People come up to me and say, ‘We’ve been to your facilities. They are mind-blowing. How do you keep these standards? How do you keep this mindset?’ And the answer is: by phenomenal attention to detail, and by sharing and infecting people with your passion for perfection, your desire for perfection.

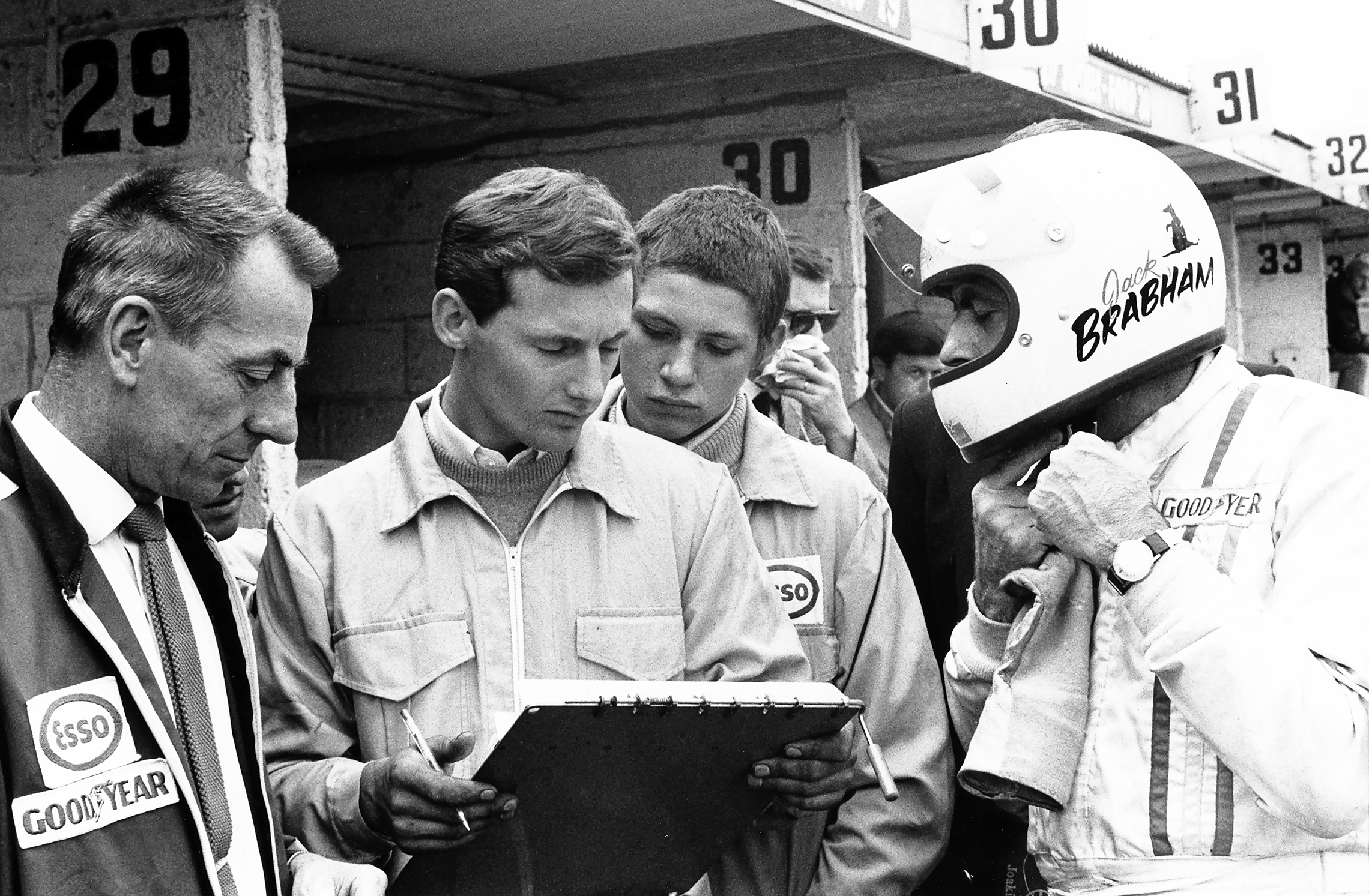

Ron Dennis was born and raised in Woking, Surrey, southwest of London. Race cars and motorsport captured his imagination at an early age. As a teenager, he hung around the facilities of Brabham Racing until he was offered a part-time job, making tea and doing other chores while he learned everything he could about building and preparing race cars. He studied motor engineering at Guildford Technical College, and at age 18 was hired as a full-time mechanic by the Cooper Racing Car Company.

