It was a life-changing experience...we hadn’t met many people that had been tortured or lost loved ones. And suddenly, there they were, talking to us. It’s very hard then to walk away. I was shocked people could go through some of the experiences and have their horrors denied, buried, and forgotten.

Peter Gabriel was born in Woking, Surrey, and raised on his family’s 150-acre dairy farm. His father, Ralph Gabriel, was an electrical engineer and inventor who commuted to London while employees tended the farm. Peter’s mother, Irene, played the piano and came from a highly musical family. Peter was given piano lessons at an early age, but by age nine, he had rebelled against formal musical training. He rediscovered music as a boy of 11 when he became fascinated by the drummer in a small combo playing at a resort in Spain where the family had gone on holiday. He began writing songs and finding his own path in music, teaching himself drums, piano, and the flute.

At age 13, he was sent to Charterhouse, one of England’s historic private boarding schools. Although shy, he sought out friends to play music with, and after drumming for a few bands in school, he moved from behind the drums to the front of the stage as the singer. Gabriel and his friends were inspired by American soul music, and he fondly remembers going to see the soul singer Otis Redding at a club in London. In his last year at Charterhouse, Gabriel formed a relatively stable group with schoolmates Tony Banks, Anthony Phillips, and Mike Rutherford, and they began writing original songs together. Gabriel’s band, called Garden Wall, played school dances and private parties in the neighborhood. At one school dance, Gabriel met Jill Moore, a student at a local girls’ school and the daughter of Lord Moore of Wolvercote. They began dating, although Gabriel’s focus on music now dominated his life.

A Charterhouse graduate named Jonathan King had scored a hit single with “Everyone’s Gone to the Moon” in 1965. When King returned to the school for a visit, Gabriel’s friends gave him a tape the boys had made over their vacation. King was impressed with the songs, and the singer, and secured them a one-year contract with Decca Records. He also selected the group’s new name, Genesis. He produced their first single, “Silent Sun,” released in February 1968, but the record made little impact at the time. Later that year, King produced their first album, From Genesis to Revelation. The band’s music had evolved away from the soul-inspired numbers they had originally played to more elaborate and ambitious compositions, reflecting Gabriel’s interest in folklore and mythology. A pastoral fantasy scored with acoustic 12-string guitars, vocal harmonies, and a string section, their first album failed to make an impression on the rock-buying public. Jonathan King lost interest in the group and Decca did not renew their contract.

After graduating from Charterhouse, Gabriel and his mates began looking for a new record label and new management. With contributions from their families, they acquired professional equipment and began playing bars and youth clubs up and down England. Most audiences failed to respond to the dreamy acoustic music of their first record, and they began to develop a more aggressive, rock-oriented sound. Music business entrepreneur Tony Stratton-Smith signed the group to his new label, Charisma Records, for the lordly sum of £15 a week. In 1970, Genesis recorded Trespass, their first album for Charisma, featuring a mixture of acoustic and electric material. Not long after recording the album, original guitarist Anthony Phillips left the band. Guitarist Steve Hackett joined the group, and the group’s drummer was replaced by 19-year-old Phil Collins.

In 1971, Peter Gabriel and Jill Moore married, with the blessings of their families. Although the sales of Genesis records were disappointing, the group’s live performances attracted better reviews, and they prepared to record a third album, Nursery Cryme. Although this album, too, did not sell well in Britain, it was a surprise hit in continental Europe. As the front man, Gabriel took the responsibility of entertaining the audience with improvised stories and tall tales during the band’s frequent tuning breaks and equipment failures. He later augmented these tales by appearing in a series of fanciful costumes, and the audience for the band’s live shows attracted increased attention from the music press.

