I went into repertory for nine years and learned how to be an actor in order to become the best possible actor I could become. Not the best possible actor, because there’ll always be, whatever you do, people who are better or worse at what you do.

The actor the world knows as Michael Caine was born Maurice Micklewhite, Jr. in London, England. His father worked as a porter in the fish market; his mother was a cook and cleaning woman. Young Maurice lived with his parents and a younger brother in the London Borough of Southwark, on the south side of the River Thames. The Micklewhites were a close and loving family but material comforts were few; the cramped old buildings where working-class families like the Micklewhites lived in the 1930s lacked indoor plumbing, and opportunities for advancement in pre-war Britain were remote. Early in Maurice’s life, the discomforts of poverty were joined by the terrors of war. Young Maurice was six years old when Britain entered World War II. The elder Micklewhite was immediately called up for military service and Maurice would not see his father again for six years.

Without their father, Maurice and his three-year-old brother were forced to assume responsibility for supporting their mother emotionally through trying times. When the Germans began the nightly bombing of London, Maurice was sent to live with another family away from the city. Maurice and another boy were grossly neglected by the host family, who left town for days at a time, leaving the boys locked in a cupboard until they returned. When Mrs. Micklewhite discovered the condition her son was being kept in, she relocated him to another shelter, but the experience left Maurice profoundly claustrophobic.

With the end of the war, the Micklewhites were reunited. Because their old home had been severely damaged in the bombing, the family moved into new prefabricated housing in the South London neighborhood known as Elephant and Castle. The new housing was regarded as substandard by middle-class Britons, but to the Micklewhites, it was a step up, with indoor plumbing and a small garden. Their home remained a haven, but the streets outside were dangerous, with young men forming rival gangs for protection.

Maurice found safety at the neighborhood youth club. He originally joined to play basketball but was soon drawn to the club’s drama classes and the girls who gathered there. Once inside, he fell in love with acting and the theater.

He acted in plays at the youth club and began to dream of a career in the theater. Film actors like Cary Grant and Humphrey Bogart further stimulated his imagination, and, upon leaving grammar school at age 16, Maurice went to work as a file clerk and messenger for film companies around London. He did not imagine that a working-class boy from “the Elephant” could ever become a film star himself, but he hoped to find some way to pursue an acting career and make a life in the theater.

Real life intervened violently when he was called up for national service at age 19 and sent to Korea, where the United Kingdom had joined the United States and other allied forces in a seemingly interminable conflict. The young infantryman resigned himself to certain death when his unit encountered massively superior Chinese Communist forces. Surviving this experience, Maurice resolved to make the most of his life in the years ahead.

Returning to England and civilian life, he set out to pursue his dreams of the theater. Jaundiced and emaciated from malaria contracted in Korea, with no theater training and an unmistakable cockney accent, he knew he faced formidable obstacles, but Maurice decided he would set aside any ambition other than becoming the best actor he could possibly be. He answered an ad for an assistant stage manager at the Westminster Repertory Company in Horsham, Sussex, and was soon playing small walk-on roles.

Then, as now, provincial repertory theaters were the great training ground of British actors, and Maurice Micklewhite, now acting under the name Michael White, learned his craft gradually. From Horsham, he moved to the Lowestoft Repertory Company in Suffolk, where he met his first wife, Patricia Haines. They married in 1955 and would have one daughter, Dominique.

In repertory, the journeyman actor played a variety of roles and learned to assume the accents of all regions and classes in the United Kingdom. The British actors’ union, Equity, already had a Michael White on its rolls, so when his agent asked him to provide a new name in a hurry, he grabbed the name Caine from a nearby marquee on a movie theater showing the film The Caine Mutiny. Maurice Micklewhite was now Michael Caine.

For nearly ten years, Caine labored in provincial repertory and in small roles — sometimes uncredited — on film and television. His marriage to Patricia Haines ended, and at age 30, Michael Caine was still struggling, while contemporaries like Sean Connery, Albert Finney, and Peter O’Toole were starring on the West End and in Hollywood films.

