The higher the mountain, less emotions. There is no place for emotions. There’s only the decision, 'Now finally, I am able — I am free — to go down.' We force ourselves against our instinct of survival, our strongest instinct. An egotistical instinct is our instinct of survival. We have it.

Reinhold Messner was born in South Tyrol, a mountainous region of Northern Italy. The town where Messner was born is known as Brixen in German and Bressanone in Italian. He grew up in the neighboring municipality of Vilnöß, called Funes in Italian. He was one of nine children — eight boys and one girl — of a village schoolteacher who was himself an enthusiastic mountain climber. South Tyrol was formerly part of Austria and the majority of the population is still German-speaking. The Dolomite mountain range, a southern extension of the Alps, runs through the region, and at an early age, Messner began climbing mountains with his family. At age five, he had already ascended a peak of 3,000 meters. At 13, he was attempting difficult peaks in the Dolomites with his younger brother Günther.

The Messner brothers pursued the traditional climbing practice known as alpinism, in which climbers travel with a minimum amount of equipment, rather than the “expedition style” in which advance teams plant caches of supplies along the more accessible stages of the route. As a teenager, Reinhold Messner subjected himself to a grueling regimen of physical exercise to build strength and agility for the increasingly ambitious climbs he aspired to.

Reinhold and Günther were inspired by the example of Hermann Buhl. The Austrian Buhl was among the first mountaineers to apply alpine techniques to the Himalayas, the highest mountains on Earth. Buhl made history in 1953 when he reached the summit of Nanga Parbat, a Himalayan peak that had claimed the lives of 31 climbers before him. In the book he wrote about his experience, Buhl decreed that the southern — or Rupal — face of the mountain, a sheer wall of rock and ice, could never be climbed by a human being. To Reinhold Messner, this became an irresistible challenge.

In 1953, Hermann Buhl, alone and without supplementary oxygen, made the first ascent of Nanga Parbat – the ninth-highest mountain in the world, and the third 8,000-meter peak to be climbed, following Annapurna and Everest. Starting in his teens, Messner worked as a guide for less experienced mountaineers. By his 20th birthday, he had led over 500 ascents in the Dolomites. Over the course of his career, he would identify as many as 700 new routes to the range’s peaks. Reinhold Messner studied architectural engineering at the University of Padua but spent much of the academic year climbing the campus’s brick walls with his brother to refine their climbing skills. In his 20s, Reinhold drew attention in the mountaineering community for reaching some summits from previously untried approaches, and others in winter, when conditions are most difficult. In a few years, he had climbed the highest peaks in the Dolomites and the Swiss Alps, many in the company of his brother. He supported himself by teaching math in a local school while Günther worked in a bank. On vacations, Reinhold traveled to the Peruvian Andes and met other members of the international mountaineering fraternity, but his heart was still set on the Himalayas.

In 1970, Reinhold and Günther Messner set out to meet the challenge Hermann Buhl had set years before. They joined a German team attempting to climb the southern approach — the Rupal Face — of Nanga Parbat in Pakistan, a 15,000-foot wall regarded as the most difficult ascent in the world. For 40 days, the team labored up the treacherous face of the mountain. Alone among their party, Reinhold and Günther reached the summit but were unable to return by the way they had come. Exhausted and delirious, they attempted to descend by the mountain’s western — or Diamir — face, and Günther disappeared in an avalanche.

Unable to find his brother, Reinhold was rescued six days after reaching the summit, but severe frostbite required the amputation of most of his toes. He eventually recovered from his injuries, but with his maimed feet he was unable to continue the style of rock climbing he had mastered in the Dolomites. Undeterred, he decided to pursue climbing at the highest altitudes, where surfaces of solid ice posed a different challenge than climbing on bare rock.