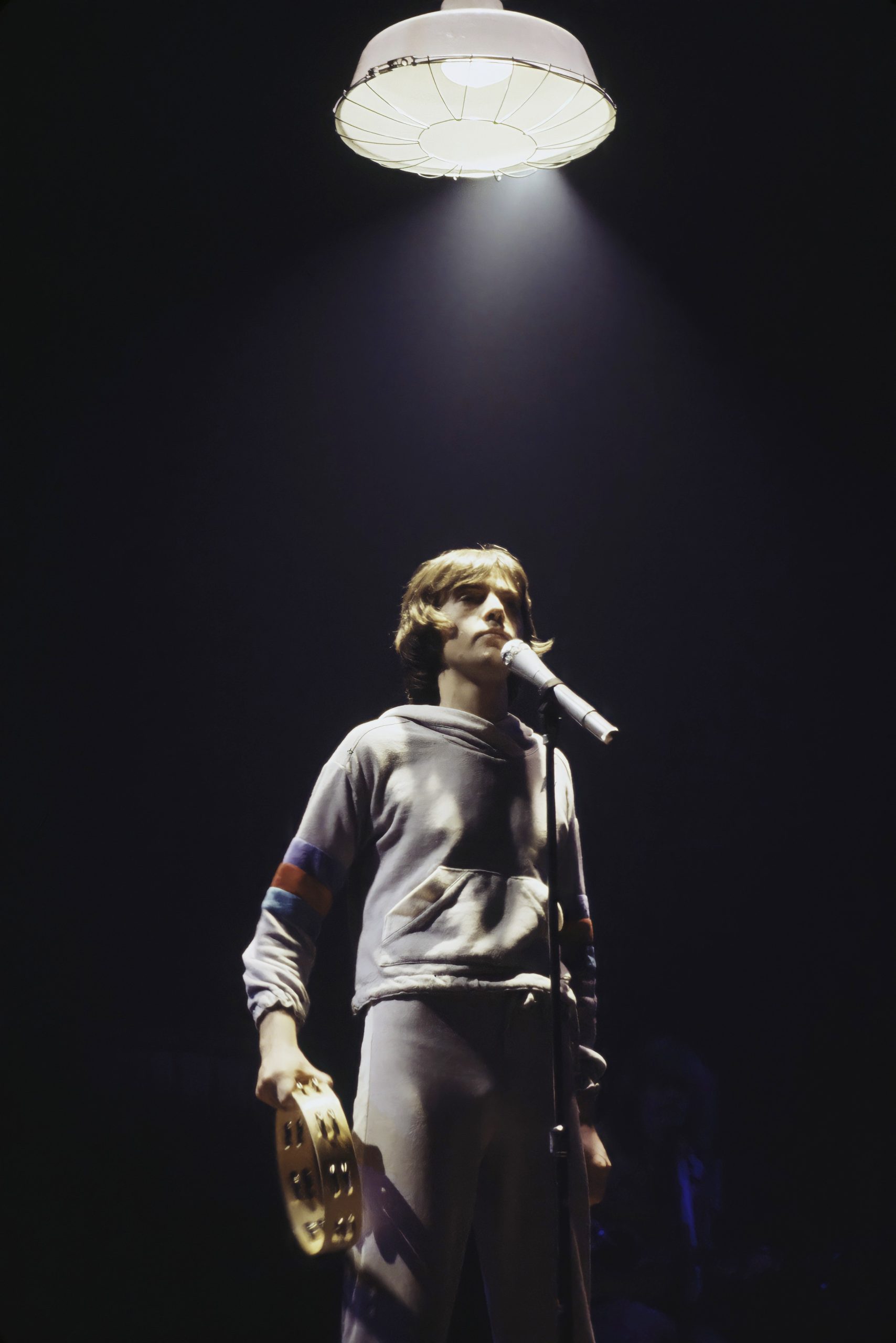

The next Genesis record, Foxtrot, added a supernatural element to the group’s fairy-tale themes. It was the group’s first album to sell well in Britain, and the band booked their first American shows, including a well-received performance at New York’s Avery Fisher Hall. Besides his singing and storytelling, Gabriel made other contributions to the band’s sound, playing flute solos, shaking the tambourine, and kicking a bass drum alongside his microphone. Gabriel’s costumes became more extravagant, with face paint, masks, capes, elaborate headgear, and glittering jumpsuits. Genesis had now become one of the most popular live attractions in Britain.

In 1973, Genesis recorded their most successful album to date, Selling England by the Pound, which included their first hit single, “I Know What I Like (In Your Wardrobe).” Gabriel’s leadership of Genesis peaked with the creation of an ambitious concept album, The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway, in 1974. The record was released with a booklet containing an original story by Gabriel, which provided a dreamlike narrative informing the songs. To support the album, the group undertook a highly profitable North American tour, which featured one of Gabriel’s most outrageous costumes to date, the notorious Slipperman outfit.

