I really believe that great creative ideas will find their way to the surface.

Ron Howard was born in Duncan, Oklahoma. His parents were both actors. Ron first appeared on stage at 18 months and made his screen debut at age four. He had a memorable role in the film The Music Man, and became familiar to millions of Americans as Opie on The Andy Griffith Show. The popular program ran for years in prime time and is still in continuous syndication around the country.

At the end of his teens, he joined the cast of another long-running sitcom, playing the leading role of Richie Cunningham on Happy Days. At the same time, he played a leading role in the hit film American Graffiti and in John Wayne’s last film, The Shootist. Howard received excellent reviews for these performances, but by then he was determined to become a film director.

The young actor directed several episodes of Happy Days, but could not find a major studio willing to entrust a feature film to a 23-year-old novice, however well-known. At last, Howard struck an unusual deal with independent producer Roger Corman. Corman had taken chances before, on unknown directors like Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese. Howard offered to act in a film for Corman — for almost nothing — in exchange for the opportunity to direct.

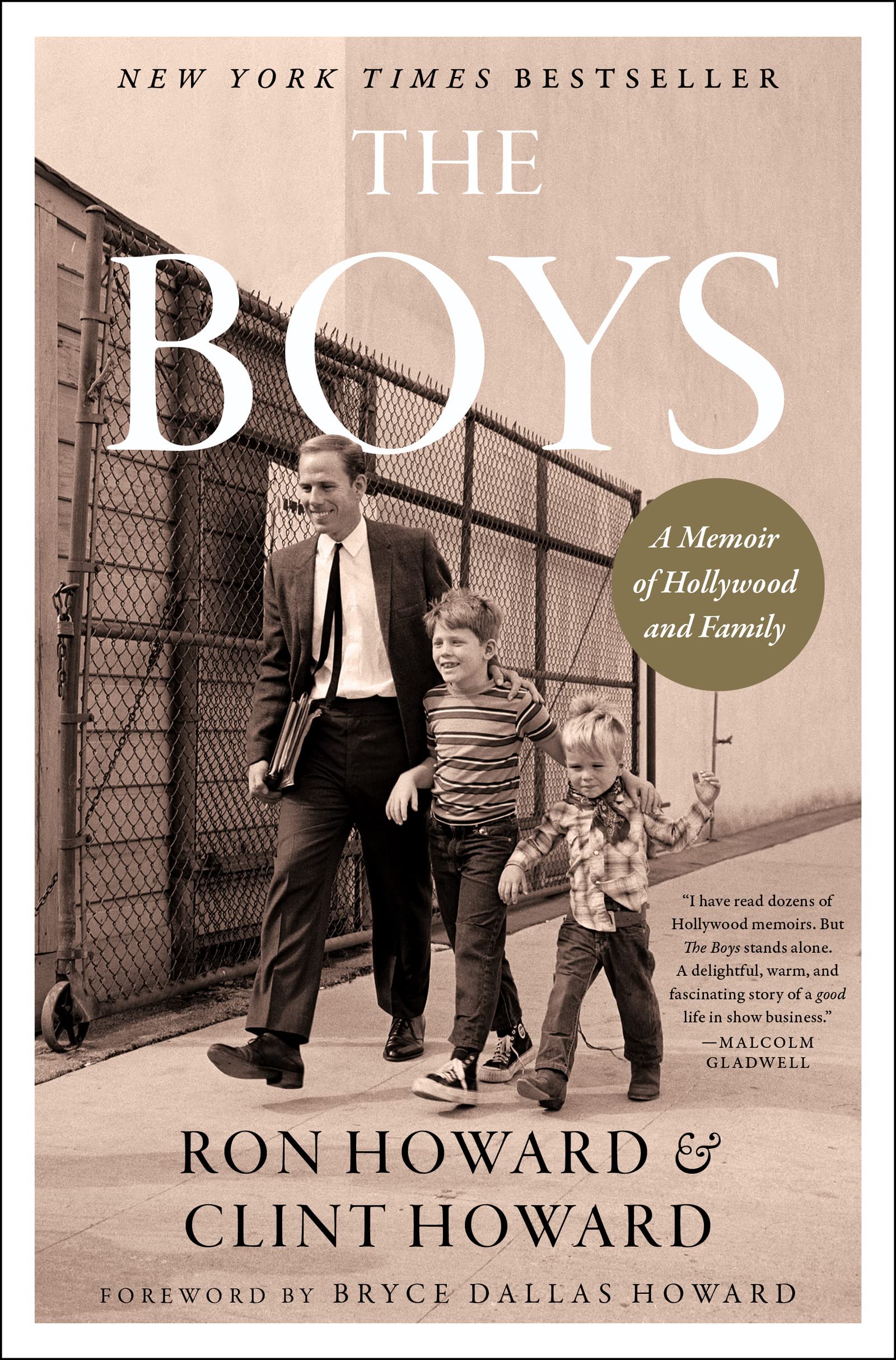

Corman had booked an unmade film into theaters on the strength of its title, Grand Theft Auto, without having a script or even an outline of the film. Ron Howard and his father, actor Rance Howard, cranked out the script in two weeks, and Ron went into production. The surprising success of Grand Theft Auto allowed Howard to break into mainstream filmmaking, starting with the comedy Night Shift, starring his Happy Days co-star Henry Winkler.

In his acting career, Howard had been typecast as the clean-cut all-American boy. Now he found himself pigeonholed as a director of comedies. He first broke out of this mold with the fantasy film Willow, for producer George Lucas. Soon he was combining comedy and fantasy in the enormously popular films Splash and Cocoon. Splash marked the beginning of a long association with actor Tom Hanks. Since 1986, Howard’s films have been produced by Imagine Entertainment, a production company he founded with partner Brian Grazer. In addition to his own directorial efforts, Howard produced the popular films Kindergarten Cop and My Girl.

