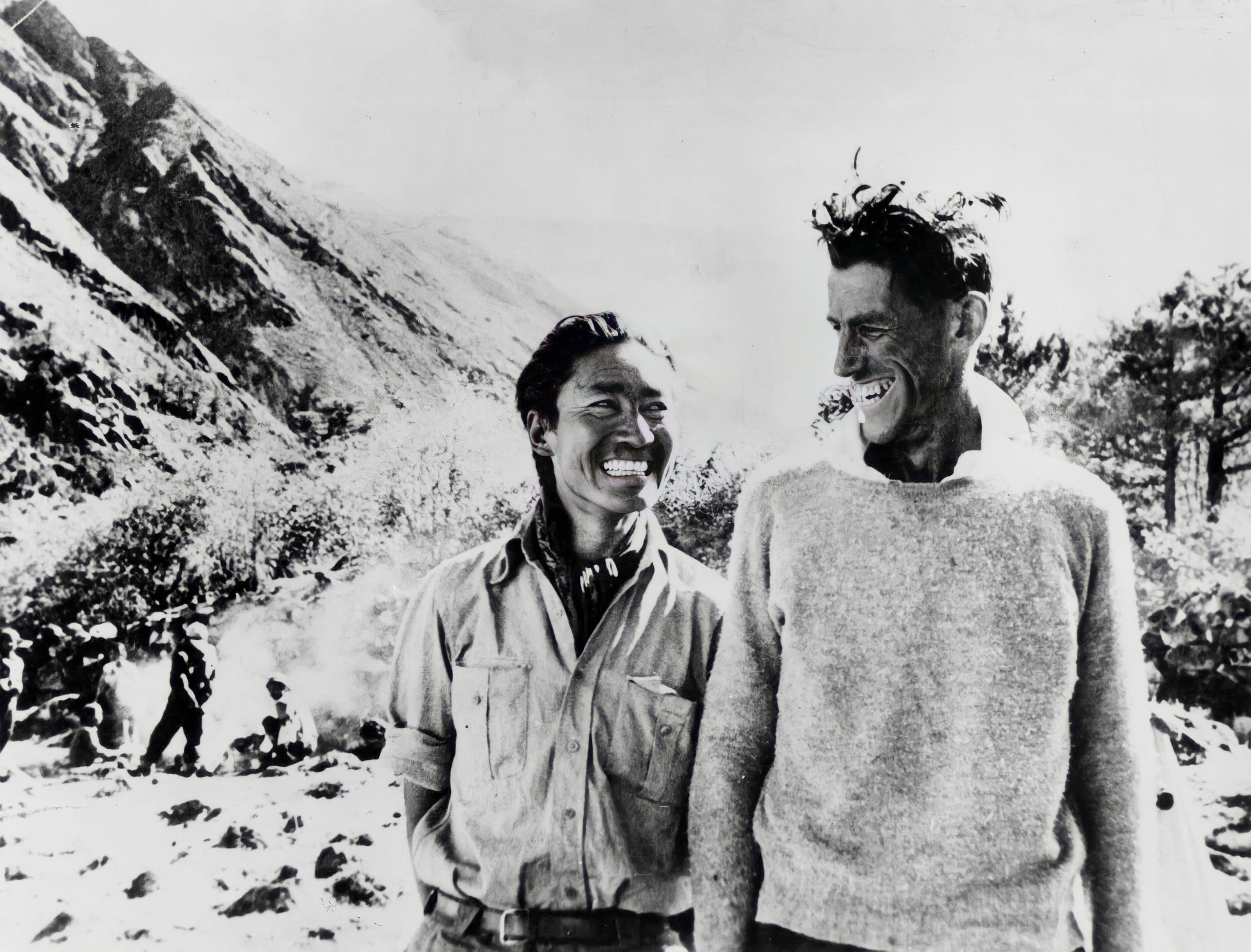

We have this romantic idea that when you reach the top, it’s some kind of glorious, conquering feeling, and yet there must always have been in your mind, “Gee, we’ve got to get back down again.”

Sir Edmund Hillary: In lower mountains and Alpine areas, I have had a great sense of excitement and achievement at reaching the top of a difficult peak. On Everest, due to the lack of oxygen, life is at a low level as it were. I certainly did not have that tremendous feeling of wanting to jump around with joy or anything of that nature. I was just very happy to be there and felt very satisfied that we’d finally succeeded in getting there.

How would you describe to somebody who didn’t understand anything about climbing or anything about the feeling of adventure, what the excitement of your adventurous career is like?

Sir Edmund Hillary: I think I’d try to find out what the things are that made them excited. It doesn’t matter what field you’re in. You could be in education, science or business. Almost anything has its moments where you have to overcome considerable challenges, and if you’re able to overcome those challenges, you get a great sense of satisfaction. And I would say a businessman who’s been able to achieve a successful deal of some sort, would probably feel a very similar sort of reaction to someone who’s just managed to get to the top of a mountain. You’ve overcome problems. You may not have been frightened to death, but you’ve overcome problems and difficulties and you’ve achieved success and you certainly feel pretty happy about it.

I think the element of danger which is present in things like mountaineering and sailing around the world and all those type of things, does add a tremendous amount to the challenge. There’s simply no question that if you’re doing something that has the possibility that you may make a mistake or something may go wrong and you’ll come to a rather sticky end, this I think, does add something, really, to the whole challenge. You really feel you’re doing something exciting and perhaps a little desperate, and if you’re successful, it certainly gives you that little bit more satisfaction.

What is it that made you enjoy walking on the edge?

Sir Edmund Hillary: I don’t really know. When I was very young I read about it, dreamed about it and when the opportunity came to do something about it I seemed to slip into it rather easily. Even the companionship that I made with similar friends in adventurous activities, I found very, very rewarding. Nothing is better fun that sitting down with a group of your peers who’ve done similar sort of things and just talking about your experiences. Maybe boasting a little bit here and there too, but sharing experiences that you all appreciate, you all know have been frightening and dangerous and have been successful.