Gabriel’s wife, Jill, had a difficult first pregnancy, and their newborn daughter, Anna, required intensive medical care. In these circumstances, Gabriel was unwilling to leave his family’s side for rehearsals and recording sessions, exacerbating the existing friction between him and the other band members. In 1975, with the band enjoying its greatest success to date, Gabriel left Genesis.

At age 25, he faced the prospect of carrying on his career without the only collaborators he had ever known. He spent some months in relative seclusion with his wife and child at their home in Bath. After a year of preparation — and the birth of his second daughter, Melanie — he was ready to return to the music scene as a solo artist. His first solo album, titled simply Peter Gabriel, appeared in 1977. It featured a lush instrumental sound and produced the hit single Solsbury Hill.

Gabriel declined to provide titles for his first four solo albums, which are generally referred to as Peter Gabriel I, II, III, and IV, or by nicknames derived from their cover graphics — Car, Scratch, Melt, and Security. Gabriel toured extensively in the United States and Europe to support these albums. Shorn of the long locks he had worn in the early ‘70s, he adopted a more austere look, and by and large eschewed the flamboyant theatricality of his performances with Genesis.

His second album was produced by King Crimson guitarist Robert Fripp, whom Gabriel had long admired, and featured a darker, leaner sound but produced no hits. His third solo album, which featured Genesis drummer Phil Collins and an innovative “gated drum” sound, produced the hits “Games Without Frontiers” and “Biko.” The album, released in 1980, was a much-admired artistic and commercial success, selling half a million copies in both the United States and in Britain, where it reached number one on the album charts.

The song “Biko,” a tribute to the murdered South African human rights activist Stephen Biko, marked a turning point in Gabriel’s career. For the first time, he directly addressed political and social issues — in this instance, the struggle against the apartheid system of racial segregation in South Africa. Gabriel had long admired the work of African and Middle Eastern musicians, and his own music increasingly reflected their influence. In 1980, he founded the WOMAD (World of Music, Arts, and Dance) festival to foster appreciation of the world’s diverse musical cultures.

