It’s like a melody. You can study orchestration, you can study harmony and theory and everything else, but melodies come straight from God.

Quincy Delight Jones, Jr., known to his friends as “Q,” was born on Chicago’s South Side. When he was ten he moved, with his father and stepmother, to Bremerton, Washington, a suburb of Seattle. He first fell in love with music when he was in elementary school, and tried nearly all the instruments in his school band before settling on the trumpet. While barely in his teens, Quincy befriended a local singer-pianist, only three years his senior. His name was Ray Charles. The two youths formed a combo, eventually landing small club and wedding gigs.

At 18, the young trumpeter won a scholarship to Berklee College of Music in Boston, but dropped out abruptly when he received an offer to go on the road with bandleader Lionel Hampton. The stint with Hampton led to work as a freelance arranger. Jones settled in New York, where, throughout the 1950s, he wrote charts for Tommy Dorsey, Gene Krupa, Sarah Vaughan, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Dinah Washington, Cannonball Adderley and his old friend Ray Charles.

By 1956, Quincy Jones was performing as a trumpeter and music director with the Dizzy Gillespie band on a State Department-sponsored tour of the Middle East and South America. Shortly after his return, he recorded his first album as a bandleader in his own right for ABC Paramount Records.

In 1957, Quincy settled in Paris, where he studied composition with Nadia Boulanger and Olivier Messiaen, and worked as a music director for Barclay Disques, Mercury Records’ French distributor. As musical director of Harold Arlen’s jazz musical Free and Easy, Quincy Jones took to the road again. A European tour closed in Paris in February 1960. With musicians from the Arlen show, Jones formed his own big band, with 18 artists — plus their families — in tow. European and American concerts met enthusiastic audiences and sparkling reviews, but concert earnings could not support a band of this size, and the band dissolved, leaving its leader deeply in debt.

After a personal loan from Mercury Records head Irving Green helped resolve his financial difficulties, Jones went to work in New York as music director for the label. In 1964, he was named a vice president of Mercury Records, the first African American to hold such an executive position in a white-owned record company.

In that same year, Quincy Jones turned his attention to another musical area that had long been closed to blacks — the world of film scores. At the invitation of director Sidney Lumet, he composed the music for The Pawnbroker.

Following the success of The Pawnbroker, Jones left Mercury Records and moved to Los Angeles. After his score for The Slender Thread, starring Sidney Poitier, he was in constant demand as a composer. His film credits in the next five years included Walk Don’t Run, In Cold Blood, In the Heat of the Night, A Dandy in Aspic, MacKenna’s Gold, Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice, The Lost Man, Cactus Flower, and The Getaway. To date he has written scores for 33 major motion pictures.

For television, Quincy wrote the theme music for Ironside (the first synthesizer-based TV theme song), Sanford and Son, and The Bill Cosby Show. The 1960s and ’70s were also years of social activism for Quincy Jones. He was a major supporter of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Operation Breadbasket, an effort to promote economic development in the inner cities. After Dr. King’s death, Quincy Jones served on the board of Rev. Jesse Jackson’s People United to Save Humanity (PUSH).

An ongoing concern throughout Jones’s career has been to foster appreciation of African American music and culture. To this end, he helped form IBAM (the Institute for Black American Music). Proceeds from IBAM events were donated toward the establishment of a national library of African American art and music. He is also one of the founders of the annual Black Arts Festival in Chicago. In 1973, Quincy Jones co-produced the CBS television special Duke Ellington, We Love You Madly. This program featured such performers as Sarah Vaughan, Aretha Franklin, Peggy Lee, Count Basie and Joe Williams performing Ellington’s music. Jones himself led the orchestra.

The film composer/activist/TV producer had not abandoned his career as a recording artist, however. From 1969 to 1981, he recorded a series of chart-busting Grammy-winning albums, fusing a sophisticated jazz sensibility with R&B grooves and popular vocalists. These included Walking in Space, Gula Materi, Smackwater Jack, and Ndeda. In 1973, You’ve Got It Bad, Girl marked his recording debut as a singer. Its follow-up, Body Heat, sold over a million copies and stayed in the top five on the charts for six months.