Caine had played the role of a soldier in the 1956 film A Hill in Korea, and one of the stars of that film, Stanley Baker, introduced him to Cy Endfield, the American director of Baker’s new film, Zulu. After seeing the actor in a play on the West End, Endfield cast Caine against type as an upper-class officer in the taut drama of a besieged British Army unit in 19th-century South Africa. Zulu was one of the international hits of 1964, and Michael Caine’s performance did not go unnoticed. Harry Saltzman, producer of the popular James Bond films, signed Caine to play an unconventional hero in the espionage film The Ipcress File. Unlike the tuxedo-clad superman of the Bond films, Caine’s Harry Palmer character was a spy-as-everyman, with a cockney accent, a beige raincoat and a pair of eyeglasses with thick dark frames. Studio executives in Hollywood were skeptical that the public would accept such a mundane hero, but British filmgoers responded easily to Caine’s unpretentious charm, and working-class Londoners, in particular, were thrilled to hear their own voice coming from the screen in the role of a hero, rather than that of a servant or comedian.

Michael Caine was now a star in Britain, but even greater fame was soon to come. The postwar flowering of British popular culture had captured the imagination of a public far beyond the British Isles. British playwrights like John Osborne and Harold Pinter, musicians like the Beatles, and actors like Connery, O’Toole, and Finney had helped create a worldwide interest in British drama, music, film, and fashion. Michael Caine was set to ride the crest of this wave.

