If Jesus Christ were alive today, He would be attending the Super Bowl.

Alvin Ray Rozelle was born in South Gate, California, and grew up in neighboring Lynwood, suburban communities southeast of Los Angeles. He was nicknamed “Pete” by a favorite uncle, who, like his father, encouraged his interest in sports and the outdoors. He played basketball and tennis at Compton High School and served as sports editor of his school’s paper, as well as working weekends at the Long Beach Press-Telegram newspaper. After serving in the U.S. Navy during World War II, he returned to the Los Angeles area, and enrolled at Compton Junior College. The Cleveland Rams football team, newly relocated to Los Angeles, practiced at Compton, and Rozelle worked part-time for the team’s publicity department, where he caught the eye of Rams executive Tex Schramm.

Rozelle transferred from Compton to the University of San Francisco, where he worked as a publicist for the college football team. As an undergraduate athletic news director, he drew national attention to the school’s victory in the 1949 collegiate basketball tournament. He remained at the university after graduation, serving as athletic news director and assistant director of the school’s sports programs. In 1952, his previous employer Tex Schramm offered him the job of publicity director for the Los Angeles Rams, and he began his life’s work of building American professional football into the country’s most popular spectator sport. After a year’s interlude with an L.A.-based public relations firm, promoting the 1956 Melbourne Olympics, Rozelle returned to the Rams organization and was soon promoted to general manager. In the next three years, he demonstrated his notable flair for showmanship and spectacle and turned the struggling franchise into a highly successful enterprise.