From the beginning, Ron Dennis had his sights set on Formula One, the highest class of single-seat racing. The Formula One circuit consists of a series of Grand Prix races, held in cities around the world, with cars competing on challenging irregular tracks or driving through city streets and country roads. A Formula One team constructs its own vehicles, usually with engines supplied by major manufacturers. Each team typically enters two drivers in a given race. Teams are judged on the number of races won and the number of stages, or “posts,” reached first. At the end of each season, two championship crowns are awarded, one for the season’s best driver, and a constructor’s prize for the team that has built the best vehicle.

Ron Dennis devoted himself to his work. His dedication paid off when he was invited to travel as part of the Cooper team to the Grand Prix in Mexico City. For the 19-year-old mechanic, it was a great adventure, his first experience traveling outside of England. Although the car he was assigned to work on did not win in Mexico City, another of Cooper’s cars won the race and as a team member, Dennis enjoyed his first tastes of Grand Prix victory.

When one of Cooper’s star drivers, Jochen Rindt, moved from Cooper to Brabham, he invited the young mechanic to join him. Typically, the race car companies assigned their mechanics to work on a variety of vehicles in the off-season. Dennis agreed to return to his old employer on condition that he be assigned to work exclusively on Formula One cars.

The new hire quickly drew the attention of the team’s owner and principal driver, Jack Brabham, and in 1968 Dennis became Jack Brabham’s chief mechanic. Brabham entrusted Dennis with more and more responsibility until he was essentially serving in the role of team manager. When Brabham decided to retire, it occurred to Dennis that, at age 24, he had all the experience he needed to run a team of his own. At the time, it was unheard of for a young mechanic to start a racing team, but Dennis found a few willing investors, and in 1971 founded Rondel Racing in his hometown of Woking. To get his company started, Dennis could not focus solely on Formula One. He needed to build the business by working first in the lower tiers of motorsport.

Dennis drove himself relentlessly, working days on end, often without sleep. One night, returning home late, he fell asleep at the wheel and collided with a lamppost. The steering wheel penetrated one lung. His head broke through the windshield and he suffered major lacerations on his face and skull. Fragments of broken glass were lodged in both of his eyes. Surgeons succeeded in saving his sight and restoring his appearance, but a prolonged recuperation forced him to delegate responsibility to other members of his business and master a more sophisticated style of management.

By the mid-’70s, Rondel was enjoying considerable success building Formula Two cars. Dennis was poised to build his first Formula One car in 1974 when a key investor, French energy company Motul, withdrew because of a worldwide energy crisis. Dennis was forced to sell his interest in the company as well as his production facilities. At age 27, he was out of work and forced to start over.

Racing teams typically depend on the sponsorship of highly visible corporations. Dennis received an offer from Philip Morris, maker of Marlboro cigarettes, to build Formula Two cars for a pair of drivers from Ecuador. At first, he was reluctant to return to the lower tier of the sport, but he saw that the tobacco giant’s support would enable him to build a new company and eventually return to Formula One. With Marlboro sponsorship, Dennis built Formula Two and Three cars, winning championships in 1979 and 1980. He was now prepared to return to Formula One.

With his new company, Project Four, he recruited a maverick designer, John Barnard, to build something unprecedented. Dennis and Barnard learned of the work being done with carbon fiber in rocket engines in the United States. Consulting with an American defense contractor, Dennis and Barnard proposed to build a car with a unified chassis and body made of carbon fiber. This light but durable material, they believed, would make for a uniquely fast and dependable vehicle.

Dennis took the project to his patrons at Philip Morris, but the cigarette maker had an exclusive commitment to Team McLaren for their Formula One sponsorship. The McLaren team, once highly successful, was floundering, and Dennis persuaded Philip Morris executives to assist him in acquiring an interest in McLaren himself, so he could produce the car under the existing contract with Philip Morris.

In 1980, Dennis acquired equity in a restructured Team McLaren Limited, and the MP4/1 (Marlboro Project Four 1) became a reality. Within a year, Team McLaren was winning races again with Dennis and Barnard’s MP4/1, and other companies were struggling to develop carbon fiber vehicles of their own. By 1982, Dennis and an associate had bought out the other partners and Ron Dennis assumed full control of McLaren. Two Grand Prix victories in 1982 and another in 1983 signaled to the world that the new Team McLaren was headed for greatness. In 1984, Dennis brought Techniques d’Avant Garde (TAG) Group into the partnership, acquiring the group’s Porsche-built turbocharged engines.

Under Dennis’s leadership, McLaren was now poised to enter a period of dominance in the sport. With the addition of the turbocharged Porsche engines, Dennis’s MP4/2 won 12 out of 16 races in 1984 and won both the Drivers’ and Constructors’ Championships. The drivers Alain Prost and Niki Lauda led the McLaren team, with Lauda winning the Drivers’ Championship in 1984, and Prost taking the crown in both 1985 and 1986. The McLaren vehicles established an unsurpassed reputation for both speed and reliability. Ron Dennis capitalized on the team’s success by diversifying the business. In 1987, he formed McLaren Electronic Systems, now part of McLaren Applied Technologies.