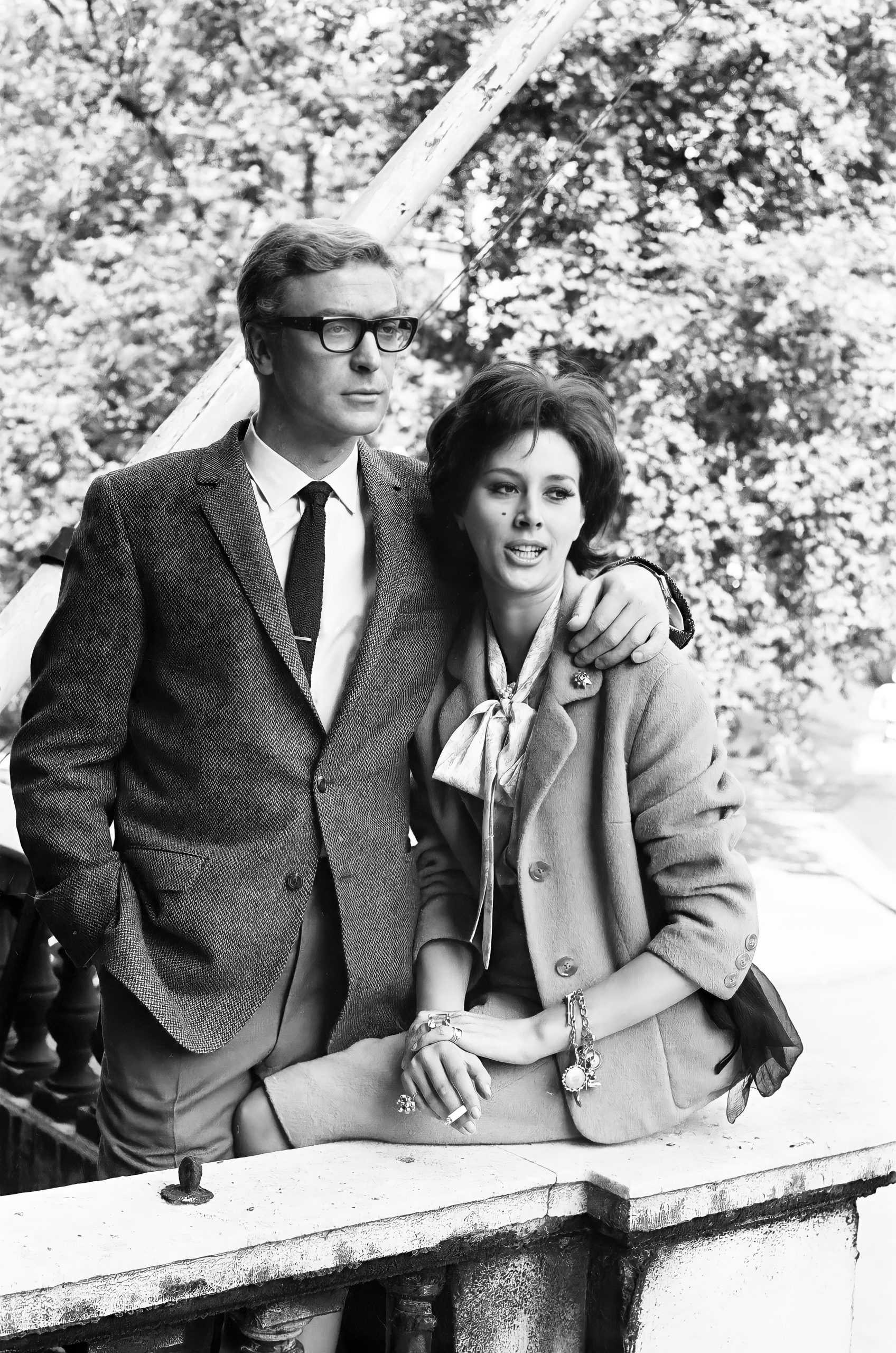

Caine’s former flatmate, actor Terence Stamp, had enjoyed good reviews in the play Alfie on Broadway but declined an offer to appear in the film version, and the producer gave the role to Caine. The role of Alfie, an amoral cockney womanizer, was a good fit for Caine, who made it entirely his own. Addressing the camera directly in a series of disarmingly blunt observations on male-female relations, Caine the actor managed to charm the audience even as they were appalled by the behavior of Alfie the character. The film was a massive international success. Caine, now a star on both sides of the Atlantic, was nominated for an Oscar as Best Actor.

The American film star Shirley MacLaine invited him to Hollywood to appear with her in the unconventional thriller Gambit, and Michael Caine received his first taste of life in Hollywood, meeting screen heroes like John Wayne and Cary Grant. Back in Britain, Caine reprised his role as Harry Palmer in the films A Funeral in Berlin and Billion Dollar Brain. Caine’s career was riding high, with memorable leading roles in the crime caper movie The Italian Job and the Newcastle-set gangster film Get Carter. Caine worked with an old idol, stage and screen legend Laurence Olivier in the intimate thriller Sleuth (1972), with Caine displaying his versatility through a series of startling plot twists.