In the early 1970s, Messner sought new mountaineering challenges around the world, traveling to Persia, Nepal, New Guinea, Pakistan, and East Africa. With a climbing partner, Peter Habeler, he set new standards of speed in ascending some of the highest peaks of the Alps. In 1972, he reached the summit of Manaslu, in the Nepalese Himalayas, from its previously unmapped south face, although two of his fellow climbers were lost along the way. Messner returned repeatedly to Nanga Parbat, attempting to reach the summit from the Diamir Face, on which his brother had perished, hoping to find Günther’s remains, but he was repeatedly forced back by avalanches.

Climbing the world’s highest peaks requires most climbers to carry supplemental oxygen. In 1975, Messner and Habeler climbed Gasherbrum I in the Himalayas without the oxygen masks that previous Himalayan climbers depended on, the first time a peak of over 8,000 meters (more than 26,000 feet) had been climbed in the alpine style, without bottled oxygen. In 1978, Messner and Habeler set out to climb Everest without supplemental oxygen. Many mountaineers and physicians believed it was impossible for climbers to survive at the highest point on Earth without supplemental oxygen, but the pair succeeded. Reinhold Messner recounted the experience in his book Everest: Expedition to the Ultimate.

Following his success at Everest, Reinhold Messner finally succeeded in climbing Nanga Parbat singlehanded from the Diamir Face. It was the first time a solo climber had made an ascent of more than 8,000 feet from a base camp without assistance. He established a new route up the mountain, which has no climber has yet repeated. The following year, he led a team of six climbers to the summit of K2, the second tallest mountain in the world. In 1980, he achieved the most remarkable exploit of all, the first solo ascent of Everest, a feat he achieved without oxygen during the hazardous monsoon season.

Messner’s hard-won triumph on Everest brought him international renown and lucrative publishing contracts, but he continued to set extraordinary goals for himself. In 1982, he reached the top of three more Himalayan peaks — Kangchenjunga, Gasherbrum II, and the Broad Peak — becoming the first person to summit three mountains of more than 8,000 meters in a single season. At this point, Reinhold Messner had established an uncontested reputation as the world’s greatest mountaineer. The German director Werner Herzog featured Messner in his film The Dark Glow of the Mountains. In 1984, Messner climbed from Gasherbrum I to Gasherbrum II — two peaks of more than 8,000 meters — without returning to base camp. In the following years, he reached the peaks of Annapurna, Dhaulagiri, Makalu, and Lhotse. By 1986, he had climbed all 14 of the world’s peaks that stand more than 8,000 meters above sea level, an achievement entirely without precedent.

In the 1980s, the newly crowned “King of the 8,000-Meter” continued his explorations of Tibet and Bhutan, and climbed Mount Vinson in the Antarctic. In Tibet in 1988, after years of searching, he observed a rare species of bear that is the probable source of the legend of the Yeti or “abominable snowman.” Because the bear tests the snow with its forepaws before placing its hind feet, it leaves only hind leg footprints, which then appear to be those of a two-legged creature. In 1990, Messner crossed the entire continent of Antarctica — 1,740 miles — traveling over the South Pole on skis rather than with a snowmobile or dogsled. In the following decade, his travels took him from Siberia to the Andes. In 1993, he crossed Greenland on foot. The documentary film Portrait of a Snow Lion — a French-British co-production — featured Messner and his exploits.

Reinhold Messner has written dozens of books describing his experiences, including The Crystal Horizon (describing his solo ascent of Everest), as well as All Fourteen 8,000ers and My Quest for the Yeti. A passionate environmentalist, he was elected to a term representing Northeast Italy in the European Parliament as a member of the region’s Green Party. He served a full term from 1999 to 2004, advocating for conservation of the natural world, sustainable development, and a focused response to the dangers of climate change.

In the first years of the 21st century, Messner filmed a television series, Wohnungen der Götter (“Homes of the Gods”) for German television, introducing a mass audience to the spiritual traditions associated with the world’s mountains. In 2004, he crossed Mongolia’s Gobi Desert — 1,250 miles — on foot. The following year, an unprecedented heat wave melted a bank of snow and ice on the Diamir Face of Nanga Parbat, exposing the remains of Reinhold Messner’s brother Günther. For years, some veterans of the 1970 expedition had questioned Reinhold Messner’s account of his brother’s death, but the location of Günther’s body confirmed the substance of Reinhold Messner’s recollection.

