One thing that can never be sacrificed is your preparation and your work ethic.

Peyton Williams Manning was born in New Orleans, Louisiana. He is the second of three sons of quarterback Archie Manning, who enjoyed an impressive career in the National Football League, primarily as quarterback for the New Orleans Saints. Peyton Manning recalls an upbringing balanced between his father’s fame and solid family values. Archie Manning didn’t pressure his sons into competitive sports, but never hesitated to offer support when needed. Basketball, baseball and football were always part of the Manning household, and Peyton attributes his early athletic development to the shared family enjoyment of these sports. He believes his passion for football, in particular, stems from the fundamental lessons his father taught him.

The oldest Manning brother, Cooper, was another mentor to his younger brothers, and excelled in high school football as a wide receiver. By his senior year, he was All-State, catching everything thrown by sophomore quarterback Peyton. Cooper was heavily recruited by Division I-A schools, ultimately deciding on his father’s alma mater, the University of Mississippi. In 1992, Cooper Manning was diagnosed with spinal stenosis, a congenital condition of the spinal column, which abruptly ended his plan for a professional football career. He went on to recover from successful surgery, graduate from Mississippi, and develop a flourishing business and family life in New Orleans.

Peyton Manning’s impressive stats (7,207 passing yards and 92 touchdowns) at Isidore Newman School in New Orleans were enough to attract the attention of the highest-ranking Division I-A college football teams; as a starter, he held a 34-5 record. In his junior year, while visiting off-season training with his father, he jumped into the quarterback spot for New Orleans Saints receivers as they practiced running patterns. The following year, Peyton was the number one recruited quarterback in the nation. He was expected to follow his father and brother to Ole Miss, the University of Mississippi, a distinguished football school with a solid program for developing a top high school player into a top NFL draft pick. But Peyton diverged from his father’s path and chose the University of Tennessee, a leading football school that regularly plays Saturday games to crowds in excess of 100,000. Tennessee became the perfect platform for Manning to showcase his natural talents. Led by Coach Phillip Fulmer, Manning’s game matured, along with his talent for team leadership.

By his junior year, Manning had earned enough academic credits to graduate. An All-American, his impressive stats drew the attention of the NFL (11,201 passing yards, 863 complete passes and 89 touchdowns). Breaking again from expectation, he decided to stay at the University of Tennessee for his senior year and forgo the 1997 NFL draft — giving up a likely first round draft and guaranteed signing bonus. Instead, he moved off-campus to enjoy his final year, developing friendships he prizes to this day.

Manning’s senior year stats were again impressive (3,819 yards, 36 touchdowns). Before completing his college athletic career, he received the prestigious Sullivan Award, given to the nation’s premier college athletes, not only on the basis of athletic ability, but on qualities of character and leadership as well. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa with a bachelor’s degree in speech communications. In the spring of 1998, as the NFL’s number one overall draft pick, he was signed by the Indianapolis Colts.

Manning soon found his rhythm with the Colts, leading them to impressive regular season records and seven Pro Bowls. After Tony Dungy joined the Colts as head coach in 2002, the Colts were reliable winners during the regular season, but repeatedly met defeat in post-season play. For three consecutive years, the Colts lost their conference championship, shutting them out of the Super Bowl.

The Colts fell to the New England Patriots in the 2003 AFC Championship (24-14). They faced their nemesis again in the 2004 playoffs, but they never saw the end zone, and suffered a rough loss (20-3). Despite these losses, Manning won the annual Associated Press poll of 50 sports writers and broadcasters and was named Most Valuable Player in the NFL for both the 2003 and 2004 seasons. In 2005, the Colts finished their regular season (14-2) seemingly ready to erase the memories of their post season losses; but they found their home field advantage, and their shot at the Super Bowl, slipping away by the fourth quarter, as they again suffered defeat, this time at the hands of the Pittsburgh Steelers (21-18).

In 2004, Peyton’s younger brother, Eli, was drafted into the NFL from the University of Mississippi. They met on the field as professional NFL quarterbacks for the first time in the 2006 season opener. Eli Manning, quarterbacking for the New York Giants, had home field advantage, but the Colts took an early lead in the first quarter and never allowed the Giants to get ahead. In the second quarter, however, Eli completed a pass to wide receiver Plaxico Burress and scored the first of three touchdowns against the Colts’ defense. Peyton Manning later remarked that he usually wants his defense to hit the other quarterback as hard as possible, but he didn’t want to see his brother hit that hard. He felt a sense of pride in Eli, who threw two touchdown passes against Peyton’s own defense. On game day, the passionate and competitive sportsmen, although brothers foremost, each wanted to walk away victorious, but Peyton’s Colts beat Eli’s Giants, 26-21.