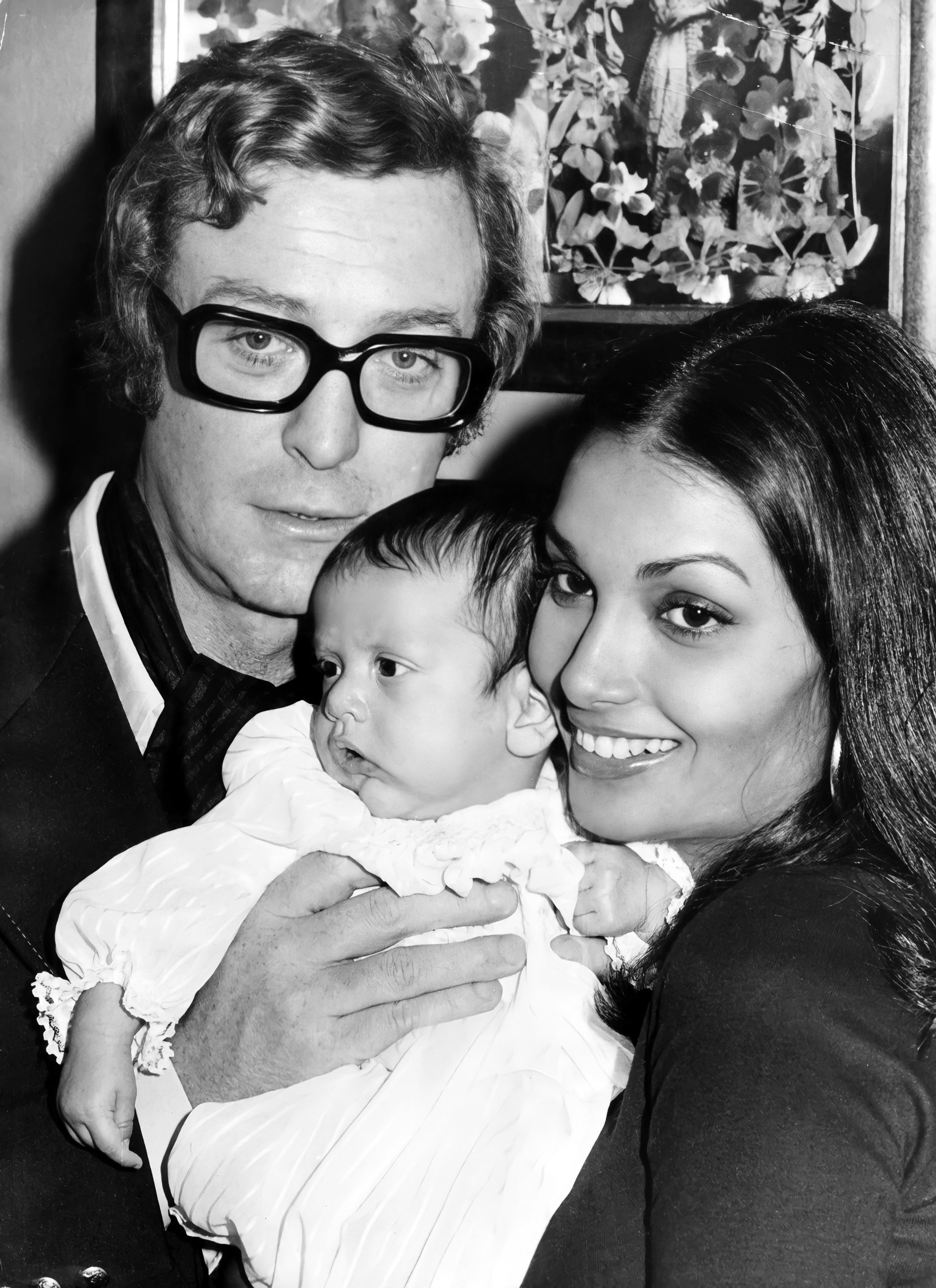

Caine enjoyed a notably lively bachelor life in the discotheques of London until he met actress and model Shakira Baksh. He claims he fell in love with her when he saw her in a coffee commercial on television. Baksh, born in Guyana to a family with roots in Kashmir, was not initially interested in meeting Caine, and he claims he called her for ten days in a row before she agreed to go on a date with him. Once they met in person, a romance developed quickly and they were married in 1973. Caine was reunited with an old acquaintance from London theater days, Sean Connery, in the 1975 adventure spectacle The Man Who Would Be King, directed by Hollywood legend John Huston. Shakira Caine played the part of a Himalayan princess in the film.

Over the years, Caine appeared as military men in a number of big-budget World War II films, including The Battle of Britain, The Eagle Has Landed and A Bridge Too Far. In the late 1970s, new British tax laws called for an 82-percent marginal tax rate on higher incomes. Michael and Shakira Caine moved to California, making their home for the next ten years in Beverly Hills, where they raised their daughter, Natasha.

Caine’s second Hollywood effort, The Swarm, was a failure, despite an all-star American cast, but Caine took the advice of fellow Briton James Mason, who enjoyed a lucrative film career long after his leading-man days were over. Mason advised him to keep working and not to stay off the screen too long, waiting for the right role, but to take the best role on offer. Caine appeared in a number of undistinguished American films in this period, including Beyond the Poseidon Adventure, but he enjoyed some success in the Neil Simon comedy California Suite and the thrillers Dressed to Kill and Deathtrap.

A change of government — and tax laws — brought Caine back to Britain in the ‘80s, and he inaugurated a career resurgence with the comedy Educating Rita and the underworld story Mona Lisa. An uncharacteristic role as a guilt-ridden philandering husband in Woody Allen’s Hannah and Her Sisters (1986) won Caine renewed critical acclaim and an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor. He did not attend the Oscar ceremony in Los Angeles, as he was filming Jaws: the Revenge in the Bahamas. Caine achieved unexpected success and won a new generation of fans with his appearance as Scrooge in The Muppet Christmas Carol in 1992. He had considered retiring from the screen when his friend Jack Nicholson lured him back for the 1996 film Blood and Wine.