While continuing his success directing comedies such as Parenthood, and The Paper, Ron Howard moved successfully into large-scale dramas with Backdraft, a suspenseful tale of Chicago firefighters, replete with fiery action sequences. Howard told a tale of real-life heroism in Apollo 13, the story of the aborted 1970 moon mission that nearly cost the lives of its three astronauts. His work on Apollo 13 earned him the 1996 Best Director award of the Directors Guild of America. The one-time child star had moved into the front rank of Hollywood filmmakers.

Howard continued to explore the dramatic side of his craft with the thriller Ransom and an ambitious historical epic, Far and Away, drawing on the experience of his own ancestors as pioneers in Oklahoma. Since its founding, Ron Howard has served as co-chairman of Imagine, which, in addition to feature films directed by Howard and others, has produced a number of highly successful television series, including Felicity, Arrested Development, Friday Night Lights and 24.

As a director, Ron Howard scored one of the major triumphs of his career with A Beautiful Mind, the harrowing true story of John Nash, a mathematical genius stricken with schizophrenia at the height of his career. The tale of Nash’s descent into madness and eventual recovery drew large audiences and critical praise for its stars, Russell Crowe and Jennifer Connelly, as well as its director. The film won four Oscars in 2002, including Best Picture and an Oscar for Ron Howard as Best Director. Howard’s directorial star continued to shine throughout the decade. He struck gold again with big-budget adaptations of the popular Dan Brown novels The Da Vinci Code and Angels and Demons. A more surprising success was Frost/Nixon, the gripping adaptation of a stage play based on former President Richard Nixon’s television encounter with British broadcaster David Frost.

His subsequent films have included a comedy, The Dilemma, the Formula One racing drama Rush, and the 19th-century whaling drama In the Heart of the Sea. In 2016, Howard completed a documentary, The Beatles: Eight Days a Week — The Touring Years, produced in conjunction with the video streaming service Hulu. The following year, he was tapped to direct the next film in the Star Wars series. Howard’s friendship and professional association with Star Wars creator George Lucas dates from their collaboration on Lucas’s breakout hit American Graffiti in 1973.

