Through reading, I escaped the bad parts of my life in the South Bronx. And, through books, I got to travel the world and the universe. It, to me, was a passport out of my childhood and it remains a way — through the power of words — to change the world.

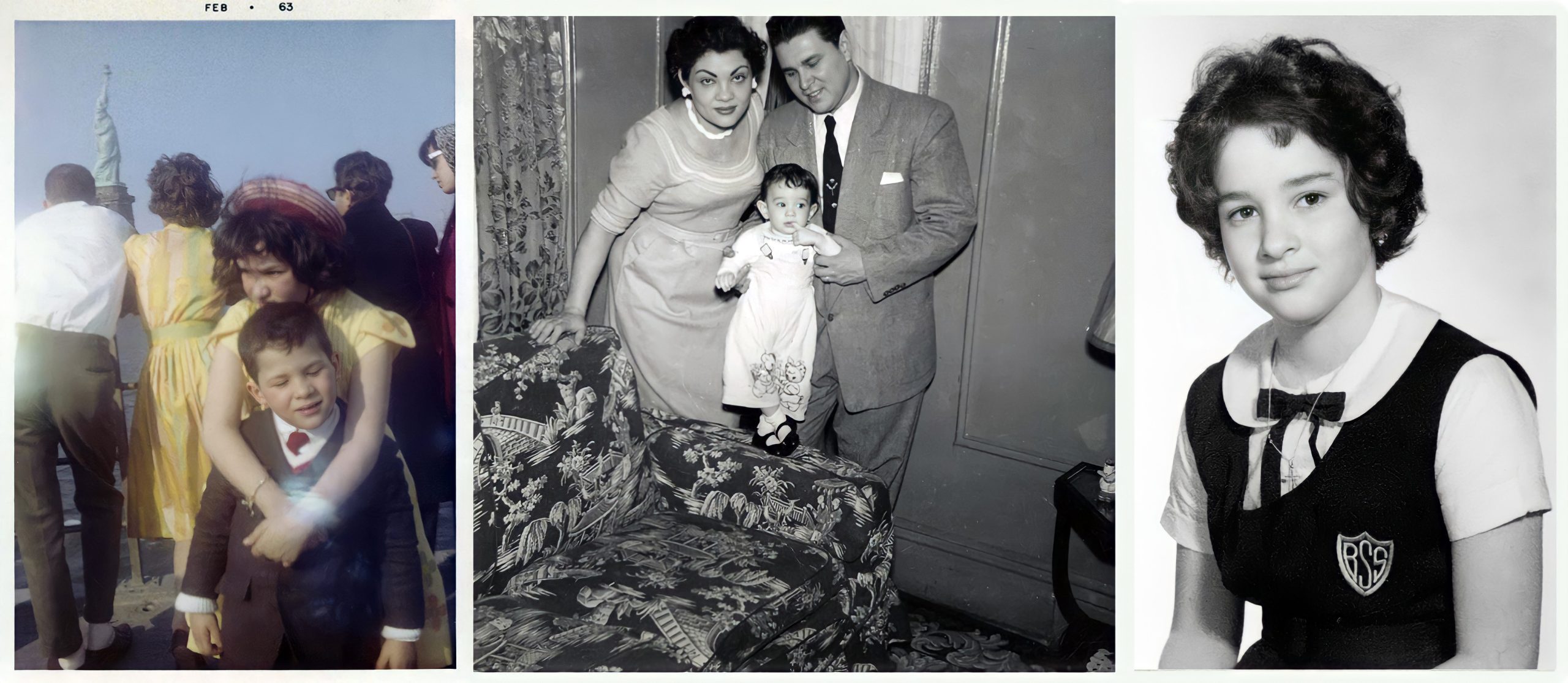

Sonia Maria Sotomayor was born in New York City in the borough of the Bronx, where she spent her formative years. Her parents, Juan and Celina, were both born in Puerto Rico. Juan was a factory worker, Celina a nurse. When Sonia was three, shortly after the birth of her brother, Juan, the family moved from a small apartment in the South Bronx to the Bronxdale Homes, a public housing project. From kindergarten through eighth grade, Sonia Sotomayor attended the Blessed Sacrament Parish School. Life at home was difficult, as strained finances and friction between her parents were aggravated by her father’s worsening alcoholism. Little Sonia found refuge in books and in the home of a loving grandmother who lived nearby. At age seven, Sonia was diagnosed with diabetes. Living with this disease taught her self-reliance; she soon learned to sterilize her own needles and inject herself with insulin.

Conditions in the housing project deteriorated in the 1960s. Crime and gang activity increased in the neighborhood, and drug users discarded their paraphernalia in the hallways and stairwells. When Sonia was nine, her father died of a heart attack, an end hastened by his excessive drinking. The benefit from her father’s life insurance policy enabled Sonia, her mother, and her brother, Juan, to move from the projects to Co-op City, a massive cooperative apartment complex in the Northeast Bronx. After her father’s death, Sonia threw herself into her studies and began to excel academically. Childhood reading of the Nancy Drew mysteries piqued her interest in crime and detection, but the Perry Mason television show, with its dramatic courtroom scenes, inspired her to become an attorney. By age ten, she says, her heart was set on going to college and becoming an attorney.