By 2006, Manning had seen enough of conference championship play to know his time had come. He continued to break NFL records with staggering stats. He is the only quarterback in NFL history to have thrown over 12,000 yards in his first three seasons. He achieved 100 touchdowns by his 56th career game and dominated the Colt record books, holding the top seven totals for most passing yards within a single season. Tenacity and tireless conditioning allowed him 128 consecutive game starts.

On February 4, 2007, Peyton Manning’s passion and talent for the game — combined with hard work, dedicated training and mental readiness — paid off at last, as he led the Colts to a Super Bowl victory over the Chicago Bears (29-17). Standing beside Coach Dungy, Manning was named Most Valuable Player of Super Bowl XLI. After the 2008 season, the Associated Press named him Most Valuable Player in the NFL for a third time, tying the league record of Green Bay Packers quarterback Brett Favre. Manning broke the record the following season, when he was named Most Valuable Player in the league for an unprecedented fourth time. In February 2010, he led the Colts to the Super Bowl again, only to lose to his old hometown team, the New Orleans Saints.

In the offseason, Peyton Manning fulfills the typical obligations of a professional athlete — endorsements, public appearances and television commercials — but his work ethic compels him to excel in his off-the-field activities as well. In 1999, he established the PeyBack Foundation — supporting schools and youth programs in New Orleans, Louisiana and Tennessee and regularly participates in sponsored events to ensure its success. The Foundation hosts thousands of underprivileged children at events throughout the year — such as Colts home games, Thanksgiving dinner for children in foster care, and Christmas dinner for Indianapolis’s inner-city youth. In 2000, the annual PeyBack Classic was launched, enabling five inner-city Indianapolis high school football teams to play in the city’s RCA Dome. Peyton and his father also participate in Play It Smart, an educational program funded by the National Football Foundation for high school football players from disadvantaged environments. All the Manning men participate in the Manning Passing Academy, a family-owned and managed football camp.