You’re very physically fit and yet you’re in your 70s, so I imagine that you have come to a point in your life where you know that you’ve had to leave certain things behind. Has that been a tough adjustment?

Sir Edmund Hillary: I’ve been very fortunate in that respect. In the early days I liked to be the bomb of the expedition, and rush on ahead and do things faster than anybody else. Those days merged very pleasantly into periods when I organized and inspired expeditions and selected these younger people who were then the bombs of the operation. And then it drifted into this involvement with the people of the area, still loving the mountains, but finding the people just as important too. And on and on it’s gone. As I get older and less physically capable, I find other challenges have grown up and become just as important to me.

Of course, we’re all unique and have our own paths, but kids sometimes get so confused and feel they’ve got to be like somebody else. How would you encourage young people to find their own way?

Sir Edmund Hillary: The only way to encourage them to find their own path is to tell them that, in my view, that’s the only way in life. It’s one of the things I really like about Tibetan Buddhism. I have no particular religious beliefs at all, but I am interested in all religions. In Tibetan Buddhism, one of the strongest features is that they believe that everyone must choose their own path in life. They don’t try to convert you to their particular form of religion, but it’s up to you to choose your own path. I like that very much indeed. I think that’s a great approach to philosophy. I think that we have to learn to choose our own path, to make our own way, and in many ways, to overcome our own problems. There are many people who, when they’re in a moment of danger, will resort to prayer and hope that God will get them out of this trouble. I’ve always had the feeling that to do that is a slightly sneaky way of doing things. If I’ve got myself into that situation, I always felt it’s up to me to make the effort somehow to get myself out again and not to rely on some super-human human being who can just lift me out of this rather miserable situation. That may be a slightly arrogant approach, but I still feel that in the end, it’s up to us to meet our challenges and to overcome them.

Do you remember some incident that was extremely dangerous for you, where someone else may have prayed for help, where you took responsibility?

Sir Edmund Hillary: Well I have no doubt at all that, when I’ve been on slightly questionable expeditions, people have prayed for my welfare, but I certainly haven’t.

Can you describe a particularly dangerous or challenging incident where you have had to rely on yourself, where someone else might have chosen to pray?

Sir Edmund Hillary: Well for instance, coming down from Nupla Pass on one occasion in very difficult conditions, through crevasse country, I stepped on a piece of snow which happened to be a thin bridge over a crevasse and I shot through the thin bridge and started falling into the depths of the crevasse. Well my thoughts, which were fairly quick at the time, were just, “How can I overcome this?” Almost instinctively, because the crevasse was relatively narrow, I kicked my feet out towards one wall of the crevasse, and on my feet I had these spiked crampons, so I jammed my feet against the wall into the ice and then my shoulder bridged the crevasse, and I stopped. There I was, half-way down the crevasse with my feet against one wall and my shoulder against the other. I held onto my ice axe which, after all, any good mountaineer is told to do, and ultimately, I was able to use my ice axe to chip steps in the ice and get safely out.

Now I really felt under those circumstances that it was up to me to get myself out of this unfortunate predicament. I didn’t really feel that it would have done me all that much good calling on some great being to suddenly lift me out of this unfortunate situation.

I think even people who do pray in situations like that know that they have to help themselves.

Sir Edmund Hillary: Oh yes. People who feel they get strength from prayer, of course, should use their prayer.

Everyone knows you for climbing Mt. Everest, but what’s your life like now?

Sir Edmund Hillary: My career over the years has slowly grown and changed, but I’ve retained a vast amount of the interests that I had in my early days. I’ve moved from being a child who dreamed a lot and read a lot of books about adventure, to actually getting involved in things like mountaineering, and then becoming a reasonably competent mountaineer and going off to the Himalayas, doing a lot of climbing, and going off on expeditions to the Antarctic and that sort of active adventurer stage. Then I, more or less as I got older, I moved into a period where I was more involved in organizing, raising funds and leading expeditions. I was sort of the motivating factor in the expeditions, but perhaps less active. I wasn’t the hot shot heading for the summit; I had other members of the party who did it. As I got somewhat older, again I became increasingly interested particularly in the people of the Himalayas. I built up very close friendships with them and I became concerned about the things that they wanted: schooling and hospitals and things of that nature. This carried on for quite a while. Perhaps in more recent years, certainly in the last 15 years or so, I’ve also become very much involved in environmental matters. So I would say now that my major interests are in people and in the environment.

Can we go back to that young Ed that read a lot of books and dreamed? What were some of the dreams you had?

Sir Edmund Hillary: My dreams were almost all adventurous dreams. I suppose in many ways, I was not lonely, but I didn’t really have many friends, and I used to go on long walks. I was a very keen walker and, as I walked along the roads and tracks around this countryside area, I’d be dreaming. My mind would be miles away and I would be slashing villains with swords and capturing beautiful maidens and doing all sorts of heroic things, just purely in my dreams. I used to love to walk for hours and hours and my mind would be far away in all sorts of heroic efforts. I never really felt that this was going to take place in quite that way. I think I was reasonably practical in that sense, but I rather enjoyed this dreaming phase. And certainly, I was also a very great reader, and the books I read were initially, very largely on the adventurous sort of activities. The Warlord of Mars or Georgette Heyer and those sort of romantic adventure type things. When I was going to high school, I lived right out in the country, but I went to a big school in the city and I had to travel about two hours each day, each way, to school, so I was on the train about four hours a day. I used to get a book out of the library every day, so I was reading a book a day for quite a number of years. Most of the books had some adventurous slant, so I guess these books tended to stimulate periods when I dreamt about doing all these things. I wasn’t really doing anything at that stage, but I was certainly reading about it and dreaming about it.