Sonia was valedictorian of her class at Blessed Sacrament, and at Cardinal Spellman High School, where she was an enthusiastic member of the debate team. When a debate team friend who was a year older won a scholarship to Princeton University, he suggested that Sonia apply as well, and to her surprise she was accepted and awarded a full scholarship.

An Ivy League university in an idyllic small-town setting was an abrupt change for a girl from the Bronx. The university had only recently begun to admit female students, and as a Latina she was doubly exceptional in the student body. The curriculum was challenging, and Sonia Sotomayor soon learned that she would need to improve her writing skills to succeed. She boned up on grammar, read widely over her vacations and worked closely with her thesis advisor. The extra work paid off; she graduated summa cum laude and won the University’s Moses Taylor Pyne Prize, the highest honor Princeton awards its undergraduates. She was offered a scholarship to Yale Law School. In the summer between graduating from Princeton and entering Yale Law School, Sotomayor married her high school boyfriend, Kevin Noonan.

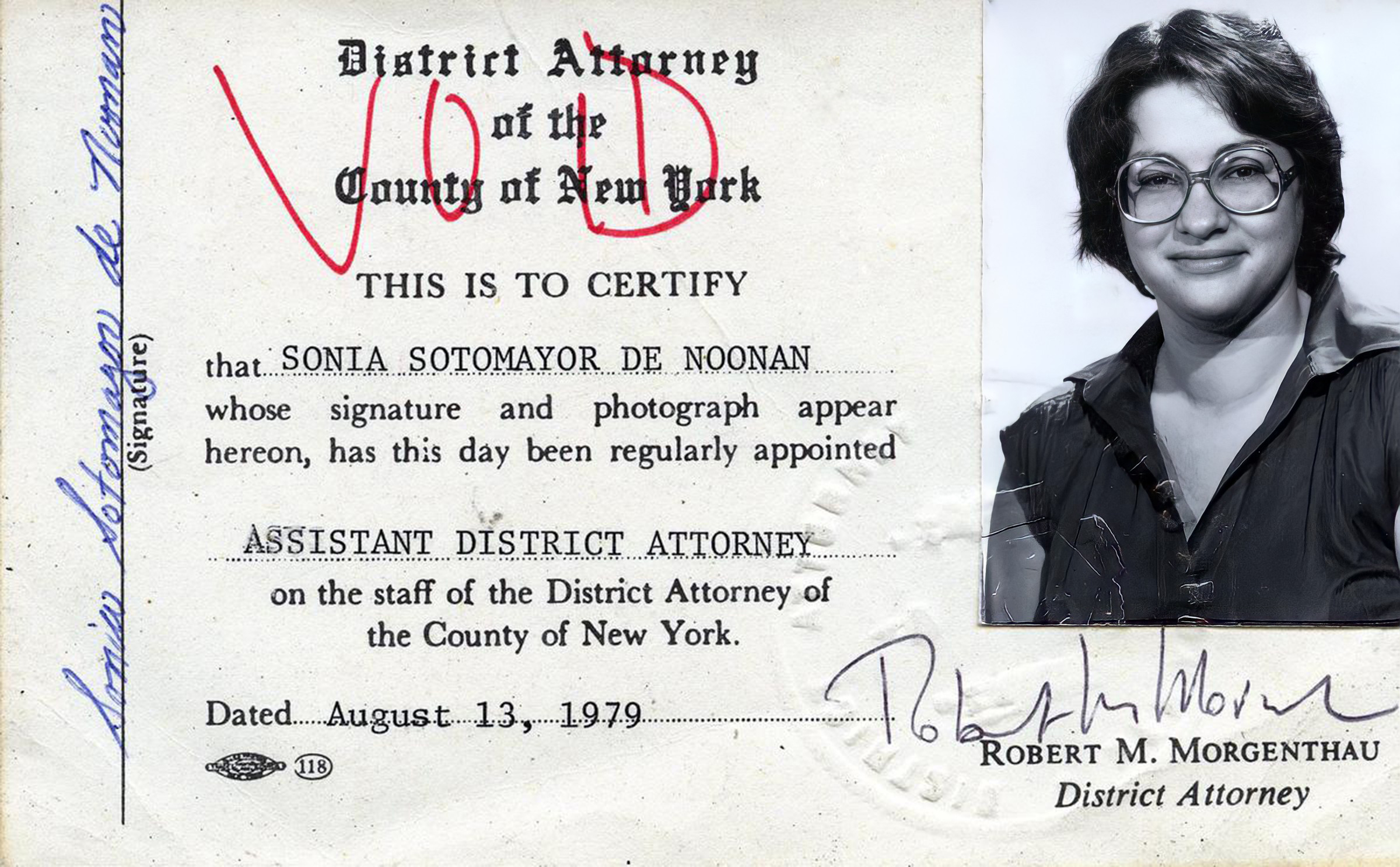

At Yale, Sotomayor was an editor of the Yale Law Journal and the managing editor of the law school’s journal of international law. At both Princeton and Yale Law School she spoke out for the rights of Latino students, and urged the universities to hire more Latino faculty members. When she graduated from Yale in 1979, she joined the office of New York’s District Attorney. As an assistant district attorney she spent nearly every work day of the next five years in the courtroom, prosecuting dozens of cases of murder, robbery, child abuse, drug trafficking, police misconduct and fraud.

