I think that without imagination we can go nowhere. And, imagination is not something that's just restricted to the arts. Every scientist that I have met who has been a success has had to imagine. You have to imagine it’s possible before you can see something.

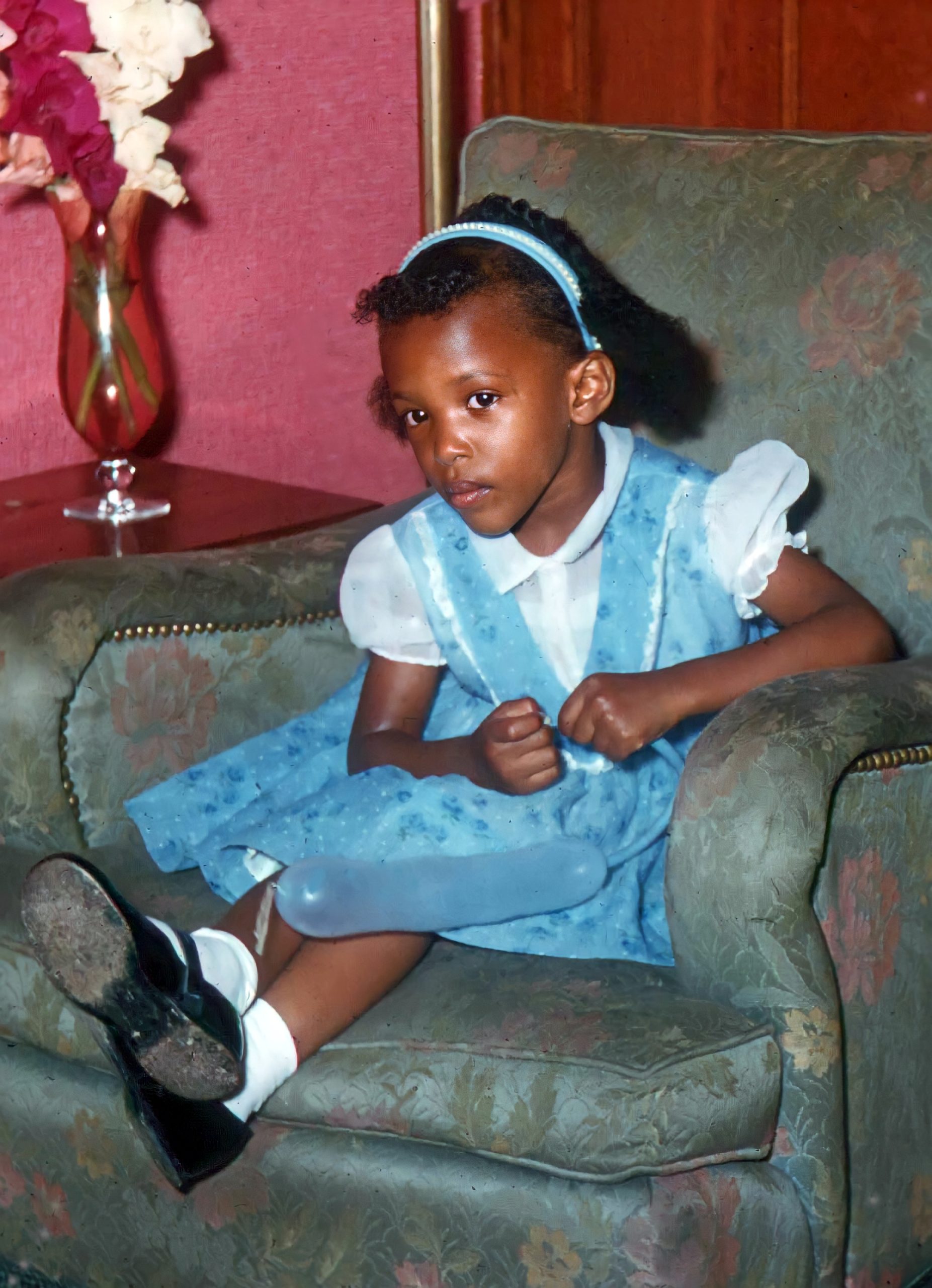

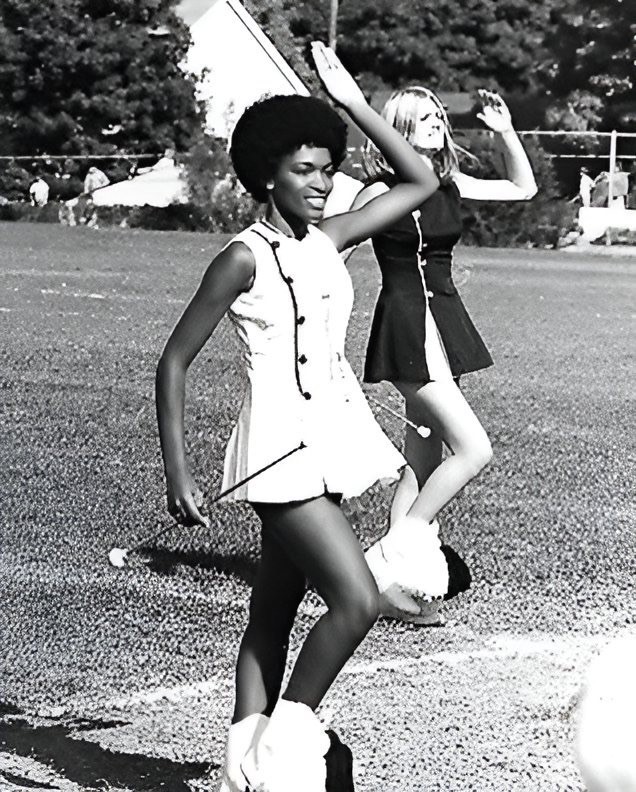

Rita Dove was born in Akron, Ohio. Her father, Ray A. Dove, was a chemist, and a pioneer of integration in American industry. Both of her parents encouraged persistent study and wide reading. From an early age, Rita loved poetry and music. She played cello in her high school orchestra, and led her high school’s majorette squad. As one of the most outstanding high school graduates of her year, she was invited to the White House as a Presidential Scholar.

At Miami University in Ohio, she began to pursue writing seriously. After graduating summa cum laude with a degree in English in 1973, she won a Fulbright Scholarship to study in Germany for two years at the University of Tubingen.

She then joined the famous Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa, receiving her master’s degree in 1977. At Iowa, she met another Fulbright scholar, a young writer from Germany named Fred Viebahn. They were married in 1979. Their daughter, Aviva, was born in 1983. From 1981 to 1989, Dove taught creative writing at Arizona State University. Appearances in magazines and anthologies had won national acclaim for Rita Dove before she published her first poetry collection, The Yellow House on the Corner, in 1980. It was followed by Museum (1983) and Thomas and Beulah (1986), a collection of interrelated poems loosely based on the life of her grandparents.

Thomas and Beulah won the 1987 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. In 1993, Rita Dove was appointed to a two-year term as Poet Laureate of the United States and Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. She was the youngest person, and the first African American, to receive this highest official honor in American letters. In the fall of 1994, she read her poem Lady Freedom Among Us at the ceremony commemorating the 200th anniversary of the U.S. Capitol.

