I learned how to order my thoughts, and most important, learned how to develop a plan. I discovered the power of a plan. If you can plan it out, and it seems logical to you, you can do it. And that was the secret to success.

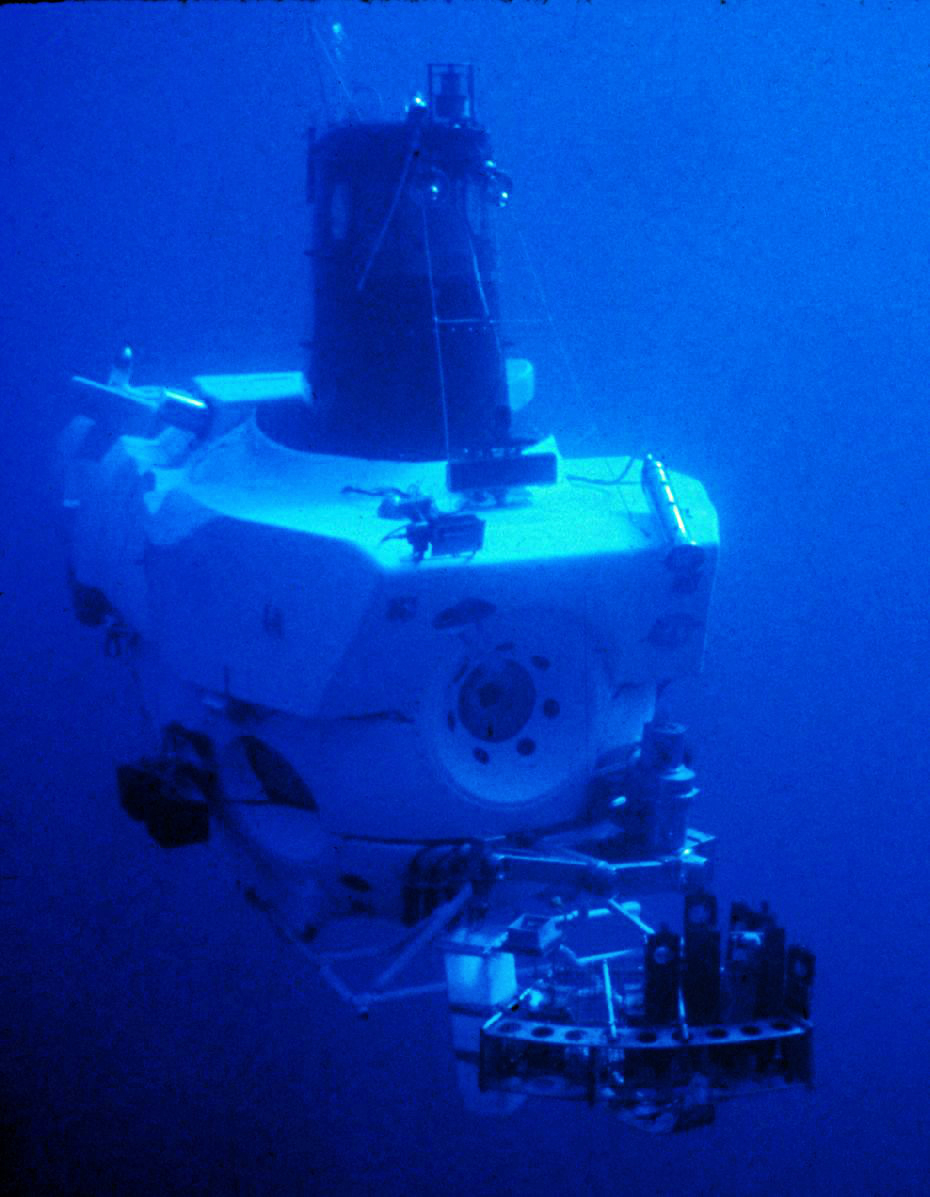

Robert Ballard was born in Kansas but grew up in San Diego, California, where his childhood fascination with tidal pools and marine life ignited his passion for studying marine geology. At the age of 19, in 1962, Ballard secured a job at North American Aviation’s Ocean Systems Group, thanks to his father, a missile scientist at the company. North American Aviation was competing for a contract to build a three-man deep-ocean submersible, which later became known as ALVIN. Ballard would go on to spend a significant portion of his career in this vessel.

During his time at the University of California, Santa Barbara, Ballard earned undergraduate degrees in chemistry and geology. He also participated in the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) and received an army commission. When called to active duty during the Vietnam War, he requested a transfer to the Navy to make better use of his marine geology training. Assigned to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Research Institute in Massachusetts, Ballard continued his work in deep submergence. After leaving the Navy, he returned to Woods Hole as a research fellow and earned a Ph.D. in geology and geophysics in 1974, becoming a full-time marine scientist at Woods Hole.

Ballard’s first major expedition, Project Famous, achieved the first successful field mapping underwater. For over a decade, he dedicated four months a year to conducting extensive underwater explorations, delving into the uncharted mountain ranges of the ocean floor. One notable achievement during this period was the exploration of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and a descent of 20,000 feet in the Cayman Trough.

Through his expeditions, Ballard made a groundbreaking discovery: the entire volume of the Earth’s oceans is recycled through the Earth’s crust over time. This revelation provided the first explanation of the mineral composition of seawater. A pinnacle of this stage in Ballard’s career was the landmark discovery of thermal vents off the Galápagos Islands, where he and his team were astonished to find abundant plant and animal life thriving in the deep-sea warm springs. These plants synthesized food energy chemically, challenging the conventional notion of photosynthesis reliant on sunlight. This discovery has significant implications for the understanding of life on other planets and Earth itself. Ballard was also among the first to witness “black smokers,” submarine volcanoes in the Pacific Rise, emitting heat intense enough to melt lead.