Although her boss, longtime District Attorney Robert Morgenthau, praised her as a “fearless and effective prosecutor,” Sotomayor eventually found the endless procession of violence and crime demoralizing. The long hours in court and at the D.A.’s office had taken a toll on her marriage as well. In 1983, she and Kevin Noonan, also an attorney, ended their marriage on amicable terms. The following year, Sotomayor left the D.A.’s office to pursue private practice.

In 1984, she joined the law firm of Pavia & Harcourt as an associate. Her extensive courtroom experience had prepared her well to litigate civil cases; in her years with the firm she acquired special expertise in trademark and international trade cases. Many of her clients were foreign companies seeking to protect their trademarks from domestic counterfeiters. Sotomayor often accompanied the police in their raids on sellers of counterfeit merchandise, on one occasion pursuing a suspect on a motorcycle.

Within four years, Sotomayor had become a partner of the firm. During these years she also served on the boards of the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund, the State of New York Mortgage Agency and the New York City Campaign Finance Board.

One of her partners, David Botwinik, urged her to apply for an appointment as a federal judge. At 36, Sotomayor believed she was too young to be considered seriously for a judicial appointment. Botwinik kept pushing her and she finally applied. After an interview with New York’s U.S. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, he recommended her to President George H. W. Bush, who appointed her to serve as judge on the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York.

Over the next six years, she presided over roughly 450 cases. Among other matters, she was asked to rule on the dispute between Major League Baseball and the players’ union, a conflict that had caused the cancellation of the 1994 World Series. After a strike lasting 232 days, Sotomayor ruled in the players’ favor, ending the strike an hour before the 1995 season was about to begin. Her decision brought her national attention as “the judge who saved baseball.”