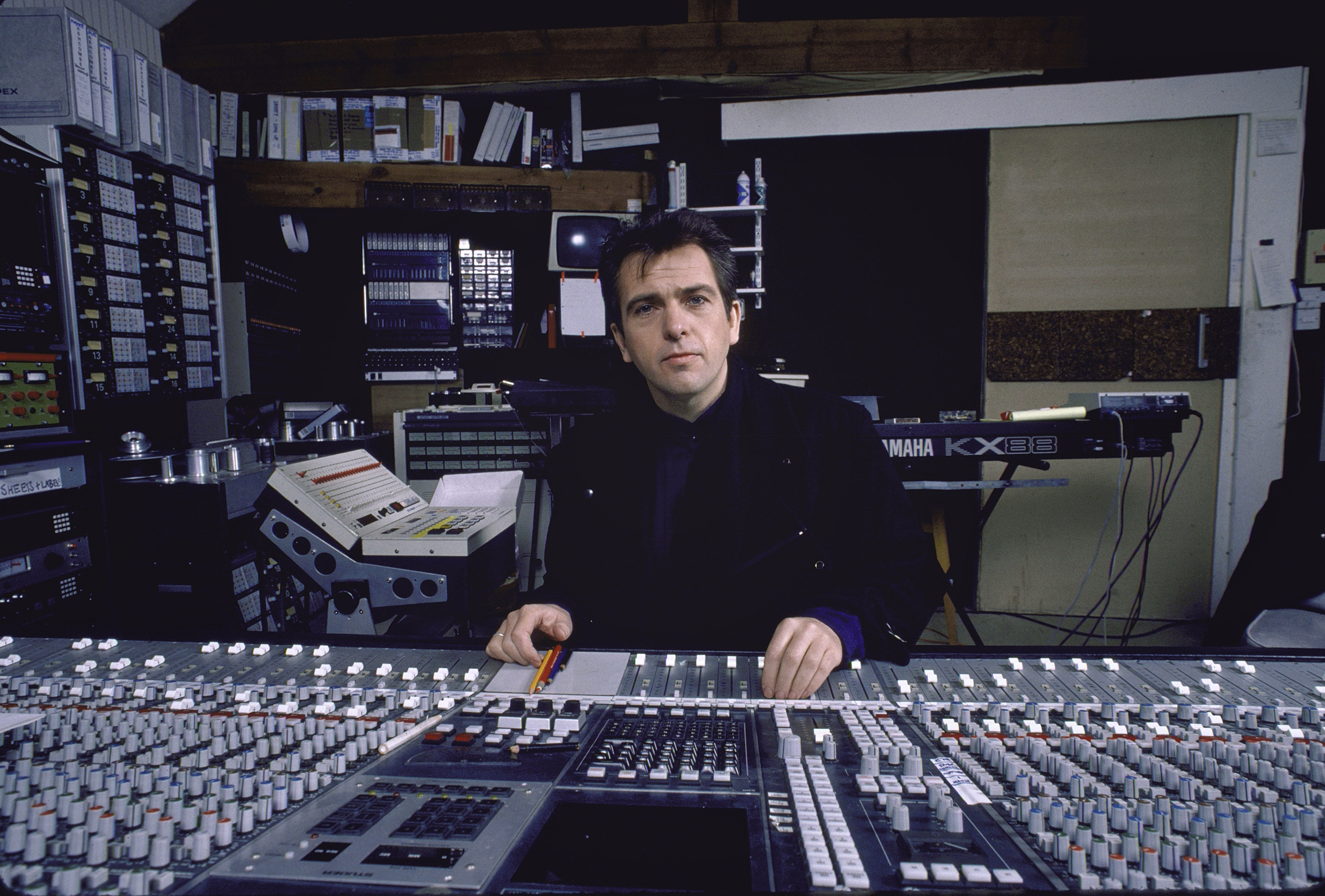

Peter Gabriel’s fourth solo album, his first for Geffen Records, was titled Security for its U.S. release in 1982. Like its predecessor, it sold more than half a million copies in both Britain and the U.S. It featured the hits “I Have the Touch” and “Shock the Monkey,” and was notable for its creative use of digitally sampled sounds, reproduced with the Fairlight CMI sampling computer. The technique had previously been the province of experimental musicians, but Gabriel’s use was the first to reach a mass audience. Digital sampling has played a prominent role in popular recorded music ever since. The singer’s theatrical flair was once again on display in the video for “Shock the Monkey.” It became a favorite on the music video channel MTV, and the song became Gabriel’s first Top 40 hit in the U.S.

Four years elapsed between the success of Security and Peter Gabriel’s next solo album, but when it came, it would be the greatest success of his career. His 1986 album So featured the songs “Sledgehammer,” “In Your Eyes,” “Big Time,” and “Don’t Give Up the Fight,” a duet with singer Kate Bush. The album reached number one on the UK album chart, while the song “Sledgehammer” was the top-selling single in the United States. Gabriel received four Grammy nominations for his work on the record, which sold more than eight million copies worldwide, including two million in the UK and five million in the U.S. It has been estimated that the video of the album’s single, “Sledgehammer,” is the most played selection in the history of MTV.

Over the years, Peter Gabriel’s song “Biko” had spread around the world and become an informal anthem for human rights activists. Gabriel was invited to perform in the “Conspiracy of Hope” tour, a series of benefit concerts for the international rights organization Amnesty International. He would play an even larger role in organizing subsequent concert tours to benefit Amnesty. A year of commercial success and escalating humanitarian commitments, 1986 also saw the end of Gabriel’s marriage to Jill Moore.

Fulfilling a longtime interest in cinema, Peter Gabriel began composing film scores in the 1980s, starting with the film Birdy in 1985. His score for Martin Scorsese’s 1988 film The Last Temptation of Christ was released as the album Passion, which brought Gabriel a Grammy Award, his first, for Best New Age Performance.

Two years after his first Amnesty concerts, Gabriel led the 20-concert “Human Rights Now!” world tour. In 1990, he traveled to Chile for the “Embrace of Hope” tour, celebrating the country’s emergence from years of military dictatorship. Gabriel’s touring and activism had largely kept him out of the studio until 1992, when he released the album Us, in which he reflected on the failure of his marriage and his strained relationship with his children.