Driven by a desire to expand the possibilities of undersea research beyond ALVIN’s limitations, Ballard developed ANGUS (Acoustically Navigated Geological Underwater Survey), a submersible camera capable of remaining at the ocean floor for extended periods and capturing up to 16,000 photographs during a single descent.

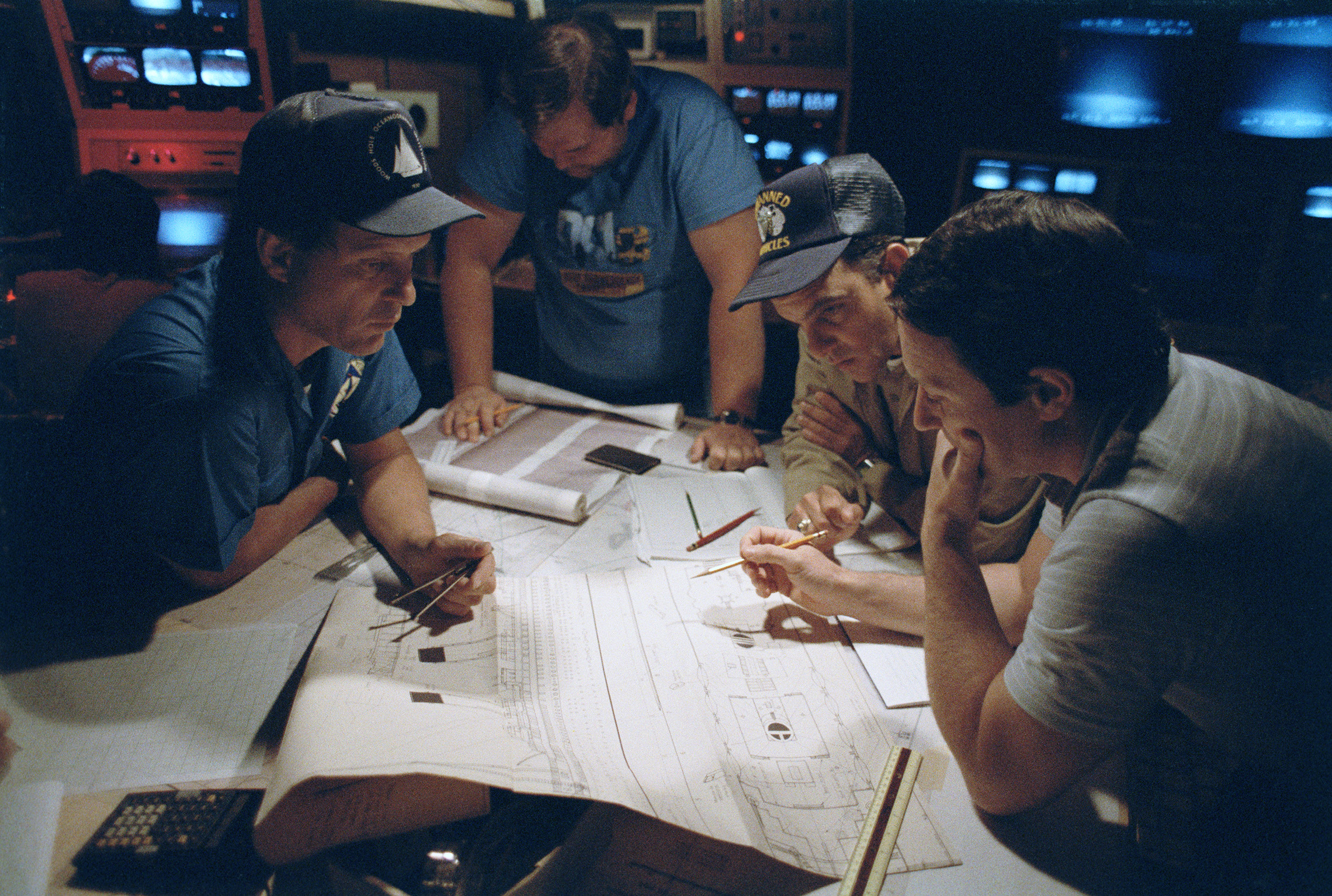

In 1980, Ballard took a sabbatical from Woods Hole to teach at Stanford University, where he conceived an innovative system for undersea exploration—an automated, maneuverable, remote-controlled photographic robot capable of broadcasting live images to a remote monitor. This allowed a large team of scientists to continuously survey and maneuver the remote camera on the ocean floor. To pursue this vision, Ballard sought funding and obtained approval from Navy Secretary John Lehman in 1982.

In 1985, during a joint exploration by Robert Ballard and French oceanographer Jean-Louis Michel, the wreckage of the Titanic was unexpectedly discovered. The dive, however, was initially unrelated to the Titanic and had a different purpose. It was a secret mission to locate the wrecks of two nuclear submarines, the USS Scorpion and the USS Thresher. The true nature of the mission was only revealed by Ballard in 2008 when he disclosed it to National Geographic.

Almost immediately after the Titanic sank in April 1912, there were attempts to recover the wreckage and the bodies of those who perished. However, due to limited diving technology at the time, these attempts remained unrealized for over seven decades. Ballard’s expedition in 1985 was not initially focused on the Titanic. It was only after securing funding from the US Navy in 1982 for a new submersible technology that the possibility of searching for the Titanic arose.

The Navy agreed to fund the project on the condition that Ballard would first search for the sunken submarines and investigate whether the Soviet Union had any involvement. The USS Thresher had sunk in April 1963, followed by the USS Scorpion in May 1968, making them the only nuclear submarines the Navy had lost. Ballard and his team embarked on the mission, and after confirming there were no external weapons involved in the submarines’ sinking, they continued the search.