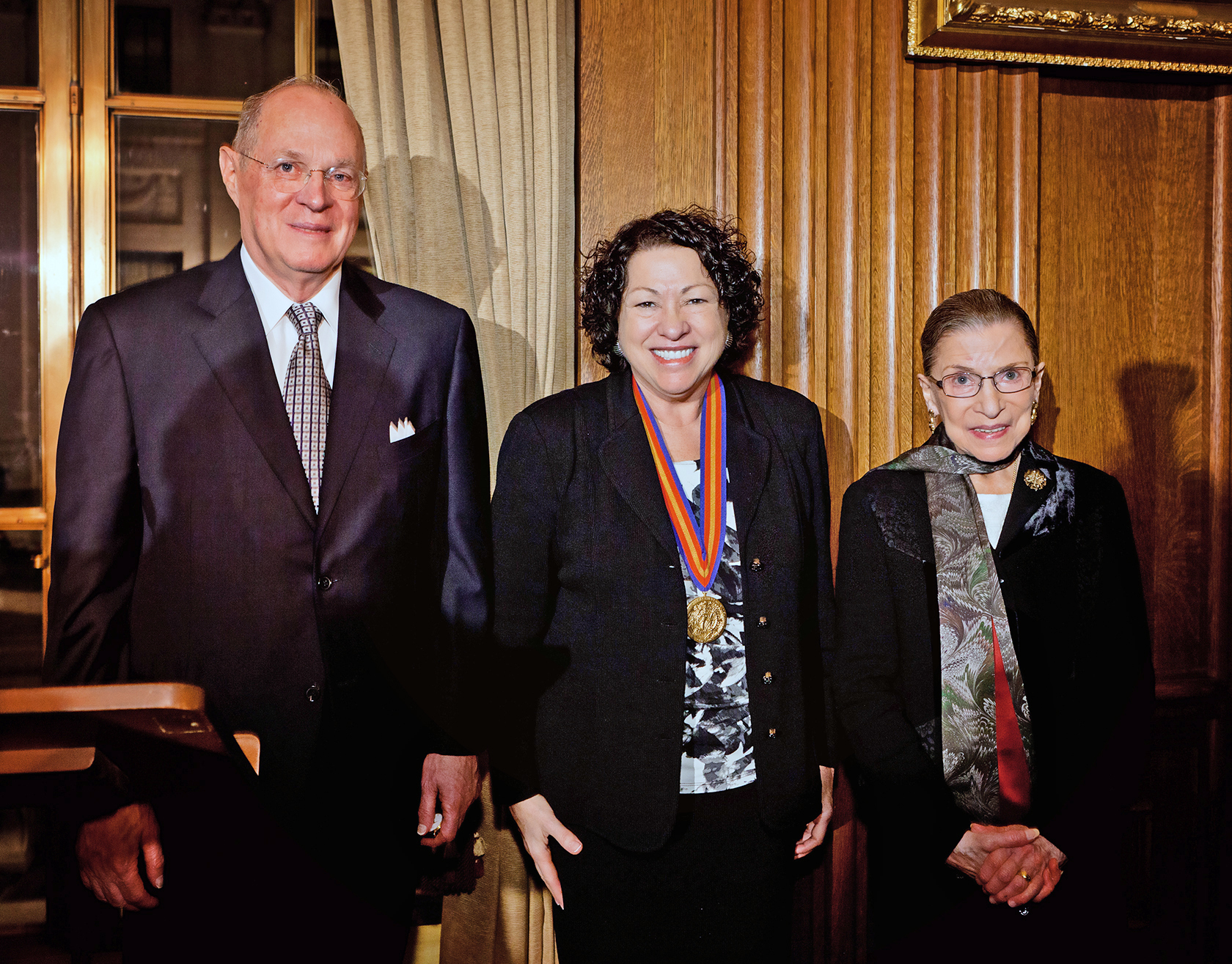

In 1997, President Bill Clinton nominated Sotomayor for the U.S Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. Her nomination was sharply debated in the United States Senate, but in 1998, a bipartisan majority confirmed her appointment. In her 11 years as an appeals court judge, Sotomayor heard more than 3,000 cases, and wrote nearly 400 opinions. While serving as a federal judge, she lectured in law at Columbia Law School and was an adjunct professor at New York University Law School.

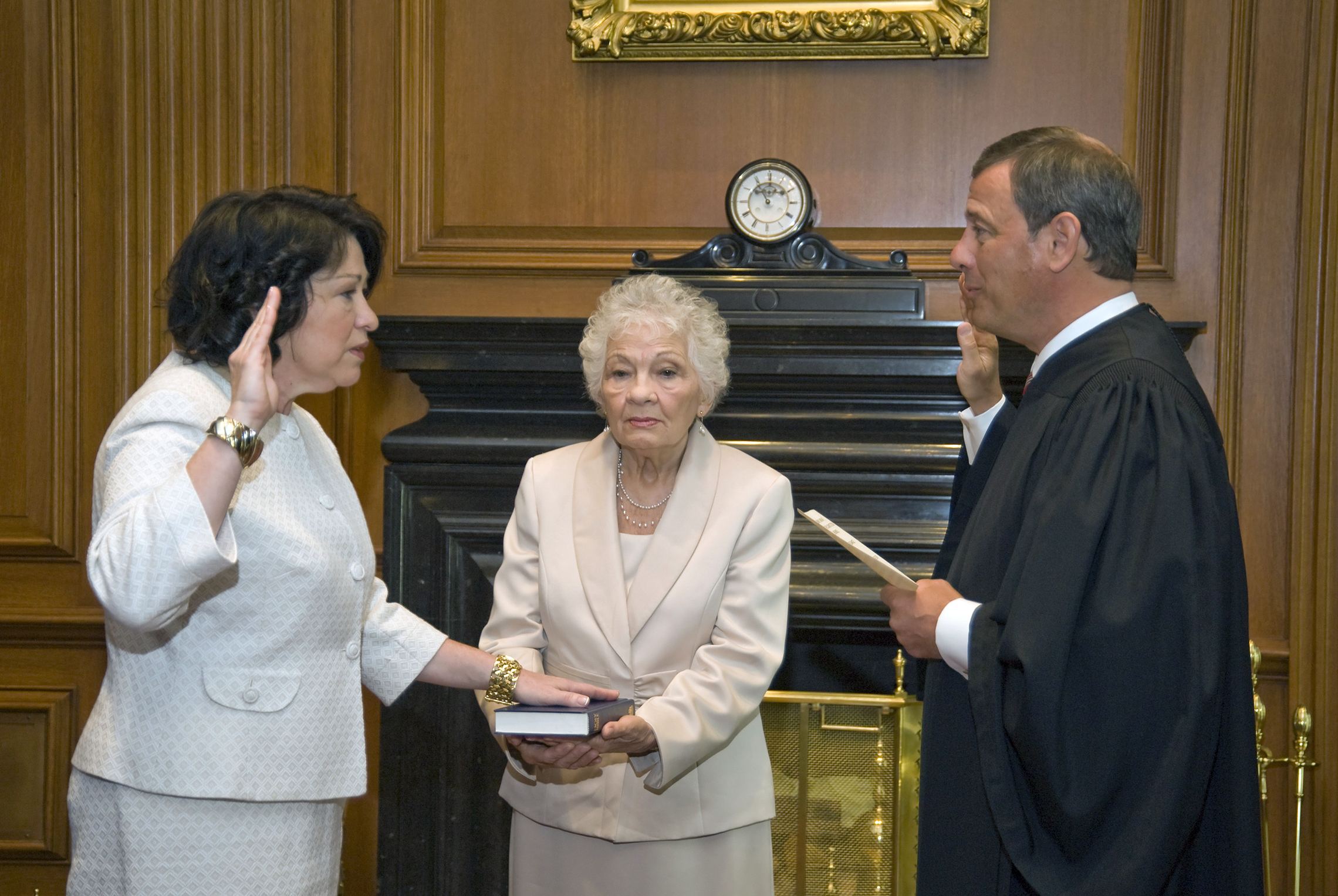

Shortly after his inauguration, President Barack Obama nominated her to the Supreme Court of the United States, to fill the vacancy left by the retirement of Justice David Souter. After a closely watched hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee, Sotomayor’s appointment was confirmed by the United States Senate by a vote of 68 to 31. She was the third woman, and the first person of Latin American descent to join the Court in its 220-year history.

Journalists who cover the Court typically group her with the “liberal bloc” of Justices, voting to allow gay marriage and uphold the Affordable Care Act, but she has pursued an independent course, placing the principles of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights ahead of any partisan consideration. As she had on the Court of Appeals, she continued to earn a reputation for tough and detailed questioning of attorneys presenting oral argument to the Court.