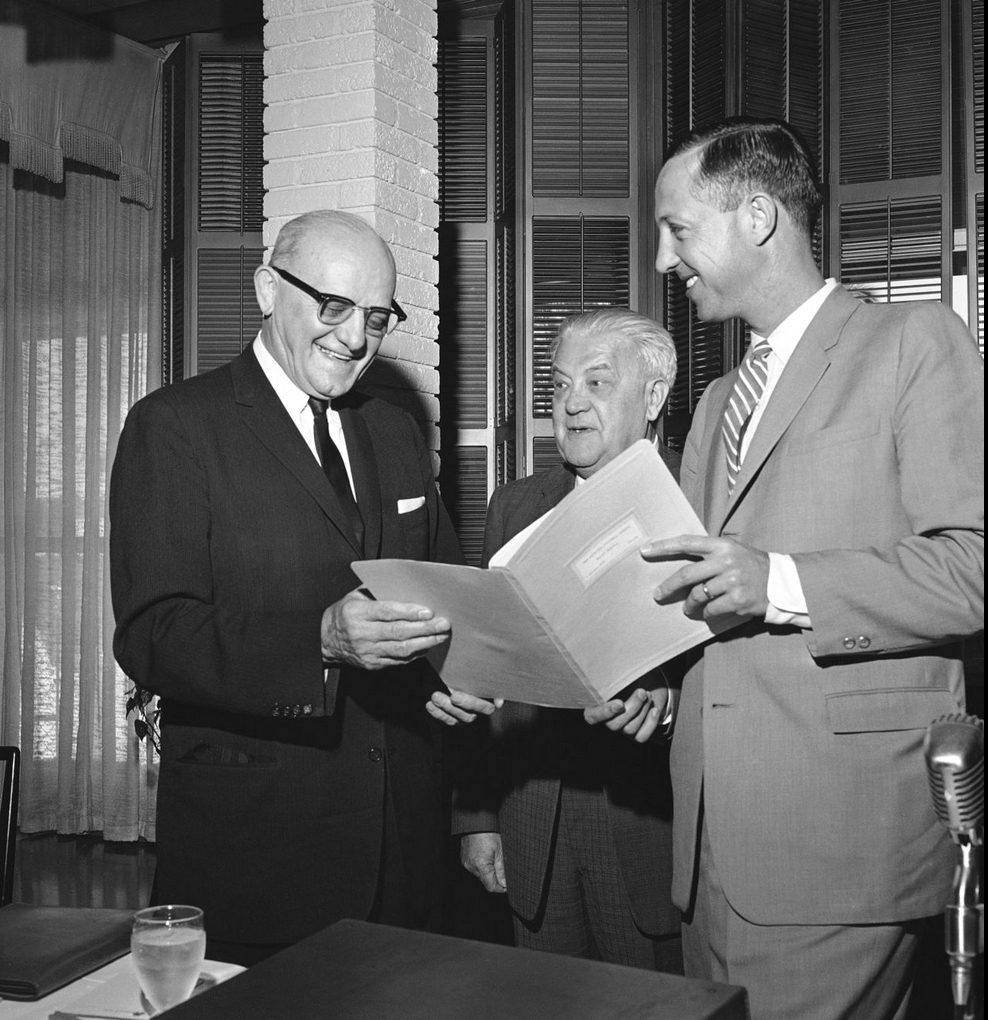

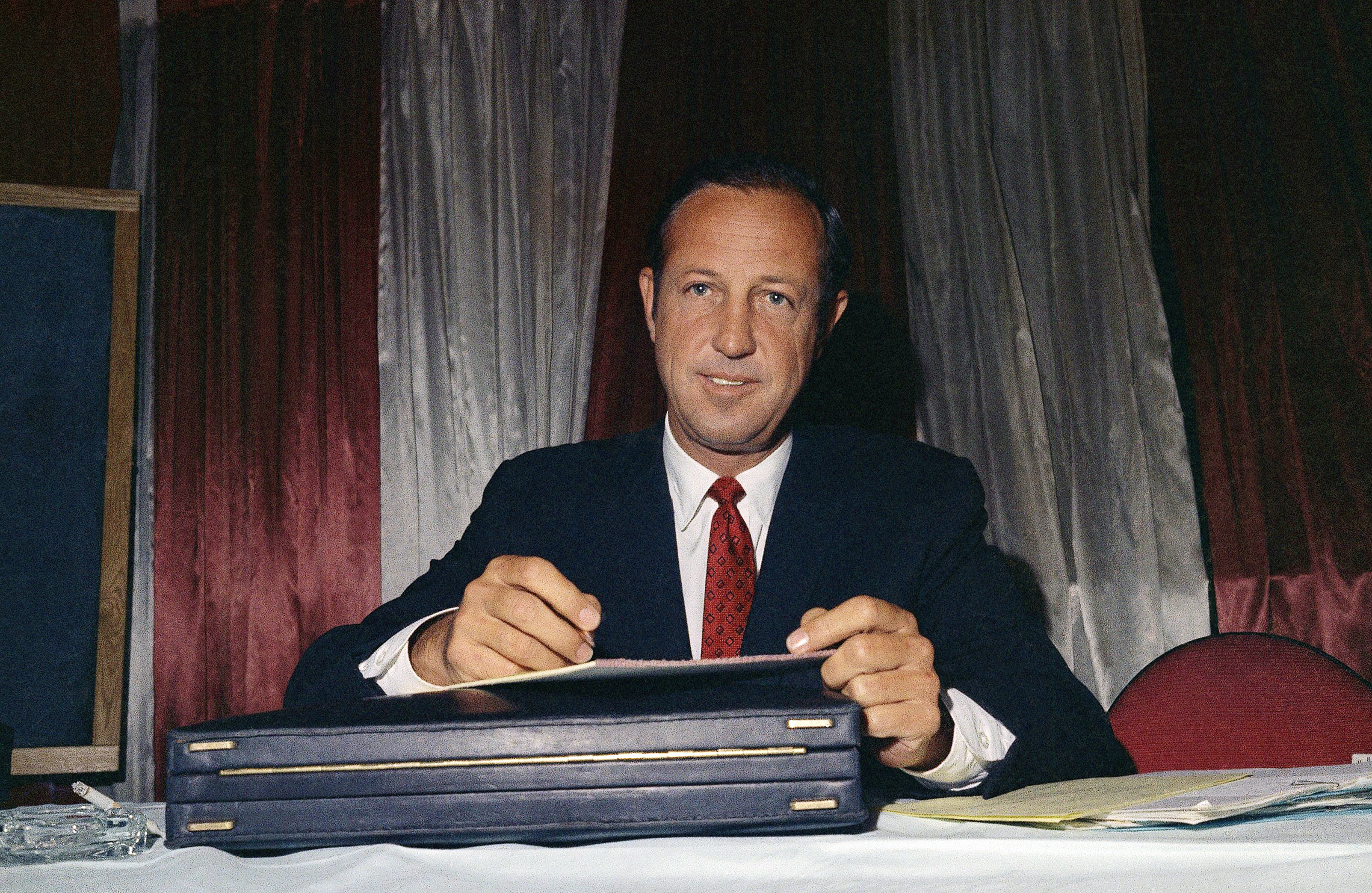

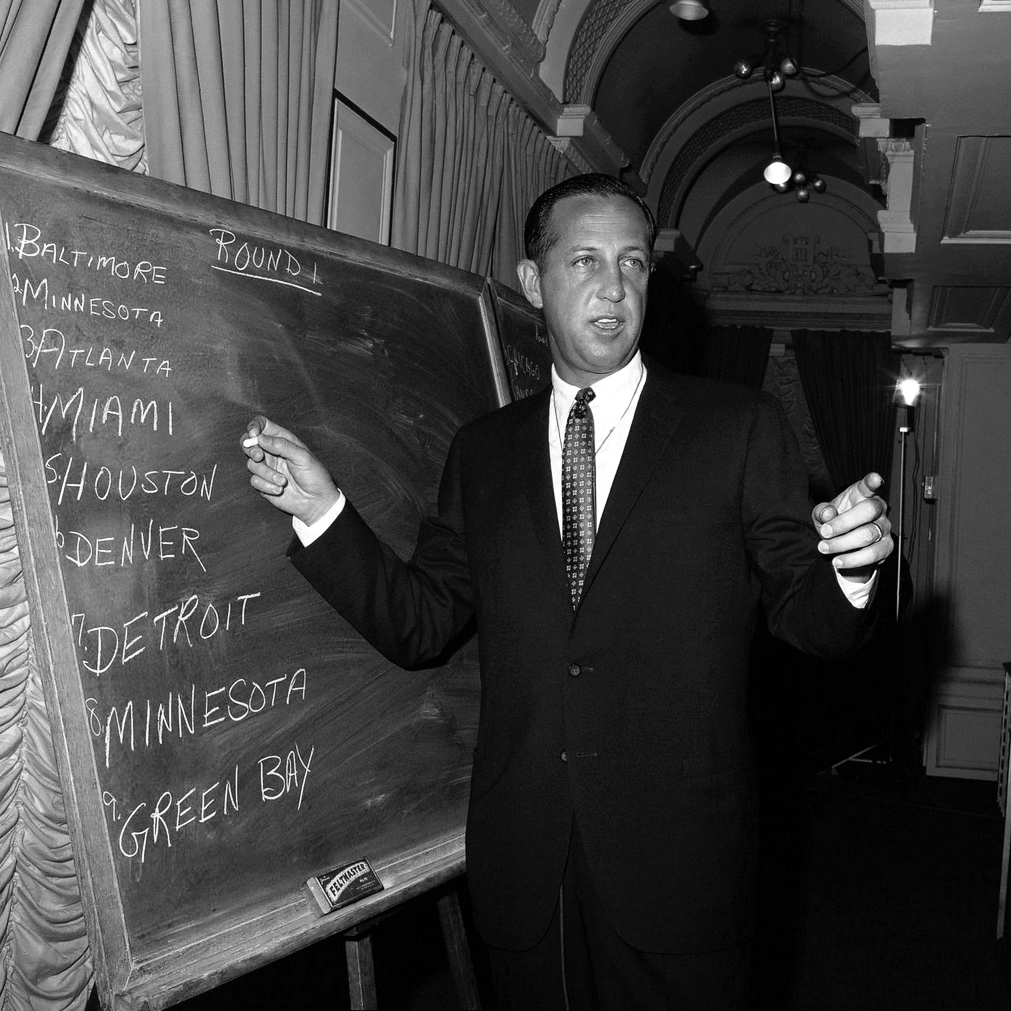

When the longtime commissioner of the National Football League, Bert Bell, died suddenly in 1959, the team owners found themselves deadlocked over the choice of a replacement. After 23 ballots, they settled on a surprise choice, Pete Rozelle. At age 33, Rozelle was less well-known and less experienced than the two other candidates, and there was speculation that he had been chosen because the owners imagined that he could be easily manipulated, but this soon proved not to be the case. It was assumed that the role of commissioner was to moderate disputes between owners and serve as a bureaucratic spokesman for the sport, but Rozelle embraced a larger mission: building the wealth and prestige of professional football as an industry. When he assumed the post in January 1960, there were barely a dozen teams in the league, playing poorly attended games, mostly un-televised. A few of the owners had individually negotiated broadcast rights for their teams’ games, but the franchises in smaller markets languished in unprofitable obscurity. Team owners were wary of expanding the league, fearful they would saturate the market.