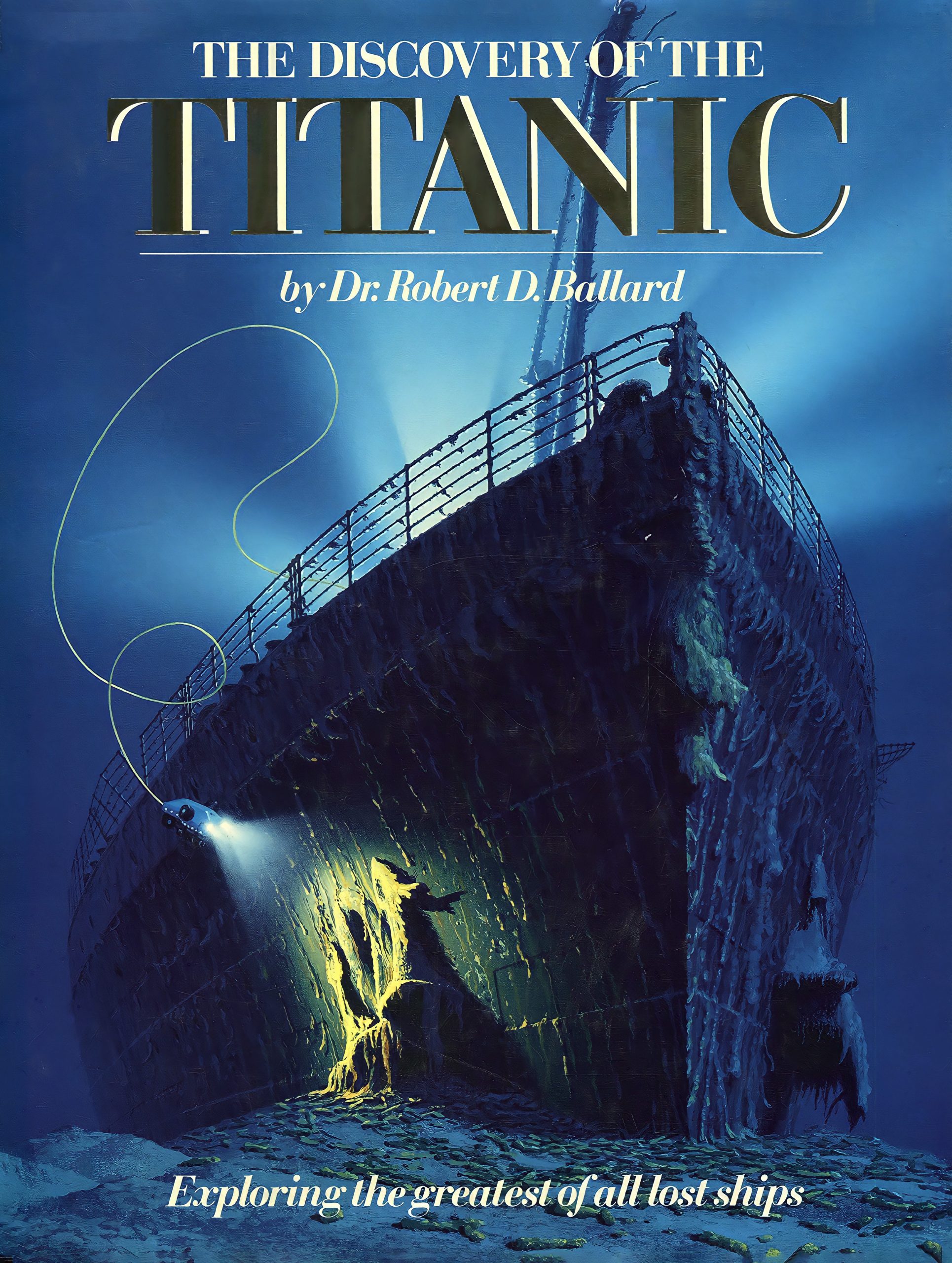

With only 12 days remaining in the mission, Ballard relied on a hunch that the Titanic had split in two and left a trail of debris. This intuition turned out to be correct, leading them to the discovery of the Titanic. However, the Navy had initially been nervous about the publicity surrounding the mission. They never expected Ballard to find the Titanic, and they were concerned about the attention it would attract. Fortunately, people’s focus on the Titanic’s legend prevented them from connecting the dots. Ballard, in his book “The Discovery of the Titanic,” recounted his experience finding the ship and the surreal feeling of being there. The truth about the mission was disclosed 23 years later, shedding light on the events surrounding the Titanic’s discovery and the Navy’s involvement.

