If you want to serve the future, don't be afraid to belong to a minority.

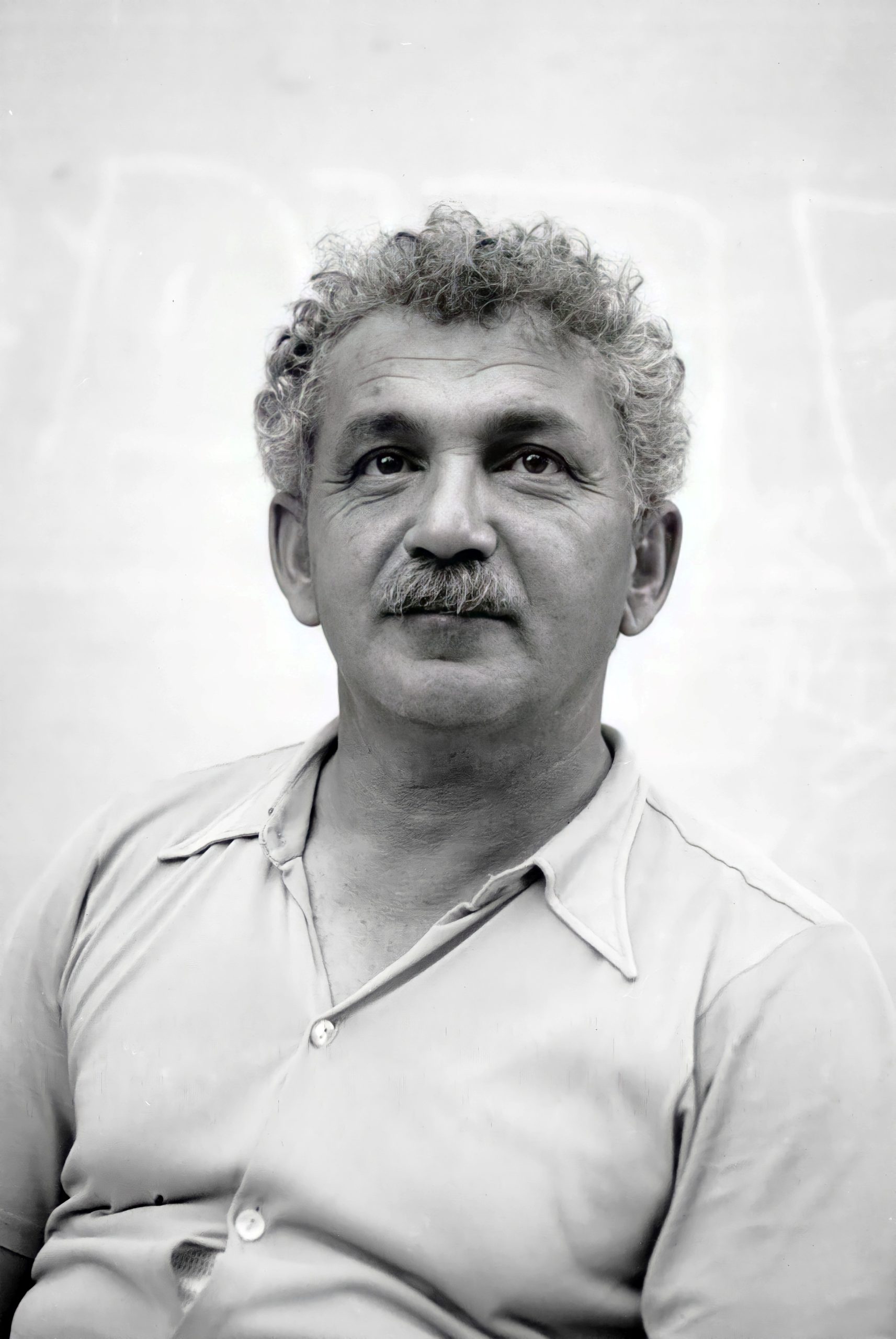

Shimon Peres was born in the village of Vishneva in White Russia. Long a part of the Russian Empire, the district was ruled by Poland between the world wars, and now lies in an independent Belarus. Like many of their neighbors, the parents of Shimon Peres were already committed to Zionism, the movement to secure a Jewish state in the historic homeland of the Jewish people.