Meanwhile, Texas multimillionaire Lamar Hunt had started a rival organization, the American Football League (AFL) and was aggressively competing for talent with the older league by bidding up players’ salaries. Rozelle succeeded in adding two franchises to the league in his first year, blocking AFL expansion in those markets, but he believed the future of the game lay in expanding its national television audience. He moved the NFL offices from Philadelphia to New York, home of the three major television networks, and began aggressively pursuing broadcast deals. The most profitable arrangement, he knew, would be to give a single network the broadcast rights to the games of the entire league, rather than allowing the larger franchises to negotiate their own deals with different networks. Rozelle’s plan faced significant regulatory hurdles, stemming from the Sherman Antitrust Act, the federal law restricting monopolies.

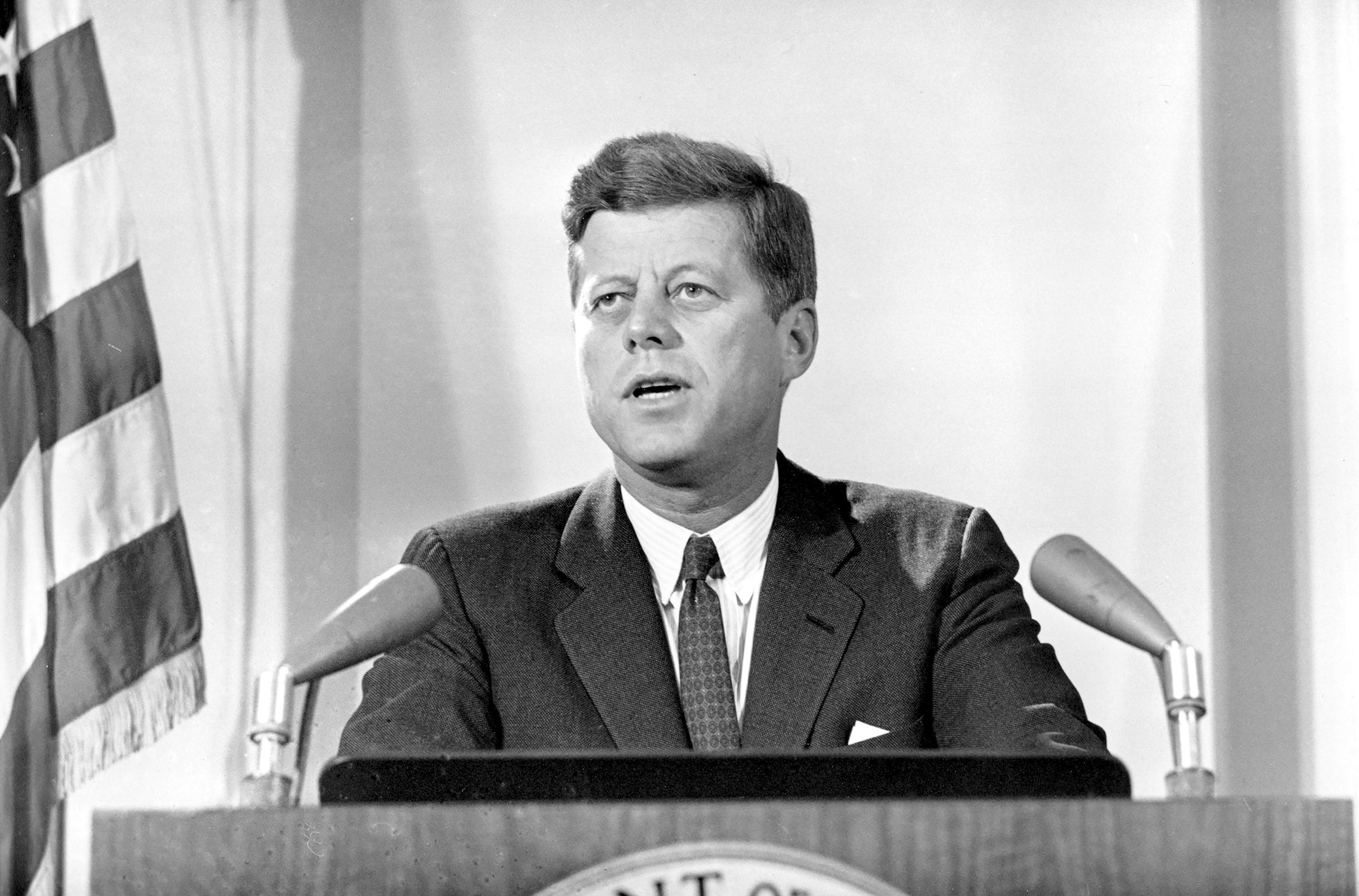

After intensive lobbying by Rozelle, Congress enacted legislation, signed by President John F. Kennedy, permitting sports leagues to negotiate contracts directly with the broadcast networks. By 1962, Rozelle had secured a two-year contract with CBS for network broadcast of the entire NFL season, with revenues to be shared equally by all the teams. The team owners were strong-willed entrepreneurs, used to charting their own courses, but Rozelle persuaded them to embrace the revenue-sharing concept, minimizing inequalities between the teams and making the entire league more stable and more competitive.