The last years of the decade brought changes at McLaren. Niki Lauda retired, Dennis switched engine suppliers from TAG to Honda, and signed the gifted young Brazilian driver Ayrton Senna. McLaren enjoyed its best season yet in 1988, winning 15 out of 16 races and taking both the Drivers’ and Constructors’ Championships, the latter by an unprecedented margin. In 1989, Dennis co-founded McLaren Automotive to design and manufacture the McLaren F1 ultra-high-performance sports car for the luxury consumer market.

Friction erupted between McLaren’s two star drivers, Prost and Senna, at the San Marino Grand Prix in 1989. Prost left McLaren the following year, although his acrimonious rivalry with Senna continued. Senna won the Drivers’ Championship for McLaren again in 1990 and 1991, but the following years were difficult as McLaren lost its partnership with Honda, and failed to find a suitable replacement supplier in either Ford or Peugeot. McLaren would win no more championships for the next seven years. Ayrton Senna left McLaren for rival Williams Racing in 1994, only to suffer a fatal accident in that year’s San Marino Grand Prix.

By the mid-’90s, a new deal with engine supplier Mercedes returned McLaren cars to the winner’s circle. In 1995, McLaren won the 24-hour race in Le Mans with new driver Mika Häkkinen at the wheel of the F1 GTR, a racing variant on McLaren Automotive’s high-performance sports car that outperformed the purpose-built racing vehicles of rival teams. In the 1990s, Ron Dennis led McLaren to a new era of dominance, winning both Drivers’ and Constructors’ Championships in 1998, and a second trophy for driver Häkkinen in 1999.

