I have been a bit of a risk-taker all my life.

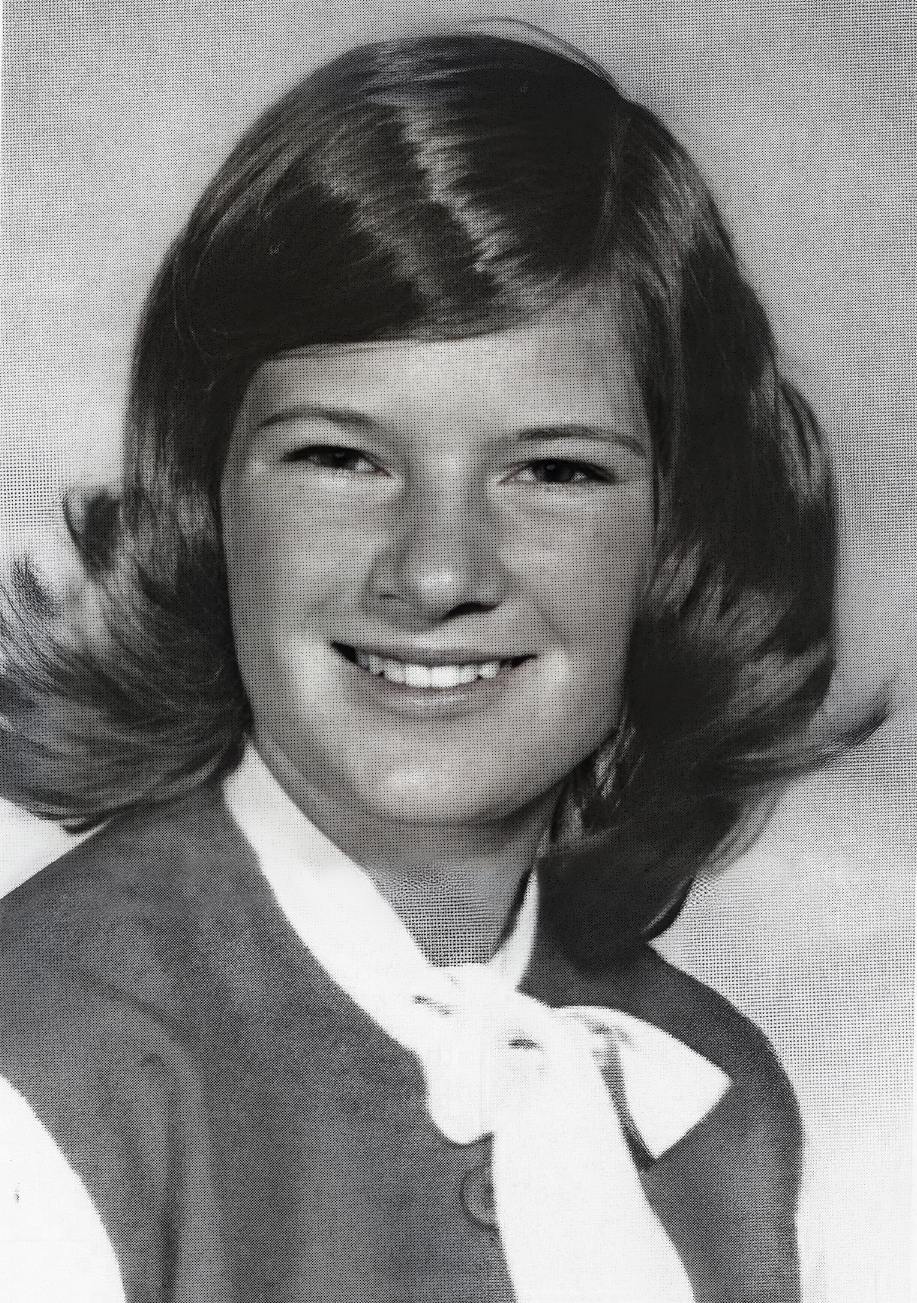

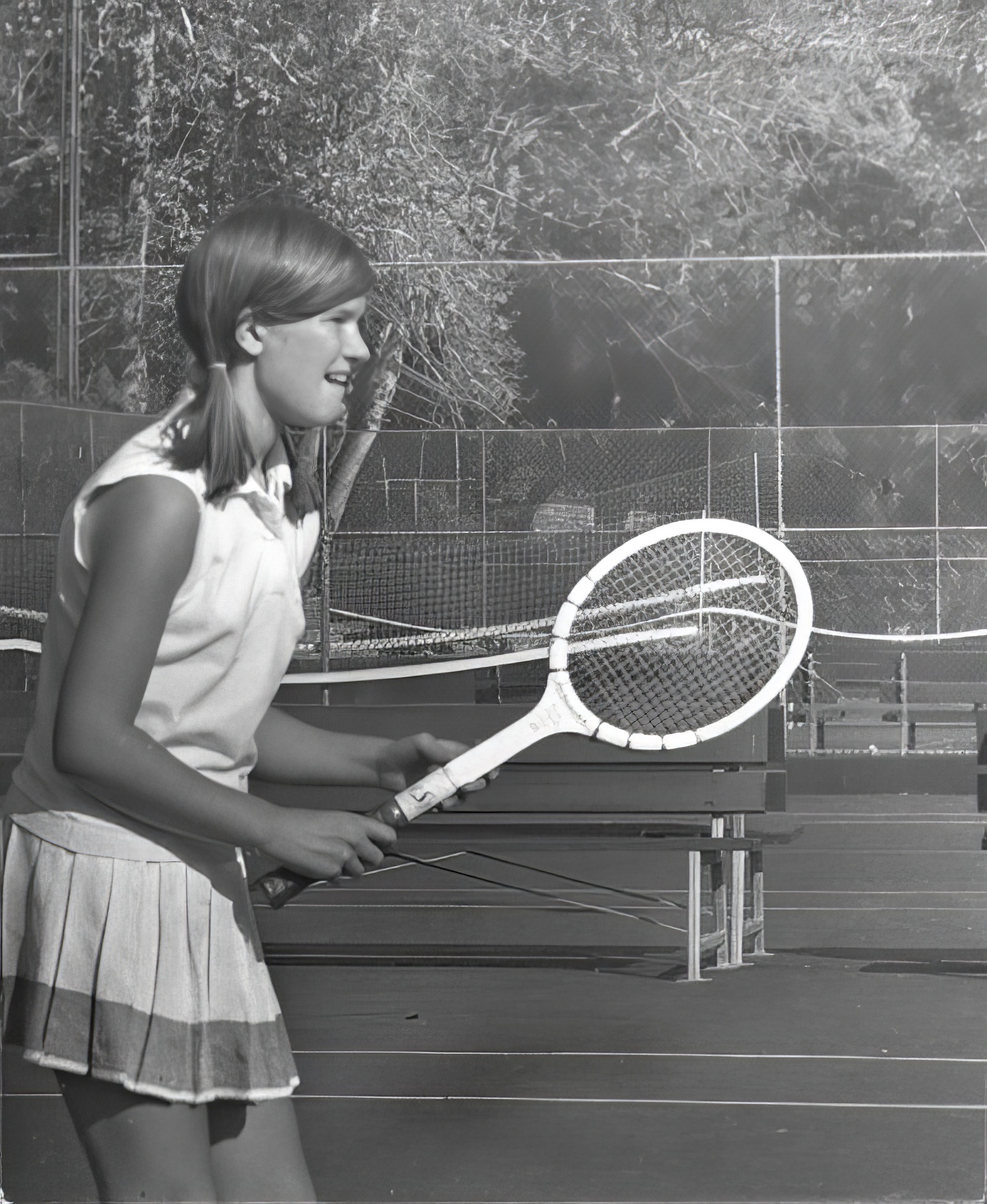

Sally Ride was born in Los Angeles, California, and grew up in the suburban community of Encino in the San Fernando Valley. In addition to being an excellent student with a strong interest in science, she was a talented athlete. At age 10, she began playing tennis, a sport at which she particularly excelled. She became a nationally ranked junior tennis player and attended Westlake School for Girls on a tennis scholarship. After graduation, she enrolled at Swarthmore University in Pennsylvania but soon doubted her choice, wondering if she was missing the opportunity for a professional tennis career. Determined to find out, she left Swarthmore after her first year to see how far her tennis game would take her. After three months of intense training, she concluded that she would not have a professional athletic career and enrolled at Stanford University in Palo Alto, California. She graduated with bachelor’s degrees in both English and physics, and remained at Stanford to earn a master’s and a Ph.D. in physics. As a graduate student, she carried out research in astrophysics and free-electron laser physics.