At the same time, Rozelle had to cope with an antitrust lawsuit brought against the league by Lamar Hunt’s AFL. The federal courts dismissed the AFL suit in 1962, but friction between the rival associations continued. Rozelle encountered controversy early in his tenure as commissioner. Rumors of players’ involvement in gambling threatened the game’s public image. Early in 1963, Rozelle suspended players Paul Hornung and Alex Karras for betting on games. Rozelle’s measures were applauded, but worse difficulties lay ahead.

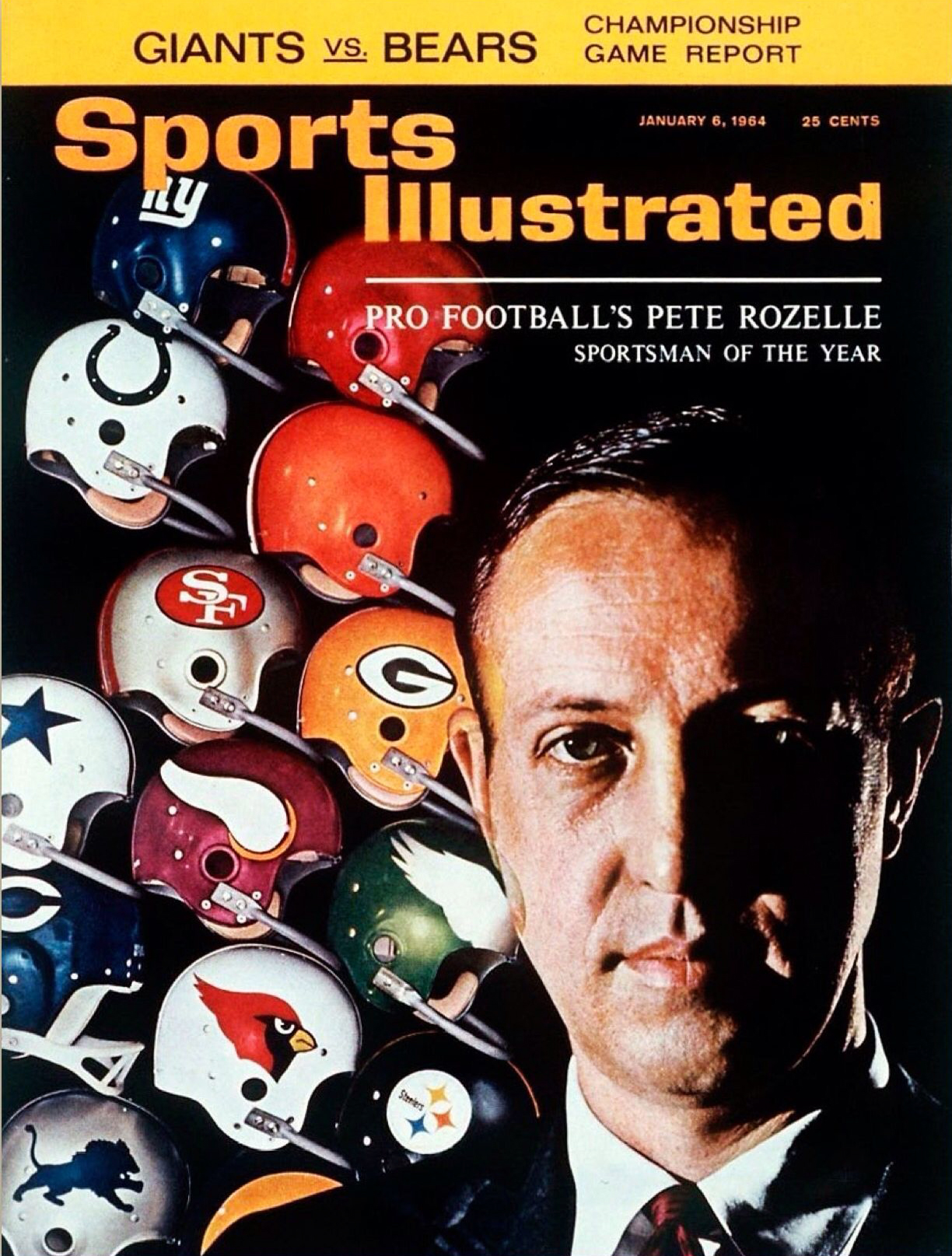

When President Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963, Rozelle had to decide whether to proceed with the season, with only two days between the murder of the president and the next scheduled game. After consulting with White House Press Secretary Pierre Salinger, a friend from San Francisco college days, Rozelle elected to proceed with the games. He felt it would set a good example for a nation persevering in the face of loss, but all broadcasts were preempted for news coverage of the assassination and its aftermath, and Rozelle was subjected to harsh criticism. Nevertheless, his ability to mediate the squabbles of contentious franchise owners won him the respect of the national sports press, and he was selected as 1963 “Sportsman of the Year” by Sports Illustrated magazine.

In the mid-’60s, the competition for players between the two professional football leagues intensified. After poaching the NFL’s college draft picks, the AFL began hiring players away from the older league. The bidding war spurred a drastic inflation in players’ salaries, and owners in both leagues realized the situation was potentially ruinous.