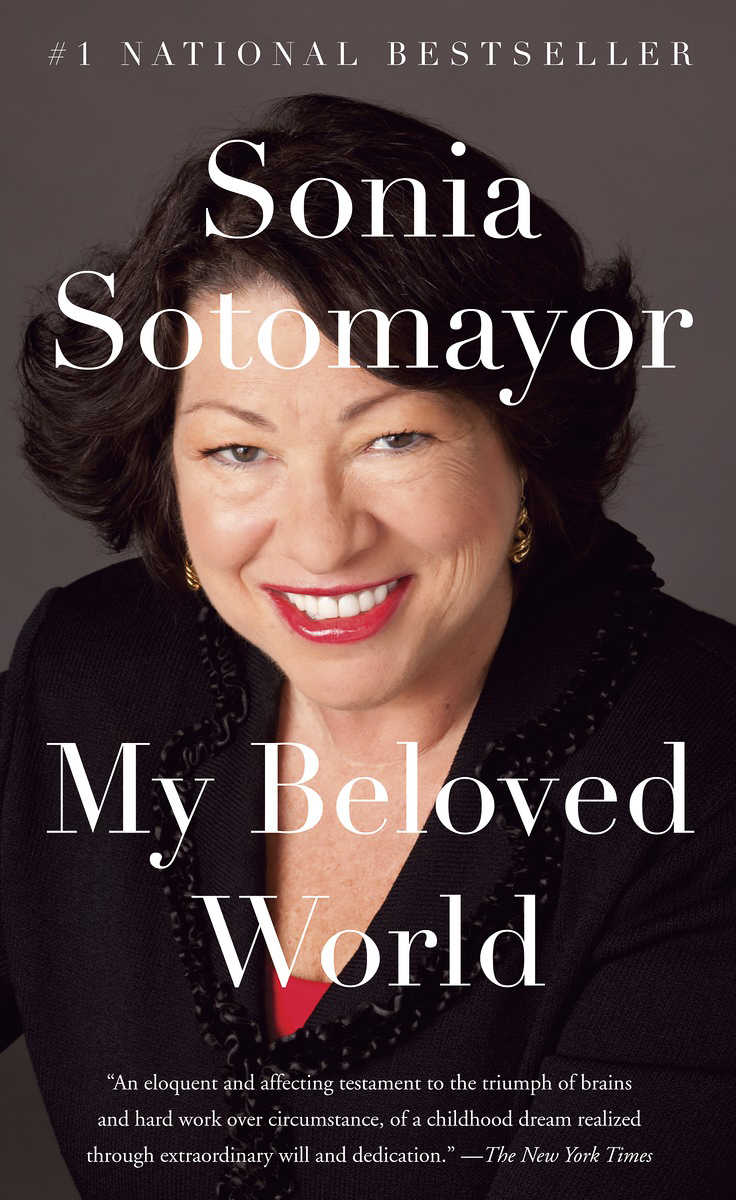

In 2013, her autobiography, My Beloved World, received excellent reviews and became a bestseller in both English and Spanish-language editions. The Bronxdale Homes where she lived as a child have been renamed in her honor, as has a multi-building public school complex in Los Angeles. She remains an inspiration to all young Americans who feel marginalized or excluded in American society. She continues to speak out in favor of diversity in higher education, as in a 2017 speech at the University of Michigan, where she reaffirmed her belief that “until we get equality in education, we won’t have an equal society.”

When President Obama nominated federal judge Sonia Sotomayor to the Supreme Court, many Americans welcomed the appointment as a historic milestone; she is the first Hispanic American to serve on the high court. Her colleagues on the federal bench praised her as “a role model of aspiration, discipline… and integrity.”

Born to Puerto Rican parents in New York City, Sonia Sotomayor grew up in a housing project in the Bronx. At age eight, she was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes, requiring daily insulin injections. Her father died the following year, leaving her mother to raise her and her brother alone. Young Sonia found solace in reading, and at age ten, decided that she would be an attorney. Sotomayor graduated summa cum laude from Princeton University and earned her law degree at Yale Law School.

As an assistant district attorney in New York City, she earned a reputation as a fearless prosecutor of violent crimes. She was still in her 30s when President George H. W. Bush appointed her to the federal bench for the Southern District of New York. Of the 450 cases she heard, one of her most famous rulings ended the major league baseball strike, just in time for opening day. Appointed to the U.S. Court of Appeals by President Clinton, she heard more than 3,000 cases and wrote roughly 380 opinions. Today, she is the only sitting Justice with experience as a trial judge, and brought more federal judicial experience to the Supreme Court than any appointee in 100 years.

You grew up in the Bronx. What was the neighborhood like when you were a child?

Sonia Sotomayor: For those kids who don’t know what it was, it was the worst neighborhood in the United States at the time and it was the South Bronx in New York City.

You’ve said you saw needles everywhere…

Sonia Sotomayor: Drug paraphernalia always in the staircase; in fact my mom wouldn’t let us go up or down the staircase because she was afraid of things that could be lying around.

And when you were seven, you learned you had diabetes.