This extraordinary streak almost came to a sudden end in August 1974, when Jones suffered a near-fatal cerebral aneurysm — the bursting of blood vessels leading to the brain. After two delicate operations, and six months of recuperation, Quincy Jones was back at work with his dedication renewed. The albums Mellow Madness, I Heard That and The Dude finished out his contract with A&M Records as a performer, but new challenges lay just ahead.

Jones went back into the studio to produce Michael Jackson’s first solo album, Off the Wall. Eight million copies were sold, making Jackson an international superstar and Quincy Jones the most sought-after record producer in Hollywood. The pair teamed up again in 1982 to make Thriller. It became the bestselling album of all time, selling over 30 million copies around the globe and spawning an unprecedented six Top Ten singles, including “Billie Jean,” “Beat It” and “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’.”

His debut as a filmmaker occurred in 1985 when he co-produced Steven Spielberg’s adaptation of Alice Walker’s The Color Purple. The film won 11 Oscar nominations and introduced Whoopi Goldberg and Oprah Winfrey to movie audiences.

In 1993, Quincy Jones and David Salzman staged the concert spectacular “An American Reunion” to celebrate the inauguration of President Bill Clinton. The two impresarios decided to form a permanent partnership called Quincy Jones/David Salzman Entertainment (QDE), a co-venture with Time-Warner, Inc.

The company, in which Jones serves as Co-CEO and Chairman, encompasses multimedia programming for current and future technologies, including theatrical motion pictures and television. QDE also publishes Vibe magazine and produced the popular NBC-TV series Fresh Prince of Bel Air. At the same time, Jones runs his own record label, Qwest Records, and is Chairman and CEO of Qwest Broadcasting, one of the largest minority-owned broadcasting companies in the United States. Throughout the 1990s, he continued to produce hit records, including Back on the Block and Q’s Jook Joint.

The all-time most nominated Grammy artist, with a total of 80 nominations and 28 awards, Quincy Jones has also received an Emmy Award, seven Oscar nominations, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award.