Rozelle undertook the most difficult challenge of his career, negotiating a merger of the two rival leagues. After reaching an agreement with the assorted team owners, Rozelle still had a significant regulatory obstacle. The television networks in particular dreaded bargaining for broadcasting rights with a single unified professional football league. In his testimony before the House Judiciary Committee, Rozelle assured lawmakers the merger would preserve the existing franchises and continue to generate revenue for the host cities. Congress granted professional football an exemption from the Sherman Antitrust Act.

A merger of the leagues was agreed to in 1966, with Pete Rozelle serving as commissioner of the combined organization, although the realignment of professional football into American and National Conferences within a single national football league was not fully completed until 1970. Rozelle also persuaded the team owners to abide by a single draft process that would allow the lowest-ranked teams the first choice of newly available college players. This raised the overall standard of play throughout the league, drawing increased attendance for all teams, and a rapidly increasing television viewership.

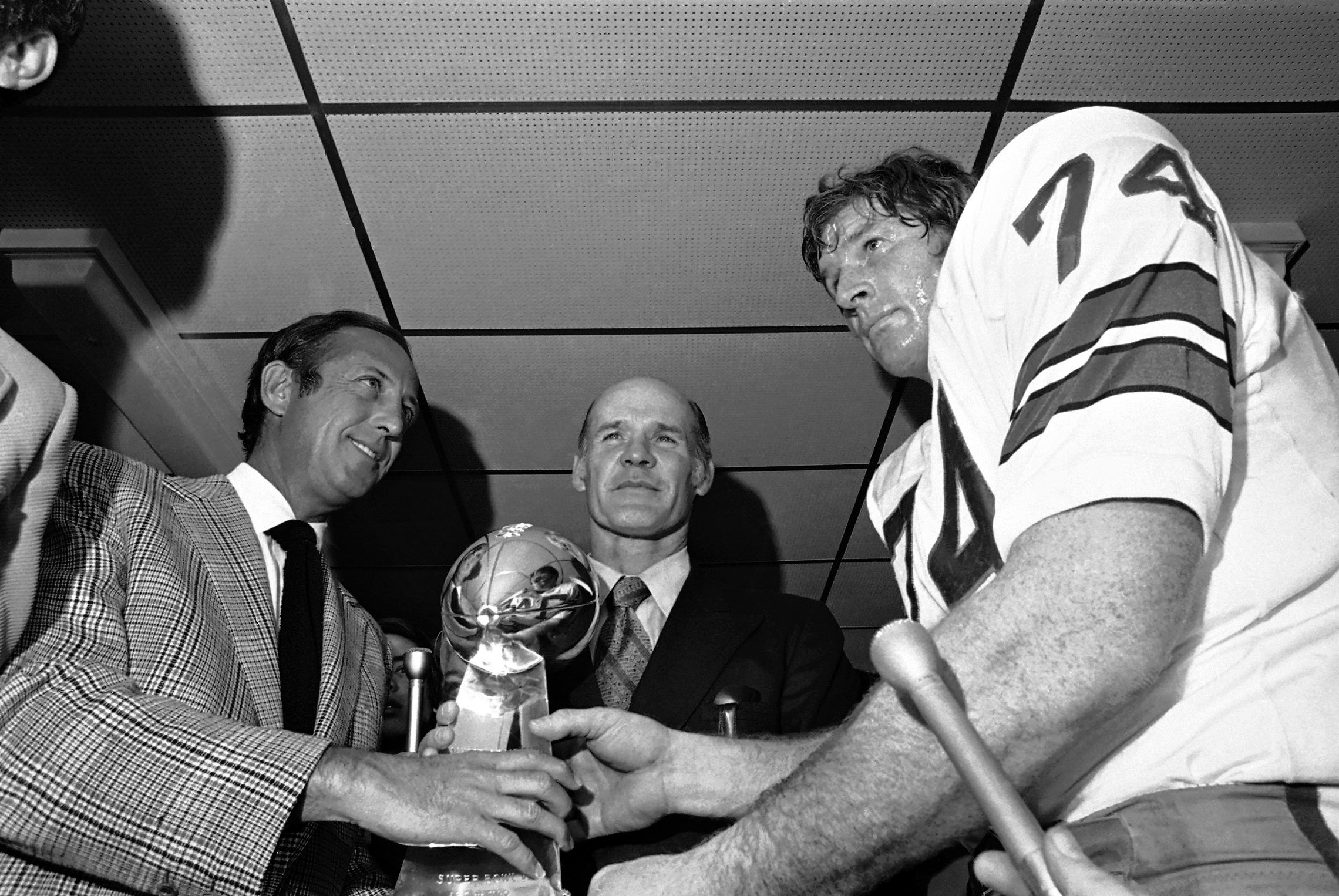

The 1960s were years of explosive growth for professional football, as Rozelle presided over the introduction of a post-season championship game, the Super Bowl. Although the first Super Bowl game, in January 1967, was played to a nearly half-empty stadium, Rozelle arranged for the game to be broadcast simultaneously on both NBC and CBS, forcing two networks to compete in promoting their coverage of the event. Within a few years, the annual game had become a national institution, the most-watched television event of the year. The upset victory of the New York Jets in Super Bowl III brought unprecedented publicity to professional football. As concerned as ever with the image of the game, Rozelle threatened to suspend the winning Jets quarterback, Joe Namath, if the star player did not sell his interest in a nightclub frequented by professional gamblers. Namath retired rather than face suspension, but within six weeks had returned to his team on Rozelle’s terms. With the growing popularity of televised football on Sunday afternoons, Rozelle engineered the introduction in 1970 of Monday Night Football, a weekly television event that has become a wintertime obsession for many Americans, and is the longest-running non-news program on prime-time television.