From childhood, Sally Ride had been fascinated with space exploration, but throughout the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo space flight programs, the ranks of the astronaut corps had been closed to women. From its inception, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) had recruited its astronauts from the ranks of military test pilots.

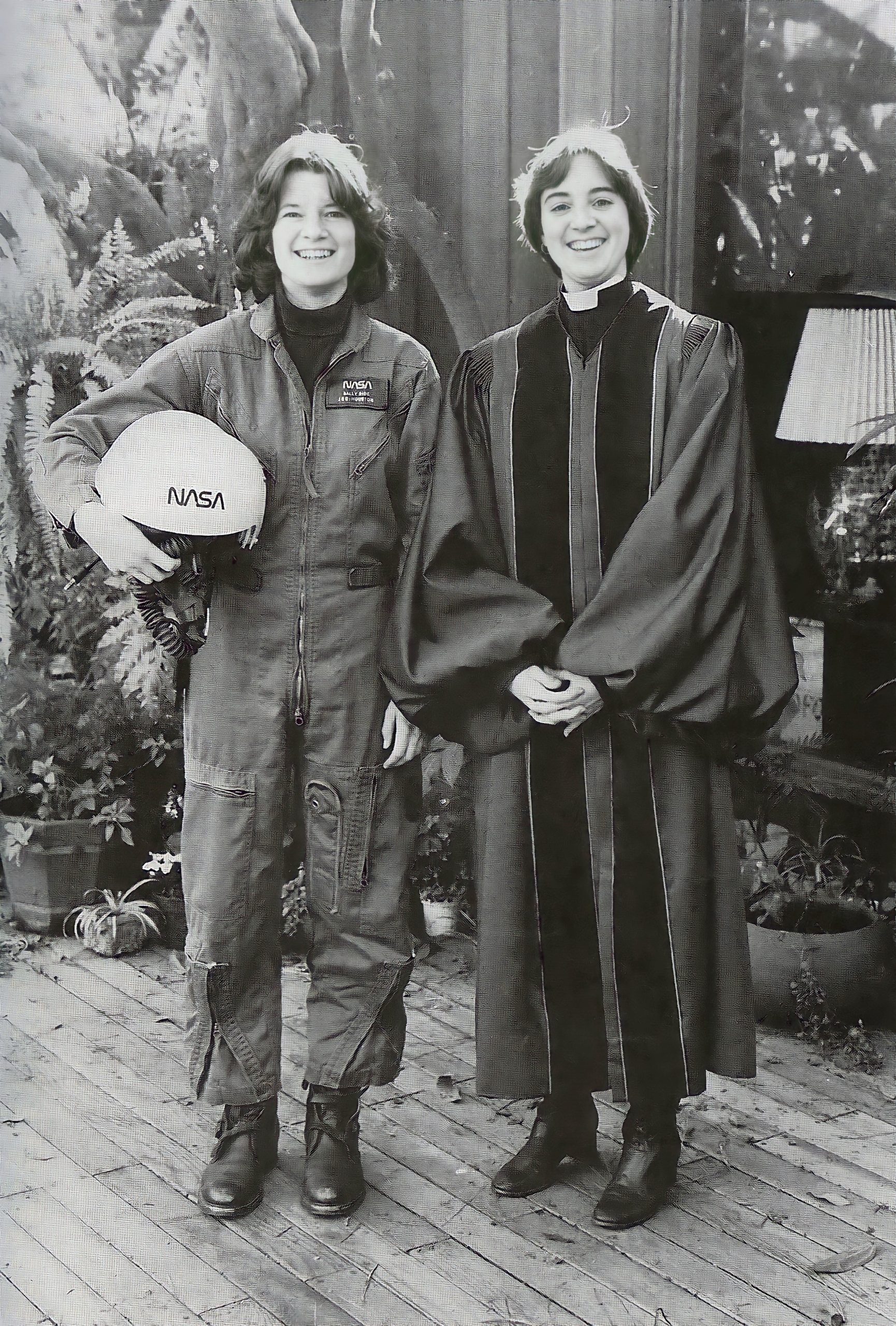

This changed in 1977 when NASA set out to recruit more scientists, including women, for the new Space Shuttle program. At 27, Ride was completing her Ph.D. when she saw an article in the Stanford University student newspaper, saying that NASA was seeking recruits for the astronaut corps. She saw the opportunity of a lifetime. She was one of more than 8,000 applicants for only 35 positions, but to her astonishment, she made the cut, and was one of only six women accepted for astronaut training that began in the summer of 1978.