As anti-Semitic violence escalated in central Europe, the family resolved to make the long-awaited move to the Holy Land. In 1932, Peres’s father traveled to the new Jewish city of Tel Aviv in British-controlled Palestine, to prepare the way for the rest of the family. Young Shimon, along with the rest of the family, joined his father in 1934. In all, half of the residents of Vishneva emigrated to Palestine. Those who remained behind, including Shimon Peres’s grandparents and uncle, were massacred by the invading Germans and their local collaborators during the Second World War. The Jews of Vishneva were locked inside their synagogue and burned alive.

In the land of Israel, young Peres became active in the socialist youth group Hanoar Haoved (Working Youth). At 15, he chose to study in an agricultural school, Ben-Shemen, which operated as an autonomous community of young people. Shortly after his arrival, he joined the armed underground, the Haganah, to defend the youth village from the frequent sniper attacks by its Arab neighbors. His writing and debating skills soon caught the attention of the leaders of the Mapai labor party, Berl Katznelson and David Ben-Gurion.

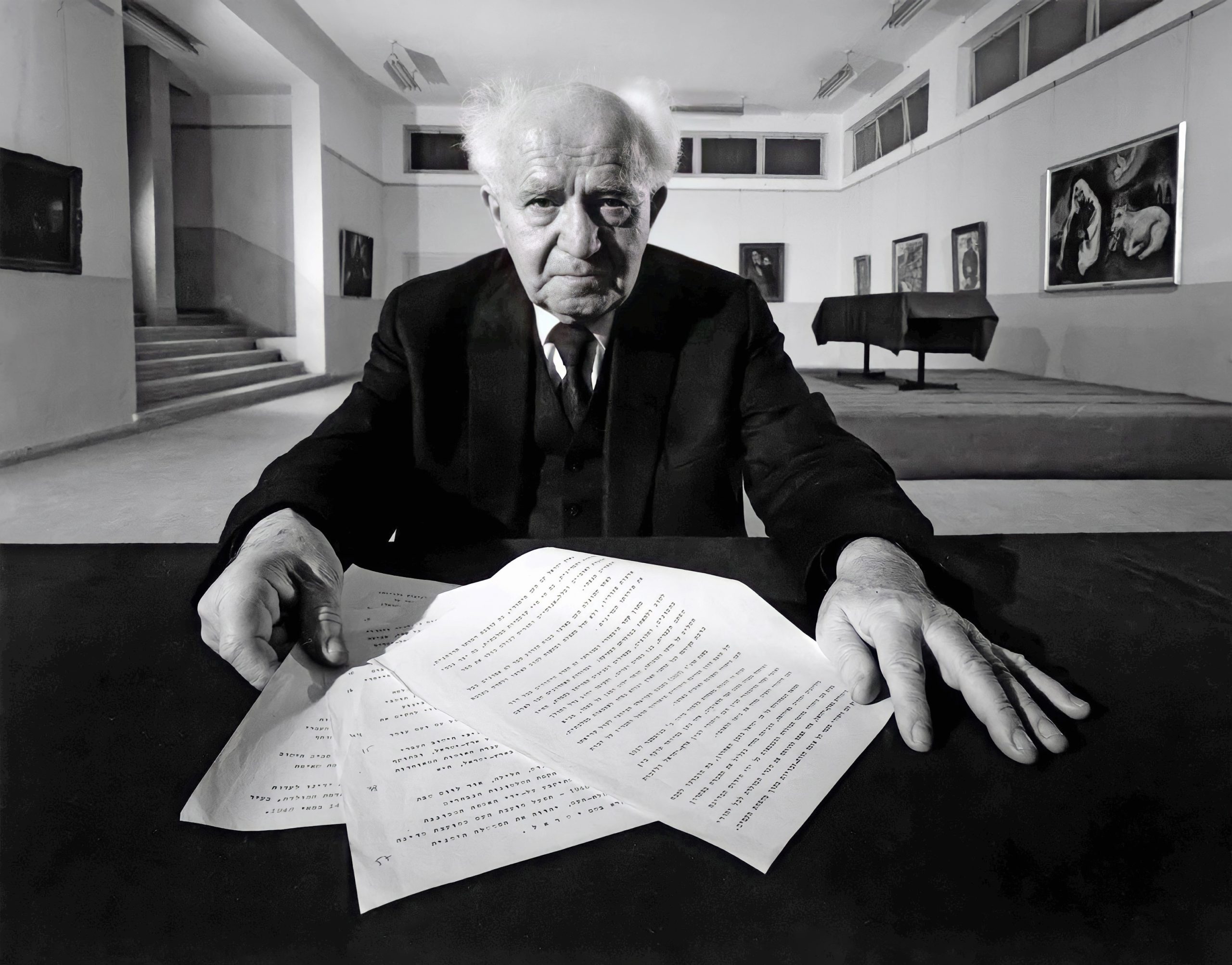

In 1947, the British resolved to leave Palestine, and the United Nations voted to partition the territory into an Arab state and a Jewish one. When the British withdrew the following year, and Ben-Gurion proclaimed the State of Israel in the land allotted it by the United Nations, seven Arab countries immediately declared war on the new republic. Although the United States and the Soviet Union both extended diplomatic recognition to Israel, they observed a complete embargo against providing arms to the new state, while the Arab states continued to receive arms from Britain.

Although young Shimon Peres was only a private in the new Israel Defense Force, he was assigned to the high command and given responsibility for areas including manpower, military intelligence and arms procurement, and was even tasked with directing the fledgling state’s tiny navy. Israel survived its first war, and settled into an uneasy truce with its Arab neighbors.

Shimon Peres served as director of the Defense Ministry delegation in the United States in the early 1950s, and continued his education at the New School for Social Research in New York City, and at Harvard. In 1953, at age 29, he was appointed Director-General of the Ministry of Defense. He carefully nurtured a relationship with the French government, which discreetly supplied the new republic with the arms it needed for its defense. As Director General, he helped oversee the dazzling Sinai campaign of 1956, led by his close political ally Moshe Dayan. He established Israel’s electronics and aviation industries and built Israel’s first nuclear power station at Dimona with French assistance.