Caine took on one of the best roles of his career, the kindly doctor in Depression-era New England, in the 1999 film of John Irving’s novel The Cider House Rules. He received glowing reviews for the role and was awarded his second Oscar as Best Supporting Actor. In the year 2000, he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II for his services to British film. In memory of his father, he accepted the honor as Sir Maurice Micklewhite, although the public continued to recognize him as Sir Michael Caine.

Although he was nominated again for his performance in the 2002 film version of Graham Greene’s The Quiet American, Sir Michael planned to retire from the screen for a second time. An unexpected third act in his career began when director Christopher Nolan offered him the role of the butler Alfred in Batman Begins. Nolan’s conception of the familiar characters of the Batman franchise greatly enlarged the role of Alfred. In Nolan’s vision, Alfred is a family retainer who has virtually raised the orphaned Bruce Wayne from childhood, preparing him to become Batman. The 2005 film was a worldwide blockbuster, and Caine’s performance was recognized as an essential part of the film’s success. Caine reprised the role of Alfred in The Dark Knight and The Dark Knight Rises. He worked with director Nolan again in the films Inception and Interstellar. In 2009, Caine gave one of the most intense performances of his career in Harry Brown, playing a retired Royal Marine who takes the law into his own hands to bring justice to his deteriorating inner-city neighborhood.

Michael Caine has published a book-length essay on Acting in Film; two books of trivia, Not Many People Know That and Not Many People Know This Either; and three volumes of memoirs, What’s It All About?, The Elephant to Hollywood, and Blowing the Bloody Doors Off. He and his wife, Shakira, remain together, after more than 45 years of marriage, and have homes in London and in Leatherhead, Surrey.

In more than 150 feature films, Michael Caine has brought intelligence and humanity to roles as varied as the hunted gangster in Get Carter; an alcoholic teacher in Educating Rita; men at war in The Battle of Britain and A Bridge Too Far; a soldier of fortune in The Man Who Would Be King; and the loyal butler Alfred in The Dark Knight trilogy.

Born in London to working-class parents, he served in the Korean War and struggled for a decade to build his career as an actor before first winning notice in the historical drama Zulu and the spy thriller The Ipcress File. In 1966, his performance as the cockney playboy Alfie rocketed him to international stardom.

Michael Caine has been nominated for an Oscar in five consecutive decades, winning for his roles as a guilt-ridden philandering husband in Hannah and Her Sisters (1986) and as a kindly doctor in The Cider House Rules (1999). His films have made over $7.8 billion worldwide, placing him among the top-grossing film stars of all time. In 2000, he was knighted by HM Queen Elizabeth II for his contributions to world cinema.

You’ve said that you began your career without any expectations of becoming a star. Why was that?

Michael Caine: I was in Korea, in the war in Korea, and there’s an incubation period for malaria, and I came home, and then I collapsed with malaria. And so there I was, I’m very, very thin — I lost a lot of weight — a slightly yellow complexion and the thick cockney accent, and I knew I would never be rich or famous. You absolutely knew that.

So I went into repertory for nine years and learned how to be an actor in order to become the best possible actor I could become. Not the best possible actor, because there’ll always be, whatever you do, people who are better or worse at what you do. I just started to be the best possible actor I could be, and that was the end of that.

I think it just came from knowing that I was never going to be like Laurence Olivier or people like that, or John Gielgud — great theater actors — or big movie stars like Cary Grant and Robert Taylor, and John Mills in England, and people like that. But I just decided to make myself the best that I could possibly make myself without any reference to anyone else.

Apart from the damage to your health, what impact do you think your service in the Korean War had on you?