Sonia Sotomayor: It was something that my mother the nurse tried to avoid understanding. And I finally fainted in church one Sunday morning, and the nuns made my mother send me to a doctor, where they immediately diagnosed the diabetes.

Sonia Sotomayor: When I was first diagnosed, because I left the hospital taking insulin, one shot a day back then. Today it’s many, many more shots than that, but back then it was one shot a day, and I would sterilize the needle in a pan. I had to get up on a chair to be able to reach the top of the stove and light it. It wasn’t an automatic stove like today. I wasn’t in the dinosaur ages, but this was the 1950s and things have changed a lot since then. At any rate, I had to light the stove, put the pot of water with the needles in it, wait until it boiled, it seemed to take forever. And then remove the water and let the works, the insulin works, the injection works cool down before I started to draw the insulin and give myself a shot. It was a process.

This was all in pursuit of having your parents not fight over who was going to give you your shot.

Sonia Sotomayor: Absolutely.

And getting to spend the weekend with your grandmother, your Abuelita, because she wouldn’t give you a shot.

Sonia Sotomayor: My grandmother, she adored me. I willingly admit, and so does every other cousin I have, that I was her favorite granddaughter. I take that with a great deal of pride and absolutely no sense of humility about it. I was her favorite. But I also knew she didn’t have the heart to give me a needle. It would have been emotionally too tough for her. And what would have ended up happening is I wouldn’t have been able to stay over with her because I needed the shot every morning. And so it immediately became clear to me as soon I left the hospital that if I didn’t learn how to do this right away I would miss out on that very precious time with my grandmother, and it was something I simply wouldn’t give up.

Your mother was gone a lot, and you had a chilly relationship with your dad, who — you’ve said very candidly — was an alcoholic.