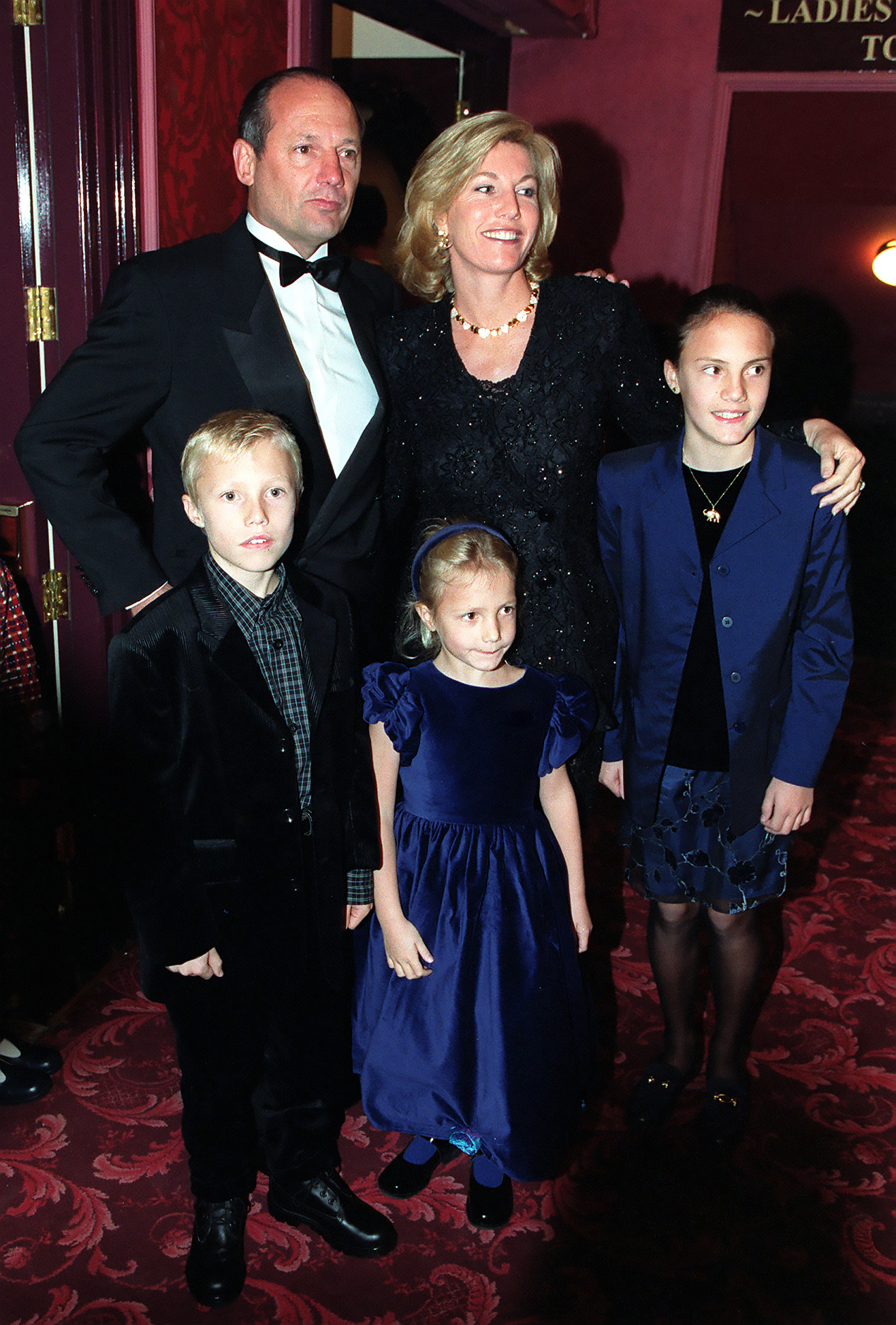

By decade’s end, Ron Dennis had further diversified his business interests, spinning off the in-house catering service to a stand-alone business, Absolute Taste. With a partner from the TAG Group, he acquired luxury watchmaker Heuer, forming TAG Heuer, although Dennis and his partner sold their interest in the business in 1999.

The success Ron Dennis had achieved in business offered him an opportunity to become more involved in philanthropic causes. In 2000, he became a trustee and co-chairman of Tommy’s, a medical research charity investigating the causes of premature birth, stillbirth, and miscarriage. The same year, Queen Elizabeth II named Ron Dennis a Knight Commander of the British Empire for his contributions to British motorsport.

In 2004, Dennis formed McLaren Applied Technologies, absorbing McLaren Electronic Systems and creating a subsidiary within the McLaren Group to further develop the innovations in materials and analytics his workshop had produced, and to find new purposes for them, not only in the automotive industry but in many other areas. McLaren’s expanding operations required a new headquarters, and Ron Dennis resolved to make it an architectural showplace as well. After a false start with the firm of American architect Richard Meier, Ron Dennis hired the firm of Foster and Partners, headed by the distinguished British architect Lord Norman Foster. In 2004, the Queen presided over the official opening of the McLaren Technology Centre, a 500,000-square-meter site in Dennis’s hometown of Woking.

The year 2005 was another strong one for McLaren Racing. Although they won the most Grand Prix races of any team that year, they were narrowly beaten for both Drivers’ and Constructors’ Championships. At the end of the year, Dennis announced a 500-million-pound sponsorship agreement with mobile communications company Vodafone. The following year, however, was a disappointment, with McLaren failing to win a single race.

Dennis continued to develop McLaren’s technology and automotive divisions while expanding his philanthropic activities. In 2007, he founded Dreamchasing, a charitable foundation that provides young people with “funding, guidance, and training to help them fulfill their potential and become inspirational role models for others.” Its ongoing projects include support for Fida International, a humanitarian effort to rehabilitate child soldiers and support war-ravaged communities in eastern and central Africa, and for the Royal National Children’s Foundation, which provides shelter and support for children who have suffered trauma, abuse or neglect.

The 2007 season year saw the McLaren team headed for recovery, although rivalry between new drivers caused friction and bad publicity. The year also saw McLaren fined $100 million by FIA, the sport’s governing body, for alleged complicity in the theft of intellectual property from rival Ferrari. Despite these setbacks, Ron Dennis led his team to yet one more victory, with driver Lewis Hamilton winning the 2008 Drivers’ Championship for the Vodafone McLaren Mercedes team.

In 2009, Dennis stepped aside as team leader while retaining his chairmanship of McLaren Group. He increasingly turned his attention to the production of luxury consumer vehicles, launching the MP4-12C high-performance sports car in 2010. A new manufacturing facility, the McLaren Production Centre, also designed by Foster and Partners, was officially opened by Prime Minister David Cameron in 2011. The Production Centre stands side-by-side with McLaren headquarters in Woking. In 2014, McLaren Automotive launched the 650S in two models, Coupe and Spider, and received rave reviews from the automotive press. Dennis also negotiated a new supply agreement with Honda, reuniting one of the most acclaimed partnerships in motorsport. McLaren Automotive continued to create new luxury vehicles, including the 675LT, 570S, 540C, and P1GTR.

Despite the great success of the McLaren Group as a whole, a leadership struggle developed within the company. In November 2016, Ron Dennis stepped down as CEO of McLaren. He retained a 25-percent interest in the company until the following year when he sold his remaining interest to the two principal shareholders and resigned his position on the board.