Michael Caine: To me, I was always disgusted by war. It’s always started by men who are too old to go; that’s the start. And then they send the young men, who are too stupid to know what they’re getting into, like me. And then you wind up in Korea with the American Marines, which is not a very good idea. And no, I mean it’s the most terrifying ordeal that you can think of, and you have to do things that you would never think of doing. But there was one great advantage to me from the war, which was that…

Michael Caine: We got into a situation, on a patrol, where we were surrounded by Chinese, and we knew we were going to die, but what you worry about when you get into that situation — are you going to be a coward, are you going to be yellow and run, you know, and there were only four of us, a little tiny patrol. And we all said, “Well, we’re going to make this as expensive as we possibly can, our deaths.” And we were going to do that. And the officer said, “Let’s go towards their lines and go right round.” So we went back. They were waiting for us to go back to our lines, and then we went back to the Chinese line and went right the way around them and back, and so we survived it; we didn’t have to do that. But I came out of it knowing that I wasn’t a coward, and I’ve known that for the rest of my life. So for all the things I hated about Korea and the things I hate about war, which I do hate, I came out of it with one advantage, which fostered one of my pet phrases, which is “Use the difficulty,” and that’s how I used that difficulty.

You’ve described acting as “not acting,” or as “listening and reacting.” What do you mean?

When I was a young actor in repertory, I came — very young — and I came on rehearsals, and I was playing a drunk — a drunken man. And I came on, and then the producer said, “Just a minute, Michael, what are you doing?” I said, “I’m drunk in this scene.” He said, “I know you’re drunk in this scene. What are you doing?” I said, “I’m playing a drunk.” He said, “No, you’re not. You’re playing an actor.”

I said, “What are you talking about?” He said, “A drunk is a man who is trying to speak properly and walk straight. You’re an actor who is trying to speak in a mumbled voice and walk crooked.” And there, he described movie acting to me in one sentence — and the same thing he did when I had a crying scene. He said, “What are you doing?” I said, “I’m crying. Blah, blah, blah.” And he said, “No. When a man cries, it’s the last thing he wants to do.”

He said, “He will do anything but cry. He will stop himself crying no matter how tragic it is. And he would do everything, and only when he’s completely defeated emotionally will he start to cry properly.” He said, “He will do anything but cry — a real man.” He said, “You are an actor who is trying to cry.” And he described, again, movie acting. That’s a complete description of movie acting.

The hardest thing that I’ve had to do on camera was in Harry Brown, crying. And I had to do that, and I did that. If you saw a movie I did called Harry Brown, you’d see me cry, and you’d see the man doing that, doing everything but cry and then having to break down because he was so unhappy.

You’ve had some extraordinary luck in your career. You were in a very interesting place in a very interesting time, the British theater and film scene in the late ‘50s and the ‘60s. So many of the people you knew and worked with in the early days went on to great careers, too.

Michael Caine: What it was, in those days, everybody I knew was not famous, and nobody I knew didn’t become famous. It’s like — I had this friend called David Baron, who was an actor. And he said to me, he said, “I’m going to write a play, and you’re going to be in it.” I said, “All right, David,” you know.

He said, “I’m fed up with this. I’m going to be a playwright,” he said. But he said, “David Baron’s not my real name. I’m going to write under my real name.” I said, “What’s your real name, David?” He said, “Harold Pinter.” I was in his first play, at the Royal Court, called The Room. And you meet people like that.

And the other one, the other actor I was with was John Osborne. He said, “I’m going to write a play,” and he said, “I’ve nearly finished it.” I said, “What’s it called?” He said, “Look Back in Anger.” I went, “Oh, great. Lovely.” You know. It was time after time that you met people, that they just — everyone I knew. Peter O’Toole, he was in the play; he became a movie star. I was his understudy. He became a massive star, you know. Albert Finney, Tom Courtenay, they all became stars, and these were guys I knew. Terence Stamp, he became a star. I shared a flat with him. So it was one of those eras like that, where everybody became someone.

I came along at a time when social life in England was changing, and people were starting to write about working-class people. Movies were starting to be made about them. My first job, when I came to London, I was an understudy for Peter O’Toole, who was in a play, and he became a star in the play — a fabulous actor. And he became the star in this play called The Long and the Short and the Tall, which is the first British play ever written about private soldiers in the British Army. Like, Bill Naughton wrote Alfie about an ordinary Englishman. John Osborne wrote Look Back in Anger. And they were the first playwrights to write about working-class people in Britain, I promise you.