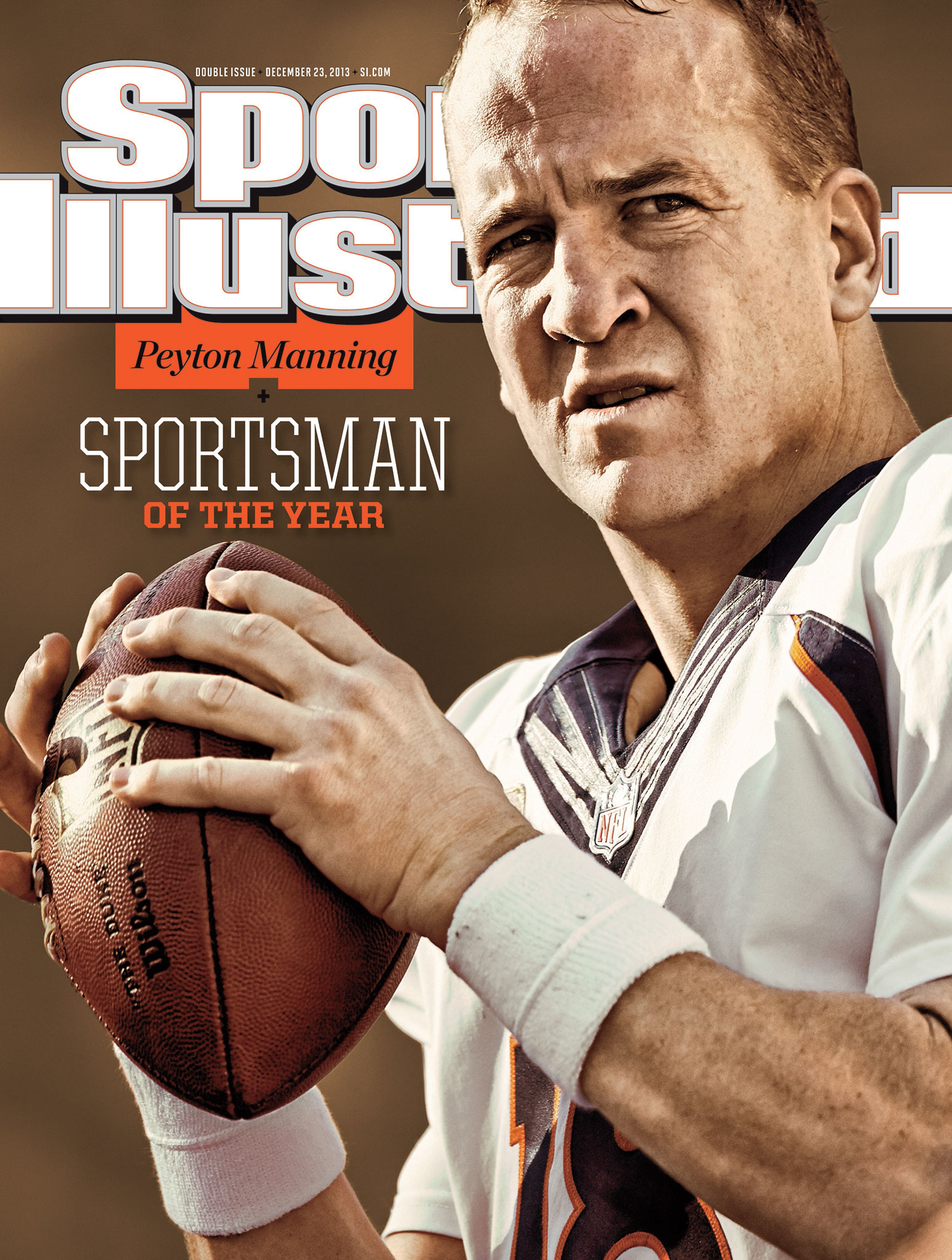

On St. Patrick’s Day in 2001, Peyton Manning married longtime girlfriend Ashley Thompson. The couple maintained close ties to family members in Louisiana, Mississippi and Tennessee, while continuing to reside in Indianapolis with their two children. A neck injury sidelined Manning for the 2011 season, although he had signed a five-year $90 million contract extension with the Colts. In March 2012, after 14 seasons in Indianapolis, Colts management released Manning from his contract. A host of NFL teams reportedly sought his services, and within weeks, Manning signed a five-year contract with the Denver Broncos for a reported $96 million. At an age when many players contemplate retirement, he was coming close to a single-season record for touchdown passes and passing yards. In his second season at Denver, he led the Broncos to an 11-3 record, throwing 47 touchdown passes. In 2013 Sports Illustrated magazine named him its “Sportsman of the Year.”

In January 2016, as sportswriters recounted the quarterback’s past injuries and predicted the imminent end of his career, Manning took the field with the Broncos against longtime rivals the New England Patriots. The 39-year-old Manning led his team to victory once again, playing his second straight game without an interception and advancing the Broncos to the 2016 Super Bowl. The game would be Manning’s second Super Bowl, and the first for Denver in 17 years.

On February 7, 2016, the Broncos faced the Carolina Panthers in Super Bowl 50. The Panthers were heavily favored to win, but Manning and the Broncos scored a memorable upset. The victory made Peyton Manning the first quarterback in the history of the game to win Super Bowls with two different teams. The game was his 200th career win, a new NFL record. The following month, he announced his retirement, ending an 18-season playing career on an incomparable high note.

At the end of his junior year at the University of Tennessee, Peyton Manning found himself in an enviable position. The star quarterback of the Tennessee Volunteers had already acquired enough credits to graduate with honors and was certain to be the first pick in the 1997 NFL draft. He stunned the football world by passing up the chance to go pro at age 21, choosing instead to remain in school another year and continue his studies. When he graduated in 1998, he received Phi Beta Kappa honors and the coveted Sullivan Award as the nation’s premier student athlete, a prize based on character and leadership as well as athletic performance.

After joining the Indianapolis Colts as the first pick in the 1998 NFL draft, he shattered the league’s records for passing and scoring. In his first nine seasons, Manning completed more passes, and threw for more yards and more touchdowns than any other player in a comparable span of time. He was named Most Valuable Player in the regular season three times, an NFL record, and made seven Pro Bowl appearances. He also recorded four perfect games, another NFL record. In 2007, he led the Colts to victory in Super Bowl XLI, winning Most Valuable Player honors in the championship contest.

In 2012, Manning moved from the Indianapolis Colts to the Denver Broncos. In his late 30s, he continued to outperform younger players, ending his 18th and final season in the NFL by leading the Broncos to a world championship in Super Bowl 50. This 2016 victory made Manning the first quarterback in NFL history to win 200 games, and the first to win the Super Bowl with two different teams.

Peyton, you’ve achieved every quarterback’s dream, leading your team, the Indianapolis Colts, to a Super Bowl victory. What prepared you to be a professional athlete, and to succeed at it?

Peyton Manning: I think experience is the best teacher in all facets, and so to play college football in a place like Tennessee, extremely high-profile program, playing on national TV every Saturday, great big crowds and demands on your time as a student athlete, I think that experience prepared me as much as it could for the professional ranks. There was a major adjustment to the physical part of the game, the speed of the game, the complexity of defenses. There is a major adjustment there. I think playing at Tennessee prepared me as much as it could, but there are still going to be those growing pains, and then the media demands are more intense, but you have a preparation.