In 1974, Rozelle had to deal with a preseason work stoppage by the players’ union. The dispute was resolved before the season began, but professional football’s labor troubles were far from over. For the first time since the AFL-NFL merger, Rozelle had to contend with a rival association, the start-up World Football League. The new league lasted little more than a year, but it reignited the inflation in players’ salaries that the merger had squelched. Rozelle had secured his league’s exemption for the antitrust law by assuring Congress that the teams would stay put in their respective markets, but team owners began to demand that host cities build larger and larger stadiums with more and more amenities. When cities balked, a number of owners attempted to move their franchises elsewhere.

Rozelle was able to prevent a number of these relocations, but he lost a bitter court case with Oakland Raiders owner Al Davis, who moved his team from Oakland to Los Angeles, and then back again, antagonizing fans and civic leaders in both cities. The 1980s brought another challenge to the NFL’s domination of professional football with the emergence of the United States Football League. The USFL lasted three seasons, 1983-85, notable mainly for the performances of running back Herschel Walker, who enjoyed a subsequent career with the NFL. Pete Rozelle was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1985. The following year, the federal courts handed Rozelle a stunning victory. The failing U.S. Football League had filed a $1.6 billion antitrust suit against the NFL. The court awarded them exactly three dollars, and the USFL quickly disappeared. A greater threat to the NFL arose in 1987, when the players’ union struck in mid-season. After losing a week of games, Rozelle made the difficult decision to bring in replacement players, and kept the season running for another three weeks until the players and the owners came to terms. When his contract with the league expired two years later, Rozelle stepped down as commissioner. In nearly three decades at the helm, he had seen the league grow to 28 teams. Rozelle’s genius for promotion had driven a massive increase in the game’s audience, until it eclipsed the former national pastime, baseball, in popularity. Regular season football games now routinely draw larger television audiences than the playoff games of other sports.

For the last seven years of his life, Pete Rozelle continued to advise the NFL from his home in Rancho Santa Fe, California. He succumbed to a brain tumor at the age of 70. He was survived by his wife, Carrie, and by a daughter from a previous marriage. In his lifetime, Pete Rozelle’s contribution to the growth of the NFL went nearly unnoticed in a milieu crowded with outsized personalities, but with the passing of the years, it has become increasingly apparent that he did more than anyone to develop professional football into the powerful force in American popular culture that we know today. In 1998, Rozelle was listed as one of Time magazine’s “most influential business geniuses” of the 20th century, along with several other American Academy of Achievement members, including Bill Gates, Ray Kroc, Akio Morita and Stephen D. Bechtel. In 2000, Time magazine named him one of the 100 most important people of the 20th century.

When 33-year-old Pete Rozelle was selected by team owners to serve as Commissioner of the National Football League, the NFL was a loosely organized collection of scattered franchises, many playing to half-empty stadiums, each negotiating its own television broadcasting contracts. It lagged far behind baseball in popularity, and what little cohesion the league enjoyed was threatened by the newly organized American Football League, a virtual millionaire’s club with a more aggressively coherent strategy toward broadcasting and promotion.

In his first years as commissioner, Rozelle secured crucial antitrust exemptions for professional football, enabling the NFL to absorb the rival league and obtain lucrative national television contracts. He introduced Monday Night Football and the instant replay, and presided over the creation of the Super Bowl, the most popular sporting event in the United States, and the most watched annual event in American television.

When Rozelle took command of the NFL in 1960, franchises sold for $1 million each. When he stepped down nearly 30 years later, the league had grown from 12 to 28 teams, most valued at well over $100 million, values that have continued to escalate dizzyingly in the years since. Rozelle overcame contentious team owners, rival leagues, massive court battles, and bitter players’ strikes to create the game of professional football as we know it today.

Can you describe that day in 1960 when you were chosen as Commissioner of the NFL? You weren’t the obvious candidate.

Pete Rozelle: That’s right, I wasn’t. I was with Dan Reeves, who was the majority owner of the Rams, and all of the big boys in the room during the meeting.

They had a long, intense discussion, and long voting procedures, trying to elect a new commissioner because Bert Bell had passed away. And we were there for ten days. And the group that the Rams were a part of were supporting — a lot — the San Francisco 49er club attorney, Marshall Leahy, who was the attorney in San Francisco, a nice man. And they kept voting for him. And then there was a bloc of three or four other clubs who would vote for anyone but Leahy. And that went on for ten days and 24 ballots. And finally, we broke for lunch, and at the end of the lunch period, Dan Reeves and — I think — Wellington Mara of the Giants, and Paul Brown of the then-Cleveland Browns, came to me and said, “We’re going to put you up, you know, nominate you for the job, and be voting.” And I said, “I’d prefer not to.” It had been so messy for ten days, and I said that was so far off. And they said, “Why don’t you just sit and be quiet, and they’ll ask you to leave the room.” So we went back in session, and I was totally shocked, because they had considered political figures, and big names and so forth and they couldn’t get agreement, partially because of the bloc wanting Marshall Leahy. So they decided to get off Leahy and go get on someone else. And so they nominated me and asked me to leave the room. And suggested I might want to go into the men’s room or something, because the newspaper men — there weren’t many in those days, now there’d be hundreds — but there were about 20 maybe, and they were all around the lobby. So when I went out, I went into the men’s room, and just stayed. Told them where I’d be. When someone came in, I would be just washing my hands, and I’d keep doing that until they left, and then I’d stop washing my hands, and dry them, and sit and wait. That went on for — I forget how long, maybe 45 minutes or an hour. Then they came in, took me back, and told me I was Commissioner of the National Football League. So I can honestly say I took the job with clean hands.

Why did they choose you?

Pete Rozelle: You’d have to honestly say it was partially from desperation. They would be made to look somewhat foolish with this long meeting to find a replacement for Bert Bell. Miami hotel prices in those days had to have an impact on them, because the whole economy was different for football. They had been there ten days, and so I think that was a major factor — timing.

There’s been some speculation that the team owners thought they could push around a 33-year-old, and that they thought you would be no threat to them.