In 2006, the celebrated mountaineer opened the Messner Mountain Museum, dedicated to propagating knowledge of the beauty, history and natural science of Earth’s highest places. The museum has facilities at six different locations, dealing with different aspects of mountain studies: man’s relationship with the mountains; the art and spiritual lore of the mountains; geology; the history of mountaineering on ice; the mountain peoples of Asia, Africa, South America, and Europe; and the practice of alpine-style climbing.

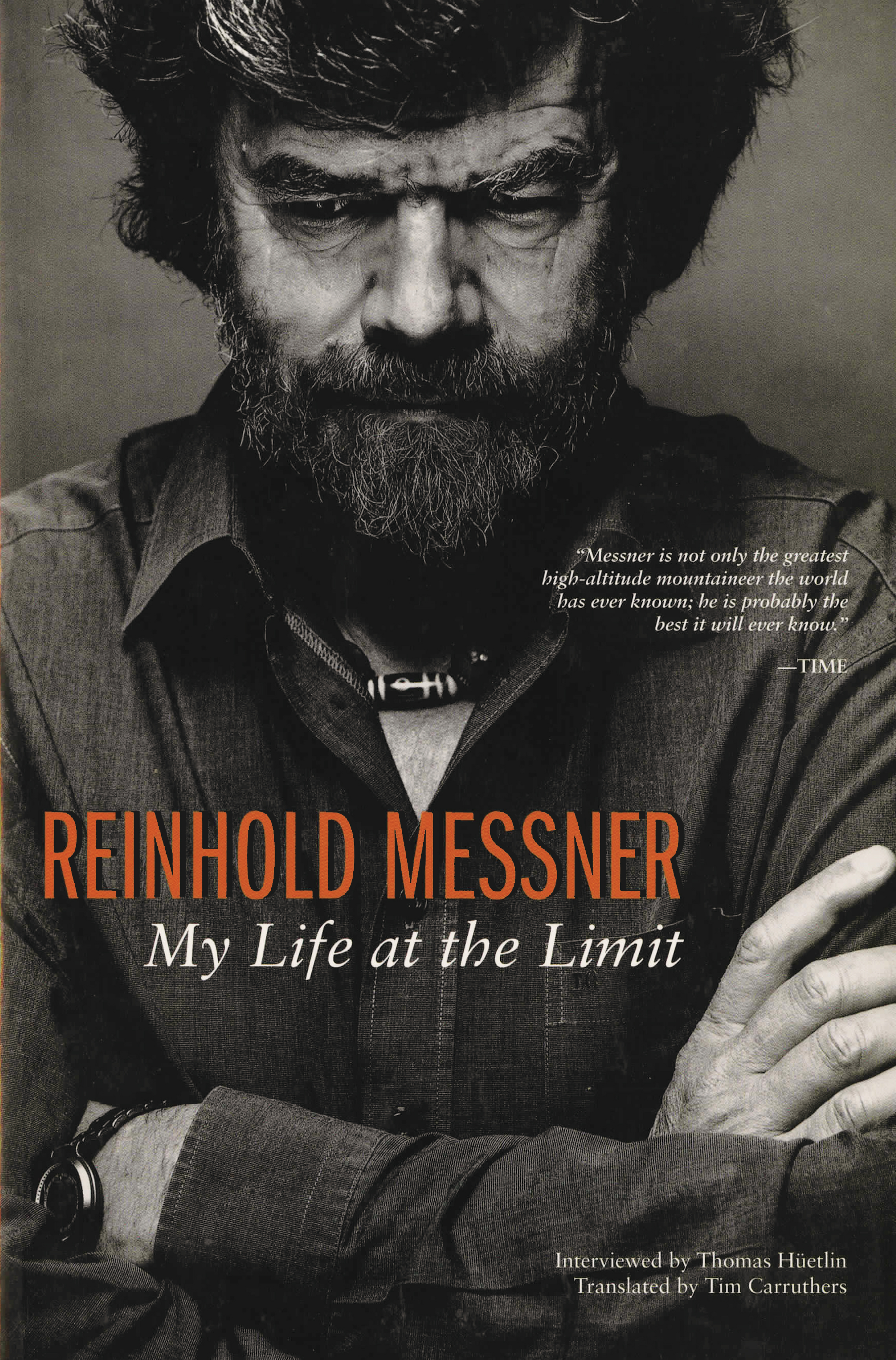

A 2010 film, Nanga Parbat, dramatized the events of the 1970 ascent. Among the more than 60 books he has published to date are The Naked Mountain; Free Spirit: A Climber’s Life; and My Life at the Limit. Now in his 70s, he no longer undertakes the feats of high-altitude endurance he performed in his youth, but he continues to enjoy an active outdoor life and is producing films to bring the glorious sights he has seen to a worldwide audience. Reinhold Messner was married to Ursula Demeter from 1972 to 1977. Since 2009, he has been married to Sabine Stehle. He has four children, at least one of whom is now following in his adventurous footsteps.

Hailed as the greatest mountaineer in history, Reinhold Messner rejects such titles, but the record of his achievement is incontestable. Time and again, he has challenged and surpassed the supposed limits of human strength, courage, and endurance, overcoming seemingly insuperable obstacles to reach the most exalted places on Earth.

A pioneer of high-altitude climbing in the Alpine style, without porters or any of the other appurtenances of expedition-style mountaineering, he is the first man in history to reach the summit of all the world’s mountains of over 8,000 meters (26,247 feet). In 1978, he and a climbing partner reached the summit of Mount Everest — the tallest mountain on Earth — without the use of supplemental oxygen, defying the conventional wisdom of mountain lore and medical science. Two years later, Messner repeated this feat singlehanded — the first man to reach the summit of Everest alone.

Since then, he has traveled on foot across the entire breadth of Antarctica, traversed the Gobi Desert of Mongolia unaccompanied, and solved the mystery of the Yeti — or “abominable snowman” — said to haunt the Himalayas. Through his books, films, and the Messner Mountain Museum in South Tyrol, Italy, he shares the majesty and wonder of Earth’s most inaccessible places and the exhilarating experience of a life lived at the limit.