A year of intensive preparation followed. The new astronaut’s curriculum included classroom studies on engineering, radio communications, navigation, biochemistry, geology, and oceanography. The thirty-five new recruits also learned about spaceflight— from rocket fuels, lift-off, and escape velocity to weightlessness, reentry, and landing. They also trained in parachute jumping, water survival, scuba diving, and the extreme G-forces of launch. Sally Ride came to enjoy flying so much that she earned her private pilot’s license.

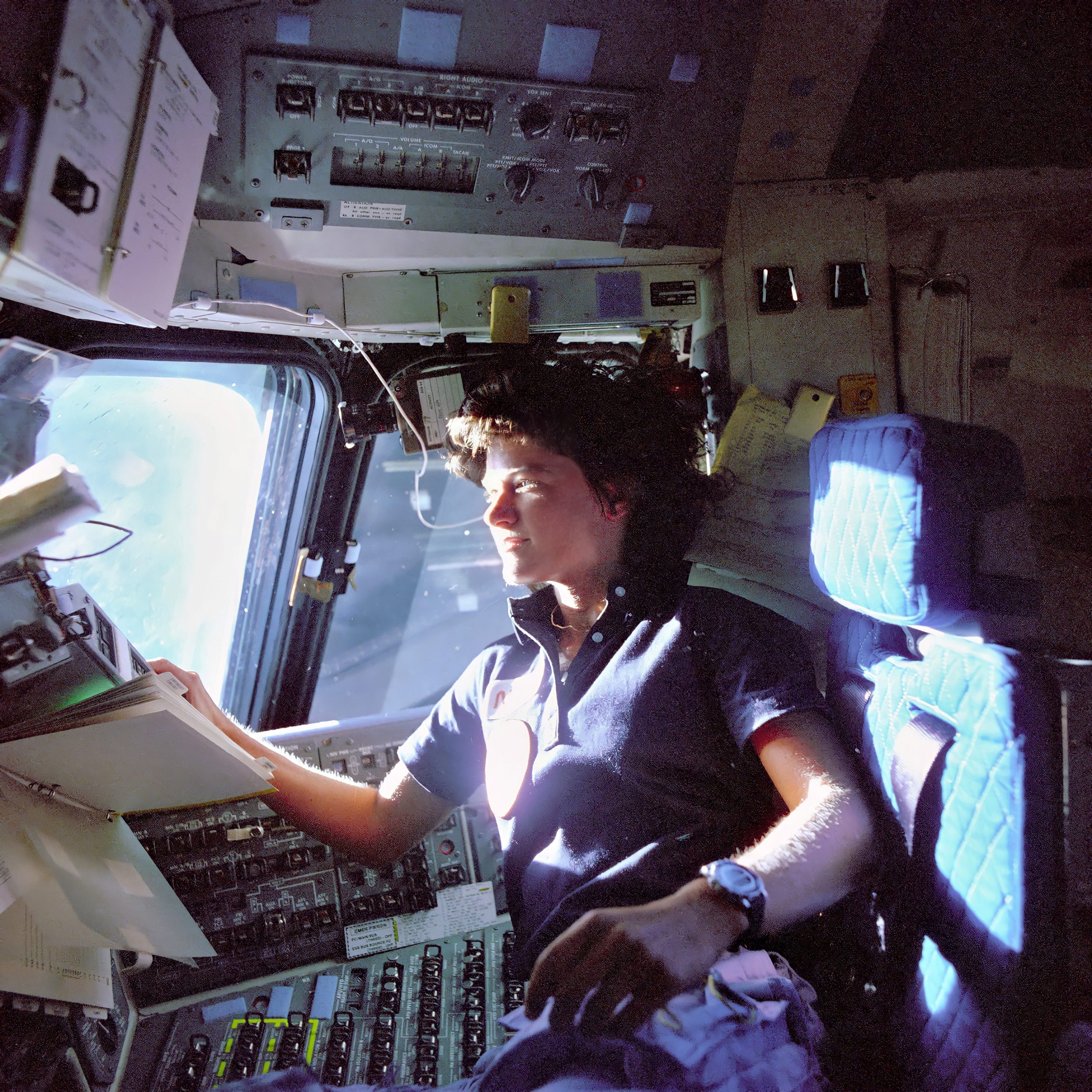

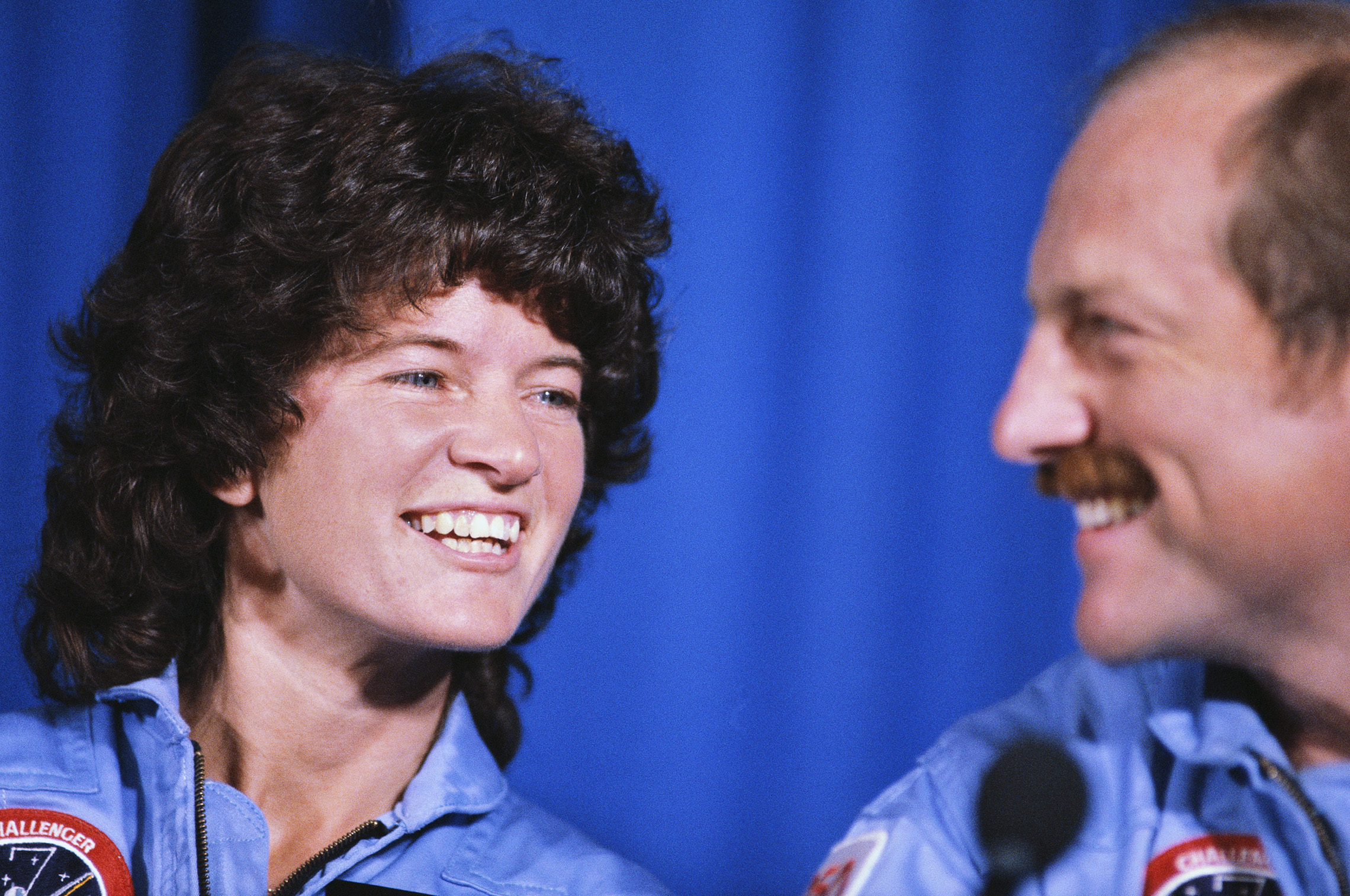

After her initial training period, Ride served as Communications Officer for the second and third Shuttle flights, relaying radio messages from Mission Control to the crew of the Space Shuttle Columbia. She was also assigned to the team that developed the Shuttle’s mechanical robot arm, designed to deploy and retrieve satellites. Two Russian women had previously orbited the earth as part of the Soviet space program, but when Sally Ride was chosen for the crew of the seventh Shuttle mission, STS-7, the story swept through the news media. Sally Ride would be the first American woman to travel in space.

Ride’s mission would be the second flight for the vehicle known as the Challenger, and the first American space mission to carry a crew of five. To the accompaniment of a fanfare of publicity, Sally Ride boarded the Challenger on June 18, 1983, and the Challenger roared from the launch pad and into Earth orbit. Over the course of the six-day mission, the crew used the 50-foot robot arm in space for the first time, retrieving one satellite from orbit and releasing another. In all, the mission deployed two communications satellites for the governments of Canada and Indonesia. It also conducted the first experiment in formation flying with a satellite in orbit, and carried out a number of experiments in material and pharmaceutical research. The mission ended with a successful landing on the lakebed runway at Edwards Air Force Base in California.

