emancipation Proclamation and when to withhold it. He knew when to threaten the British, who were trying to break us apart by building warships for the Confederacy. Our big enemy then was Britain, and also France that had gone into Mexico. He knew when not to move and then when to move against them.

And then we were very lucky during the Depression with Franklin Roosevelt, who probably saved this country from a revolution. And then, during World War II, Roosevelt appointed the right man to lead us, General Marshall, really a very wise decision. Once he had Marshall in the saddle, Marshall knew who to reach for.

As a writer, what do you think about Lincoln’s words?

Neil Sheehan: They’re extraordinary. I won the Gettysburg Address Prize when I was in boys’ school for reciting the Gettysburg Address. I think it’s one of the great pieces of American writing because it’s so moving. Lincoln had a wonderful economy of words. He did not write or say too much, even in his short rejoinders. Supposedly a group of congressmen came to him, and they wanted Grant fired. I don’t know if it was over the drinking or what. They had their reasoning. They wanted Grant fired, and Lincoln said, “I’m sorry I can’t oblige you gentlemen. I can’t part with that man. He fights.” End of argument, very succinctly put. And in his notes, he’s eloquent, but he’s also very succinct, and it’s beautiful to read, to read things like the Gettysburg Address. You never get tired of reading them. You go up to that monument which is really a Greek temple to a demigod, which in our history he became, and you read those words, and they are never stale. That’s the real secret, I think, to a man who is a great public figure, and also a great writer as Lincoln was.

We don’t want to, but we have to let you go. Thank you so much.

Neil Sheehan: You’re welcome.