When did you start to make the transition between dreaming about these adventures and actually pursuing them?

Sir Edmund Hillary: When I really started getting going, was when I was 16 years old. It was high school and I went with a school party about 250 miles south of Auckland, where I lived, down to our national park area where there were a number of big volcanic mountains and there’s lots of snow there. It was the middle of winter and there was snow everywhere. It was really good, heavy snow. This was the first time I had ever seen snow, because we don’t get it in Auckland, and for ten days I skied and scrambled around the hills. For me, it was the most wonderful experience I’d ever had up to that stage, and I think it really was the beginning of my enthusiasm for mountains and for snow and ice. In fact, it was really the first real adventure I’d had. It built up, even at that early stage, a very strong affection for mountaineering. I knew I could do it and enjoy it and so it grew on me. Of course, after that I did a great deal more.

Did you tell anyone how excited you were with the snow and your adventure?

Sir Edmund Hillary: Yes, when I came home. I was quite good at relating slightly exaggerated stories of my adventures. Certainly my brother and sister and my parents were pretty patient about it. They listened with interest, but I’m inclined to think, in looking back, that I actually told quite a good story, so that they found my discourses quite interesting. I was doing things that they, at the time, weren’t doing, and so I think I did impart this growing enthusiasm to them.

Who encouraged you? Did you have any teachers or any aunts or uncles or neighbors that encouraged you to continue being adventurous?

Sir Edmund Hillary: Not really. I had a number of friends who were interested in tramping and trekking around our local hills, but as I got older, I discovered that I tended to be rather more energetic and stronger walkers than they were and so…I always seemed to be pushing young ladies up steep hills and clamoring up trees to find out where we were. And I sort of quickly became pretty active in that sort of way. I still wasn’t doing anything of great consequence, but I was loving the out-of-doors and loving forcing myself to travel quickly around the countryside and do very long treks and I enjoyed it very much.

At that point in your life, what did you think you were going to be when you grew up?

Sir Edmund Hillary: I really had no idea whatsoever. I feel that my life developed as I went along. I was never one of those people who, at an early age, had picked an objective and worked steadily towards it. All I knew was that I wanted to get involved in adventurous activity. I didn’t have any specific type of activity in mind, but I wanted to do things that were exciting and adventurous. I had a fairly diffused feeling as to what precisely it should be.

Did you have any heroes or role models when you were growing up?

Sir Edmund Hillary: I did have — definitely — one heroic figure who impressed me very much indeed, and that was the great Antarctic explorer, Shackleton. Shackleton I always admired because he was a tough man and a very good leader. And whenever he was in difficult circumstances, which he frequently was, he seemed to have the great ability to inspire his men and lead his party safely out of those conditions. So certainly Shackleton, I would have said, more than anything, was a role model for me. And later on, when I was down in the Antarctic myself and doing various adventures, I really felt that I tried to behave perhaps a little bit more like Shackleton, than any of the other famous Antarctic explorers.

Behave in what way like him?

Sir Edmund Hillary: Shackleton was a man who was prepared to make a decision and change his mind quickly. There are a lot of very successful explorers who choose their plan and their path and stick to it very closely indeed, following it very methodically through. This was not the attitude of Shackleton and certainly wasn’t my attitude. The main objective remained, but there were always a multitude of alternatives of how you achieve these objectives. So, I was the sort of, Antarctic explorer. If someone came up with a good idea, I was perfectly prepared to accept it. A lot of people who are leading an expedition, if someone produces a good idea, they refuse to accept it because they feel it’s letting themselves down, but I was happy to accept anybody’s idea and to absorb it and take it over and use it, and usually they were pretty good ideas. I was always prepared to — if the circumstances seemed suitable — change a complete plan, to go in a different direction or use a different method. In that sense, I think, I admired Shackleton. He was very adaptable, and I tried to be very similar.

Did that have to do with an intellectual decision or listening to, as they say, your gut, your intuition?

Sir Edmund Hillary: I think it was a combination of feeling and judgment. I happened to be that sort of person that enjoyed making out plans, but I also enjoy changing plans. On an expedition, although I may start out with a detailed plan, I’m prepared to change it at any moment and completely redo it. So our expeditions turned out to be very adaptable ones. We achieved the final objectives just the same as many other expeditions, but maybe we had more fun in the process because it seemed something we could vary. We still carried on to achieve our major objectives.

I know your family business was beekeeping. Were you expected to go into that business?

Sir Edmund Hillary: We weren’t expected to go into to it. My father was the editor of a country newspaper, so he was very much involved in press activities. My mother was a school teacher. My father took over a newspaper in a small country town. It had the grand name of the Tuakau District News and it was very small. He did everything. He was the reporter, he went to all the football matches and reported on them. He knew everybody in the whole area. He would write the articles and set up the actual type, as you used to have to do in those days. We had a printing press in a shed on our small farm, and he printed the newspaper. In fact, I think the only thing he didn’t do was deliver it ’round to all the houses in the area. He was, in his own way, a very resourceful individual.

My parents also were people of very strong character. They had strong principles, as many people did in those days. It was during the early days of the Depression and my father felt very strongly, indeed. There was a period when food was being destroyed in order to keep the price of food up, and yet there were thousands, millions of people going short on food. That type of thing really irritated him. He thought that was completely unjust. Although I was not aware of it at the time, I think I was brought up to this feeling that it was important to be interested in the welfare of other people and other people around the world, really. My mother used to say to me a thing which, when I look back on it, wasn’t terribly logical. — and I had a pretty hearty appetite, but when I had had a large meal put in front of me, and even I couldn’t get through it, she would say, “Edmund, remember the starving millions in Asia.” Now what possible use my consuming it would do for the starving millions in Asia, I don’t really know, but the fact remains that I was brought up to think about the starving millions in Asia. That meant I had to clean my plate up and not waste it. Later on, I got more involved with the starving millions in Asia, perhaps in a slightly more practical way: helping some of them with schooling and hospitaling and even in agriculture.