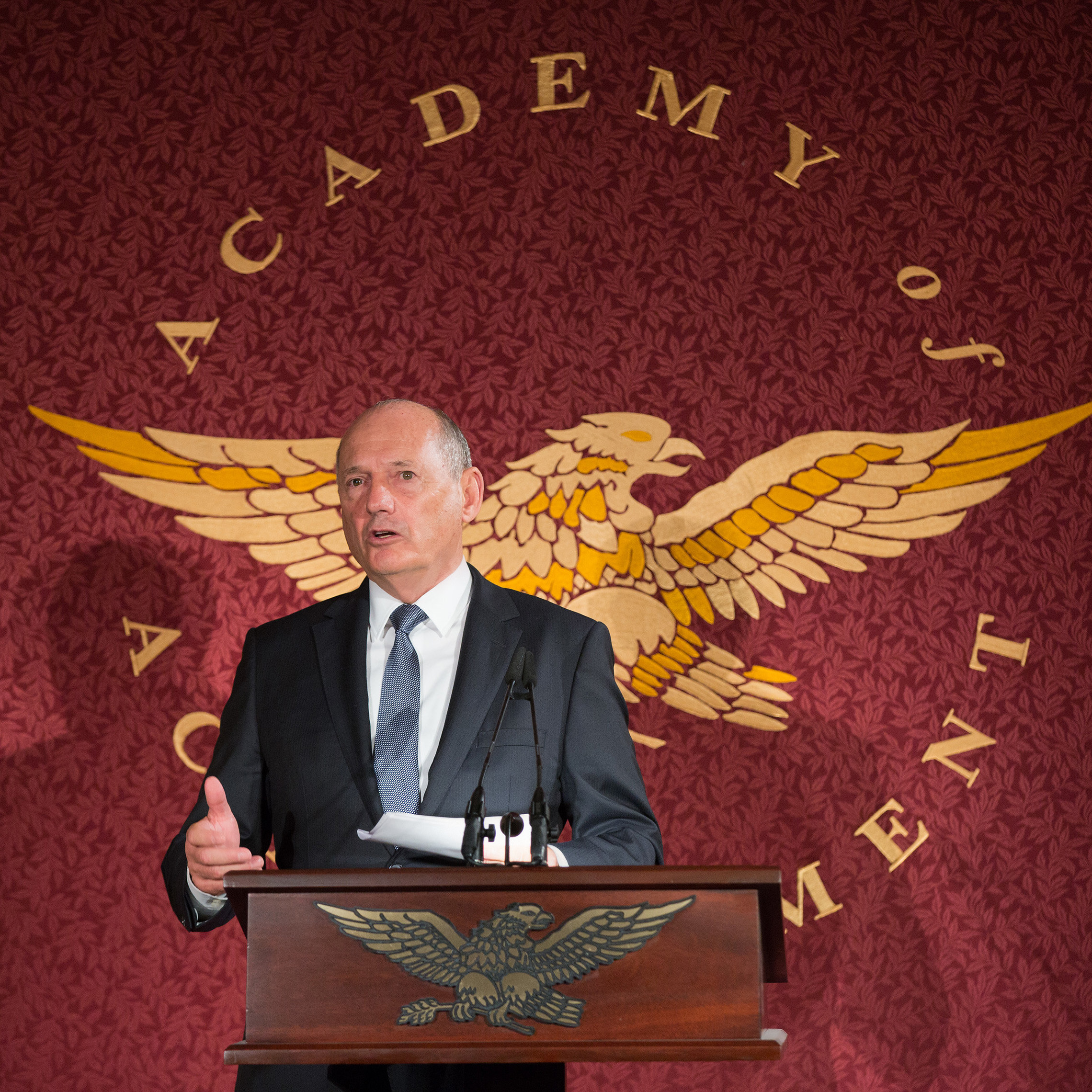

In his 37 years with the firm, Ron Dennis had built McLaren from a losing racing team into a dominant competitor in Formula One, as well as a diversified technology company and a successful commercial automaker. He continues to pursue new business opportunities and charitable activities. His personal achievement as the most successful team leader in the history of Formula One racing remains unparalleled.

The most successful team chief in the history of Formula One racing, Ron Dennis led the McLaren Racing team to victory in 17 world championships and 158 Grand Prix competitions, from the time he first assumed leadership of McLaren in 1980 until his retirement in 2017.

He vastly expanded the enterprise, founding the McLaren Technology Group of companies. Under his leadership, McLaren Automotive produced the most advanced and highly rated sports cars in the world, including the innovative hybrid ultra-high-performance McLaren P1. McLaren Applied Technologies has offered high-tech solutions to clients in the automotive sector and other industries. The company’s technical assistance helped Team Great Britain to win 15 gold medals at the 2012 Olympics, and it has partnered with GlaxoSmithKline to streamline the trial and production process for new medications.