Sally Ride returned to space in the Challenger as a mission specialist on Flight STS 41-G on October 5, 1984. This mission’s crew of seven was NASA’s largest yet. The eight-day mission deployed new satellites, made observations of the earth with new large-format cameras and demonstrated a technique of refueling satellites in orbit. The Challenger landed safely at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida on October 13, 1984. Over the course of these two missions, Sally Ride had logged more than 343 hours in space.

Ride was eight months into preparation for her next flight in the Challenger when disaster struck. On January 28, 1986, the Challenger exploded and fell to pieces a few minutes after take-off. The entire crew, many of them her close friends from training days, perished in the catastrophe. Preparation for further missions was immediately suspended.

Ride was appointed to the presidential commission investigating the accident, heading the commission’s subcommittee on operations. When the investigation was complete, Ride was assigned to NASA’s Washington headquarters as Special Assistant to the Administrator for long-range and strategic planning. She led the agency’s first strategic planning effort, and wrote the report “Leadership and America’s Future in Space.” Before leaving NASA in 1987, she founded the agency’s Office of Exploration.

For the first two years after leaving NASA, Ride was a science fellow at Stanford University’s Center for International Security and Arms Control. In 1989 she was appointed professor of physics at the University of California, San Diego, and director of the UC-wide California Space Institute. Under Ride’s leadership, CalSpace, as it is familiarly called, conducted and supported space research with a special emphasis on the application of space technology in the practice of remote sensing and in the study of global climate change. As a research scientist, her work centered on the theory of non-linear beam-wave interactions.

Over the years, Sally Ride became concerned with the under-representation of women in the sciences. Since boys and girls display an equal enthusiasm for science in the early grades, Ride focused her efforts on the promotion of science in the middle grades, when girls in particular often drift away from the study of science. She co-wrote a number of books on space exploration and learning about Earth from space for young readers, including her memoir, To Space and Back, The Third Planet: Exploring the Earth from Space, Exploring Our Solar System, The Mystery of Mars, and Mission Planet Earth and it’s companion book: Mission Save the Planet.

In 1999 and 2000, Ride served as president of Space.com, a website concerning all aspects of the space industry. She then initiated NASA’s Internet-based EarthKAM project, enabling middle school students to shoot and download images of the earth from space.

Tragedy befell the American space program again in 2003, when the Space Shuttle Columbia disintegrated on reentering the atmosphere. Once again, the entire crew was lost, and a government commission was formed to investigate the calamity. Sally Ride was the only member of the previous Challenger Commission to join the Space Shuttle Columbia Accident Investigation Board.

As great as her accomplishments in space exploration and physics, Sally Ride’s most enduring legacy may lie in the cumulative achievement of subsequent generations of girls and boys that she inspired to stick with science, become scientifically literate, and to consider careers in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM).