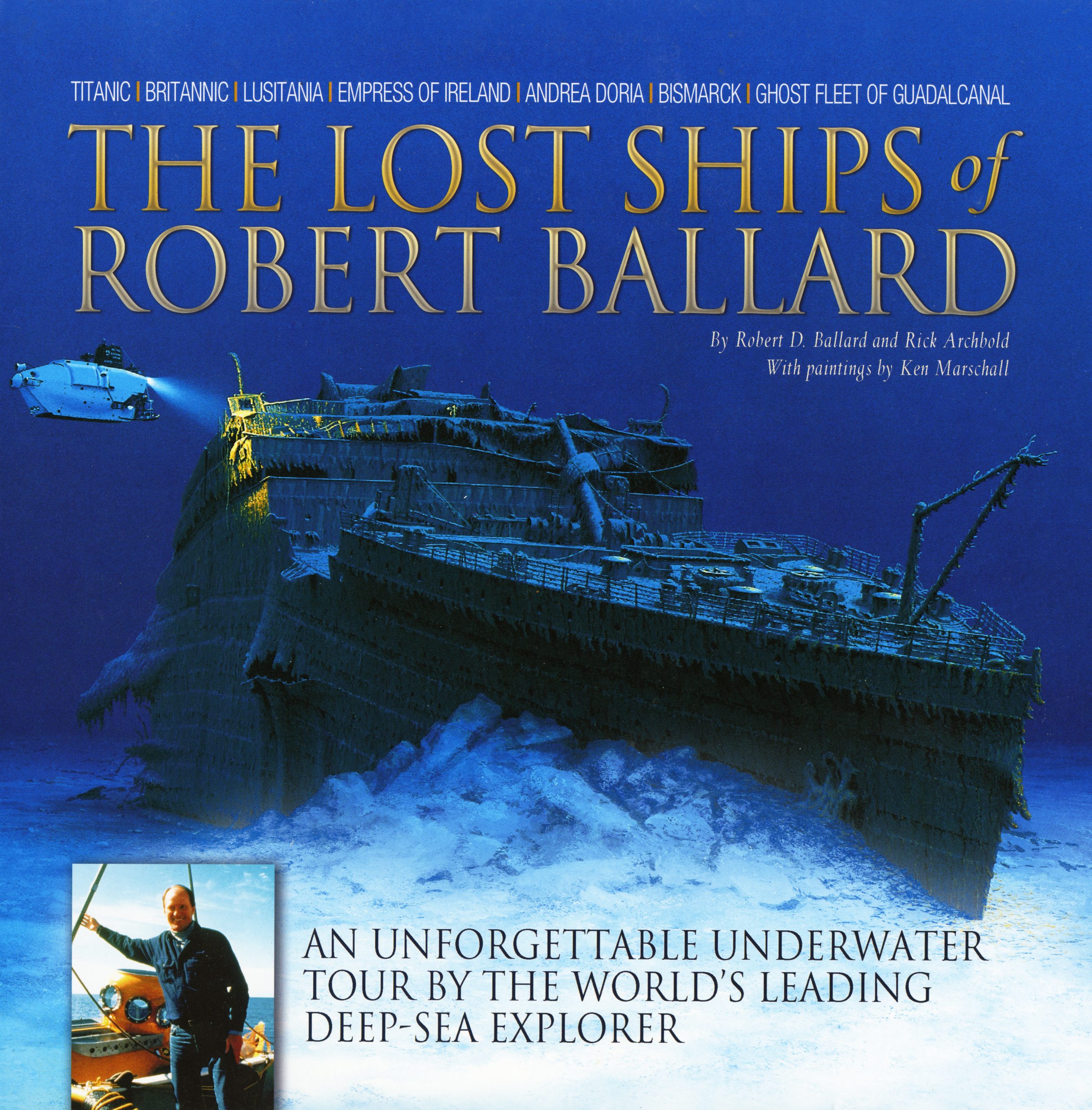

Building on these achievements, Ballard further refined the ARGO/JASON system, using it to locate other historically significant wrecks, including the German battleship Bismarck and the passenger liner Lusitania. In 2002, he discovered the wreck of John F. Kennedy’s PT-109, the craft commanded by the future president during World War II. To date, Ballard has conducted over 120 undersea expeditions, employing the latest submarine technology to explore the enigmatic depths of the ocean.

In 1989, Ballard founded the JASON Project to bring the wonders of the earth, air and sea to classrooms around the world. More than 1.7 million students have participated in JASON programs, learning about natural phenomena — from volcanoes to storm systems — and viewing live transmissions from JASON robots as they explore the undersea world. Dr. Ballard has received numerous awards and honors for his discoveries, including the Lindbergh Award, the Explorers Medal and the Hubbard Medal of the National Geographic Society. In 2003, President George W. Bush presented him with the National Endowment for the Humanities Medal in a ceremony at the White House.

Recent expeditions have focused on the Mediterranean, Aegean, and the Black Sea, where the unique combination of fresh and saltwater has preserved sunken ships for centuries. In the Black Sea, Ballard’s efforts have led to the discovery of ships lost during the Roman Empire, some dating back to the second century AD.

Complete deck structures and cargo, such as amphorae used for transporting oils, wine, or honey, have been found intact. Ballard’s work has also involved exploring the remote Pacific island believed to be the site where Amelia Earhart disappeared in 1937. This expedition, funded by the National Geographic Society, will be recorded for a future television broadcast.