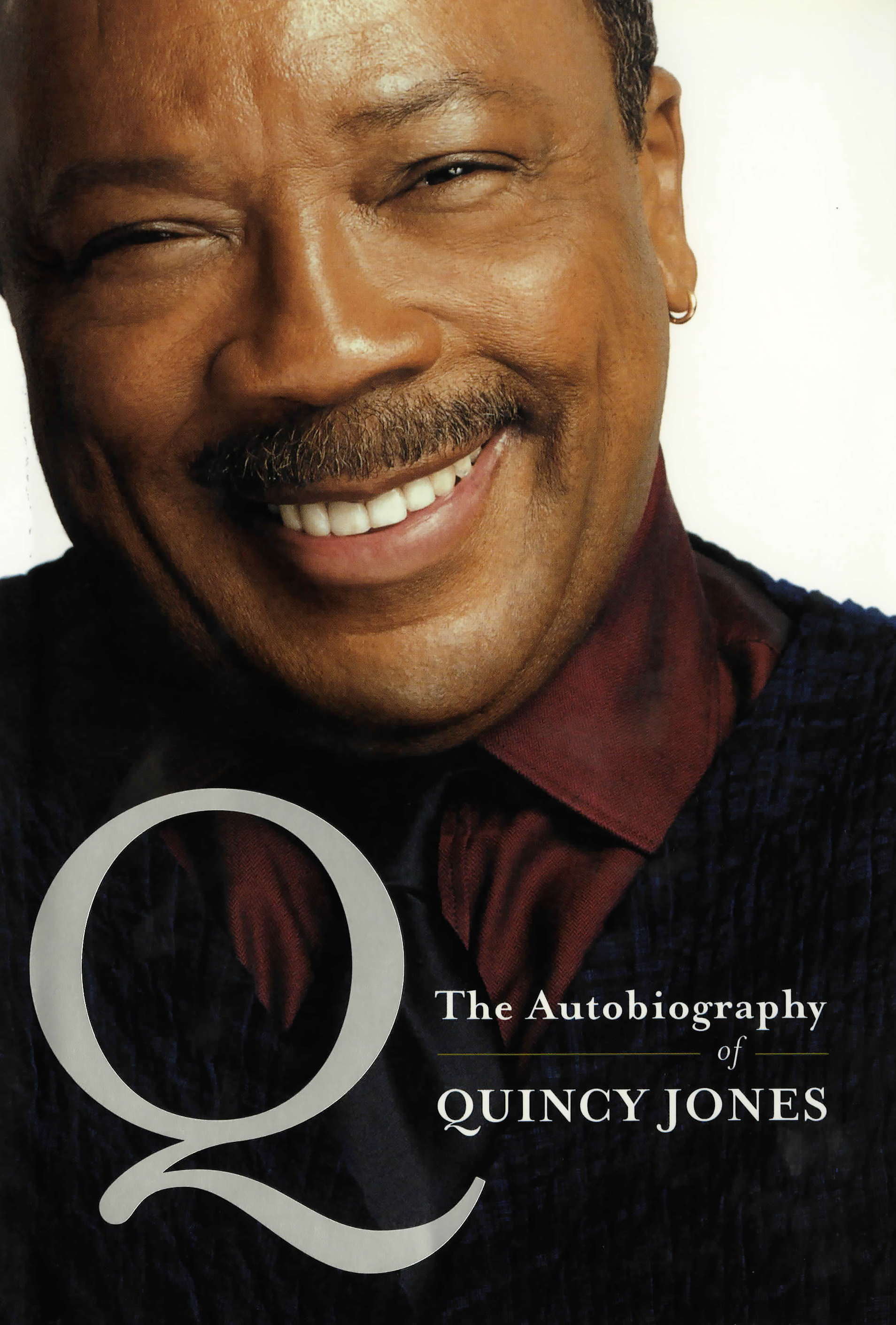

His life and career were chronicled in 1990 in the critically acclaimed Warner Bros. film Listen Up: The Lives of Quincy Jones. In 2001, he published Q: The Autobiography of Quincy Jones. A richly illustrated volume of reflections on his life and career, The Complete Quincy Jones: My Journey & Passions, followed in 2008.

Two years later, he released his first new album in 15 years, Soul Bossa Nostra, featuring an all-star cast of contemporary pop, R&B and hip-hop artists in what Quincy Jones calls “a family celebration.” In 2013, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Quincy Jones entered yet another new field of endeavor in 2017, lending his name to a new exchange-traded investment fund (ETF), the Quincy Jones Streaming Music, Media & Entertainment ETF. The fund, sub-advised by Vident Investment, is among the first to license the name of a well-known figure from the world of arts and entertainment to attract investors in the booming ETF market.