There are so many firsts in your career. Why do you think you have been so successful doing things that others barely dared attempt?

Reinhold Messner: I think that I have only one thing which many other climbers do not have. I had the opportunity in my 15th year to learn naively to survive in the mountains, so it became an instinct. When I was 20, and I met famous climbers — before we went, my brothers, all of them climbed. My younger brother was an extreme climber like me. We became really top climbers. We had no opportunities to know famous climbers because we came out of a small hidden valley in the Dolomites — and seeing some other climbers but not being at least able to speak with them because we had a great respect.

But when I was 20, I met the first famous Austrian climber. He was seven years older than me, and he had the knowledge, much better than me, and we climbed together. And I learned many things from him. Maybe it was one safety fact that I survived later. And in this period, I understood quite quickly that there are perfect rock climbers, good Alps climbers, but they don’t have my instinct. They could not see from far away where is the good line, where in the rock it’s not good, when a cloud told me now the weather is getting better and better to go down. All the ideas for first climbs I did in my life, more than 100 for my expeditions, are coming all out of this head.

Where did you get these ideas for what you wanted to try next?

Reinhold Messner: After doing 15 years of climbing in the Dolomites at home— on smaller walls but also on difficult walls — I was able to do the most difficult routes in the Alps, the Mont Blanc area and the Dolomites. And I tried to do the most difficult routes. And afterwards, I went further and said, “The climb was yesterday.” Hermann Buhl and Walter Bonatti said, “This route is impossible.” And I said, “Let’s look.” For example, a typical example, when Hermann Buhl climbed Nanga Parbat in 1953, it was one of the greatest achievements ever in alpinism. In 1953, he went up on the eastern ridge — not so difficult in many parts. And he could see, in diagonal vision, the south face of Nanga Parbat. And he wrote in his book, “This wall is so steep and so high — it’s the highest wall of the world — that never anybody will do it.” And this was the motivation 17 years later to go there and try.