Gabriel undertook a world tour to support the Us album and shot a series of innovative videos, winning Grammy Awards for the videos of “Digging in the Dirt” and “Steam” and for his concert film Secret World Live. The same year, he founded the nonprofit organization Witness, which equips activists with film and video technology to document human rights abuses. Like his inventor father, Peter Gabriel has a longstanding interest in new technology. In 1999, he co-founded OD2, one of the first online services for downloading music.

Ten years elapsed between Gabriel’s fifth and sixth studio albums. He returned to the studio in 2002 to complete Up, a self-produced collection of longer songs. The album produced no hit singles but sold well worldwide, due to Gabriel’s international popularity, bolstered by years of touring. That year, Gabriel married Irish costume designer Meabh Flynn; they now have two sons, Isaac Ralph and Luc. His daughters by his previous marriage, Anne-Marie and Melanie, have worked with him often over the years, Anne-Marie as a filmmaker documenting his performances, Melanie as a vocalist in his live shows.

In 2006, Peter Gabriel sang John Lennon’s “Imagine” for the opening ceremonies of the Winter Olympics. Also that year, the World Summit of Nobel Laureates selected Gabriel for its Man of Peace Award, presented by Mikhail Gorbachev and the Mayor of Rome, Walter Veltroni. The following year, Gabriel and his friend, Virgin Records founder Richard Branson, recruited distinguished international statesmen, including former U.S. President Jimmy Carter, former Irish President Mary Robinson, and former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, along with Archbishop Desmond Tutu and South African President Nelson Mandela, to form an organization they called The Elders, leveraging the moral authority of their long experience to resolve civil and international conflicts.

Gabriel received another Grammy for the song “Down to Earth,” from the 2008 animated film WALL-E. Genesis was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2010. The same year, Gabriel released Scratch My Back, an album of songs by other writers. The following year, he produced New Blood, a collection of his old songs performed with full orchestra. Peter Gabriel was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame as a solo artist in 2014. Today, he makes his home in Wiltshire, England, where he maintains a commercial recording studio and a record label, Real World Records. In April 2019, Real World Records released Rated PG, a compilation of songs Gabriel has composed or sung for motion picture soundtracks.

Peter Gabriel first rose to fame as the flamboyantly costumed lead singer of the innovative progressive rock band Genesis. After leaving Genesis in 1975, Gabriel launched a successful solo career with the hit single “Solsbury Hill.” His 1986 album, So, sold over 6.8 million copies worldwide. His video “Sledgehammer” remains the most played music video in the history of MTV.

Since 1980, when he released the anti-apartheid single “Biko,” Gabriel has championed a series of humanitarian projects. He has participated in numerous benefit concerts for different causes, including Amnesty International’s “Human Rights Now!” tour, which traveled the world in 1988.

In 1980 he founded WOMAD (World of Music, Arts and Dance — to present the world to the world ) which has organized 170 festivals in over 30 countries. He conceived of the human rights organization Witness.org in 1992 to introduce citizen video and technology into human rights campaigning. He also founded The Elders.org with Nelson Mandela and Richard Branson in 2001 to bring together a respected group of world leaders, whose influence could stem not from political, economic or military power, but from experience, integrity and wisdom. His other work interests have been in innovative technology, especially in digital media, audio, music, visual language and more recently health care.

To date, Gabriel has won six Grammy Awards and 13 MTV Video Music Awards. He has been inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame twice, once as a member of Genesis, and again as a solo artist. In recognition of his many years of human rights activism, he received the Man of Peace award from the Nobel Peace Prize laureates, and TIME magazine named him one of the 100 most influential people in the world.

How did your parents feel about your starting Genesis when you were still in school?

Peter Gabriel: There was a lot of discussion about whether we should continue with music. At that time, you know — the school now would be very proud of Genesis and our history — they weren’t really supportive. They sort of tolerated a rock group. I remember, Mike Rutherford was told not to carry on playing and mixing with disreputable types. So this was something that for us was really important because it was not quite Tom Browne’s School Days, but it was a formal English public school with discipline, not a lot of compassion. And you felt — there was a film Lindsay Anderson did called If, which sort of captured, I think, the emotion of the experience.