In 1959, he first won election to Israel’s parliament, the Knesset, the beginning of a parliamentary career of over 40 years. Peres served as Deputy Defense Minister from 1959 until 1965, when a long-simmering conflict within the ruling labor party, the Mapai, led Prime Minister Ben-Gurion to break with the party and lead a separate faction, the Rafi, or Workers’ List, in the following election. Ben-Gurion’s closest followers, including Peres and Dayan, followed Ben-Gurion and served as minority members in the next session of the Knesset.

Over the next few years, Peres succeeded in mediating between Ben-Gurion and the rest of the Labor leadership. Along with another estranged faction, they formed a larger reunited Labor Party, Avoda, in 1968. Over the next years, Peres served as a cabinet minister in governments headed by Levi Eshkol and Golda Meir.

In the Labor government headed by Yitzhak Rabin from 1974 to 1977, Peres served as Minister of Defense. He led the Israel Defense Force’s recovery from the Yom Kippur War of 1973, and oversaw the disengagement of forces on the Egyptian front, laying the groundwork for the eventual peace settlement between Egypt and Israel. He also advocated for the military option that led to the successful rescue of a planeful of airline passengers from terrorists who had landed a hijacked airplane at Entebbe, Uganda. In 1977, Rabin resigned as Prime Minister and designated Peres as his successor. In the next election, Labor suffered its first electoral defeat, and Peres faced the arduous task of rebuilding the shattered party.

In the election of 1984, although Labor succeeded in winning the largest share of seats in the Knesset, it lacked the majority necessary to form a government on its own. Peres made the difficult decision to invite Labor’s principal rival, the Likud party, into a government of National Unity, in which Peres would serve as Prime Minister for two years, to be followed by the Likud leader Yitzhak Shamir for two years. Peres assumed power with inflation running at 400 percent annually. He mounted an all-out campaign against inflation, securing wage freezes from the labor unions, price controls from industry, and massive cuts from every department of government. In the first month after the plan was implemented, inflation dropped dramatically, and by year’s end had fallen to an acceptable level. As Prime Minister, Peres also effected the withdrawal of Israeli troops from most of Lebanon, and accomplished the airlift of thousands of Ethiopian Jews to Israel when a revolutionary dictatorship threatened their security.

At the end of his short term, he resisted the urging of his party comrades to break his agreement with the Likud party. He handed over the reins of power, as agreed, and served the National Unity government for the next two years as Foreign Minister. In this capacity, he negotiated secretly with King Hussein of Jordan, reaching an agreement he believes would have ended the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In the end, Prime Minister Shamir rejected the agreement, handing Peres one of the most painful disappointments of his long career.