Society changed when people wrote films about working-class people and working-class people went to see them. Because when I was a young man, when I went to see a war film, I went to see American films because American films — From Here to Eternity and those, The Naked and the Dead — were all about private soldiers. English war films were all about officers, you know. I’d been a soldier; I didn’t want to see a picture about officers.

We know your original name was Maurice Micklewhite. How did you become Michael Caine?

Michael Caine: I came out of a repertory theater in the country, and I came to London, and I didn’t have a telephone, and there was a club called the Artsiana Club — where all the out-of-work actors used to be in the coffee bar in the basement — and it was at Leicester Square, which is like Broadway in New York, all the big cinemas and theaters.

And every night, I used to go and phone my agent — to see if there was a job — at six o’clock, in a phone booth on Leicester Square. And because my name was Micklewhite, I called myself — I didn’t want to use that name — in repertory, I was called Michael White. And then, one night, I got a job, and the woman said — my agent, Josephine, said to me, she said, “You’ve got to change your name because you’ve got to join Equity, the trade union.”

I said, “Yes.” She said, “There is another Michael White in the trade union.” So she said, “You can call yourself ‘Michael,’ but you can’t call yourself ‘White’.” She said, “And I need a name now because I’ve got to call the producer, and I’ve got to say your name and tell him who’s going to play the part.” So she said, “Give me a surname.” So I look around the cinemas, and one of my favorite actors is Humphrey Bogart. And on the Odeon in Leicester Square, at that time, was The Caine Mutiny with Humphrey Bogart. And I said, “Michael Caine.” She said, “Okay, how do you spell it?” I said C-A-I-N-E, that’s it. If I had gone to the Leicester Square Theater, I’d have been “Michael 101 Dalmatians.”

What do you think it was that got you out of the world you were in and brought you to Hollywood and made you one of the most famous people in the world?

Michael Caine: It was just keeping going at what I did. I tried to make myself better every day and eventually, someone noticed it. Namely, Cy Endfield, who was the director of Zulu. He saw me in a play, my first play in the West End, called Next Time I’ll Sing To You. And I played a cockney in that, and he wanted to cast me as a cockney. It was about the military, and I was going to be a cockney corporal.

I went for the audition, and I didn’t have a phone, and he said, “I’m sorry, Michael. We’ve cast the corporal, you know, but I couldn’t call you. You don’t have a phone.” I said, “No, I don’t have a phone.” I said it was okay because I’d been turned down for a lot of parts. I was in a very long bar at the Prince of Wales Theatre in West End in London — a very long bar — and I always regard that long bar as the secret of my success because if it had been shorter, I wouldn’t be here.

If the bar had been shorter, my film career might not have happened because I had got to the door, I was just opening it, and Cy Endfield said, “Come back here,” he said. I was cast as a cockney corporal, and he looked at me, and I was tall, skinny, blonde. He said, “You look more like an officer to me.” He said, “You don’t look like a corporal.” A corporal would be sort of tougher looking. He says, “Can you do a posh accent?” And I said, “Yeah.” I said, “I’ve been in repertory for nine years. I’ve played hundreds of posh people.” And he cast me as the officer in Zulu, which started my career. And the thing about that was — thinking in terms of the British class system — if he had been an Englishman, that director, even if he’d been a left-wing communist, he would not have cast me as an officer, I promise you.

For younger people who are listening and admire all that you’ve done, you’ve often said, “Watch for opportunities.” But sometimes, it’s hard to know what’s an opportunity.

Michael Caine: Sometimes you don’t know when something good is happening. For instance, I played a very posh officer in Zulu. Now, I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life playing posh officers, you know. I don’t have a naturally posh accent, and I’m not a naturally posh officer. It was a performance. But it brought me all the career that I ever had. And I’ve never played a person like that again since, someone as posh as that. I played a lot of posh people, but it was no indication of what I was going to do as an actor, Zulu. But it brought me to attention.

I was having dinner. I was sharing a flat with an actor there called Terence Stamp, and we were having dinner at a restaurant. And Harry Saltzman, one of the producers of the Bond films, is making the film The Ipcress File, and he’d bought the novel from Len Deighton. And he was in this restaurant, and he sent me a message, saying, “At the end of your meal, would you please have a coffee with me?”