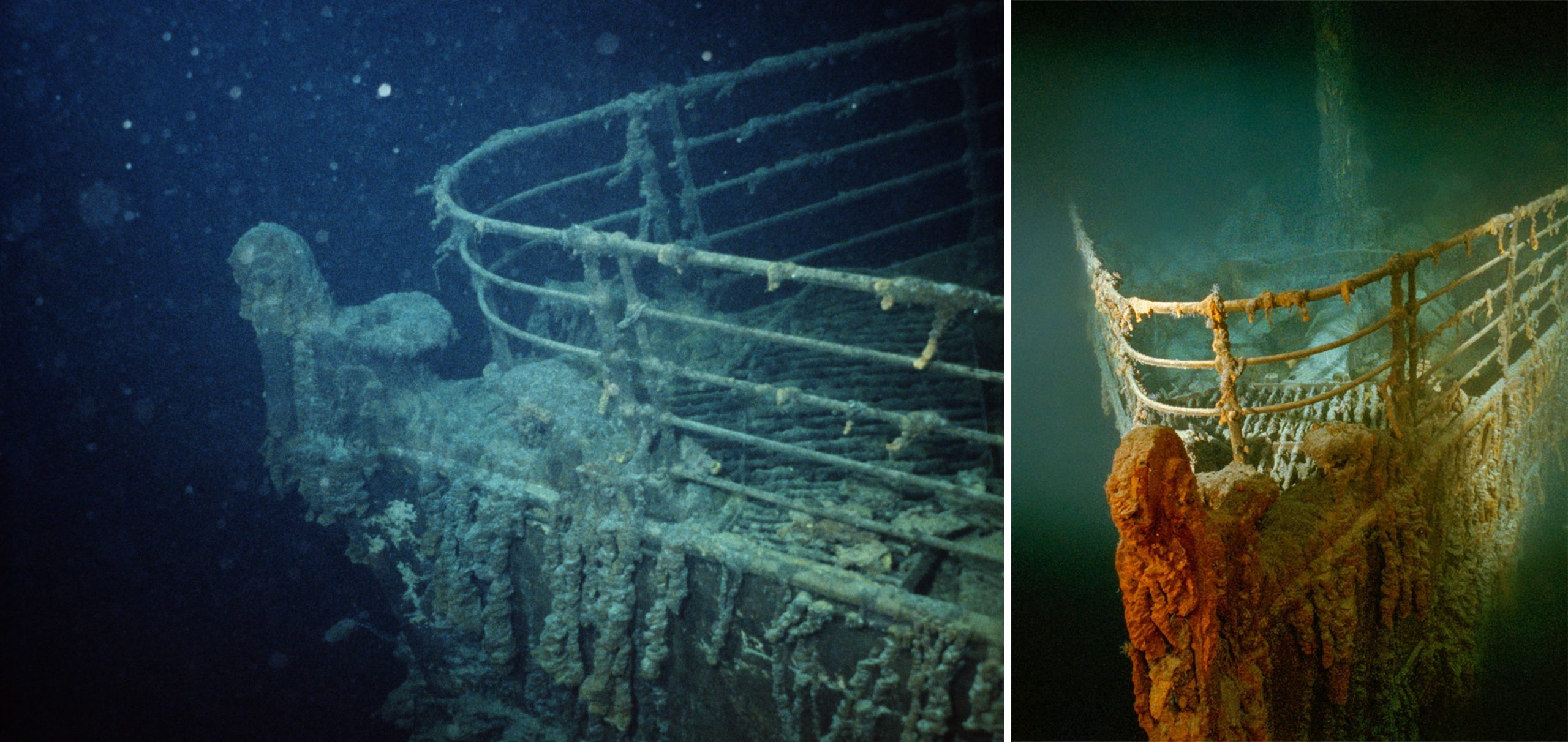

On February 15, 2023, the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution released rare footage of the Titanic’s wreckage to coincide with the 25th anniversary of the movie Titanic’s release in theaters.