So many people have died on Nanga Parbat and the other peaks you’ve climbed. Why do you think you survived?

Reinhold Messner: If I would look to the most able alpinists, traditional alpinists of the last 50 years — most of them I know personally — 50 percent, exactly 50 percent died on the mountains and 50 percent survived. So this is the proof this is not ability only. This is also luck. The avalanche didn’t touch me on Nanga Parbat. I was a little bit ahead of my brother. But why? Not because I was ahead but because I was looking for the route and he was waiting to get the sign from me that “Okay, we can go further.” So it happened.

How do you overcome your limits from the day before?

Reinhold Messner: You did a good climb and you have the grade of difficulties because this is in the description. So you know, “These difficulties I can handle, I can manage.” But next time, you try to do a little bit more, a higher wall, a more difficult wall. And in the end — I went from the Alps to the Himalayas — especially because I lost my toes partly in the tragedy on Nanga Parbat, losing also my brother, and I was not able to climb anymore like before. Never ever after ’69 — this was my best year, ’68-’69, as a rock climber — I could approach the difficulties I did before. And losing this ability, I lost also interest and enthusiasm for this activity. So after a while of discussing with myself, I decided to expose myself to the high altitudes, to try to become a high-altitude climber. I was beginning by zero, learning from other ones, seeing how they handle it. And I changed the whole high-altitude alpinism.

How did that tragedy affect you?

Reinhold Messner: It affected a lot because it was the necessity to leave climbing at all or to change activity. It was the first time when I was forced — in this case, I was forced to begin a new life. And today, looking backwards, I have the feeling I had 20 years of difficult climbs on rocks, on ice, especially in the Alps. And I was on a high level when this tragedy put me out of this career of this activity. And I was beginning a new life. It was my second life in high altitude.

I learned slowly. First, I learned to be in small groups, to do difficult routes in small groups without tents, without Sherpas, without oxygen, and so on. I needed a long time to be able to climb an 8,000-meter peak solo. Because being solo, you cannot divide fear, you cannot divide the work you have to do up there. And the solo climb of Nanga Parbat in ’78 is much more important than the solo climb of Everest because it was the mountain where I learned it. And especially, I did a totally new route on a high wall on Nanga Parbat, and the first time — not only for me, for the whole climbing community — somebody did an 8,000-meter peak solo. And the problem was not a technical problem, not a logistical problem. It was a mental problem — to be able to handle, to be on the end of the world in very dangerous situations by yourself, not being able to speak with anybody, not being able to exchange experiences, not being able to divide fear. If you are together, fear is only half. If you are with one man, only half. If you are three, it’s only a third.

How do you get over the mental fear of being five miles up in the air?

Reinhold Messner: In the Alps, I had problems to do solo climbs in the night. Normally, we begin in the night. If it’s dark, the danger is not more, but we cannot see the danger. In the night, if a stone is coming, I cannot see it. I cannot escape. During the daytime, I can look — the stones coming, stone falls, very big danger — and in the last moment, I can go apart. In the night, this is not possible, so the fear is much bigger. Only in ’69, I was able to do solo climbs without anything, difficult solo climbs. Also, bivouacking, sleeping in the middle of the wall. But on an 8,000-meter peak, it’s not only night, it’s not only one night up there. It’s a few nights. You are much more away from safety. We human beings are all made for searching for safety. In the last 10,000 years, human beings did only work for growing safety. In the cities, in communities, in the states, and so on. I don’t think that they really found more safety because now we have a technology which is able to kill us easily, all of us.

When you were at the base of Mount Everest, preparing for the first solo ascent, what was going through your mind?