Pete Rozelle: I don’t know what went through their minds, but I was sure happy. It was an amazing coincidence, being there at the right time.

So you didn’t have a vision of this when you were a kid? “I want to be the Commissioner of the NFL!”

Pete Rozelle: No, I wanted to be sports editor of the Los Angeles Times. That was my goal.

If they did assume from your inexperience that you would be a pushover, when did they learn otherwise?

Pete Rozelle: Oh, there were several incidents.

You’re in a strange position, because you work for these people, and yet, it’s up to you to enforce the constitution and by-laws that they set up. So there’s discipline involved, and you have to take issue with them on some things they might want to do, and say, “Well, you can’t do that.” But they were pretty good. Most of them understood. I know that George Halas was, of course, almost the founder of the National Football League, a great Chicago Bear coach and owner. And I remember, I had to call him in, and he flew in from Chicago. Called me from the airport, and asked if we could meet out there. I said, “No, I want to see you in my office.” And he came in and we talked over whatever the problem was at the time. But he didn’t get mad. He was very supportive of me. He had respect for authority and knew they had to have a strong commissioner. Not someone who would do just what was, at the time, the thing to do, but one that would stick to their guns and do what they felt was right.

Wasn’t there some bad blood in those years, between the teams from the large markets and the teams from the smaller markets?

Pete Rozelle: We had a problem, because in 1960, when I became commissioner, clubs made their own television contracts, and the small market clubs did not do very well. Had a real strange set-up; you had CBS carrying the games of — I think — about eight clubs, and they paid $175,000 a year for the Giants, down to maybe $75,000 in those days for the Packers. And then you had one of the teams on the Fox sports network — Sports Network, not Fox in those days — that was a Cleveland team, and they got 175. And then Baltimore and Pittsburgh had just moved over to NBC. So it was all fractionated. The clubs were competing with themselves, and there was no chance of increasing the income. So we did press for an antitrust exemption in Congress, and strangely enough, football is subject to the antitrust laws. Baseball got an exemption way, way back, and we tried to get one ourselves. We couldn’t at that time. But we did get exemption from the standpoint of selling our television rights as a package, all the teams at one time, rather than individually. They said it would not be against the antitrust laws, so we got that through and were able then to negotiate a contract with CBS. I guess at that time we were maybe getting two-and-a-half million, all 12 clubs, in those days. Now let’s see, 30 years later they average 32,500,000 a year in the latest contract they got. So that was a big thing. The big-city market clubs — like New York, Chicago Bears, the L.A. Rams — agreed to share the television money equally with the smaller markets, like the Green Bay Packers, 75,000 in the community. And Pittsburgh was not a big city in those days. That really was a thing that was most important to the league, because it made all of them compete for players, and compete with strong organizations equally.

It also had a tremendous impact on the way the public viewed football. It equalized it.

Pete Rozelle: Also, we packaged them all on the same network. Later we used several networks, but all in a package. It increased the promotion for the league. That was a big factor too.

It had an impact in equalizing the teams, too, didn’t it?

Pete Rozelle: The whole thing was equalizing the competition on the field. The sharing of income gave everyone the tools, the money, to compete equally. Now some didn’t, but management and coaching and so forth being the big difference, and players, they had the opportunity, at least, to compete equally. That was a very important thing, rather than one small market being down forever.

At the time that this all was taking place, there was no such thing as the Super Bowl. Football was not nearly the obsession with the general public that it is today.

Pete Rozelle: We were fortunate to take advantage of it, because in the early ’60s, we were the first sport to set up our own merchandising promotion company, NFL Properties, and our own film company, NFL Films. They had their own offices in New Jersey, and they filmed every game, and used those for shows, and sent them overseas for showings overseas, and did a great deal to popularize the National Football League.

Television itself was fairly young back in 1960.

Pete Rozelle: It was. As a matter of fact, I can remember in the late ’50s and early ’60s, the first talk of cable television. They called it “community antennae television” in those days. It was to service the mountainous areas, say, of Pennsylvania, that couldn’t get reception of regular television. So they would set up a cable system for handling that. There were no cable channels, it was just to give them a chance to watch television. Of course, that developed quite a bit over the next 30 years.

The success of football during your tenure now seems very smooth and rapid. Back then, in 1960, ’61, when you were fighting these initial battles, did you have a vision of what this was going to become?

Pete Rozelle: We really didn’t at that time.

We were in competition with the American Football League, and that lasted until 1966. Then I think the owners on both sides realized that something would have to be done, or the weaker clubs in both leagues might eventually fail. So we quietly arranged a merger, and got a bill through Congress permitting the merger as being not against the monopoly laws. That was really the turning point. Set up the Super Bowl, and so forth, where the winner of each of those two — they became conferences in the National Football League — the American Football League and the National Football League merged, and that created two different conferences, and then the winning teams met in the Super Bowl.

There is a certain irony, because the AFL was always interested in some kind of inter-league play, but you refused for a number of years. Is that because you wanted it on your own terms?

Pete Rozelle: Well, there was a great rivalry, as an example, for football players. For seniors coming out of college. That was our first big escalation of salaries. The owners were getting a little more from television and the players started being paid a great deal more. There was intense competition, and the National League owners didn’t want to help the American Football League achieve an inch in that way. They wanted to downplay them. So that’s why it wasn’t done until after the merger.

That sounds very polite, but you took a lot of heat for it at the time.

Pete Rozelle: I think the press took both sides of the argument. They weren’t friendly to the National Football League, while they fully understood and were friendly to the American Football League. They sniped at the NFL.

Over the years, in that very high profile position, you were discussed in the press on a daily basis. How did you handle the criticism that was directed at you?