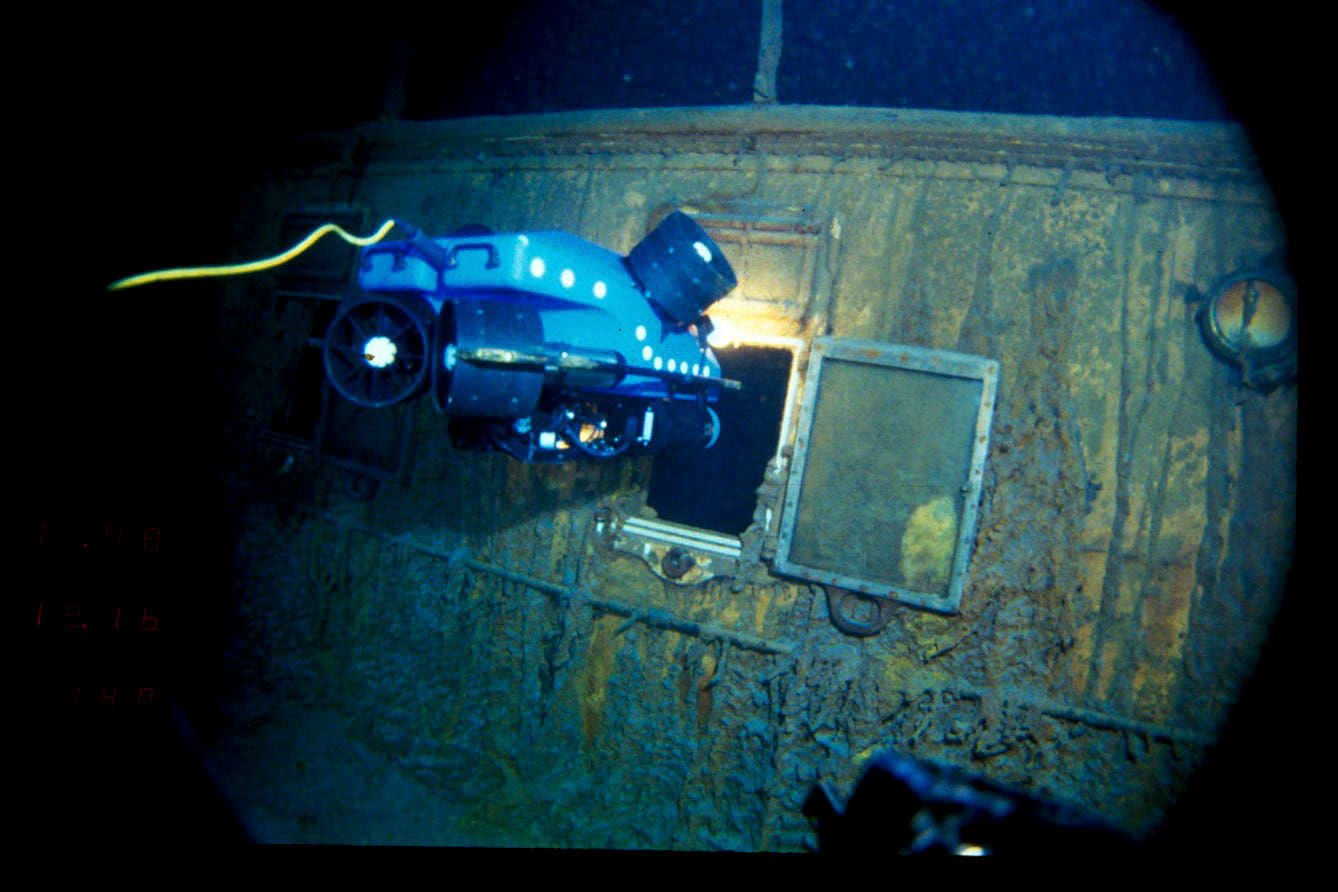

Filmed in July 1986, the footage was captured by WHOI researchers, led by Robert Ballard, aboard the HOV Alvin. Utilizing cutting-edge imaging technology and the remotely operated vehicle Jason Jr., they documented the exterior and interior rooms of the Titanic, which lies over two miles beneath the surface of the North Atlantic.

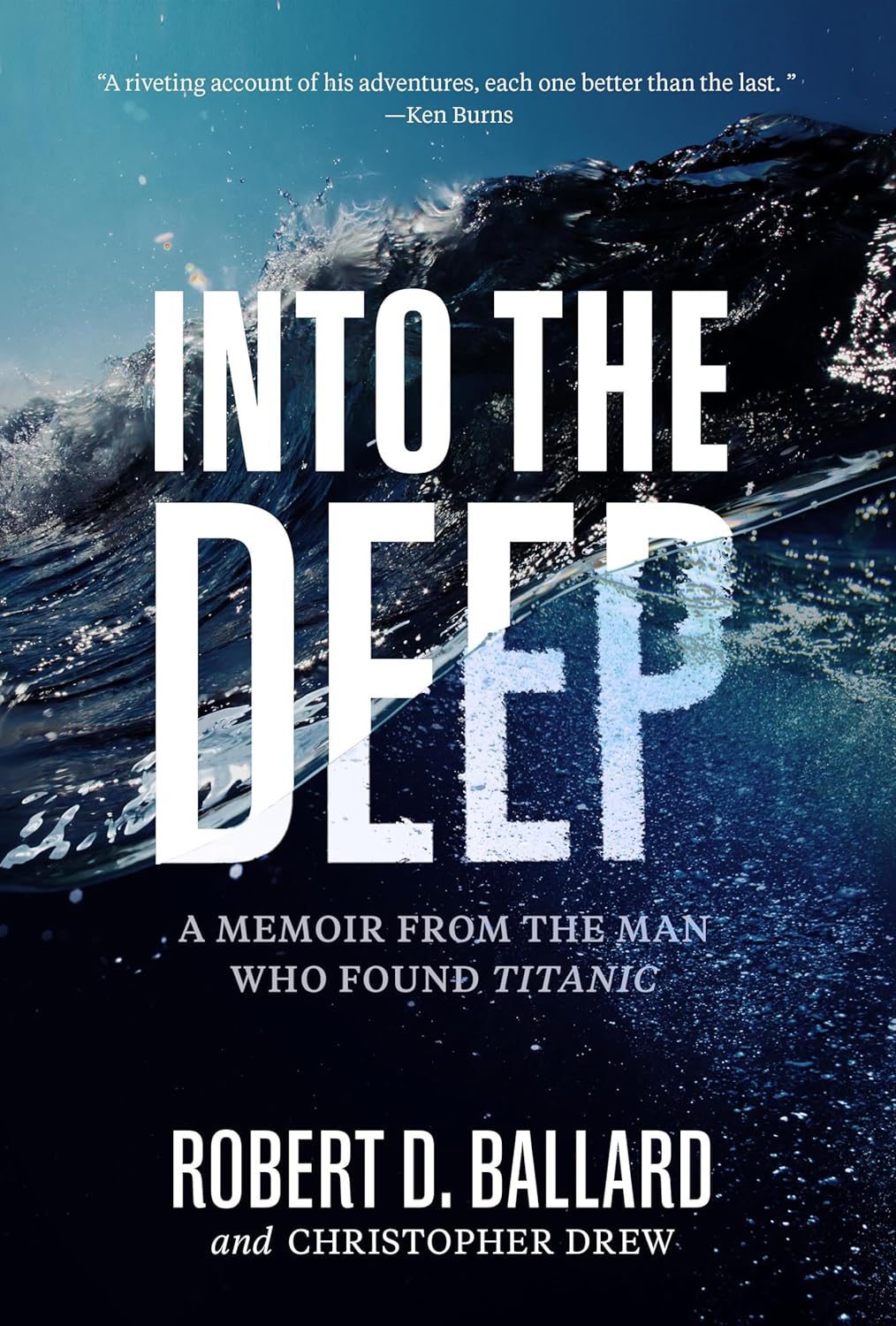

In 2021, Robert Ballard released his memoir, Into the Deep: A Memoir From the Man Who Found Titanic. This book provides an intimate look at the life and career of the renowned oceanographer and explorer. Known globally for his discovery of the Titanic, Ballard recounts his numerous undersea explorations and groundbreaking findings. From uncovering extremophile life-forms at hydrothermal vents to locating historically significant shipwrecks like the Bismarck and PT 109, his career has been marked by significant achievements. Currently, as the captain of the E/V Nautilus, Ballard continues to lead young scientists in mapping the ocean floor, collecting artifacts, and broadcasting live underwater adventures. The memoir also delves into his personal journey, sharing the challenges and triumphs of a dyslexic Midwestern boy who rose to international acclaim as a pioneering ocean explorer.