But the tighter the discipline, the more human nature wants to rebel against it. So music was our way, and we would go down — there was a room where you could play billiards downstairs, but it was a small Dansette record player. And so the very few visits we were allowed to make to the town, I would go down to Godalming and buy Otis Redding or Nina Simone or whatever it was that was firing me up and turn it up full volume in this little room. And then we’d go upstairs to the dining room where the only piano was. And there’d be a big competition. Sometimes you’d have to run into the kitchen and climb through the hatch in order to sit down because it was first-come, first-served at the piano after the lessons finished. So there was a lot of competition.

But both Tony Banks and I were part of that sort of songwriting team. And then we had an invitation to join a couple of others in the school to make demos that were sent to various places, including to Jonathan King, who gave us our first recording contract and got us into a studio.

Did you see yourself as a songwriter or a singer in those days?

Peter Gabriel: I saw myself as a drummer first and songwriter. Yeah, we were planning to be songwriters. We didn’t really want to be a group. The harsh reality of dreams of writing hits is that no one is interested in recording them. So we had to start playing them ourselves. And then that evolved and we wanted to explore different types of music. It was the beginning of the ‘60s and merging different styles seemed to us to be exciting and revolutionary. So that’s what we were trying to do.

In your days with Genesis, you were pretty well known for your spectacular costumes. What was the idea behind that?

Peter Gabriel: The idea was to get rich and famous. We were in a group that was sort of disappearing into the oblivion. I mean that was one side of it. But there was another side, which was an evolution, but we loved the sound of 12-string guitars. This was old days, so it meant there weren’t electronic tuners. Three guys with 36 strings at their command would sit there twiddling knobs until they got their guitars in tune. So there were long pauses between each song. And if you’re in a small club and there’s an audience and a bunch of musicians, you just got something going, and then they’re sitting there and all the energy is being dissipated. They look to the mug behind the microphone to do something. So I started telling stories.

So partly, there were characters coming out in these stories and emerging. We had on one album a character which Paul Whitehead had created with a fox head and a red dress. And I sat around with Paul Conroy, who was working at our record company at the time. And he was saying, “Well, why don’t we get someone to walk around the gig in a fox head and a red dress?” And I thought, “Oh, I might as well give that a go.” So I went into my wife’s wardrobe and pulled out a red dress, which was, in fact, an Ossie Clark dress. But at that point, I was thin enough to get into it. And we got this fox head made up.

I remember the first gig I wore it was in this former bullring in Dublin, which was not exactly the most enlightened, transgender environment. And there was a shock. Literally, you could hear a pin drop when I walked out in this costume. And I thought, “Oh, that’s interesting.” And the band, of course, didn’t really know that I was going to do this. I had mentioned something with the fox head, but I didn’t discuss it because I knew there would not be a majority vote going my way. And the same when I came up with a whole lot more costumes of the rainbow.

And the following day, we got on the front page of Melody Maker, and suddenly, from £50 a week per head, we were on 150. Life was looking up. So there were practical advantages to the costumes. But it was actually a lot of fun, and sometimes, when you’d come out — and this weird keyboard sound, and this dry ice, and I’m wearing this sort of UV make-up and bat wings — it was like a sci-fi moment, and you took people to some other place. So we divided a lot of people. We weren’t popular in this country. But we did well in other countries, and we started building a reputation for the band. So I think the musicians in the band were both appalled and delighted.

What’s it like to be a rock star? You look out and there are thousands of people, and they know every lyric, and they’re moving to your music. What does that feel like?

Peter Gabriel: Well, it’s a bit like the seven-year-old jumping on the table in the family get-together and showing off, but it’s on a bigger scale. But actually, when you feel the emotion of — because I’m a real mixture between this sort of show-off extrovert and a very shy person. But when you feel the engagement and you feel the warmth of the people, it’s like nothing else. So it’s a wonderful feeling. And particularly, it’s the interaction with other musicians because it’s a free-flowing emotional language. I mean some nights it feels like you’re just doing the same thing and you’re thinking about did you get your socks in the laundry. But other times, you’re very present. And it’s an amazing experience, a great privilege.