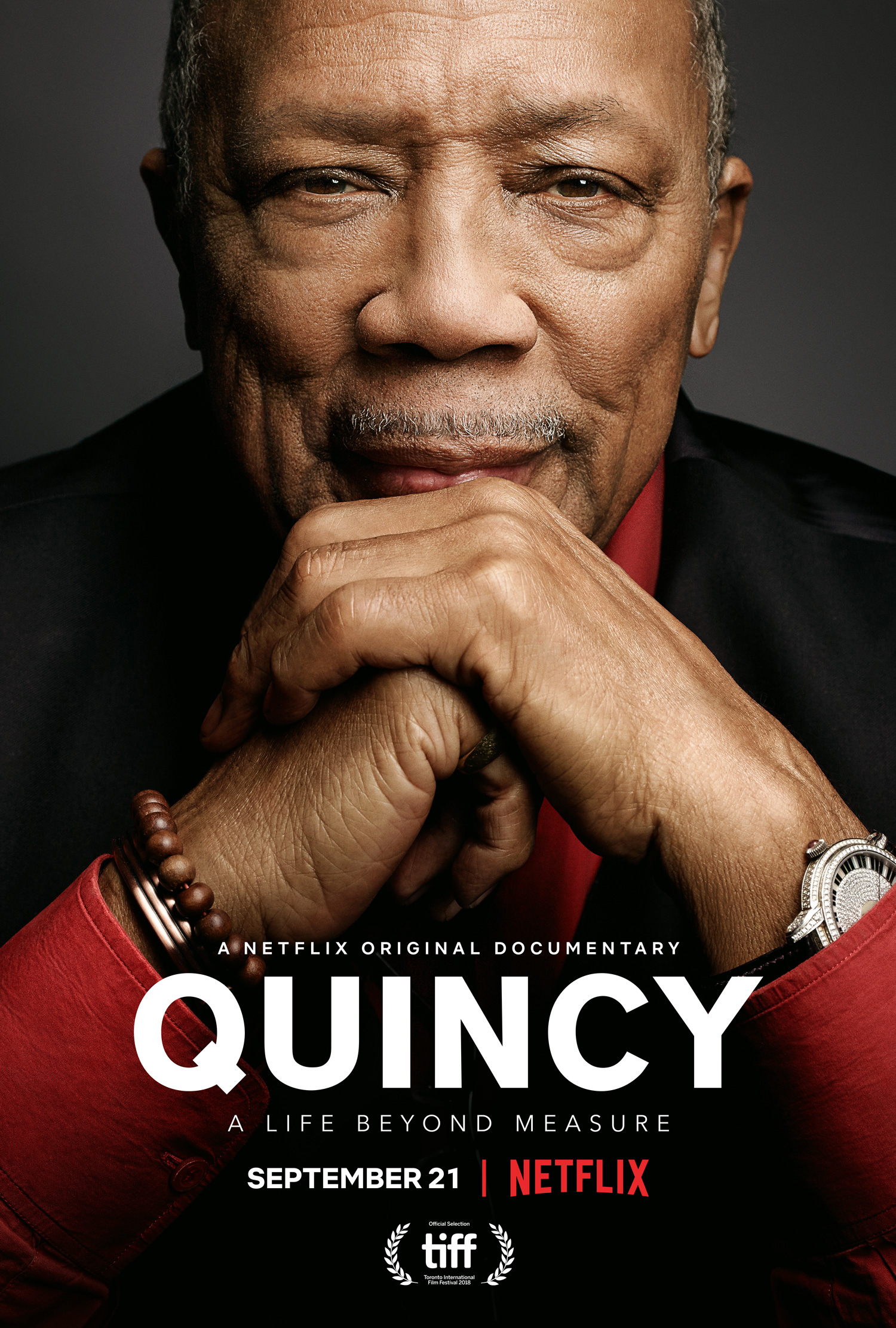

In 2018, Quincy Jones was the subject of a feature-length documentary on his life and work — Quincy. Distributed by Netflix, the film was written and directed by his daughter, actress and filmmaker Rashida Jones, who carries on her father’s legacy of artistry and social activism. At the 2019 Grammy Awards, the film was honored as the Best Music Film of the Year. Quincy Jones has now received 28 Grammy Awards, more than any other living artist.

“I think African music is so powerful, and probably governs the rhythm of every music in the world, because it’s taken straight from nature. You know that the birds did not imitate flutes. It’s the reverse. And thunder didn’t imitate the drums. It was the reverse. And so, the elements of nature, what it comes from, that’s the most powerful force there is.”

Shuffling pop, soul, hip-hop, jazz, classical, African and Brazilian music into unique and extraordinary fusions, Quincy Jones has also been dubbed “a master inventor of musical hybrids.” The list of additional titles he has garnered includes: stage performer, composer, arranger, conductor, instrumentalist, actor, record producer, motion picture and television producer, record company executive, magazine publisher and social activist. His remarkable versatility is paralleled only by the number of successes he has claimed.

Jones’s career began with the music of the post-swing era and continues through today’s multimedia digital technology in the recording, film and television worlds. First publicly recognized in the 1950s as a young trumpeter with the Lionel Hampton and Dizzy Gillespie bands, today he stands alone as the most nominated Grammy artist of all time, with 80 nominations. To date, he has received 28 Grammy Awards, more than any other living artist. He has composed over 50 major motion picture and television scores, earned international acclaim as producer of the historic We Are the World recording (the bestselling single of all time) and produced the bestselling album in the history of the recording industry, Michael Jackson’s Thriller.

After over 50 years in show business, Quincy Jones has reached the essence of many different artists, and in doing so he has reached the essence of art itself: the ability to touch people’s feelings and emotions.

(Quincy Jones was first interviewed by the Academy of Achievement on June 3, 1995 at the Academy program in Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia and again on October 28, 2000 at the Summit in London. The following transcript draws on both interviews.)

You’ve said you had no musical training when you first met Ray Charles as a teenager in Seattle. Is that right?

Quincy Jones: No training at all at that time, but after that I was probing and probing and waking up Ray Charles when he came to town, waking him up at 5:00 or 6:00 o’clock in the morning.