So a lot of your values came directly out of what your family demonstrated.

Sir Edmund Hillary: Yes they did, and I really wasn’t aware of it at the time. I didn’t analyze what my parents were doing and say, “That’s a good thing, I must do that when I get older.” Those sort of thoughts never entered my mind, but I was definitely brought up in an atmosphere where my parents had these firm convictions. They had very strong ideas about what was right and wrong and all the rest of it. I had great arguments with my father as a consequence but, I don’t think there’s any question at all, a great deal of what I would regard as very good, sound philosophy, almost unconsciously, was handed on to their children.

How did your parents feel about your lust for adventure?

Sir Edmund Hillary: I don’t think they really cared too much. In fact, I don’t know that they knew it was going on. They knew that I used to love going on long walks, but I’m sure that they didn’t realize what I was dreaming when I was doing it. They were aware that I was a very keen reader, but they thought that was a good thing anyway. They certainly didn’t supervise the type of books which I read. I would have said my reading tended to be the lighter, more adventurous type of thing. I wasn’t a great reader of Shakespeare and things of that nature, although I had to do it at school. I think they pretty much left me alone in that respect.

Did you feel you were different than other kids? Did you feel that you were gifted or smarter?

Sir Edmund Hillary: No. I knew I wasn’t smarter than other kids. In fact, when I first went to high school, I was a relatively lonely child. I didn’t really have any friendships there. I started off in high school a couple of years younger than the majority of the students, because at the little country, primary school, where I attended, my mother, who had been a school teacher, sort of coached me, and I became the child genius of the Tuakau primary school, which I can assure you, was not all that big a deal in those days. For the small Tuakau primary school, I sort of skipped a few classes and then I finally went to high school when I was 11 instead of the normal age of 13 years. Coming from a country area, going into a big city school which, academically, is probably the best school in New Zealand was quite a shock to me. I was younger and smaller than the other students, and I really had no friends there whatsoever. For a year or two, it was quite difficult for me. It was a lonely existence and I certainly didn’t particularly enjoy it. I started growing then. I remember, in one year I grew six inches and the next year I grew five inches, which is not uncommon with kids of that age. Suddenly, I started getting bigger and I was bigger than lots of my fellow students and I became more physically competent. So I gained confidence in that way. But I was always a modest student. I was sort of in the middle. I wasn’t awful and I wasn’t good, but I was adequate.

Did you work on developing yourself, then, physically, getting ready for the kind of career you would pursue?

Sir Edmund Hillary: I did find that I was getting increasingly physically active. I was never what you would call a great athlete, in the sense that an athlete has a tremendous eye and tremendous ball sense and great speed of movement and that sort of thing. I was more the rugged, robust type, and I was physically strong. I was also pretty strongly motivated. Even in those early days, if I started out to do something, I generally ended up by getting pretty close to completing.

Let’s talk about motivation. Obviously, your life has had a lot of self-motivation.

Sir Edmund Hillary: I think motivation is the single most important factor in any sort of success. Physical fitness is important, technical skill is important, and maybe even the desire for money is important in some respects. But a sort of basic motivation, the desire to succeed, to stretch yourself to the utmost is the most important factor. Certainly in the field of exploration and activity, it’s the thing that makes the difference between someone who does really well and someone who doesn’t.

Let’s talk about motivation and things that aren’t necessarily accomplished the first time. When you don’t get the encouragement, how do you keep your motivation going?

Sir Edmund Hillary: I’ve always felt that it’s far more important to set your sights high. Aim for something high, and even fail on it if necessary. To me, that’s always been more impressive than someone who doesn’t ask for very much and achieves it. That’s not a great deal of satisfaction, in my view. I’ve always tried to carry things through to a conclusion once I’ve started them. Setting your sights high and extending what were — in my case — modest abilities to the utmost… If you succeed, you certainly get a tremendous sense of satisfaction.

You see yourself as just having modest abilities?

Sir Edmund Hillary: I have very modest abilities. Academically I was very modest. Mediocre perhaps, and I think perhaps physically I did not have a great athletic sense, but I was big and strong. But, I think maybe the only thing in which I was less than modest was in motivation. I really wanted very strongly to do many of these things and once I started I didn’t give up all that easily.

What about failures? Have you had any? And what did you do with that experience?

Sir Edmund Hillary: Well, it sounds arrogant, but I can’t remember having all that many failures in major things that I set out to do. Sometimes objectives almost changed during the course of something you were attempting to do. You would decide that a more important objective was such-and-such a thing, rather than what you had initially set out to do. But I think on the whole, I have been able to carry through the majority of my projects to some successful conclusion.

What person or experience solidified the idea in your mind that adventure was going to be a career, not just a hobby?

Sir Edmund Hillary: I still regard adventure pretty much as a hobby to tell you the honest truth, and I think this approach to it keeps one refreshed almost. I think if you just regard adventure as a business, working becomes very boring as many other businesses can become. But even though adventure changed my life considerably, both in what I was doing and even economically, I’ve always regarded myself in a sense as a competent amateur. Because of that, I think a freshness has been brought to it, that every new adventure has been a new experience and great fun. I really like to enjoy my adventures. I get frightened to death on many, many occasions but, of course, fear can be, also, a stimulating factor. When you’re afraid, the blood surges in the veins and so on. If you get rigid with fear, quite obviously, fear is not a very satisfactory characteristic to have, but if it’s a stimulating factor, then I think you can often extend yourself far more than you really believe is possible. And instead of being just a mediocre person, for a moment anyway, you become someone of considerable competence.