America’s first woman in space had retired from NASA and was teaching physics at UC San Diego when she decided it was time to use her famous name to advance a cause she cared about. To help narrow the gender gap in science and engineering, Sally Ride would start a science company. In 2001 she joined with her life partner, Dr. Tam O’Shaughnessy, and three colleagues to found Sally Ride Science. Their goal was to promote equity and inclusion for all students, especially girls, in STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) studies and careers. Over the years, Sally Ride Science created acclaimed STEM programs for girls and boys of all backgrounds across the country.

Sally Ride died of pancreatic cancer in 2012 at the age of 61. In 2015, Sally Ride Science found a new home as a nonprofit based at UC San Diego under the direction of UC San Diego Division of Extended Studies. Today, Sally Ride Science at UC San Diego continues Ride’s legacy with innovative programs.

In 2018, the United States Mint announced that Sally Ride’s image would appear on the reverse side of a new quarter, replacing the customary eagle. This Sally Ride 25-cent piece, along with one featuring poet Maya Angelou, is the first in a series of coins that honor the accomplishments of American women.

A life-size statue of Sally Ride was unveiled at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library on July 4, 2023, inspiring the patriotic audience. The statue, made of bronze, stands at the library’s Peace Through Strength pavilion. Sally Ride’s sister, Bear Ride, emphasized Sally’s mission to open young minds and hearts to make the planet a better place. Sally Ride grew up in the Los Angeles area, and her family and friends attended the unveiling. The celebration honored Ride’s groundbreaking contributions to physics and her legacy.

Sally Ride was a 27-year-old Ph.D. candidate, looking for postdoctoral work in astrophysics, when an item in the Stanford University newspaper caught her eye. NASA was looking for astronauts. She was one of only six women to be accepted, out of 8,000 applicants. She joined NASA in 1977, and underwent years of rigorous physical and scientific training. In 1983 she became the first American woman in space, flying a six-day mission on the Space Shuttle Challenger.

Her second mission lasted eight days, contributing to her career total of 343 hours in space. She was scheduled for a third mission at the time of the Challenger explosion in 1986. She served on the presidential commission investigating the accident, and participated in long-term planning at the space agency’s headquarters in Washington until her retirement from NASA.

From 1989, she was a professor of physics at the University of California, San Diego, where her research interests centered on the theory of non-linear beam-wave interactions. She also served as a science fellow of the Center for International Security and Arms Control at Stanford University and as director of the California Space Institute. A passionate advocate for science education, she created the Sally Ride Club and Sally Ride Science Camps to encourage young girls interested in mathematics, science and technology. She was inducted into the Astronaut Hall of Fame in 2003, exactly 20 years after her historic flight.

Was there a moment, an epiphany, a flash of lightning, when you decided what you wanted to do with your life?

I was literally just a couple of months away from getting my Ph.D. in physics when I saw, believe it or not, an ad in the Stanford student newspaper, that had been put in the newspaper by NASA, saying that they were accepting applications for astronauts, and the moment I saw that, I knew that that’s what I wanted to do. Not that I wanted to leave physics, I loved it, but I wanted to apply to the astronaut corps and see whether NASA would take me, and see whether I could have the opportunity to go on that adventure.

Had they ever taken a woman?

Sally Ride: They had never taken a woman. One of the reasons that they were putting ads in student newspapers was that, first of all, they hadn’t taken any astronauts in about 10 years, so they needed to get the word out. More importantly, it was the first time they were planning to bring women into the astronaut corps, and they knew that unless they put announcements in places that qualified women would see them, they would get just the usual suspects of white male military test pilots applying to the program. So this was the first time that they were bringing in women.

Had you ever flown anything before?

I had never flown anything, not a thing. I had flown in very large airplanes, but I had never flown anything. But NASA was looking for — you know, the astronaut corps at that time was still primarily test pilots, but they had some scientists in the corps, and they had made it clear that with the Space Shuttle program, they actually needed an astronaut corps that was more than 50 percent scientists and engineers, less than 50 percent test pilots, so they made it very, very clear that they wanted people with science and engineering backgrounds, and that the test pilot or even a pilot background was not required, they’d teach us everything we needed to know about that.

What were the odds of your being selected for that program?

Sally Ride: They were pretty darned small. There were about 8,000 of us who applied, and out of that, NASA picked 35 of us to be the first Space Shuttle astronaut class.