I was 14 years old when Ray [Charles] came to town from Florida. He wanted to get away from Florida and he asked a friend of his — because he had sight until he was seven — to take a string from Florida and get him as far away from Florida as he could get and boy, Lord knows, that’s Seattle! If you go any further you’re in Alaska and Russia! So Ray showed up, and he was, at 16 years old, and he was like — God! You know! He had an apartment, he had a record player, he had a girlfriend, two or three suits. When I first met him, you know, he’d invite me over to his place. I couldn’t believe it. He was fixing his record player. He’d shock himself because there were glass tubes in the back of the record player then, and the radio. And, I used to just sit around and say, “I can’t believe you’re 16 and you’ve got all this stuff going,” because he was like he was 30 then. He was like a brilliant old dude, you know. He knew how to arrange and everything. And he used to — taught me how to arrange in Braille, and the notes. He taught me what the notes were because he understood. He said, “A dotted eighth, a sixteenth, that’s a quarter note,” and so forth. And, I’d just struggle with it and just plowed through it.

So was Ray Charles your first music teacher?

Quincy Jones: He was one of them. Bumps Blackwell was too and a barber named Eddie Lewis. Then we finally got a trumpet teacher named Frank Waldron. He was an African American with a bald head, and he used to wear striped pants, like the guys in the English Parliament. He looked like he stepped out of the Harlem Renaissance. He had a little flask of gin, and every night he’d take a sip three or four times and he said, “Let me hear you play something.” He was from a legit school of trumpet players, like Rafael Mendez. We had our be-bop thing, our little look and the swagger, and our fingers all the way over there — so incorrect! I played “Stardust” just like I played it in the nightclubs, because we were playing in nightclubs when we were 13 and 14.

How did you learn to play in the first place?

Quincy Jones: I just started playing. Just do it. Just blow in it and sound bad for about a year and then make it sound a little bit better, and you get a little band together, and then you get a few jobs. You take four guys that sound half bad, but if they’re 25 percent each, they can give 100 percent, you know? There were four guys, including Charlie Taylor and Buddy Catlett; we got together and we practiced every day.

So how did you start performing, as a working musician?

Quincy Jones: In 1947 we got our first job for seven dollars, and the year after that we played with Billie Holiday, you know, with the Bumps Blackwell-Charlie Taylor band, and our confidence was building, because we danced and we sang and we played all — we played modern jazz, we played schottisches, pop music at the white tennis clubs: “Room Full of Roses,” and “To Each His Own,” and all those things. And we played the black clubs at ten o’clock, and played rhythm and blues, and for strippers, and we’d do comedy and everything else. At 3:00 o’clock in the morning we’d go down to Jackson Street in the red light district and play be-bop free all night because that was really what we really wanted to play, like Charlie Parker, Miles Davis and Dizzy and all those people, and they’d come through town. And in the following year Bobby Tucker — who was Billie Holiday’s musical director — came back, and he liked what we did evidently, and we played with Billy Eckstine, and then Cab Calloway came through and we opened for Cab Calloway. So, our confidence was very strong.

I had written a suite called “From the Four Winds” that the Seattle University band played before I got out of high school. We came in from the high school and played it with the university band. They put our picture on the front page of the Seattle University paper. Lionel Hampton had heard about this “Four Winds” thing and he asked me to join the band when I was 15. I hurried up and got on the bus. I didn’t want to ask my parents or anybody. I wouldn’t take a chance of losing it. I just shut up like a little mouse and everybody got on the bus and it was almost ready to take off and Gladys Hampton got on and said, “What’s that child doing on this bus?” And I said, “Oh, my God!” She said, “Lionel, get that boy off. That’s a child. That’s not a grown-up. Put him back in school.” And she said, “I’m sorry, son, but, you know, you’re too young. Go back to school.” I was destroyed, so she said, “We’ll talk about it later.”

My heart was broken. I got a scholarship to Seattle University and I was writing arrangements for singers and everybody. But the music course was too dry and I really wanted to get away from home.

We made $17 a night. You have to learn how to do that, too. And they had wash-and-wear shirts to carry in the sax case. I got one of those. And when they’d get in a hotel, we’d go to Father Divine’s for 15 cents, you know, have the stool and stuff and say “Peace” when you go in the door. You’d fold up your pants and put them underneath the mattress. We couldn’t afford to get them pressed. And you’d put your coat in the bathroom, turn the steam on, hang your wash-and-wear shirt there. Wash your handkerchief, put it on the mirror, and the next morning it’s dry and you pull it off and it’s already pressed, you know. And so I learned all these things from the guys that had been out there and I just watched. I really paid attention to what was going on, one thing leads to another and you grow.