You’ve used the words “fear” and “mediocre” several times. You have written that the mediocre can succeed and the fearful can achieve or accomplish. Will you talk about that?

Sir Edmund Hillary: I do remember writing that, and that’s just about the way I’ve felt about things. I know that in many ways, I’m basically a very mediocre person. I know I’ve been afraid on many occasions, but I also know that if your abilities are fairly modest, there are ways in which you can use them effectively. I think, for instance, that prior planning of what you’re doing, slowly and carefully working out how you’re going to meet problems if they arise, can be enormously helpful. If an emergency arises, you’ve already thought out the type of thing that you can do and the type of decisions you can make, the type of orders you can give, and overcome that problem and get through. I always have, in my expeditions, people who are academically far cleverer than I am, and even technically, far more competent. So if you want to lead an expedition, in a sense, you’ve got to keep ahead of them. These bright, competent characters you have with you who are marvelous to have on the expedition. And I’ve always found you can do that by, each night, when you go to bed, just let your mind dwell on the likely things that may happen next day, and think out carefully the sort of decisions that might be necessary to make in order to have the program carried through. So next day, when something happens, you’re the one that’s thought about it and you’re the one who has the ideas. Whereas all the brighter ones really haven’t spent too much time thinking about it. They have to produce it quickly out of their minds and sometimes their ideas, of course, are very good, but for a mediocre person like me, if you pre-planned it and thought it out, then you can give sound decisions on pretty short notice.

The qualities you mentioned, soundness and mature judgment, they’re the qualities of leadership. So what you’re really talking about is how you developed as a leader.

Sir Edmund Hillary: There are some people who are natural leaders, who have the ability to think quickly or choose the right decisions at the right moment. But I think there are an awful lot of us who have to learn how to be a leader, and in actual fact, I believe that most people, if they really want to, can become competent leaders. I think I was the prime example of someone with relatively modest abilities, but I think I learned to become a reasonably competent leader. Even practice is quite a useful attribute in this respect. As you do more expeditions and more adventures, you get more experience and you know more clearly what to do in moments of emergency. But I certainly never regarded myself as a natural leader.

I can always remember, when I was at high school we had a school sort of army battalion and because, at that time, I was one of the larger boys, I was appointed sergeant of the number one platoon, and I was always absolutely petrified that when I was meant to turn the platoon left or turn it right, I was really actually hopeless at knowing quite what to do. But fortunately, my platoon, who were really all the misfits in the school, the larger misfits, they stood by me, and some of them were quite good at knowing when to turn left or turn right. So whatever command I gave, they would do the right thing. We were a pretty good platoon as a consequence although, at the time, I felt an absolute idiot. Some of the suggestions I made, my platoon ignored and did the right thing. But maybe I had a good rapport with them and, as a consequence, we were working together pretty much as a team, and we usually did the right thing. But I certainly was completely, often, at a loss as to what was the correct thing to do, but because of the feeling that I had with my platoon, we usually ended up by doing what was right.

How do you think you developed this healthy balance between being part of a team and being an individual striver?

Sir Edmund Hillary: I did my best. I certainly had strong individualistic attitudes, and I think probably I was at my best when I was given the job as leader of a project. In other words, I was forced to think ahead and make decisions and make sure that everything was carried out successfully. I don’t think I was a very good follower because I think I did have my own personal ideas and I didn’t particularly like being ordered around, to tell the truth. On the other hand, as a leader, I was not the type who ordered other people around. I did expect my groups to have good, strong ideas of their own, but for us all to work happily together and I think, on the whole, our expeditions were very happy ones and that we had quite strong team spirit.

The press and the public rather think of you as a star and yet you think of yourself as a member of a team.

Sir Edmund Hillary: The press and the public have created an image of Ed Hillary, hero and explorer which simply doesn’t exist. They’ve painted a picture of me as a heroic type, full of enormous courage, tremendous strength, undying enthusiasm and all the rest of it. But it’s all really just a story, that’s been written up in the newspapers. I’m a person, as I’ve said, of modest abilities, with a good deal of determination, and I do quite a lot of planning ahead. With careful planning and good motivation, I think you can often achieve things that other much more talented people would probably do much more easily. But then, a lot of these very talented people are not strongly motivated to carry out the things that I’ve been involved in.

What’s the proportion of skill, planning, leadership and luck?

Sir Edmund Hillary: You need all those things of course. You certainly need planning and you certainly need a degree of skill and fitness, and there’s no question at all that you need a little bit of luck. People often say you make your own luck, and I think probably 90 percent of the luck is self-created, but there is that ten percent. You’ve got to have things right at the right time. If you’re heading for the summit, you’ve got to have a reasonable day for it. And if the weather doesn’t treat you right, nobody’s going to get there. I guess you’d call that luck. But if you plan things, maybe you’re organized so you can wait for another day and put in your push to the summit. But I do believe that a little bit of luck is a good thing to have.

Have there been many situations where you’ve been criticized, and if so, what did you do with that experience of criticism?

Sir Edmund Hillary: There have certainly been occasions in which I’ve been criticized. When we were doing our Antarctic trip and Manny Fuchs was crossing over the continent and we were putting out loads towards the Pole, and we headed off toward the pole and we actually reached the South Pole several weeks before Fuchs, which was never in the original plans. But we had carried out all the laying of depots which had been in the plans, and I had managed to acquire a dozen extra drums of fuel with the idea that once the task was completed, that we might head off for the Pole. There was a little bit of criticism in the media, particularly in Britain that we had “Won the race to the Pole,” as they called it when we really weren’t meant to do it. I don’t think I really took that terribly seriously, because never at any stage had it been suggested that we shouldn’t go to the Pole. It had never been in the plans either, but I’ve never been all that good at sticking to plans, as I mentioned before, so as I went along and as I’d made all the necessary arrangements for a little bit of extra fuel, I decided we would battle on over the last 500 miles and see if we could get to the Pole and we duly did. But I would say, in general, I’ve been very fortunate. People on the whole have viewed my activities, I think, in a very kindly fashion and I really haven’t had to put up with much unpleasant criticism.