Reinhold Messner: When I was beginning the solo ascent of Mount Everest, it was after two and a half months being there — because I tried just a month after reaching the base camp, but it was monsoon time. So many snow was in the mountain — very big danger for avalanches. So at 7,000 meters, I decided to go down. I went further north because there the monsoon could not reach the mountains, and I could still train and acclimatize. And when the monsoon stopped for a while — it was a monsoon break — I went back to the base camp. I was prepared mentally. I was prepared physically perfectly, and I started being able, with my rucksack, to be out dark [sic], self-sufficient for more or less ten days.

What was in your rucksack?

Reinhold Messner: Everything to survive: a cooker for melting snow; some food but not many; a small tent; a mattress; a meter of rope, two meters of rope, to belay myself for a moment on the mountains; a piton, a rock piton; and an ice tool. Naturally, the ice axe, I had in my hand, the crampons I had on my shoes.

Did you bring anything for good luck?

Reinhold Messner: No, no, no. I’m not believing in these things.

How much did it weigh?

Reinhold Messner: More or less 20 kilos.

It’s hard to imagine how dark and cold it must get.

Reinhold Messner: I started in darkness — but only the first night — because from the base camp onwards, I knew more or less the terrain. So I could start at midnight, and I had a headlamp, and I could orientate. But higher up, where I did not go before, I went only when the daylight was coming. I was melting snow in the tent. The most important thing up there is that we are drinking because we lose a lot of humidity and water with our very difficult, very strong breath. We are breathing like dogs up there, running dogs. We are hyperventilating. You have to do it because there’s less oxygen.

In reality, the pressure in the air is much less than at home. And on the Everest, this is the limit people can stay on. And I could not take oxygen bottles. I would never be able to carry them by myself. You have to know that in the ‘70s, the oxygen equipment for one man on Everest had the weight of 50 kilos.

So they needed a lot of helpers to bring all this stuff up there. And the first expeditions, when the British and Americans went — and also the Indians, in the ‘50s and the ‘60s, went to Mount Everest — they needed hundreds of porters. They needed tons and tons of materials because also, for the porters which you use, and they help you higher up, you need logistics. You need tents, and you need food, and you need cookers, and so on. And if you go alone, you need only the minimum of necessity, but you have to learn to handle it. And the problem is not a technical one. The north side of Mount Everest is not difficult for a good climber. You can fall also there, but only if you are really stupid, you can fall there.

When you keep going higher and higher and you’re over 8,000 feet up, what’s it like to breathe in that thin air?

Reinhold Messner: The thin air makes, first of all, that you are becoming slower and slower. The higher we go, less pressure is in the air, so no more oxygen is coming to our energy in the blood. And the sugar in the blood is the energy. We need oxygen to burn it, like to burn wood. If you go at 8,000 meters, you cannot make fire with wood. It’s not possible. There’s not any more burning. The oxygen is missing. And if there is not enough oxygen for your energy, which you have in your circulation of blood, you are doing one step and you do a rest, and another step and you do a longer rest, another step and the longer rest again. So you’re becoming infinite slowly.

How does it affect you mentally?

Reinhold Messner: You’re becoming — not without willpower, but with less and less and less willpower. Also, your capacity to decide. Decisions are very important, what you do, go left, right, go down.

How do you overcome that?

Reinhold Messner: You’re like a zombie up there. Only if you know to handle mountaineering like in sleep, or the same as in sleep, you are able to survive up there. So you need a long, long experience.

When you get to the highest point on Earth, what does it feel like? What emotions do you feel?

Reinhold Messner: The higher the mountain, less emotions. There is no place for emotions. There’s only the decision, “Now finally, I am able — I am free — to go down.” We force ourselves against our instinct of survival, our strongest instinct. An egotistical instinct is our instinct of survival. We have it. Who is telling me that he’s not egotistical is sick. We are all egotistical. And the human race is still alive because we are egotistical. Otherwise, I would do the first mistake and I would die out there. This instinct is keeping alive my body, my mind. But I go against my instinct higher and higher. My instinct is, in the last part, every step, saying, “Let it go down. It is too dangerous. You’ll go more and more in danger.” And on the summit, we are far, far away, farthest away from safety. So there is only the necessity, an inner necessity given us by this instinct of survival to go back.