The 1986 elections produced a coalition government led by the Likud. Peres agreed to serve as Finance Minister. In 1992, he lost a party leadership vote to his old comrade Yitzhak Rabin. The following election returned Labor to power, with Rabin as Prime Minister and Peres as Foreign Minister. This time, Peres achieved the two greatest diplomatic successes of his career, starting with the Oslo agreement between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization in 1993. Shimon Peres shared the Nobel Prize for Peace with Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat for negotiating this agreement. Despite the many setbacks the peace process has suffered since 1993, it still appears most likely that any future lasting peace in the region will be achieved through the framework of the Oslo Agreement. A peace treaty with Jordan followed shortly thereafter.

In 1995, Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated by an Israeli extremist opposed to the peace process, and Shimon Peres was once again called on to serve as Prime Minister. He served simultaneously as Defense Minister. After a fresh outbreak of violence, Peres narrowly lost a reelection bid in 1996. He served for another year as Chairman of the Labor Party, and resigned in 1997 to found the Peres Center for Peace, a nonpartisan, non-governmental organization dedicated to the promotion of peace in the Middle East. Over the course of his career, he wrote close to a dozen books on history, literature and politics, including his 1993 autobiography, Battling for Peace.

In 2001 and 2002, Shimon Peres served again as Minister of Foreign Affairs in a National Unity government headed by the Likud. Labor withdrew from this coalition in November of 2002. After suffering another electoral defeat in 2003, the Labor Party again called on Shimon Peres, now 79, to serve as its Chairman. In 2005, Peres was unseated as Chairman of the Labor Party. Within weeks, he electrified the political world by announcing that he was leaving the party he helped found, and announced his support for the candidacy of an old political adversary, Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, who had himself recently left the Likud to found a new, centrist party, Kadima. Peres maintained that the new party would have the best chance of achieving the long-sought peace settlement with the Palestinians.

When Ariel Sharon was felled by a stroke, Ehud Olmert assumed leadership of the Kadima party. In the 2006 election, Peres won re-election to the Knesset on the Kadima slate. Olmert formed a broad-based coalition government, with Peres serving as Vice Premier. In June 2007, the Knesset elected Shimon Peres to serve as President of Israel. On his election as President, Peres resigned his seat in the Knesset, bringing to an end the longest parliamentary career in his country’s history. As Head of State, the President’s role transcends the divisions of party politics. The election of Shimon Peres to the Presidency was the ultimate recognition of his lifelong service to his country. The Israeli constitution allows the President a single seven-year term. Shimon Peres completed his service as President in July 2014, a few weeks before his 91st birthday.

Shimon Peres was the last survivor of the generation of leaders that founded the modern state of Israel. When he died following a stroke at the age of 93, his passing was noted as the end of an era. His funeral in Jerusalem was attended by representatives of more than 75 countries, including President Obama and former President Clinton from the United States, the Presidents of France and Mexico, the Chancellor of Germany, two former British Prime Ministers, the Prime Minister of Canada, the King of Spain, and the President of the Palestinian Authority, Mahmoud Abbas. President Clinton in his eulogy, described Peres as a “champion of our common humanity. He started life as Israel’s brightest student, became its best teacher and ended up its biggest dreamer.” Clinton went on to say, “He lived 93 years in a state of constant wonder over the unbelievable potential of all the rest of us to rise above our wounds, our resentments, our fears to make the most of today and claim the promise of tomorrow.” Shimon Peres, a man who made a legacy of bridging divides, there was one final act of reconciliation: he was buried between two onetime rivals, Yitzhak Rabin and another former prime minister Yitzhak Shamir.

“When you win a war, your people are united and applaud you. When you make peace, your people are doubtful and resentful.”

For more than half a century, Shimon Peres served the State of Israel and the cause of peace with a courage and determination born of intimate familiarity with the horrors of war. He served in the defense forces at the founding of the State of Israel, heading the Navy at age 25; at 29 he was Director-General of the Ministry of Defense. Over the course of a 48-year career in Israel’s parliament, the Knesset, he held every major cabinet post and served as Prime Minister in some of Israel’s darkest hours.