Have there been instances of constructive criticism in your life that have really helped?

Sir Edmund Hillary: Far too many incidents of constructive criticism! I’m actually the impossible person to go on a talk-back show, because people just call in and compliment me on all the things I’ve been involved in. I rarely get a good controversial question. I rather enjoy good controversial questions. A lot of this is the image that I mentioned. Being built up by the media, I think, has created me into sort of a person that really I’m not quite like at all.

You say you like controversial questions.

Sir Edmund Hillary: I don’t like argument, but I enjoy controversial questions that I have to think about, and which I may agree or may not agree with. But I like having to put some thought into answering a question. In other words, a question that stretches my mind a little bit, rather than saying, “Thank you very much for saying those kind words.”

It’s sort of like a different context for a challenge. You’re always up for a challenge.

Sir Edmund Hillary: Yeah, but I don’t like argument, and I’d much rather discuss things in a reasonably quiet and rational way than to have a ferocious argument. In fact, I don’t get involved in ferocious arguments.

What do you see as the challenges now for mountain climbers?

Sir Edmund Hillary: I think that the whole attitude of mountaineers has, in many ways, been forced to change. Most of the big mountains have been climbed, the summits have been reached. The Poles have been reached. People have been down to the depths of the ocean. All the grand things have been largely done. So the really good explorer today, gets his challenges by doing things in different ways. He will climb a mountain by a much more difficult route. He’ll do a face climb, which may be steeper and more dangerous. He’s got the technical equipment and the technique to carry out these things very effectively. Things that we simply didn’t have 40 years ago. I think a lot of the big challenges nowadays, unless you’re going out into space or something like that, are doing things in a more difficult way, by a more difficult route, and in a more difficult fashion. So the modern explorer with his greater technical ability and better equipment is able to do harder challenges and, as a consequence, he gets the same satisfaction out of that as we did 40 years ago with less effective equipment doing more modest achievements. It’s not really what you’ve done, but it’s the sort of challenge it has been for you with your degree of ability and equipment and what you’re trying to overcome.

Are those the important qualities, then, for achievement that you would say are important in anything one might aspire towards?

Sir Edmund Hillary: Yes. If I’m selecting a group, the first thing one has to look for is a record of achievement. It may be modest achievement, but people have shown that they can persist, they can carry out objectives and get to a final solution. If they can do that on small things, there’s a very good chance that they’ll perform well on big things at the same time. Then, I’m a great believer in a really good sense of humor. If you have someone in an expedition who’s reasonably competent and has a great sense of humor, they’re a very stimulating factor for the whole team, and they play a very important psychological part, I think in the success of the team.

You can be involved in a very serious pursuit and have humor about it.

Sir Edmund Hillary: I personally wouldn’t be, if I could possibly help it, involved in a serious pursuit in which there weren’t a few people who could laugh a bit about it. Because I can remember many occasions — maybe we’ve been stuck in a tent or we’re up on the side of a mountain, this heavy snow, avalanches all around us, and we can’t get up and we can’t get down, but we just sat in the tent and reminisced about occasions and days gone by and laughed about old jokes and all the rest of it. Then you really have a very good time, even though you’re sort of poised there between disaster both up and down. People who can make you laugh under those circumstances are very valuable indeed in an expedition.

You seem to have worked out some kind of balance, so that at different times in your life there’s been more personal life, and sometimes more commitment to climbing and doing other things. How did you manage to not go overboard in one direction or another and not give up something that you really cared about?

Sir Edmund Hillary: In the first 33 years of my life which is up until I climbed Everest, I was a very restless and slightly unhappy sort of person. I really didn’t have a great deal of social life, but I’d become very interested in adventurous activities. Perhaps, I was, in some respects something of a loner. But after I got married, that certainly changed my life very considerably, indeed. I found that it was possible to mix having a family with continuing on with adventurous activities, but I think a great deal of that was having a suitable wife. My wife was very, long-suffering. She knew that there were certain things I wanted to do and she was happy that I should do them. She was prepared to put up with considerable periods of being alone with the kids. She, was marvelous, so it made it possible for me to do the things that I wanted to do as well. When I was home, we had a very relaxed and pleasant family life.

Those years from 1953 to 1975 were extremely happy years for me. I did many adventurous activities. I got deeply involved in these aid programs for the people of the Himalayas. I had a nice family, we took our family into the out-of-doors, we camped and we swam and we clambered around the hills. For me, it was a very full and a very happy existence. Well, then of course, came the disaster in 1975, when my wife and my youngest daughter were flying into the Nepal hills where I was building a hospital and their plane crashed and they were killed. And this certainly, for me, was an absolute disaster, really because the two people that meant most to me in life had been killed in one fell swoop. It did take me quite a number of years to get over it. I found the only way to deal with it was to carry on very energetically, doing the things that we had all been doing together, which was largely building schools and things for the mountain people. Although, people used to say to me, “Time is the great healer,” certainly for the first two years I simply didn’t accept this. But, time was a great healer and after the years passed, the memories still remain. But, I think quite a lot of the pain tends to fade a little bit, and life did become a little bit easier. And then, of course, some years later, my wife and I had been very close friends with another couple. Peter had gone with me to the South Pole and been with me in the Himalayas, and his wife June and my wife Louise are very close friends and had been for years and years. Peter died in a plane crash. This was a plane crash in the Antarctic. June and I, who had been close friends for years and years, decided it wouldn’t be a bad idea if we were both alone, so we got married. Over the last six or seven years, that has been a very happy arrangement and, in a sense, a new stage in my life has developed. I firmly believe that companionship, and good companionship, is one of the most valuable things that you can have, and we have certainly had that.