Ron Dennis was named a Commander of the British Empire by HM Queen Elizabeth II for his services to motorsport. His foundation, Dreamchasing, mentors and finances young people around the world to pursue their own dreams.

You were a teenager when you started working at Brabham Racing, running errands and making tea and so forth. By your early 20s you were a top mechanic at Cooper Racing Car Company, and a few years after that, you were starting your own company. How did that come about?

Ron Dennis: One of the Cooper drivers was quite a well-known driver, subsequently one of the few drivers to posthumously win the world championship, a driver called Jochen Rindt. And he moved teams, just as sporting superstars move from one team to another, from Cooper’s to Brabham’s, my old tea-making stomping ground. And he approached me and said, would I go with him? The world championship was very seasonal at that time. Most of the Grand Prix teams supplemented their income by manufacturing cars for the lower categories of racing, and getting out of that manufacturing for other people as part of the company into Formula One was extremely difficult. So knowing that this was the same sort of work practice at Brabham, and effectively most of the Grand Prix mechanics had to go back into the production, I actually stipulated that if I went to Brabham’s, it was on the basis that I wouldn’t go into the production facilities. I would be solely and exclusively focused on Formula One. And to actually give me something to do, they put me on the R&D program and the car development. And I formed a very close relationship then with the part owner and principal driver, which was Jack Brabham. By the time we got to the beginning of the season, he had persuaded me to work on his car as opposed to Rindt’s car, which somehow they smoothed over with Rindt. But that started a long relationship where ultimately I emerged into more of a team manager.

Whilst there are comparable titles in motor racing now, the actual function of the job was completely different. The chief mechanic effectively was responsible for virtually everything, other than the money and handling the drivers. So a team manager would sort of turn up five minutes before practice and leave half an hour after practice. Probably not quite accurate, but basically there was a come-and-go, and the chief mechanic was really responsible for everything, save the money and save the drivers.

So towards the end of the season, Brabham had decided to retire. I didn’t really want to work for any other driver and I had a sense of who was actually going to join the team and drive for the team. And something relatively fortuitous occurred. Brabham was very keen to go back to England immediately after the race and said, “Well, I am going to go straight off to the race. I want you to go to the race official’s office the next day, pick up the check, go to the bank, cash the check, take the money to Mexico City and deposit it in the safe.” And basically, “I’ll see you, X, Y, Zed days in Mexico City.”

Now one of the few perks of that particular era was that the American Grand Prix was followed by the Mexican Grand Prix. And the cars were not flown from Watkins Glen to Mexico City; they were put onto trailers and driven, which took some time. So the moment that the cars had left, everybody jumped on the plane to Mexico City and then bought a small, short ticket to Acapulco. Acapulco was just mind-blowing in those early days. It was sort of a supercharged version of Rio. It was full of fun, full of risqué entertainment — it was just amazing. So I performed all my duties and deposited the briefcase in the safe in Mexico City and off I went to Acapulco.

I was lying by the swimming pool, musing over, “What am I going to do?” etc., etc. So I thought, “You know, I’ve run the team. The drivers came and went. I collected the money. Why don’t I do my own team? Because if you have a good team, the drivers want to drive for you.” Now, how naïve was that? The little thing of capital didn’t exist. So with not so many savings, and with a lot of help from other people, I started my own team in one of the lower categories. Completely unheard of! This became the norm. In a few years after, most small teams were started by young mechanics or engineers that had seen what I could do and how I had basically made what appeared to be impossible possible.

I was in my 20s — mid-20s — and the driver for the following season following Brabham’s retirement was Graham Hill, someone who had won world championships. A little immature, but competent, obviously. And I was building, effectively, the cars for the next season in the production workshop. He came in and said, “What are you doing in here?” I said, “I’m building some Formula Two cars, so I’m not on the Formula One team, I have decided to go on my own.” He said, “Well, nobody told me. I thought you were going to be chief mechanic.” I said, “No, Graham. I am going to start my own team.” There was an initial look of, “It’s not how I expected it to be,” and then he said, “Who is driving them?” I said, “Well, I’ve got two young guys that are paying.” He said, “Would you like me to drive one of the cars?” So I said, “How can I pay you?” He said, “We’ll negotiate the start money together. We’ll play good guy/bad guy. And as and when we get enough money that makes sense for me to race, we’ll go 50-50. “ And off we went. He drove the whole season. And actually, we were second in the first race, and we actually won the second race.

And the standards — not just my standards, but in fact, they were Formula One standards, perhaps enhanced by my own standards — were so much higher than anyone else in that category that the team stood out. A lot of the detail spent the whole winter preparing and didn’t have that success.