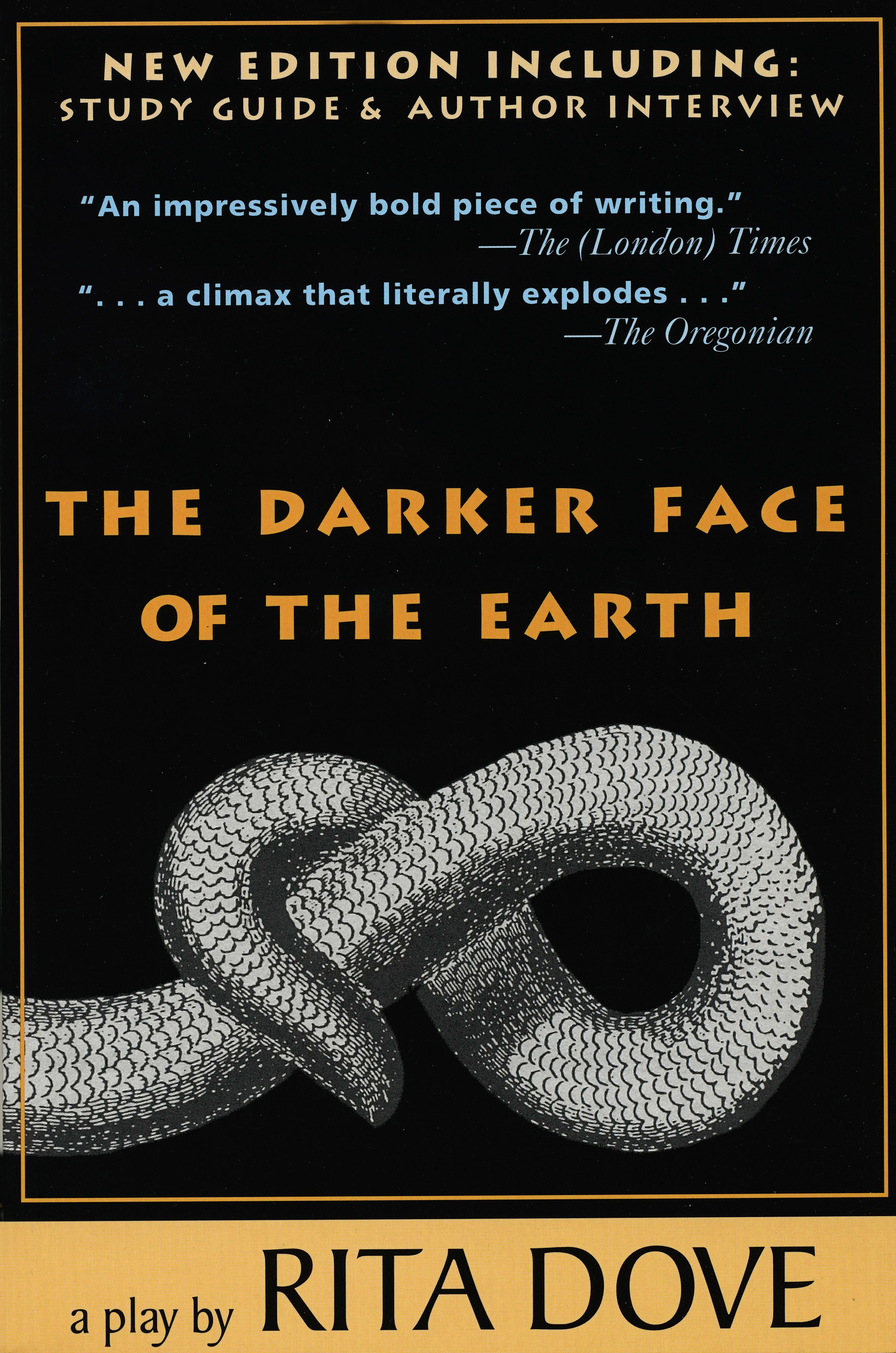

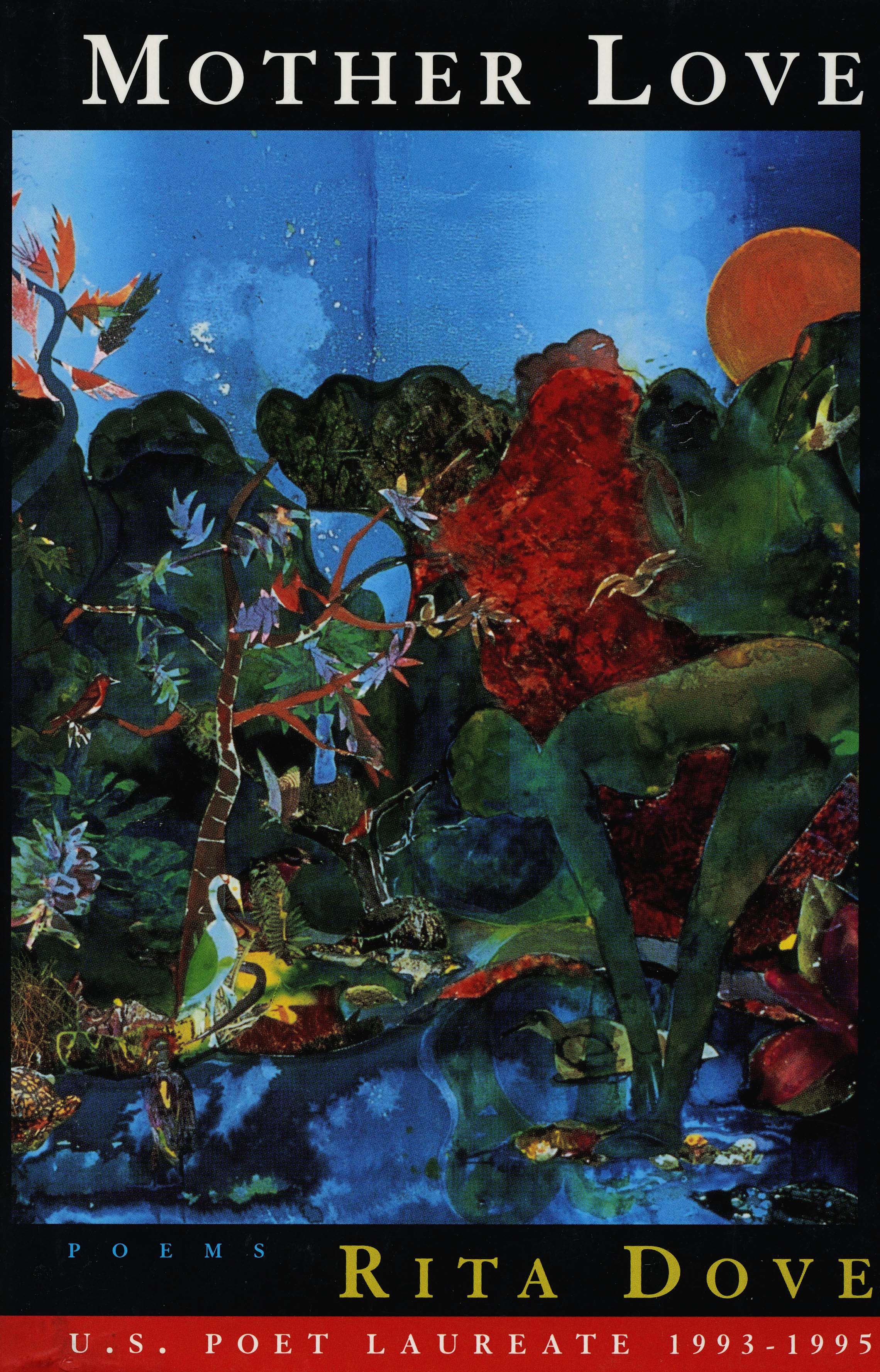

Other publications by Rita Dove include a book of short stories, Fifth Sunday, the poetry collections Grace Notes, Selected Poems and Mother Love, and the novel Through the Ivory Gate. Her verse drama, The Darker Face of the Earth, had its world premiere at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in 1986. Another production of the play appeared at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington D.C. in 1997.

Dove has brought her poetry to television audiences through her appearances on CNN and NBC’s Today Show. Public Broadcasting has devoted an hour-long primetime special to her life and work. She has shared television stages with Charlie Rose, Bill Moyers and Big Bird. On radio, she has hosted a National Public Radio special on Billie Holliday, and has been a frequent guest on Garrison Keillor’s Prairie Home Companion.

She joined former President Jimmy Carter to welcome an unprecedented gathering of Nobel Laureates in Literature to Atlanta, Georgia for the Cultural Olympiad, held in conjunction with the 1996 Olympic Games. That same year, a symphonic work for orchestra and narrator — “Umoja — Each One of Us Counts,” — was performed at Atlanta’s Symphony Hall with Rita Dove’s text performed by former Mayor and U.N. Ambassador Andrew Young.

When the Library of Congress celebrated its bicentennial in 2000, Dove served the Library again as “special consultant in poetry.” A longtime resident of Virginia, she served as the state’s poet laureate from 2004 to 2006.

Dove’s lifelong interest in music has taken other forms. She has provided text for works by composers Tania Leon, Bruce Dolphe and Alvin Singleton. Her song cycle, Seven for Luck, with music by John Williams, was featured on a PBS television special with the Boston Symphony. In 2009, she published Sonata Mulattica, a book-length cycle of poems telling the story of the 19th century African-European violinist George Polgreen Bridgetower and his turbulent friendship with Ludwig van Beethoven.