Speaking of companionship, let’s get back to when you were young and you were a loner. Were you unhappy being alone?

Sir Edmund Hillary: I was extremely restless, and being restless can be a slightly unhappy sort of existence, even though it often stimulated me into getting involved in energetic activities. I don’t think I ever was, certainly never was a happy teenager. I think being a teenager’s the worst period in anybody’s life having observed myself and even my children. It’s an important period in anybody’s life, but so many teenagers are so uncertain and so miserable. Sort of trying to feel their way and all the rest of it. There are some teenagers, however who thoroughly enjoy it, but I have no desire whatsoever, if I was given the opportunity to go back to being a teenager, heavens alive, I would dodge it like fury.

What would you say to a young person who felt lonely and asked you, “How am I going to survive this?”

Sir Edmund Hillary: I do think that friends are very valuable to have and particularly good, older friends. If you are even a beginner in some sort of interesting and adventurous activity, quite often, you simply don’t want to think about or be involved with older people and you just want to do your own thing and be with younger people.

But, I recommend to younger people that it’s foolish to start from scratch again. Older people really have a lot of experience. They have a lot of knowledge. Some of them are even quite pleasant people, and I recommend to the young ones to take advantage of all that previous experience and knowledge and understanding which older people have. Absorb it all, and then drop the old people if you’d like, and go off and do your own thing. At least you’re starting with all that built-up accumulation of knowledge and understanding that’s been going on for generations. I think this is a very valuable thing that young people can do. Quite often a young person who is unhappy and uncertain, can make friendships with some slightly older people with more experience and maybe learn a little bit from them and get a little bit more certain in themselves. Now I know a lot of youngsters couldn’t care less about this, but that’s what I would recommend to a lot of them. I actually learned a lot from older people when I was in my 20s. What little I did learn was mostly from older people, not from young ones.

Did you have the feeling you were destined to achieve something very unique and special?

Sir Edmund Hillary: No. I had no such ideas whatsoever. All I wanted was to get out there and do things and have excitement in the adventure sense. I had no conception whatsoever as to what it was ultimately going to be and to what stage I was going to reach.

Where do you think this intense motivation came from? Your mother? A teacher?

Sir Edmund Hillary: I really honestly don’t know. I have no idea. I had a grandmother who was an Irish grandmother who came out to New Zealand and she was a wonderful old lady. She lived up to 96 years old and, even in her 90s, she had great vitality and great enthusiasm and a tremendous sense of fun. I know that for a while I was quite influenced by her spirit she showed during the latter days of her life. But, I really have no idea why I wanted to keep dashing on in these ways because I realized that it wasn’t the normal attitude of the majority of young people. Most young people were more interested in going to the movies or going to the beach or something or other. I really wasn’t all that great on that sort of stuff. I just wanted to get out in the hills.

You said you read a lot. Can you remember some of the books that were most important to you?

Sir Edmund Hillary: Well my memory for names is absolutely appalling, but I know I did pass through a phase of books like King Solomon’s Mines. H. Rider Haggard was the author, and he wrote these great romantic adventure stories. I used to enjoy Georgette Heyer, in which the hero was usually a rather middle-aged gentleman, a very good sword fighter, with a beautiful young lady and all the rest of it. Great sword fighting and all highly romantic, adventurous activity. I used to find these things quite entertaining. I even passed through a phase when I quite enjoyed Western stories. Nowadays, I find them a little on the naive side but, for a period, I found the Western stories quite entertaining light reading. They are very romanticized, as we all know. Later on, I became much more interested in reading biographies, particularly about people who had made their mark in the community. I still enjoy reading books of that nature. I read so many mountaineering books that it’s rather put me off reading mountaineering books now. But I read dozens and dozens of books by explorers like Shipton and Smythe and the Antarctic explorers.

It was called, The Worst Journey in the World and it was largely about a trip taken on Scott’s expedition when they traveled across an area called the Windless Bight, which has very cold temperatures and deep soft snow. They went out to Cape Crozier during the dark, winter darkness to examine the Emperor penguin colony down there. It was a fantastic story. When I went down to the Antarctic, I had rather simple farm tractors. We re-did this journey, but we didn’t do it during the complete darkness. We did it just as darkness was approaching. We did it in our old tractors and we struggled across the Windless Bight and we had very cold temperatures. We were looking for the actual camp that these men had established during the darkness, a most astonishing feat, really. We clambered in our vehicles up on the side of the Cape Crozier peninsula and then we searched around for this old camp which had been established many, many years before. We were unsuccessful and I remember returning back into our tents. I was with Peter Mulgrew and I got out the book, Worst Journey in the World and I read through again, carefully, the pages about when they established their actual camp. I decided that we’d been looking in the wrong direction and Peter also decided we had been looking in the wrong direction, but we disagreed as to which direction it was. So we put on all of our warm gear again and we crawled out of the tent, I headed off in one direction and Peter headed off in the other. It was almost darkness now. Well I happened to be going in the right direction and stumbled down on a low ridge going out across the great ice shelf and I suddenly ahead of me saw a rock wall, obviously made by human beings. And inside the rock wall there were all sorts of bits and pieces of scientific equipment they’d left behind. As a matter of fact, there were literally hundreds of test tubes that had been left there and pieces of clothing and old skis and things of that nature. That really was one of the most exciting moments that I can remember. I called out to everybody at the camp and we all came over. To look on this thoroughly miserable, terrible campsite, where these people had spent several weeks in complete darkness, carrying out their scientific research, it really was an amazing experience. In that sense, I relived, although to a lesser degree, what these heroic figures in that book, The Worst Journey in the World, had described so well.