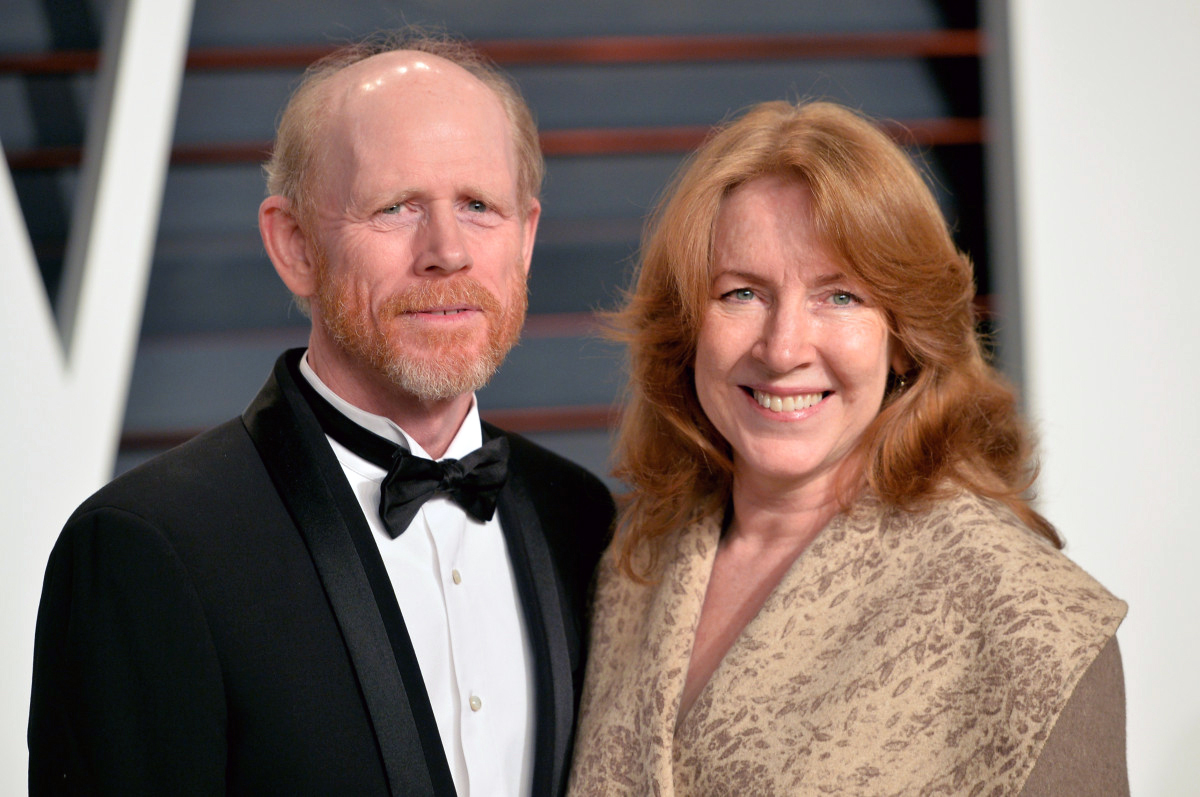

Ron Howard and his wife, Cheryl Alley, make their home in Greenwich, Connecticut. They have four grown children, and a growing number of grandchildren.

“As a young adult trying to make the transition from sitcom actor to motion picture director, I was getting a lot of patronizing pats on the head. ‘Hey, hang in there. In another ten or 15 years, I’m sure somebody will give you a chance to direct.’ That’s not what I wanted to hear at all.”

At age 23, Ron Howard had one of the most recognizable faces in America. His years on The Andy Griffith Show and Happy Days had made him familiar to millions of Americans. He had even directed episodes of Happy Days, but when he looked for feature film directing work, no one believed the young actor had what it took.

Finally he made a deal with low-budget film legend Roger Corman: Howard would act in a film for Corman in exchange for the opportunity to direct. The result, Grand Theft Auto, succeeded beyond anyone’s expectations, and started Howard on his career as a feature film director.

Today, Howard is one of the most sought-after and highly regarded directors in the business. His films, including Splash, Cocoon and Apollo 13, have been some of the most memorable entertainment experiences of our era. He won the 2002 Best Director Oscar for A Beautiful Mind, which also won the 2002 Oscar as Best Picture.

Unlike most people, you grew up in the business that you’ve made your life’s work. I’ve seen you mingling with students, and you seem to really give to them. Do you relate that to your own early experience?

Ron Howard: I was very fortunate because as a child, I was exposed to something, the entertainment business, and taught about it in a really solid way. My dad is a very good natural teacher. He really gave me the fundamentals. A lot of children are put in that situation, and they’re just a little bit more than trained animals. They look cute, and people want to get a certain reaction out of them, so they goad them, or they bribe them, but the children aren’t really learning how to act. So I had that going for me. The environment, particularly on The Andy Griffith Show, was really wonderful and very inclusive. And if there’s any reason that I like reaching out and talking to people about what I do, it’s because that was very much the environment on The Andy Griffith Show. The actors were really allowed to participate, to contribute. And even as a kid — I’m talking about six, seven, eight years old — I was allowed to raise my hand and offer up a point of view about a scene, or changing a line of dialogue, or making something a little bit more natural. I was allowed to participate. And, you know, imagine the sort of self-esteem that goes along with being accepted by a bunch of adults. It was extraordinary.