And you were the young woman who did not want to be called on in class?

Sally Ride: Exactly! Yes! And who has since had to learn how to do television interviews.

Were you surprised to be chosen?

I was surprised to be chosen. I was fairly certain that I would make it a reasonably long way in the selection process, because I was pretty well qualified to apply. I was going to have a Ph.D. by the time the selection process was over, and I had a good athletic background, which NASA — they don’t necessarily look for an athletic background, but they look for a variety of different backgrounds that show that you have got a variety of interests and particularly showed that you can collaborate well with people, work as part of a team, communicate with people. So I knew that I had a reasonable chance to go a reasonable distance in the selection process, but I didn’t think for a minute that I was going to be selected.

Was it tougher for a woman in that first class that accepted women?

It was tougher for a woman, but the reason was really the surrounding culture at the time, the culture at NASA, at the Johnson Space Center, and also the culture in the country. It wasn’t more difficult, interestingly, within the astronaut office itself, the women and men. First of all, the group of 35 of us who were selected included six women, so not just one but six, a little bit of security in numbers, and the 29 men who were selected as part of that group were actually accustomed to working with women. One had had a Ph.D. thesis advisor who was a female physics professor, so they were not unaccustomed to the concept. So we had a peer group that was very supportive and didn’t think that it was that unusual. However, our whole group was set into this culture where it was very unusual. Out of roughly 4,000 technical employees at the Johnson Space Center — 4,000 or so scientists and engineers — I think there were only four women, so that gives you a sense of how male the culture was. When we arrived, we more than doubled the number of women with Ph.D.s at the center.

What did your family and friends think when you applied to the astronaut program?

Sally Ride: They were very, very supportive. I had a lot of friends who also applied to the astronaut program, so they understood completely why I wanted to do it. My parents at least gave the impression that they were very supportive and very excited, and I am positive my father was. I am less positive about my mother, but I think both of them were very excited and very supportive.

Why exactly did you want to do this?

Sally Ride: It’s something that was just deep inside me. There is really no other way to describe it. The moment I saw the opportunity, I knew that that is what I wanted to do. I can’t explain why I wanted to do it, it’s just something that was part of me.

Can you trace it back to those black and white pictures on television?

Sally Ride: Probably so. I was fascinated by those. I remember where I was watching Neil Armstrong set foot on the moon, as all of us who were alive and watching television in those days do, but I was really taken by those pictures.

How hard was it to become an astronaut?

It was hard to become an astronaut. It was hard to make it through the selection process and the training itself was very difficult, not anywhere near as much physical training as people imagine, but a lot of mental training, a lot of learning. You have to learn everything there is to know about the Space Shuttle and everything you are going to be doing, and everything you need to know if something goes wrong, and then once you have learned it all, you have to practice, practice, practice, practice, practice, practice, practice until everything is second nature, so it’s a very, very difficult training, and it takes years.

Did you ever have self-doubts, or fear of failure that you weren’t going to be able to do this?

Sally Ride: Actually, I didn’t. I am not quite sure what that says, but I didn’t.

I didn’t have any doubts that that was what I wanted to be doing, and I didn’t have any doubts that I would be able to do it. Up until that point, up until I joined the astronaut corps, you could say I was a professional student. I had made it through high school, undergraduate, graduate school, to a Ph.D., so I knew how to learn things. I knew how to study, I knew how to concentrate and to dedicate myself to learning one particular area, and that’s what I was doing again, so I was fairly confident and comfortable actually in the environment.

Did you think of yourself as a trailblazer or as a pioneer, not just in space, but for women in space?

Sally Ride: You know, I didn’t.

We all knew that the six of us were the first six women to enter the astronaut corps; we were very well aware of that. We realized that this was a significant breakthrough and that to some extent, we were pioneers and trailblazers, but I have to say that I don’t think I appreciated how much of a trailblazer I was for women and how much women would look up to me as a role model and the things that I had done until after my first flight, after I landed, partly because while I was in training, I was pretty well insulated by NASA. They wanted me in training. They wanted me to learn what I was supposed to learn. They didn’t want me out talking to reporters and the press and the public. So I was not unaware. I read newspapers, I watched television, but I wasn’t face to face with women until I came back from my flight, and then it hit home pretty hard how important it was to an awful lot of women in the country.