And coming from a group of mechanics that had basically formed themselves into a team, it started to really surprise people, and then the momentum started to get into it and I started to grow so fast. At one point I had, I don’t know, one, two, three, four teams in different categories, racing different types of car, different mechanics, going in different directions, growing my workshops and everything.

At some point in the process, I started to count up, you know, what are my assets, started thinking materially, because obviously the opposite of a profit is a loss, and I didn’t want to catch a cold. Then there was an oil crisis, and my principal sponsor was a French oil company that made one of the first synthetic oils, a company called Motul. They just called me up, and they said, “The spot price has just gone through the floor…” blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. So I mean, oh my God! I could just… five minutes of prepping me for the inevitable. “And therefore we have decided to stop, and we won’t be fulfilling our contractual payments because we can’t.” And that pretty much brought me to my knees. It was hard, but I went into family-and-friends mode. Managed to survive the year. So had an elegant end, because my debt was greater than my assets, so I was technically insolvent. But I had completely underestimated the asset of my factory. And lo and behold, who should walk into my life again was Graham Hill, who said, “I have decided to start my own Formula One team, and it’s very late and I need an instant facility. Will you sell me your facilities?” And whatever the number was, it was multiples more than I expected, and I was able to pay off everybody and have a relatively nominal sum of money left. But it was enough that I maintained my dignity and I went home feeling pretty sad for myself.

One particular night, when most of the things had been going wrong, I thought, “This is it.” You know, as a young person, you think you’ve made it. And then, equally fortuitously, someone who had worked for me in a marketing capacity, who had done a presentation with me to Philip Morris —they didn’t buy the presentation, but they actually took my marketing guy and he had risen in stature through Philip Morris. He reached out and said, “I’ve got a bit of a challenge. I think you can help.” So I said, “What is it?” He said, “We have two drivers, and we’re trying to ingratiate ourselves to the country from where they originate.” So this is sounding a little strange, and he said, “Yes, and they’re not bad drivers. They came fourth in Le Mans in a Porsche…” And I thought fourth in Le Mans in a Porsche is like a “so what” sort of thing.

I said, “Where are they from?” He said, “Ecuador.” I thought, here I am — world champions — and then these two individuals come out of the woodwork. And I said, “No, I’m not interested.” He said, “Think about it.” I said, “No, no, no, no. No, I can’t go backwards.” “You’re not going backwards. You do everything and we’ll just pay.” So I said, “No, I’m not going to do it.” “Well, think about it.” So two days went past, he phoned up and he’s like, “Look, Ron. I really have to find a solution.” So I just thought of a number and multiplied it by six, which was just an inconceivable amount of money, and I just sort of said, “Okay, I’ll do it for this.” He didn’t even phone me back; he immediately said yes. Oh, goodness. But of course, it then gave me a significant amount of money to start again. So I said, “One year of pain to put myself in a position to grow a business again.” And really, that’s how it unfolded.

When you developed the first racing car made of carbon fiber, you approached Formula One sponsor Philip Morris with this idea, but they already had a deal with McLaren Automotive. Then you ended up acquiring McLaren. How did that happen?

Ron Dennis: I went to them and I said, “You know, McLaren is not doing very well, and I have this revolutionary car. I am prepared to show it to you, but you have to be — you are in McLaren if I show it to you.” So I had a senior manager called Dave Zelkovitz at the time, and he was a little bit geeky but really into motor racing. When we showed him the car, it was clear that he understood how this car could be revolutionary. So we prepped a presentation to the Philip Morris board and waited a couple of days. “We’re sorry, we can’t go ahead because effectively we just have too much money invested in McLaren as a brand and we have to continue, but we really think your car is amazing.” Okay, how do I go about this? So a couple of days went past and I phoned him and said, “What about if I buy McLaren?” So this is —how would you say? — it was like a local pharmacy thinking about buying Boots Evergreen (Walgreens). Is that what it’s called? No way this is, you know… And they said, “Well, how would you like to go about that?” And I said, “Very easy, but you have to help.” So they said, “How do we help?” I said, “It’s simple. You tell them if they don’t sell me 50 percent of the company, you won’t sponsor them.” And so it was a little bit crude to say that — it was more elegant — but that was the message.

So they thought, “What does this young guy know?” and, “He’s got the car and everything, and we’ll have 50 percent and we’ll be able to maneuver him out of the situation.” But I then came up with another idea, which was, “We really want the most dynamic, forward-thinking racing team and you’ve got all sorts of things that you say have value.“ I thought, “I don’t need any of those things, so why don’t we have a new factory, and I’ll contribute my car and you can only contribute the things that are going to make this team succeed.” So the car — our car — was late, so we said, “Okay, I’ll lease your old cars for two races. How much is this?” That went in the pot. “Then we’ll have all your engines. I’ll buy those, or the new company will buy them,” etc., etc. And I was extremely strong on not wanting anything but the very essence of what we needed to create a new team.