While I was in Boston, sure enough this lady, Janet Thurlow, who was in the Lionel Hampton band, kept reminding them of me, and they called me one day and I was so happy. I’m telling you, you have no idea. I told the Dean there, I said, “I’ll be back.” He knew I’d never be back, once I got out there with professional musicians.

The band was working 70 one-nighters in a row all through the South, doing 700 miles a night, with these guys that had been out there 30 years. I used to watch the old guys. I really respected their wisdom.

There was a guy named Bobby Plater who wrote “The Jersey Bounce.” He was like the musical director, a wonderful man. He was kind to me, too. A lot of the old guys wouldn’t talk to me because I was an arranger and a trumpet player, and they felt threatened. I guess that happens. But I used to watch him, and the guitar player who had been out there 30 years, and they knew all the cheap hotels.

I wanted to get out of that house. I didn’t want to be there. Eight kids and a stepmother, and I just wanted to be out of there. So, when I got a scholarship from Boston to the Schillinger House, which is now the Berklee School of Music, I couldn’t wait to get out of there. And my aunt sent me a ticket by train to go there. I stopped in Chicago and I went into Boston at night — the most terrifying thing I’ve ever seen in my life. Because it was pitch black and you get there and you’ve got your trumpet and this little bag, your bag of clothes, not much, no place to stay but I had a scholarship and that was sort of a blanket, a security blanket I could hold on to. And, one thing led to another. I walked around the neighborhood to try to find out where I could stay. I got a place for $10.

What was it like for a black kid traveling in America at that time?

Quincy Jones: Killer. Absolute killer. I had no idea because in Seattle, even though there was racism there, it was more on the level of a lower education basis, sailors and so forth. We just had our 50-year reunion at Garfield High School this year. That is the school that America dreams in its wildest dreams that they will have 50 years from now. That school had everything, Filipino, Jewish, black, Chinese, everything, all together and it was no big deal. I married one of the girls from that school. She talks about getting thrown out of all the top sororities and everything else, and I didn’t even know that until 50 years later, all the stuff that was going on. But regardless, that was one of the most progressive schools in America in 1947 and ’48.

Then we hit the road and we’d get to places like Texas. This is when every place had “white” and “colored” to wait in the bus stations and the water fountains, all over America. You couldn’t stay in a white hotel anywhere. We played dances in New Orleans, and they’d have chairs straight down the middle of the thing with chairs to go both ways, white on this side and that side. Then the places in North Carolina and South Carolina, they’d have $2.50 and $3.50 general admission for the black people, white spectators $1.50. I still have the signs, you know. And they’d sit upstairs and drink and watch the black people dance, you know. It was unbelievable. We played juke joints and people would get shot and we’d go through Texas. We always had a white bus driver because we couldn’t stop in the restaurants. And sometimes we’d see effigies — like black dummies — hanging by nooses from church steeples in Texas. That’s pretty heavy, on the church steeple, and they’ve got a black dummy, which means “Don’t stop. Don’t even think about coming here,” and the bus kept moving. And then they’d finally get to places where we’d get the driver — the white driver would go in and get food for the band. And sometimes in Newport News we slept — I remember Jimmy Scott and I slept in a funeral parlor where the bodies were. There was no hotel so this guy said, “I’ve got a place. You can stay here these two days.” We got $17 a night. You’re not thinking about some suite at the Waldorf.

How does that affect you psychologically?

Quincy Jones: It’s painful. It’s a killer. It slaps your dignity just right. I loved the idea of these proud, dignified black men, and I saw the older ones wounded, and it wounded me ten times as much because I couldn’t stand seeing them hurt like this. I knew their mentality, their sense of humor, their wit, their intelligence and everything, totally aware of it, and I’d see people with one-tenth of this, trying to degrade them, trying to be a giant and make a midget out of them to feel bigger. I saw it over and over and over again. When you’re unified you get a sense of humor about it or else.

We had confrontations all the time. Please! We had police run us out of town many a time, you know. And, they’d have the joke. You go in a place, they’d always say, “We don’t serve niggers here.” We’d say, “That’s cool. We don’t eat them.”