He was with his wife and kids, and I went over, and he gave me Ipcress File. He’d just seen Zulu that night. Now Ipcress File was a sort of cockney working-class spy. He had just seen Zulu, with a posh, very posh officer, absolutely nothing to do with the other treatment.

I asked him about that. I said, “Well, you’ve just seen Zulu; now you want me to play the…” He said, “It’s about screen presence, Michael. Once you see the presence, once you’re on screen, you’ve either got screen presence or you haven’t. And there’s absolutely nothing you can do about it.” I didn’t know I had it. I didn’t know what it was, but it seemed that I had it.

Ipcress File made me famous in England. Alfie made me famous in America because I got nominated for an Academy Award the first time, and it was the first movie — they made a lot of British movies, but they never got a release in America. Alfie got released in America, a general release.

And what the difference was between the stars of my generation — like Sean Connery, Richard Burton, Peter O’Toole, Albert Finney — is we all became stars in America. Before that, British movie stars were stars in Britain, not in America. Lots of British actors went to America and became stars. Cary Grant did it, you know. Olivia de Havilland and Joan Fontaine were both English.

You mentioned Sean Connery. You met him early on, didn’t you?

Michael Caine: Sean Connery — what happened with Sean, how Sean got into show business — he was a “Mr.” — I think he was “Mr. Edinburgh.” He was a big weightlifter. And they were doing South Pacific, and there’s a song in it called “There Is Nothing Like a Dame,” sung by all these sailors, you know, big robust sailors. And they only had small chorus boys, and it didn’t look right, them singing this song, “There Is Nothing Like a Dame.”

So they went out and looked for great big, masculine men, and of course, they went to weightlifting places. And they found Sean, and Sean was in the chorus of South Pacific. And they opened on a Thursday, and the Saturday night, there was a party to which I took two girls. And he came after the show, late, about eleven o’clock. And he walked in, and he saw me with two girls. And he walked straight over to me and introduced himself and took one of the girls. So that’s how I met Sean Connery.

The first big famous person I ever met was John Wayne, and he was exactly like I expected him to be. I was staying at the Beverly Hills Hotel, and I was there on my own because I was there to make a movie called Gambit with Shirley MacLaine, but she went over the schedule on what she was doing and didn’t turn up. And so nobody knew me in Hollywood and knew I was there except Shirley MacLaine and the producers and directors of the movie.

They left me in the hotel, and I used to sit in the lobby to look for famous people, film stars. And John Wayne came in one day and signed into the hotel. And then he saw me sitting there, and he said, “What’s your name, kid?” I said, “Michael Caine.” He said, “You in that movie Alfie?” I said, “Yeah.” He said, “You’re going to be a big star, kid.” I said, “Well, thank you, Mr. Wayne.”

He said, “But let me give you some advice.” I said, “What?” He said, “Talk slow. Talk slow and don’t say too much.” I said, “Thank you, sir, thank you very much.” He said — and I had on suede shoes — and he said to me, “And never wear suede shoes.” I said, “What?” He said, “Never wear suede shoes.” I said, “Why not?” He said, “Because remember, I just told you, you’re going to be famous.” He said, “And you’ll be in the toilet taking a pee, and the guy next to you is going to go ‘Michael Caine!’ — and he’s going to pee all over your shoes, so never wear suede shoes.”

Did you listen to his advice?

Michael Caine: Oh yeah, I threw the suede shoes away. Oh, well. He said, “Talk slow; don’t say too much.” I then made 20 pictures where I never stopped talking very quickly. Because he was a cowboy, you see, and cowboys don’t say too much, do they? Because they fall off, otherwise, if they keep talking.

I’ll tell you another thing with cowboys. Richard Widmark told me — I was talking to him; he said, “What’d you say?” He said, “Talk in this ear.” He said, “I’m a bit deaf in that one.” I said, “Oh, I’m sorry. Why is that?” He said, “Well, playing all those cowboy parts.” He said, “Someone’s always shooting a bloody gun, and it goes, and it’s always been in my left ear.” And he said, “You go deaf.” He said, “All actors who play cowboys in America are deaf in one ear.” I said, “What?”