Listening to what motivated you as a young man, it doesn’t seem like fame was really your motivation, but you certainly had your share. What are the ups and downs of that?

Peter Gabriel: Well, I think, in truth, we’re a mixture of our higher and lower natures. So there’s definitely part of me that wanted attention and girls, and the other part of me just loved music and wanted to follow my heart. I think the truth is always somewhere in-between, is composite. I always thought of myself as a weekend rock star. You know, it was a fun place to get your ego stroked but toxic if it’s your permanent abode.

Genesis was successful when you were all so young, and you were only 25 when you walked away. Why did you do it? Why start over again on your own?

Peter Gabriel: There were a number of things. I think things — you know, I’m quite fond of them all to this day. But you know, band politics is just classic. So it got to the point where to get something done, you’d have to persuade — Tony Banks and I, we were often best friends/worst enemies. I would sometimes try to persuade him that what I wanted was his idea. And he was always very protective of the keyboard. He didn’t want anyone else getting near his keyboard, whereas I wanted to express myself and play with that.

But then I think it was a decisive thing when my first daughter, Anna, was born and they didn’t think she would survive. There was a whole number of things. My wife, Jill, wasn’t allowed to see her then, and she was in an incubator. It was the most traumatic experience of my life at that point. And the band were very unappreciative. Phil had a child then, but on the whole, we were trying to get The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway recorded at that time, and that was in far West Wales, and the drive was pretty hellish, getting there and back. There was no question in my mind that family comes first. So I think things got soured at that point.

And then I had an invitation from William Friedkin, who had just done The Exorcist and The French Connection at the time. I had considered a place in film school. I always loved film. He was trying to get a sort of new team of young people to come and do something different in Hollywood. He didn’t want me for the music. He wanted me for ideas.

There are so many strange images in your songs and stories. Did these come to you without drugs?

Except for the odd puff — and I did inhale — I’m a pretty drug-free environment, unlike most of my musical compatriots. I think the only one I was interested in was acid, and that was because it could take you somewhere else, and I was a bit scared of losing control. I’ve actually got some friends my age who’ve just taken acid for the first time. Very smart. So it’s still something that I think maybe one day. But I also saw a lot of destruction around the drugs.

You did some pretty creative filmmaking with your music videos — “Sledgehammer,” for instance. There’s a lot of crazy stuff in there. Did you have any idea how popular that would be?

Peter Gabriel: We knew we were doing something different. I mean I had this very gifted director, Stephen Johnson, and he brought in the Brothers Quay, and I brought in Aardman Animation. And it was for about a month — two weeks of really focused creative work. It was just this extraordinary maelstrom of ideas and people trying stuff. We did it down in Bristol. It was slow and painful, from my point of view, but we had the sense that we were doing something different, and it was a lot of fun. We’re just putting something together now which retells the story of it with Aardman. So that — I just saw it the other day, with interviews from people that I haven’t seen since that session. So that was interesting.

How long did it take to make the “Sledgehammer” video, from beginning to end?

It was, I think, probably a month from when it was first discussed, but the focused part was about two weeks. Stephen and I were generating some ideas, and then the Quay Brothers and Aardman also brought in a lot of — so it was about a week of actual filming on these little stages with different sets for the different parts of the video.

How did you come to write the song “In Your Eyes”? It’s such a different kind of love song.

Peter Gabriel: I was in love with a lot of African music around that time, and bits of it were written in Senegal. But one of the ideas that interested me in African music is that there was a capacity to sing a love song that could be a love for a woman or a love of God. And the two could be confused with no problem — that they could be about love. Whereas, in our society, spiritual was one side, sexual and romantic was another. So that fusion was what I was trying to explore lyrically and in the music. There was definitely some African influence. So it has a life to it that flows effortlessly. And then I was working with Youssou N’Dour, who does this amazing singing. There’s this sort of angelic voice at the end. So I think a combination of those things helped it to work.

What did you think when you saw John Cusack playing your song on a boombox in that movie Say Anything?

Peter Gabriel: We got asked by Cameron Crowe, and he’d done a couple of films that I enjoyed a lot. So I was very happy about it. I think Cusack is a great actor. I had no idea it was going to become this sort of iconic thing, but I’m very grateful that it was chosen, because it’s one of the most parroted scenes in Hollywood.