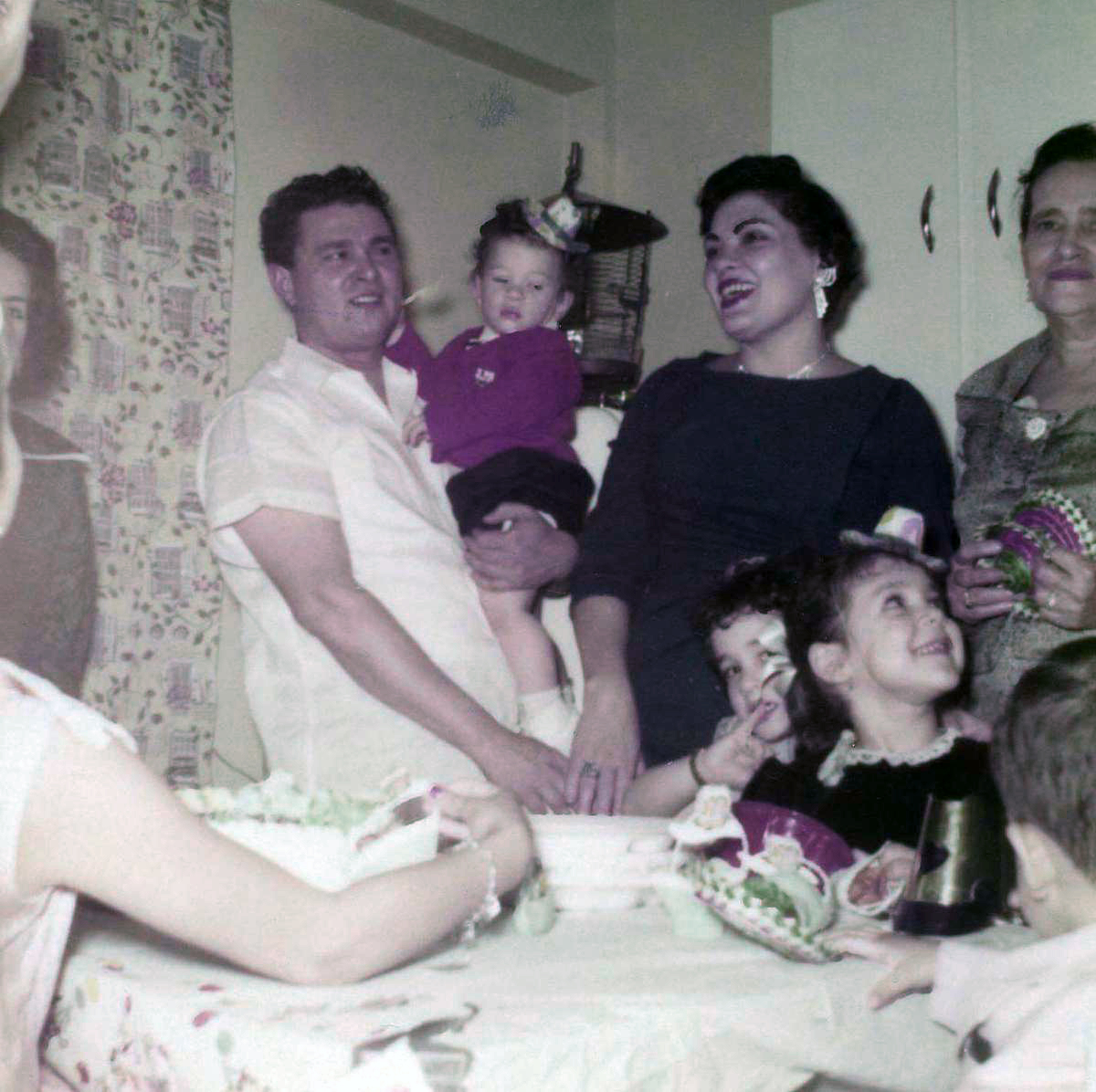

Sonia Sotomayor: The strange part when you talk about someone who you know loves you… my father adored my brother and I. And in fact in writing my book, the publisher asked me for photographs, and I went back to a childhood photograph that has hung in my mother’s house since I was about three and my brother was one. And I took the photograph out of its frame for the first time, and in the back was a handwritten message by my father, explaining that the photograph had been taken at my brother’s first birthday. And my brother was just… and my father was describing his tesoro, his treasure, his little boy. And then talking about me, and talking about how I lit up his life. And he also spoke about his love for my mother in this, it’s about two, three paragraphs short. And I realized that my judgement that he adored us was true. But his love for us couldn’t stop him from drinking himself to death. Addictions are an affliction on people who can’t find what they need within themselves to put them aside and to seek help to put it aside. Most addictions require intervention, not just by you on your own strength of character, but the intervention of family and friends. Back then I don’t know that my mother knew what she could do to save my father. Thankfully today, there are many, many more programs that people are familiar with.

So you were nine when your father died. We gather you were unprepared for your mother’s grief because when he was alive they were fighting all the time. In your book you describe this moment when you finally broke, because your mother was sort of disappearing on you.

Sonia Sotomayor: Mom was depressed, I learned later. She’s very technical now; she says, “I wasn’t depressed, I was sad. I was grieving.” And she explains that she knew that his drinking was causing him physical harm. He had had one heart attack five years before he died. So a second was going to be very likely if he continued drinking, which is what the doctor told him.

In fact I’m not sure I relay in my book anymore that the doctor who took care of my father learned that my mother had stopped paying my father’s life insurance. I don’t know how he learned that but in some passing conversation with my mother. And insisted that she do so. Insisted so much that she finally felt compelled to pick up the policy again and continue paying it.

It was quite helpful, at least it permitted us to bury him. It wasn’t a huge policy. It was a couple of thousand dollars but in those times it was a lot of money. It’s what helped us move from the projects to Co-op City, which was out of the projects to a private apartment complex in upper, in the upper part of the Bronx.

But my mother says that she just… you can understand the inevitable, but coming to the reality was a different thing for her. Realizing that he was now dead and how special a time they had had in the beginning of their romance made her grieve deeply. And I called it depression in an unsophisticated way. I think she’s right, she was probably just grieving. But we would come home from school in the afternoon, she would have dinner prepared for us and she would go back into her room and cry all night. And you’re right, about a year later, I let it go on, I let it go on, I’m sounding like I’m some god or something. But my brother and I had been quietly sitting in the house watching television or reading books — books was my favorite pastime. And I’d just had enough one day. She locked herself back in the room, and I started to cry, and I went up to the door and started banging on it. And I was screaming at her, “You’ve got to stop this. You’re dying on us and you’re going to leave us alone. We don’t deserve to be left alone. Please, please stop.” And I finally just ran away from the door when she didn’t open it. And I didn’t know at that moment what my impact was. I actually fell asleep that night crying. But the next morning, my mother woke us up, and she said she doesn’t remember this dress, but it was a black with white polka dot dress. And her hair was finally properly combed. She had for the first time in a year some makeup on, and I knew my mom was back. And that may have been one of the happiest moments of my life.

What about school? We hear you were sort of a middling student until the nuns started giving out gold stars. How did that come about?

Sonia Sotomayor: I wanted my gold stars. It wasn’t actually a nun, it was a teacher in fifth grade who would reward students who had performed well on their assignments with gold stars. And I wanted gold stars. And I realized that to get them I had to figure out how to study. And I did something that has helped me my entire life, and it’s something I still do, which is when I don’t know how to do something now I start reading about it. Back then I would ask people for help. And I have found that if you go to people and ask them for help that it feels like a compliment to them. Because everybody likes feeling good and likes doing something for other people, especially when what they’re going to do is easy for them.

And so I went to the smartest student in the class, and I looked at her, she’s still a friend today. This is Donna. And I said, “Donna, please tell me how you study. I don’t know how to study.” And she said to me, “You don’t know how to study?” She found the question odd but sat down and told me how she studied. How she would read the materials, she would underline the important parts of it. She would make sure at the end of every chapter that she understood what she had read before she moved on to the other chapter. How before a test she would read all of the underlined sections to remind her of what she had studied. And so I thought to myself, “Well that seems like something I can do.” And that’s what I started to do, and from a middling student I went to the top of my class, pretty quickly. Donna to this day says that was maybe the worst mistake in her life, because I started doing better than she did.

So you graduated at the top of your high school class, and then your boyfriend — I think it was your boyfriend — suggests that you should apply to the Ivies, and you had no idea what he was talking about.