In 2011, Rita Dove was presented with the National Medal of Arts by President Barack Obama. In the same year, Dove edited The Penguin Anthology of 20th Century American Poetry. When a number of critics objected to her inclusion of some lesser-known poets at the expense of more familiar names, Rita Dove defended her choices vigorously in print and in television interviews. In 2014, Dove was the subject of a documentary film, Rita Dove: An American Poet. She received the 2015 Poetry and People International Prize in Guangdong, China and the 2016 Stone Award for Lifetime Achievement. To date, 25 honorary degrees have been bestowed upon Rita Dove, most recently in 2014, by Yale University.

Rita Dove is Commonwealth Professor of English at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, where she and her husband reside. In her spare time, she studies classical voice and practices the viola da gamba, a 17th-century forerunner of the modern cello. A comprehensive edition of her verse Collected Poems 1974-2004 was published in 2016.

“I didn’t know writers could be real live people, because I never knew any writers.”

Today, all Americans who love poetry may feel they know Rita Dove. In addition to her writing, and her television, theater and music projects, she holds the chair of Commonwealth Professor of English at the University of Virginia.

Her collection of poems, Thomas and Beulah, based on the lives of her grandparents, earned her the 1987 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. She is only the second African American to win this prize.

In 1993, she was appointed to a two-year term as Poet Laureate of the United States and Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. She was the youngest person, and the first African American, to receive this highest official honor in American letters.

When did you first know what you wanted to do?

Rita Dove: It was a gradual thing. I loved to write when I was a child. I thought it was something I would do for fun, and it really wasn’t until I was in college. I wrote, but I always thought it was something that you did as a child, then you put away childish things. Because I never knew any writers, I didn’t know writers could be real live people.

The first instance that maybe it was a possible thing happened in my last year of high school. I had a high school teacher who took me to a book-signing by an author, John Ciardi, and that’s when I saw my first live author. That’s why I know it’s so important to show kids that there are real live people doing these things. I was in 12th grade. I didn’t know his work. Afterwards, of course, I began to read his work.

Here was a living, breathing, walking, joking person who wrote books. And for me, it was that I loved to read, but I always thought that the dream was too far away. The person who had written the book was a god, it wasn’t a person. To have someone actually in the same room with me, talking, and you realize he gets up and walks his dog the same as everybody else, was a way of saying, “It is possible. You can really walk through that door too.” That was the important thing.

When I was in college, I took creative writing courses and I began to write more and more, and I realized I was scheduling my entire life around my writing courses, and I said, “Well, maybe you need to figure out if this is what you want to do.” That was the point.

I’ve read there was a moment when you discovered verse. Can you tell us about that?

Rita Dove: My parents had two half-walls of bookshelves. And they encouraged us to read whatever we wanted.

Going to the library was the one place we got to go without asking really for permission. And what was wonderful about that was the fact that they let us choose what we wanted to read for extra reading material. So it was a feeling of having a book be mine entirely, not because someone assigned it to me, but because I chose to read it. There was an anthology up there. One anthology of poetry. It was a purple with gold cover, I’ll never forget. It’s really thick. It went from Roman times all the way up to the 1950s at that point. And I began to browse. I mean, I really was like browsing. I read in it a little bit. If I liked a poem by one person, I would read the rest of them by that person. I was about 11 or 12 at this point. I had no idea who these people were. I had heard of Shakespeare, sure, but I didn’t know the relative value of Shakespeare, of Emily Dickinson, or all these people that I was reading. So I really began to read what I wanted to read, and without anyone telling me that this was too hard. You know, “You’re only 11, how can you possibly understand Sara Teasdale, or something like that?” And that’s how my love affair, I think, with poetry began. This was entirely my world and I felt as if they were whispering directly to me.

And there was a moment when you read a slightly rude poem by Sylvia Plath?

Rita Dove: Oh, yes. That happened in college and it seems kind of late.

It was a poem by Sylvia Plath called “Daddy.” Which is an amazing poem, a hate poem really, to her father, which ends up saying, “Daddy, Daddy, you bastard, I’m through.” Now, it’s an incredible poem because it’s sort of like a nursery rhyme. It rhymes in that way and yet it has this incredible vehemence. And it was the first time that I realized that you didn’t have to be polite. You know, you’re raised by parents who are always concerned to raise you so you aren’t a little animal, you know, in society. And I think that though they never really said directly there are things that you should or shouldn’t say in writing or in learning — they always encouraged us to go as far as we could — still, I think there was this feeling that you had to be nice. I felt that. And that was an enormous release to be able to say, “Well, it is not only the happy moments are things that should be talked about, but every moment.” All the moments that make up a human being have to be written about, talked about, painted, danced, in order to really talk about life. So it was liberating in that sense.