There was even enough time to make new transporters for the cars, etc., etc. And of course, the value of their assets versus my assets was not hugely different, and I just had enough money to cover the difference. And that formed what was then a rebranded company, from McLaren to McLaren International, which had a different shareholder structure. We said we would evaluate where we were after three years and then decide what to do, but it never got that far.

Two years into the program, Teddy Mayer —who was the principal behind the other 50 percent — and I both had “clean desk” policies. We never went home with anything left on the desk. I came in on Monday morning and there’s a single envelope with “Ron” written on it, you know. And when I opened it, he said, “This isn’t working for me. We need to talk.” That was from Teddy Mayer. So I walked into his office and I said, “Teddy, got your note.” I said, “I don’t really have a problem. I think we’re doing great. I’ve attracted some great sponsors on top of Philip Morris.” The company was fiscally very strong, started to get results. But he was concerned that I was taking too much risk all the time. The risk at that moment was me pushing to commission Porsche to make a new turbo engine for us, and he didn’t see how we could afford it. So it’s a moment of entrepreneurial — I would say — brilliance. I said, “Okay.” He said, “What do you mean, ‘Okay’?” I said, “I think one of us has to buy the other out, but you’ve started this process, so you determine the number and I’ll decide whether to buy or sell.” And it put him in such a quandary. You can imagine —if it was too cheap, I would buy; if it was too expensive, I wouldn’t buy.

But he had forgotten one thing, which was my credibility was very high at Philip Morris, and I think I had been the architect of the rebirth of McLaren. And I sat, and I thought, “My goodness, it doesn’t really matter what number he comes up with. I don’t have it.” So as I mentioned earlier, I had brought in some supplementary sponsors. So the overall budget was, let’s say, three-quarters Philip Morris, one-quarter other sponsors that I had brought into the team. So I came up with another entrepreneurial solution.

I went to Philip Morris and I said, “Look, perhaps you are not really surprised to know that we are in a bit of a deadlock in the company, and I don’t really know who you want to run the company in the future, but it’s going to be Teddy or it’s going to be me. If it’s Teddy, I have to sell.” “Oh no, no, no! We definitely want you. You’re the architect of the current situation. We believe in you.” So I said, “Well, I need some help.” So they said, “How can we help?” I said, “Here’s all the contracts. When we started this contractual arrangement, my budget was completely covered by your contract, and I have now developed 25 percent more income. I want you to forward-pay me that 25 percent out of your contract in one lump sum, but I want you to do it…” — this might not be the day — “I want you to do it on the 23rd of June. The 23rd of June, I have to have the money, and I need to know categorically that I’m going to get the money.” And we discussed the mechanism. They came back and they said, “Okay, we’ll do it.” They said, “Are you sure you’re going to have enough money?” I said, “A hundred percent I will be able to continue, but I need this acceleration of payment.”

So then I went to my bank. I can’t remember what the numbers were, but it was a lot of money, and I said, there’s a banker — who was still the traditional type of bank manager — his name was Mr. Hermson. You know, up until that moment, if I’d had a dog, I would have called it Hermson, and I would have kicked it quite frequently because Mr. Hermson was never very user-friendly. I sat in front of him and I said, “Mr. Hermson, I would like to borrow some money.” He said, “How much do you want to borrow?” I said — whatever the number was — “1.5 million pounds.” So he looked pretty emotionless. I said, “But before you answer, I want to borrow it for 24 hours, and I will give you a guarantee that you will be paid 24 hours after.” So I set the whole deal up. And for tax reasons, the deal was executed in Estoril, Portugal. It was complicated because of all the history of companies and this and that and the other. So there was a table for the documents, and all I could see in Teddy’s face was, he wanted to see his name was on the check. And I had already preempted that, so all the documents got signed. Two lawyers sort of met and said, “Okay, all the documents. Okay, payment.” Boom. And then he had a bank check, just a guaranteed check, you know, cashier’s check, as it were. I could see the disappointment in his eyes because maybe he had even thought at that stage — and I knew he thought how I’d raised the money, but I hadn’t raised it at all that way. And that stayed a deep secret with me. I mean this is the first time I’ve ever really spoken about it. This was 1982, 30-odd years ago. Well, it was very different then. But it was, again, everybody really won. He had a payment that was beyond his wildest hopes. I owned, briefly, 100 percent of the company, because I quickly sold some shares to refinance my life. And that was really the biggest breakthrough. In 1982, I emerged in relatively complete control of the company. I had partners, but they were very silent partners.