You’ve done so much work for human rights around the world, especially Amnesty International. The “Human Rights Now!” tour with Springsteen, Sting, Tracy Chapman. What were you trying to accomplish there?

Peter Gabriel: Well, I sort of fell into human rights, really. You know, I came from a comfortable background. And then, when I put my calling card in, I think, was when I wrote the song “Biko.” I’ve been interested in what goes on in the world. When Steve Biko was arrested, a lot of people thought that the publicity surrounding his arrest would be enough to protect him. So there was a real sense of shock when we heard that he’d died or been murdered.

I was questioning, at the time, whether this was something that I could do. You know, there was a lot of flack in this country if you come from a middle-class background or a comfortable background. It’s often from middle-class journalists who want working-class heroes. But in the backwater that is Britain, we get very hung up on all this sort of stuff. But it made me question whether I could write an overtly political song and be taken seriously. I was friendly with Tom Robinson, who had been a sort of outwardly very vocal gay activist. He had a song, “Sing If You’re Glad to Be Gay.” And I remember Tom saying to me, “Actually, if you get attention and money going in the right direction, who gives a —” you know? “Let’s just get on with it.” And that was good advice.

But as soon as that song was out, I was asked to do Amnesty things. And U2 were doing a “Conspiracy of Hope” tour in ’86 in America. So Bono wanted me to get out there. And I took over his role in ’88, trying to hustle musicians into doing this “Human Rights Now!” tour with Jackie Lee. And it was a sort of life-changing experience for many of us because, you know, human rights means something you read about, see in the Guardian newspaper. But we hadn’t really met many people around the world that had been tortured or lost loved ones. And suddenly, there they were, and they were talking to us. It’s very hard then, at that point, to walk away. I found it very compelling, and I was also shocked that people could go through some of these experiences and then have their horrors totally denied, buried, and forgotten.

It became one of the most powerful anti-apartheid, human-rights songs ever recorded. And what does that feel like, that this song became part of a movement and actually had a pretty big political impact?

Peter Gabriel: Well, I heard people would sing it in South Africa, and it was used in rallies, and so on, and in stadiums. So that was great to hear.

When we did the “Human Rights Now!” tour, in fact, it was towards the end of the apartheid government, and there were interesting discussions — whether we should go to South Africa or not — because we’d been asked by the anti-apartheid movement not to go. There was a cultural boycott. Yet Youssou N’Dour and Tracy Chapman, the black artists who were with us, they thought, “Actually, no, this is part of a process that sort of opens things up and liberalizes.” So we had those discussions, and we ended up — Bill Graham was there, and he used to have these two planes: one full of gear and the other full of musicians and crew. And occasionally, when gigs were canceled or people got scared of us, we’d be there with a map of the world. Where can we land our planes? It was quite unlike any other tour. So we went to Harare instead, where — at that time, Mugabe was a hero, and it was sort of a country full of hope, after they kicked out its colonial past, and seemed to be open and moving forward in a very positive way.

We’ve seen the video of you singing “Biko” in other countries — Argentina, Chile. It seems like the whole crowd — thousands of people — are listening to your every breath. What does that feel like?

Peter Gabriel: Well, I think, in Argentina and Chile, where people have been thrown out of airplanes that have protested — horrible, horrible things had happened — to have this big juggernaut of a tour roll into town, into the stadium, it was like a big thing for them. They party like a liberation party. So it meant a lot to the people there, and it was fantastic for us to be up on the stage and feel their celebration and their determination. In Chile, we’d been in this stadium where a lot of people had been murdered. So it was sort of — they were conducting their exorcism, and we were the catalyst.

What did the “Human Rights Now!” Tour accomplish?

Peter Gabriel: Well, I know Jack Healey and Mary Daly, who we worked with as… part of Amnesty had been to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which all these countries around the world had signed and very few put into practice. Because it covers many areas, including health, employment, housing. It’s not just what people normally think of under the human rights banner of sort of freedom of expression and the right to protest peacefully, et cetera. But I think the membership of Amnesty was doubled around the world as a result of that tour. I think it was important. And for all of us, as musicians, I think it changed the way we saw our role.