Pete Rozelle: Our teams were traveling at the time of President Kennedy’s assassination. I remember trying to get Pierre Salinger, who was President Kennedy’s press secretary. He was traveling down with some cabinet members to Tokyo. I tried to reach him, and he finally called me back from Hawaii on the way back. And I asked him what could we do on this. We didn’t know when services were going to be, we don’t know the day of mourning, and so forth. This was on a Friday afternoon. So he told me that he thought I should go ahead and follow the team’s schedule, play the games. It was my decision. I did check with Pierre, and off the top of his head, he thought maybe we should play the games. I think it was a mistake, because it was such a horrendous thing, with follow-up on Lee Harvey Oswald, and so forth. It absorbed the nation and put them in a deep state of mourning. We had teams that had gone to different cities, ready for a game on Sunday. So we did play the games that Sunday. I think it was a serious public relations mistake. I think it would have been much better if we hadn’t, of course. I was criticized intensely for that.

Wasn’t there an element of wanting to show that life goes on?

Pete Rozelle: Some felt that way. In retrospect, I certainly think it would have been much better from a public relations viewpoint not to have played the games, because I did respect President Kennedy a great deal. I had met him through Pierre. I was close to the family even afterwards. I played in Ethel’s celebrity tennis tournament each year for about eight or ten years, and that was a lot of fun.

Almost immediately after you became commissioner, you started expanding the NFL. What was the importance of that?

Pete Rozelle: We were starting to develop strong interest, the NFL was. We had to get into some top markets to really develop this interest in the way of television and so forth, big. There were some cities I felt were very well set up to handle a team. So we did expand to Dallas and Minneapolis. They called it the Minnesota Vikings. We did that in 1960, at that meeting when I was elected commissioner. So we added two then, making 14. Then we expanded later on, we merged, presently up to 28.

Did you have a vision, when you took the job, that there would be many more teams?

Pete Rozelle: Yes, very much so.

That was a pretty daring move. It cost a lot of money to support these teams.

Pete Rozelle: Well, it was just starting to turn the corner, I felt, where it could be done without diluting the count or the money from television, and so forth.

The 1962 betting scandal was another very important crisis in your early years as commissioner. You took a very hard line. How did you make those difficult decisions back then?

Pete Rozelle: There were reports that some players had been betting on games. It was never established they ever bet against their own team. But in the final analysis, I developed enough information through investigation that — the big one was Paul Hornung, who was a great star with the Green Bay Packers, and Vince Lombardi was his coach. I remember when I called Vinnie and asked him to come in to see me. So he flew into New York. He was a remarkable man. Paul was the star of his championship team, and I laid out the information that we had about Paul, what Paul had been doing. And again, never betting against the Packers, but betting on football. Vince looked at it, he said, “Well, you have no choice, do you?” I said, “I don’t think so, Vinnie. Let’s go get a drink.” He really handled it like a man. Because coaches have an inordinate interest in their football players, and he wanted that talent on the field, and they will argue almost on any case, saying, “Well, you should let him play.” But Vince was outstanding in that way. He, the man in authority — from respect for his authority with the players, with everyone in the Green Bay organization — but he also gave authority to the commissioner.

Weren’t there a lot of people who thought you were too hard on those players?

Pete Rozelle: Yes. It’s like anything else. Some felt it was proper, some improper, so you have to take the praise with the criticism.

It seems that you have a very strong sense of integrity, and that you’re very protective of the sport, and this was a very early example.

Pete Rozelle: That’s why I did feel strongly about it. Because it’s the league that counts, and it’s the public perception of the league, and reputation and character. The character of the league had to remain strong for the reputation to be good.

Huge sums of money have become a regular part of professional football. Does that make it even more important to retain that sense of integrity?

Pete Rozelle: The commissioner’s role is really to protect the sport from inside, on behalf of the owners, players and coaches — and future owners, players and coaches. And the general public. Fortunately, the NFL has been strong. As an example, in 1960, we sold those two expansion franchises, Dallas and Minneapolis, for $600,000 a piece. That’s how much they paid to get in the NFL and be stocked with players from the other teams. Now, in the most recent sale I know of, my friend Bob Tisch, he bought 50 percent of the New York Giants for 75 million dollars — for half interest in the club. So I think the league is healthy, and the perception of the league is healthy, which is the main thing.

Back to the evolution of the Super Bowl. Did you have any idea what the Super Bowl would become when you first anticipated the conferences getting together?

Pete Rozelle: No. Particularly after the first game, because we didn’t sell out.

We expected so much, with all the publicity that had been generated during the two leagues’ rivalries. But after merging, and we set up the Super Bowl championship game, with the participants being from the AFL and the NFL, we played in Los Angeles and the stadium was only two-thirds filled. I think the top price was $12, or something. And I was shocked. But that was the last game we had without a sell-out. The only game without a sell-out.

Now I guess more people watch the Super Bowl than go to church on a given Super Bowl Sunday.

Pete Rozelle: It’s awfully heavy. There are a lot of funny stories about it, with ministers having television sets in their study, and bringing their favorite parishioners in after services to watch the Super Bowl game and having a lot of fun.

How soon did it became a real phenomenon?

Pete Rozelle: Oh, I think the next year we sold out, and I think the key one was the third game. It was the first one that the AFL won. That was the New York Jets. They butchered the NFL team. Everyone knew it was going to be very competitive, and either league could win. It was up all the way after that.

What are your recollections of that exciting game?

Pete Rozelle: Well, (Joe) Namath was a very glamorous figure. He was very mild by today’s standards, of say, Madonna, but he was an entertainer. He had great confidence in himself, as he had a right to. Before the game, I know, he went to some sports function in Miami, a couple of days before the game. He was drinking a scotch and water, and he says, “I assure you, we will beat the Baltimore Colts,” and everyone took it as bravado. You know, he’s a boastful guy. And he delivered. That was the difference. He was a very popular figure in New York and throughout the country. He delivered with that first AFL win over an NFL team.

That must have been a particularly exciting day for you. Was it?

Pete Rozelle: It was.