Sonia Sotomayor: Ken had gotten into Princeton because his math teacher at our high school had suggested to him that he should apply to the Ivy Leagues. He also didn’t know what they were but his teacher told him, he went, and he calls me up one day and says, “Sonia, you have to apply to an Ivy League college.” And my next question was, “What’s that?” He described it as the best colleges in the United States. That was his simple answer. My second question was, “How do I get in?” And he said, “You apply.” Which sounds so simplistic, doesn’t it? And almost unbelievable. But I think kids have to understand that we’re talking about an age where there wasn’t the Internet. Where really, television programs weren’t as concentrated on education as they are today. A lot of that started to grow up with me but weren’t a part of the life I was in at the time. At any rate, he says to me, “You apply. Our guidance counselors will give you the applications.” I said, “How much will it cost me?” And he retorted by saying, “Nothing, because you’re as poor as I am. You’ll get a scholarship.” I said, “Alright, how much are the applications, do I have to pay for that?” He said, “Same thing, they’re going to waive them, don’t worry. Just apply.” So I asked him which ones to apply to. He told me, I applied to them, and lo and behold I got in. But it was not with an understanding of what I had accomplished. That came after I got in. As I was telling people about where I was going to college, and I could see both surprise in their faces and a sense of, I think the word is “admiration,” in their eyes. And from there I began to understand that getting into a place like Princeton wasn’t a norm. And it certainly wasn’t expected of a child like me. But it was something that would be important to me.

When you were at Princeton you ended up graduating with honors, you won all kinds of awards. You won the Pyne Prize.

Sonia Sotomayor: I didn’t know what that was either.

But the first two years were a real slog. Can you tell us what that was like?

Sonia Sotomayor: I’ve learned very early in my life that if you compete against other people you’re going to find yourself wanting in some way. Especially because none of us are perfect, we’re human beings. We do some things well, we do other things not so well. Other people do some things well, and other things not well. But if you put yourself in competition with others you’re going to find yourself disappointed. And I figured out a sure-fire way to avoid that disappointment, which was to figure out what I needed to do, each day, to improve myself. To set my goals not against the accomplishments of other people but to set my goals against what I wanted to accomplish, how I wanted to improve.

So I spent my first two years at Princeton, again learning how to learn. How to write papers because I went in from a fairly decent high school but where writing wasn’t its emphasis. Multiple choice was and I was great at multiple choice. Short answers, I can do fabulously. Longer essays, I had very little practice with when I went to high… when I went to college. And so I had to figure out how to start writing persuasive essays. I also had to figure out how to finally master writing English because I had taken on so many of the grammatical, or grammatically-induced errors of translating from Spanish to English. So what I did was I went out and bought grammar books from first to twelfth grade, I reread them. I worked with a professor at college, who, every paper I wrote, he would circle my errors and explain what I had done.

Was this after you got a C on your first paper?

Sonia Sotomayor: I got a C on my first paper, and I knew, this is when I knew I had to learn how to write. But my professor, Peter Winn, who is still teaching now, I remember the first words he circled, which were “dictatorship of authority.” Oh no, so “authority of dictatorship,” “authority of dictatorship.” And Professor Winn looked at me, and he said, “There are a lot of nouns in Spanish where an adjective is added with the preposition ‘of.'”

So you don’t, we don’t say in Spanish, “shirt, cotton.” In Spanish we say, “shirt of cotton,” not “cotton shirt.” So he said, “This should be ‘dictatorial authority.’ It’s an adjective, you put it before the noun.” And I went, “Oh.” He said, “Now go back and find all the places in the paper where you did that and fix it.” And so that’s what I do, and the next paper, with that lesson in mind, I would write out my essay.

I would go back and correct all of those errors. We did that paper after paper, error after error, and by the time I finished Princeton, after a lot of papers, I got an A from the reader on my senior thesis, who said that it was the best written thesis he had read that semester. That was a compliment that I thought I had earned.

But what I understood was that I had to work to get it. Nothing comes naturally. I had a roommate in college who is still a friend who would write her papers the night before they were due. I couldn’t do that. Because I have to read everything I write and edit it. So I’m not a natural writer. She’s more a natural writer than I am. But I can do what I need to do to give myself enough time to write papers, edit them, before I turn them in. And that’s what I still do.

Is that the same roommate who said you were like Alice in Wonderland?

Sonia Sotomayor: I was talking to her one day about how alien a world Princeton was to me, having come from a very urban environment to a sort of, not rural, but suburban existence that Princeton was. Being with kids who had grown up in private schools, who spent vacations in places I had only read about, and that no one in my family ever imagined they could visit. I was trying to describe to her how alien I was in this world. And she looked at me and said, “You’re like Alice in Wonderland,” and I looked at her and said, “Who’s Alice in Wonderland?” And she said, “You haven’t read the book?” And I said, “No.” So she looked at me and said, “Hmm. I have it at home. When I go back over the holidays I’ll bring it back to you.” Which she did. But I realized, I asked her when she had read it, and she said in grammar school. I then looked at her and said, “What other books did you read in grammar school?” because in my Spanish home, Alice in Wonderland wasn’t a part of what we read. My mother bought the Reader’s Digest so that we could have some understanding of popular literature, but she didn’t know how to guide me in my classical reading. So Mary gave me a very long list of books to pick up and read, and one of my summers in college I read all those books. And I finally did get to read Alice in Wonderland, and I felt just like her.