The biggest challenge for most kids, and for me, is the adjustment of having money in your pocket. That is the biggest change. Football for me — sometimes I am kind of embarrassed to say it — it was my first job. When I was in the summers, I was playing so much baseball and working out for football. I was kind of ahead of the curve as a high school kid, as far as off-season workouts as a football player. Most kids, they play football when football season starts, but I was throwing pass patterns with my receivers in May, June, and July. I’m calling them, going, “Where are you? It’s 12 o’clock,” and this guy is going, “Well, I have a job this summer.” I’m going, “Well, that’s not going to cut it. You need to be here throwing with the quarterback.” I had my chores at my house or whatnot, but I never had an office job or never had a, you know, employee contract. When I signed my contract with the Colts, that was the first contract I’d ever signed.

I think the worst question that the media asks athletes when they sign their contracts, or when they get drafted, is “What are you going to do with your money?” That’s a bad question. There’s not a good answer that people want to hear come from that. I blame the media for asking the question. But the answer that I gave, which I think all of them should say, is “I’m going to earn it.” That’s what I said, “I’m going to earn it,” and not, “I’m going to go buy this or buy that.” I’m going to go earn it. That is how I have always felt about the money that you make as an athlete, the money that you are paid on your potential, to go earn it, to make the owner and the president happy about the investment they made in you, about working hard to be the best player that you can be.

There is more to what you do than just run out on the field and play. There is a mental aspect too, isn’t there?

Peyton Manning: No question.

Peyton Manning: The cerebral part of the game is the most challenging part of the game. You wouldn’t be in the NFL if you didn’t have the physical skills. I’ve spent tons of time, like I said, the workouts as a high school kid, lifting weights, running by yourself. You do that, but you have to do that. The cerebral part is where you can advance yourself and (what you) have to constantly stay on top of. Both of them, really. If you ever stop working out, that is when you get injured, you get behind. But you have to stay so sharp mentally. I think sometimes you can get away with the physical part with being a great athlete. I can overcome that, but the cerebral part, you can’t get behind in the mental aspect of the game. Everything happens so fast.

Before you get to the actual physical part of the game, before you get to trying to avoid the 300-pounders, or completing passes against these guys that are fast, you have noise, which is an irritant. You can’t hear. How many other people work where you just can’t hear? You have weather, 60 percent of the time. Sometimes you’re playing in a dome, it’s perfect weather, but weather’s a factor. You have time. That’s the big difference. Baseball players, there’s no time. There’s no clock. The guy can pitch whenever he wants. We have to operate under a clock, and then you have ten other guys that you’re trying to coordinate out there. So if you are not strong mentally, and sharp mentally, and rested, you will get behind in that aspect of the game.

Sports writers and sportscasters talk about character. How do you define character in an athlete?

Peyton Manning: I think character is what you’re doing when nobody else is around. To me, that’s the best way that I know to describe it. Are you the right kind of guy? Do you have the right things inside of you? Do you love the game? Like I said, would you play for free in the NFL? Obviously, I wouldn’t tell my owner that, but I would. I think you want to be around those kind of guys, guys that love it, guys that are thinking about it. They always say, “Don’t take your job home.” When you go home, don’t take it. I don’t agree with that. I think if you love what you do, there is nothing wrong with being home with your family and thinking about the game that Sunday, or thinking about, “I might need to do this.” That means you love it. That doesn’t mean you’re obsessed with it. That doesn’t mean that your priorities are out of whack. That means you love what you do. I think it has a lot to do with the character of the guys that you have on your team.

Another thing sportswriters talk about is “intangibles.” What are intangibles?

That’s one of those buzz words that’s just kind of been created. That’s the big thing, when guys are coming out of the draft and the analysts are breaking him down, they say, “Well, he’s got the physical part. I’m not sure if he has the intangibles.” Well, give us a list of something. Tell me you need something. You hear the term “the sixth sense” and “in the pocket,” or “He can run, but you have to feel these guys rushing you,” and there’s something to that. I guess that would be an example of an intangible. Do you just feel something? Do you feel somebody about to hit you? Do you slide up or do you slide the other way?

I think what they’re talking about is that ability to elevate the rest of the guys around you. Your presence probably has a lot to do with it. That might be considered an intangible, something that you can’t touch or whatever, but just when you walk into that huddle, when you walk into that practice field, letting everybody else know it’s time to get down to business and, “Hey, we got a chance with this guy in the huddle.” I think quarterbacking especially, you need to have a presence about you and the way that you walk and you carry yourself and the way that you speak.