How would you explain to someone who has never read poetry, what it is that so enthralls you?

Rita Dove: I would try to show them what it is about language and about music that enthralls, because I think those are the two elements of poetry.

Very often, people who are not familiar with poetry, or don’t know much about it, are operating out of fear. At some point in their life, they’ve been given a poem to interpret and told, “That was the wrong answer.” You know. I think we’ve all gone through that. I went through that. And it’s unfortunate that sometimes in schools — this need to have things quantified and graded — we end up doing this kind of multiple choice approach to something that should be as ambiguous and ever-changing as life itself. So I try to ask them, “Have you ever heard a good joke?” If you’ve ever heard someone tell a joke just right, with the right pacing, then you’re already on the way to the poetry. Because it’s really about using words in very precise ways and also using gesture as it goes through language, not the gesture of your hands, but how language creates a mood. And you know, who can resist a good joke? When they get that far, then they can realize that poetry can also be fun.

You’ve had some great excitement in recent years in your career. What are some of the moments that really stand out for you?

Rita Dove: The first moment that really stood out in terms of public excitement and recognition was when I got the Pulitzer. I was 34; I had no idea I was being considered. It was really a moment of moving from a very private sense of life to a public sense, and I didn’t even know the book was being considered. I was very pleased that it was that book, though, that in fact got the Pulitzer — Thomas and Beulah — which was a book about my grandparents; a collection of poems that dealt with their lives: first his side and then her side of the story. And it wasn’t a spectacular book. They didn’t endure a train wreck or anything like that. They were living their lives in this quietly heroic way like many people in this country. And that that book was chosen for the Pulitzer was wonderful for me, I think, personally. Also for my parents it was wonderful.

I remember that feeling.

I got the Pulitzer on my husband’s 40th birthday, and I was planning a surprise party, and I didn’t have classes that day. I told everyone at the university, “Don’t call me, I’m going to surprise him.” And when the phone rang and it was the chair of my department saying, “I know you’re there” — speaking through the answering machine — I was, “Shhhh!” — thinking, “He’s not supposed to disturb me! This is my day!” So when he said, “Rita, this is really important,” and I realized his voice was several octaves higher than usual, that was the moment when I really felt like, sort of like the camera lights came on into my life. It was quite distinct.

The second big surprise was when I was appointed Poet Laureate. Again, it came totally out of the blue because most Poet Laureates had been considerably older than I. It was not something that I even had begun to dream about! I thought, after the Pulitzer, at least nothing will surprise me quite that much again in my life. And another one happened. It was quite amazing.

What does it mean to be Poet Laureate?

Rita Dove: It offers someone as a spokesperson for literature and poetry in this country. It means that one becomes an automatic role model. It means that people write me from all over the country, asking me, and sometimes even telling me, what they think a poet laureate should do. I found that immensely valuable. Instead of trying to come up and pontificate on what literature is, to have people come to me and say, “We have to save the children first. You need to talk with children. You need to talk to teachers and make sure they get poetry in the curriculum early.” And I say, “Yes. As a spokesperson for poetry and literature, this is something that I can do.”

It means having a platform from which to talk about something that’s very near to me, about a very intimate art. It’s the combination of the intimate and the public that I find so exciting about being Poet Laureate.

I imagine that holds quite a bit of responsibility also.

Rita Dove: Yes, it does hold that responsibility, and sometimes the shoulders begin to droop a bit. But…

Every time I receive a letter from someone who simply wants to write, not because they want something, because they simply want to say, “I just want to tell you what poetry means to me,” I realize what hunger there is out there for people to be able to read and to write poetry — to feel a connection with other people on a very intimate, interior level. That buoys me up some. There are obligations, too. Distinct duties of a poet laureate. I plan a reading series at the Library of Congress, and advise the Librarian on literary matters. The rest is pretty much left up to me: how I want to promote poetry, how I want to bring it into the households.