On January 27, 2024, Secretary of the Navy Carlos Del Toro celebrated the naming of USNS Robert Ballard (T-AGS 67) alongside the ship’s namesake, Robert Ballard, at the National Geographic Society Headquarters in Washington, D.C. Announced in December 2022, the future ship honors Ballard, a retired U.S. Navy Commander and discoverer of the RMS Titanic. The name selection of T-AGS 67 follows the tradition of naming survey ships after explorers, oceanographers, and distinguished marine surveyors. The keel for USNS Robert Ballard was laid in October 2022, with the ship expected to join the fleet in 2026.

Currently, Robert Ballard serves as an Explorer in Residence at the National Geographic Society, President of Ocean Exploration Trust and the Institute for Exploration in Mystic, Connecticut, Scientist Emeritus at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and Director of the Institute for Archaeological Oceanography at the University of Rhode Island.

Premiered on February 15, 2023: This 81-minute, rare, uncut, and unnarrated footage of the wreck of Titanic marks the first time humans set eyes on the ill-fated ship since 1912. Captured in July 1986 from cameras on the human-occupied submersible Alvin and the newly built, remotely operated Jason Junior, most of this footage has never been released to the public. (Credit: Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

“Captain Nemo in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne is who I always wanted to be. Absolutely no doubt about it. I always had this dream of being inside his ship, the Nautilus.”

Like many young readers before him, Robert Ballard dreamed of becoming an undersea explorer after reading of Jules Verne’s 20,0000 Leagues Under the Sea. Unlike most of Verne’s readers, Ballard went on to realize his dream.

For more than ten years, Ballard spent four months of every year at sea, and much of that time miles of feet below the water’s surface, exploring the uncharted mountain ranges of the ocean floor. While his discoveries of undersea volcanoes and chemosynthetic life in the hydrothermal vents off the Galápagos islands have earned him a place in the history of science, his expeditions to discover the wrecks of such famous lost ships as the Titanic, the Lusitania and the Bismarck also earned him a place in the headlines.

His discoveries, and the amazing vehicles he has built to perform his explorations, are even more remarkable than the fanciful adventures of Jules Verne’s Captain Nemo.

In the early 1980s you were already a veteran of many missions in the ALVIN deep-ocean submersible, and had begun developing the ARGO/JASON system you would eventually use to find the wrecks of the Titanic and the Bismarck. How did the Titanic come to be a part of this?

Robert Ballard: I began the development of the ARGO/JASON system, which was a seven-year development, to go from my dream to reality. Along the way I was building systems and testing them. So, from 1982 to 1989, I was developing a new mousetrap. I wasn’t ready to do what I had designed it for: a full-fledged scientific expedition. That takes place this August. August of 1991 is my first chance to do what I dreamed of doing ten years ago. For that ten years, I was building my equipment and testing it. So, the Titanic and the Bismarck were a part of my engineering test program. They weren’t designed to do science; it was designed to prove I could do science. It just turned out to be what most people got interested in. I did not do all this to find the Titanic and the Bismarck. They were a by-product, now very important to the public, but that isn’t what I set out to do. I set out to build this to do exploration. My reason for developing the ARGO/JASON system was to improve my ability to explore the mountains of the sea, which I have been doing all of my life. I wasn’t ready to take that tool down and do that scientific thing. But I could do other things. So I said, well, here we are at Woods Hole, we are building Argo, we’ve got to go and test it, and we will probably go out here in the deepest water that we can get to. Well guess who’s out there? The Titanic is out there. Now if the Titanic had been in the Indian Ocean, I probably would have never found it. But the fact that it was in my backyard, I went, “Let’s go find the Titanic.”

Of course the Titanic couldn’t be more famous, right?

Robert Ballard: I didn’t know that at the time. I knew it was a neat ship, but I didn’t know that it could hit this magic chord. I was completely surprised by the world’s response to our discovery of the Titanic. I thought they would say “Hey, that’s sort of neat. Next.” But I still can’t get away from finding the Titanic. It’s going to track me to the grave.

What was the date when you found it?

Robert Ballard: September 1, 1985.

At some point in this project though, the poetry of the Titanic must have struck you.

Robert Ballard: That came later. When I first set out after the Titanic, it was sort of a mechanical, technical problem. My soul was not in it. My mind was in it. But in the course of getting ready, I had to study it, and I met a man by the name of Bill Tantum, who died just before I found the Titanic. Bill was the soul of the Titanic. He lived in Connecticut, and he started the Titanic Historical Society. He had been injured in Korea, always wanted to be a career Army officer, but he got hurt. His dream went away, and he needed a new dream, and it became the Titanic. This man lived and breathed Captain Smith. When you sat and talked with him, you talked with the past. He knew how many buttons the Captain had on his uniform. He knew everything about it. I was going after him in a very investigative reporter way, but in the course of asking those questions, I had to listen to all this other stuff. It enters your soul, that tragedy. I wasn’t terribly conscious of that, until I found it. Then it blew me right over, like a truck ran over the top of me. It was months before I could deal with it emotionally. It was a complete surprise.

When did you go back to dive on it?