He first served as Prime Minister in 1977, after the resignation of Yitzhak Rabin. In 1984, he headed a National Unity government that put an end to a ruinous inflation, and extricated Israel from a torturous military involvement in Lebanon. As Foreign Minister he initiated the negotiations that led to the Oslo Accords with the Palestine Liberation Organization, and completed a long-sought peace treaty with Jordan. In 1994, he shared the Nobel Price for Peace with Yasser Arafat and Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. Upon Rabin’s assassination, Shimon Peres became Prime Minister once again, serving simultaneously as Minister of Defense. He later served yet again as Foreign Minister in a government of National Unity.

For many years he endured criticism, even within his own Labor Party, for his zealous pursuit of peace, but his determination never wavered. He has always placed the welfare of the nation as a whole ahead of partisan interest. At the age of 82, after serving another term as Party Chairman, he left the Labor Party to support a new centrist formation committed to a negotiated peace with the Palestinians. In June 2007, he was elected to serve as the ninth President of Israel, the country’s official Head of State. He was the first former Prime Minister to attain the Presidency of Israel, but long before winning this honor, Shimon Peres had won a place in history as one of his country’s greatest statesmen and one of the world’s great champions of the cause of peace.

Can you tell us how you approached the negotiations that ultimately led to the Oslo Accord with the Palestinians, and your winning the Nobel Peace Prize? It seems you were learning and listening where other people might not.

Shimon Peres: At the beginning, I thought that we have to make peace with King Hussein. That would eventually represent both the Jordanians and the Palestinians. I think by geography, and the reason — we are a triangle: Jordan, Palestine and ourselves. So I went and negotiated with King Hussein secretly, and we reached an agreement. The rest of the negotiations took place in London, at a private home of a friend of the King and a friend of mine. I remember that the wife of this person, who is a lawyer, sent away all of our staff, and she cooked herself, and at the end of the dinner, I suggested to the King that we should go and wash the dishes — and the King was so happy to do so, but she wouldn’t let us, so we didn’t do it. Anyway, we sat for eight hours, and we worked out our agreement. I think this was the best agreement we ever had. But at that time, we had the National Unity Government, 50 percent Likud and 50 percent us, and the Likud Party did not agree, so we lost maybe our best opportunity for peace, to my deep regret.

Then I thought, “My God, we don’t have a choice but to negotiate with the Palestinians, with the PLO, with Arafat.” We had many contacts with the PLO people, but I noticed, like many people in exile, they have a tendency to make from every problem an ideology, and from non-ideology a solution. So you argue and argue and argue endlessly.

I was looking for a person among the Palestinians who can come down to earth, because the arguments are well-known by both sides, and it’s almost a waste of time to begin and blame and accuse and demand. Then, among the many contacts, there was one person that — I asked him to do something which for me would be a test, and for him very difficult. You know, we have had two levels of negotiations, one directly with the Palestinians, and the other which is called the “multinational negotiations.” One was about the borders, and the other was about the relations, with the participation of many nations. Practically everybody participated. One of those groups was dealing with refugees, headed by a representative of Canada. We were supposed to nominate a person to represent our side, the Palestinians a person to represent their side. The Palestinians nominated somebody who was a member of the PNC, Palestinian National Council. According to law, we weren’t permitted to negotiate through the PLO. So I approached this person (Abu Alaa, also known as Ahmed Qurei) and said, “Look, do you want to negotiate, do you want to be serious? Replace your man.” And instead of him saying, as usually anybody would say, “It’s impossible. Forget it,” he said, “I shall try.” And it didn’t take much time. He replaced him. So I told myself, “That’s it. He’s the man.” Because you know, it’s one thing to win arguments, and another thing is to arrive at solutions.

The Prime Minister was Yitzhak Rabin. He was conducting the negotiations that took place in Washington. I told him from the outset that nothing would come out of it, because after every meeting, there was a press conference. You know, negotiations and lack of discretion is like trying to make love in the middle of the street. There are things that you have to keep in the dark. I told him about this man I knew, Abu Alaa. I said, “Let me try with him.” He wouldn’t believe it, but he says, “Okay, try it.” And while the negotiations in Washington deteriorated from day to day, our negotiations in Oslo went up from day to day. Finally, the negotiations in Washington fell down, and the negotiations in Oslo came to fruition.