How did you become interested in directing?

Ron Howard: I became intrigued by what the director did primarily because when I was working on the show — The Andy Griffith Show — the actors, they were a blast. I had so much fun hanging around with them. They were interesting, they were smart, they were funny. They were playing practical jokes, then on a dime, they could focus and do great work. And even as a kid, I was impressed with these people. But I also really enjoyed spending time with the crew. They’d let me sit up there and work the camera or learn a little something about sound, how the microphone worked, and placement, and lighting, and things like that. And I enjoyed that time. And, after a while, I realized that the director was the one person who, moment to moment, day in and day out, really got to play with everybody. And the job just started to look very, very good to me.

The thing that I’ve also understood is because my father is sort of a freelance actor, a character actor, he’s never become a star. He’s never had leverage. He’s never had power in the industry. But he’s always worked, and he’s made his living. But it’s always a struggle. It’s always a struggle. I was always extremely fortunate, but I could see my father struggling in what I view as kind of a noble way, because he’s not really getting all the kudos, and the perks, and all the stuff that a lot of people are attracted to the business for. He just liked being a part of it. He liked being a part of it. And that’s what I began to understand — that I was a part of something. And I started to think about what that thing was. What is that process of staging a television show or movie, and communicating with the audience? And it began to be much more to me than just showing up and fulfilling a function because somebody handed me a script. It became an exploration. It became a chance to really keep challenging myself and keep trying to honor this process, this system.

What are some things you had to persevere through? What types of criticisms or rejection?

Ron Howard: Well, that practically goes with the job description because every project is a potential disaster. Each project requires a huge investment, and people are afraid.

As a young person, a young adult trying to make the transition from sitcom actor to motion picture director, I was getting an awful lot of patronizing kind of pats on the head. And, “Hey, hang in there.” And, you know, “In another ten or 15 years, I’m sure somebody will give you a chance to direct.” And that’s not what I wanted to hear at all. I had a lot of frustration about that, and I earned my way out by making student films myself, by writing, and by getting myself into a position with some leverage by being one of the lead actors on Happy Days. I had something I could sort of trade with. Most people get their first chance to direct by blackmailing their way in. Generally, they have to say, “Well, if you want me to write this script, you have to let me direct it. If I’m going to act in the movie, you’ve got to let me direct it.” Nobody really wants to hand a first-time director the reins.

You began your directing career in comedy — a style that was already associated with you. Nothing at all like Backdraft, Apollo 13, or the films that came later.

Ron Howard: When I began directing I was very young. If there was an area where I had some expertise, it was in light comedy. This is something that I’d been acting in — a tone I’d been involved with — for 20 years already. It was easier for me to convince people that I could actually take the responsibility and do the job of directing a film working in that tone. My first movie was a car chase comedy — young people on the run — called Grand Theft Auto. And made for $602,000, but the film made a terrific profit and it got me started. I wrote it with my father, and I had to star in it in order to get to direct it. But that’s the last time that I acted in anything that I directed. Well, I actually had to do a scene in the next film that I directed, but I didn’t like it and I cut the scene out. And the executives in charge of the project, fortunately, liked the movie well enough that they accepted the fact that I cut myself out of the movie. That was the last time that I acted in anything that I’ve directed. Since then, I’ve graduated to more and more ambitious projects, gained the industry’s trust, gained the trust of creative collaborators: great actors, writers, other producers. Slowly but surely, I’ve tried to broaden the range and scope of what I could do as a director.

How did you become interested in the space program?

Ron Howard: Initially, when the idea for Apollo 13 came to me, I didn’t remember the mission very well. And then, as I looked at the facts, I had a vague recollection of it. I always believed in the space program and the spirit of exploration, but I was not a sort of a space junkie. Initially, I thought, “Wow! This would be a great challenge: to try to recreate for the audience the experience of going into space.” And it’s a very dramatic story, and that would be interesting. But I was looking at it more as a sort of cinematic exercise, you know, a great learning experience. However, as I began to learn more about the mission, I began to see that it was, in fact, even more dramatic than I realized. And, more importantly, as I began to meet the individuals involved — not only the astronauts, but also a number of the mission control people who were involved in the rescue — I began to see that this was really a great story of human triumph. A very emotional story and that you could be very, very truthful. And yet, it was a real opportunity to sort of celebrate what human beings are capable of. So my whole point of view about the movie shifted very early in the process. But it was a dramatic shift.