Robert Ballard: After finding the Titanic in September of 1985, I had to wait an entire year before I could go back. The longest year of my life waiting to go back for the weather window to open up. We got back out there. We went out with ALVIN and our little JJ, the vehicle I wanted to send inside to investigate the Titanic. Beautiful weather — gosh, it was gorgeous. It was the summer season, the perfect time to dive. We went out. We had satellite navigation. We knew exactly where the Titanic was. We put in our tracking network, and I got into ALVIN, buttoned up, put it over the side, pulled the valves, to vent it, and down we went. We now began to fall like a big rock for two-and-a-half hours; we’re falling towards the Titanic with all this great anticipation. For the first time seeing it, landing on its deck, tasting it, having it pop into reality from the myth that it was living in, to make it real. Falling through total darkness, and then everything started to go to hell. Everything. We started to have our maiden voyage. The first thing that started to happen was the sonar stopped working, so we couldn’t sweep out and find the ship. Well, that’s okay, because I’ve got my tracking, and I know where I am, and I’ll just drive over there. Then the tracking went out. So now I don’t know where I am. I can’t reach out. All I am is a ball somewhere in the ocean, with a little window. Am I a mile from the Titanic? Is it behind me? Is it in front of me? Is it right or left? Then the submarine starts to take on water into the battery systems, and the alarms start coming on. And, the pilot’s looking at me. We haven’t got sonar, we haven’t got tracking, we are becoming deaf, dumb, and blind down there, and on top of that, the submarine is taking on water, and it’s penetrating into the batteries, and it’s starting to short circuit the batteries. It’s just turning into a disaster, and the pilot says, “Look, we are going to have to abort.” “No! No, no, no. Come on, I’ve waited so long for this moment. Don’t abort the dive.”

He said, “We’re going to watch it, if it gets too much water, I’ve got to get us out of here. If we destroy the batteries, the expedition is over, and you will never see the Titanic.” We went down, and the batteries’ alarms are screaming; he is turning it down so it doesn’t blast in our ears. The bottom comes into view, and it’s just mud. I’m sitting there, and he says, “Well, now what?” All that three-dimensionality in my brain is taking in all this limited data. I’m looking at the currents, I’m looking at everything and my brain just said, “It’s over there.”

We brought the submarine around, and started driving. The alarms are getting worse, and he says, “We’ve got minutes, Bob. We’ve got to get out of here.” “Keep going. Speed up, go faster.” Then I saw a clump of mud, like a mud ball. Like someone had a snow fight. Well, they’re not supposed to be down there. And then there were a few more. I said, “Turn over towards those mud balls.” What it was is the Titanic had hit with such force, it just threw mud balls everywhere, and we were seeing the splatter. I said, “Follow that splatter,” and the mud balls got bigger and bigger and bigger. Finally, out of my window on the starboard side, there is a wall of mud, like a giant bulldozer had just been down there bulldozing the bottom of the ocean. And I said, “Ralph, it’s right around the corner.” We came around the corner and it was in my view port. There was this wall of steel. Like the slab in 2001, like the walls of Troy at night. It was just big, the end of the universe. It just was there as a statement. We came in and I just looked out of my window — I had to look up — because the Titanic shot up a hundred and some feet above me. I’m down at the very keel, and I just went “My God.”

Then we aborted the dive, and we were out of there. I saw it for 12 seconds.

You and your crew were the first people to see the Titanic for how many years after it hit that iceberg?

Robert Ballard: Well, the Titanic hit the iceberg April 14, 1912, at 11:40 p.m. It sank the next morning at 2:20 a.m., April 15. And we were there on September 1, so it was over 73 years since it had vanished.

Did you feel at that point that history kind of struck you in the face?

Robert Ballard: Of course. You know, it’s interesting, when you look back into time. In 1912, the very early moving picture cameras were around, but the world was black and white. When you think of the past, you think of it as if there was no color, and it sort of distances you from that. Black and white always sort of distances you. Even when we first found the Titanic in 1985, our cameras were black and white cameras. So it was still black and white. It wasn’t until I saw it in color that it zoomed from the past to the present, like a lightning bolt, and there it was in today’s reality.

The real thing that got me, when the goose bumps were having goose bumps, was after we fixed the submarine and came down on the second dive. That’s when we made love. Because we came in on the bow and landed, and it was clunk, clunk. It was like Armstrong on the moon. And you took on the ten-degree list of the Titanic. It was listing to the starboard, and you listed. You just sat there. “We… are… on… the… deck of the Titanic. Oh my God!” And you just looked out the windows and just looked at it.

Did the discovery of the Titanic change your life in any way?

Robert Ballard: Dramatically, in good ways and bad ways. Mostly good ways.

I had a chance to warm up to success. I had that ego thing that you go through of being on television and newspapers, and all of that sort of thing when the media has their meal with you. I had done that on a smaller scale. So, when this big thing came, I think I had a proper frame of mind about it. A lot of people who succeed, the ones that do it overnight, it can ruin them. But the ones that work at it for a long, long time, like some stars who get discovered after a 30-year career, they tend to handle it better than the people that are a star in their first movie. I’m thankful that I was prepared, as much as you could be, for something like that. It still was quite an experience, but I think I kept my feet on the ground through it all. You can’t take it too seriously when the spotlight, to some degree arbitrarily, says “Now you are famous.” You say, “Well, I don’t feel any different.” The key is: don’t act any different then.

It’s one thing to climb to the top of the mountain, it’s another thing to stay there. To stay there, you have to be pretty stable about it, and know what you are up against, and use it in a productive way. I think finding the Titanic has helped my career because people believe me when I say I have a new dream. Some people say “Why did you find the Bismarck?” To some degree, to prove it wasn’t luck.

Was it anticlimactic, in a way, going for the Bismarck?

Robert Ballard: The Bismarck was more difficult technically, not anticlimactic. I didn’t expect the Bismarck to be on the Richter scale of the Titanic, but it registered pretty strong. I think the television special we created on the Bismarck — which won an Emmy for the best documentary — was a better film. I think the book we did on the Bismarck was a better book. It was more difficult, but I accept the fact that it isn’t the Titanic.

I don’t want on my gravestone: “Bob Ballard, Discoverer of the Titanic.” I want “Bob Ballard, Explorer.” I’ve got many years to prove that point still left ahead of me. The Titanic is going to help me, but I don’t want to stop right now.