Good thing you brought the book along.

Sir Edmund Hillary: It was our bible, so we had it with us.

I know you’ve written an autobiography. What do you think would be the most valuable thing young people might get out of reading it?

Sir Edmund Hillary: My autobiography was just a narrative, as well as I could produce it, of what had happened to me and what I’d thought and what I had carried out. I think it’s probably the best book I have produced, although I don’t necessarily say that makes it one of the great books of all time. I would like to think anyway that it would indicate to people that you don’t have to be a genius or an exceptional person to take part in interesting activities and to ultimately be successful in them.

Maybe it’s an exceptional person that can instill in a young person the idea that motivation or the desire to achieve is very important.

Sir Edmund Hillary: I’ve never really thought in that particular way. Most of the exceptional people I know are people who have had the mental ability and the physical ability to perform to a high degree of excellence, and I certainly was never in that class. I think as far as determination and motivation was concerned, I was reasonably competent, but I was certainly not a great athlete.

What advice would you give a young person striving to achieve?

Sir Edmund Hillary: I would advise them to aim high. To set their sights at a pretty tough target and don’t be too worried if you’re not successful at first. Just keep persisting and keep improving your standards, getting better and better and ultimately, you’ve got a pretty fair chance at achieving your desired goal. I am not one of those people who believe, for instance, that every American could, if they so wish, become President of the United States. I mean, there’s a limited number of Presidents of the United States and, obviously, only a few are going to achieve that. But, I do think that virtually everybody that’s born has the ability to be very competent at doing something. I think that, in itself, is worthy of aiming towards, just to be competent at doing anything you particularly wish to do.

As far as adventure goes, what do you think some of the big challenges of this next century are going to be?

Sir Edmund Hillary: I think most of our major challenges are not going to be in the physical field at all. I think they’re going to be in the field of human relations, of getting on with each other, of contributing. People accepting that they have to contribute something, their thoughts, their ideas, maybe even their money, towards producing a world society that is perhaps a little bit more honest and reasonable than it is now.

What would you say to a young person that would encourage them to be involved in such activities, and yet, would satisfy their craving for adventure?

Sir Edmund Hillary: I don’t normally preach to young people anyway. Not unless they ask me a question. Even with my kids, I never tried to tell them what they ought to do. I think my wife and I tried to build up in them a love of the outdoors. They enjoyed camping and swimming and canoeing and those types of activities. But as for actually trying to tell them how they should organize their lives and what philosophies they should have, it’s for them to discover for themselves. I think it’s very hard indeed to impart to a young person what you think they should do.

Do you do a lot of introspection?

Sir Edmund Hillary: I probably used to. I do a lot of thinking. I don’t know if that’s introspection. I think about the past, I think more about the future. I think about jobs still to be done and I sometimes wish I knew some of the answers to the problems which seem to plague humanity. I think a lot about people and about our environment. There are so many things that are difficult to understand and to overcome, that finding answers for them is not always easy at all. But I suppose if everything was easy, life would be exceptionally boring.

You’re a man who always has some goal or another. How many do you have going right now? What do you want to achieve?

Sir Edmund Hillary: As I’ve gotten older, my goals have become more solidified. My main concentration is on the welfare of the people I’ve worked with in the Himalayas and on human welfare in general. I’m also extremely interested in the environment and trying to encourage people to be more concerned about what we’re doing to our world. Now I’m just one of thousands and thousands of people who have these same views these days. I think this is one of the great steps forward we’ve seen in modern decades — the considerable growing interest that people have in the environment and in keeping it reasonably clean and wholesome. I certainly hope it remains that way.

You see the whole world as full of challenges. What would you say to a young person who says, “Everything’s been done”?

Sir Edmund Hillary: I don’t think that everything’s been done by any means. There are so many young people today who haven’t got their due who see constant challenges in every direction and are doing exciting and adventurous things. The main thing about challenges is that they don’t just pop into your lap. You have to have your eyes open, you have to be alert. Otherwise, a challenge may well pass you by and you won’t see it at all.

So I think if you are ready for challenges, if you’re physically fit and you feel you’re well trained and your interests have been turned in the right direction and your eyes are open, you’ll see challenges. There are challenges all over the place.

One more question. In your autobiography, you said you hoped that there would be room in space exploration for a different type of man. “Perhaps more like me: resourceful, enthusiastic and even a little irresponsible.” What did you mean by that?

Sir Edmund Hillary: Our heroes in space are remarkably competent and well-trained people, but I don’t think they’re encouraged to be individualistic. They are extremely competent in set routines and they have great ability to carry out these highly technical things and they display great courage and determination in the process. But they are highly trained technicians in their particular field. I just think that maybe there’s some place in the future for people who are pretty good at improvising. I think I’m quite good at improvising, actually and I think there are a lot of people around who are not extremely good technicians but are quite good at improvising. I think many businessmen for instance, may not have extremely good university degrees on business administration, but they’re exceptionally good at improvising and carrying things through to a successful conclusion. I think, in all aspects of life, the improviser, the person with imagination and perhaps not quite so much technical skill, there is still a place for them. I always think that the bush pilots up in the far north, of course, are very, very competent with their aircraft, but they have great ability to improvise, to land in all sorts of strange places and to do rather daring things very successfully. That’s really the sort of thing I was referring to. People who are pretty competent, but not utterly expert, but with the ability to adapt to all sorts of conditions. I have met a number of the astronauts, and some of them seem to me people who are extremely competent, but almost brainwashed into a routine that enables them to respond according to the book, very effectively.

What I’m hearing you say is that the human ability to have spontaneity and originality and creativity is the element that you must add to the knowledge.

Sir Edmund Hillary: Right. To the skills and so on.

Well, Sir Edmund, thank you so much for speaking with us today. It’s been an honor.

All right.