We did it, half-legally, because there was a decision by our parliament that we should not negotiate with the PLO. I wanted to go to negotiate directly with them, but Yitzhak Rabin told me, “Look, it would be very strange if the Minister of the Cabinet is breaking the law.” So I sent my Director-General of the Foreign Ministry, Uri Savir, who is a brilliant chap. He went together with an Israeli lawyer, who is also a brilliant lawyer. They met with the man I was mentioning, Abu Alaa, who is now the Speaker of the Palestinian Assembly, who I believe is probably the most intelligent man that I can think of among the Palestinians.

The two of them established a chemistry immediately, Abu Alaa and Uri Savir. What they were telling each other, nobody knows. It’s really like a romantic experience. You have to seduce, you have to impress, and very often to close a little bit your eyes, because if you see everything too naked, you may lose your taste.

The last night before the (Oslo) agreement, which was August 1993, also happened to be my birthday, so I was a little bit emotional. They reached a breakdown. And then, we negotiated through the telephone with Arafat and myself, eight hours. They were in Sweden, he was in Tunisia. And there was Mr. Larson from the Norwegian side and the late Foreign Minister of Norway, Holst. The telephone was so good, I could hear their cries, I could hear their suffering. I shall never forget this experience. Shall I say it’s like a lady giving birth to a child? The pains, the hopes. And early in the morning, we reached an agreement by phone.

Then the Norwegians organized a secret meeting for signatures, because still the Cabinet didn’t approve. I was there, and the room was filled by the Secret Service of Norway. We wouldn’t let anybody else enter it. The day before the signing, there was a clash with the Hezbollah in Lebanon, and nine soldiers of our army lost their lives. The contrast was so great. We had prepared champagne and an environment of happiness — and nine boys were killed. So I called up Rabin, and I said, “Look, I know exactly how you feel. We lost nine boys. Maybe the best thing will be to postpone it. We cannot celebrate this agreement tonight.” Rabin thought for a while, and with his very deep voice, he said, “No. We shall sign.” But we removed the champagne and all the other niceties and made it a dry meeting.

At the end of the signatures, Abu Alaa asked to see me privately. Before he said a word, he burst into tears like a child. There was so much emotion in these negotiations. I was taken by that, I was surprised. Then he said nice things about the fate of his people and about the way we ran it and behaved.

I know many people criticize Arafat for good reasons. He was an impressive leader of the Palestinian revolt, and a failure of the Palestinian state. I for one will never forget the courageous steps he took, and there is no occasion whenever they attack Arafat that I wouldn’t come on his side and say, “Don’t forget the courageous decisions he has taken.” And I would like to mention just one. With all Arab states, the basis of our negotiation was the United Nations Resolution about the 1947 borders. Would we make it a basis for our negotiations with the Palestinians? Fifty-five percent of the land was to go to the Palestinians, 45 to us. So it wouldn’t fly. Arafat agreed to the 1967 borders, which gives the Palestinians only 22 percent and Israel 78 percent. I don’t know of any other Palestinian leader that would do it, that was able to do it and ready to do it.

You must be fair in your life. I criticize Arafat very much. I think, later on, he spoiled what he has achieved, but still, I remember what should be remembered as well. On the other hand, we on our side went a very long way, because the West Bank was under Arab rule. They never gave it to the Palestinians. Gaza was under Arab rule. They never gave it to the Palestinians. We did it. We helped them to build the Palestinian personality and eventually the Palestinian state. As I remember the role of Arafat, I don’t regret the choice we made at that time.

The Nobel Prize was given also some years later to those who tried to forge peace in Northern Ireland. Do you see a parallel in the sense that you are still striving for a complete resolution?

Shimon Peres: I don’t think so. When you make a breakthrough, things don’t happen automatically and instantly. But without a breakthrough, it would be just a wish in the air.

Every important decision has to go through a long avenue of disappointments, of setbacks, of troubles. I am totally unimpressed. I would be surprised if it would go smoothly. Somebody said, “You are as great as your crawl.” If you want to achieve something important, you have to fight and crawl for it under very uncomfortable conditions and circumstances. And then again, when you win a war, your people are united and applaud you. When you make peace, your people are doubtful and resentful. To negotiate peace is to negotiate with your own people, not with your opponent, and your own people say, “My God, why did you give up so much? Why were you in a hurry? Why didn’t you think this and that?” Well, if you think this and that, and you won’t be in a hurry, still you have to pay the price, because peace has a price as war has a price. The difference is that the price of war is unavoidably accepted. The price of the cost of peace cannot be measured.